Abstract

Objectives

Estimate the prevalence of genital warts (GW) and GW-related healthcare resource use and costs among male and female patients seeking treatment in South Korea.

Design

To estimate GW prevalence, physicians in five major South Korean regions recorded daily logs of patients (n=71 655) seeking care between July 26 and September 27, 2011. Overall prevalence estimates (and 95% CIs) were weighted by the estimated number of physicians in each specialty and the estimated proportion of total patients visiting each specialist type. Healthcare resource use was compared among different specialties. Corresponding p values were calculated using Mann-Whitney U tests.

Setting

The database covers 5098 clinics and hospitals for five major regions in South Korea: Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Gwangju and Daejeon.

Participants

Primary care physicians (general practice/family medicine), obstetricians/gynaecologists, urologists and dermatologists with 2–30 years’ experience.

Results

The estimated overall GW prevalence was 0.7% (95% CI 0.7% to 0.8%). Among women, GW prevalence was 0.6% (95% CI 0.6% to 0.7%); among men prevalence was 1.0% (95% CI 0.9% to 1.0%), peaking among patients aged 18–24 years. Median costs for GW diagnosis and treatment for male patients were US$58.2 (South Korean Won (KRW) ₩66 857) and US$66.3 (KRW₩76 113) for female patients.

Conclusions

The estimated overall GW prevalence in South Korea was 0.7% and was higher for male patients. The overall median costs associated with a GW episode were higher for female patients than for male patients.

Keywords: genital warts, healthcare resource use, south korea

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is novel, due to the limited existing research on genital warts (GW) prevalence and cost in South Korea and the presence of data across multiple physician specialties and geographic regions.

Participating physicians having an increased likelihood to treat patients with GW, possibly resulting in an overestimation of GW in South Korea.

GW prevalence was not estimated from a random sample of physicians. National prevalence estimates were based on the physician population available from the Intercontinental Marketing Services (IMS) database, which may not have included all physicians in South Korea.

Patients with GW who did not seek healthcare treatment were not included.

Potential bias may exist, related to the information source (physician survey), and the direction of bias is unknown.

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are the aetiologic agents of genital warts (GW) and squamous intraepithelial lesions.1 HPV is one of the most frequent sexually transmitted viral infections2 3 and has more than 130 identified virus types.4 HPV 6 and 11 alone are estimated to cause approximately 90% of GW infections.5 GW are highly infectious and nearly 65% of individuals with an infected partner develop lesions within 3 weeks to 8 months from the first contact.3 5 HPV prevalence varies by age and is higher among women and more common for young women with a new sexual partner.6 Research suggests that an estimated 6.2 million new infections occur annually in individuals aged 14–44 years in the USA.

Data on national GW incidence by country are limited, and prevalence estimates by country range widely from 1.4% (Spain)7 to 25.6% (Nigeria).8 9 In a recent systematic review undertaken to determine worldwide GW incidence and prevalence (from published data, January 2001 to January 2012), GW incidence differed in regional distributions from 101 to 205, 118 to 170 and 204 new GW cases per 1 00000 people in North America, Europe and Asia, respectively. Age-specific GW incidence peaked for male patients aged 25–29 years and female patients 20–24 years, and remained significant in patients aged 30–45 years.3

Available GW treatments include patient-applied (home-based) chemicals (podofilox, imiquimod), provider-administered (office-based) chemicals (podophyllin, trichloroacetic acid, interferon) and ablative treatment (cryotherapy, surgery, laser).10 GW treatment and management can result in significant direct and indirect costs, and can cause a considerable financial burden, involving frequent physician office visits, medication application and mechanical removal of warts. A study assessing incidence and economic burden on US commercially insured patients reported estimated costs at $760 per 1000 individuals in the general population in 2004, with total costs exceeding $220 million.11 Another study evaluating the economic burden of GW in Belgium found similar conclusions related to overall costs. The estimated 7989 annual number of patients diagnosed with GW led to an estimated annual cost of €2.53 million.12

To date, there has been little research in South Korea to assess GW incidence and prevalence. A study conducted in South Korea among patients visiting urology (URO) and obstetrics/gynaecology (OB/GYN) clinicians observed a GW prevalence of 0.4% with a higher prevalence among young patients. Among patients with GW, 21% reported to have suffered a GW recurrence.13 As such, the burden of GW may have a larger economic impact on society than previously estimated. Given the lack of available data in South Korea, the current study was designed to estimate GW prevalence in physician practices and GW-related healthcare resource use and costs in South Korea among male and female patients aged 20–60 years.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted via survey in the major regions of South Korea to estimate GW prevalence in physician practices and GW-related healthcare resource use and costs in South Korea among male and female patients. In addition, patients diagnosed with GW were stratified as new, existing, recurrent and resistant cases. The study protocol and list of participating institutions were submitted to the participant hospitals’ Institutional Review Boards. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency, the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) Seoul National University (SNU) Boramae Medical Center and the Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital ethics committees. No confidential patient-level data were collected for this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participating physicians

