Abstract

Objective

Seven recombinant viral capsid antigen-IgA (VCA-IgA) ELISA kits are widely used in China, but their diagnostic effects have not been evaluated. In this study, we evaluated whether the diagnostic effects of these kits are similar to those of the standard kit (EUROIMMUN, Lübeck, Germany).

Methods

A diagnostic case–control trial was conducted with 200 cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and 200 controls from NPC-endemic areas in southern China. The areas under the curve (AUCs), the sensitivities and the specificities of testing kits were compared with those of the standard kit. The test–retest reliability of each kit was determined by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Their diagnostic accuracy in combination with Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1-IgA (EBNA1-IgA) was also evaluated in logistic models.

Results

Three testing kits—BB, HA and KSB—showed diagnostic accuracy equal to that of the standard kit, with good performance in the AUCs (0.926–0.945), and no significant differences in sensitivity were found between early-stage and advanced-stage NPCs. ICCs exceeded 0.8. Three logistic regression models were built, and the AUCs of these models (0.961–0.977) were better than those of the individual VCA-IgA kits. All new models had diagnostic accuracy equal to that of the standard kit. New cut-off values of these three kits and their corresponding combinations for researchers to replicate and use in NPC early detection and screening in the future were provided.

Conclusions

Three recombinant VCA-IgA kits—BB, HA and KSB—had diagnostic effects equal to those of the standard kit, and, in combination with EBNA1-IgA in logistic regression models, can be used in future screening for NPC.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Epstein-Barr virus, VCA-IgA, Diagnostic effect, Screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to carry out a comprehensive evaluation of recombinant commercial diagnostic viral capsid antigen-IgA (VCA-IgA) (ELISA) kits in China, and logistic models combining VCA-IgA with Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1-IgA were established.

New cut-off values for VCA-IgA kits and their corresponding combinations for researchers to replicate and use in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) early detection and screening in the future were provided.

All cases and controls were from NPC-endemic areas of southern China, and thus, these results might not be applicable to other populations.

Only 33 early-stage NPC cases were collected. Controls were recruited from rural area, but half of the NPC cases were from urban areas.

Cut-off values for NPC screening by means of these models described in this study must be verified in prospective mass screening.

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a common form of squamous cell carcinoma in southern China and Southeastern Asia. The annual incidence rate of NPC in southern China can reach 25 per 100 000 person-years, which is about 25-fold higher than in the rest of the world.1–4 NPC is a complex disease caused by a combination of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), chronic infection, the environment and host genes in a multistep process of carcinogenesis, but until now there have been no effective preventive measures.5–9 Long-term survival rates differ substantially between patients with advanced-stage (stages III and IV) and early-stage NPC (stages I and II). Four-year survival rates of patients with early-stage NPC are 96.7% compared with 67.1% for those with advanced-stage NPC.5 Mass screening has become the most practical method for improved early detection in, and overall prognosis of, patients with NPC in the endemic areas.10 11

Serum antibodies against EBV-related antigens, especially IgA against viral capsid antigen-IgA (VCA-IgA), early antigen-IgA, EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1-IgA) and so on, remain elevated for an average of 38 months in the preclinical phase,9–14 and serological tests for these markers are simple and inexpensive.15–18 Therefore, since the 1970s, these tests have been used as screening markers for NPC in endemic areas. In our previous study, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of seven commercial EBV-related antibodies by ELISA and found EBNA1-IgA (Zhongshan Biotech, China) and VCA-IgA (EUROIMMUN, Lübeck, Germany) ELISA to be the top two seromarkers, with areas under the curve (AUC) of 0.95 (95%CI 0.93 to 0.97) and 0.94 (95%CI 0.92 to 0.97), respectively.16 We further verified that the combination of VCA-IgA and EBNA1-IgA outperformed any individual EBV seromarkers, with AUC up to 0.97 (95% CI 0.96 to 0.99).15–17 Thus, since 2011, the combination of VCA-IgA and EBNA1-IgA has been recommended as the standard tool for NPC screening in China.18

Nowadays, several kinds of commercial VCA-IgA kits based on recombinant peptides have been developed in China and are presently widely used for the early detection of and screening for NPC. However, their diagnostic performance for NPC alone and in combination with EBNA1-IgA has not been evaluated. In this study, we evaluated whether the effects of the NPC-diagnostic kits are comparable to those of the standard VCA-IgA kit and can be substituted for it. If so, we will further explore the combination diagnostic strategy with EBNA1-IgA for the early detection of and mass screening for NPC.

