Abstract

Background

Highly sensitive troponin T (hs-TnT) assay has improved clinical decision-making for patients admitted with chest pain. However, this assay’s performance in detecting myocardial ischaemia in a lowrisk population has been poorly documented.

Purpose

To assess hs-TnT assay’s performance to detect myocardial ischaemia at positron emission tomography/CT (PET-CT) in low-risk patients admitted with chest pain.

Methods

Patients admitted for chest pain with a nonconclusive ECG and negative standard cardiac troponin T results at admission and after 6 hours were prospectively enrolled. Their hs-TnT samples were at T0, T2 and T6. Physicians were blinded to hs-TnT results. All patients underwent a PET-CT at rest and during adenosine-induced stress. All patients with a positive PET-CT result underwent a coronary angiography.

Results

Forty-eight patients were included. Six had ischaemia at PET-CT. All of them had ≥1 significant stenosis at coronary angiography. Areas under the curve (95% CI) for predicting significant ischaemia at PET-CT using hs-TnT were 0.764 (0.515 to 1.000) at T0, 0.812(0.616 to 1.000) at T2 and 0.813(0.638 to 0.989) at T6. The receiver operating characteristicbased optimal cut-off value for hs-TnT at T0, T2 and T6 needed to exclude significant ischaemia at PET-CT was <4 ng/L. Using this value, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of hs-TnT to predict significant ischaemia were 83%/38%/16%/94% at T0, 100%/40%/19%/100% at T2 and 100%/43%/20%/100% at T6, respectively.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that in low-risk patients, using the hs-TnT assay with a cut-off value of 4 ng/L demonstrates excellent negative predictive value to exclude myocardial ischaemia detection at PET-CT, at the expense of weak specificity and positive predictive value.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01374607.

Keywords: troponin, acute coronary syndrome, positron emission tomography, ischemia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In this study, we showed an additive diagnostic value of high-sensitive troponin T over standard troponin in detection of myocardial ischaemia as assessed by the gold standard imaging modality—positron emission tomography/CT (PET-CT) in a clinically difficult population of patients with chest pain, non-conclusive ECG and negative standard cardiac troponin and low risk of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Even within a normal range of high-sensitive troponin T concentration, a cut-off level may be identified to further improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce false-negative and false-positive results indicative for myocardial ischaemia as assessed by PET-CT.

We provide data, supported by the PET-CT study, on non-inferiority of the shortening of troponin protocols for ruling out an ACS in the emergency department from 6 to 2 hours interval.

The study sample and single-centre character of the study warrants careful interpretation of outcomes and further research on larger population, preferably multicentric.

Time intervals of blood sampling were adopted from European guidelines so the implementation of outcomes is limited in respect to ongoing research on different strategies maximally shortening diagnostic protocols.

Introduction

Patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) represent a large population of those admitted to emergency departments.1 Recent available high-sensitive troponin T (hs-TnT) assay has improved the detection of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in terms of its speed and sensitivity over standard cardiac troponin (cTn) assays.2 The hs-TnT assay was recently incorporated into the clinical decision algorithm of the latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines.3 However, despite its better sensitivity, the hs-TnT assay has a lower specificity because positive values are driven by several non-coronary cardiac and non-cardiac clinical conditions. The introduction of the hs-TnT assay has therefore led to more false-positive results and subsequent unnecessary hospitalisations. When cardiac troponin levels are negative at different time points, current recommendations propose using a stress imaging test to identify patients at risk of cardiac events. The added value of the hs-TnT assay over the standard cTn assay in this population of patients is poorly documented, however. The aim of this study was therefore to assess the performance of the hs-TnT assay to detect myocardial ischaemia at positron emission tomography/CT (PET-CT) in a population of patients admitted for chest pain with negative standard cTn.

Materials and methods

Trial oversight

The study was conducted after regulatory and ethical approval was obtained from the local ethical commission (protocol 18/11) and it was duly registered on clinicaltrial.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01374607).