Participating physicians were identified through the Korean Intercontinental Marketing Services database, which contains nationwide data published by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) Service. The database covers 5098 clinics and hospitals for five targeted specialties in five major regions in South Korea: Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Gwangju and Daejeon. Enrolment in the National Insurance System is mandatory for all clinics and hospitals and is monitored by the HIRA in South Korea. Given the characteristics of the Korean healthcare system, which provides universal coverage, a specific inclusion quota by practice sector (private and public) was not defined. It is assumed that results of treatment pathways, quality, practice of physicians, resources and costs should then be similar for public and private hospitals.

Physicians included in this study: (1) provided informed consent to participate and were specialists, including primary care physicians (PCPs), general practice/family medicine, OB/GYNs, UROs and dermatologists (DERMs) with 2–30 years’ experience; (2) devoted at least 30% of their time seeing and treating patients in outpatient visits, 3 or more work days per week (as opposed to inpatient surgeries, teaching or other activities); (3) treated ≥75 patients in outpatient visits in a typical week and (4) treated ≥50% of patients aged 20–60 years in outpatient visits.

Healthcare costs and resource use

Referral patterns, resource use and costs for patients with GW were captured through a 30 min face-to-face physician survey from July 26, 2011 to September 27, 2011. This survey was conducted after the physicians’ daily logs. The survey included questions related to resource use as part of the usual course of diagnoses, treatment (treatments and procedures performed in-office and topical treatments applied in-office or prescribed at home) and follow-up care (medical visits, emergency room visits, hospitalisations) of typical patients with GW in their practice. Survey questions were included to determine patient referral patterns in the practice, from PCPs to specialists and between specialists. Referral patterns were assessed from the physician survey, including the percentage of patients consulted directly by PCPs, DERMs or UROs and the percentage of patients referred from another physician.

Costs were also reported by physician specialty in 2014 US dollars, converted from the South Korean Won (KRW). The costs per unit of healthcare service were collected from the HIRA Service, and unit cost was applied to the described health resources. For instance, if a particular treatment procedure costs approximately KRW₩100 and on average only 50% of patients actually received that treatment, then the cost for a typical patient would be KRW₩50. Costs were summed across healthcare units to compute the total mean cost of GW for a typical patient.

Statistical analysis

All study outcomes were summarised descriptively. p Values were calculated for comparison between the groups (ie, region, age, sex and physician specialty) using t-tests or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables; χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used for binary or categorical variables.

GW prevalence of new or existing cases was calculated by physician specialty type, based on the number of new or existing cases observed, divided by the total number of patients who were seen during the 2-week study period. Using the national population (18–60 years) 14 and the prevalence of GW in South Korea, the age-adjusted estimate for the number of GW cases in South Korea was projected. Using the distribution of patients with new and existing GW in each age group, the expected number of cases of GW was estimated. The weighted prevalence was calculated based on the proportion of patients with GW at the national level seen by each specialist type, multiplied by the total number of patients in the study and divided by the total number of patients seen by each specific specialty. Prevalence was calculated using normal distribution due to the large number of patients recorded in the daily logs. 15

Prevalence estimates were stratified by age group, sex and physician specialty. Number, mean and 95% CIs were reported. Each physician specialty type reported the number and percentage of new or existing patients with GW. Recurrent and resistant cases for existing patients with GW were also reported.

Results

Prevalence

A total of 200 physicians participated in the study (table 1).

Table 1.

Participating physicians by region and GW cases by speciality in South Korea*

| Participating physicians by region in South Korea | |||||

| Region | PCP (n=50) | DERM (n=35) | OB/GYN (n=65) | URO (n=50) | Overall (n=200) |

