Abstract

Background

Bills have been put forward in the UK and Republic of Ireland proposing a move to Central European Time (CET). Proponents argue that such a change will have benefits for road safety, with daylight being shifted from the morning, when collision risk is lower, to the evening, when risk is higher. Studies examining the impact of daylight saving time (DST) on road traffic collision risk can help inform the debate on the potential road safety benefits of a move to CET. The objective of this systematic review was to examine the impact of DST on collision risk.

Methods

Major electronic databases were searched, with no restrictions as to date of publication (the last search was performed in January 2017). Access to unpublished reports was requested through an international expert group. Studies that provided a quantitative analysis of the effect of DST on road safety-related outcomes were included. The primary outcomes of interest were road traffic collisions, injuries and fatalities.

Findings

Twenty-four studies met the inclusion criteria. Seventeen examined the short-term impact of transitions around DST and 12 examined long-term effects. Findings from the short-term studies were inconsistent. The long-term findings suggested a positive effect of DST. However, this cannot be attributed solely to DST, as a range of road collision risk factors vary over time.

Interpretation

The evidence from this review cannot support or refute the assertion that a permanent shift in light from morning to evening will have a road safety benefit.

Keywords: systematic review, road safety, daylight saving time, collision risk.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review draws together evidence of the impact of shifting time zones on road traffic collision risk and is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review that can inform current debates on time-zone changes.

A key strength of this review is the examination of collision risk across different types of road users and time of day, reflecting the complex array of factors that are implicated in the relationship between light and collision risk.

Studies selected varying time periods around daylight saving time transitions for analyses, and used a range of analytic and statistical approaches. We were therefore unable to combine the findings through meta-analysis.

The long-term findings reported in this review are less relevant to the review question than the short-term findings, since a range of risk factors for road traffic collisions vary in the long-term (eg, traffic flow and weather conditions).

Introduction

In recent years, Bills such as the Brighter Evenings Bill have been put before parliaments in the UK and Republic of Ireland (henceforth 'Ireland') that, if enacted, would result in these jurisdictions changing time zone from Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) to Central European Time (CET). These jurisdictions would not be the first to adjust time zones. China historically changed time zones within its borders1 and, more recently, Russia2 and North Korea,3 among others, have experimented with time-zone changes. Currently, there are a number of countries, including Spain,4 contemplating similar shifts.

For the UK and Ireland, the change would impact on approximately 70 million people. In practice, it would mean that the sun would rise and set 1 hour later than at present, leading to darker mornings and brighter evenings. Proponents of the Bills argue that such a change would have economic benefits, arising from the alignment of the working day across neighbouring economic partners, and societal benefits, including a reduction in road traffic collisions, injuries and fatalities.5

The assertion that a move to CET would have a positive impact on road safety is rooted in the relationship between light and collision risk. It has been argued that road traffic collision risk is at its highest in the late afternoon and evening hours (15:00 to 19:00 hours) and that, on some level, this arises due to the interaction between deteriorating lighting conditions and other risk factors, including driver fatigue.6 7 To the extent that evening collision risk derives from poor light, shifting an hour of daylight from the morning, when collision risk is lower, to the evening, when collision risk is higher, should lead to an overall net reduction in road traffic collisions.5 8 9 This should be particularly marked during the autumn and winter months when the evenings are darker and weather conditions less favourable for road users.5

This argument has found some support in the empirical literature. Broughton and Stone, for example, have produced an authoritative study on the likely effects on road collisions of adopting single/double summer time (SDST, ie, CET) year-round. Using mathematical modelling procedures to estimate casualty incidence, they estimated that a move to CET would lead to an overall reduction in fatalities of between 2.6% and 3.4%, and a reduction in serious injuries of 0.7%.7 The UK’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents recently drew similar conclusions, arguing that any increase in a morning collision peak will be ‘more than off-set by the reduction in the higher evening peak’ (p1).5

The overall trends relating to collisions across time of day appear, at first glance, to support some of the core assumptions behind the CET argument. However, the extent to which collision risk is actually impacted by shifting light and time is unclear, and difficult to expose to scientific enquiry for a number of reasons. First, most of the UK studies on CET are based on data derived from the 1968–1971 British Standard Time (BST) experiment, during which the UK remained in daylight saving time (DST) year-round. As noted by the Transport Research Laboratory,7 ‘conditions have changed since the end of the experiment and the results cannot be applied directly to current conditions’ (p. 3). Specifically, there have been substantial changes in traffic levels, road infrastructure and road user behaviour in the past five decades that mean the 1968–1971 experiment may be of limited relevance today.

Second, evidence suggests that light is rarely a direct cause of collisions. Instead, light and darkness tend to compound more direct causal factors. For example, driver performance deteriorates under poor lighting conditions, due to diminished visual reaction times and impeded ability to process core information like critical stopping distances. Collisions in this context are caused by driver error—error that can occur under both ambient and dark conditions, but which is compounded under the latter.10 Similarly, light can interact with environmental factors, like rain, frost and snow, to inflate crash risk.

The impact of a move to CET is not easily estimated, given the complex array of factors implicated in collisions. One method for examining its potential impact is to look at transitions into and out of DST. DST refers to the practice of adjusting the clock time to create extra daylight during periods of waking activity.11 In the Northern Hemisphere, clocks are set forward by 1 hour in spring, providing an extra hour of daylight in the evenings, and revert back to standard time (ST) in the autumn, leading to an extra hour of daylight in the mornings. DST shifts provide a naturalistic experiment that can yield estimates as to the association between light and collisions. Particularly in the short-term (typically 1–2 weeks around the transitions), these estimates can be considered to account for the influence of traffic and pedestrian-flow, which are believed to be relatively stable over short periods of time. Long-term studies (typically 3–13 weeks around the transition) may also provide insights, provided other explanatory variables have been statistically controlled for.