Sample population

Patients admitted to the emergency department for chest pain were prospectively enrolled in the study. Inclusion criteria were: acute chest pain lasting ≥5 min within the last 24 hours and negative standard cTn results at admission (T0) and after 6 hours (T6). Exclusion criteria were: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; major organ dysfunction, infection or major medical conditions (uncontrolled asthma, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AV-block of the II or III degree without a pacemaker) that would compromise the patient's ability to undergo a hyperemic, adenosine-induced stress test; cancer with expected survival <6 months; pregnancy or age <18 years. At admission, a clinical examination was performed and an ECG was used to screen for acute myocardial ischaemia according to international standards.4 Information on cardiovascular risk factors, any past medical history of cardiovascular diseases and current medical treatment were collected. All patients were stratified according to their thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) risk score and the score of 0 or 1 was indicative for low risk of cardiovascular adverse events.5

Troponin measurements

The standard cTn assay, routinely used in the institution throughout the enrolment process, was cardiac troponin I measured with AccuTnI assay (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California, USA), with a 99th percentile level of 0.04 µg/L and a 20% coefficient of variation at 0.03 µg/L and considered as positive if above the 99th percentile. The hs-TnT value was measured in parallel to the standard cTnI assay, using the same plasma samples at T0, T2 and T6. Concentrations of hs-TnT in plasma were measured using a Cobas e602 immunoanalyzer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) based on electrochemiluminescence technology (detection range of 3–10 000 ng/L, with a 99th percentile level in a normal population of 14 ng/L and a 10% coefficient of variation level of 13 ng/L). The 2-hour diagnostic protocol using cTn has been described previously to carry a good diagnostic accuracy.6

PET-CT and coronary angiography

All patients underwent a rubidium-82 (Rb-82) rest–stress cardiac PET-CT acquisition (Discovery 690, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) according to a previously described method.7 Patients were instructed to fast for 6 hours and the absence of any caffeine intake in the previous 24 hours was checked. Dynamic rest acquisition started after the beginning of an intravenous infusion of 10 MBq/kg of Rb-82 (Jubilant Draximage, Kirkland, Canada).8 Ten minutes later, a hyperaemic stress test was performed using a slow intravenous infusion of adenosine (140 µg/kg/min) over 6 min. A second PET-CT acquisition was started 2 min after the beginning of adenosine infusion. PET-CT images were analysed semi-quantitatively by two independent nuclear medicine specialists using the 17-segment AHA polar map9 to reveal the extent and severity of perfusion defects at rest (summed rest score (SRS)) and during stress (summed stress score (SSS)), as well as inducible ischaemia as defined by the summed difference score (SDS=SSS-SRS). Absolute quantitation of myocardial blood flow (MBF) at rest and during stress, as well as the myocardial flow reserve (MFR=stress MBF/rest MBF), were computed using FlowQuant (Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Canada). Both, SDS and MFR have been documented as having a prognostic value in patients investigated for ischaemia.7 10 A PET-CT is likely to be positive for myocardial ischaemia when SDS is >2 or MFR is <1.8. These two thresholds have been shown to be strong predictors of major cardiovascular events.7 11 Patients in the present study who were positive for myocardial ischaemia on PET-CT images were scheduled for a coronary angiography.

The results of coronary angiography were assessed visually by two independent investigators, with an assessment by a third interventional cardiologist in cases of borderline stenosis. Stenosis of an epicardial coronary artery was defined as significant if the diameter of the stenosis was >50% of the lumen diameter in an artery with a diameter >2 mm.

Major adverse cardiac events

Patients were followed-up with phone calls 30 days after discharge and evaluated for any major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), defined as rehospitalisation for a cardiovascular reason, repeated revascularisation, non-fatal AMI or death of a cardiovascular origin.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (V.19, SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and GraphPad Prism V.6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA). Variables are presented as a mean±SD or as a median and its IQR. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Comparisons of categorical data were performed using the Fischer's exact test or the χ2 test, as appropriate. A bilateral p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed by plotting each patient’s values of hs-TNT at T0, T2 and T6 against the presence of ischaemia at PET-CT. Best cut-offs were calculated using Youden’s index.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the sample population

