Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite being one of the leading risk factors of cardiovascular mortality, there are limited data on changes in hypertension burden and management from India. This study evaluates trend in the prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the urban and rural areas of India’s National Capital Region (NCR).

Design and setting

Two representative cross-sectional surveys were conducted in urban and rural areas (survey 1 (1991–1994); survey 2 (2010–2012)) of NCR using similar methodologies.

Participants

A total of 3048 (mean age: 46.8±9.0 years; 52.3% women) and 2052 (mean age: 46.5±8.4 years; 54.2% women) subjects of urban areas and 2487 (mean age: 46.6±8.8 years; 57.0% women) and 1917 (mean age: 46.5±8.5 years; 51.3% women) subjects of rural areas were included in survey 1 and survey 2, respectively.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Hypertension was defined as per Joint National Committee VII guidelines. Structured questionnaire was used to measure the awareness and treatment status of hypertension. A mean systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg was defined as control of hypertension among the participants with hypertension.

Results

The age and sex standardised prevalence of hypertension increased from 23.0% to 42.2% (p<0.001) and 11.2% to 28.9% (p<0.001) in urban and rural NCR, respectively. In both surveys, those with high education, alcohol use, obesity and high fasting blood glucose were at a higher risk for hypertension. However, the change in hypertension prevalence between the surveys was independent of these risk factors (adjusted OR (95% CI): urban (2.3 (2.0 to 2.7)) rural (3.1 (2.4 to 4.0))). Overall, there was no improvement in awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension in the population.

Conclusion

There was marked increase in prevalence of hypertension over two decades with no improvement in management.

Keywords: Hypertension, Pre-Hypertension, Secular trends, Cardiovascular disease risk factors, India

Strengths and limitations of the study.

One of the first studies to report the trends in the population burden and management of hypertension from the low-income and middle-income countries.

The study surveyed representative samples from the same population using similar methodologies and was adequately powered to compare hypertension burden at two time periods.

The instrument used for blood pressure measurement was different in the two studies. This was inevitable since the apparatus used in first survey was unavailable at the time of the next survey.

Behavioural risk factors like diet and physical activity were not assessed during the first survey and therefore not reported and they could account for difference in blood pressure levels as discussed.

The study being restricted to urban and rural National Capital Region of Delhi, may not be generalisable across India.

Introduction

High blood pressure (HBP) is the single largest risk factor for disease burden worldwide. In India, HBP has now emerged as a leading risk factor for mortality.1 Several studies over the years have shown increasing prevalence of hypertension in India.2–4 Kearney et al in their paper predicted that the burden of hypertension in India is expected to almost double from 118 million in 2000 to 213.5 million by 2025.5 A recent systematic analysis suggested high prevalence with poor awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in India.6

At the population level, the effect of rise in blood pressure is continuous with increasing cardiovascular risk with rise of blood pressure above 115/75 mm Hg.7 According to the Global Burden of Disease-2015 analysis, the estimated rate of annual deaths associated with systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 110–115 mm Hg between 1990 and 2015 has increased from 135.6 to 145.2 per 100 000 persons.8 However, data from India on trends of population blood pressure distribution, hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in representative population over time are scarce due to absence of active surveillance. These data are important to formulate informed policy as HBP is one of the key targets to reduce premature mortality due to cardiovascular diseases (CVD) set by WHO and the Indian government.9 10

We conducted two surveys on prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors between April 1991 and June 1994 (survey 1) and August 2010 and January 2012 (survey 2) in National Capital Region (NCR) of India (urban Delhi and adjoining rural Haryana). These surveys enabled us to estimate the changes in blood pressure prevalence and management in this population over this time period.

Methods

Study population and sample size

The two cross-sectional surveys were carried out in adults aged 35–64 years using a multistage cluster random sampling method in the urban area and a simple random sampling method in the rural area to assess the prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) and its risk factors. The sample size was calculated based on estimated prevalence of CAD in the population. The details of sample size calculation were published elsewhere.11 Based on this, 5535 participants were recruited for survey 1 (urban: 3048; rural: 2487) and 3969 were recruited for survey 2 (urban: 2052; rural: 1917). In both surveys, all eligible individuals from the primary sampling unit (household) were approached for their consent to participate in the survey.