Methods

Study population

Serum specimens were continuously collected from 200 patients with NPC hospitalised in the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC) from January 2013 to June 2013. These cases were histologically confirmed by biopsy, and the clinical stages were classified according to the 2009 Union for International Cancer Control criteria, including 33 patients with early-stage NPC (stages I and II) and 167 with advanced-stage NPC (stages III and IV). The inclusion criteria included being between 30 and 59 years of age and residing in one of the six high-endemic provinces of southern China (Guangdong, Guangxi, Jiangxi, Hunan, Fujian or Hainan Province). Other information, including demographic data, smoking, drinking histories and family history of NPC, was collected by the physician in charge. All serum samples were collected before treatment.

The 200 healthy controls were randomly selected from among healthy people who participated in physical examinations at the Sihui Cancer Center (Sihui City, Guangdong Province, China) from July 2013 to September 2013 and were frequency matched with cases by age (5-year age groups) and gender. All participants completed a short questionnaire to record demographic data, smoking, drinking histories and family history of NPC and donated 3 mL of blood.

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the SYSUCC (YB2015-029-01), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Detection of serological EBV antibodies

Serum and buffy coat were separated <4 hours after collection and stored at −80°C before being tested. None of the specimens was haemolytic or repeatedly frozen more than twice. Seven recombinant VCA-IgA kits, the standard VCA-IgA kit (EUROIMMUN) and the standard EBNA1-IgA kit (Zhongshan) were tested (table 1).

Table 1.

Product information for eight brands of VCA-IgA kits and the EBNA1-IgA kit

| Abbreviation for kits | Manufacturer |

| VCA-IgA | |

| KSB | Shenzhen Kang Sheng Bao Bio-Technology |

| BNV | Bioneovan |

| GBI | Beijing BGI-GBI Biotech |

| BB | Beijing Beier Bioengineering |

| HA | Shenzhen HuianBioscitech |

| HK | Shen Zhen HuaKang |

| ZS | ZhongShan Biotech |

| EUROIMMUN | EUROIMMUN Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG |

| EBNA1-IgA | ZhongShan Biotech |

EBNA, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen; VCA, viral capsid antigen.

All samples were renumbered and tested blindly by one technician according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Levels of antibodies were assessed by photometric measurement, which provided optical density (OD) values. Reference ODs (rODs) were obtained according to the manufacturers’ instructions by dividing OD values by a reference control. To investigate the test–retest reliability of each kit, 10% serum samples (40 samples) were randomly chosen and retested.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics and NPC risk factors between cases and controls were compared by χ2 tests. The cut-off value of each single kit was defined with the largest Youden Indices (sensitivity+specificity−1) chosen from each receiver operating characteristic (ROC). The diagnostic efficacy of each kit was evaluated by AUC, and non-inferiority tests based on the bootstrap approach were performed to determine whether the AUCs of these recombinant testing kits were inferior to that of the standard kit (let Δ=0.05 be the predetermined clinically meaningful equivalence limit).19–22 The sensitivity and specificity of each kit were calculated and their 95% CIs were estimated by the methods of Simel et al 23 (The 95% CIs of sensitivities for early-stage groups were estimated by lookup table method for binomial distribution because the sample size was less than 50).24 Differences in sensitivities between early-stage and advanced-stage NPC with each kit were compared by χ2 tests (Fisher’s exact test and McNemar’s test will be specified while χ2 tests means Pearson’s χ2 test). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were performed to determine test–retest reliability.

To prevent bias and study the virus factor only, we matched the baseline covariates (gender and age) and some of the important NPC risk factors (smoking, drinking and NPC history). Binary unconditional logistic regressions were used to establish formulae for VCA-IgA and EBNA1-IgA. The diagnostic efficacy of each formula was evaluated by sensitivity, specificity and AUC, compared with the standard formula, Logit p=−3.934+2.203 VCA-IgA (EUROIMMUN)+4.797 EBNA1-IgA. The cut-off p value in the corresponding logistic regression for distinguishing between NPC cases and controls was defined with the largest Youden Index chosen from each ROC. Two minimally acceptable false-positive rates (1-specificity), 3% and 7%, were used empirically to establish the cut-off p values for classifying different NPC risk subgroups.16 17

The non-inferiority tests were one sided, and p>0.05 was considered to be non-inferior. Other tests were two sided, and p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data were analysed by SAS V.9.2 and SPSS V.16.0 software.