Of 50 eligible patients, 2 were excluded due to technical problems during the PET-CT quantitation of flow reserve. The remaining 48 patients participating in the study had a median (P25; P75) duration of chest pain of 2 hours (1; 4); mean age was 58±13 years; 33 (68%) were males; 7 (15%) had diabetes; 3 (6%) had a history of myocardial infarction; 15 (31%) had prior percutaneous coronary intervention and 1 (2%) had prior coronary artery bypass graft. The median TIMI risk score was 1 (0; 2) (table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Total population (n=48) | Without ischaemia (n=42) | With ischaemia (n=6) |

| Past medical history | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (33%) |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 15 (31%) | 12 (29%) | 3 (50%) |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) |

| Stroke | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (17%) |

| Renal insufficiency | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 28 (58%) | 22 (52%) | 6 (100%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 26 (54%) | 20 (48%) | 6 (100%) |

| Diabetes | 7 (15%) | 6 (14%) | 1 (17%) |

| Familial history | 15 (31%) | 14 (33%) | 1 (17%) |

| Current/former smoking | 20 (42%) | 18 (43%) | 2 (33%) |

| TIMI risk score | 1 (0 to 2) | 0 (0 to 0) | 2 (2 to 3) |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Systolic blood pressure | 135 (119 to 155) | 135 (122 to 152) | 142 (129 to 154) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 75 (66 to 82) | 75 (69 to 82) | 64 (62 to 78) |

| Heart rate | 72 (60 to 88) | 73 (62 to 88) | 65 (53 to 75) |

| Body mass index | 27.8 (25.3 to 30.4) | 27.3 (25.3 to 29.8) | 28.8 (26.5 to 30.7) |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (25th; 75th percentile).

TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

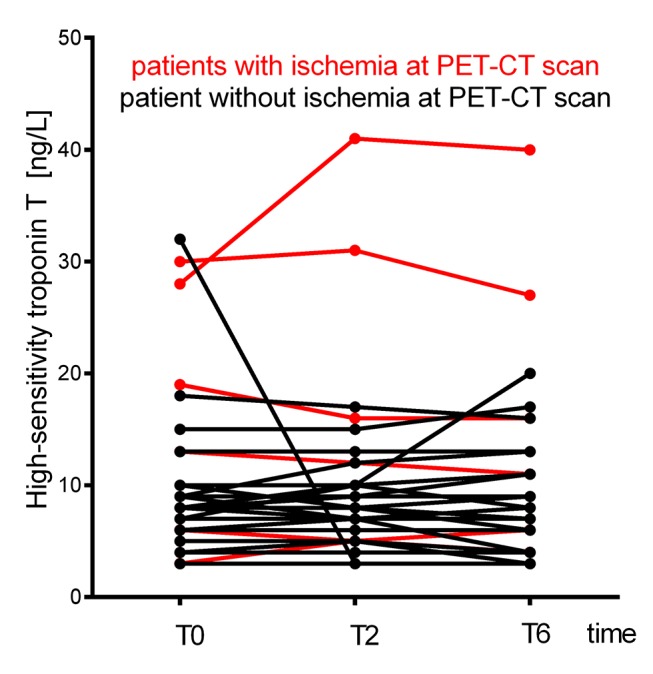

Levels of hs-TnT in the sample population

As per the study design, standard cTn levels were <99th percentile (<0.03 mg/L) in all patients at T0 and T6. First blood sample for hs-TnT measurement was taken after a median of 4 hours 8 min after first chest pain and after a median of 1 hour 28 min after the last episode. Median hs-TnT levels for the sample population were 6.0 (3.0 to 9.0) ng/L at T0; 5.5 (3.0 to 9.0) ng/L at T2, and 5.0 (3.0 to 9.0) ng/L at T6. These hs-TnT values remained stable over time, with a mean absolute change of 0.29 ng/L within the first 2 hours after admission, and of 0.021 ng/L in the following 4 hours (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Plot of highly sensitive troponin T concentrations at admission (T0) and at 2 hours (T2) and 6 hours (T6) afterwards. PET-CT, positron emission tomography/CT.