| Busan | 6 (12.0%) | 5 (14.3%) | 9 (13.8%) | 9 (18.0%) | 29 (14.5%) |

| Daegu | 3 (6.0%) | 3 (8.6%) | 8 (12.3%) | 7 (14.0%) | 21 (10.5%) |

| Daejeon | 2 (4.0%) | 2 (5.7%) | 5 (7.7%) | 4 (8.0%) | 13 (6.5%) |

| Gwangju | 2 (4.0%) | 3 (8.6%) | 4 (6.2%) | 4 (8.0%) | 13 (6.5%) |

| Seoul | 37 (74.0%) | 22 (62.9%) | 39 (60.0%) | 26 (52.0%) | 124 (62.0%) |

| Total physicians | 50 | 35 | 65 | 50 | 200 |

| GW cases by specialty in South Korea | |||||

| Patients with GW | 7 (0.01%) | 15 (0.1%) | 147 (0.8%) | 133 (0.8%) | 302 |

| New or existing GW | |||||

| New case† | 4 (57.1%) | 6 (40.0%) | 74 (50.3%) | 78 (58.6%) | 163 (53.6%) |

| Existing case‡ | 3 (42.9%) | 9 (60.0%) | 73 (49.7%) | 55 (41.4%) | 140 (46.3%) |

| Valid n patients | 7 | 15 | 147 | 133 | 302 |

| Existing cases | |||||

| Recurrent case§ | 3 (100.0%) | 3 (33.3%) | 43 (58.9%) | 29 (52.7%) | 78 (55.7%) |

| Resistant case¶ | 6 (66.7%) | 30 (41.1%) | 26 (47.3%) | 62 (44.3%) | |

| Total existing patients with GW | 3 | 9 | 73 | 55 | 140 |

*Physician percentages were calculated over the corresponding valid n.

†GW not diagnosed previously by yourself or another physician.

‡GW diagnosed previously by yourself or another physician.

§GW where previous episodes were resolved with treatment.

¶GW where previous episodes were not resolved with treatment.

DERM, dermatologists; GW, genital warts; OB/GYN, obstetricians/gynaecologists; PCP, primary care physicians; URO, urologists.

Regional differences (p<0.05) ranged from a high prevalence of GW in Gwangju followed by Busan. The lowest prevalence was observed in Daejeon (table 2).

Table 2.

GW prevalence among male and female patients in South Korea by region (weighted data)

| Region | All patients* | Average number of patients per physician | Patients with new or existing GW | |

| n | n | n | (%, 95% CI)† | |

| Busan | 11 214 | 387 | 60 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.1) |

| Daegu | 6 773 | 322 | 26 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) |

| Daejeon | 4 078 | 314 | 3 | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) |

| Gwangju | 5 030 | 387 | 44 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) |

| Seoul | 44 560 | 359 | 169 | 0.7 (0.7 to 0.8) |

| Overall | 71 655 | 358 | 302 | 0.8 (0.8 to 0.9) |

*‘All patients’ includes all patients reported for the corresponding region.

†Percentage and 95% CIs were calculated, accounting for the number of patients with identified genital wart status; weighted data.

GW, genital warts.

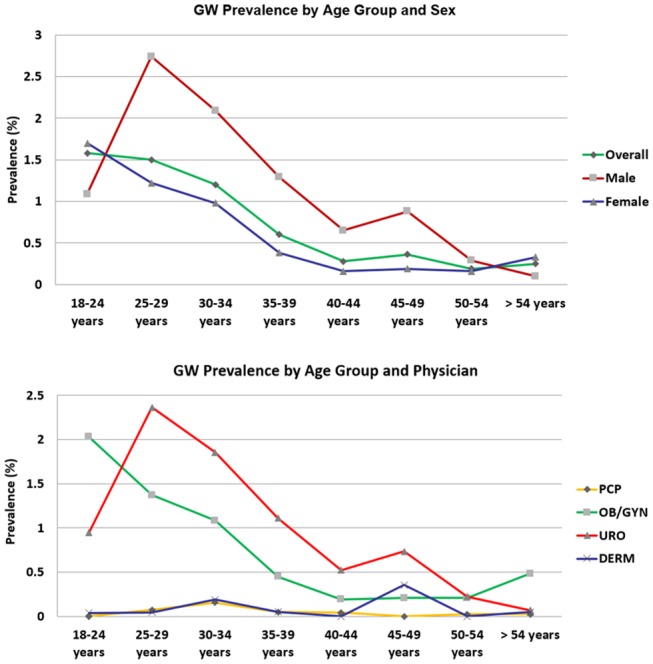

GW prevalence varied by age (figure 1). There was a higher prevalence among men than among women. For men and women, GW prevalence generally decreased as age increased (figure 1). URO and OB/GYN physicians reported a higher prevalence of patients with GW. Few patients with GW were treated by a PCP or DERM (figure 2). The frequency of existing GW was slightly higher among patients treated by a DERM than in the remaining specialties. The percentage of patients who were resistant to GW treatment differed in PCP consultations and DERM consultations (table 1).

Figure 1.

GW prevalence in South Korea. DERM, dermatology; GW, genital warts; OBGYN, obstetrics/gynaecology; PCP, primary care physician; URO, urology.

