Abstract

Objective

To assess incidence of condyloma after two doses of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (qHPV) vaccine, by time since first vaccine dose, in girls and women initiating vaccination before age 20 years.

Design

Register-based nationwide open cohort study.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

Girls and women initiating qHPV vaccination before age 20 years between 2006 and 2012. The study cohort included 264 498 girls, of whom 72 042 had received two doses of qHPV vaccine and 185 456 had received all three doses.

Main outcome measure

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of condyloma estimated by time between first and second doses of qHPV in months (m) and age at vaccination, adjusted for attained age.

Results

For girls first vaccinated with two doses before the age of 17 years, the IRR of condyloma for 0–3 months between the first and second doses was 1.96 (95% CI 1.43 to 2.68) as compared with the standard three-dose schedule. The IRRs were 1.27 (95% CI 0.63 to 2.58) and 4.36 (95% CI 2.05 to 9.28) after receipt of two doses with 4–7 months and 8+ months between doses, respectively. For women first vaccinated after the age of 17 years, vaccination with two doses of qHPV vaccine and 0–3 months between doses was associated with an IRR of 2.12 (95% CI 1.62 to 2.77). For an interval of 4–7 months between doses, the IRR did not statistically significantly differ to the standard three-dose schedule (IRR=0.81, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.84). For women with 8+ months between dose 1 and dose 2 the IRR was 3.16 (95% CI 1.40 to 7.14).

Conclusion

A two-dose schedule for qHPV vaccine with 4–7 months between the first and second doses may be as effective against condyloma in girls and women initiating vaccination under 20 years as a three-dose schedule. Results from this nationwide study support immunogenicity data from clinical trials.

Keywords: epidemiology, preventive medicine, public health, infectious diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We were able to link vaccination status to disease outcome on an individual level through use of high-quality national register-based data.

Observation studies such as this are able to look at the pragmatic effectiveness of vaccination in a large population.

We did not look at HPV disease outcomes other than condyloma.

The majority of girls and women in the cohort had 0–3 months between first and second doses, which limited the power for other exposure groups in our study.

A small proportion of condyloma cases may have been missed, as some patients will neither seek hospital care for condyloma nor receive prescription for treatment, and thus will not be included in the registers.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are subunit vaccines containing virus-like particles, and typically require multiple doses to confer an immune response,1 therefore, a three-dose schedule (0, 2, 6 months) was initially approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). As the immune response has been shown to be stronger in young girls 9–14 years of age compared with women 15–25 years of age, recommendations to reduce the number of doses to two have been put forward for the younger age groups, provided doses are optimally spaced.2–6 Thus, in 2014, HPV vaccines were licensed in a two-dose schedule for girls aged between 9 years to 14 years with doses at 0 months and 6 months.7 8

In Sweden, HPV vaccination was originally introduced as part of a subsidised three-dose schedule in 2007 for girls and women aged 13–17 years. Other ages could still be vaccinated, but were required to pay the full cost of the vaccine. In 2012, an organised national programme was initiated, with girls aged 10–12 years routinely vaccinated as part of the childhood vaccination programme. Catch-up vaccinations were offered to girls aged 13–18 years. In January 2015, a two-dose schedule for girls aged 10–13 years was implemented.

Several potential benefits may be conferred by such a reduced dosing schedule, including increased compliance, lower programme costs and improved logistics. However, the recommendation for a two-dose schedule was based on immunogenicity results and does not take into account the antibody threshold at which HPV diseases may be prevented—a threshold that has yet to be identified.9 Therefore, observational studies are necessary to ascertain effects of dose alterations in HPV vaccination on clinical end points. The use of condyloma as a marker for vaccine effectiveness is in this context timely, due to its considerably shorter latency period than precancerous cervical lesions and cancer. We here investigate whether optimal timing of two doses of qHPV vaccine could confer the same level of protection against condyloma as a standard three-dose schedule on a population level in Sweden.