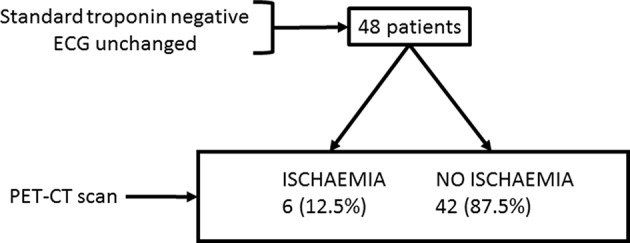

Identification of inducible ischaemia with PET-CT

A PET-CT was performed with a median delay of 32 hours (17 to 65) from symptom onset. Among the 48 patients, 6 (12.5%) had a positive PET-CT for myocardial ischaemia (Figure 2). In all patients diagnosed positive for myocardial ischaemia, a coronary angiography confirmed at least one significant epicardial coronary artery stenosis.

Figure 2.

Study chart. PET-CT, positron emission tomography/CT.

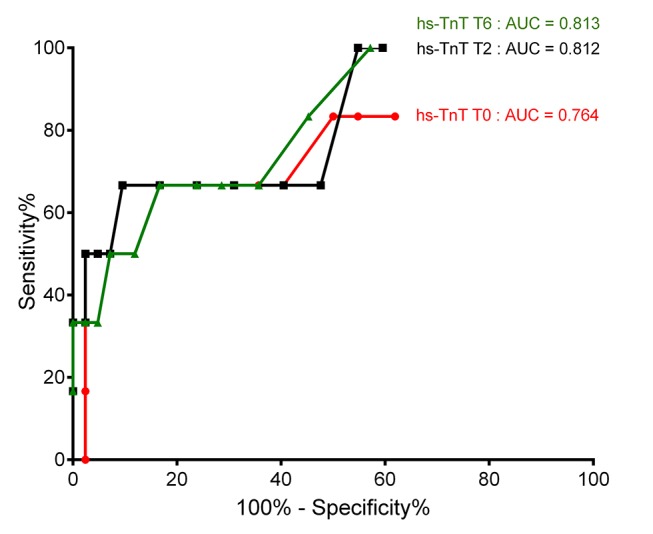

ROC curves

Areas under the ROC curves were calculated for hs-TnT at T0, T2 and T6, both with and without absolute delta changes. The areas under the curves (95% CI) obtained were: 0.764 (0.515 to 1.000) (T0); 0.812 (0.616 to 1.000) (T2); 0.806 (0.601 to 1.000) (T0, T2 and delta change); 0.813 (0.638 to 0.989) (T6) and 0.829 (0.634 to 1.000) (T0, T2, T6 and delta changes) (Figure 3). Additional analyses with different absolute values for hs-TnT and incorporation of the absolute delta changes improved the area under the curves, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the detection of myocardial ischaemia. AUC, area under the curve; hs-TnT, highly sensitive troponin T.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and diagnostic accuracy

The ROC-based, optimal cut-off value for hs-TnT value at T0, T2 and T6 necessary to exclude a diagnosis of significant ischaemia at a PET-CT was <4 ng/L. Such concentration was met by 17 (35%) patients at T0 and T2 and 18 (38%) patients at T6. Using this value, the sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values of the hs-TnT assay to predict significant ischaemia at PET-CT were 83 (36% to 99%), 38 (24% to 54%), 16 (6% to 34%), 94 (69% to 100%) at T0, 100 (52% to 100%), 40 (26% to 57%), 19 (8% to 38%), 100 (77% to 100%) at T2 and 100 (52% to 100%), 43 (28% to 59%), 20 (8% to 39%), 100 (78% to 100%) at T6 (table 2). Using the recommended cut-off value of the 99th percentile at 14 ng/L, the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of the hs-TnT assay were 50 (14% to 86%), 93 (79% to 98%), 50 (14% to 86%), 93 (79% to 98%) at T0, 50 (14% to 86%), 95 (83% to 99%), 60 (17% to 93%), 93 (79% to 98%) at T2 and 50 (14% to 86%), 93 (79% to 98%), 50 (14% to 86%), 93 (79% to 98%) at T6.