Several studies have empirically investigated the short-term and long-term impact of DST on road safety. However, these studies have taken place in different jurisdictions, and used a variety of statistical and methodological approaches. Given that a key argument currently being put forward for a move to CET is the potential road safety benefit, there is a need for these studies to be systematically synthesised. Such a synthesis would allow us to extrapolate key lessons from the literature base, to address over-reliance on individual studies and to overcome any tendency to selectively attend to evidence that supports a particular position relating to shifting time zones. This paper summarises the findings of the first systematic review of the literature relating to the impact of DST on road safety. The paper was drafted with reference to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (see online supplementary file PRISMA_2009_checklist)

The review addressed the following research questions:

What is the impact of DST on road traffic collisions, injuries and fatalities on morning versus evening risk?

What is the impact of DST on different types of road users (eg, vehicle occupants vs pedestrians, cyclists, etc)?

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted a systematic review of the literature pertaining to the impact of DST on road safety outcomes. Studies reporting a quantitative analysis, using primary data, of the effect of DST on road safety-related outcomes (ie, road traffic collisions, injuries and fatalities) were included in the review. Only studies published in English were included in the final review. We excluded qualitative studies, opinion pieces and newspaper/magazine articles, where no primary data were analysed. Studies were also excluded if they artificially constructed a change in lighting conditions (eg, in a laboratory experiment), if potential effects of DST were discussed but not controlled for in the analysis (eg, if studies drew conclusions about DST based on their findings but did not specifically examine DST transitions in their analyses), if the analysis did not specifically focus on the impact of DST and/or if the analysis related to time-zone changes and not DST. Studies involving all populations (ie, all types of road users) were included.

Papers were identified by conducting computerised searches of the Cochrane, EBSCO, Google Scholar, PsycInfo, PubMed, SafetyLit, Science Direct, Scopus, Web of Science, TRID, Lilacs and Scielo databases. We also searched ProQuest for ‘grey’ literature. Keywords informed by pilot scoping exercises, included daylight saving, DST, time change, road safety, road traffic collision, crash, accident, fatalities and injuries (eg, ['daylight saving*' OR DST OR 'time change'] AND ['road safety' OR 'road traffic' OR collision OR crash OR accident]), see online supplementary file 1 for the full search strategy for one database. The last search of these databases was performed on 18 January 2017. A request for papers was also sent to the International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group. Representatives from more than 30 road safety agencies worldwide, as well as academic institutions and members of the automobile industry, are members of the group. The review questions and search methodology were devised following consultation with the Road Safety Authority of Ireland, as a core user of road safety research. Collision victims, their families and other road safety stakeholders were not invited to contribute to the design or execution of the study.

bmjopen-2016-014319supp001.pdf (203.2KB, pdf)

Data collection and analysis

One reviewer reviewed titles and abstracts of all returned papers to identify potentially relevant studies, and reliability with a second reviewer (who reviewed 15% of these) was high (kappa=0.8). Discrepancies were resolved through discussions between the reviewers. On the basis of the abstract, full texts were retrieved for all studies that (i) met the inclusion criteria or (ii) did not provide enough information in the abstract to determine eligibility. One reviewer reviewed all full texts to determine eligibility for inclusion and this was checked, for 15% of studies, by a second reviewer (kappa=1.00). Where multiple papers referred to the same analysis on the same dataset, these were included in the review as one study only.

Data extraction was conducted by two reviewers using a standardised form. The following data was extracted from studies: location, year(s) captured, timeframe captured, source of road safety data used, research question(s), variable(s) included in analysis, outcome(s), findings, whether the analyses related to short- term or long-term impact, type of statistical analyses used and whether or not the analyses were broken down by (i) road user, (ii) time of day (ie, morning vs evening) and (iii) time of year (ie, spring DST change vs autumn DST change). We extracted data relating to short-term and long-term impact separately, where available. Examining short-term changes in collisions following DST transitions is thought to control for factors, such as traffic volume, that can vary over longer periods of time. We also extracted information relating to spring and autumn transitions separately, where available, in part because the spring transition leads to a shortening of the transition day by 1 hour, which can impact on sleep duration and latency.12 13 The autumn transition, conversely, adds an extra hour to the transition day and short-term collision trends are less likely to be linked to sleep duration and latency.

It is important to note that we attempted to extract information that would provide an estimate of the size of the collision datasets used in the papers. However, this proved extremely difficult as this information was often not explicitly provided by the authors; in some cases, we were left to derive estimates from graphical representations rather than tabular data. To compound this issue, where incidence was reported, varying units of measurement (eg, weeks, days, parts of days, etc) were often used, which could not reliably be reconciled into a standard reporting unit.

Data were synthesised using narrative synthesis.14 An initial scoping of the literature-base suggested that studies used a range of statistical approaches, and made varying statistical assumptions, and as such we did not seek to combine the findings through meta-analysis to estimate overall effect sizes.

