Abstract

Objective

This research aims to determine the long-term impact of the Bloor Street Viaduct suicide barrier on rates of suicide in Toronto and whether media reporting had any impact on suicide rates.

Design

Natural experiment.

Setting

City of Toronto, Canada; records at the chief coroner’s office of Ontario 1993–2003 (11 years before the barrier) and 2004–2014 (11 years after the barrier).

Participants

5403 people who died by suicide in the city of Toronto.

Main outcome measure

Changes in yearly rates of suicide by jumping at Bloor Street Viaduct, other bridges including nearest comparison bridge and walking distance bridges, and buildings, and by other means.

Results

Suicide rates at the Bloor Street Viaduct declined from 9.0 deaths/year before the barrier to 0.1 deaths/year after the barrier (incidence rate ratio (IRR) 0.005, 95% CI 0.0005 to 0.19, p=0.002). Suicide deaths from bridges in Toronto also declined significantly (IRR 0.53, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.71, p<0.0001). Media reports about suicide at the Bloor Street Viaduct were associated with an increase in suicide-by-jumping from bridges the following year.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that, over the long term, suicide-by-jumping declined in Toronto after the barrier with no associated increase in suicide by other means. That is, the barrier appears to have had its intended impact at preventing suicide despite a short-term rise in deaths at other bridges that was at least partially influenced by a media effect. Research examining barriers at other locations should interpret short-term results with caution.

Keywords: Suicide & self-harm, means restriction, media, bridge barrier

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study strengths include that this natural experiment examines long-term data for a means restriction strategy introduced at what was formerly one of the world’s most significant suicide ‘hotspots’.

Media coverage of the Bloor Street Viaduct as a ‘hotspot’ was variable in amount but spanned all 18 years of the study allowing for the examination of suicide contagion over a longer timespan than is typically possible.

Study limitations are the potential for an ecological fallacy, that only print media were examined, that suicide deaths by jumping from bridges account for only a small proportion of all suicide deaths in Toronto and that results from one city may not match experiences elsewhere.

Introduction

Means restriction is arguably the population-based suicide prevention strategy with the most robust evidence base.1–5 Restricting access to common methods of suicide is thought to disrupt the suicide process because suicidal crises may be short-lived and people often report a preference for specific means.6–9 Critical reviews of the literature suggest only a small risk of people seeking out other ways to die from suicide once a specific method is no longer available.6 10

Special attention has been given to suicide by jumping from height with suicide prevention barriers constructed at the Empire State Building, the Eiffel Tower and bridges around the world11–15 including the Bloor Street Viaduct in Toronto, Canada, the second most frequented bridge worldwide for suicide death after the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.16 Our group studied the impact of the barrier 4 years after it was completed and demonstrated that, although there had been no further suicide deaths at the Bloor Street Viaduct, the number of suicide deaths by jumping from a height in Toronto was unchanged due to a statistically significant rise in suicide deaths at other bridges.16 This finding is in contrast to those from a meta-analysis conducted by Pirkis et al examining six studies which showed that, despite a 44% increase in suicide deaths at other jumping sites, barriers still resulted in a 28% net reduction of suicide deaths by jumping in the study cities.17

Suicide barriers are prominent, visible and often controversial interventions that may garner substantial attention from the media.14 16 18 This is notable given the well described ‘Werther Effect’ in which media reporting on suicide is thought to have a causal relationship with increased rates of death in an area through social contagion.19 Media reporting specifically on suicide by jumping has been positively associated with suicide rates and therefore may be particularly likely to result in contagion effects.20 Given evidence that media reporting on deaths at particular jumping sites encourages ‘copycat’ behaviour,21 it is plausible that such media reports occurring proximal to the construction of a suicide barrier may have a similar impact.

The construction of a suicide barrier therefore may function as a population-based natural experiment that ‘tests’ two potentially opposing impacts on suicide death; that is, it may test the value of a means restriction strategy designed to reduce suicide deaths as well as the impact of the consequent media discussion that may inadvertently increase them. Longer term data are needed to disentangle these phenomena given that media effects would be expected to be more transient compared with the barrier itself. Such an opportunity exists given that it has now been 13 years since the Bloor Street Viaduct suicide barrier was constructed and that, at the time, it garnered substantial media attention.16 In this study, we re-examine suicide deaths in Toronto as well as their relationship to media reporting to make a more definitive assessment of the barrier’s long-term impact. We maintained the a priori primary hypothesis of our original study that the barrier would result in fewer suicides by jumping in Toronto.