Table 2.

The hs-TnT assay’s performance in predicting the detection of ischaemia at PET-CT

| hs-TnT ≥4 ng/L at: | T0 | T2 | T6 |

| Sensitivity | 83.33% (36.48 to 99.12) | 100% (51.68 to 100.00) | 100% (51.68 to 100.00) |

| Specificity | 38.10% (23.99 to 54.35) | 40.48% (26.02 to 56.65) | 42.85% (28.08 to 58.93) |

| Positive predictive value | 16.13% (6.09 to 34.47) | 19.35% (8.12 to 38.06) | 20% (8.40 to 39.13) |

| Negative predictive value | 94.12% (69.24 to 99.69) | 100% (77.08 to 100.00 to) | 100% (78.12 to 100.0 to) |

| Area under the curve | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.00) | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.00) | 0.81 (0.64 to 0.99) |

hs-TnT, highly sensitive troponin T; PET-CT, positron emission tomography/CT.

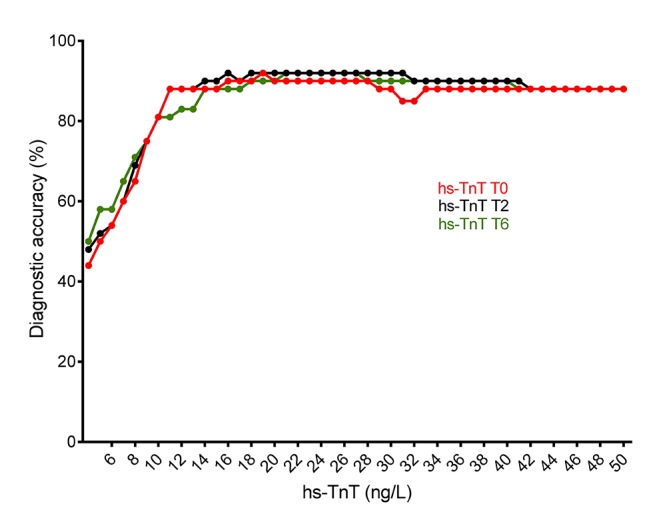

The performance accuracy of different hs-TnT cut-off values was assessed at T0, T2 and T6 (Figure 4). The highest prediction values at T0, T2 and T6 were observed with cut-off values of 19, 18 and 21 ng/L, respectively, with a performance accuracy of 91.6% for each time point.

Figure 4.

Diagnostic accuracy. hs-TnT, highly sensitive troponin T.

Follow-up

During the 30-day follow-up period, no adverse cardiovascular events were reported in any of the 48 patients.

Discussion

The recently introduced hs-TnT assays are the most sensitive markers of myocardial necrosis. Their recommendation in European guidelines for ACS management3 has been validated by several clinical trials that showed the assay’s high diagnostic accuracy2 12 and greater prognostic accuracy than standard cTn assay.3 However, the hs-TnT assay’s diagnostic performance for the detection of myocardial ischaemia in a low-risk profile population had been poorly documented. We chose myocardial blood flow quantitation, using a Rb-82 PET-CT, as a non-invasive stress test to detect myocardial ischaemia.

The present study showed that hs-TnT assay measurements in a population of low-risk ACS profile patients at T0, T2 and T6 provided low specificity and low positive predictive values but an excellent sensitivity and negative predictive values (94%, 100% and 100%, respectively) for predicting the detection of ischaemia as assessed using a PET-CT at a cut-off of 4 ng/L. Moreover, measurements at T2 provided higher negative predictive values than at T0 and equal to values at T6. In other words, T2 might be considered as potentially valuable time point at which to exclude ischaemia in this specific population but this finding warrants further studies on larger cohorts.

