Abstract

Objective

To determine the risk of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) following sPTB in singleton pregnancies.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis using random effects models.

Data sources

An electronic literature search was conducted in OVID Medline (1948–2017), Embase (1980–2017) and ClinicalTrials.gov (completed studies effective 2017), supplemented by hand-searching bibliographies of included studies, to find all studies with original data concerning recurrent sPTB.

Study eligibility criteria

Studies had to include women with at least one spontaneous preterm singleton live birth (<37 weeks) and at least one subsequent pregnancy resulting in a singleton live birth. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess study quality.

Results

Overall, 32 articles involving 55 197 women, met all inclusion criteria. Generally studies were well conducted and had a low risk of bias. The absolute risk of recurrent sPTB at <37 weeks’ gestation was 30% (95% CI 27% to 34%). The risk of recurrence due to preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) at <37 weeks gestation was 7% (95% CI 6% to 9%), while the risk of recurrence due to preterm labour (PTL) at <37 weeks gestation was 23% (95% CI 13% to 33%).

Conclusions

The risk of recurrent sPTB is high and is influenced by the underlying clinical pathway leading to the birth. This information is important for clinicians when discussing the recurrence risk of sPTB with their patients.

Keywords: preterm birth, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes, recurrence, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study strengths include the comprehensive search strategy with no language restrictions used in the nature of the systematic review.

Limitations primarily relate to the underlying data that was available on this topic. Most of the included studies were observational in nature. Additionally, many primary studies examining the recurrence risk of preterm birth had to be excluded as they did not clearly differentiate between spontaneous and indicated preterm delivery. There was a high degree of heterogeneity in the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) is defined as any live birth occurring before 37 completed weeks of gestation; this can be subdivided into extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28–<32 weeks), moderately preterm (32–<34 weeks) and late preterm (34–<37 weeks) birth based on the gestational age at delivery.1 This subcategorisation is important as gestational age is inversely associated with increased mortality, morbidity and the intensity of neonatal care required at birth.2 Worldwide, 11.1% of infants are born preterm every year.2 PTB is the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality and second most common cause of death, after pneumonia, in children under 5 years of age.3 4

Indicated preterm births (iPTB) are those induced for medical reasons, such a pre-eclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction or fetal distress. However, approximately 70% of PTB occur spontaneously.5 The clinical pathways that lead to spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) typically include preterm labour (PTL) and preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), although these occur on a spectrum and may co-occur in the same clinical setting. PTL is defined as regular contractions and cervical changes at less than 37 weeks gestation and PPROM is defined as spontaneous rupture of membranes at least 1 hour before contractions at less than 37 weeks gestation.5 Known risk factors for sPTB include a previous PTB, black race, low maternal body-mass index, comorbidities, a short cervical length and a raised fetal fibronectin concentration.5 6 Despite knowing these risk factors, our understanding of the aetiology behind sPTB is poor and sPTB is considered to be multifactorial in nature.6 7

Although sPTB has a tendency to recur, little is known about the recurrence risk.7 This is of concern because sPTB is a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality, and it also has a large economic burden.8 Further, women who have had a previous sPTB are likely to be anxious during their subsequent pregnancies, which itself can lead to sPTB and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.9–11 Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the absolute risk of recurrent sPTB following sPTB in singleton pregnancies. By better understanding the recurrence risk of sPTB, healthcare workers may be better equipped to manage patient's needs and anxieties, as well as develop and apply preventative treatments.