Methods

Suicide data

We examined records from the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario covering all suicide deaths in Toronto, extending our own previous analyses to examine long-term data.16 22 To be included in the data collection the death had to occur between 1 January 1993 and 31 December 2014 and be ruled a suicide by the coroner’s office. As it takes more than 1 year for a case to be closed, complete data for 2014 were available only in 2016. The coroner provided the following information for suicide deaths in Toronto in spreadsheet form: date of suicide, age, sex and cause of death, such as a fall or jump from a height, hanging or self-poisoning. All charts were then manually reviewed by the primary investigator and/or a trained research assistant to extract further pertinent data. We grouped the suicide deaths into three categories: all suicides in Toronto, suicides in Toronto by jumping (where jumping implied from a height, therefore people who jumped in subways were considered to have died by other means) and suicides in Toronto by means other than jumping. Suicide deaths by jumping were further categorised based on whether jumping occurred from a bridge or building (where building was defined as all other structures such as residential/office buildings, parking garages and hospitals). For suicide deaths by jumping from a bridge, we also obtained the location of the bridge where the suicide occurred. A prominent, nearby bridge of similar size was considered the ‘nearest comparison bridge’. Walking distance bridges were defined as those within 5 km of the Bloor Street Viaduct by foot. This was established using a Google directions search.

The barrier at the Bloor Street Viaduct was completed in 2003. Accordingly, we classified the 11 years from January 1993 to December 2003 as being before the barrier and the 11 years from January 2004 to December 2014 as being after the barrier. The population of Toronto was obtained from census data held by Statistics Canada for the years 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2011.23–25 We used these data to correct suicide rates for population over time according to methods used previously.16 Linear population growth was assumed for the periods 1996–2001, 2001–2006 and 2006–2011. We estimated population growth by extrapolating backwards from 1993 to 1996 and forwards from 2011 to 2014.

Media data

A media tracking service, Infomart, a division of Postmedia one of Canada’s largest news organisations, provided media articles related to suicide. After examining circulation volumes, a natural cut-off identified 11 local and national publications with the highest circulation in the Toronto media market: print and online version of three major Canadian newspapers (Globe & Mail, National Post, Toronto Star); print versions of the Toronto Sun, 24 hours Toronto, the New York Times, Maclean’s Magazine; online version of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (www.cbc.ca). Articles were available from 1997 for the Toronto Star, Toronto Sun, National Post and Maclean’s Magazine. The Globe & Mail and its online version were reliably available in 2000, the New York Times in 2004, www.cbc.ca in 2005, www.thestar.com and www.nationalpost.com in 2007 and 24 Hours Toronto in 2008. A database search was run for suicide and related keywords. Coders were trained to manually examine each article and include as relevant articles with a major focus on suicide, defined as having greater than two sentences or a short paragraph devoted to the subject. Trained coders then searched the identified articles for the keywords ‘Viaduct’, ‘Bridge’ and ‘Jump’. Identified articles were then coded on a yes/no basis for whether they (1) were related to the Bloor Street Viaduct, (2) if so, if they expressed negative views about the barrier or suicide barriers in general (defined as describing the barrier as a poor use of resources, an ineffective strategy or both) and/or included the cost of the barrier, (3) were related to jumping from a bridge other than the Bloor Street Viaduct and/or (4) included a message of hope that suicide is preventable. None of these codes were mutually exclusive. Five inter-rater reliability tests were spaced throughout coding, and collectively, 94% agreement was achieved.

