Abstract

Introduction

A considerable number of clinical studies experience delays, which result in increased duration and costs. In multicentre studies, patient recruitment is among the leading causes of delays. Poor site selection can result in low recruitment and bad data quality. Site selection is therefore crucial for study quality and completion, but currently no specific guidelines are available.

Material and methods

Selection of sites adequate to participate in a prospective multicentre cohort study was performed through an open call using a newly developed objective multistep approach. The method is based on use of a network, definition of objective criteria and a systematic screening process.

Illustrative example of the method at work

Out of 266 interested sites, 24 were shortlisted and finally 12 sites were selected to participate in the study. The steps in the process included an open call through a network, use of selection questionnaires tailored to the study, evaluation of responses using objective criteria and scripted telephone interviews. At each step, the number of candidate sites was quickly reduced leaving only the most promising candidates. Recruitment and quality of data went according to expectations in spite of the contracting problems faced with some sites.

Conclusion

The results of our first experience with a standardised and objective method of site selection are encouraging. The site selection method described here can serve as a guideline for other researchers performing multicentre studies.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02297581.

Keywords: site selection, methodology, clinical research, multicenter studies

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Provides a systematic and objective approach to site selection.

May serve as a practical guideline to optimise site selection.

Adaptable for use in different fields.

Eventual contractual difficulties are not addressed early enough.

Application is limited to multicentre clinical studies.

Introduction

Clinical research demands careful consideration of ethical, scientific, methodological and operational aspects. A significant number of clinical trials experience delays,1 which can extend the duration of a given study by up to 50% of its originally planned time. The reasons for delays are numerous and methods to reduce them must be ensured. Patient recruitment is among the leading causes,2 which is not surprising if we consider that reportedly many sites will not enrol the number of patients expected at the beginning of the study.3–6 Sites unable to recruit enough patients increase the length of the enrolment period and become an economic burden. The time and cost of training, opening and maintaining a site can represent a considerable amount and underperforming sites cannot justify this expense.4 5 In addition, sites with insufficient experience are more likely to incur in protocol violations or to have low-quality data that will require further training, on-site visits and more queries for clarification, all of which have an impact on costs and study duration. Choosing appropriate sites able to recruit an adequate number of patients while maintaining high-quality data is crucial for timely and successful completion of studies.

Several aspects play a role in selecting a site for sponsored multicentre clinical studies. First and most importantly, a site taking part in a given clinical trial must have access to a relatively high volume of patients meeting the eligibility criteria, expertise in the area, appropriate facilities or equipment and trained investigators eager to perform research. In addition, previous research experience of the study site provides an indicator of past performance in recruitment and data quality. Familiarity with trial procedures such as contracting, informed consent process and submissions to ethical and regulatory authorities is a great advantage as these aspects may be a great hurdle.7 The operational aspects to take into consideration during site selection are the availability of dedicated staff (such as a study coordinator and trained investigators), use of quality systems and specific requirements of ethical committees that may affect speed of approvals.8

Despite the importance of site selection for clinical studies, there are currently no detailed guidelines available3 9 about how site selection should be done in a systematic way. In general, the typical site selection process may include reviewing epidemiological data to find locations with a high incidence of the disease of interest, collecting site selection surveys to evaluate feasibility and verification of the capability and willingness of the site to complete the study.9

Clinical research in surgically related topics faces several challenges.10 It requires patients willing to participate, doctors with appropriate skills and expertise on the particular technique(s) or devices under study, and in some occasions advanced infrastructure. In summary, patient availability, surgeons’ willing and able to perform the clinical study in question and fulfilment of the specific requirements for each study must come together to make a site suitable for participation. Convergence of all the above factors in one site proves very difficult and must be carefully evaluated along with organisational and regulatory aspects.

