Abstract

AnchorQuery (http://anchorquery.csb.pitt.edu) is a web application for rational structure‐based design of protein–protein interaction (PPI) inhibitors. A specialized variant of pharmacophore search is used to rapidly screen libraries consisting of more than 31 million synthesizable compounds biased by design to preferentially target PPIs. Every library compound is accessible through one‐step multi‐component reaction (MCR) chemistry and contains an anchor motif that is bioisosteric to an amino acid residue. The inclusion of this anchor not only biases the compounds to interact with proteins, it also enables a rapid, sublinear time pharmacophore search algorithm. AnchorQuery provides all the tools necessary for users to perform online interactive virtual screens of millions of compounds, including pharmacophore elucidation and search, and enrichment analysis.

Accessibility: AnchorQuery is freely accessible at http://anchorquery.csb.pitt.edu.

Keywords: virtual screening, multicomponent reactions, compound libraries, pharmacophore, small‐molecules

Introduction

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are difficult targets for drug discovery since the PPI interface is typically large and flat and not amenable to small‐molecule binding.1 However, in many protein–protein interactions there are anchor side chains: side chains that bury a large amount of surface area at the core of the binding interface2, 3 and are usually energetic hot spots.4 AnchorQuery provides a means for targeting protein–protein interactions with small‐molecules by combining the anchor concept with “one‐step, one pot” multicomponent reaction (MCR) chemistry5, 6, 7 and an interactive web‐based interface. Here we provide a brief overview of the AnchorQuery approach and outline the typical usage of the web application from query construction to minimization and scoring. Additional documentation, including a user guide, video tutorials, and interactive examples, is available on the website, http://anchorquery.csb.pitt.edu.

Approach

Since its initial description,8 AnchorQuery has been improved both in terms of content (millions of new compounds) and functionality (advanced analytics). The core of the AnchorQuery approach is the anchor‐biased libraries of MCR‐accessible compounds. AnchorQuery now supports anchor mimics of seven amino acid residues: tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine, valine/leucine, and aspartic/glutamic acid. Each anchor‐oriented library contains compounds generated from 27 different MCR reactions by sampling from hand‐selected collections of starting materials for a total of about six million compounds, represented by hundreds of millions of explicitly generated conformations, per a library. Detailed information about the content of the libraries is published on the website and individual compounds are dynamically linked to their custom reaction schema.

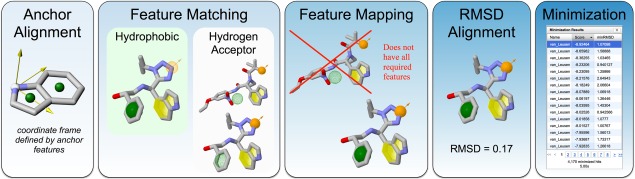

The computational workflow for performing an AnchorQuery search is shown in Figure 1. Compounds are stored with respect to the coordinate system defined by the mandatory anchor. Molecular conformations containing a pharmacophore feature at a specific location in this anchor‐oriented coordinate system can be efficiently identified through queries to a spatial data structure.9 Unlike coordinate‐frame independent spatial query methods, such as Pharmer,10 this approach efficiently supports the inclusion of optional features in queries. Once compound conformations matching the query features are identified, molecular features are mapped to the query features and molecules that do not contain all required features are filtered out. The remaining conformations are then rigidly aligned to the minimum root mean square deviation (RMSD) pose to the query. Finally, the RMSD aligned poses can be further refined by saving hits and locally minimized.

Figure 1.

The AnchorQuery computational workflow.