Statistical analysis

Poisson regression analyses accounting for overdispersion (variance greater than mean) were used to examine differences between suicide rates before and after the barrier with time (prebarrier/postbarrier) and population adjusted suicide deaths per year as the independent and dependent variables, respectively. For the media analysis, Poisson regression were run to compare the population-adjusted counts of suicide per year in relation to the yearly number of articles. Because of the risk that media reports on a given year could be the result of specific deaths rather than the cause of them, the models applied a 1 year lag on the article predictor variable. That is, the analysis tested whether media occurrences on the previous calendar year had any relationship with suicide deaths. We considered a p value less than 0.05 to be statistically significant. All analyses were run using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute).

Results

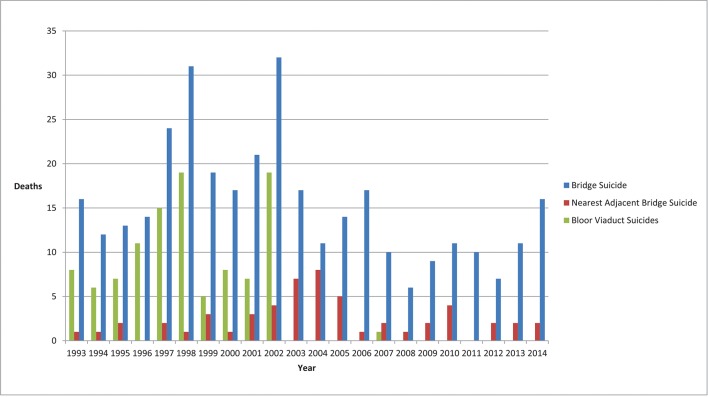

Rates of suicide before and after the suicide barrier are presented in table 1. Only one person has died by circumventing the barrier and jumping off the Bloor Street Viaduct since the barrier was completed. Per-capita rates at that location have declined from 9.0 deaths per year before the barrier to 0.1 deaths per year after the barrier (p=0.002). Suicide deaths from bridges in Toronto have also declined by a similar absolute number (18.8 deaths per year before the barrier vs 10.0 deaths per year after the barrier, p<0.0001). Counts of suicide deaths from the Bloor Street Viaduct and other bridges including the nearest comparison bridge are shown in figure 1. There has been no statistically significant rise in deaths by jumping from other bridges in the city overall, walking distance bridges, the nearest comparison bridge or from buildings. There was a numeric but non-significant reduction in overall suicide deaths by jumping (57.0 deaths per year before the barrier vs 51.3 deaths per year after the barrier, p=0.07). Suicide deaths from the nearest comparison bridge rose in the years during which the barrier was constructed and in the 2 years afterwards, but suicide deaths at that location have since declined to prebarrier levels. Per capita rates of suicide overall and by means other than jumping have also declined significantly over the study period (p<0.0001; p=0.001, respectively).

Table 1.

Poisson regression analysis of yearly suicide rates by jumping from height and by other means in Toronto prebarrier (1993–2003) and postbarrier (2004–June 2014)

| Subgroup | Suicides prebarrier mean number per year |

Suicides postbarrier mean number per year |

Regression coefficient | SE | p Value | IRR (95% CI)* | ||

| Observed | Corrected† | Observed | Corrected† | |||||

| Toronto (total) | 257.0 | 247.8 | 234.2 | 211.7 | −0.16 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.93) |

| Jumping | 59.3 | 57.0 | 56.7 | 51.3 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.01) |

| Building | 39.6 | 38.1 | 45.5 | 41.2 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.24) |

| Bridge | 19.6 | 18.8 | 11.1 | 10.0 | −0.63 | 0.15 | <0.0001 | 0.53 (0.40 to 0.71) |

| Bloor Street Viaduct | 9.5 | 9.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −4.68 | 1.54 | 0.002 | 0.009 (0.0005 to 0.19) |

| Other bridges | 10.1 | 9.6 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.84 | 1.03 (0.76 to 1.40) |

| Walking distance bridges | 6.7 | 6.3 | 5.5 | 5.0 | −0.24 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.79 (0.48 to 1.30) |

| Nearest comparison bridge | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.77 | 1.11 (0.54 to 2.29) |

| Other means | 197.7 | 190.8 | 177.5 | 160.4 | −0.17 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93) |

*IRR of suicides postbarrier compared with prebarrier; df=15.

Corrected per capita to suicides per 1993 population; not age standardised.

IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Figure 1.

Counts of suicide deaths at the Bloor Street Viaduct, the nearest comparison bridge and from all bridges in Toronto from 1993 to 2014.

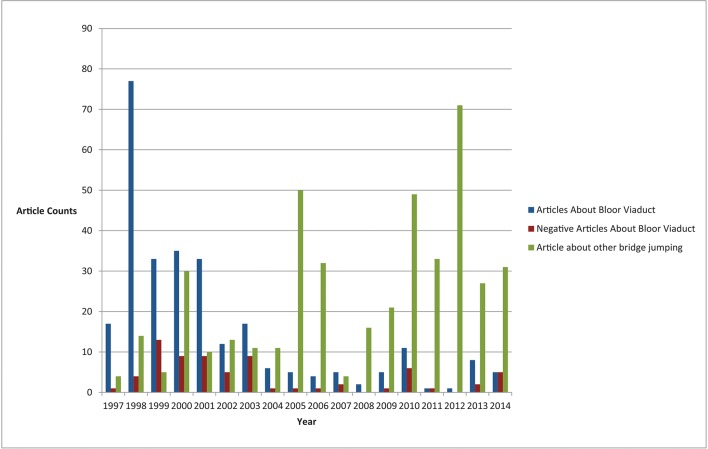

Counts of media articles about the Bloor Street Viaduct, those that expressed negative views about the barrier and those about suicide by jumping from other bridges are shown in figure 2. Over the 3 years prior to the barrier and the 2 years during its construction (1998–2003), there were 207 articles published about the Bloor Street Viaduct and its relationship to suicide including 96 (46%) that highlighted the cost of the barrier and 49 (24%) that expressed negative sentiments about the barrier. These included statements suggesting that the barrier was a waste of money or time, that resources should have been allocated elsewhere and/or that individuals at risk would simply find another way to end their lives.

Figure 2.

Counts of articles appearing in the 11 largest print and online media sources in Toronto relating to the Bloor Street Viaduct suicide barrier and suicide by jumping from other bridges from 1997 to 2014.

There was no significant relationship between number of articles and suicide deaths by jumping or overall in the following year. Articles about suicide at the Bloor Street Viaduct were associated with a significant increase in suicide deaths by jumping from bridges the following year (incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.011, 95% CI 1.0014 to 1.0207, p=0.02). These articles were also associated with a decline in suicide deaths by jumping from buildings the following year (IRR 0.9939, 95% CI 0.9902 to 0.9976, p=0.001). Articles describing the cost of the barrier were associated with an increase in suicides on bridges (IRR 1.025, 95% CI 1.0001 to 1.05, p=0.05). Messages of hope were associated with a decrease in suicide deaths by jumping from buildings only (IRR 0.9869, 95% CI 0.9776 to 0.9962, p=0.006). There was no significant impact of articles expressing negative views about the suicide barrier or articles about bridges other than the Bloor Street Viaduct.

Discussion

Only one person has managed to circumvent the barrier and die by suicide at the Bloor Street Viaduct over 11 years, consistent with the earlier, short-term finding that the barrier is effective at preventing suicide deaths at that location.16 What this study adds is the long-term data showing that suicide deaths from all bridges in Toronto have declined by a similar number to those prevented at the Bloor Street Viaduct with no increases in deaths at nearby bridges. These results differ substantially from the earlier, short-term findings. Likewise, the number of suicide deaths by jumping from all heights in Toronto had been unchanged after 4 years, whereas at 11 years after the barrier, there has been a numerical reduction (57.0 vs 51.3 deaths/year) with a trend towards significance (p=0.07).

The media results support the notion that the spike in suicide deaths observed at other bridges immediately after the barrier was influenced by short-term media reporting including some that expressed scepticism about the use of the barrier. Ironically, it appears that the negative impact of these speculative reports on suicide rates may have obscured the positive impact of the actual suicide prevention barrier leading to the short-term conclusion that it had not achieved its intended aim. This finding has important implications for how and when we evaluate the impact of future barriers in other locations.