Our organisation has been performing clinical research for the last 15 years, and the selection of sites for our previous studies was mostly based on a common scientific interest from a group of surgeons. Over the years, we had studies with low recruitment in several occasions and strategies to overcome it had to be implemented during the course of such studies: extend the recruitment period beyond its originally planned time, adding new sites while closing those with poor performance or even cancelling a study before accrual completion. All of the above resulted in extended timeframes and higher costs. To improve site selection, a more standardised, objective and systematic approach was developed. The method described here was used for the first time in a prospective multicentre cohort study to evaluate the benefit of geriatric fracture centres (GFC) over usual care centres (UCC) (referred to as ‘GFC study’11 from here onwards, ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02297581). The purpose of the present article is to describe the methodology developed to standardise our site selection process for multicentre clinical studies. The GFC study is used as an example to illustrate how the method works and the results obtained with this first experience.

Methods

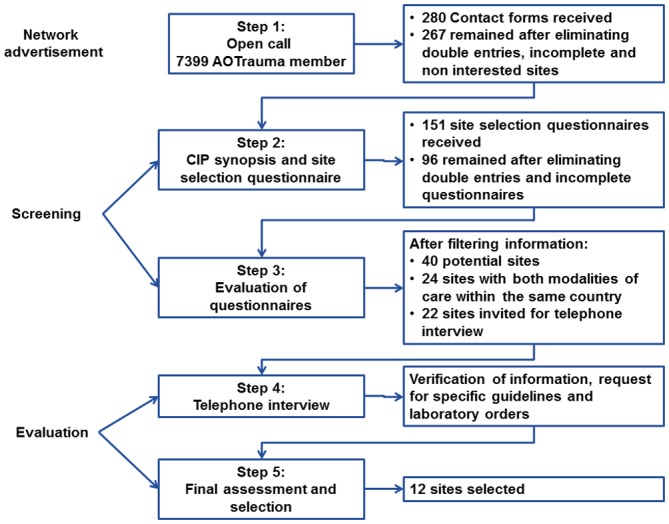

To identify suitable sites from all around the world, the site selection method used for the GFC study was based on a multistep approach (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps of the site selection process. CIP, Clinical Investigation Plan.

In general, the specific characteristics of each study are determined by the study design. Once the main points of the study protocol are defined (patient population, study procedures and specific requirements), searching for adequate sites for the study can be initiated. In studies in which feasibility is challenging, the site selection process can identify specific difficulties. These might be addressed in the study protocol that can be developed at a later time point.

Open call

Taking advantage of a worldwide network of orthopaedic trauma surgeons, an open call was made to all members in the form of an email blast. The message explained briefly the aim of the study and the study design. Surgeons with interest in participating in the study could fill in an online form with their contact details to receive more information (see online supplementary material 1). All data were collected and managed using REDCap12 (Research Electronic Data Capture). The initial deadline for submission of contact forms was 14 days after the open call was launched, and it was extended for 10 further days for a total of 24 days. During that period, one email reminder was sent.

bmjopen-2016-014796supp001.pdf (12.6KB, pdf)

Further information to interested sites and site selection questionnaire

In this second step, the synopsis of the Clinical Investigation Plan (CIP) (study protocol published jointly11) was sent via email to all those that expressed interest in the study and filled in the online contact form. The CIP synopsis gave more detailed information about the study background, objectives, study design, hypothesis, statistical considerations, eligibility criteria, outcome measures, follow-up procedures and timelines. After reading the CIP synopsis, surgeons still interested in taking part in the study could fill in the online REDCap site selection questionnaire using the link embedded in the same email. This questionnaire was adapted from a template available in our quality management system and gathers information regarding the hospital, principal investigator, staff, access to clinical trial unit, previous experience, availability for monitoring visits, organisation, ethics committee and contractual processes. The template was tailored by including questions to evaluate the specific aspects relevant to this study and which would become the first focal point for selection such as patient population, standard of care for geriatric patient management and organisation of the orthopaedic patient management (see online supplementary material 2). The estimated time for completion of the questionnaire was 30–60 min, and the deadline for submission was set 2 weeks later.

bmjopen-2016-014796supp002.pdf (20.4KB, pdf)

Evaluation of site selection questionnaires

Data stored in REDCap from the site selection questionnaires were exported into an Excel file for ease of handling. On evaluation of the questionnaires, requirements considered mandatory were evaluated first,9 13 namely identifying appropriate GFC and UCC sites within the same country. First, potential GFC were identified according to the specific criteria detailed in the CIP (see online supplementary material 2, Section 3). In the next step, a comparable UCC within the same country was identified. Given the fact that economic evaluations were considered in the analysis, the design required that in each participating country a GFC and a UCC were selected to allow a matched comparison of the different healthcare systems later on. In both cases, the number of patients as well as available qualified staff, resources and operational aspects were taken into consideration for the selection of each site.