Data collection

Both the surveys got ethical clearance from institutional ethics committees of the participating institutions. The data were collected through household visits using a standardised questionnaire. Blood sampling was done through physician-led medical camps using standardised equipments and methods. In survey 1, blood pressure was measured using a random zero sphygmomanometer, whereas in survey 2, an automated blood pressure machine (OMRON (HEM-7080)) was used. In both surveys, two blood pressure readings were recorded in sitting position, 5 min apart. If the difference between the two readings was more than 10 mm Hg, a third measurement was taken. The mean of the last two measurements were taken for final analysis. Operational definitions were as follows: prehypertension and hypertension were defined using the Joint National Committee VII criteria12 (SBP 120–139 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 80–89 mm Hg for prehypertension and SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg or on blood pressure lowering medication for hypertension). Those who were diagnosed with hypertension were further classified in to stage I (SBP 140–159 mm Hg and/or DBP 90–99 mm Hg) and stage II (SBP ≥160 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥100 mm Hg).

Hypertension awareness, treatment and control were analysed in hypertensive participants based on questionnaires and blood pressure measurements. Among the hypertensive participants, self-report of any previous clinical diagnosis of hypertension was defined as awareness of hypertension. Self-reported antihypertension medication use was defined as on treatment and a mean SBP <140 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg was defined as control of hypertension among the participants with hypertension.

Statistical analysis

STATA 12.1 was used for the statistical analysis. Prevalence of hypertension along with their SEs and ratios between survey 1 and survey 2 and the awareness, treatment and control levels during survey 1 and survey 2 are presented. The age-adjusted and gender-adjusted prevalence of hypertension were calculated using Indian census data for 2011 as standard population. Hypertension prevalence was analysed by selected demographic and health characteristics: gender, place of residence (urban/rural), age category (35–44, 45–54, 55–64 years), educational status, body mass index (BMI), blood glucose level and alcohol use. Educational status was defined as follows: low (illiterate to primary level), medium (middle to high school) and high (higher secondary and above). WHO cut-offs were used to categorise BMI values (normal: BMI <25 kg/m2, overweight: BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2, obesity: BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and abdominal obesity (waist to hip ratio >0.90 for men and >0.85 for women). Blood glucose levels were categorised as normoglycaemic (fasting plasma glucose (FPG) <100 mg/dL), impaired fasting glucose (FPG 100 to <126 mg/dL) and diabetes (FPG≥126 mg/dL). Alcohol use was defined as any use in the last 12 months of any alcohol product. The difference in proportions between the surveys was evaluated using χ2 test. Any p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Logistic regression models were constructed for urban and rural populations separately defining prevalence of hypertension as outcome variable and time period (survey 2 vs survey 1) as exposure variables. We added covariates as categorical variables (age groups, gender, obesity, waist to hip ratio, diabetes and alcohol use), stepwise to the logistic regression model. Adjusted ORs and 95% CIs were reported. We also assessed the interaction between time (survey 1; survey 2) and other covariates mentioned above using likelihood test. If the interaction was found to be significant, then stratified analysis was reported. We additionally conducted a sensitivity analysis to account for suboptimal response for biochemical data in survey 1 (<65%) by applying inverse probability weighting (IPW).13 Those who did not participate for blood collection were more likely to be females, lesser educated, smokers and with low BMI. The IPW approach weighted the analysis by the inverse of the predicted probability of being observed at a given time point. This was computed based on a logistic model with gender, education, smoking status and BMI as predictors for non-response bias for survey 1 and gender, education, smoking status, BMI, time of survey and site as predictors for both survey together.

Results

A total of 3048 (mean (SD) age: 46.8 (9.0) years; 52.3% females) and 2052 (mean (SD) age: 46.5 (8.4) years; 54.2% females) subjects of urban areas and 2487 (mean (SD) age: 46.6 (8.8) years; 57.0% females) and 1917 (mean (SD) age: 46.5 (8.5) years; 51.3% females) subjects of rural areas were recruited in survey 1 and survey 2, respectively. Ninety-nine per cent of the participants in both surveys had their blood pressure measured. Among those surveyed, 95% and 78% in survey 1 and survey 2, respectively, of the urban sample and 51% and 65% in survey 1 and survey 2, respectively, of the rural sample agreed to provide a fasting blood sample for biochemical analysis.