Quality assessment

The quality of the papers included in the review was assessed using a bespoke set of quality assessment criteria.15 These criteria were identified by the research team to capture the extent to which the information provided answered the review questions. As such, the quality assessment is not an assessment of the strengths and limitations of the papers per se, but rather the extent to which they can inform current deliberations on the potential road safety value of changing time zones. The ‘ideal’ paper, in terms of the review questions, would a) use an official road safety database (eg, maintained by a statutory agency), b) report both short-term and long-term analyses, c) examine morning and evening trends, d) explore both spring and autumn transitions, e) probe the impact of light transitions on a range of road users (eg, pedestrians, cyclists, vehicle occupants, adults, children, etc), f) report statistics that could facilitate a meta-analysis, g) report data on factors, such as traffic volume, which could explain (in whole or part) any trends that emerged, and h) focus specifically on the impact of light (rather than sleep) on road safety. Each study was assessed based on these criteria, and coded as ‘met criterion’, ‘did not meet the criterion’ or ‘unclear’. To make these assessments, first, five papers were randomly selected and reviewed by two researchers (RC and KS) independently. As their inter-rater reliability was >95%, the remaining papers were quality-assessed by one researcher (ie, each coder coded 9–10 papers).

Results

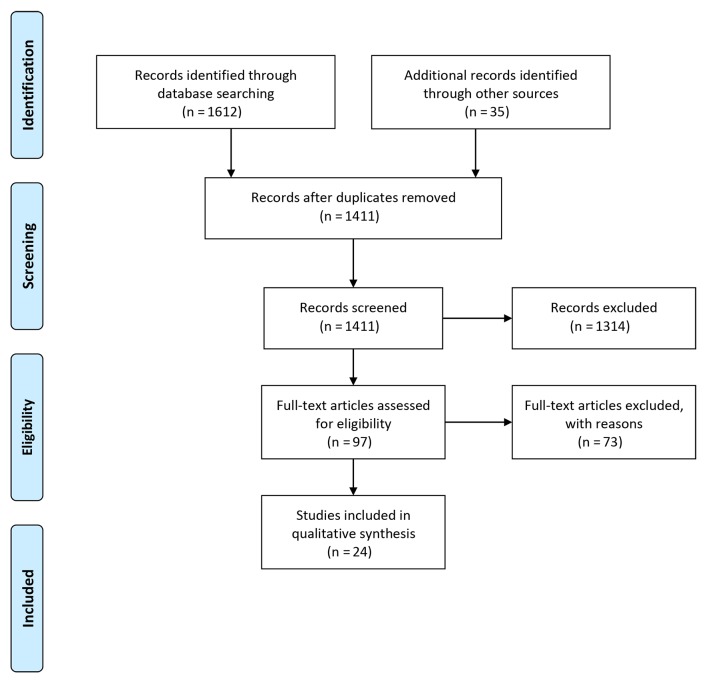

The search led to the identification of 1411 non-duplicate papers, 1314 of which were excluded based on title/abstract screening (see figure 1). Full-text reviews were conducted on 97 papers, 24 of which met the study inclusion criteria. There were eight papers published in a language other than English, on which abstract and/or full-text review could not be performed; these were excluded from the review in-line with the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Tables 1 and 2 provide summary information on the 24 studies included in the review.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart outlining selection of studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of papers included: short-term timeframe

| Author (year) | Country | Years | Focus (sleep/light) | By season | By time of day (morning/evening) | Population and outcome | Timeframe | Finding (narrative) |

| Askenasey26 (1997) | Israel | 1994–1996 | Sleep | ✓ | X | All collisions | 2 weeks before and 2 weeks after | Spring: technically a significant increase in RTCs after change to DST— however, 'within the chain of day-to-day increases the alleged effect of DST became non-significant' Autumn: significant decrease in RTCs after change back to ST (attributed to sleep benefits) |

| Conte27 (2007) | USA | 1987–2006 | Sleep | ✓ | X | All collisions excluding pedestrians | 2 weeks before and 2 weeks after | Significant differences in mean daily RTCs between DST adjusted and DST unadjusted Mondays (DST ‘seems to increase the number of traffic accidents’) Note: distinction between spring and autumn not clear from inferential statistics reported |

| Coren28 (1996) | Canada | 1991–1992 | Sleep | ✓ | X | All collisions | 1 week before, week of and 1 week after | Spring: the spring DST shift resulted in an average increase in RTCs of approximately 8% Autumn: the autumn shift resulted in a decrease in RTCs of approximately the same magnitude |

| Crawley29 (2012) | USA | 1976–2010 | Sleep and light | ✓ | X | All collisions | Monday before and after | Spring and autumn: no statistically significant short-term effects of DST |

| Green30 (1980) | UK | 1975–1977 | Light | ✓ | Evening only | All collisions | 5 days before and after and 10 days before and after | Spring: based on 5-day comparison, reduction of 31% in RTCs in March Autumn: increase of 64% in October. Less marked findings for 10-day data |

| Hicks31 (1983) | USA | 1976–1978 | Sleep | ✓ | X | All collisions | 1 week before and 1 week after | Spring and autumn: regardless of season, DST change was associated with a significant increase in RTCs during the postchange weeks |

| Hicks25 (1998) | USA | 1989–1992 | Sleep | ✓* | X | All alcohol-related fatal road traffic collisions | 1 week before and 1 week after | Spring and autumn: alcohol-related fatalities increased significantly in the first week after the DST transition, although this returned to baseline by the second week Note: spring and autumn combined as not statistically significantly different |

| Huang16 (2010) | USA | 2001–2007 | Sleep and light | ✓ | ✓ | All collisions and fatal collisions | First day (Sunday) of time change compared with other Sundays | Spring: short-term effect is not statistically significant Autumn: short-term effect is not statistically significant |

| Lahti32 (2010) | Finland | 1981–2006 | Sleep | ✓ | X | All collisions | 1 week before and 1 week after | Spring and autumn: transitions into and out of DST did not significantly increase the amount of traffic collisions |

| Lambe33 (2000) | Sweden | 1984–1995 | Sleep | ✓ | X | All collisions | Monday before and after, and 1 week after | Spring and autumn: the shift to and from DST did not have measurable effects on RTC incidence |

| Meyerhoff17 (1978) | USA | 1973–1974 | Light | ✓ | ✓ | All fatal collisions | Morning and evening on day of transitions in 1974 (DST) and 1973 (No DST) | Spring and autumn: DST reduced fatal RTCs by approximately 1% during several weeks at spring and autumn transitions. This effect was attributed to the spring transition, with little change during the autumn transition |

| Sarma & Carey20 (2016) | Ireland | 2003–2012 | Light | ✓ | ✓ Morning, evening, combined morning and evening, full day |