Telephone interview

Sites that passed the evaluation filters of the previous step were invited for a telephone interview to verify the information provided in the site selection questionnaire and to obtain more information about the appropriateness of the site. The duration of the telephone interview was 30–45 min and for every call, a previously prepared script (see online supplementary material 3), tailored according to the answers provided, was used. During this call, questions were focused on the number of patients available, criteria to qualify for either a GFC or a UCC and ethical and contractual processes. The hospital guidelines to treat geriatric patients were requested at this point for the GFC group. Answers were written down on the scripts and evaluated to finalise the selection process. Sites were also encouraged to ask questions regarding the study or the selection process.

bmjopen-2016-014796supp003.pdf (82.9KB, pdf)

Final assessment and selection

The information provided in the telephone interview as well as the guidelines sent by the potential GFC were evaluated. Previous experience in clinical trials was also considered at this stage. Although we consider this an important aspect, care should be taken when choosing highly experienced sites as they might be involved in multiple trials, and this could limit the resources available for a new study. For this reason, the number of studies performed in the last 5 years and whether if studies in the same field are being performed or planned is always asked.

Final selection was done based on the previously defined criteria. Once the sites were selected, the submission to ethical committees and contracting process began.

Example of the method at work: First experience results with the gfc study

In the case of the GFC study, an observational cohort study design was chosen to determine the occurrence of major adverse events (AE, as defined in the CIP) in patients treated at geriatric fracture centres compared with the UCC. The observational, international and multicentre nature of this study allows a better evaluation of the effect of the two treatment concepts under real-life conditions. A GFC was defined as a site with a well-defined geriatric comanagement programme (involvement of a geriatrician in patient presurgical and postsurgical care, predefined guidelines for geriatric patient management and daily physiotherapy) as standard of care, whereas a UCC does not have such a well-defined geriatric comanagement programme. The study protocol has been detailed elsewhere11.

Open call

In the first step, 7399 email invitations were sent, of which 3874 were opened by the recipient. A total of 280 contact forms were received (3.8% response rate). After eliminating non-interested sites, double entries and contact forms with missing information, 266 valid forms from sites all over the world interested in study participation remained (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Contact forms received from interested sites divided by geographical region.

Further information to interested sites and site selection questionnaire

In the next step, the interested sites received a detailed site selection questionnaire. From the 266 site selection questionnaires sent out, we received 151 answers (56.5% response rate). Again duplicates or incomplete questionnaires were eliminated, leaving 96 (63.5%) applications for further assessment.