Methods

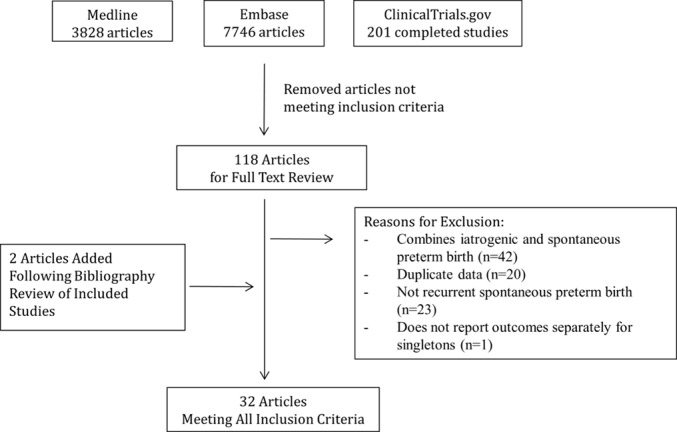

Two study authors (ZV and CH) executed a comprehensive literature search of Medline (from 1946 to 2015) and Embase (from 1980 to 2015) to identify publications that contained key terms related to recurrent sPTB in June 2015. The search was updated in July 2016 and expanded to included completed studies identified through ClinicalTrials.gov. The search was further updated in May 2017. PPROM, PTL and related terms were included in the search. For the full search strategy, please refer to online supplementary appendix A. Titles and abstracts of these articles were screened for relevance by two reviewers (ZV and CH) to determine which articles were to undergo full-text review. Articles identified by either reviewer at this stage as potentially relevant moved onto full text review. Two independent reviewers (ZV and CP) jointly assessed the final eligibility of the full-text reviewed articles. We resolved disagreements in full-text eligibility or data abstraction by involvement of a third party (AM). The bibliographies of included studies were reviewed to identify additional publications not found through the database search. A complete summary of the search strategy can be found in figure 1. No patients were directly involved in this study. As this study only used published data, it was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies.

bmjopen-2016-015402supp001.pdf (157.6KB, pdf)

All studies with original data concerning recurrent sPTB and n≥20 were considered for inclusion. No language restrictions were used. Conference abstracts were not considered. To be included, studies had to include women with at least one spontaneous preterm live birth (delivery <37 weeks of gestation) in their obstetric history and at least one subsequent pregnancy resulting in a live birth. Only studies looking at singleton pregnancies were included. Animal studies, studies that only included iPTB, studies that combined iPTB and sPTB, and studies on PPROM or PTL where it was not clear if it resulted in sPTB were excluded. In the case of duplicate data, the study with the largest sample size was included.

The data extraction were completed independently by ZV and CP using a standardised data extraction form. Data were reviewed by AM prior to analysis to ensure completeness. Information on the authors, title, publication year, data year, location of study, study design, definitions of PTB, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were all extracted. In addition, information was extracted on the number of women with sPTB in their initial pregnancy, whether due to PPROM or PTL, number of women with term births in subsequent pregnancies, and number of women with PTB in subsequent pregnancies, whether due to PPROM, PTL or indicated causes. For studies that reported on total reproductive history, only data on the first two consecutive pregnancies were extracted. Given the observational nature of this review, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale12 was used to assess study quality of both cohort studies and randomised controlled trials.

The primary outcome measured was the recurrence rate of sPTB at <37 weeks gestation. Secondary outcomes were recurrence rate of sPTB due to PPROM at <37 weeks (following sPTB due to PPROM in the index pregnancy), recurrence rate of sPTB due to PTL at <37 weeks (following sPTB due to PTL in the index pregnancy), the recurrence of sPTB by gestational age, and occurrence of iPTB at <37 weeks after a previous sPTB.

For our analysis, we reported the pooled risk of recurrent PTB and accompanying 95% CIs for sPTB <37 weeks gestation, by iPTB, by gestational age overall, and for PPROM and PTL. Stratified analysis was used to examine the recurrence rate of sPTB <37 weeks gestation by study design and quality. An a priori decision was made to use a random-effects model for all models in anticipation of clinical heterogeneity between studies. The metaprop command in Stata was used to conduct the analysis and exact CIs were reported.13 Forest plots were used to graphically represent the data. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using I2, the Cochrane Q statistic, and accompanying p values. All analyses were conducted using Stata SE V.14.