Collisions, injuries, fatalities for different road users (pedestrians, cyclists and all road users) | 1 and 2 weeks before and after transition into and out of DST | Spring: no change in collisions. Increase in casualties in the mornings in 2-week comparisons (33.5%) and increase in pedestrian casualties (105.3%) Autumn: decrease in collisions in the morning period at 1-week (26.9% decrease) and 2-week (17.3% decrease) comparisons. Evening pedestrian casualties increased in both sets of analyses (68% higher at 1 week and 32.5% over 2 weeks) |

| Smith34 (2014) | USA | 2002–2011 | Sleep and light | ✓ | ✓ | All fatal collisions | Unclear | Spring: 5.4%–7% increase in fatal RTCs immediately following spring transition. Autumn: no impact in autumn |

| Sood and Ghosh22 (2007) | USA | 1976–2003 | Sleep and light | Spring only | X | Fatal collisions: pedestrians and motor vehicle occupants | Monday before, Monday of and Monday after | Spring: no short-term effect, having controlled for collision trends within and across years |

| Stevens35 (2006) | USA | 1998–2000 | Light | ✓ | ✓ | Fatal and non-fatal collisions involving pedestrians and motor vehicle occupants | Five working days before & after | Spring and autumn: the immediate impact of DST, both spring and autumn, is negative, but is particularly marked for the autumn transition. An increase in daylight results in a decrease in the number of pedestrian crashes |

| Varughese36 (2001) | USA | 1975–1995 | Sleep | ✓ | X | All fatal collisions | Saturday/Sunday and Monday of the transition vs same days for the week before and after | Spring: there was a small significant increase in fatal RTCs on Monday from 78.2 to 83.5 (no impact on Saturday or Sunday). Autumn: there was a significant increase found in fatalities for Sunday from 126.4 to 139.5 (no difference for Saturday or Monday) |

| Whittaker19 (1996) | UK | 1983–1993 | Light | ✓ | ✓ | Casualties: vehicle occupants, cyclists, pedestrians, children | 1 week before and 1 week after | Overall net reduction in casualty numbers for BST periods compared with GMT. Spring: onset of BST in spring associated with reductions in casualty numbers of 6% in morning and 11% in evening. No rise in casualties with the darker mornings. Reductions were maximal in the pedestrian (36%), cyclist (11%) and schoolchild (24%) subgroups Autumn: the change back to GMT in autumn produced an anticipated reduction (6%) in casualties in the lighter mornings. Darker evenings associated with significant increases in casualties (4%), mainly vehicle (5%) and pedestrian (8%) |

*Spring and autumn transition data were combined as not statistically different from one another.

BST, British Standard Time; DST, daylight saving time; GMT, Greenwich Mean Time; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 2.

Characteristics of papers included: long-term timeframe

| Author (year) | Country | Years | Focus (sleep/light) | By season | By time of day (morning/ evening) | Population/ outcome |

Timeframe | Finding (narrative) |

| Chu37 (1976) | USA | 1974 | Light | January to March only | ✓ | All fatalities | 3 months | Overall estimate of 47 fatalities saved (8%) in the first half of 1974 that can be attributed to DST. A sharply higher fatality rate during morning rush hour and a sharply lower rate in the afternoon peak hour |

| Coate18 (2004) | USA | 1998 and 1999 | Light | ✓ | ✓ | Fatalities: pedestrians and motor vehicle occupants | 1 month before and 1 month after | Full-year DST would reduce pedestrian fatalities by 171 per year (13%), and motor vehicle occupant fatalities by 195 per year (3%). An hour later sunset would reduce evening pedestrian fatalities by about one-quarter and an hour later sunrise would increase morning fatalities by about one-third. No increased risk to school children from full-year DST |

| Crawley29 (2012) | USA | 1976–2010 | Both sleep and light | ✓ | X | All collisions | 13 weeks before and 9 weeks after. Also comparison of 1987–2003 to 1976–1986 | Significant fatal crash-saving effects of DST in the long run, shown particularly in the autumn test. ‘The spring test gave little evidence either way’ |

| Ferguson et al 9 (1995) | USA | 1987–1991 | Light | ✓ | ✓ | Fatal collisions: pedestrians and motor vehicle occupants | 13 weeks before and 9 weeks after | The most notable effects of changing light levels on fatal crashes were seen when light levels changed from light to twilight (collisions increased) and when twilight changed to light (collisions decreased). Benefits are smallest during the darkest winter months because the evening reduction is increasingly offset by increases during the morning. An estimated 901 fewer fatal crashes (727 involving pedestrians and 174 involving vehicle occupants) might have occurred had DST been retained year-round from 1987 to 1991 |

| Huang16 (2010) | USA | 2001–2007 | Both sleep and light | ✓ | ✓ | All collisions and fatal collisions | 8 weeks before and after | DST, all else equal, is associated with fewer RTCs and fatal RTCs for most day parts (except 09:00–-15:00 hours) |