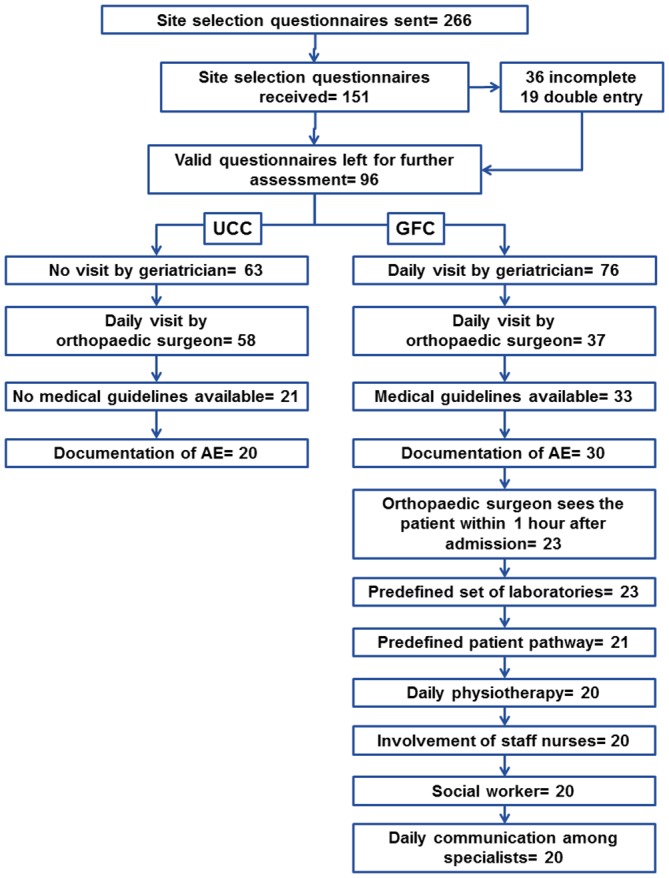

Evaluation of site selection questionnaires

The study design required to identify sites, which gathered the characteristics defined for a GFC or a UCC within the same country. Consequently, this became our first focal point for selection. After exporting the information given in REDCap to Microsoft Excel, filters were used to identify qualified centres for the study. For UCC, potential sites were identified applying the following filters: no daily round of a geriatrician, daily round by orthopaedic surgeon, no local medical guidelines for geriatric fracture management and documentation of AE. GFC sites fulfilled all the following criteria: daily visit of a geriatrician, daily visit of the orthopaedic surgeon, availability of medical guidelines, documentation of AE, orthopaedic surgeon sees the patient within 1 hour of admission, predefined set of laboratories, predefined patient pathway, daily physiotherapy, involvement of staff nurses, availability of social worker and daily communication among specialists. Figure 3 summarises the number of sites remaining after applying each filtering criterion. Out of the 96 complete site selection questionnaires, 20 potential UCC and GFC were identified. Therefore, at this stage of site selection, the list had been reduced to 40 sites in 22 countries. In the next step, countries in which both modalities of care existed were identified, resulting in 24 potential sites in nine countries. A summary of the number of sites matched per country is presented in table 1. One of the sites was involved in a competing clinical investigation, precluding their participation in our GFC study. Since there was only one site per modality of treatment in that country, the exclusion of one site left no counterpart for matched comparison, leading to the exclusion of both sites within the same country.

Figure 3.

Application of strict criterion to filter out sites and number of sites remaining at each step. AE, advers events; GFC, geriatric fracture centres; UCC, usual care centres.

Table 1.

Number of selected sites per country

| GFC | UCC | |||

| Country | No of sites | Country | No of sites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matching countries | Australia | 2 | Australia | 1 |

| Austria | 1 | Austria | 1 | |

| China | 1 | China | 1 | |

| India | 2 | India | 2 | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | The Netherlands | 1 | |

| Singapore | 1 | Singapore | 1 | |

| Spain | 3 | Spain | 1 | |

| Thailand | 1 | Thailand | 1 | |

| USA | 2 | USA | 1 | |

| Total | 14 | Total | 10 | |

| Non-matching countries | Argentina | 1 | Canada | 1 |

| Colombia | 2 | Chile | 2 | |

| Czech Republic | 1 | Egypt | 1 | |

| Switzerland | 1 | Nepal | 1 | |

| UK | 1 | Portugal | 1 | |

| Romania | 1 | |||

| Slovenia | 2 | |||

| Venezuela | 1 | |||

| Total | 6 | 10 | ||

GFC, geriatric fracture centres; UCC, usual care centres.

Telephone interview

Finally a total of 22 sites were shortlisted and invited for a telephone interview. As mentioned above, the interview was focused on clarifying questions, confirming or extending further the information provided such as number of patients treated per year or availability of research staff. In the case of sites considered as GFC, the available guidelines and laboratory orders were requested and checked for correspondence with the criteria established in the CIP.

