Abstract

To reduce the health security risk and impact of outbreaks around the world, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and its partners are building capabilities to prevent, detect, and contain outbreaks in 49 global health security priority countries. We examine the extent of economic vulnerability to the US export economy posed by trade disruptions in these 49 countries. Using 2015 US Department of Commerce data, we assessed the value of US exports and the number of US jobs supported by those exports. US exports to the 49 countries exceeded $308 billion and supported more than 1.6 million jobs across all US states in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, oil and gas, services, and other sectors. These exports represented 13.7% of all US export revenue worldwide and 14.3% of all US jobs supported by all US exports. The economic linkages between the United States and these global health security priority countries illustrate the importance of ensuring that countries have the public health capacities needed to control outbreaks at their source before they become pandemics.

Keywords: : Global health security, US exports, US jobs, US economy, Pandemics

The authors examine the extent of economic vulnerability to the US export economy posed by trade disruptions in the 49 global health security priority countries. Using 2015 US Department of Commerce data, they assess the value of US exports and the number of US jobs supported by those exports.

Many challenges exist worldwide that increase the risk of outbreaks and impede prevention, rapid response, and containment of health security threats. These challenges include increased risk of infectious pathogens “spilling over” from animal reservoirs to human hosts, development of antimicrobial resistance, spread of infectious diseases by global migration, acts of bioterrorism, and weak public health infrastructures.1,2 In addition to these increased risks, the efficiency of the global transportation network means that an infectious pathogen can be carried from a remote village to major cities across 6 continents within 36 hours and could cause a large-scale outbreak or pandemic.3 The world's interconnectivity was illustrated during the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic, when cases of Ebola occurred in 10 countries, including 4 cases in the United States.4 Outbreaks, even without crossing borders, can disrupt trade flows by destabilizing economies that serve as export markets. For example, Lee and McKibbin estimated the global economic impact of the 2002-03 SARS epidemic was almost US$40 billion.5 Bloom and colleagues estimated that the economic consequences for Asia for an avian influenza outbreak that lasted a full year would cause a reduction of approximately US$283 billion in demand and US$14 billion in supply worldwide.6

To prevent large-scale outbreaks, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working with partners in 49 global health security priority countries to improve the capabilities of public health infectious disease laboratories, workforce, and surveillance and response systems.7,8 These activities enhance global health security by building national capabilities to prevent, rapidly detect, and control infectious disease outbreaks at their sources, before they cross borders and cause widespread health and economic disruption.2,7-9 To better characterize US economic linkages to the 49 health security priority countries, we assessed the value of US goods and services exported to these priority countries and the number of US jobs supporting those exports. This assessment quantifies the extent of economic vulnerability to the US export economy posed by trade disruptions in these 49 countries.

Methods

We defined global health security priority countries (priority countries) as meeting 1 or both of the following inclusion criteria: (1) countries designated by the US government as Phase I or Phase II countries under the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA),7,8 and (2) countries hosting a CDC Global Disease Detection (GDD) center10,11 (see supplementary material for full list of countries: http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/hs.2017.0051/suppl_file/Supp_Data.pdf). These criteria were used to ensure inclusion of key countries that receive CDC assistance for global health security work, ranging from minimal technical assistance for GHSA Phase II countries, to a 5-year commitment to provide both technical assistance and some funding to GHSA Phase I countries, to longer timeframe technical partnerships and funding for countries designated as GDD countries.

We assessed the value of US exports and jobs supported by such exports to the priority countries using publicly available data sets.12-15 Data that record the value of material goods exported from individual US states are accessible through the International Trade Administration's (ITA) Trade Policy Information System (TPIS) and were available for all 49 priority countries.15 The US Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) data depict the value of services exported to countries with a free trade agreement with the United States (see Supplementary Material: Appendix for definition of service exports at http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/hs.2017.0051). Data for service-related exports exist for only 10 of the priority countries. Service-related export data for those 10 countries were included in our analysis. The value of exports refers to the summation of both goods and services. We also calculated the proportion of worldwide exports that went to the 49 priority countries and the corresponding proportion of all export-supporting US jobs related to exports to priority countries. The numbers of US jobs supported by material goods and/or services exported were generated from analyses of US Department of Commerce data.14-17

Because China is the largest destination country of all priority countries, we analyzed the aggregated export values and US jobs supported by these exports including and excluding China.15 For all analyses, we used 2015 data, which were the most recent available. Additional details regarding the data and our analytical assumptions are in the Appendix (see Supplementary Material: Appendix).