| Meyerhoff17 (1978) | USA | 1973–1974 | Light | ✓ | ✓ | All fatal collisions | January–February and March–April 1974 (DST) and January–February and March–April 1973 (no DST) (long-term) | A net reduction of about 0.7% during the DST period, March and April 1974, compared with the non-DST period. March and April 1973, but little net DST effect on fatal accidents in winter. A marked decrease in evening fatalities is observed, but the morning increase is not seen as anticipated |

| Sarma and Carey20 (2016) | Ireland | Light | ✓ | ✓ | Collisions, injuries, fatalities for different road users (pedestrians, cyclists and all road users) | 5 and 7 weeks pretransition and post-transition into and out of DST | Transition into DST: increase in collisions in evening period for 5-week (12.6%) and 7-week (13.1%) analyses. Also increase in casualties in evening period at 5 (17.6% increase) and 7 weeks (19.5% increase). Overall (combining morning and evening peak periods) increase in casualties at 5-week (10.5% increase) and 7-week (12.7%) analyses. Transition out of DST: increase in morning casualties at 7 weeks (12.4% increase) and overall increase in casualties when morning and evening combined for 7 weeks (5.5% increase) |

|

| Sood and Ghosh22 (2007) | USA | 1976–2003 | Sleep and light | Spring only | X | Fatal collisions: pedestrians and motor vehicle occupants | 13 weeks before and 8 weeks after | Long-term reduction of 8%–11% in RTCs involving pedestrians, and 6%–10% in RTCs involving vehicle occupants |

| Sullivan21 (2001) | USA | 1987–1997 | Light | ✓ | Evening only | Fatal collisions: pedestrians and motor vehicles | 3 weeks before and after | Pedestrian fatalities 4.14 times more likely in darkness (DST) than in daylight (ST). Interaction between light and alcohol use |

| Sullivan38 (2002) | USA | 1987–1997 | Light | ✓ | ✓ | Fatal collisions: pedestrians and motor vehicle occupants | 9 weeks before and after | Overall, pedestrian fatalities 3–6.75 times more likely in darkness (ST) than in daylight (DST), while other crashes were only marginally more likely in darkness. Spring am: twilight shows a decline in crashes from week 8 (39 crashes) to week 1 (8 crashes); at the changeover, when the period is returned to darkness, the crash level rises again. Spring pm: the crash frequency is high during the dark period just before the DST changeover, and drops to 54, the week after the changeover and declines more the following week to 32. Autumn am: 79 crashes before the transition and 29 after. Autumn pm: in the week before the transition there were 65 crashes, in the following week there were 227, an increase of three and a half times |

| Sullivan39 (2003 and 2004) | USA | 1987–2001 | Light | Autumn only | Evening only | Fatal collisions: motor vehicle occupants only | 5 weeks before and after | Rear-end collisions change from an average count of about 13 crashes in the light (DST) to an average of 37 in the dark (ST). Impact of light on crash risk varies across rear-end collision types |

| Sullivan6 (2007) | USA | FARS=1987–2004; NCDOT=1991–1999 | Light | ✓ | Evening only | Fatal and non-fatal collisions: pedestrian (child, adult, elderly) and motor vehicle occupants | 5 weeks before and after | Fatal crashes involving pedestrians, animals and other motor vehicles showed the most reliable increases in risk in low light levels (ST). Children show a reliably greater risk in darkness, but this risk is much smaller than the risk observed for adult and elderly pedestrians, which is nearly seven times greater in darkness. Even when the data are not separated by age, the apparent increase in pedestrian risk in the dark is very strong |

DST, daylight saving time; RCT, randomised controlled trial; ST, standard time.

Data for 17 studies (71%) were from the USA, with 8% (n=2) of studies based on DST in the UK. Other countries included were Canada, Finland, Israel, Ireland and Sweden (21% of studies). Years captured in the analyses ranged from 1973 to 2012.

Seventeen of the included studies (71%) investigated the short-term effects of DST by examining the period immediately (2 weeks or less) before and after the DST shift. Of these papers, eight (47%) focused on the effects of sleep disruptions caused by the DST shift (see 'What is the impact of DST on road traffic collisions, injuries and fatalities?' section for more detail), five (29%) focused on light levels and four (24%) looked at both sleep and light (see table 1). Twelve of the studies (50%) examined the overall or long-term effects of DST, focusing on changes in light levels that result from DST. Timeframes captured in these studies ranged from 3 to 13 weeks around the DST transitions (see table 2). Five studies examined both short-term and long-term effects, and these analyses were treated separately in the synthesis.

Six of the short-term analyses (35%) distinguished between morning and evening risk, while seven (58%) of the long-term analyses did so. Almost all (94%, n=16) of the short-term analyses separated spring from autumn DST transitions, while 75% (n=9) of the long-term studies made this distinction. Nine of the 24 studies (38%) provided analyses by road user (eg, pedestrian vs motor vehicle user).

What is the impact of DST on road traffic collisions, injuries and fatalities?

Short-term impact

For the transition into DST (ie, the spring shift), findings were inconsistent across studies. Sixteen of the short-term studies provided relevant statistical data. Three of these studies (19%) reported a reduction in collisions, six (38%) reported an increase in collisions and seven (44%) reported no change. Increases were largely attributed to sleep disruption (latency and duration), in line with previous research.12 13

An examination of the short-term change in road traffic collisions around the transition back to ST in autumn may offer a purer test of the impact of DST on road safety. This transition results in improved lighting in the morning, but a reduction in the evening, which should lead to an increase in road traffic collisions. Since this transition does not lead to a ‘missing hour’, sleep effects should be less pronounced. Fifteen of the short-term studies provided relevant data. Again, findings were inconsistent across studies, with five studies (33%) reporting a decrease in collisions, five studies reporting an increase and five studies reporting no change.