Methods

Study population

This study was a nationwide open cohort of girls and young women aged 10–27 years and registered as living in Sweden between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2012. Subjects entered the study cohort on the date of administration of the second dose of qHPV vaccine and were followed up for first occurrence of condyloma. The cohort of girls was sampled prior to the implementation of the two-dose schedule in Sweden, that is, girls and women were sampled during a three-dose schedule period.

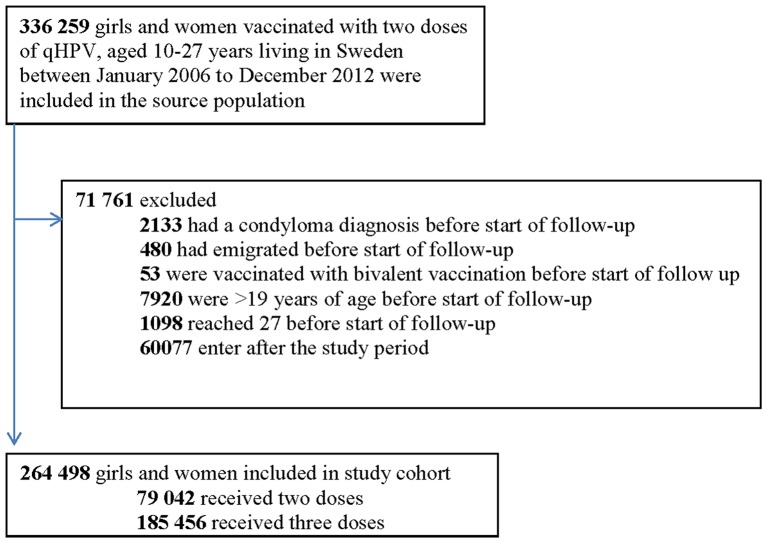

To ensure only incident condyloma infection was measured, all individuals with condyloma diagnosis prior to follow-up were excluded, as were individuals who emigrated or received bivalent HPV vaccine before follow-up. Women that initiated qHPV vaccination over the age of 20 years or turned 27 years of age before the start of follow-up were also excluded (figure 1). Women were censored during follow-up if they died (n=58), received a condyloma diagnosis (n=619), emigrated (n=1037), were not resident in Sweden (n=4) or received the bivalent HPV vaccine (n=38).

Figure 1.

Details on study exclusions and the population analysed to investigate timing of two versus three doses of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and associated effectiveness against condyloma.

Data sources

Data were collected using the Swedish national population registers and linked through use of unique personal identification numbers.10 The Swedish HPV Vaccination Register (SVEVAC), a voluntary national HPV vaccination register initiated in 2006, was used for information on HPV vaccination exposure. Timing between doses was calculated using data from this register. In addition to SVEVAC, data were also collected from the Prescribed Drug Register (PDR), which contains information on all prescriptions handled at Swedish pharmacies since July 2005. The Patient Register and PDR were used to extract information on condyloma outcomes. The Patient Register contains data regarding all inpatient and outpatient visits in Swedish hospitals and specialist care since 1987 and 2001, respectively. Information regarding deaths was collected from the Cause of Death Register and emigration status was collected from the Migration Register. Parents were identified from the Multigeneration Register and their highest education level nearest to the date of entry, as a proxy for socioeconomic status, was identified from the Education Register.