Figure 2.

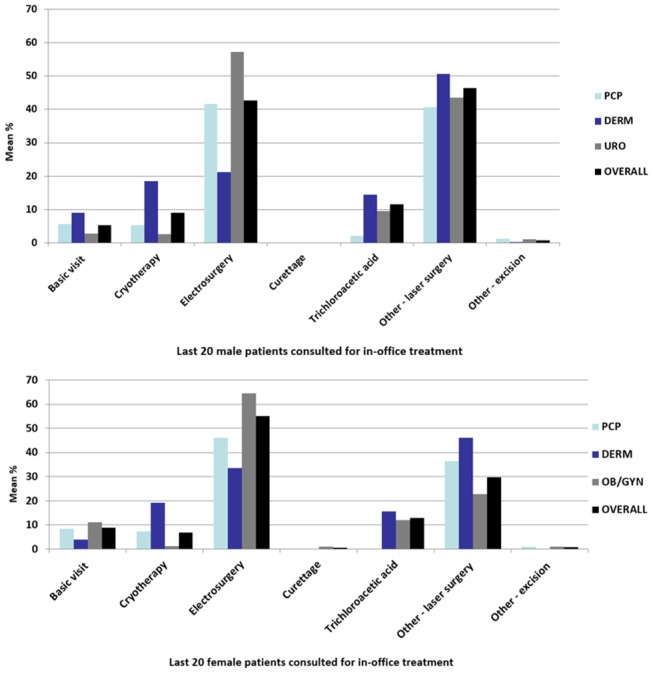

Mean percentage of male and female patients with GW using an in-office treatment or procedure during treatment for GW in South Korea. DERM, dermatology; GW, genital warts; OB/GYN, obstetrics/gynaecology; PCP, primary care physician; URO, urology.

Referral patterns, healthcare resource use and costs

Male patients

Few patients treated by participating physicians were referred by other physicians. The mean number of reported visits was similar across physician specialties (table 3).

Table 3.

Number of office visits during a GW episode and number of hospital and ER visits for male and female patients

| PCP (n=50) | DERM (n=35) | URO (n=50) | Overall (n=85) | p Value | |

| Male patients | |||||

| No of visits | |||||

| Mean (SD) (range) | 2.7 (1.3) (1.0–7.0) | 3.3 (1.7) (1.0–8.0) | 2.6 (1.20) (1.0–6.0) | 2.9 (1.4) (1.0–8.0) | 0.0355* |

| Valid n | 28 | 33 | 49 | 82 | |

| No of hospital or ER visits | |||||

| Mean (SD) (Range) | 0.8 (1.3) (0.0–4.0) | 3.3 (2.1) (0.0–8.0) | 0.4 (1.0) (0.0–5.0) | 0.6 (1.5) (0.0–8.0) | 0.1662* |

| Valid n | 21 | 30 | 46 | 76 | |

| PCP (n=50) | DERM (n=35) | OB/GYN (n=65) | Overall† (n=100) | p Value* | |

| Female patients | |||||

| No of visits | |||||

| Mean (SD) (range) | 3.2 (1.7) (1.0–7.0) | 4.0 (3.5) (1.0–20.0) | 3.7 (1.7) (1.0–10.0) | 3.8 (2.8) (1.0–20.0) | 0.9966* |

| Valid n | 18 | 28 | 65 | 93 | |

| No of hospital or ER visits | |||||

| Mean (SD) (range) | 0.6 (1.2) (0.0–4.0) | 0.9 (1.8) (0.0–5.0) | 0.4 (1.1) (0.0–5.0) | 0.6 (1.4) (0.0–5.0) | 0.1512* |

| Valid n | 14 | 25 | 59 | 84 | |

*Mann-Whitney U test (does not include primary care physician records).

†The overall column does not include primary care physician records.

DERM, dermatology; ER, emergency room; GW, genital warts; OBGYN: obstetrics/gynaecology; PCP, primary care physician; SD, standard deviation;URO, urology

The primary diagnostic technique was visual examination. URO used the HPV PCR test in 12.7% of patients, biopsy in 7.3% and urethroscopy/meatoscopy (depending on the anatomical site) in 3.0%. Based on the feedback from the last 20 male patients with GW, participating physicians reported the use of in-office treatments or procedures. Physicians used laser surgery in 46.4% of patients, followed by electrosurgery (42.5%), trichloroacetic acid (11.5%) and cryotherapy (9.0%). Cryotherapy was more frequently used by DERM (18.5%) than by PCP (5.4%) or URO (2.7%; p<0.001). Electrosurgery was more frequently used by URO (57.2%; p<0.001) than by DERM and PCP. In-office topical medications were administered more often by DERM compared with other physicians, but the differences were not statistically significant (figure 2).