It is worth noting that a majority of these short-term studies focused on the effects of sleep deprivation on road traffic collisions, particularly during the spring transition, rather than considering the potential impact of a permanent shift in time zones on road safety outcomes.

Long-term impact

Twelve of the 24 studies examined the long-term impact (>2 weeks) of DST on road safety outcomes. These studies reported a reduction in collisions, injuries and fatalities associated with DST. The exception was the analyses of trends in Ireland, which reported increases in collisions and casualties in some of the analyses. For those that did report reductions, the overall magnitude of this effect, although hard to estimate given the variability in study approaches and analyses, tended to be small. Huang and Levinson16 for example, reported that ‘a day in DST, all else equal, is associated with about 0.09% fewer crashes than a day in ST (standard time)’ [p.519]. Meyerhoff reported a net reduction of 0.7% of fatal collisions during 2 months in DST, compared with 2 months in ST, and little overall impact of DST in winter months.17

Importantly, there was an observed increase in collisions during the morning hours in DST (although not in all studies; see17), but it was noted that the overall benefit to road safety tended to outweigh the morning risks. Several studies extrapolated from the findings of their analyses to the impact of retaining DST year-round.

What is the impact of DST on road traffic collisions, injuries and fatalities for different types of road users (eg, vehicle occupants vs pedestrians, cyclists, etc)?

Of the nine studies that analysed DST effects on different types of road users, the beneficial effects of DST were most pronounced for pedestrians and cyclists. In one study, the estimated effects of retaining DST approximated 13% fewer pedestrian fatalities and 3% fewer vehicle occupant fatalities.18 The collision risk posed to pedestrians following the transition back to ST was found to be greater than that for motor vehicle occupants. Ferguson et al, for example, reported a greater collision risk for pedestrians than for motor vehicle occupants following the transition from DST to ST. Specifically, they found the change from daylight to twilight to be associated with a 300% increase in fatal collisions involving pedestrians. Of the 901 fewer fatal collisions they estimate would have occurred from 1987 to 1991, had DST operated year-round, 727 of these would have involved pedestrians, while 174 would have involved motor vehicle occupants.9 Whittaker19 reported that the onset of DST in spring was associated with a reduction in casualties that was particularly pronounced for pedestrians (36%) and cyclists (11%). Sarma and Carey20 found a significant reduction in cyclist casualties following the autumn transition, although the authors noted that the darker evenings may have led to reductions in bicycle use, which would have impacted on total incidence.

Sullivan and Flannagan found 4.1 times as many pedestrian fatalities in darkness (during ST) compared with daylight (during DST), and 1.3 times as many motor vehicle collisions in darkness, compared with daylight. Thus, although darkness increased collision risk for both groups of road users, the risks posed were greatest for pedestrians.21 Sood and Ghosh reported an overall long-term reduction in collisions involving both pedestrians (8% to 11%) and motor vehicle occupants (6% to 10%). They noted that the ‘saving’ in collisions peaked in the third (for pedestrians) and fourth (for motor vehicle occupants) weeks after DST onset.22

Again, however, it is important to note that the impact of DST on pedestrian risk may differ from morning to evening. Coate and Markowitz estimated that year-round DST would reduce pedestrian fatalities in the evening by one-quarter, but increase those in the morning by one-third. They conclude that, since pedestrian activity is higher in the evening compared with the morning, year-round DST would reduce overall pedestrian fatalities by 13%.18

Quality assessment

Table 3 summarises our assessment of the value the studies included in the review provided, based on the extent to which each could inform the core review questions. With the exception of one paper, all studies had access to data gathered through some form of mandatory reporting system (eg, national road safety database). Ideally, papers would report analyses for the spring and autumn transitions, and capture both short- and long-term impact of DST, for morning and evening periods. It was typical for most of the papers to report separate analyses for spring and autumn (21 papers did so).

Table 3.

Summary results of quality assessment

| Author (year) | Data source | Sampling | Statistical reporting | Focus | ||||

| Official* | Short and long term† | Morning and evening‡ | Spring and autumn§ | Multiple road users¶ | Incidence/ mean/SD** | Other factors†† | Light rather than sleep‡‡ | |

| Askenasy26 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| Chu37 | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Coate18 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Conte27 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Coren28 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| Crawley29 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y |

| Ferguson9 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Green30 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Hicks25 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Hicks31 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| Huang16 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| Lahti32 | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N |

| Lambe33 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| Meyerhoff17 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Sarma and Carey20 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Smith34 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| Sood and Ghosh22 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Stevens (2005) | ? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Sullivan21 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sullivan38 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Sullivan (2003 and 2004) | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Sullivan6 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Varughese36 | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| Whitaker (1996) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

*Data derived from official collision data source such as police or national authority.

†Short-term and long-term analyses reported.

‡Separate analyses for morning and evening collisions is more sensitive to DST effects.

§Separate analyses for spring and autumn transitions can test hypothesised DST effects for each transition.

¶Separate analyses for different road users is important to the CET debate.

**Reporting of incidence and mean/SD would support a meta-analytic review if comparison periods were uniform across studies.

††Reporting data for factors that could explain, in whole or part, collision trends around DST transitions aids interpretation of light effects.

‡‡Papers that focused specifically on light transitions, rather than only on the impact of time changes on sleep duration and latency, were more relevant to our review (if they focused on both sleep and light, they were coded Y).