Results

The search returned 11 775 articles, of which 118 met criteria for full-text review (figure 1). Overall, 32 articles met all of the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.14–45 A summary of all of the study data can be found in online supplementary appendix B (recurrence risk of sPTB is located in table B1 and occurrence risk of iPTB following sPTB is located in table B2). The included studies were almost entirely cohort studies, with only five randomised controlled trials.22 26 28 35 40 The sample sizes in the studies ranged from 33 to 17 334 women and the rate of recurrent sPTB at <37 weeks gestation ranged from 15.4% to 85.5%. Many of the studies had different definitions of sPTB and therefore they could not be combined for meta-analysis. There were only a sufficient number of studies that defined PTB as occurring prior to 37 weeks in both the index and subsequent pregnancy to create pooled estimates.

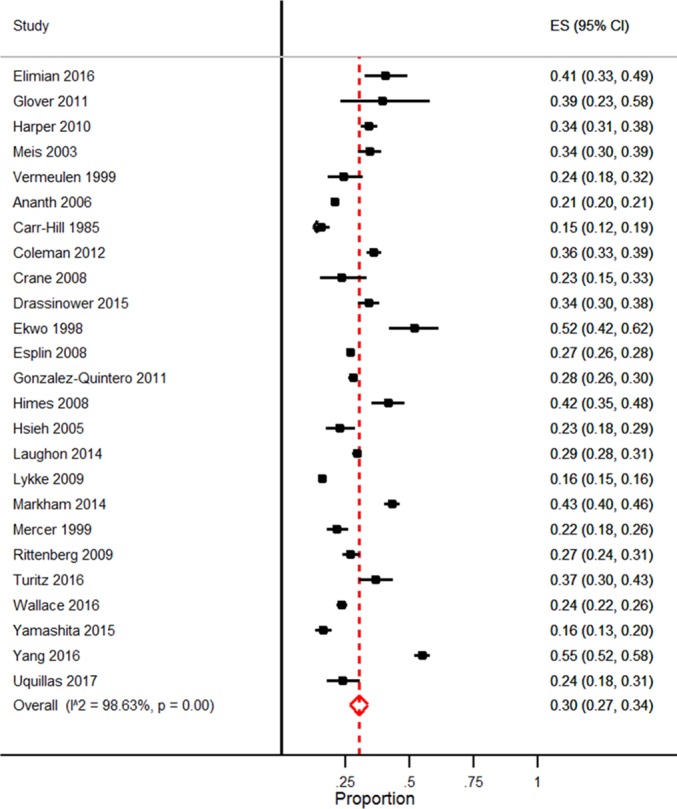

The overall risk of recurrent sPTB at <37 weeks gestation (n=25 studies, 52 070 women) was 30% (95% CI27% to 34%) with a significant Q (p=0.00) and I2 of 98.6%, indicating between-study heterogeneity (figure 2). The recurrence rate did not significantly differ between randomised controlled trials (34%, 95% CI 29% to 38%; n=5 studies, 1661 women) and cohort studies (29%, 95% CI 26% to 33%, n=20 studies, 50 409 women). The risk of iPTB at <37 weeks’ gestation after a previous sPTB (n=6 studies, 18 355 women) was 5% (95% CI 3% to 7%) with an I2 of 98.0%.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the rate of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth at <37 weeks’ gestation. ES, effect size.