Strengths and limitations

Our original study examined 4 years of data after the barrier under the premise that a barrier is an intervention that ought to have its maximum impact right after its creation. However, the results of that study were not in keeping with what has been observed at other suicide barrier locations,17 and they have been criticised for possibly being inadequately powered and for relying on a small number of years that might have been vulnerable to annual variability due to factors such as media effects.26 A major strength of the present study is the number of years examined postbarrier. This was intended to address the above concerns and to determine whether long-term outcomes were different and, indeed, they have been. The barrier also provided a unique opportunity to examine the Werther Effect. Most of the literature concerning suicide contagion examines suicide rates in the immediate weeks following specific suicide deaths.27 The media ‘event’ of the Bloor Street Viaduct as a suicide hotspot has been ongoing but variable in intensity over the years of the study. Rather than examining a transient impact of articles in the weeks immediately following them, this circumstance allowed for the use of a 1-year lag to determine the longer term impact of media reports. And indeed, even over years, a Werther Effect was observed.

This study has several important limitations. The most important is a potential ecological fallacy. As an uncontrolled natural experiment, it is possible that factors we were unable to account for may have impacted suicide rates. For example, although we were able to control for population growth per capita, we could not control for other population-based factors such as knowledge of the Bloor Street Viaduct as a suicide hotspot or societal changes that might have impacted on chosen suicide methods. The changing immigrant and ethnic composition of the city, in particular, may account for a portion of the overall reduction in suicide rates.28 This study did not examine the impact of economic changes nor did it seek to identify all other suicide prevention interventions occurring in Toronto. We were also only able to examine print and online media sources. We speculate that these should serve as a proxy for other types of media reporting including television and radio reports although this was not definitively established. Finally, we cannot rule out that a small number of suicide deaths by jumping from bridges or buildings in Toronto were either never identified or were misclassified by the coroner as accidental or due to homicide.

Despite the fact that the Bloor Street Viaduct had been one of the most frequented suicide hotspots in the world, the yearly number of deaths at that location is still only a small proportion of all suicide deaths in Toronto. Although there has been a near absence of deaths at that location after the barrier, it remains a challenge to demonstrate statistically significant impacts on rates of suicide deaths by jumping and by all methods in Toronto. Nevertheless, the results of this study suggest that a substantial proportion of those people who have been prevented by the barrier from dying at the Bloor Street Viaduct may not have gone on to end their lives in other locations and ways.

Conclusions

This study has important implications for future barriers being considered in other locations. It contributes to a convergence of evidence in the scientific literature demonstrating that barriers can be an effective means of preventing suicide deaths. They are a necessary component of a suicide prevention strategy but are also insufficient standalone interventions. Jurisdictions contemplating barriers should consider pairing their construction with media education about best practices in reporting and the possibility of copycat deaths. We further speculate that short-term outcomes in Toronto might have been different had the Bloor Street Viaduct barrier been accompanied by proactive messaging that dispelled common myths about suicide, emphasised that it is preventable, noted that the barrier is a sign that society cares about people contemplating suicide and provided information about high-quality mental healthcare services available nearby. Finally, researchers of future barriers should take note that transient increases in suicide deaths at other adjacent bridges may not be sustained in the long term. This should introduce a note of caution in interpreting and generalising results from the years immediately following a barrier’s construction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr James Edwards (regional supervising coroner for Toronto East) and the entire staff at the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario, including Andrew Stephen, for making this research possible. We further thank Infomart for providing the media data. We also thank Catherine Reis and Michelle Messner for their help with data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS developed the idea for this study, contributed to the study design, analysed the data, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. He is the guarantor. AS, DAR, AHC, AJL and JP contributed to the study design, interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript. AK contributed to the study design, analysed the data and critically revised the manuscript. YN contributed to the study design, data acquisition, interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This work was supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the University of Toronto, Department of Psychiatry Excellence Fund.