CET, Central European Time; DST. daylight saving time.

However, just five papers included both short-term and long-term analyses, and only half (12 papers) reported results for morning and evening periods. Similarly, most (15 papers) did not report data for different road users (eg, pedestrian and vehicle occupants) and did not consider other contributory factors for collision risk (15 papers), which would have facilitated the synthesis reported here. While most of the papers included incidence or mean/SD descriptive results (19 papers), there was considerable heterogeneity across studies in terms of the time periods around the DST transitions selected for the analyses (see tables 1 and 2 for details); this rendered the data as a whole difficult to subject to meta-analysis.

Discussion

Summary findings

The core objective of this review has been to contribute to the evidence base that can inform the current debate on the potential road safety benefit of a time-zone change that would result in brighter evenings. The most valid evidence from the DST literature is that pertaining to the short-term impact of shifting to, and from, DST. These analyses should allow us to isolate the ‘light’ effect, given that there should be minimal changes in extraneous factors. Findings from these studies were inconsistent, with results suggesting that shifting light by adjusting time can have positive or negative road safety consequences, or result in no change. In addition, most studies did not extrapolate findings to hypothetical conditions under a more permanent change in time. Thus, the short-term evidence cannot support or refute the assertion that a move to CET will have a road safety benefit in the UK and Ireland.

The long-term findings were more consistent, and the overall impact of DST was positive (ie, risk-reducing) in a majority of studies included. The difficulty here, however, is twofold. First, this reduction cannot be attributed solely to DST, as a variety of risk factors for road collisions vary in the long-term, including traffic flow and weather conditions. Second, with the exception of the analyses from Ireland, all studies were conducted in the USA, undermining the predictive validity of the findings when applied to other jurisdictions. In summary, the review reports inconsistent findings for the short-term impact of DST, and questions the validity of the long-term analyses.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations associated with this review. First, the DST literature reviewed does not provide a test of the impact of a permanent time-zone shift on road safety. DST, which involves a temporary shift of light between morning and evening, is distinct from a time-zone change, which would involve a permanent shift of 1 hour, and then an additional 1 hour shift during DST. However, in the absence of road safety data from jurisdictions that have gone through a permanent time-zone shift, the DST literature is an important and relevant source of evidence that is often referenced in these debates.

Second, the review excluded a small number of papers that examined collisions before, during and after the BST experiment that occurred between 1968 and 1971. Apart from not meeting our inclusion criteria (ie, they did not examine DST), these papers, we would argue, lack validity in terms of contemporary road safety policy-making given the dramatic changes in traffic volume, road infrastructure, vehicle engineering and driver behaviour that have occurred over the last 40 years. We acknowledge, however, that others who have considered the road safety evidence from the BST experiment have estimated that a permanent move to CET would have potential savings for pedestrians and vehicle occupants (as reported in the 'Introduction' section).

Third, the review is limited by the heterogeneous nature of the literature base. This includes variation in time sampling, statistical analyses and populations of interest. One consequence of this heterogeneity is that we were unable to complete a meta-analysis of the studies. For example, the papers report findings based on differing time periods before and after DST (eg, timeframes among short-term studies varied from 1 day to 2 weeks around the transitions). It is very difficult to reconcile this heterogeneity of comparisons into meaningful mean or dispersion effects during meta-analysis (for more details see refs 23 and 24).

The review is also limited by the methodological and statistical limitations of the individual studies. In particular, individual studies tended not to attempt to isolate light effects by statistically controlling for other potential explanatory variables, such as traffic volume, for example, or holiday periods. The absence of reporting of the incidence rates behind the analyses in the papers is a further limitation, although it is worth nothing that the long-term analyses were characterised by large datasets of collisions and samples only became small where analyses involved subsets of data for short-term effects and involving specific types of collisions (eg, in Hicks et al 25 review of alcohol-related fatalities the incidence fell below 50 fatalities when examining fatalities across time periods during the day).

Finally, the research team decided to double screen 15% of papers when isolating papers that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria, rather than double-screening all papers. The original review protocol proposed that double screening would continue up until high intercoder reliability was reached; in practice, this was achieved after 15% of papers were screened.

Conclusions and implications

In summary, the picture emerging from this review is complex. We found that the short-term effects of DST are likely to be small and potentially negative or positive depending on time of year and day. The long-term effects tend to be positive, but may be attributable to factors other than light. Future research needs to take into consideration these factors where possible.

The DST literature, taken as a body of research, should not be used to support or refute the assertion that shifts in time-zones can have a road safety benefit. Inconsistent findings and conclusions across studies, combined with the heterogeneous nature of the studies, mean that DST could possibly have a positive or negative impact on collisions, but may also have no effect. For the UK and Ireland, where a move to CET is being debated, arguments may be on a stronger foundation where they focus on the economic value (or not) of such a change rather than the potential impact on road safety.

bmjopen-2016-014319supp002.doc (69.5KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KS conceived the systematic review and supervised the research. RC was primarily responsible for database searching and reviewing texts for inclusion. KS and RC both contributed to the data extraction, data analysis and manuscript drafting.

Disclaimer: This paper is based on a report commissioned by the Road Safety Authority of Ireland. The views reported here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Road Safety Authority.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Schiavenza M. China only has one time Zone—and That's a Problem. Secondary China Only Has One Time Zone—and That's a Problem. 2013. http://www.theatlantic.com/china/archive/2013/11/china-only-has-one-time-zone-and-thats-a-problem/281136/.

- 2. BBC. Russian clocks go back for last time. secondary russian clocks go back for last time. 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-29773559.