Results

Baseline information

Baseline information on gender, age, smoking, drinking and NPC family history was comparable between cases and controls, and no statistically significant differences were found between them. Further, there were no statistically significant differences for these items between early-stage and advanced-stage cases (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of NPC cases and controls

| Categories | NPC cases (N1=200), n (%) | Controls (N2=200), n (%) |

p Value† | |||

| Early stage (n=33) | Advanced stage (n=167) | p Value* | Total | |||

| Gender | 0.472 | 0.417 | ||||

| Male | 27 (81.8) | 127 (76.0) | 154 (77.0) | 147 (73.5) | ||

| Female | 6 (18.2) | 40 (24.0) | 46 (23.0) | 53 (26.5) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.299 | 0.785 | ||||

| ~30 | 6 (18.2) | 47 (28.1) | 53 (26.5) | 47 (23.5) | ||

| ~40 | 13 (39.4) | 70 (41.9) | 83 (41.5) | 87 (43.5) | ||

| ~50 | 14 (42.4) | 50 (29.9) | 64 (32.0) | 66 (33.0) | ||

| Smoking‡ | 0.857 | 0.746 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (33.3) | 53 (31.7) | 64 (32.0) | 61 (30.5) | ||

| No | 22 (66.7) | 114 (68.3) | 136 (68.0) | 139 (69.5) | ||

| Drinking§ | 0.641 | 0.494 | ||||

| Yes | 6 (18.2) | 25 (15.0) | 31 (15.5) | 27 (13.5) | ||

| No | 27 (81.8) | 142 (85.0) | 169 (84.5) | 173 (86.5) | ||

| NPC family history¶ | 0.732 | 0.224 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (9.1) | 13 (7.8) | 16 (8.0) | 10 (5.0) | ||

| No | 30 (90.9) | 154 (92.2) | 184 (92.0) | 190 (95.0) | ||

*Differences in early-stage and advanced-stage NPC were compared by χ2 tests (Fisher’s exact test for NPC family history). p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

†Differences in NPC cases and controls were compared by χ2 tests. p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

‡Smoking refers to people who smoked more than one cigarette every 3 days within half a year and included current and former smokers.

Drinking refers to people who consumed alcoholic beverages every week within half a year and included current and former drinkers.

NPC family history refers to people whose parents, children and siblings have or did have NPC.

NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

The diagnostic accuracies of eight brands of VCA-IgA kits and the EBNA1-IgA kit

Table 3 shows that the AUCs of four kits—KSB, BB, BNV and HA—were as high as that of the standard VCA-IgA kit (AUC 0.942; 95% CI 0.920 to 0.964). The AUCs, in order, were 0.945 for KSB (95% CI 0.925 to 0.966), 0.940 for BB (95% CI 0.916 to 0.964), 0.936 for BNV (95% CI 0.911 to 0.961) and 0.926 for HA (95% CI 0.900 to 0.953). In addition, the AUCs of GBI, HK and ZS were lower than that of the standard kit. Furthermore, no significant differences were found between early-stage and advanced-stage NPC in the sensitivities of six kits (p>0.05), except for BNV (p=0.044).

Table 3.

The diagnostic accuracies of eight brands of VCA-IgA kits and the EBNA1-IgA kit in distinguishing between NPC cases and controls

| Kits | Cut-off values† | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC (95% CI) | p Value§ | ||

| Early stage (95% CI) | Advanced stage (95% CI)‡ | Total (95% CI) | Control (95% CI) | ||||

| VCA-IgA | |||||||

| BB | 0.58 | 75.8 (58.0 to 89.0) | 88.6 (84.2 to 93.0) | 86.5 (81.8 to 91.2) | 92.0 (88.2 to 95.8) | 0.940 (0.916 to 0.964) | 0.002 |

| BNV | 0.923 | 72.7 (54.0 to 87.0) | 88.0 (83.5 to 92.5)* | 86.0 (81.2 to 90.8) | 93.5 (90.1 to 96.9) | 0.936 (0.911 to 0.961) | 0.003 |

| GBI | 0.825 | 72.7 (54.0 to 87.0) | 76.6 (70.8 to 82.5) | 76.0 (70.1 to 81.9) | 92.0 (88.2 to 95.8) | 0.899 (0.868 to 0.930) | 0.341* |

| HA | 0.884 | 93.9 (80.0 to 99.0) | 88.0 (83.5 to 92.5) | 89.0 (84.7 to 93.3) | 86.0 (81.2 to 90.8) | 0.926 (0.900 to 0.953) | 0.012 |