Case definition

Condyloma cases were defined as a first diagnosis of condyloma in the Patient Register or a prescription for condyloma-specific treatments in the PDR. In the Patient Register, all women that received a main or secondary diagnosis of condyloma were identified using the ICD10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) code A63.0.11 In the PDR, all women who received podophyllotoxin and imiquimod were identified using Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical Codes (ATC) D06BB04 and D06BB10, respectively.12

Vaccination status

SVEVAC was used to obtain bivalent HPV and qHPV vaccination dates and was complemented with prescription data collected from the PDR, using ATC codes J07BM01 and J07BM02, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Crude incidence rates (IRs) per 100 000 person-years were calculated as the number of cases of condyloma per accrued person-time, stratified by the time interval between first and second doses (0–3 months, 4–7 months or 8+ months). As we have previously shown an effect of age at vaccination on vaccine effectiveness,12 13 girls and women were grouped into two age-at-first-vaccination categories (10–16 years and 17–19 years), a divide reflecting the median age for sexual debut in Sweden at 16.5 years.14

Poisson regression was used to model IRs by time between first and second doses and age at first vaccination and adjusted for attained age. The time scale for individual follow-up was attained age, which was split into five intervals (10–13 years, 14–16 years, 17–19 years, 20–21 years and 22+ years), to reflect increasing risk of infection and disease with increasing age. Vaccine dosage (three doses vs two doses) was handled as a time-varying exposure, so that women could contribute person-time to both dose categories. The effect of time between doses was allowed to vary by age at first vaccination via an interaction term. This model was then used to estimate IR ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs after two doses of qHPV relative to three sets of reference groups: First, compared with women who had initiated vaccination at the same age and had received three doses of qHPV (0 months, 2 months and 6 months); these IRRs measure effectiveness of a two-dose schedule with different timings between dose 1 and dose 2 relative to a standard three-dose schedule. Second, compared with women who had initiated vaccination at the same age and had received three doses of qHPV with the same timing between first and second doses (two doses with 0–3 months vs three doses with 0–3 months, etc.); this matched comparison addresses the question of how much extra protection is gained on average by a third dose for different timings for the first two. Third, compared with women who had initiated vaccination at the same age and had received three doses of qHPV with no restriction on the time between dose 1 and dose 2 or dose 2 and dose 3e; these IRRs measure effectiveness of a two-dose schedule relative to a pragmatic three-dose schedule. IRs and IR differences (IRDs) with corresponding 95% CIs predicted by the models and averaged across levels of attained age in the study cohort were also reported. Furthermore, two sensitivity analyses were carried out. First, to determine whether socioeconomic status was a confounder in our study, and second, a sensitivity analysis restricting the time between dose 1 and dose 2 to 12 months, were conducted.

Results

Study cohort

At the end of the study period 264 498 girls under the age of 20 years were vaccinated with at least two doses of qHPV. Of these, 79 042 (29.9%) received only two doses of qHPV vaccine and 185 456 (70.1%) received all three doses. The majority (n=1 54 440, 83.3%) of the individuals fully vaccinated followed the recommended dosing schedule given at 0 months, 2 months and 6 months. Median time in follow-up was 259 days (IQR 186–1271 days).

Crude IRs

For girls initiating vaccination with qHPV before 17 years the IR after vaccination with two doses was 84 (95% CI 66 to 108), 95 (95% CI 48 to 190), and 351 (95% CI 168 to 737) per 100 000 person-years, when there were 0–3 months, 4–7 months and 8+ months between doses 1 and 2, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Number of individuals, cases, person-years and crude incidence rate (IR) by age at vaccination initiation and time between doses 1 and 2

| Age at first vaccination | Number of doses | Time between doses 1 and 2 (months) | Individuals (n) | Condyloma cases (n) | Person-years | Crude IR, (95% CI)* |

| ≤16 years | Two doses | 0–3 | 2 04 103 | 63 | 74 611 | 84 (66; 108) |

| 4–7 | 8095 | 8 | 8404 | 95 (48; 190) | ||

| 8+ | 1894 | 7 | 1992 | 351 (168; 737) | ||

| Three doses | 0–3 | 1 42 046 | 222 | 2 75 495 | 81 (71; 92) | |

| 4–7 | 2803 | 8 | 6619 | 121 (60; 242) | ||

| 8+ | 919 | 2 | 1646 | 121 (30; 486) | ||

| Standard dosing schedule (0, 2, 6) | 1 22 425 | 182 | 2 31 393 | 79 (68; 91) | ||