Results

In 2015, the estimated total value of US material goods and/or services exported to all countries worldwide was approximately $2.3 trillion (Table 1). The total value of US exports to the 49 priority countries was more than $308 billion, including over $222.5 billion in material goods and over $85.9 billion in services exported. This represented 13.7% of all US exported material goods worldwide (Table 1). For the 49 priority countries, the largest export sector was manufactured goods and services, totaling over $178.9 billion and constituting 80.4% of the total value of exported material goods to priority countries (Table 1). The second largest material goods export sector was agricultural goods, followed by other exports and mining, oil, and gas (Table 1). Sector-specific proportions of exports varied by state (Appendix Table 1).

Table 1.

Value of 2015 US Exports, by Sectors, to Global Health Security Priority Countries Compared to Total US Exports Worldwidea

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting (USD) | Mining, Quarrying, and Oil/Gas Extraction (USD) | Manufactured Goods (USD) | Other Exports (USD) | Total Value for Exported Material Goods (USD)b | Total Value of Services Exported (USD)c | Total Value of Exported Material Goods and/or Services (USD) | Number of US Jobs Supported by Material Goods and/or Services Exportedd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total for All 49 Global Health Security Priority Countriesa | $25,520,977,109 | $3,472,996,358 | $178,933,050,381 | $14,645,630,194 | $222,572,654,042 | $85,928,000,000 | $308,500,654,042 | 1,644,200 |

| Total US Exports Worldwide | $72,996,154,511 | $34,829,244,566 | $1,316,213,888,251 | $78,396,752,816 | $1,502,436,040,144 | $750,860,000,000 | $2,253,296,040,144 | 11,515,500 |

| Percentage of 49 Global Health Security Priority Countries Relative to US Exports Worldwide | 35.0% | 10.0% | 13.6% | 18.7% | 14.8% | 11.4% | 13.7% | 14.3% |

USD = US dollars (2015 dollars)

See Appendix for definition and list of countries included in the 49 health security priority countries.

Included estimated summation of the following first for columns (categories): agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting + mining, quarrying, and oil/gas extraction + manufactured goods + other exports. Per the North America Industrial Classification Standard (NAICS), other exports are defined as waste, used merchandise and special classification. Data for the first 4 categories were downloaded from the International Trade Administration's Trade Policy Information System (TPIS) website by selecting the health security priority countries.13

Service data only available for countries where US has trade agreements or presence (n = 10). Service data can be found on the US Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) website.12–17 Service data on the BEA website is rounded to the nearest million.

China was the largest single importer of US exports, importing more than $164.5 billion of material goods and/or services (Appendix Table 2). The next 3 largest importers among the priority countries were all in South Asia and Southeast Asia: India, Malaysia, and Thailand (imports of $39.6 billion, $15.1 billion, and $13.9 billion, respectively). South Africa was the largest importer in sub-Saharan Africa, with over $8.6 billion in US imports. This was almost double the $4.8 billion imported by Egypt. Peru was the largest importer among the priority countries, importing over $12.6 billion worth of goods and services from the United States (Appendix Table 2).

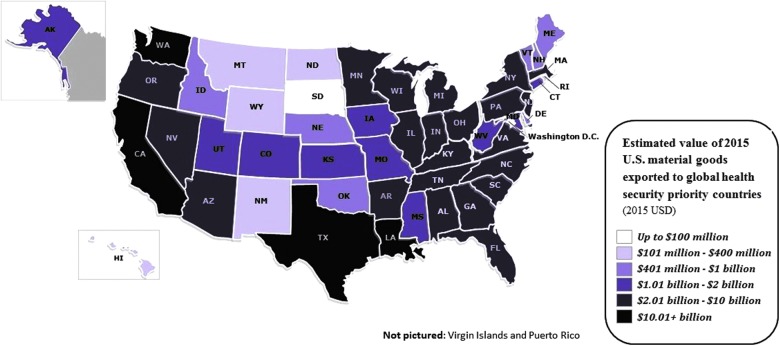

The total value of material goods exported from specific US states to the 49 priority countries varied, with Washington ($28.8 billion), California ($27.2 billion), and Texas ($26.1 billion) having the largest export values (Figure 1, Appendix Table 1). California, Texas, and Washington also were the largest exporters of manufactured goods to the priority countries, with each exporting more than $21.5 billion (Appendix Table 1). For agricultural exports, Louisiana had the largest export value at nearly $6.5 billion. After Louisiana, states with the next largest agriculture export values were Washington, California, Texas, Illinois, and Ohio.

Figure 1.