| HK | 1.218 | 81.8 (64.0 to 93.0) | 83.2 (78.1 to 88.4) | 83.0 (77.8 to 88.2) | 89.5 (85.3 to 93.7) | 0.913 (0.884 to 0.942) | 0.075* |

| KSB | 0.283 | 100.0 (89.0 to 100.0) | 86.8 (82.1 to 91.5) | 89.0 (84.7 to 93.3) | 87.5 (82.9 to 92.1) | 0.945 (0.925 to 0.966) | 0.000 |

| ZS | 0.418 | 75.8 (58.0 to 89.0) | 74.3 (68.2 to 80.3) | 74.5 (68.5 to 80.5) | 87.5 (82.9 to 92.1) | 0.868 (0.831 to 0.904) | 0.878* |

| EUROIMMUN | 1.561 | 87.9 (72.0 to 97.0) | 85.6 (80.8 to 90.5) | 86.0 (81.2 to 90.8) | 90.0 (85.8 to 94.2) | 0.942 (0.921 to 0.964) | |

| EBNA1-IgA | 1.203 | 93.9 (80.0 to 99.0) | 86.2 (81.5 to 91.0) | 87.5 (82.9 to 92.1) | 92.5 (88.8 to 96.2) | 0.956 (0.937 to 0.975) | 0.000 |

†Cut-off value for NPC diagnosis was defined as the value with the largest Youden Index chosen from each ROC.

‡Differences in the sensitivities of early-stage and advanced-stage NPC were compared by Pearson’s χ2 tests. *p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

§p Values were estimated by non-inferiority tests based on the bootstrap approach for AUC between EUROIMMUN and other kits. *p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant, whereas p>0.05 was consider to be inferior to the standard kit.

AUC, areas under the curve; EBNA, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; VCA, viral capsid antigen.

The test–retest reliabilities of eight brands of VCA-IgA kits and the EBNA1-IgA kit

Ten per cent serum samples (40 samples) were randomly chosen and retested for calculation of the ICC of each brand of kit, VCA-IgA or EBNA1-IgA. The test–retest reliabilities of all kits were excellent (>0.75, excellent) according to Fleiss’s classification25 (table 4).

Table 4.

The test–retest reliabilities of eight brands of VCA-IgA kits and the EBNA1-IgA kit

| Kits | ICC* | 95% CI |

| VCA-IgA | ||

| BB | 0.990 | 0.980 to 0.994 |

| BNV | 0.982 | 0.967 to 0.991 |

| GBI | 0.964 | 0.933 to 0.981 |

| HA | 0.975 | 0.952 to 0.987 |

| HK | 0.876 | 0.764 to 0.935 |

| KSB | 0.823 | 0.666 to 0.906 |

| ZS | 0.978 | 0.958 to 0.988 |

| EUROIMMUN | 0.913 | 0.830 to 0.955 |

| EBNA1-IgA | 0.981 | 0.964 to 0.990 |

*Less than 0.40, poor; between 0.40 and 0.59, fair; between 0.60 and 0.74, good and between 0.75 and 1.00, excellent.

The diagnostic accuracies of the combinations of VCA-IgA and EBNA1-IgA with logistic models

We chose three VCA-IgA kits with high AUCs, no differences in diagnoses for early-stage and advanced-stage NPC and excellent test–retest reliabilities, and then combined each with the EBNA1-IgA kit by logistic models. Three logistic regression models were established:

LogitP = −3.2323+0.8060 VCA-IgA (BB)+1.1044 EBNA1-IgA

LogitP=−2.7591+0.6380 VCA-IgA (HA)+1.0620EBNA1-IgA

LogitP=−2.6039+0.5312 VCA-IgA (KSB)+1.1673 EBNA1-IgA

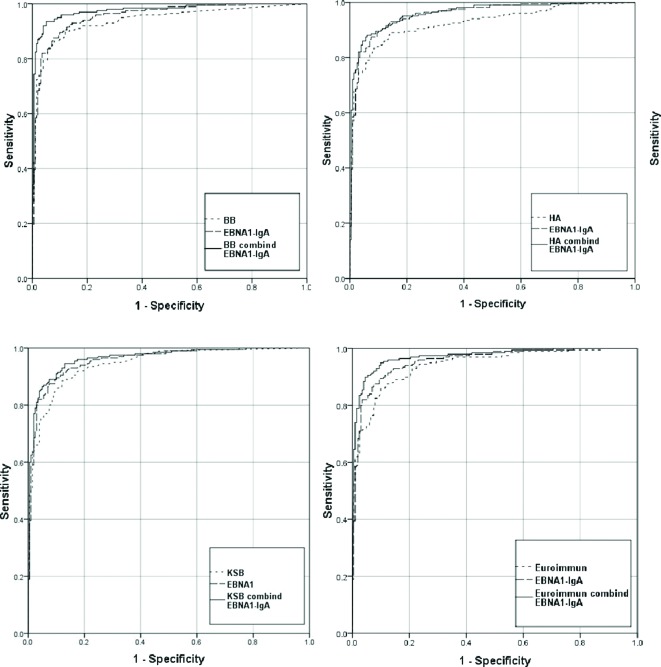

In all these models, both VCA-IgA and EBNA1-IgA were statistically significant independent predictors of NPC risk (p<0.05), and the AUC of each combination was statistically significantly larger than that of each single VCA-IgA (p<0.05). The AUC of KSB increased from 0.945 (95% CI 0.925 to 0.966) to 0.964 (95% CI 0.947 to 0.981); BB increased from 0.940 (95% CI 0.916 to 0.964) to 0.977 (95% CI 0.963 to 0.991) and HA increased from 0.926 (95% CI 0.900 to 0.953) to 0.961 (95% CI 0.943 to 0.979) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

ROCs for BB, HA, KSB, EUROIMMUN and their combination with EBNA1-IgA.

Table 5 shows the diagnostic accuracies of the three new combinations and the standard combination (Logit p=−3.934+2.203 VCA-IgA (EUROIMMUN)+4.797EBNA1-IgA) in distinguishing between NPC cases and controls. The AUCs of these three combinations were as high as that of the standard combination (AUC 0.970; 95% CI 0.956 to 0.985) (p<0.05). Furthermore, no statistically significant difference was found in the sensitivity of each combination between early-stage and advanced-stage NPC (p>0.05).

Table 5.

The diagnostic accuracies of the three new combinations and the standard combination in distinguishing between NPC cases and controls

| Combination | New cut-off values† | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC (95% CI) |

p Value§ | ||

| Early stage (95% CI) |

Advanced stage (95% CI)‡ |

Total (95% CI) |

Control (95% CI) |

||||

| BB+EBNA1-IgA | 0.258 | 97.0 (85.0 to 100) |

92.8 (89.2 to 96.4) |

93.5 (90.1 to 96.9) |

95.0 (92.0 to 98.0) |

0.977 (0.963 to 0.991) |

<0.001 |

| HA+EBNA1-IgA | 0.379 | 97.0 (85.0 to 100) |

86.2 (81.5 to 91.0) |

88.0 (83.5 to 92.5) |

94.0 (90.7 to 97.3) |

0.961 (0.943 to 0.979) |

<0.001 |

| KSB+EBNA1-IgA | 0.191 | 93.9 (80 to 100) |

94.6 (91.5 to 97.7) |

94.5 (91.3 to 97.7) |

87.0 (82.3 to 91.7)* |

0.964 (0.947 to 0.981) |

<0.001 |

| Standard combination | 0.998 | 97.0 (85 to 100) |

88.6 (84.2 to 93.0) |

90.0 (85.8 to 94.2) |

95.5 (92.6 to 98.4) |

0.970 (0.956 to 0.985) |

|

†New cut-off value for NPC diagnosis was defined as the value with the largest Youden Index chosen from each ROC.

‡Differences in the sensitivity of early-stage and advanced-stage NPC were compared by Pearson’s χ2 tests. p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

§p Values were estimated by non-inferiority tests based on the bootstrap approach for AUC between new combinations and the standard combination. p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant, whereas p>0.05 was consider to be inferior to the standard kit.

We used two minimally acceptable false-positive rates (1-specificity) of 3% and 7% to define the high-risk and medium-risk cut-off values for the new combinations. The corresponding logistic regression p values were 0.707 and 0.232 for BB, 0.766 and 0.364 for HA and 0.831 and 0.384 for KSB, and the corresponding true-positive rates (sensitivities) were 88.0% and 93.5% for BB, 78.0% and 88.0% for HA and 79.0% and 87.5% for KSB.