The telephone interview is a good opportunity to get to know the team, particularly in the absence of previous contact with the sites. It is also a good opportunity to ask questions for both sides. For this reason, it was considered important to meet the principal investigator, study coordinator and geriatrician during this call. In one of the sites, only the principal investigator was present, in spite of having confirmed the presence of the whole team. This raised questions regarding the degree of involvement in the study for the rest of the personnel. In another case, discrepancies between the information provided in the REDCap and on the telephone were noted, raising questions about the credibility of the information provided. Challenging clinical research conditions such as high fees and overheads or difficult regulatory conditions were other reasons for elimination at this stage.

Final assessment and selection

Finally, after careful revision of the information provided during the telephone conversation and the guidelines provided by the applicants, sites that did not comply with the criteria for either GFC or UCC were eliminated. The final selection for the GFC study consisted of 12 sites in six countries. No site selection visit was performed to verify the suitability of sites to be part of the GFC study.

Unfortunately, after the contracting process was started, two sites in one country had to be replaced. One site declined due to the workload caused by its participation in the study, which was underestimated by the site itself. The second site was eliminated due to contracting conflicts that were not anticipated during site selection and could not be overcome. Two new sites within the same country were selected instead.

Ethical approval-related and contracting-related issues resulted in delayed start of patient recruitment in 6 of the selected 12 sites. Recruitment period was planned to have a total duration of 16 months to enrol 266 patients (133 patients per group). The first recruited patient was in June 2015 and the target accrual was reached in October 2016; however, the enrolment period was extended for three more months to allow recruitment of at least 20 patients per site. In spite of the delay to open sites for enrolment, patient recruitment went according to expectations (figure 4). The target number of patients per site was 23–25, and most of them reached this recruitment goal (figure 5).

Figure 4.

Patient enrolment until February 2017.

Figure 5.

Patients recruited by study site until February 2017.

Until now, 15 monitoring visits have been done (remote and on-site) and all sites have shown good compliance and high data quality. Of the 282 patients enrolled, no eligibility failures have been detected and so far only 36 patients have dropped out, mainly due to death (24/36). The overall monitoring follow-up rate of the study is defined as the number of visits done divided by the sum of visits due plus visits done (excluding dropouts) and is used as an indicator of quality. For the first study visit at 12 weeks, the overall monitoring follow-up rate of the study is 84% ranging from 50% to 97% depending on the study site. Sites with low follow-up rates might still improve if the reason for the currently missing visits is because the information in the study database has not been updated yet. The GFC study has a large and complex database that collects up to 1484 variables for each patient but notably, our overall response rate to queries is currently 96%.

Discussion

Among other things, the success of a clinical study relies on effective and timely recruitment to avoid delays and added costs.14 15 Poor recruitment is among the leading reasons to discontinue a clinical trial, being cited as the main reason in 10%–29% of studies.16–18 Selecting the appropriate sites to conduct a study is fundamental, and this is why it is extremely important to develop methods to improve the process. The method presented here may serve as a guideline to select sites participating in clinical studies. Even though at first glance, it might seem labour intensive, the effort spent into choosing the best possible clinics will result in a reduction of delays associated with poor site selection such as low recruitment or low data quality.

The purpose of the iterative nature of the process served to identify highly motivated investigators and qualified study sites while quickly narrowing down the number of options. Applicants who fail to fill in questionnaires or to attend a telephone conversation will probably lack the time to screen patients, update the database on a regular basis or answer to queries. In contrast, applicants who showed continued interest arrived to the end of the screening process. In addition, during each step, the number of sites was at least halved and by the end, it was possible to identify a manageable number of promising sites that warranted further evaluation about their feasibility. While the process might seem lengthy, it does not entail an increased burden to the sites and the repeated interactions allow to detect changes of situation or interest during the successive rounds (eg, due to competing trials) as opposed to doing the application and waiting for a long time to the results of the selection.