The prevalence of hypertension increased from 23.0% to 42.2% and 11.2% to 28.9% in urban and rural NCR of Delhi, respectively between the two surveys. The increase in prevalence was by 83% in urban NCR and 158% in rural NCR. The rise in prevalence was more in men with a rise of 94% and 73% in urban areas and 191% and 125% in rural areas in men and women, respectively (table 1). The age-specific prevalence of hypertension revealed an increase in prevalence at all ages except in the highest age group (55–64 years) of urban men and women. The rise in age-specific prevalence was highest in the youngest age group (35–44) with a rise in prevalence of 153%, 115%, 239% and 336%, in urban men, urban women, rural men and rural women, respectively.

Table 1.

Age and sex standardised and age-specific prevalence of hypertension: survey 1 and survey 2

| Rural | Urban | |||||||||||||||

| Survey 1 | Survey 2 | Survey 1 | Survey 2 | |||||||||||||

| n | Prevalence (%) | SE | n | Prevalence (%) | SE | p Value difference | Ratio (95% CI) | n | Prevalence (%) | SE | n | Prevalence (%) | SE | p Value difference | Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Total | 2469 | 11.2 | 0.01 | 1914 | 28.9 | 1 | <0.001 | 2.6 (2.3 to 2.9) | 3041 | 23 | 0.01 | 2026 | 42.2 | 1.1 | <0.001 | 1.8 (1.6 to 1.9) |

| Men | 1065 | 12.2 | 0.01 | 981 | 32.6 | 1.5 | <0.001 | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.3) | 1451 | 22.3 | 0.01 | 924 | 43.3 | 1.6 | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.3) |

| Women | 1404 | 10.2 | 0.01 | 933 | 25.2 | 1.4 | <0.001 | 2.5 (2.4 to 3.6) | 1590 | 23.8 | 0.01 | 1102 | 41.1 | 1.4 | <0.001 | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) |

| Men | ||||||||||||||||

| 35–44 | 441 | 8.1 | 0.01 | 459 | 27.4 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 3.4 (2.4 to 4.8) | 646 | 13.4 | 0.01 | 434 | 33.9 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.3) |

| 45–54 | 318 | 12.2 | 0.02 | 315 | 36.1 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 3.0 (2.1 to 4.1) | 432 | 21.6 | 0.02 | 299 | 47.9 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.8) |

| 55–64 | 306 | 21.6 | 0.02 | 207 | 38.6 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.4) | 373 | 34.5 | 0.03 | 191 | 42.5 | 0.02 | NS | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.6) |

| Women | ||||||||||||||||

| 35–44 | 667 | 4.3 | 0.01 | 433 | 18.7 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 4.4 (3.1 to 6.9) | 723 | 12.8 | 0.01 | 521 | 27.6 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.8) |

| 45–54 | 438 | 9.4 | 0.01 | 277 | 28.5 | 0.03 | 0.001 | 3.0 (2.2 to 4.4) | 450 | 25.9 | 0.02 | 321 | 46.9 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.2) |

| 55–64 | 299 | 23.1 | 0.02 | 223 | 33.3 | 0.03 | 0.011 | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) | 417 | 57.6 | 0.04 | 260 | 59.8 | 0.03 | NS | 1.0 (0.99 to 1.6) |

Ratio, survey 2/survey 1.

n, sample size; NS, not statistically significant.

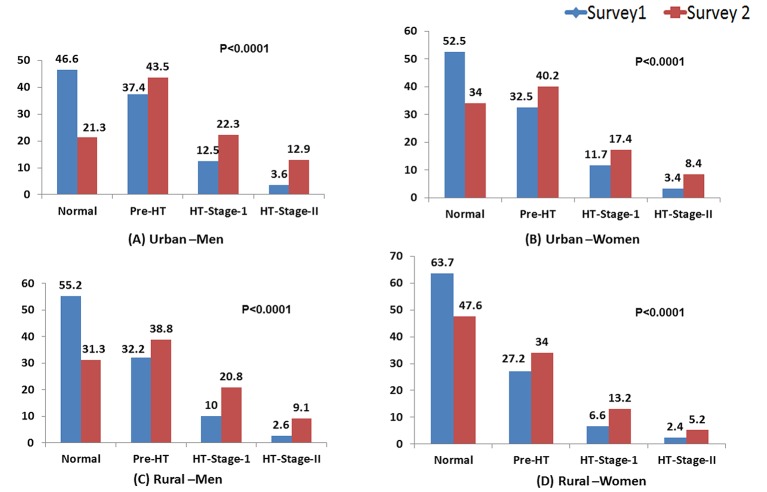

The distribution of blood pressure in the population (excluding those on antihypertensive therapy) changed significantly over the years. In survey 2, there was lesser proportion of the people with optimum blood pressure values (BP<120/80 mm Hg) and a higher proportion of individuals with prehypertension, stage I and stage II hypertension (figure 1)compared with survey 1. This change of distribution was similar across men and women in NCR and also both in urban and rural areas.