Discussion

In our study, seven recombinant VCA-IgA kits were evaluated, and of these, KSB, BB and HA had diagnostic effects as good as those of the standard kit in terms of sensitivity, specificity and AUC. Combining VCA-IgA with EBNA1-IgA by logistic regression models increased the diagnostic accuracy of these three kits, and all combinations performed as well as the standard combination in sensitivity, specificity and AUC. This is the first study to carry out a comprehensive evaluation of recombinant commercial diagnostic VCA-IgA (ELISA) kits in China, and logistic models combining VCA-IgA with EBNA1-IgA were established. Furthermore, new cut-off values for these VCA-IgA kits and their corresponding combinations for researchers to replicate and use in NPC early detection and screening in the future were provided.

In this study, we first calculated the diagnostic performance of each brand of VCA-IgA kit. The AUC of the standard VCA-IgA kit (EUROIMMUN) was 0.942 (95% CI 0.920 to 0.964), which was consistent with the results from our previous studies and verified that the diagnostic performance of VCA-IgA was good and stable.16 17 We also found that the sensitivities, specificities and AUCs of three kits—KSB, BB and HA—were as high as those of the standard kit, and no significant differences in sensitivity were found between early-stage and advanced-stage NPC. Moreover, all test–retest reproducibilities were excellent (>0.75) and the coefficient of variations of difference values of test and retest results of all assays were shown in supplementary table 1. These results suggested that these three kits had equal diagnostic effects and can be substituted for the standard kit. The costs of these recombinant commercial diagnostic kits were only half that of the standard kit, making them more cost effective.

bmjopen-2016-013211supp001.pdf (171.9KB, pdf)

The EBV capsid antigen (VCA) is a late protein produced in the EBV lytic infection period. VCA contains a batch of capsid proteins, such as VCA-p18 (BFRF3), VCA-p23 (BLRF2), gp125/110 (BALF4) and so on, which have unique immune dominants and virus-specific antigenic domains. These domains contain several small peptide regions (epitopes) which can be combined to form a powerful diagnostic reagent for VCA-IgA.26 27 The capsid proteins in the EUROIMMUN kit28 were extracted from the pyrolysis products of human B lymphocytes (P3HR1 cell line) infected by EBV and contained a combined native capsid protein of EBV. We noticed that, in contrast to the standard kit with a combined native capsid protein, these testing kits contain primarily recombinant p18 capsid proteins (VCA-p18). VCA-p18 is a small capsid protein that contains several small peptide regions (epitopes) which can be combined to form a powerful diagnostic reagent for VCA-IgA antibody responses.27 Some researchers have reported that VCA-p18 is the major VCA antigen for IgA responses.27 29 Our study showed that the AUCs of these VCA-p18 recombinant kits were more than 0.85, and three of them had the same diagnostic effects as the standard kit, suggesting that, although the manufacturing processes of some recombinant VCA-p18 kits still need to be improved, some of the recombinant kits can be substituted for the standard kit for NPC diagnosis.

As the serum antibody level (rOD) provides continuous data, the cut-off value for distinguishing between NPC cases and controls is critical for the early detection of and screening for NPC. A reasonable cut-off value can balance sensitivity and specificity. In the early detection of and screening for NPC, high sensitivity is required for the identification of high-risk individuals, and high specificity is required for reducing the rate of misdiagnosis and associated costs. According to the cut-off values provided by the kits’ instructions, the sensitivities of testing kits were always too low, whereas their specificities were always too high. For example, the sensitivity and the specificity of KSB are 0.780 and 0.925, respectively, suggesting that the old cut-off values should be adjusted (online supplementary table 2). We established new cut-off values for distinguishing between NPC cases and controls by Youden Indices, and then obtained reasonable sensitivities and specificities. After adjustment, the new cut-off value for KSB is 0.283, and the sensitivity and specificity are 0.890 and 0.875, respectively. Moreover, no differences were found between sensitivities and specificities of these three kits —KSB, BB and HA—and those of the standard kit. Due to the low percentage (<20%) of early stage in clinic, we can only collect 33 early-stage NPC participants in our study. Analysing the sensitivities by pooling early and late stage together only was not appropriate. So we did subgroup analysis and found there were also no statistically significant differences in the sensitivities of these three kits for early-stage and advanced-stage NPC. Furthermore, there were no differences between the early-stage sensitivities of these three kits and that of the standard kit too (0.202 for BB, 0.0672 for HA and 0.112 for KSB).