Female patients

The majority of female patients with GW were not referred by another physician. The median number of visits reported was quite similar across physician specialties (table 3). Participating physicians reported the mean in-office diagnostic tools and techniques, treatments or procedures based on the last 20 female patients with GW who sought treatment. Diagnostic tools and techniques used most frequently by physicians to diagnose GW among female patients included visual examination (100% of patients), followed by Pap test (18.4%), biopsy (16%), histological examination (13%), HPV PCR test (11.3%), Hybrid Capture 2 HPV DNA test (8.2%), colposcopy (7.4%) and acetic acid tests (6.7%). There were differences in the use of particular diagnostic tools and techniques. OB/GYN used most of the tests more frequently than DERM, including the Pap smear (26.4%; p<0.001), colposcopy (9.9%; p=0.0430), histological examination (17.5%; p=0.0100), HPV PCR (16.2%; p=0.0010) and Hybrid Capture 2 HPV DNA Test (11.7%; p=0.003).

For female patients with GW, electrosurgery was the most frequently used procedure by all physicians in the office (55.2%), followed by laser surgery (29.8%), trichloroacetic acid (13.0%) and cryotherapy (6.7%). Cryotherapy was administered more frequently by DERM (19.2% of patients) than by PCP (7.2%) or URO (1.2%; p<0.001); electrosurgery was performed more frequently by OB/GYN (64.5%) than by PCP, DERM or URO.

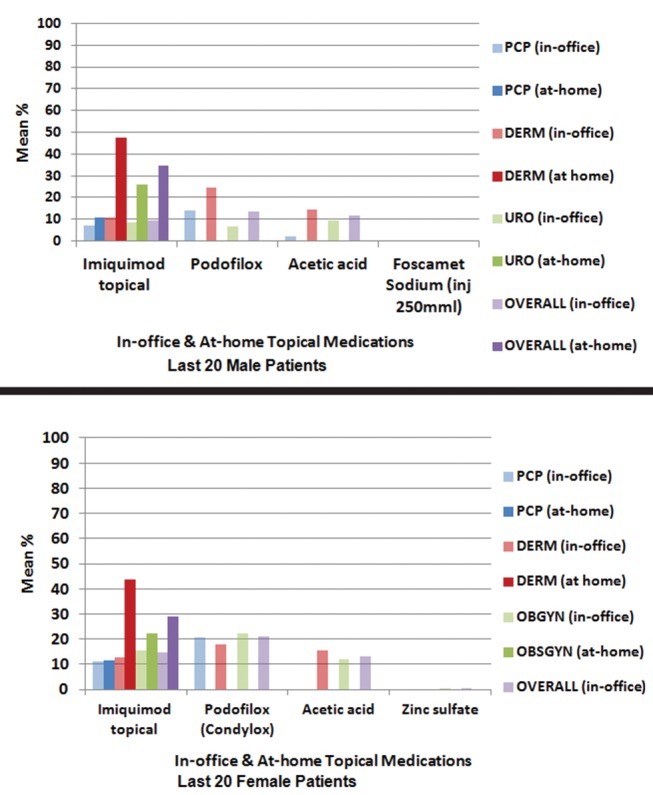

During the course of treatment for a GW episode in female patients, 28.8% were prescribed imiquimod topical (Aldara) as an at-home topical medication (figure 3). Foscarnet sodium injection (250 mL, 500 mL) was not reported as a treatment for female patients with GW, and thus not shown for female patients in figure 3. Imiquimod topical was used more frequently as an at-home medication compared with an in-office medication.

Figure 3.

Mean percentage of patients with GW using both in-office and at-home topical medication during the treatment for GW in South Korea. DERM, dermatology; GW, genital warts; inj: injection; OBGYN, obstetrics/gynaecology; PCP, primary care physician; URO, urology.