Figure 1.

Distribution of blood pressure categories (%) in untreated population of National Capital Region of Delhi: (A) urban men, (B) urban women, (C) rural men and (D) rural women. HT, hypertension.

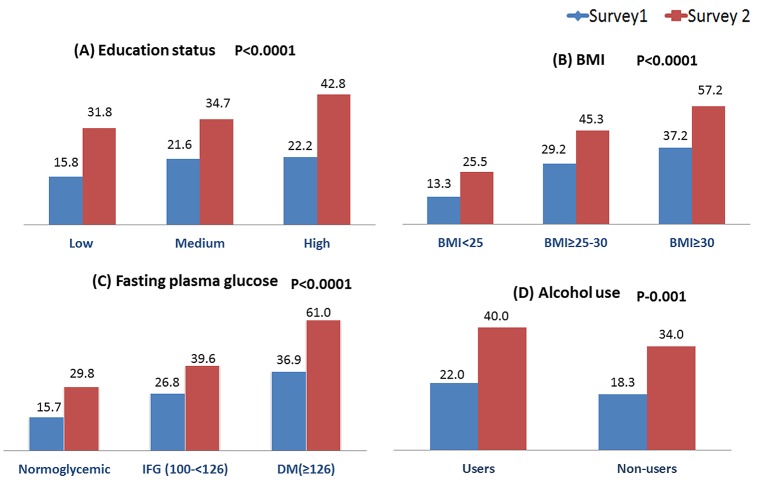

The prevalence of hypertension was stratified by other known risk factors associated with blood pressure (figure 2). Hypertension prevalence increased with increasing BMI and education categories in both urban and rural population (figure 2). The prevalence was highest among those with diabetes followed by those with impaired fasting blood glucose in both urban and rural areas (figure 2). Alcohol users had higher prevalence of hypertension (figure 2). The prevalence increased in each of these categories in survey 2 as compared with survey 1.

Figure 2.

Prevalence (%) of hypertension stratified by risk factors: (A) education status, (B) body mass index (BMI), (C) fasting plasma glucose and (D) alcohol use.

The distribution of risk factors in those with and without hypertension in urban and rural areas is as given in online supplementary table 1. The prevalence of alcohol use, obesity, abdominal obesity and diabetes increased significantly among those with hypertension in survey 2 compared with survey 1. The relative increase in hypertension prevalence between the surveys was modelled as if there was no change in these risk factors and the demographic profile between the surveys. The increased OR of hypertension in survey 2 as compared with survey 1 persisted even after adjusting for these factors. On analysis, a significant interaction between time and age was observed. The age stratified models suggested higher odds of change in hypertension prevalence among the youngest age group in both urban and rural areas (table 2). The sensitivity analysis using IPW did not show any significant difference in the estimates after accounting for the suboptimal response for blood sampling in survey 1 (data not shown).

Table 2.

Odds of hypertension in survey 2 relative to odds for hypertension in survey 1

| OR (95% CI) | ||

| Rural | Urban | |

| Unadjusted | 3.2 (2.7 to 3.8) | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.6) |

| Model 1: Adjusted for age | 3.4 (2.9 to 4.0) | 2.6 (2.3 to 2.9) |

| Model 2: Adjusted for age and gender | 3.3 (2.8 to 3.9) | 2.6 (2.3 to 2.9) |

| Model 3: Adjusted for age, gender and obesity | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.6) | 2.6 (2.2 to 2.9) |

| Model 4: Adjusted for age, gender and WHR | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.6) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.8) |

| Model 5: Adjusted for age, gender, obesity and WHR | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.4) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.8) |

| Model 6: Adjusted for age, gender, obesity, WHR and diabetes | 3.3 (2.6 to 4.1) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.7) |

| Model 7: Adjusted for age, gender, obesity, WHR, diabetes and alcohol use | 3.1 (2.4 to 4.0) | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.7) |

| Model 8: Model 7 stratified by age groups | ||

| Age 35–44 years | 5.0 (3.0 to 8.4) | 2.7 (2.1 to 3.4) |

| Age 45–54 years | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.6) |

| Age 55–64 years | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.9) | 2.6 (1.9 to 3.4) |

Obesity: BMI ≥30 kg/m2; diabetes: FPG ≥126 mg/dL or on medication; abdominal obesity: WHR >0.90 for men and WHR >0.85 for women; p value for interaction between time and age (rural), p=0.0001; p-value for interaction between time and age (urban), p=0.0008.

BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; WHR, waist to hip ratio.

bmjopen-2016-015639supp001.pdf (272.6KB, pdf)

There was no change in the overall awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension between the two surveys in the NCR (table 3). When stratified by gender, the awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension in men decreased in the second survey while awareness and treatment but not control rates improved in women. The overall rates of all three parameters were higher in woman than men. Similarly, in urban areas, there was no change in the overall awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension between the two surveys though all three parameters decreased in men with no significant change in women with higher overall rates in women. In rural NCR, the overall awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension improved between the two surveys. This was seen in men and women except for control rates in men which did not improve. However, though all three rates improved in rural areas, the overall awareness (46.4% vs 26.8%), treatment (40.0% vs 20.4%) and control rates (15.9% vs 8.0%) in rural areas remained much lower than in urban areas.

Table 3.

Hypertension awareness, treatment and control among hypertensive population in National Capital Region of Delhi: survey 1 and survey 2

| Awareness | Treatment | Control | |||||||

| Survey 1 (%) |

Survey 2 (%) |

p Value | Survey 1 (%) |

Survey 2 (%) |

p Value | Survey 1 (%) |

Survey 2 (%) |

p Value | |

| Total | 37.5 | 38.7 | NS | 32.0 | 32.3 | NS | 14.4 | 12.8 | NS |

| Men | 33.1 | 26.8 | 0.02 | 28.3 | 21.1 | 0.01 | 13.1 | 7.1 | 0.01 |

| Women | 41.5 | 51.1 | 0.001 | 35.4 | 43.9 | 0.001 | 15.6 | 18.7 | NS |

| Urban | |||||||||

| Total | 49.0 | 46.4 | NS | 41.6 | 40.0 | NS | 19.0 | 15.9 | NS |

| Men | 44.3 | 34.7 | 0.01 | 37.8 | 29.2 | 0.01 | 17.6 | 10.7 | 0.01 |

| Women | 53.2 | 56.9 | NS | 45.0 | 49.6 | NS | 20.2 | 20.4 | NS |

| Rural | |||||||||

| Total | 7.2 | 26.8 | 0.001 | 6.8 | 20.4 | 0.01 | 2.5 | 8.0 | 0.001 |

| Men | 5.7 | 17.0 | 0.001 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 0.04 | 2.1 | 2.5 | NS |

| Women | 8.7 | 40.0 | <0.001 | 8.7 | 33.2 | <0.001 | 2.9 | 15.3 | <0.001 |

NS, not statistically significant.

Discussion

The repeat survey in NCR of Delhi done after two decades shows (1) continued gradient in urban rural prevalence of hypertension; (2) significant increases in prevalence of hypertension both in urban and rural areas with a higher increase in rural areas; (3) highest increase in prevalence of hypertension in the youngest age group (35–44 years) surveyed; (4) a rightward shift in the distribution of blood pressure in both urban and rural populations with fewer individuals with optimum blood pressure (<120/80); (5) strong relationship between hypertension and BMI, education level, fasting glucose levels and alcohol use; however, even after adjusting for all these predictor variables the odds of hypertension prevalence remained higher in the second survey; (6) no change in overall awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension in NCR.

Prevalence of hypertension has been consistently increasing over the years; however, most reviews from India have included old studies. Recent repeat surveys done in other cities have shown varying results. A study from Jaipur revealed no significant change in hypertension prevalence over two decades from 1990 with a decrease in mean SBP during this period.14 A repeat survey from Chennai showed rise in self-reported prevalence in hypertension in low-income and middle-income groups.15 However, these studies included only urban subjects and used convenience sampling and thus were not representative of the population. Our study done on a representative urban and rural sample revealed that the prevalence of hypertension increased in urban and rural areas with a higher rate of rise in the rural population. A recent systematic review of hypertension found a prevalence of 27.6% in rural India though it was only 16.7% in rural Northern India6 which was at variance with our findings. However, more recent studies from North India have suggested prevalence of 22% and 32% in similar age groups, which is close to the prevalence in our study of 28.9% and those from other parts of rural India.16 17

The age stratified prevalence showed increase in all age groups except the oldest in urban areas, with the highest rate of rise of hypertension in the youngest age group (35–44 years). Indirect evidence of high burden of risk factors in young comes from occurrence of CVD at younger age in South Asians as compared the Caucasians.4 A study among the young individuals (20–30 years) from South India revealed a very high burden of 45.2% of prehypertension in the population.18 However, the rapid rise of the burden of hypertension in young in last two decades has probably been demonstrated for the first time in this study and is worrisome and calls for urgent action to prevent further burden of premature CVD in Indians.