As for the standard VCA, we found that the combinations of VCA-IgA and EBNA1-IgA by logistic models increased the diagnostic accuracy for NPC from less than 0.946 to more than 0.961 in AUCs. Sensitivities and specificities also increased. For example, the sensitivity and specificity of BB increased from 0.865 and 0.920 to 0.935 and 0.955, respectively. VCA-IgA and EBNA1-IgA are two antibodies corresponding to EBV lytic-cycle proteins and latency gene products, respectively. Therefore, it is reasonable that host antibody responses for lytic-cycle and latency-associated EBV-related proteins can be complementary to each other in the diagnosis of NPC, and the combination of both could increase NPC diagnostic accuracy.11 30 Furthermore, these three new combinations had diagnostic effects in sensitivities (including subgroup analysis), specificities and AUCs equal to those of the standard combination, suggesting that the combinations of the three recombinant kits can be used for the early detection of and diagnostic screening for NPC. In this study, the control individuals came from NPC-endemic areas and belonged to a screening target population, so we attempted to define people at different risk levels by these new combinations for NPC screening. Compared with other common diseases, the NPC incidence rate in the screening target population was relatively low (about 50 per 100 000 person-years).2 10 31 Thus, it is important that the false-positive rate be small enough to avoid unnecessary fiberoptic endoscopy/biopsies and psychological stress for the NPC screening participants. Conversely, the true-positive rate (equal to sensitivity) should be acceptable.32 We used two minimally acceptable false-positive rates of 3% and 7% as the high-risk and medium-risk cut-off values, respectively,17 and the corresponding true-positive rates (sensitivities) for these three kits were 78.0%–88.0% and 87.5%–93.5%,5 respectively. If the baseline serologic results fulfilled the definition of high risk, the participants were referred for diagnostic examinations and different screening intervals were assigned to the high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk groups. The screening intervals for these groups are 1, 1 and 4 years, respectively.17

The study had some limitations. First, this study was a single-centre study and all cases and controls were from NPC-endemic areas of southern China (controls were from hospital); therefore, these results might not be applicable to other populations. Second, due to the low percentage (<20%) of early stage in clinic, we can only collect 33 early-stage NPC participants in our study period. But the phenomenon also indicated that most patients are typically not detected until NPC is in an advanced stage. Finding out such people was also very meaningful in real life. Third, controls were recruited from rural area, but half of the NPC cases were from urban areas (rural:urban=95:105). Although no evidence showed that there were different infection rates between rural and urban people, it might cause some other unknown bias. Fourth, it was a diagnostic trial in case–control design and new cut-off values of these new schemes for NPC screening from this study must be verified in prospective mass screenings.

Conclusions

Three recombinant VCA-IgA kits—BB, HA and KSB—had diagnostic effects equal to those of the standard kit. They can be substituted for the standard kit and their combinations could be used in the early detection of and screening for NPC.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: S-MC and QL obtained the funding; RG, LW and L-FZ contributed to study conception and design; RG conducted experiments; LW, Y-FY, J-LD, S-HX, S-HC, JG, M-JY and C-L acquired or cleaned the data; RG analysed and interpreted the data; RG, S-MC and QL drafted or revised the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code and dataset in main document are available from the corresponding author at caosm@sysucc.org.cn and liuqing@sysucc.org.cn.