Current European guidelines on the management of ACS in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation have introduced algorithms for ruling-in and ruling-out acute myocardial infarction. In patients with hs-TnT levels below the 99th percentile, without ischaemic changes on ECGs and free of chest pain for several hours, these guidelines propose a stress imaging test at the time of admission or shortly after discharge. Nevertheless, the exact timing of these investigations remains unclear and the treatment regimen during a potential discharge remains a typical daily dilemma for clinicians. Indeed, a recent prospective study based on data from 1400 patients with unstable angina suggested that adherence to the ESC guidelines was inadequate in nearly two-thirds of patients in terms of overtreatment or undertreatment.13 In a retrospective study based on 344 patients with chest pain, negative serial ECG and negative cardiac enzyme discharged before stress testing, 2 patients had a fatal out-of-hospital cardiac event and 24 were readmitted to the emergency department prior to carrying out stress testing.14 In addition, data based on 966 patients with unstable angina who were mistakenly discharged were analysed as part of a multicentre trial. Their risk-adjusted mortality ratio was 1.7 times higher than those who were hospitalised (95% CI 0.2 to 17.0).15 Different studies evaluating the safety of discharge before stress testing based solely on negative hs-TnT values have been recently published. In a general population of patients suspected for ACS, it was documented that single normal troponin measurement at admission (below the 99th percentile) was not a reliable method to safely rule-out patients suspected for ACS.16 The safety of ruling-out an ACS was also examined in regard to undetectable levels of hs-Tn at admission, showing high negative predictive value for this strategy.17 18 The present study identified a cut-off of 4 ng/L for hs-TnT at T2, and not admission, as being sufficient for exclusion of ischaemia at PET-CT and effective decision-making process in a low-risk ACS profile population. Indeed, no patient with hs-TnT values at T2 and T6 below this cut-off had ischaemia at PET-CT and none of them experienced MACE. The proportion of patients in the present study with hs-TnT <4 ng/L at T2 was 35% (17 patients) and at T6 was 38% (18 patients). Accordingly, using an algorithm to allow the discharge of patients with a low-risk of ACS, based on a cut-off of 4 ng/L at T2 without any stress imaging, would have allowed these patients to have been discharged with a marginal probability of an occurrence of any MACEs at the 30-day follow-up. In a prospective cohort study of patients with suspected ACS, Shah et al concluded that low plasma troponin concentrations identify two-thirds of patients at very low risk of cardiac events who could be discharged from the hospital.19 However, in this study, the outcomes were index myocardial infarction, subsequent myocardial infarction or cardiac death at 30 days. In our study, we further support the safety of proposed hs-TnT algorithm, by showing no ischaemia in PET-CT for patients in the rule-out zone in a preselected low-risk population. However, even if the strategy of ruling-out AMI with single value of hs-TnT ranging from 3 to 5 ng/L appears safe (as reported in a recent meta-analysis20), safety concern remains regarding patients who present <3 hours after symptom onset.

Regarding the hs-TnT assay’s performance in the detection of myocardial ischaemia, it showed a low positive predictive value for detecting myocardial ischaemia at PET-CT in this specific population with a low-risk profile. Indeed, the lowest diagnostic accuracies in our study (44%, 48% and 50%) were observed at the 4 ng/L cut-off at T0, T2 and T6, respectively. On the other hand, the highest diagnostic accuracies were found with cut-off values of 19 , 18 and 21 ng/L at T0, T2 and T6, respectively, but with lower negative predictive values (93%, 91% and 91%). In other words, hs-TnT seems to be an excellent biomarker for excluding the diagnosis of myocardial ischaemia at PET-CT, rather than for detecting it in this specific population. Considering the combined accuracy for ruling-in and ruling-out, the algorithm of 2-hour change in hs-Tn level seems to outperform a single measure, what was shown and validated for hs-TnT in a general cohort of patients with chest pain.21 Nevertheless, an algorithm based on hs-TnT measurements, coupled with a PET-CT stress test, seems to diagnose functionally significant coronary artery stenosis correctly at angiogram if hs-TnT ≥4 ng/L. This assumption should be verified by using a coronary angiogram for all patients.

