The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced duty hour reforms for resident physicians in 2003, which included the current 80-hour maximum work week, averaged over 4 weeks; subsequent 2011 work hour reforms included policies limiting maximum shift lengths for intern physicians.1 Both reforms stemmed from a growing concern about the effects of resident fatigue on both patient safety and resident well-being.1,2 There has been much debate surrounding these reforms, and opponents have argued that they have negatively affected resident education.2,3 After assessing these concerns and the findings from a recent study of flexible models of resident education, the ACGME approved new 2017 work hour standards.2,4

However, there remains a lack of data on the actual impact of work hour reforms. Previous studies have evaluated surgical resident certification examination scores as a proxy for quality of resident education in the context of duty hour reforms.3 We analyzed first-time taker pass rates for the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) initial certification examination, a standardized examination independent from the ACGME, to evaluate whether 2003 or 2011 ACGME duty hour reforms were associated with differences in internal medicine (IM) resident pass rates on a national certification examination.5

Our analysis reflected a 20-year span from 1996 to 2016 and included 151 844 test takers. Since reforms were implemented in 2003 and 2011, aggregate scores for the 3 surrounding periods (1996–2003, 2004–2011, and 2012–2016) were compared with an analysis of variance (ANOVA). All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Use, reproduction, and analysis of these data were approved by the ABIM. This work was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts General Hospital and deemed exempt.

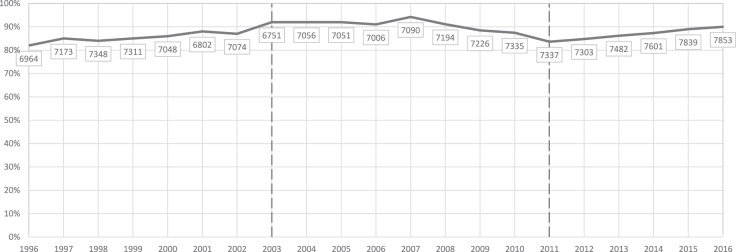

The number of first-time takers ranged from 6751 (2003) to 7853 (2016); pass rates ranged from 82% (1996) to 94% (2007; Figure). Mean pass rates ± SD were 86% ± 2.9 (1996–2003), 90% ± 3.3 (2004–2011), and 87% ± 2.1 (2012–2016). There were no significant differences in pass rates for the 3 periods (ANOVA, P > .05).

Figure.

Internal Medicine Certifying Examination Pass Rates for First-Time Test Takers (1996–2016)

Note: The number of test takers is indicated below each time point. Broken lines reflect implementation of the 2003 and 2011 ACGME reforms.

Our analysis did not reveal any significant difference in examination pass rates for IM residents surrounding either change in the ACGME work hour standards. That finding does not support previously held concerns that work hour reforms have negatively impacted resident education, at least as measured by a standardized test of medical knowledge—a concern that, in part, led to the 2017 revisions in the ACGME duty hour standards.2–4

Our work has limitations. This was an observational analysis that did not account for possible unobserved confounders. Fortunately, the initial certification examination is regularly reviewed by the ABIM to equate scores among administrations; thus, the nonsignificant year-to-year variation seen in examination scores likely represents natural variation due to varying ability of the examination taker populations.

Given the ongoing debate around duty hour reforms, the recent ACGME policy revisions, and the ongoing efforts by researchers conducting the iCOMPARE trial (an IM study piloting alternative models of resident education), further study is warranted to determine whether any other educational outcomes have been measurably affected by duty hour reforms.5

References

- 1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The ACGME 2011 duty hour standards: enhancing quality of care, supervision, and resident professional development. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/jgme-monograph[1].pdf. Accessed October 13, 2017.

- 2. Bilimoria KY, Chung JW, Hedges LV, et al. National cluster-randomized trial of duty-hour flexibility in surgical training. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374 8: 713– 727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rajaram R, Chung JW, Jones AT, et al. Association of the 2011 ACGME resident duty hour reforms with general surgery patient outcomes and with resident examination performance. JAMA. 2014; 312 22: 2374– 2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements, clinically driven standards. https://www.acgmecommon.org/2017_requirements. Accessed October 13, 2017.

- 5. iCOMPARE. Comparative effectiveness of models optimizing patient safety and resident education. http://www.jhcct.org/icompare/default.asp. Accessed October 13, 2017.