The other important finding was the worsening of population blood pressure levels over two decades with a significantly lower proportion of the population having optimum blood pressure and more of them having prehypertension and hypertension. Small shifts in population blood pressure levels is known to lead to large increases in the burden of CVD in the community7 and thus this also portends future worsening of CVD epidemic in India. It calls for population level intervention like advocacy for salt reduction, weight reduction and increase physical activity. The prevalence of hypertension was expectantly dependant on BMI and fasting glucose levels with higher rates among overweight and obese and those with impaired fasting glucose and diabetes. This finding is consistent across most studies in India and abroad.19–21 The association of hypertension in India with education is variable. A recent large cohort study from South Asia reported higher prevalence among more educated.22 Some have reported reverse gradient with education23 while others have reported no relationship24 25 Alcohol use was associated with higher prevalence of hypertension as seen in other studies.26 Limited data from South Asia suggests higher blood pressure levels in alcohol users27 and also higher probability of myocardial infarction in them than alcohol abstainers28 unlike other population groups. Interestingly, the rise in prevalence of hypertension in survey 2 was significant even after adjusting for these factors. This could be due to other unmeasured lifestyle factors known to be associated with HBP like diet, physical activity, stress and so on, data for which were not available for both studies.

The prevalence, awareness and control rates for hypertension were overall suboptimal with no improvement between the two surveys. The rates of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension were comparable with the pooled estimates reported in systematic reviews with better rates in urban areas as compared with rural areas.2 6 Additionally, these rates were better in women as compared with men, as has been reported consistently in large studies from India and abroad.29 30 This is related to greater health-seeking behaviour in women.30 This study additionally provided insights into the change in these rates over the last two decades which is not available from India earlier. The disturbing fact was that despite rising prevalence of hypertension, there was no improvement in these rates with all three rates worsening in men with improvement in awareness, treatment but not control rates in women. When analysed by site and gender all rates except control rates in men improved in rural areas while in urban areas they worsened in men and remained unchanged in women. However, the overall rates in rural areas were still much lower than urban areas and the improvement in rural areas could be attributed to low rates in the first survey.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study is that it surveyed population representative sample in the same population using similar methodologies and was adequately powered, thus providing opportunity to compare hypertension statistics at two time periods. Such temporal trend was not available from urban and rural areas of India earlier. One of the limitations of this study is that the apparatus used for blood pressure measurement was different in the two studies. This was inevitable since the apparatus used in first survey was unavailable at the time of the next survey. The two apparatus have marginal difference and if anything the current method of automated blood pressure monitors is known to underestimate blood pressure31 and thus the prevalence and shift in blood pressure levels in the population would only be higher. The other limitation is that behavioural risk factors like diet and physical activity were not assessed during the first survey and therefore not reported and they could account for difference in blood pressure levels as discussed. In addition, macro level changes in the population like socioeconomic transition, urbanisation, policy and so on are not accounted for in our study. The study being restricted to urban and rural NCR of Delhi may not be generalisable across India though similar prevalence rates have been reported across the country.

Conclusion

This two-time survey of NCR of Delhi shows marked increase in prevalence of hypertension in the last two decades both in rural and urban areas with higher rates of increase in younger age. This was also associated with fewer individuals with optimum blood pressure and more with prehypertension and hypertension. This calls for urgent population and high-risk approach to lower blood pressure in the community as the overall awareness, treatment and control levels showed no improvement over this time frame.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KSR, NT, DP, AK, DKS, MS and AR conceptualised and designed the study and revised the manuscript. KSR, DP, AK, PAP, RA and AR were involved in execution of the study in the field. PAP, DP and AR drafted and revised the manuscript. DK and KS did the data analysis. LR and RG coordinated the biochemical analysis and interpreted the data.