| 17–19 years | Two doses | 0–3 | 46 712 | 97 | 23 750 | 408 (335; 498) |

| 4–7 | 2965 | 6 | 3886 | 154 (69; 344) | ||

| 8+ | 615 | 6 | 995 | 603 (271; 1343) | ||

| Three doses | 0–3 | 38 705 | 197 | 93 908 | 210 (182; 241) | |

| 4–7 | 808 | 3 | 2087 | 144 (46; 446) | ||

| 8+ | 175 | 0 | 365 | - | ||

| Standard dosing schedule (0, 2, 6) | 32 015 | 146 | 76 168 | 192 (163; 225) |

*IR reported per 100 000 person-years

Condyloma incidence after two-dose vaccination was higher in girls initiating vaccination after 17 years of age, with IRs of 408 (95% CI 335 to 498), 154 (95% CI 69 to 344) and 603 (95% CI 271 to 1343) per 100 000, when there were 0–3 months, 4–7 months and 8+ months between dose 1 and 2, respectively (table 1).

IRRs comparing two doses versus standard three-dose vaccination

For girls initiating vaccination before the age of 17 years there was a statistically significantly increased risk for condyloma when comparing two-dose vaccination 0–3 months apart (IRR=1.96, 95% CI 1.44 to 2.68) and 8+ months apart (IRR=4.36, 95% CI 2.05 to 9.28) to a standard three-dose schedule. No statistically significant association (IRR=1.27, 95% CI 0.63 to 2.58) was found after vaccination with two doses given 4–7 months apart. The IRDs predicted by the model were 59 (95% CI 25 to 92), 17 (95% CI −38 to 71) and 205 (95% CI 8 to 402) extra cases per 100 000 person-years for 0–3 months, 4–7 months and 8+ months between doses 1 and 2, respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

IR, IRR and IRD comparing two-dose versus three-dose vaccination by age at vaccination initiation and time between dose 1 and dose 2, adjusted for attained age

| Age at first vaccination | Number of doses | Time between dose 1 and dose 2 (months) | IR, 95% CI* | p Value | IRR, 95% CI | p Value | IRD, 95% CI* | p Value |

| ≤16 years | Three doses | Standard dosing schedule (0, 2, 6) | 61 (52; 70) | <0.001 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 0–3 | 119 (88; 151) | <0.001 | 1.96 (1.44; 2.68) | <0.001 | 59 (25; 92) | 0.001 | |

| 4–7 | 77 (24; 131) | 0.005 | 1.27 (0.63; 2.58) | 0.506 | 17 (−38; 71) | 0.551 | ||

| 8+ | 265 (68; 462) | 0.008 | 4.36 (2.05; 9.28) | <0.001 | 205 (8; 402) | 0.042 | ||

| 17–19 years | Three doses | Standard dosing schedule (0, 2, 6) | 113 (90; 135) | <0.001 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 0–3 | 239 (187; 291) | <0.001 | 2.12 (1.62; 2.77) | <0.001 | 126 (73; 179) | <0.001 | |

| 4–7 | 91 (18; 165) | 0.015 | 0.81 (0.36; 1.84) | 0.615 | −21 (−97; 54) | 0.580 | ||

| 8+ | 355 (68; 643) | 0.015 | 3.16 (1.40; 7.14) | 0.006 | 243 (44; 530) | 0.097 |

*IR, IRD reported per 100 000 person-years. Reference groups: ≤16 years with three doses of qHPV (0 months, 2 months, 6 months) and 17–19 years with three doses of qHPV (0 months, 2 months, 6 months)

IR, incidence rate; IRD, incidence rate difference; IRR, incidence rate ratio; qHPV, quadrivalent human papillomavirus.