Value of US Material Goods Exported to Global Health Security Priority Countries (n = 49) by State in 2015. (see Supplementary Material, Tables 1 and 2, at: http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/hs.2017.0051)

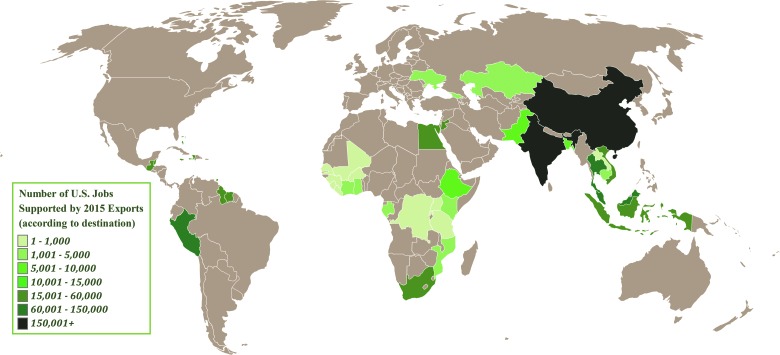

Overall, in 2015, US exports of material goods and services to 49 priority countries supported 1,644,200 US jobs, or 14.3% of the US total of over 11.5 million export-related jobs (Table 1 and Appendix Table 2). The largest numbers of US export-related jobs were linked to exports to priority countries in Asia (Figure 2, Appendix Table 2). Numbers of US jobs supported by these exports varied greatly by volume of exports per destination country. Exports to Montserrat, for example, were quite limited, and only 30 US export-related jobs could be attributed to that country (Appendix Table 2).

Figure 2.

Number of US Jobs Supported by US Exports to Global Health Security Priority Countries, According to Destination in 2015. (see Supplementary Material, Tables 1 and 2, at: http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/hs.2017.0051)

Exports to China constituted 53.3% of total exports to the priority countries. Excluding China, the overall value of exports to the remaining 48 countries totaled approximately $144 billion, representing 6.4% of the total value of all US exports globally. Exports to these 48 priority countries supported 733,560 US jobs, which is 6.4% of all jobs supported by exports.

Discussion

In 2015, the total value of US exports to 49 global health security priority countries exceeded $308 billion. Those exports supported more than 1.6 million American jobs across all US states and involved numerous sectors, including manufacturing, agriculture, mining, oil and gas, and service industries. This substantial economic export activity to the 49 priority countries suggests that economic disruptions in those 49 countries, including those associated with infectious disease outbreaks, could result in reduced demand for US exports. The US export economy is vulnerable to economic disruptions, and such disruptions could negatively affect US export-supporting jobs.

Not unexpectedly, we found a strong link between the US economy and China, and China accounted for over 50% of the US exports to the 49 priority countries. However, our findings that all US states have jobs and exports connected to global health security priority countries remained consistent even when China was removed from the analysis.

Our sector-specific findings showed that manufactured goods comprised a large majority of exports to the 49 priority countries. Given that 2015 industry data showed that the manufacturing sector supported a higher proportion of jobs than any other sector,18 it is likely that manufacturing-related exports to these priority countries also supported the majority of export-related jobs.

Our analysis has several limitations, at least 2 of which are due to the nature of available data. We lacked service-export data for 39 of the 49 priority countries, which means we likely underestimated the value of exports and associated jobs for those countries. Also, it was not possible to determine the original US state where goods were actually produced, as available data only report the US state from where the final goods were exported.12,15 Consequently, we were not able to calculate state-specific numbers of export-supported jobs. Future analyses, including assessments of pandemic-specific impacts and state- and sector-specific impacts on exports and jobs, could further characterize the linkages between US exports and jobs and global health security.

In addition, our estimates included only the dollar value of the exports themselves. We have not included estimates of the additional impact on the US economy due to exports. It is difficult to calculate the additional export-related impacts on the US gross domestic product, and such an analysis is beyond the scope of this article. However, prior work suggests that exports are directly correlated with economic growth.19 Finally, the economic vulnerability of the United States to infectious disease outbreaks is likely to extend well beyond just exports and export-supporting jobs and include broader, and potentially larger, impacts stemming from the fear of contagion on travel, tourism, and imports, especially if cases occur in the United States, as they did in the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak.4

Demonstrating in detail the extent to which CDC's efforts and partnerships have resulted in improved capabilities to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks in the priority countries is also beyond the scope of this analysis, but, in sum, clear progress has been made in many countries.7,8 Nevertheless, critical gaps remain, and many priority countries are working to improve on initial low scores related to pandemic preparedness, as measured by the World Health Organization's use of the Joint External Evaluation (JEE) tool.20,21 Countries continue to improve their public health capabilities to rapidly prevent, detect, and control infectious disease outbreaks. The economic links between the US export economy and global health security suggest that continued capacity-building in other countries may be important to protect US exports, export-related jobs, and the broader economy from outbreak-related disruptions. According to the Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework, investments in building such capacities could be cost-saving. The commission estimated that pandemics are likely to cost over $6 trillion in the next century, with an annualized expected loss of more than $60 billion for potential pandemics. However, the commission recommended that a $4.5 billion per year investment in building global capacities would avert the high cost of pandemics.1