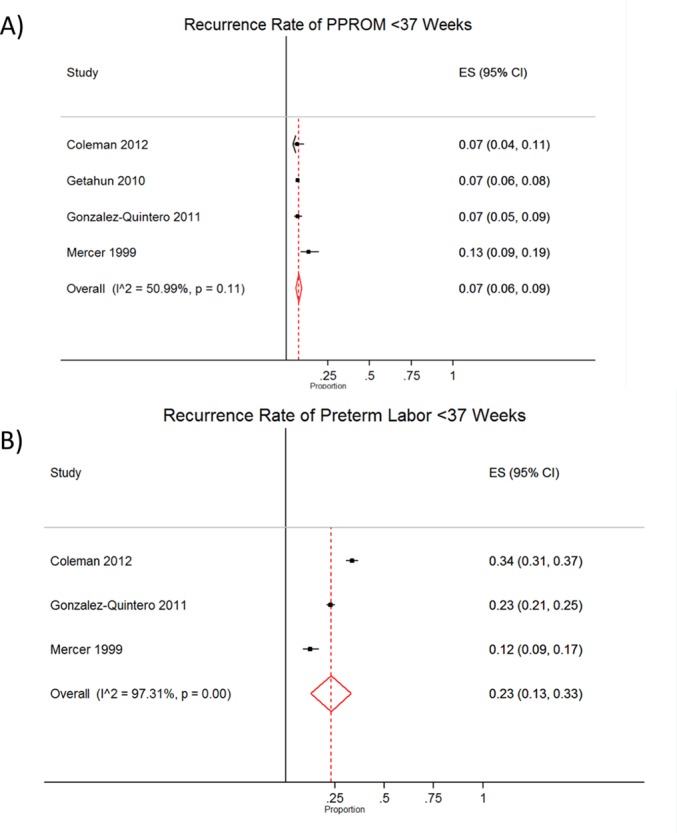

Few studies looked specifically at the recurrence of PPROM and PTL resulting in sPTB in singleton pregnancies following prior PPROM or PTL respectively. However, the identified risk of recurrent PPROM at <37 weeks gestation (n=4 studies, 3138 women) was 7% (95% CI 6% to 9%) with an I2 of 51% and the risk of recurrent PTL at <37 weeks’ gestation (n=3 studies, 2852 women) was 23% (95% CI 13% to 33%) with an I2 of 97.3% (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of the rate of (A) recurrent preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) and (B) recurrent preterm labour (PTL) at <37 weeks’ gestation. ES, effect size.

The majority of the studies were of high quality (see online supplementary appendix C). As this study exclusively examined the recurrence risk of sPTB, two elements of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale relating to the selection of the unexposed cohort and the comparability of the exposed and unexposed cohorts were unable to be assessed. Cohort studies typically traded off between being generalisable to the broader patient population not seen in a tertiary centre or having detailed clinical data available. All cohort studies had a quality score of four or five out of a possible six points. No statistically significant differences in the recurrence rate of sPTB prior to 37 weeks was observed based on quality score in cohort studies (Score 4: 27%, 95% CI 21% to 32%; Score 5: 31%, 95% CI 26% to 36%). All randomised controlled trials were deemed to be high quality (score 7/8).

Discussion

This meta-analysis provides an overview of the overall risk of recurrent sPTB. We found that the absolute risk of recurrent sPTB at less than 37 weeks gestation in pregnancies was 30%; this estimate was consistent across study designs and study quality. Interestingly, the risk of recurrent PTL was found to be 23%, similar to the overall risk of recurrent sPTB. Conversely, if a woman has a sPTB due to PPROM, she is less likely to have recurrent PPROM leading to sPTB, with a risk of only 7%. Thus, the clinical pathway that leads to sPTB appears to influence the risk of recurrence.

In a 2014 systematic review by Kazemier et al, they found that the risk of recurrence of PTB is influenced by the singleton/twin order in both pregnancies. When they looked at spontaneous preterm singleton births after a previous singleton pregnancy, they found that the risk of recurrence of sPTB was 20.2%.46 In contrast to ours, their search strategy was exceedingly complex and included only cohort studies. Ultimately, after abstract review they were left with only six studies that looked at singleton-singleton pregnancies, which could explain the difference in our recurrence risk. Further, our study is novel as we differentiated risk by clinical pathway leading to sPTB, whether PTL or PPROM. Ultimately, we found that while all sPTB tends to recur, the clinical pathway of the first sPTB is important in determining that recurrence risk. Previous studies tend to combine these underlying pathways together, but our results suggest that perhaps they should not be pooled. Some studies also suggest that children born following PPROM have increased mortality47–49 and worse health outcomes50 compared with children born after PTL, which further supports the premise that these should be looked at as separate clinical conditions.