References

- 1. Ma J, Cao S. The epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma : JJ L, Cooper JS, AWM L, Nasopharyngeal cancer. Berlin: Springer, 2010:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jia WH, Huang QH, Liao J, et al. Trends in incidence and mortality of nasopharyngeal carcinoma over a 20-25 year period (1978/1983-2002) in Sihui and Cangwu counties in southern China. BMC Cancer 2006;6:178–85. 10.1186/1471-2407-6-178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:1765–77. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin J Cancer 2011;30:114–9. 10.5732/cjc.010.10377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sarmiento MP, Mejia MB. Preliminary assessment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma incidence in the Philippines: a second look at published data from four centers. Chin J Cancer 2014;33:159–64. 10.5732/cjc.013.10010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jia WH, Collins A, Zeng YX, et al. Complex segregation analysis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Guangdong, China: evidence for a multifactorial mode of inheritance (complex segregation analysis of NPC in China). Eur J Hum Genet 2005;13:248–52. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu MC, Yuan JM. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol 2002;12:421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xue WQ, Qin HD, Ruan HL, et al. Quantitative association of tobacco smoking with the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies conducted between 1979 and 2011. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:325–38. 10.1093/aje/kws479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chien YC, Chen JY, Liu MY, et al. Serologic markers of Epstein-Barr virus infection and nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwanese men. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1877–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa011610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cao SM, Liu Z, Jia WH, et al. Fluctuations of Epstein-Barr virus serological antibodies and risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective screening study with a 20-year follow-up. PLoS One 2011;6:e19100 10.1371/journal.pone.0019100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeng Y, Zhong JM, Li LY, et al. Follow-up studies on Epstein-Barr virus IgA/VCA antibody-positive persons in Zangwu County, China. Intervirology 1983;20:190–4. 10.1159/000149391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen MR, Liu MY, Hsu SM, et al. Use of bacterially expressed EBNA-1 protein cloned from a nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) biopsy as a screening test for NPC patients. J Med Virol 2001;64:51–7. 10.1002/jmv.1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zong YS, Sham JS, Ng MH, et al. Immunoglobulin A against viral capsid antigen of Epstein-Barr virus and indirect mirror examination of the nasopharynx in the detection of asymptomatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer 1992;69:3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yi Z, Yuxi L, Chunren L, et al. Application of an immunoenzymatic method and an immunoautoradiographic method for a mass survey of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Intervirology 1980;13:162–8. 10.1159/000149121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang B, Liu Q, Cui Y, et al. Protocols of screening, early detection and diagnosis for nasopharyngeal carcinoma : Dong Z, Qiao Y, Protocols of screening, early detection and diagnosis for cancer in P.R.china. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House of P.R. China, 2009:187–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu Y, Huang Q, Liu W, et al. Establishment of VCA and EBNA1 IgA-based combination by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as preferred screening method for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a two-stage design with a preliminary performance study and a mass screening in southern China. Int J Cancer 2012;131:406–16. 10.1002/ijc.26380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Z, Ji MF, Huang QH, et al. Two Epstein-Barr virus-related serologic antibody tests in nasopharyngeal carcinoma screening: results from the initial phase of a cluster randomized controlled trial in southern China. Am J Epidemiol 2013;177:242–50. 10.1093/aje/kws404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Department of disease prevention and control, Ministry of health, China. Technical proposal for early diagnosis and treatment of cancer (2011) (Chinese). Peking: People’s Medical Publishing House (PMPH), 2011:144–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Obuchowski NA. Testing for equivalence of diagnostic tests. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;168:13–17. 10.2214/ajr.168.1.8976911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu JP, Ma MC, Wu CY, et al. Tests of equivalence and non-inferiority for diagnostic accuracy based on the paired areas under ROC curves. Stat Med 2006;25:1219–38. 10.1002/sim.2358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou XH, Obuchowski NA, McClish DK. Statistical methods in diagnostic medicine. New York: Wiley, 2002:188–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen WZ, Zhang JY. Application of non-inferiority test for diagnostic accuracy under the areas of ROC based on bootstrap approach and its macro programming development. Modern Prev Med 2010;37:3009–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:763–70. 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90128-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Medical statistics (Third edition) (Chinese). 93 Peking: People’s Medical Publishing House (PMPH), 2010:710. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fleiss JL. Reliability of measurement. The designand analysis of clinical experiments, 1st edn. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1986:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tang JW, Rohwäder E, Chu IM, et al. Evaluation of Epstein-Barr virus antigen-based immunoassays for serological diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Virol 2007;40:284–8. 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Middeldorp JM. Epstein-Barr virus-specific humoral immune responses in health and disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2015;391:289–323. 10.1007/978-3-319-22834-1_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mao Y-P, Li W-F, Chen L, et al. A clinical verification of the chinese 2008 staging system for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer 2009;28:1022–8. 10.5732/cjc.009.10425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Grunsven WM, Spaan WJ, Middeldorp JM. Localization and diagnostic application of immunodominant domains of the BFRF3-encoded Epstein-Barr virus capsid protein. J Infect Dis 1994;170:13–19. 10.1093/infdis/170.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fachiroh J, Paramita DK, Hariwiyanto B, et al. Single-assay combination of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) EBNA1- and viral capsid antigen-p18-derived synthetic peptides for measuring anti-EBV immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA antibody levels in sera from nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients: options for field screening. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:1459–67. 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1459-1467.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wei K, Xu Y, Liu J, et al. No incidence trends and no change in pathological proportions of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Zhongshan in 1970-2007. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2010;11:1595–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pepe MS, Feng Z, Janes H, et al. Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1432–8. 10.1093/jnci/djn326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013211supp001.pdf (171.9KB, pdf)