Building on the present assessment of US export data, a related recent analysis of hypothetical outbreak scenarios in Southeast Asia suggested a substantial impact of outbreak disruptions on US exports and export-supporting jobs.22 Combined with the present analysis, these analyses illustrate the potential economic disruption to the US export economy and our export-supporting jobs should a large-scale outbreak occur in any of the global health security priority countries.22 These findings may be useful to inform decisions about the value of public health programs, investments, and policies aimed at building public health capacity worldwide. When all countries are able to rapidly prevent, detect, and control outbreaks at their source, the risk of large outbreaks and pandemics can be reduced and global health security enhanced.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Chris Rasmussen, PhD, from the US Department of Commerce, Washington, DC, for his comments and feedback on this project. We thank Deliana Kostova, PhD, for assistance in data analysis; Diane Brodalski for figure preparation; and Frederick J. Angulo, DVM, PhD, and David L. Bull, PhD, for providing feedback on the paper; all of whom are with the Division of Global Health Protection, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. All authors contributed to this work as part of their regular assigned duties as US federal government employees. No author has financial ties or disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the topic, material, and conclusions presented in this article. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future. The Neglected Dimension of Global Security: A Framework to Counter Infectious Disease Crises. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Neglected-Dimension-of-Global-Security.pdf Accessed November7, 2017 [PubMed]

- 2.Frieden TR, Tappero JW, Dowell SF, Hien NT, Guillaume FD, Aceng JR. Safer countries through global health security. Lancet 2014;383:764-766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonas OB. Pandemic Risk. World Development Report 2014. Washington, DC: Open Knowledge Repository, World Bank Group; 2013. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16343 Accessed November7, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Ebola situation report. 30 March 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204714/1/ebolasitrep_30mar2016_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 Accessed November7, 2017

- 5.Lee JW, McKibbin WJ. Estimating the global economic costs of SARS. In: Knobler S, Mahmoud A, Lemon S, Mack A, Sivitz L, Oberholtzer K, eds. Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom E, de Wit V, Carangal-San Jose MJ. Potential Economic Impact of an Asian Flu Pandemic on Asia. Policy Brief #42. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, Economic and Research Department; 2005. https://think-asia.org/bitstream/handle/11540/2165/pb042.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed November7, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tappero JW, Cassell CH, Bunnell RE, et al. . US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and its partners' contributions to global health security. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(Suppl). https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/13/17-0946_article Accessed November7, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Fitzmaurice AG, Mahar M, Moriarty LF, et al. . Contributions of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in implementing the Global Health Security Agenda in 17 partner countries. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(Suppl). https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Wolicki SB, Nuzzo JB, Blazes DL, Pitts DL, Isklander JK, Tappero JW. Public health surveillance: at the core of the Global Health Security Agenda. Health Secur 2016;14:185-188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao CY, Goruoka GW, Henao OL, Clarke KR, Salyer SJ, Montgomery JM. Global disease detection—achievements in applied public health research, capacity building, and public health diplomacy, 2001-2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(Suppl). https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Disease Detection Program: where we work. CDC website. Updated October 16, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/gdd/where-we-work.html Accessed November7, 2017

- 12.US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). U.S. International Economic Accounts: Concepts and Methods. https://www.bea.gov/international/pdf/concepts-methods/ONE%20PDF%20-%20IEA%20Concepts%20Methods.pdf Accessed November7, 2017

- 13.US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). BEA international trade and investment country facts. https://www.bea.gov/international/factsheet/ Accessed November7, 2017

- 14.US Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (ITA). Jobs supported by export destination. Excel data. http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/documents/webcontent/tg_ian_005513.xlsx Accessed March9, 2017

- 15.US Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (ITA). Trade Policy Information System (TPIS database). http://tpis1.trade.gov/cgi-bin/wtpis/prod/tpis.cgi Accessed November7, 2017

- 16.Rasmussen C. Jobs supported by exports 2015: an update. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (ITA); 2016. http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/documents/webcontent/tg_ian_005500.pdf Accessed November7, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasmussen C, Xu S. Jobs supported by export destination 2015. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (ITA); 2016. http://trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/documents/webcontent/tg_ian_005508.pdf Accessed November7, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall J, Rasmussen C. Jobs supported by state exports 2015. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (ITA); 2016. http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/documents/webcontent/tg_ian_005503.pdf Accessed November7, 2017

- 19.Lewer JJ, Van den Berg H. How large is international trade's effect on economic growth? J Econ Surv 2003;17:363-396 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joint External Evaluation (JEE) Alliance. Joint External Evaluation. https://www.jeealliance.org/global-health-security-and-ihr-implementation/joint-external-evaluation-jee/ Accessed November7, 2017

- 21.Bell E, Tappero JW, Ijaz K, et al. . Joint External Evaluation—development and scale-up of global multisectoral health capacity evaluation process. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(Suppl). https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bambery Z, Cassell CH, Bunnell RE, et al. . Impact of hypothetical infectious disease outbreak on US exports and export-based jobs. Health Secur. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.