The next important aspects to take in consideration are the access to the eligible patients, the follow-up rate and the availability of infrastructure or material resources necessary for the study in question. This information is typically asked during feasibility assessments. Templates to prepare site selection questionnaires are very useful to minimise the risk of forgetting important aspects, and they should gather information relative to standard set-up costs (fees for start-up, administration, ethics and governance, overheads etc)14 ethical requirements by local authority, composition of the research team, previous experience and concurrent studies. It is absolutely mandatory to adapt the template to include the assessment of specific aspects of the study, identifying strict requirements from desirable ones.9 13 Strict aspects will become the first focal point for selection at the beginning of the assessment helping to reduce the number of applications rather quickly. Although it was not done for this study, a system that could assign a score or weight to each one of the aspects under evaluation (either strict aspects or desirable ones) could be useful. Site selection visits can be a great added value to assess the site, personnel, infrastructure and accuracy of responses, although it was not performed for this study due to budget constraints.

In order to optimise the site selection process, databases that include information on investigators, sites and patient populations5 19 have been used. This is a good strategy for high incidence diseases such as diabetes, heart failure, cancer, drug addiction, etc. However, the specificities of trauma and diseases in the musculoskeletal field preclude the use of such platforms for our purposes. As our studies require surgical expertise in different areas (trauma, orthopaedics, spine, craniomaxillofacial), we used a growing worldwide network of surgeons to identify skilled specialists with interest in clinical research. Networks can and should be used to raise awareness of ongoing clinical studies. Informing patients about clinical studies is important for recruitment and for this reason, the use of networks as a means of advertisement can enhance participation. When looking for research sites, medical or patient-oriented networks can help to reach interested sites with access to the right patient population.

However, in every network there might be pre-established relationships, so extra care has to be taken to eliminate unintended bias either positive or negative. Favouritism might conduct to the selection of a site that might not be so well suited for the study in question or on the opposite case, to overlook a potentially good site. One way to avoid this would be to perform a blinded review of potential sites by, for example, concealing all the information in the surveys that might make help to identify the site or the investigator.

In all our studies, we search for interested investigators, and they are our main contact; however, the contract is done with their institution. Recently, we have been experiencing increasing difficulties with contracting and negotiations with the legal departments of the sites. It is well known from pharmacological studies nowadays that contracting with a site can take up to 18 months and therefore can cause considerable time delays or even can put the success of the study at risk. In our experience, although rare, the contracting process can extend beyond 1 year. Admittedly this was not addressed sufficiently during our first experience with the new site selection process and has to be improved further to be aware of any upcoming difficulties in contracting as soon as possible. Our results show that this aspect was grossly underestimated. Difficulties in contracting stemmed from objections raised by each legal department in regards to wording, use of terms or internal policies such as refusal to sign a contract redacted in a foreign language. Another reason for failure is that site selection questionnaires are filled in by healthcare professionals who are not well informed about the legal and ethical requirements imposed by their local regulatory authorities. In our case, contractual issues delayed the initiation of some sites and even resulted in the substitution of one of them consequently having additional delays and costs. Despite our best efforts, anticipation of these problems is hardly possible in some cases as there are local differences even within the same country, and clinical studies are evaluated by the ethical committees and contracted on a case-by-case basis. Eliminating sites due to ethical or contracting difficulties has a negative impact on the economic and scientific aspects of the study, but unless there is previous experience with the specific site or the country, certain problems are not foreseeable.

Our first results are very positive as recruitment of the target sample size was achieved according to the planned timelines. The monitoring visits at the sites were encouraging so far, revealing good data quality and motivated site personnel. After this first experience, the same site selection strategy was used for three following studies. The robustness of this method will be determined once further data and experience are available.

In conclusion, our experience with the newly implemented site selection process is promising. It uses networks as means of advertisement, establishment of objective criteria for assessment, a multistep screening process to identify potentially good sites with interest in research, templates tailored to the study requirements and verification of data. Enrolment in sites that were selected with this process is overall satisfying. Difficulties and delays in starting up sites were mainly due to difficulties in site contracting, a topic that should be addressed better during the site selection process in the future. We are confident that the described process improves the site selection and assures a defined quality standard of selected sites. The process appears to be feasible and beneficial for clinical studies within the field of musculoskeletal trauma and diseases, but can be extended to other medical or pharmaceutical areas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the AO Foundation for sponsoring this work and AOCID staff members who have contributed directly or indirectly to this study and in particular to Joffrey Baczkowski for his support and providing relevant data for the development of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: AH-Ch: data collection, manuscript drafting and revision, approval of final manuscript. AJ, DH, MB: conception and design of the study, revision and approval of final manuscript.