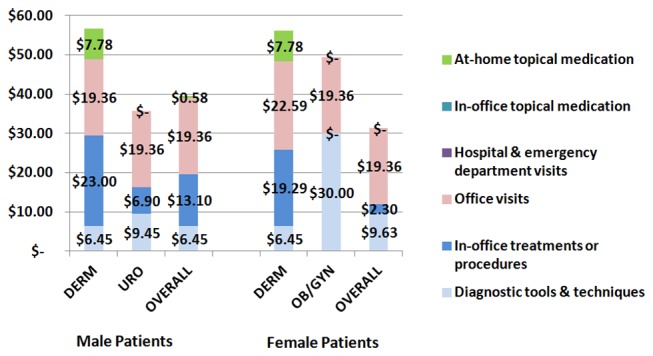

Healthcare costs for male and female patients

Figure 4 shows median costs associated with diagnosis and management of GW in male and female patients. Higher costs were associated with GW in female patients (median costs: US$66.3 (KRW₩76 113) due to the significantly high costs for diagnosis, treatment procedures and at-home medications administered by DERM or OB/GYN, compared with male patients whose median costs for GW were US$58.2 (KRW₩66 857). In addition, statistically significant differences were observed between DERM and URO physicians for overall annual (p values=0.0232), diagnostic tool and technique (p values=0.0033), office visit (p values=0.0355) and at-home topical medication prescription costs (p values=0.0096). Among female patients, the overall annual cost comparison of DERM and OB/GYN practices presented no statistically significant differences (p value=0.5919). However, significant differences by physician specialty for diagnostic tools and techniques (p value <0.0001), in-office treatment and procedure costs (p values=0.0073) and topical medication prescription costs for at-home use (p values=0.0037) were observed.

Figure 4.

Median costs associated with GW diagnosis and treatment in male and female patients. DERM, dermatology; GW, genital warts; OB/GYN, obstetrics/gynaecology; PCP, primary care physician; URO, urology.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study estimated the burden of GW in South Korea by estimating the prevalence of GW and GW-related resource use and costs among male and female patients aged 20–60 years. At the South Korean national level, the current study estimated GW prevalence at 1.0% for male and 0.6% for female patients, which is lower compared with those reported in the USA, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden 16 17 and in other studies conducted in South Korea.18 19 For instance, the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that from 1999 through 2004, 5.6% of survey respondents (aged 18–59 years) self-reported a GW diagnosis.20 The percentage was higher among female patients (7.2%) compared with male patients (4%).19 However, a previous study performed in Hong Kong that used a similar study design estimated an overall GW prevalence rate of 0.9%,21 which is similar to that observed in the current study, which ranged from 0.3% to 1.7% (figure 1).

An earlier Korean study of patients visiting URO and OB/GYN found that the predominant age for those diagnosed with GW was 25–29 years among male patients (prevalence: 1.8%) which is similar to that observed among the male population in our study. Also, in the earlier Korean study, the highest prevalence in the female population was among those aged 30–34 years (prevalence: 0.3%),13 which differs from our study results: The highest prevalence of GW was found among female patients aged 18–24 years (1.2%). A recent US study showed that HPV prevalence was found to be highest among women aged 20–24 years,22 as observed in this study.

Results from a systematic review of GW incidence and prevalence conducted in four Nordic European countries showed a wide range of prevalence in the self-reported history of GW. In surveys of general adult populations, 0.4% (Slovenia, sexually active, aged 18–49 years) to 12.0% (Iceland, aged 18–45 years) of women reported a lifetime history of GW.16 The proportion of GW in male populations varied from 3.6% to 7.9% in Australia, Denmark, United Kingdom and USA, and was 0.3% in Slovenia, from November 2004 to June 2005.20 Also, results from a recent study of the Czech Republic population showed rising incidence of GW, with a 5.8% prevalence rate among patients aged 16–55 years.23

Differences in sexual behaviour and use of different case ascertainment methods for GW-related data may explain differences in prevalence found in these European studies compared with South Korea. In South Korea, the average age of a woman’s first sexual intercourse experience is approximately 20 years,24 compared with 16 years in the European studies. In the Kjaer et al study,16 GW prevalence was calculated using self-reported data, while in the current study, only patients seeking healthcare were included. Therefore, the burden of GW results may have been higher due to those not seeking treatment or unreported cases.

In Australia, Pirotta et al estimated an annual incidence rate of 2.2 cases of GW per 1000 Australians, with peak incidence in women aged 20–24 years, at 8.6 cases per 1000, and in men aged 25–29 years, at 7.4 cases per 1,000.25 In the USA, a study by Hoy et al found that GW incidence was highest among women aged 20–24 (4.6/1,000) and men aged 25–29 (2.7/1,000) in 2004.11 Similarly, a study conducted in Canada found that overall GW prevalence between 1998 and 2006 was higher among men than women. Data from 2006 showed that prevalence was highest among women aged 20–24 years (3.9/1,000), whereas in men, the prevalence peaked at age 25–29 years (3.7/1,000).26

The most common treatment options for GW are podofilox, imiquimod, surgical excision and cryotherapy.27 In the current study, electrosurgery was the most frequently used therapy, followed by pharmacological topical treatments in the office and at home and other surgical procedures.