However, new evidence suggests that PTB and the underlying pathologies that lead to PTB are not mutually exclusive; thus, sPTB and iPTB should perhaps not be considered completely separate phenomena. Basso and Wilcox estimated that mortality due to immaturity itself was about 51%, whereas underlying pathologies that led to PTB accounted for approximately half of mortality.51 Similarly, in a recent study by Brown et al, the authors found that gestational age is on the causal path between biological determinants of PTB and neonatal outcomes.52 Infants who were exposed to both pathological intrauterine conditions and early delivery had increased risk for poor neonatal outcomes. As such a pathological intrauterine environment, for instance, one characterised by infection, placental ischaemia and other biological determinants, acts through early delivery to produce poor outcomes. Ananth et al found that women with a sPTB were not only likely to experience recurrent sPTB, but they were also associated with increased risks of having a medically indicated PTB and vice versa.7 Prevention of preterm mortality requires more than the resolution of PTB, but must also address the underlying aetiologies.

Strengths of our systematic review and meta-analysis include our broad search strategy with no language restrictions, which resulted in a large sample size of pooled data. Limitations include the fact that most of the studies were observational cohort studies and thus prone to bias, and there was significant between-study heterogeneity. This is important as many women included in this body of literature would have been offered some form of therapy to reduce their risks of recurrent PTB. In a similar vein, we also included participants from both the treated and control arms of the included randomised controlled trials. With the exception of the trial lead by Meis et al, which found a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of sPTB in women treated with progesterone (RR=0.66, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.81),35 the other trials had null findings. Strategies to prevent PTB are varied and evidence of their effectiveness are mixed.53 Effective strategies to prevent PTB can be implemented at the individual level (ie, progesterone supplementation, cervical cerclage, smoking cessation), the clinic/hospital level (ie, hard-stop policies to prevent non-medically indicated late preterm and early term birth, PTB prevention clinics) and the societal level (ie, smoke-free legislation to reduce environmental tobacco smoke, legislation regarding single-embryo transfer during in vitro fertilisation).53 As documentation of specific treatment strategies was not consistently reported in this body of literature, we were not able to synthesise these results according to specific types of treatment. While both small and large studies were identified and included, publication bias cannot be entirely ruled out. While the decision to only include studies with a minimum sample size of 20 was used to exclude case studies of rare cases that may not be generalisable, this may have inadvertently resulted in the exclusion of some small case series. Additionally, we only searched three independent sources and reviewed the bibliographies of included articles; thus, articles in journals that were not indexed in either Medline or Embase or studies that were not registered on clinicaltrials.gov or were not cited by articles that were ultimately included in this review would not have been identified. We anticipate that the impact of this would be minimal as a study examining the effectiveness of different databases to identify studies related to maternal morbidity and mortality concluded that Medline and Embase has the highest yield in identifying unique studies, and that over 60% of all studies were identified by multiple sources.54 Although we were able to identify a large number of studies, many of them used different definitions for PTB and most did not identify the clinical pathway to PTB; as a consequence, these data could not be pooled and not all of the existing evidence could be summarised in this review.

In conclusion, our study reaffirmed that a previous sPTB is a significant risk factor for recurrence in subsequent pregnancies, placing that risk at 30%. However, substantial heterogeneity in underlying studies speaks to the need for common definitions and further work in this area. Additionally, the absolute risk of recurrence appears to be substantially higher if the underlying aetiology is PTL as opposed to PPROM. Clinically, this information will help with risk stratification and patient counselling. Interventions to prevent PTB need to be focused and designed for specific clinical conditions. Further studies need to be done that look at the efficacy of preventative treatments in the prevention of PTL and PPROM. Knowledge of the aetiology of previous sPTB may help to identify women at increased risk of sPTB for participation in future clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made a substantial contribution to this study. CP, ZV and CH conducted the systematic review. CP drafted the manuscript. AM designed the study and conducted the meta-analysis. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript, interpreted the findings, and approved the final version. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. As the senior author AM affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Funding: This study was funded by the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. Amy Metcalfe is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funder had no role in study design, execution, or publication decisions.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data is available.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it first published. The word 'TEST' has been removed from the first line of the Introduction.