Competing interests: MS has received grant support from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation, the Dr Brenda Smith Bipolar Fund, the University of Toronto, Department of Psychiatry Excellence Fund and the Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan from the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario. AS has received funding from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation, the Dr Brenda Smith Bipolar Fund, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Sunovion, Otsuka and Lundbeck. AHC has received grant support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario Sport Support Unit, the Ontario Mental Health Foundation and the Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan from the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board (ID# 021-2011).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:646–59. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawton K, Suicide vanHK. Lancet 2009;373:1372–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gunnell D, Middleton N, Frankel S. Method availability and the prevention of suicide--a re-analysis of secular trends in England and Wales 1950-1975. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2000;35:437–43. 10.1007/s001270050261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294:2064–74. 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Cheung AH, et al. Means Restriction as a Suicide Prevention Strategy: Lessons Learned and Future Directions. pp. 94-102 In: Cutcliffe JR, Santos J, Links P, eds “Routledge International Handbook of Clinical Suicide Research”, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daigle MS. Suicide prevention through means restriction: assessing the risk of substitution. A critical review and synthesis. Accid Anal Prev 2005;37:625–32. 10.1016/j.aap.2005.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Florentine JB, Crane C. Suicide prevention by limiting access to methods: a review of theory and practice. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1626–32. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosen DH. Suicide survivors. A follow-up study of persons who survived jumping from the Golden Gate and San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridges. West J Med 1975;122:289–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seiden RH. Where are they now? A follow-up study of suicide attempters from the Golden Gate Bridge. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1978;8:203–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sarchiapone M, Mandelli L, Iosue M, et al. Controlling access to suicide means. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:4550–62. 10.3390/ijerph8124550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bennewith O, Nowers M, Gunnell D. Effect of barriers on the Clifton suspension bridge, England, on local patterns of suicide: implications for prevention. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:266–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.027136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gunnell D, Nowers M. Suicide by jumping. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;96:1–6. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09897.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pelletier AR. Preventing suicide by jumping: the effect of a bridge safety fence. Inj Prev 2007;13:57–9. 10.1136/ip.2006.013748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reisch T, Michel K. Securing a suicide hot spot: effects of a safety net at the Bern Muenster Terrace. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2005;35:460–7. 10.1521/suli.2005.35.4.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zarkowski P. The aurora bridge. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:1126 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sinyor M, Levitt AJ. Effect of a barrier at Bloor Street Viaduct on suicide rates in Toronto: natural experiment. BMJ 2010;341:c2884 10.1136/bmj.c2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pirkis J, Spittal MJ, Cox G, et al. The effectiveness of structural interventions at suicide hotspots: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:541–8. 10.1093/ije/dyt021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beautrais AL. Effectiveness of barriers at suicide jumping sites: a case study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001;35:557–62. 10.1080/0004867010060501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pirkis J, Blood RW. Suicide and the media. Part I: Reportage in nonfictional media. Crisis 2001;22:146–54. 10.1027//0227-5910.22.4.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Niederkrotenthaler T, Voracek M, Herberth A, et al. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: werther v. Papageno effects. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:234–43. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beautrais A. Suicide by jumping: a review of research and prevention strategies. Crisis 2007;28(Suppl 1):58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Streiner DL. Characterizing suicide in Toronto: an observational study and cluster analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59:26–33. 10.1177/070674371405900106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Statistics Canada. Population and dwelling counts, for Canada and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses. 2011. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table-Tableau.cfm?T=301&S=3&O=D; (accessed 17 Dec 2015).

- 24. Statistics Canada. Toronto, Ontario (Code3520) (table). 2006 Community Profiles. 2006 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 92-591-XWE. Ottawa. 2007 http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/92-591/index.cfm?Lang=E;.

- 25. Statistics Canada. Population and dwelling counts, for Canada and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2001 and 1996 censuses. 2001 Census, 2001. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/profil01/CP01/Details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CD&Code1=3520&Geo2=PR&Code2=35&Data=Count&SearchText=toronto&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&Custom=; (accessed 9 May 2016).

- 26. Sakinofsky I. Barriers to suicide. strategies at Bloor Viaduct. BMJ 2010;341:c4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sisask M, Värnik A. Media roles in suicide prevention: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:123–38. 10.3390/ijerph9010123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malenfant E. "Suicide in Canada¹s Immigrant Population." Health Reports, Vol. 15, No. 2, Statistics Canada, Catalogue. 2004:82–3. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.