Funding: The study was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Ethics Committee, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Study data and additional explanatory materials will be shared with fellow researchers on request.

References

- 1. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Devi P, Rao M, Sigamani A, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and awareness of hypertension in India: a systematic review. J Hum Hypertens 2013;27:281–7. 10.1038/jhh.2012.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gupta R. Trends in hypertension epidemiology in India. J Hum Hypertens 2004;18:73–8. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Roy A. Cardiovascular Diseases in India. Circulation 2016;133:1605–20. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70151-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anchala R, Kannuri NK, Pant H, et al. Hypertension in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. J Hypertens 2014;32:1170–7. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:1903–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at Least 110 to 115 mm hg, 1990-2015. JAMA 2017;317:165 10.1001/jama.2016.19043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. United Nations. UN General Assembly resolution on the prevention and control of non communicable diseases. 2010. www.un.org (accessed 5 Mar 2014).

- 10. World Health Organization. NCD global monitoring framework. 2013. http://www.who.int/nmh/global_monitoring_framework (accessed 5 Mar 2014).

- 11. Prabhakaran D, Roy A, Praveen PA, et al. 20-Year trend of cardiovascular disease risk factors: urban and rural national capital region of Delhi, India. Glob Heart 2017. (Epub ahead of print). 10.1016/j.gheart.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72. 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013;22:278–95. 10.1177/0962280210395740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gupta R, Guptha S, Gupta VP, et al. Twenty-year trends in cardiovascular risk factors in India and influence of educational status. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;19:1258–71. 10.1177/1741826711424567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deepa M, Anjana RM, Manjula D, et al. Convergence of prevalence rates of diabetes and cardiometabolic risk factors in middle and low income groups in urban India: 10-year follow-up of the Chennai Urban Population Study. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011;5:918–27. 10.1177/193229681100500415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kishore J, Gupta N, Kohli C, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and determination of its risk factors in Rural Delhi. Int J Hypertens 2016;2016:1–6. 10.1155/2016/7962595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bansal SK, Saxena V, Kandpal SD, et al. The prevalence of hypertension and hypertension risk factors in a rural Indian community: A prospective door-to-door study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2012;3:117–23. 10.4103/0975-3583.95365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kini S, Kamath VG, Kulkarni MM, et al. Pre-Hypertension among Young adults (20-30 years) in Coastal villages of Udupi District in Southern India: an alarming scenario. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154538 10.1371/journal.pone.0154538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Hypertension 2008;52:818–27. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Menéndez E, Delgado E, Fernández-Vega F, et al. Prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and control of hypertension in Spain. results of the Di@bet.es Study. Rev española Cardiol 2016;69:572–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhadoria AS, Kasar PK, Toppo NA, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors in Central India. J Family Community Med 2014;21:29–38. 10.4103/2230-8229.128775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ali MK, Bhaskarapillai B, Shivashankar R, et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk in urban South Asia: the CARRS Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:408–19. 10.1177/2047487315580891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reddy KS, Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, et al. Educational status and cardiovascular risk profile in Indians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:16263–8. 10.1073/pnas.0700933104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Samuel P, Antonisamy B, Raghupathy P, et al. Socio-economic status and cardiovascular risk factors in rural and urban areas of Vellore, Tamilnadu, South India. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1315–27. 10.1093/ije/dys001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kar SS, Thakur JS, Virdi NK, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases: is the social gradient reversing in northern India? Natl Med J India 2010;23:206–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang X, Zhou Z, Liu J, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among China's Sichuan Tibetan population: A cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Hypertens 2016;38:457–63. 10.3109/10641963.2016.1163369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roy A, Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, et al. Impact of alcohol on coronary heart disease in indian men. Atherosclerosis 2010;210:531–5. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leong DP, Smyth A, Teo KK, et al. Patterns of alcohol consumption and myocardial infarction risk: observations from 52 countries in the INTERHEART case-control study. Circulation 2014;130:390–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 2013;310:959–68. 10.1001/jama.2013.184182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Irazola VE, Gutierrez L, Bloomfield G, et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in selected LMIC communities. Glob Heart 2016;11:47–59. 10.1016/j.gheart.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ostchega Y, Zhang G, Sorlie P, et al. Blood pressure randomized methodology study comparing automatic oscillometric and mercury sphygmomanometer devices: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009-2010. Natl Health Stat Report 2012:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015639supp001.pdf (272.6KB, pdf)