Limitation

One major limitation of the present study is its small number of participants, particularly those with a positive PET-CT. Another limitation is a verification bias, as coronary angiograms were not performed on patients with negative PET-CT. Indeed, the study investigated a low-risk ACS population, in which an invasive diagnostic strategy is not indicated. However, it could also be argued that all these patients had a negative PET-CT and no MACE during 30 days of follow-up.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that a cut-off <4 ng/L at T2 provided excellent negative predictive values (100%) for the exclusion of myocardial ischaemia as measured by PET-CT in a low-risk profile ACS population. Furthermore, in patients with hs-TnT ≥4 ng/L, a strategy based on a PET-CT ischaemia detection appears to be appropriate. These results should be confirmed in the study of a larger sample population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BM and SF contributed to the conception of the study, to acquisition and analysis of the data, performed analysis and prepared the draft of the manuscript. MT gave the design of the study, gathered and managed the data. JOP, PAM and VD gathered the data, gave critical view to the design and the draft of the manuscript. NL and FR participated in analysis and gathering of the data. CT, J-FI and DK gathered the data, performed analysis and participated in preparation of the manuscript. OB, DB and SL performed laboratory analyses and data management. EE, OH and OM participated in the design of the study, approved all analyses and gave critical overview to the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Informed consent approved by the local ethical committe was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethics approval: Ethical Commitee CHUV Lausanne.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2010;26:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. . Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med 2009;361:858–67. 10.1056/NEJMoa0900428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. . 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1581–98. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. . The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA 2000;284:835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Than M, Cullen L, Aldous S, et al. . 2-Hour accelerated diagnostic protocol to assess patients with chest pain symptoms using contemporary troponins as the only biomarker: the ADAPT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:2091–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farhad H, Dunet V, Bachelard K, et al. . Added prognostic value of myocardial blood flow quantitation in rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;14:1203–10. 10.1093/ehjci/jet068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kajander S, Joutsiniemi E, Saraste M, et al. . Cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging accurately detects anatomically and functionally significant coronary artery disease. Circulation 2010;122:603–13. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.915009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tilkemeier PL, Wackers FJ. Quality Assurance Committee of the American Society of Nuclear C. myocardial perfusion planar imaging. J Nucl Cardiol 2006;13:e91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ziadi MC, Dekemp RA, Williams KA, et al. . Impaired myocardial flow reserve on rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging predicts adverse outcomes in patients assessed for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:740–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukushima K, Javadi MS, Higuchi T, et al. . Prediction of short-term cardiovascular events using quantification of global myocardial flow reserve in patients referred for clinical 82Rb PET perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med 2011;52:726–32. 10.2967/jnumed.110.081828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thygesen K, Mair J, Katus H, et al. . Recommendations for the use of cardiac troponin measurement in acute cardiac care. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2197–204. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Breuckmann F, Hochadel M, Darius H, et al. . Guideline-adherence and perspectives in the acute management of unstable angina - Initial results from the German chest pain unit registry. J Cardiol 2015;66:108–13. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lai C, Noeller TP, Schmidt K, et al. . Short-term risk after initial observation for chest pain. J Emerg Med 2003;25:357–62. 10.1016/S0736-4679(03)00238-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. . Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1163–70. 10.1056/NEJM200004203421603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoeller R, Rubini Giménez M, Reichlin T, et al. . Normal presenting levels of high-sensitivity troponin and myocardial infarction. Heart 2013;99:1567–72. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rubini Giménez M, Hoeller R, Reichlin T, et al. . Rapid rule out of acute myocardial infarction using undetectable levels of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:3896–901. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Body R, Carley S, McDowell G, et al. . Rapid exclusion of acute myocardial infarction in patients with undetectable troponin using a high-sensitivity assay. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1332–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shah AS, Anand A, Sandoval Y, et al. . High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I at presentation in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet 2015;386:2481–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00391-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhelev Z, Hyde C, Youngman E, et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of single baseline measurement of elecsys troponin T high-sensitive assay for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in emergency department: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015;350:h15 10.1136/bmj.h15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boeddinghaus J, Reichlin T, Cullen L, et al. . Two-hour algorithm for triage toward rule-out and rule-in of acute myocardial infarction by use of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I. Clin Chem 2016;62:494–504. 10.1373/clinchem.2015.249508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.