A similar pattern is seen in girls and women initiating vaccination after turning 17 years, with increased risks for condyloma after two doses if given 0–3 months (IRR=2.12, 95% CI 1.62 to 2.77) or 8+ months (IRR=3.16, 95% CI 1.40 to 7.14) apart. No association was found when comparing two doses versus three doses with 4–7 months between dose 1 and dose 2 (IRR=0.81, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.84) (table 2).

The first sensitivity analysis including socioeconomic status revealed no significant change to the point estimates (see supplementary 1). In the second sensitivity analysis the IRRs were comparable, therefore the cut-off at 12 months was not applied (data not shown).

bmjopen-2016-015021supp001.docx (15.9KB, docx)

IRRs comparing two-dose versus matched three-dose vaccinations

Comparing two-dose vaccination, 0–3 months apart, versus three-dose vaccination with 0–3 months between doses 1 and 2, results remained effectively unchanged both for girls initiating vaccination prior to age 17 years (IRR=1.95, 95% CI 1.44 to 2.64) and girls initiating vaccination between 17 years and 19 years (IRR=1.88, 96% CI 1.46 to 2.42) (table 3).

Table 3.

IR, IRR and IRD comparing two-dose vaccination with varying time between doses 1 and 2 versus three-dose vaccination by age at vaccination initiation, adjusted for attained age

| Age at first vaccination | Number of doses | Time between dose 1 and dose 2 (months) | IR, 95% CI* | p Value | IRR, 95% CI | p Value | IRD, 95% CI* | p Value |

| ≤16 years | Three doses | 0–3 | 63 (55; 72) | <0.001 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 0–3 | 123 (90; 156) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.44; 2.64) | <0.001 | 60 (26; 94) | <0.001 | |

| ≤16 years | Three doses | 4–7 | 91 (28; 154) | 0.005 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 4–7 | 79 (24; 133) | 0.005 | 0.87 (0.33; 2.32) | 0.779 | −12 (−95; 71) | 0.779 | |

| ≤16 years | Three doses | 8+ | 86 (−33; 205) | 0.158 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 8+ | 270 (70; 470) | 0.008 | 3.14 (0.65; 15.09) | 0.154 | 184 (−49; 417) | 0.122 | |

| 17–19 years | Three doses | 0–3 | 129 (107; 150) | <0.001 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 0–3 | 242 (190; 294) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.46; 2.42) | <0.001 | 114 (60; 167) | <0.001 | |

| 17–19 years | Three doses | 4–7 | 88 (−12; 189) | 0.084 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 4–7 | 95 (19; 172) | 0.015 | 1.08 (0.27; 4.31) | 0.916 | 7 (−119; 133) | 0.915 | |

| 17–19 years | Three doses | 8+ | 0 | - | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Two doses | 8+ | 373 (72; 675) | 0.015 | - | - | 373 (72; 675) | 0.015 |

*IR, IRD reported per 100 000 person-years. Matched reference groups: ≤16 years with three doses of qHPV with 0–3 months between dose 1 and dose 2, ≤16 years with three doses of qHPV with 4–7 months between dose 1 and dose 2 and ≤16 years with three doses of qHPV with 8+ months between dose 1 and dose 2; 17–19 years with three doses of qHPV with 0–3 months between dose 1 and dose 2, 17–19 years with three doses of qHPV with 4–7 months between dose 1 and dose 2 and 17–19 years with three doses of qHPV with 8+ months between dose 1 and dose 2.

IR, incidence rate; IRD, incidence rate difference; IRR, incidence rate ratio; qHPV, quadrivalent human papillomavirus.

Comparing two-dose versus three-dose vaccinations with 4–7 months and 8+ months between the first two doses for both schedules, we found non-significant associations with IRRs of 0.87 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.32) and 3.14 (95% CI 0.65 to 15.09), respectively, for girls initiating vaccination prior to 17 years, with corresponding IRDs of −12 (95% CI −95 to 71) and 184 (95% CI -49 to 417) cases per 100 000 person-years (table 3). For girls initiating vaccination between 17 years and 19 years, no association was found for 4–7 months in between doses (IRR=1.08, 95% CI 0.27 to 4.31); no cases of condyloma were reported in fully vaccinated women initiating vaccination between 17 years and 19 years (table 3).