Using AnchorQuery

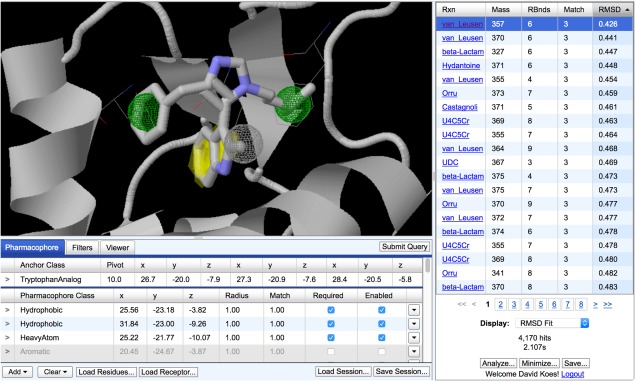

The AnchorQuery search interface is shown in Figure 2. AnchorQuery requires as input a receptor, the target for small molecule modulation, and a ligand including an W, Y, F, V, L, E, or D anchor side chain.2, 3 The ligand is often constructed from the key residues interacting with a receptor in a PPI. The PPI can be a cocrystal or a docked model. Specifically, AnchorQuery requires the 3D structures of both the receptor (or at a minimum the binding site) and the ligand (or at a minimum just the anchor). These structures may be uploaded manually using the “Load Residues” and “Load Receptor” links, or can be identified using PocketQuery12 and automatically exported to a new AnchorQuery session. AnchorQuery automatically lists all the potential anchors found in the ligand structure that could be targeted with our anchor‐biased libraries. It also lists all the pharmacophore features (steric, hydrophobic, charged, or hydrogen bonding groups) detected in the ligand structure. Users can also design their own pharmacophores, including “heavy atom,” anywhere in the searching volume. However, anchors must be uploaded as part of the ligand structure. The user must then select the anchor and pharmacophore features as desired to be searched in our libraries. For example, in Figure 2, two hydrophobic features and one heavy atom (steric) feature extracted from key p53 residues of the p53/MDM2 interface are enabled and required in the query. The spatial tolerance for matching a feature is specified in terms of a spherical radius for the regular features and a pivot for the anchor, which limits how much the anchor may rotate from the specified position. A “match” value may also be applied to each feature to assist in sorting and filtering results from queries with multiple optional features. For example, a query can be constructed to only return compounds that match at least two out of any four optional features and the results can be sorted so the compounds that match the most features are ranked first. Additional “drug‐like” filters can be applied to select compounds from specific reactions or that fall within a specified range of molecular weight or number of rotatable bonds. If a receptor structure is provided, compounds that sterically clash with the receptor structure in their anchor‐oriented or RMSD‐oriented pose can be filtered out.

Figure 2.

The AnchorQuery web‐based interface for pharmacophore search. An example query derived from the p53/MDM2 PPI is shown (PDB ID 1YCR). Three key residues of p53 (thin wireframe) are shown with the MDM2 receptor (cartoon), the pharmacophore query (spheres and yellow anchor indicator), and a matching compounds based on the van Leusen imidazole MCR from the tryptophan‐biased library (sticks). Molecular visualization is provided by JSmol.11

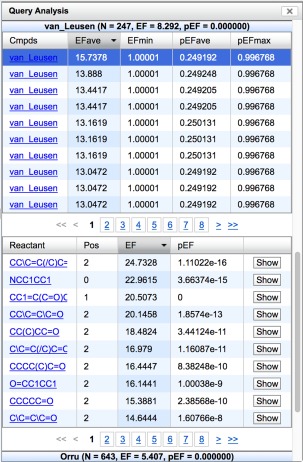

Once a query is defined, since searching (“Submit Query”) typically takes on the order of seconds, it can be iteratively refined. The results of the search can be individually visualized and evaluated, as shown in Figure 2, or the query analytics module (“Analyze”) can be used to assess aggregate properties of the results, such as the distribution of molecular weights, rotatable bond count, feature match count, or RMSDs. More interestingly the enrichment factor (EF) of reactions and starting materials is computed along with a P value (pEF, where the null hypothesis is that results are a random sample of the library). As an example, in Figure 3, the compounds generated using the van Leusen reaction were enriched in the results by a factor of 8.3, which is highly significant. This allows chemists to prioritize scaffolds for first synthesis.13 All result compounds from this reaction are shown (and can be interactively viewed) along with aggregate (min, average, and max) statistics for the enrichment of their starting materials. Additionally, the enrichments for individual starting materials are shown, and these can be expanded to show all the compounds containing a given starting material. This analysis facility is expected to be particularly useful to synthetic chemists seeking to expand beyond the sampling of chemical space provided by AnchorQuery (e.g., by making molecules from the most enriched starting materials).