- 3. BBC. North Korea's new time zone to break from 'imperialism'. Secondary North Korea's new time zone to break from 'imperialism'. 2015. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-33815049.

- 4. Tadeo M. Breaking with Old Politics May Begin with clock Change in Spain. secondary breaking with Old Politics May Begin with clock Change in Spain. 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-25/breaking-with-old-politics-may-begin-with-clock-change-in-spain.

- 5. ROSPA. Single double british Summertime Factsheet. 2014.

- 6. Sullivan JM, Flannagan MJ. Determining the potential safety benefit of improved lighting in three pedestrian crash scenarios. Accid Anal Prev 2007;39 47:638–47. 10.1016/j.aap.2006.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Broughton J, Stone M. A new assessment of the likely effects on road accidents of adopting SDST: Transport Research Laboratory, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adams J, White M, Heywood P. Year-round daylight saving and serious or fatal road traffic injuries in children in the north-east of England. J Public Health 2005;27:316–7. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferguson SA, Preusser DF, Lund AK, et al. . Daylight saving time and motor vehicle crashes: the reduction in pedestrian and vehicle occupant fatalities. Am J Public Health 1995;85:92–5. 10.2105/AJPH.85.1.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Plainis S, Murray IJ, Pallikaris IG. Road traffic casualties: understanding the night-time death toll. Inj Prev 2006;12:125–38. 10.1136/ip.2005.011056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harrison Y. The impact of daylight saving time on sleep and related behaviours. Sleep Med Rev 2013;17:285–92. 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lahti TA, Leppämäki S, Lönnqvist J, et al. . Transitions into and out of daylight saving time compromise sleep and the rest-activity cycles. BMC Physiol 2008;8:3 10.1186/1472-6793-8-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kantermann T, Juda M, Merrow M, et al. . The human circadian clock's seasonal adjustment is disrupted by daylight saving time. Curr Biol 2007;17:1996–2000. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. . Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC methods programme 2006;15:047–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang A, Levinson D. The effects of daylight saving time on vehicle crashes in Minnesota. J Safety Res 2010;41 20:513–20. 10.1016/j.jsr.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meyerhoff NJ. The influence of daylight saving time on motor vehicle fatal traffic accidents. Accident Analysis & Prevention 1978;10:207–21. 10.1016/0001-4575(78)90012-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coate D, Markowitz S. The effects of daylight and daylight saving time on US pedestrian fatalities and motor vehicle occupant fatalities. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2004;36 57:351–7. 10.1016/S0001-4575(03)00015-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whittaker JD. An investigation into the effects of British Summer Time on road traffic accident casualties in Cheshire. J Accid Emerg Med 1996;13:189–92. 10.1136/emj.13.3.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sarma KM, Carey RN. The potential impact of the implementation of the Brighter Evenings Bill on road safety in the Republic of Ireland. A report for the Road Safety Authority of Ireland. 2015.

- 21. Sullivan JM, Flannagan M. Characteristics of pedestrian risk in darkness, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sood N, Ghosh A. The short and long Run effects of Daylight Saving Time on Fatal Automobile Crashes. B E J Econom Anal Policy 2007;7 10.2202/1935-1682.1618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Green S, Higgins J. The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011 The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, et al. . Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, LTD, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25. HICKS GJ, W.DAVIS J, Hicks RA. Fatal alcohol-related traffic crashes increase subsequent to changes to and from daylight savings time. Percept Mot Skills 1998;86:879–82. 10.2466/pms.1998.86.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Askenasy JJ, Goldstein R, Askenasy N, et al. ; Some light on the controversy about the effects of the shift to daylight saving time on road accidents In: MeierEwert K, Okawa M, eds Sleep-Wake Disorders, 1997:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conte MN, Steigerwald DG. Do Daylight-Saving Time Adjustments Impact Human Performance? 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coren S. Daylight Savings Time and Traffic Accidents. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1996;334:924–5. 10.1056/NEJM199604043341416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crawley J. Testing for Robustness in the relationship between Fatal Automobile Crashes and Daylight Saving Time, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Green H. Some effects on accidents of changes in light conditions at the beginning and end of british summer time, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hicks RA, Lindseth K, Hawkins J. Daylight saving-time changes increase traffic accidents. Percept Mot Skills 1983;56:64–6. 10.2466/pms.1983.56.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lahti T, Nysten E, Haukka J, et al. . Daylight Saving Time Transitions and Road Traffic Accidents. J Environ Public Health 2010;2010:1–3. 10.1155/2010/657167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lambe M, Cummings P. The shift to and from daylight savings time and motor vehicle crashes. Accid Anal Prev 2000;32:609–11. 10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00088-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith AC. Spring forward at your own risk: daylight Saving Time and Fatal Vehicle Crashes, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stevens C, Lord D. Evaluating safety effects of Daylight Savings Time on Fatal and Nonfatal Injury Crashes in Texas. Transp Res Rec 2006;1953:147–55. 10.3141/1953-17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Varughese J, Allen RP. Fatal accidents following changes in daylight savings time: the American experience. Sleep Med 2001;2:31–6. 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chu BY-C, Nunn GE. An analysis of the decline in California traffic fatalities during the energy crisis. Accident Analysis & Prevention 1976;8:145–50. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sullivan JM, Flannagan MJ. The role of ambient light level in fatal crashes: inferences from daylight saving time transitions. Accid Anal Prev 2002;34:487–98. 10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00046-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sullivan JM. Visibility and rear-end collisions involving light vehicles and trucks. Michigan, USA: The University of Michigan, Transportation Research InstituteAnn Arbor, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014319supp001.pdf (203.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014319supp002.doc (69.5KB, doc)