IRRs comparing two doses versus pragmatic three-dose vaccination

Changing the reference group to pragmatic three-dose vaccination did not materially affect the results. (see supplementary table 2).

bmjopen-2016-015021supp002.pdf (70.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

Statement of principle findings

This population-based study investigates the incidence of condyloma after two doses of qHPV by time between first and second doses. Our results suggest that a two-dose regimen is similarly effective as a standard three-dose schedule if given 4–7 months apart. This is in line with the recommendations from the EMA and the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts and immunological results from clinical trials.2 3 5 6 15–19

In relation to other studies

The impact of HPV vaccines was first recognised for HPV infections, and HPV-related diseases with short incubation times following infection such as genital warts.20 Studies have shown that three-dose schedules of qHPV vaccination have been effective in the prevention of genital warts at a population level.21–24 In addition, observational studies assessing the effectiveness of qHPV against cervical abnormalities have been carried out.25–28 A recent review by Garland et al suggested that in successive birth cohorts that are beginning screening, there have been reductions in the number of low-grade cytological abnormalities and high-grade histology confirmed cervical lesions (approximately 45% and 85%, respectively).29

Alternative dosing schedules on condyloma incidence have been investigated in Denmark and Sweden,9 13 with both studies showing that condyloma incidence was statistically significantly higher in women aged 19–24 years after two doses rather than three. However, receipt of two vaccine doses with optimum interval was reported as non-inferior to three doses in terms of condyloma reduction, a finding with which the present study concurs.

Strengths and weaknesses

This was a nationwide study including the entire vaccinated Swedish female population aged 10–27 years. The use of high-quality national register-based data meant that we were able to link vaccination status to disease outcome on an individual level.

A limitation of our study is that a small proportion of patients will neither seek hospital care for condyloma nor receive prescription for treatment, and thus will not be included in the registers, resulting in an underestimation of the true number of condyloma cases.12 However, we expect this to be negligible in our study, as (A) vaccinated women have been found to have higher screening uptake than unvaccinated women and can thus also be assumed not to be less prone to access healthcare30 and (B) the estimated effect of the two-dose schedule would only be inflated if girls less willing to complete the three-dose schedule would have been more likely to seek healthcare for condyloma than those going on to complete three doses.

Another potential limitation is that SVEVAC was a voluntary register for the period 2006–2010, with only 80%–85% coverage. To avoid an underestimation of vaccination exposure, we complemented missing data using the PDR. This method has been used previously in a study by Herweijer et al, who found unique vaccination dose dates for 99.6% of the vaccinated girls and women in the cohort.13

It is also possible that individuals might have a prevalent HPV infection at the time of vaccination, resulting in an underestimation of protective effect of the vaccine. We have attempted to control for this by excluding women who had a history of condyloma before the start of individual follow-up. Additionally, given that we start follow-up for condyloma incidence only after the second dose, we have the automatic benefit of a buffer period as used in a previous study conducted by Herweijer et al.13

It is also of note that the majority of women in the cohort had 0–3 months between the first and second doses, which limited the power for other exposure groups in our study and resulted in wider CIs, particularly in comparisons with the older age group and increasing time between doses. While we did not find socioeconomic status as a confounder in our study and we hypothesise that this is because we only follow subjects from the second dose forwards, so there has already been a large degree of self-selection with regard to the role of socioeconomic factors in our study participants.

Implications

Reducing the number of HPV vaccine doses from three to two could potentially lead to a number of positive effects, including lower costs, increased compliance and improved logistics of the vaccination programme. It is however key to remain vigilant with regards to follow-up of disease outcomes and supplement clinical trial data and policy recommendations with real life evidence, such as those presented here. The findings imply that the current recommendation of two-dose schedules is appropriate, but we reinforce the significance of optimal timing between doses.