Figure 3.

The snippet of the Query Analysis module output showing enrichment factors (EF) with statistical significance (pEF) for reactions and starting materials in the results of a search.

Discussion

A key differentiating feature of the AnchorQuery approach to other virtual screening approaches is the large MCR chemical space. MCR technology allows to instantaneously (one‐pot) synthesize complex target molecules to test binding hypotheses in a fast manner. In classical multistep procedures synthesis of target compounds is time consuming. Based on multiple projects performed in the authors' laboratories, the time advantage is three‐ to tenfold. All MCRs used to build the virtual libraries and their corresponding starting materials are hand selected with previous synthetic experience and tested for synthetic feasibility. As a consequence, the synthesis success rate is very high (>90%). Moreover, the MCR space used in AnchorQuery is completely novel and does not contain any previously described compounds.

The AnchorQuery web application is freely available for noncommercial education and research purposes. Since its inception, AnchorQuery has processed more than 31,000 queries. As measured by Google Analytics, in the 12 months from June 2016 to June 2017, more than 1100 users engaged in more than 1800 interactive sessions with more than 400 sessions lasting longer than 3 min. Importantly, AnchorQuery was used as part of the development of novel p53/MDM2 inhibitors14, 15 and an allosteric PDK1 modulator.13 We believe that AnchorQuery is a powerful tool for targeting protein–protein interactions using structure‐based design and novel chemistry.

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Nooren IMA, Thornton JM (2003) Diversity of protein‐protein interactions. EMBO J 22:3486–3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rajamani D, Thiel S, Vajda S, Camacho CJ (2004) Anchor residues in protein–protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11287–11292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kimura SR, Brower RC, Vajda S, Camacho CJ (2001) Dynamical view of the positions of key side chains in protein‐protein recognition. Biophys J 80:635–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clackson T, Wells JA (1995) A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone‐receptor interface. Science 267:383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weber L (2002) Multi‐component reactions and evolutionary chemistry. Drug Discov Today 7:143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hulme C, Gore V (2003) Multi‐component reactions: emerging chemistry in drug discovery from Xylocain to Crixivan. Curr Med Chem 10:51–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Domling A, Wang W, Wang K (2012) Chemistry and biology of multicomponent reactions. Chem Rev 112:3083–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koes D, Khoury K, Huang Y, Wang W, Bista M, Popowicz GM, Wolf S, Holak TA, Domling A, Camacho CJ (2012) Enabling large‐scale design, synthesis and validation of small molecule protein‐protein antagonists. PLoS One 7:e32839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Samet H. 2006. Foundations of multidimensional and metric data structures. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koes DR, Camacho CJ (2011) Pharmer: efficient and exact pharmacophore search. J Chem Inform Model 51:1307–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanson RM, Prilusky J, Renjian Z, Nakane T, Sussman JL (2013) JSmol and the next‐generation web‐based representation of 3D molecular structure as applied to Proteopedia. Israel J Chem 53:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koes DR, Camacho CJ (2012) PocketQuery: protein–protein interaction inhibitor starting points from protein–protein interaction structure. Nucleic Acids Res 40:W387–W392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kroon E, Schulze JO, Süß E, Camacho CJ, Biondi RM, Dömling A (2015) Discovery of a potent allosteric kinase modulator by combining computational and synthetic methods. Angew Chem 127:14139–14142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Surmiak E, Neochoritis CG, Musielak B, Twarda‐Clapa A, Kurpiewska K, Dubin G, Camacho C, Holak TA, Dömling A (2017) Rational design and synthesis of 1, 5‐disubstituted tetrazoles as potent inhibitors of the MDM2‐p53 interaction. Eur J Med Chem 126:384–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shaabani S, Neochoritis C, Twarda‐Clapa A, Musielak B, Holak T, Dömling A (2017) Scaffold hopping via ANCHOR. QUERY: β‐lactams as potent p53‐MDM2 antagonists. MedChemComm 8:1046–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]