In-office treatment for GW varied by physician specialty. Cryotherapy was more frequently administered by DERM than by other specialists, possibly because of expertise and access to equipment. Likewise, electrosurgery was more frequently used by URO and DERM than by PCP and OB/GYN. Imiquimod was the topical medication of choice for treatment of GW. As expected, patient referral to specialists was higher for PCP, who referred most men to URO and most women to OB/GYN. Specialists also referred patients to physicians within the same specialty (eg, DERM referred to another DERM, and so on.).

GW diagnosis and treatment for male patients was associated with overall median costs of US$58.2 (KRW₩66 857) and US$66.3 (KRW₩76 113) for female patients. For male patients, the highest overall costs were due to office visits (49.0%), followed by in-office treatments and procedures (33.2%) and diagnostic tools and techniques (16.3%). For female patients, most costs were related to office visits (61.9%), followed by diagnostic tools and techniques (30.8%) and in-office topical medications (7.4%).

USA,28 Italy29 and Canada25 have conducted considerable research on GW-related healthcare costs. A Canadian claims data study found that the average cost per GW episode was CaD$190 (male: $C176; female: $C207).25 However, this Canadian study is not comparable with this current study given the socioeconomic and healthcare system differences between the two countries. A more analogous study methodology and design for cost estimation was conducted in Australian sexual health clinics by Pirotta et al. This study showed that higher costs were associated with GW among women ($A386) as compared with men ($A251), similar to the trends found in the current study.24 Two hundred physicians and 71 655 patients with GW were included in the study from five regions in South Korea. However, it is possible that the sample may not show a complete representation of the entire population of patients with GW who sought treatment.

Limitations

The selection of participating specialities and the physicians of each specialty are important study limitations, as their patients may not be representative of the entire population of patients who sought treatment. Participating specialists were selected in order to include patients with a diagnosis of GW in South Korea. A low rate of bias was expected to be associated with this factor. The expectation was that a lower percentage of patients would be treated by other specialists than those included in the study. Participating physicians were selected, accounting for different regions, in order to include results of regional differences in GW prevalence. The fact that there was major participation of physicians working in the private sector and not in the public sector is another limitation of this study. Nevertheless, the Korean Healthcare System implements universal health insurance coverage; therefore, the National Health Insurance Program in South Korea is a compulsory social insurance covering the entire population. It may be assumed that treatment quality, physician practice costs and reimbursements were similar in public and private hospitals and clinics. Any bias associated with the profile of participating physicians in terms of private and public sector was expected to be minimal.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TSL, SKT, PKS, KY, AK, ARG, SMG, WJ, NL and MR conceived and designed the experiments for this manuscript.

NL, MR, SKT, PKS and AK performed the experiments for this manuscript.

NL and MR analysed the data for this manuscript.

NL and MR contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools for this manuscript.

All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Merck & Co.

Competing interests: TSL has no conflicts to declare. KY was a paid contractor for Merck & Co. at the time of the study, and was an employee of Cubist Pharmaceuticals from December 2014 to July 2015, which was acquired by Merck & Co. in January 2015. AK, SKT and PKS are employees of Merck & Co. SMG received grants to her institution from the Commonwealth Department of Health for human papillomavirus (HPV) genoprevalance surveillance post-vaccination, Merck & Co. and GSK to perform phase 3 clinical vaccine trials: Merck to evaluate HPV in r post-vaccination programme; Commonwealth Serum Laboratories for HPV in cervical cancer study and Veterinary Centers of America for a study on the effectiveness of a public health HPV vaccine study and a study on the associations of early onset cancers. SMG received speaking fees from Merck Sharp and Dohme and Sanofi Pasteur / Merck Sharp and Dohme for work performed in her personal time. Merck & Co. paid for travel and accommodation to present at HPV Advisory board meetings. ARG is a member of Merck & Co., Inc. advisory boards. Her institution has received grants and contracts to support HPV-related research. NL and MR are employees of IMS Health, Barcelona, Spain, which is a paid consultant to Merck & Co. WJ has no conflicts to declare.

Patient consent: Our study uses secondary data collected from surveyed physicians. Patient consent would be obtained at the physician level. Patient data were deidentified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

Ethics approval: National Evidence-based Health Care Collaborating Agency (NECA), the SMG-SNU University Medical Center and the Ewha Woman's University Mokdong Hospital ethics committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data collected are the property of Merck & Co., Inc. and can be accessed with permission from Merck & Co., Inc.