Unanswered questions and future research

We did not consider HPV-related disease outcomes other than condyloma. More studies with longer follow-up time are needed to ascertain the effectiveness of a two-dose schedule for HPV-related disease outcomes such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or cervical cancer. As more countries implement two-dose schedules, the impact on transmission dynamics and herd immunity will also become clearer.22 It should also be taken into account that the duration of protection for both the two-dose and three-dose schedules is not yet known and more time and data are required before conclusions can be drawn regarding the long-term effectiveness of these schedules, and a reduced-dose schedule can be recommended for girls older than 15 years.2 31

The finding that the 8+ months between doses was less protective that the 4–7 months group was unexpected as for one-dose priming schedules it is often better with a longer interval between doses. Since this is an observational study, we cannot exclude that our finding was due to an unmeasured confounding factor, however, with some (unknown) underlying reason why these girls had a longer time to dose three and high incidence/exposure. While we can only speculate about this higher risk in the 8+ months group, it has highlighted the need for further studies with a longer follow-up time investigating the upper time limit between doses and vaccine effectiveness.

Conclusion

For prevention of condyloma, a two-dose schedule of qHPV vaccine with 4–7 months between first and second doses may be as effective as standard three-dose vaccination, for women first vaccinated before the age of 20 years. The results from this nationwide observational study support immunogenicity findings from clinical trials.

bmjopen-2016-015021supp003.docx (42.6KB, docx)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FL, EH, AP, KS, IU, PS and LAD contributed to the design of the study; FL, EH, AP and PS analysed the data; FL drafted the manuscript; FL, EH, AP, KS, IU, PS and LAD critically reviewed the manuscript; FL, EH, AP, KS, IU, PS and LAD prepared the manuscript for submission; LAD is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: This study was supported by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic research grant number KF10-0046. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of manuscript or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; LAD has received research grants to her institution for other studies from MSD Sanofi Pasteur, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and GlaxoSmithKline. KS has received grants from Merck Sharp and Dohme for other studies on HPV vaccination in Sweden; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The study uses unique individual level Swedish register data, which cannot be shared in the public domain according to Swedish law. The individual-level data underlying the study will be available from the corresponding author upon request, given that appropriate ethical and legal requirements are met.

References

- 1.Schiller JT, Lowy DR. Raising expectations for subunit vaccine. J Infect Dis 2015;211 10.1093/infdis/jiu648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson SR, McNeil S, Dionne M, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:1793–802. 10.1001/jama.2013.1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazcano-Ponce E, Stanley M, Muñoz N, et al. Overcoming barriers to HPV vaccination: non-inferiority of antibody response to human papillomavirus 16/18 vaccine in adolescents vaccinated with a two-dose vs. a three-dose schedule at 21 months. Vaccine 2014;32:725–32. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuzil KM, Canh DG, Thiem VD, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of alternative schedules of HPV vaccine in Vietnam: a cluster randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA 2011;305:1424–31. 10.1001/jama.2011.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson LM, et al. Immune response to the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a 2-dose or 3-dose schedule up to 4 years after vaccination: results from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014;10:1155–65. 10.4161/hv.28022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson LM, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a 2-dose schedule compared with the licensed 3-dose schedule: results from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin 2011;7:1374–86. 10.4161/hv.7.12.18322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Human papillomavirus vaccines: who position paper,. 2014. http://www.who.int/wer/2014/wer8943.pdf?ua=1.