Competing interests: AH-Ch, AJ and DH are AOCID employees and receive salary from the AO Foundation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data.

References

- 1. Quintiles. Quintiles Right Start [Webpage]. http://www.quintiles.com/services/quintiles-right-start (cited 27 Apr 2016).

- 2. Goldfarb NM. Trials in the fast lane: “Accelerating clinical trials: budgets, patient recruitment and productivity". J Clin Res Best Pract 2016;1 https://firstclinical.com/journal/2005/0503_Accelerating.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farrell B, Kenyon S, Shakur H, et al. . Managing clinical trials. Trials 2010;11:78 10.1186/1745-6215-11-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gheorghiade M, Vaduganathan M, Greene SJ, et al. . Site selection in global clinical trials in patients hospitalized for heart failure: perceived problems and potential solutions. Heart Fail Rev 2014;19:135–52. 10.1007/s10741-012-9361-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miseta E. Bring Down The Cost Of Clinical Trials With Improved Site Selection: Clinical Leader. 2013. http://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/bring-down-the-cost-of-clinical-trials-with-improved-site-selection-0001?atc~c=771+s=773+r=001+l=a (cited 27 Apr 2013).

- 6. Phillips K. Top 5 Metrics Your Site Should be Using Today Forte Research Systems. 2013. http://forteresearch.com/news/top-5-metrics-your-site-should-be-using-today/ (cited 27 Apr 2016).

- 7. Gehring M, Taylor RS, Mellody M, et al. . Factors influencing clinical trial site selection in Europe: the Survey of Attitudes towards Trial sites in Europe (the SAT-EU Study). BMJ Open 2013;3:e002957 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maskell NA, Jones EL, Davies RJ. Variations in experience in obtaining local ethical approval for participation in a multi-centre study. QJM 2003;96:305–7. 10.1093/qjmed/hcg042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Potter JS, Donovan DM, Weiss RD, et al. . Site selection in community-based clinical trials for substance use disorders: strategies for effective site selection. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2011;37:400–7. 10.3109/00952990.2011.596975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boutron I, Ravaud P, Nizard R. The design and assessment of prospective randomised, controlled trials in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:858–63. 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joeris A, Hurtado-Chong A, Hess D, et al. . Evaluation of the geriatric co-management for patients with fragility fractures of the proximal femur (geriatric fracture center (GFC) concept): protocol for a prospective multicenter cohort study. BMJ Open 2017:e014795 10.1136/bmjopen2016-014795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warden D, Trivedi MH, Greer TL, et al. . Rationale and methods for site selection for a trial using a novel intervention to treat stimulant abuse. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:29–37. 10.1016/j.cct.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berthon-Jones N, Courtney-Vega K, Donaldson A, et al. . Assessing site performance in the Altair study, a multinational clinical trial. Trials 2015;16:138 10.1186/s13063-015-0653-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Treweek S, Mitchell E, Pitkethly M, et al. . Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:MR000013 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasenda B, von Elm E, You J, et al. . Prevalence, characteristics, and publication of discontinued randomized trials. JAMA 2014;311:1045–51. 10.1001/jama.2014.1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bennette CS, Ramsey SD, McDermott CL, et al. . Predicting Low Accrual in the National Cancer Institute's Cooperative Group Clinical Trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108:djv324 10.1093/jnci/djv324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schroen AT, Petroni GR, Wang H, et al. . Achieving sufficient accrual to address the primary endpoint in phase III clinical trials from U.S. Cooperative Oncology Groups. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:256–62. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clinipace. Site selection and Management, 2016. https://www.clinipace.com/site-selection-management/ (cited 27 Apr 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014796supp001.pdf (12.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014796supp002.pdf (20.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014796supp003.pdf (82.9KB, pdf)