References

- 1. Winer RL, Lee SK, Hughes JP, et al. . Genital human papillomavirus infection: incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university students. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:218–26. 10.1093/aje/kwf180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arima Y, Winer RL, Feng Q, et al. . Development of genital warts after incident detection of human papillomavirus infection in young men. J Infect Dis 2010;202:1181–4. 10.1086/656368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pirotta MV, Stein AN, Fairley CK, et al. . Patterns of treatment of external genital warts in australian sexual health clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:375–9. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181971e4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haupt RM, Sings HL. The efficacy and safety of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus 6/11/16/18 vaccine gardasil. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:467–75. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Garland SM, Steben M, Sings HL, et al. . Natural history of genital warts: analysis of the placebo arm of 2 randomized phase III trials of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine. J Infect Dis 2009;199:805–14. 10.1086/597071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raymakers AJ, Sadatsafavi M, Marra F, et al. . Economic and humanistic burden of external genital warts. Pharmacoeconomics 2012;30:1–16. 10.2165/11591170-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castellsagué X, Cohet C, Puig-Tintoré LM, et al. . Epidemiology and cost of treatment of genital warts in Spain. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:106–10. 10.1093/eurpub/ckn127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Graziottin A, Serafini A. HPV infection in women: psychosexual impact of genital warts and intraepithelial lesions. J Sex Med 2009;6:633–45. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01151.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clifford GM, Gallus S, Herrero R, et al. . Worldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: a pooled analysis. Lancet 2005;366:991–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67069-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs): genital herpes treatment and care http://www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/treatment.htm (accessed 26 June 2013).

- 11. Hoy T, Singhal PK, Willey VJ, et al. . Assessing incidence and economic burden of genital warts with data from a US commercially insured population. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2343–51. 10.1185/03007990903136378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Annemans L, Rémy V, Lamure E, et al. . Economic burden associated with the management of cervical Cancer, cervical dysplasia and genital warts in Belgium. J Med Econ 2008;11:135–50. 10.3111/13696990801961611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee CB, Choe HS, Hwang SJ, et al. . Epidemiological characteristics of genital herpes and condyloma acuminata in patients presenting to urologic and gynecologic clinics in Korea. J Infect Chemother 2011;17:351–7. 10.1007/s10156-010-0122-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Statistics Korea. http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/index.action accessed 1 Mar 2013.

- 15. Brown LD, Cai TT, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci 2001;16:101–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunne EF, Nielson CM, Stone KM, et al. . Prevalence of HPV infection among men: a systematic review of the literature. J Infect Dis 2006;194:1044–57. 10.1086/507432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kjaer SK, Tran TN, Sparen P, et al. . The burden of genital warts: a study of nearly 70,000 women from the general female population in the 4 nordic countries. J Infect Dis 2007;196:1447–54. 10.1086/522863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shin HR, Franceschi S, Vaccarella S, et al. . Prevalence and determinants of genital infection with papillomavirus, in female and male university students in Busan, South Korea. J Infect Dis 2004;190:468–76. 10.1086/421279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim MA, Oh JK, Kim BW, et al. . Prevalence and seroprevalence of low-risk human papillomavirus in korean women. J Korean Med Sci 2012;27:922–8. 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.8.922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dinh TH, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, et al. . Genital warts among 18- to 59-year-olds in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999--2004. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:357–60. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181632d61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin C, Lau JT, Ho KM, Km H, et al. . Incidence of genital warts among the Hong Kong general adult population. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:272 10.1186/1471-2334-10-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dunne EF, Sternberg M, Markowitz LE, et al. . Human papillomavirus (HPV) 6, 11, 16, and 18 prevalence among females in the United States--National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006: opportunity to measure HPV vaccine impact? J Infect Dis 2011;204:562–5. 10.1093/infdis/jir342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petráš M, Adámková V. Rates and predictors of genital warts burden in the czech population. Int J Infect Dis 2015;35:29–33. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kang HS, Moneyham L. Attitudes toward and intention to receive the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination and intention to use condoms among female korean college students. Vaccine 2010;28:811–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pirotta M, Stein AN, Conway EL, et al. . Genital warts incidence and healthcare resource utilisation in Australia. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:181–6. 10.1136/sti.2009.040188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marra F, Ogilvie G, Colley L, et al. . Epidemiology and costs associated with genital warts in Canada. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:111–5. 10.1136/sti.2008.030999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kodner CM, Nasraty S. Management of genital warts. Am Fam Physician 2004;70:2335–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Insinga RP, Dasbach EJ, Myers ER. The health and economic burden of genital warts in a set of private health plans in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:1397–403. 10.1086/375074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Merito M, Largeron N, Cohet C, et al. . Treatment patterns and associated costs for genital warts in Italy. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3175–83. 10.1185/03007990802485694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.