- 8.European Medicines Agency. Assessment report Gardasil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blomberg M, Dehlendorff C, Sand C, et al. Dose-Related differences in effectiveness of Human Papillomavirus vaccination against Genital warts: a Nationwide study of 550,000 Young girls. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:676–82. 10.1093/cid/civ364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67. 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organisation. International classification of disease. Tenth Revision 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leval A, Herweijer E, Ploner A, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness: a swedish national cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:469–74. 10.1093/jnci/djt032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herweijer E, Leval A, Ploner A, et al. Association of varying number of doses of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine with incidence of condyloma. JAMA 2014;311:597–603. 10.1001/jama.2014.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen KE, Munk C, Sparen P, et al. Women's sexual behavior. Population-based study among 65,000 women from four Nordic countries before introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:459–67. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donken R, Knol MJ, Bogaards JA, et al. Inconclusive evidence for non-inferior immunogenicity of two- compared with three-dose HPV immunization schedules in preadolescent girls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2015;71:61–73. 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernández-Ávila M, Torres-Ibarra L, Stanley M, et al. Evaluation of the immunogenicity of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine using 2 versus 3 doses at month 21: an epidemiological surveillance mechanism for alternate vaccination schemes. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:30–8. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1058458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krajden M, Cook D, Yu A, et al. Assessment of HPV 16 and HPV 18 antibody responses by pseudovirus neutralization, Merck cLIA and Merck total IgG LIA immunoassays in a reduced dosage quadrivalent HPV vaccine trial. Vaccine 2014;32:624–30. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson L, et al. Sustained immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a two-dose schedule in adolescent girls: five-year clinical data and modeling predictions from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:20–9. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1065363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safaeian M, Porras C, Pan Y, et al. Durable antibody responses following one dose of the bivalent human papillomavirus L1 virus-like particle vaccine in the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial. Cancer Prev Res 2013;6:1242–50. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariani L, Vici P, Suligoi B, et al. Early direct and indirect impact of quadrivalent HPV (4HPV) vaccine on genital warts: a systematic review. Adv Ther 2015;32:10–30. 10.1007/s12325-015-0178-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogaards JA, Berkhof J. Assessment of herd immunity from human papillomavirus vaccination. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:896–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70324-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donken R, Bogaards JA, van der Klis FR, et al. An exploration of individual- and population-level impact of the 2-dose HPV vaccination schedule in pre-adolescent girls. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:1381–93. 10.1080/21645515.2016.1160978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donovan B, Franklin N, Guy R, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination and trends in genital warts in Australia: analysis of national sentinel surveillance data. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:39–44. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70225-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MA, Liu B, McIntyre P, et al. Fall in genital warts diagnoses in the general and indigenous australian population following implementation of a national human papillomavirus vaccination program: analysis of routinely collected national hospital data. J Infect Dis 2015;211:91–9. 10.1093/infdis/jiu370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowe E, Pandeya N, Brotherton JM, et al. Effectiveness of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine for the prevention of cervical abnormalities: case-control study nested within a population based screening programme in Australia. BMJ 2014;348:g1458 10.1136/bmj.g1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gertig DM, Brotherton JM, Budd AC, et al. Impact of a population-based HPV vaccination program on cervical abnormalities: a data linkage study. BMC Med 2013;11:227 10.1186/1741-7015-11-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herweijer E, Sundström K, Ploner A, et al. Quadrivalent HPV vaccine effectiveness against high-grade cervical lesions by age at vaccination: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 2016;138:2867–74. 10.1002/ijc.30035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svahn MF, Munk C, von Buchwald C, et al. Burden and incidence of human papillomavirus-associated cancers and precancerous lesions in Denmark. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:551–9. 10.1177/1403494816653669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garland SM, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N, et al. Impact and effectiveness of the Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: a Systematic Review of 10 years of Real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:519–27. 10.1093/cid/ciw354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herweijer E, et al. Population-Based Cohort Study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jit M, Brisson M, Laprise JF, et al. Comparison of two dose and three dose human papillomavirus vaccine schedules: cost effectiveness analysis based on transmission model. BMJ 2015;350:g7584 10.1136/bmj.g7584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015021supp001.docx (15.9KB, docx)

bmjopen-2016-015021supp002.pdf (70.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015021supp003.docx (42.6KB, docx)