References

- 1. Dimes M. PMNCH, save the Children, WHO. the global action report on preterm birth. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. . National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379:2162–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering T. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? where? why? Lancet 2005;365:891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012;379:2151–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. . Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:75–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, et al. . Recurrent preterm birth. Semin Perinatol 2007;31:142–58. 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Epidemiology of preterm birth and its clinical subtypes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2006;19:773–82. 10.1080/14767050600965882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim G, Tracey J, Boom N, et al. . CIHI survey: Hospital costs for preterm and small-for-gestational age babies in Canada. Healthc Q 2009;12:20–4. 10.12927/hcq.2013.21121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDonald SW, Kingston D, Bayrampour H, et al. . Coping resources, and preterm birth. Arch Womens Ment Health 2014;17:559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shapiro GD, Fraser WD, Frasch MG, et al. . Psychosocial stress in pregnancy and preterm birth: associations and mechanisms. J Perinat Med 2013;41:631–45. 10.1515/jpm-2012-0295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Loomans EM, van Dijk AE, Vrijkotte TG, et al. . Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:485–91. 10.1093/eurpub/cks097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. . The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis Ottawa. ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2014. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 2014;72:39 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ananth CV, Getahun D, Peltier MR, et al. . Recurrence of spontaneous versus medically indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:643–50. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asrat T, Lewis DF, Garite TJ, et al. . Rate of recurrence of preterm premature rupture of membranes in consecutive pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165(4 Pt 1):1111–5. 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90481-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Care AG, Sharp AN, Lane S, et al. . Predicting preterm birth in women with previous preterm birth and cervical length ≥ =25 mm. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;43:681–6. 10.1002/uog.13241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carr-Hill RA, Hall MH. The repetition of spontaneous preterm labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985;92:921–8. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb03071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coleman S, Wallace L, Alexander J, et al. . Recurrent preterm birth in women treated with 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate: the contribution of risk factors in the penultimate pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:1034–8. 10.3109/14767058.2011.614657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crane JM, Hutchens D. Use of transvaginal ultrasonography to predict preterm birth in women with a history of preterm birth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;32:640–5. 10.1002/uog.6143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drassinower D, Obi?an SG, Siddiq Z, et al. . Does the clinical presentation of a prior preterm birth predict risk in a subsequent pregnancy? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:686.e1–686.e7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ekwo E, Moawad A. The risk for recurrence of premature births to African-American and white women. J Assoc Acad Minor Phys 1998;9:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elimian A, Smith K, Williams M, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of intramuscular versus vaginal progesterone for the prevention of recurrent preterm birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;134:169–72. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Esplin MS, O'Brien E, Fraser A, et al. . Estimating recurrence of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:516–23. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184181a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Getahun D, Strickland D, Ananth CV, et al. . Recurrence of preterm premature rupture of membranes in relation to interval between pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:570.e1–570.e6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glover MM, McKenna DS, Downing CM, et al. . A randomized trial of micronized progesterone for the prevention of recurrent preterm birth. Am J Perinatol 2011;28:377–81. 10.1055/s-0031-1274509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Faye-Petersen O, et al. . The Alabama preterm Birth Project: placental histology in recurrent spontaneous and indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:792–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Cordova YC, Istwan NB, et al. . Influence of gestational age and reason for prior preterm birth on rates of recurrent preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:275.e1–275.e5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harper M, Thom E, Klebanoff MA, et al. . Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation to prevent recurrent preterm birth: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115(2 Pt 1):234–42. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd60e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Himes KP, Simhan HN. Risk of recurrent preterm birth and placental pathology. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:121–6. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318179f024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hsieh TT, Chen SF, Shau WY, et al. . The impact of interpregnancy interval and previous preterm birth on the subsequent risk of preterm birth. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2005;12:202–7. 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Laughon SK, Albert PS, Leishear K, et al. . The NICHD Consecutive Pregnancies Study: recurrent preterm delivery by subtype. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:131.e1–131.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lykke JA, Paidas MJ, Langhoff-Roos J. Recurring complications in second pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:1217–24. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a66f2d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Manuck TA, Henry E, Gibson J, et al. . Pregnancy outcomes in a recurrent preterm birth prevention clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:320.e1–320.e6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Markham KB, Walker H, Lynch CD, et al. . Preterm birth rates in a prematurity prevention clinic after adoption of progestin prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:34–9. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. . Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2379–85. 10.1056/NEJMoa035140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Moawad AH, et al. . The preterm prediction study: effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181(5 Pt 1):1216–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Owen J, Yost N, Berghella V, et al. . Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. JAMA 2001;286:1340–8. 10.1001/jama.286.11.1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rittenberg C, Newman RB, Istwan NB, et al. . Preterm birth prevention by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate vs. daily nursing surveillance. J Reprod Med 2009;54:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Turitz AL, Bastek JA, Purisch SE, et al. . Patient characteristics associated with 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate use among a high-risk cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:536.e1–536.e5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vermeulen GM, Bruinse HW. Prophylactic administration of clindamycin 2% vaginal cream to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women with an increased recurrence risk: a randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999;106:652–7. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vogel I, Goepfert AR, Thorsen P, et al. . Early second-trimester inflammatory markers and short cervical length and the risk of recurrent preterm birth. J Reprod Immunol 2007;75:133–40. 10.1016/j.jri.2007.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wallace JM, Bhattacharya S, Campbell DM, et al. . Inter-pregnancy weight change and the risk of recurrent pregnancy complications. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154812 10.1371/journal.pone.0154812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yamashita M, Hayashi S, Endo M, et al. . Incidence and risk factors for recurrent spontaneous preterm birth: A retrospective cohort study in Japan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1708–14. 10.1111/jog.12786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang J, Baer RJ, Berghella V, et al. . Recurrence of preterm birth and early term birth. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:364–72. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uquillas KR, Fox NS, Rebarber A, et al. . A comparison of cervical length measurement techniques for the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30:50–3. 10.3109/14767058.2016.1160049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kazemier BM, Buijs PE, Mignini L, et al. . Impact of obstetric history on the risk of spontaneous preterm birth in singleton and multiple pregnancies: a systematic review. BJOG 2014;121:1197–208. discussion 209 10.1111/1471-0528.12896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kamath-Rayne BD, DeFranco EA, Chung E, et al. . Subtypes of preterm birth and the risk of postneonatal death. J Pediatr 2013;162:28–34. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Villar J, Abalos E, Carroli G, et al. . Heterogeneity of perinatal outcomes in the preterm delivery syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:78–87. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000130837.57743.7b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen A, Feresu SA, Barsoom MJ. Heterogeneity of preterm birth subtypes in relation to neonatal death. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:516–22. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b473fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Newman DE, Paamoni-Keren O, Press F, et al. . Neonatal outcome in preterm deliveries between 23 and 27 weeks' gestation with and without preterm premature rupture of membranes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:7–11. 10.1007/s00404-008-0836-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Basso O, Wilcox A. Mortality risk among preterm babies: immaturity versus underlying pathology. Epidemiology 2010;21:521–7. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181debe5e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brown HK, Speechley KN, Macnab J, et al. . Neonatal morbidity associated with late preterm and early term birth: the roles of gestational age and biological determinants of preterm birth. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:802–14. 10.1093/ije/dyt251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Newnham JP, Dickinson JE, Hart RJ, et al. . Strategies to prevent preterm birth. Front Immunol 2014;5:584 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Betrán AP, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. . Effectiveness of different databases in identifying studies for systematic reviews: experience from the WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:6 10.1186/1471-2288-5-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015402supp001.pdf (157.6KB, pdf)