Abstract

Introduction

The present study is the largest registry study ever conducted in Japan exploring the prevalence of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) among patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Our study aims to (1) evaluate the status of lipid management and the subsequent risk of major cardiovascular events following hospitalisation of Japanese patients with ACS in real-world clinical practice; (2) determine the proportion of Japanese patients with ACS who achieve the lipid management goal and have a reduction of event risks with strict lipid management (low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol <1.81 mmol/L); (3) determine the prevalence of FH and (4) investigate the clinical significance of proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) level.

Methods and analysis

We will conduct a multicentre, prospective, observational study of approximately 2000 Japanese patients with ACS with/without FH hospitalised between April 2015 and August 2016. The primary end point is the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) after initial hospitalisation. The secondary end points are (1) MACE developed from visit 1 to visit 2 (day 30); (2) MACE developed from visit 2 (day 30) to visit 5 (day 730); (3) treatment rate by lipid-lowering therapies (any statin or intensive, PCSK9 inhibitor, fibrates and ezetimibe); (4) incidence of events by the addition of the following outcomes to the primary end point: coronary revascularisation due to myocardial ischaemia, revascularisation other than coronary artery, inpatient treatment for occurrence or exacerbation of heart failure, transient ischaemic attack, acute arterial occlusion, central retinal artery occlusion and other adverse events prolonging or requiring hospitalisation and (5) proportion of subjects achieving target lipid levels.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was submitted to the ethical review committee of each participating centre for approval. Participation in the study is voluntary and anonymous. The study findings will be disseminated in international peer-reviewed journals and presented at relevant conferences.

Clinical trial registration

UMIN000018946.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, familial hypercholesterolaemia, Japan, lipid management, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will provide new insights into the relationship between acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and recurrent events and the relationship between recurrent events and serum low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels in Japanese patients with ACS.

This study will be the first to evaluate the familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) to ACS ratio and will provide important information regarding proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) concentrations, including (1) the dynamic change of PCSK9 concentrations during post-ACS medical management, (2) the relationship between PCSK9 concentrations and cardiovascular events, (3) the difference of PCSK9 concentrations between FH and non-FH and (4) the relationship among PCSK9 concentrations, lipid parameters and lipid-lowering therapies for both statin-naïve and statin-exposed patients.

This study will be a prospective, large-scale, observational study of approximately 2000 Japanese patients with ACS from 59 participating centres.

This study is the largest FH registry study in Japan targeting the high-risk population.

This study will be limited by the inherent limitations of the observational study design (eg, susceptibility to biases and confounders, and the inability to establish causality) and the small sample size; the generalisability of our findings will be limited to the Japanese population.

Introduction

The incidence of atherosclerotic disease, including heart disease, in Japan is increasing and is associated with a change towards a Western lifestyle and increase in dyslipidaemia.1 There is a positive correlation between low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and the incidence of coronary artery disease.2 3 Therapy to lower LDL-C helps prevent cardiovascular events. Large statin trials have demonstrated the benefits of achieving an LDL-C level of 1.42–2.02 mmol/L, which has served as a basis for more aggressive European and US guidelines.4 In particular, aggressive therapy to achieve LDL-C <1.81 mmol/L, the target value for lipid management (in patients for whom aggressive therapy is intended) in European and US guidelines,5–7 or the use of high-intensity statins according to the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines have helped to reduce cardiovascular events and the progression of atherosclerosis.5–11

However, the Japanese guidelines for the prevention of atherosclerosis published in 2012 set higher target values for LDL-C management at <3.11 mmol/L in primary prevention for high-risk patients and <2.59 mmol/L for secondary prevention because the evidence for benefit was suggested to be insufficient.12 Previous Japanese studies (ESTABLISH and the follow-up Extended-ESTABLISH study) reported that aggressive LDL-C lowering reduced the incidence of death, the recurrence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and cerebral infarction compared with a control group.13 14 The MEGA study showed the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy in Japanese patients, but to values >2.59 mmol/L.15 While a number of imaging studies with intravascular ultrasound and other modalities have shown the benefits of aggressive LDL-C-lowering therapy in Japanese patients in terms of reduced plaque volume or coronary plaque regression,13 16–19 there is no large-scale clinical study that shows the need for aggressive lipid-lowering therapy in Japan, especially to LDL-C target values <2.59 mmol/L. It is generally accepted that insufficient evidence is available to determine the benefit of such therapy. Therefore, investigations into this issue, and evaluation of a possible relationship between LDL-C and recurrent coronary events and coronary artery disease progression in Japan are needed.

Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is an inherited, autosomal dominant disease resulting from abnormalities in the genes coding for the LDL receptor and related molecules. It is characterised by three major signs: (i) hyper-LDL-cholesterolaemia; (ii) early onset coronary artery diseases and (iii) tendon/skin xanthoma. Untreated FH carries an extremely high risk of developing coronary artery diseases, particularly in men aged between 30 and 50 years and women aged between 40 and 70 years.20 21 Risk data from the Simon Broome study in 1991 showed that the risk of cardiovascular death was 99 times higher in patients with FH at ages 20–39 years.22 Although heterozygous FH is present in an estimated 300 000 patients in Japan,23 the diagnosis rate is only <1% of the estimated number of patients with FH in Japan.21 According to an investigation by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan,20 the prevalence of FH is 4%–19% of patients presenting with ACS. FH may be underdiagnosed because of a masking effect by statin therapy, or the transient reduction of LDL-C associated with acute myocardial infarction. A prospective cohort observational study of 4534 patients with ACS in Switzerland reported an FH prevalence of 1.6%–5.5%, and a higher adjusted risk of coronary death or myocardial infarction among patients with FH than without (HR 2.46–3.53 after 1 year).24 To date, there have been no reports regarding the ACS recurrence rate in patients with FH in Japan. Therefore, it is important to clarify the prevalence of FH in patients with ACS, the recurrence rate of cardiovascular events in patients with FH and risk factors for recurrence to provide the optimal treatment for Japanese patients with FH.

Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) is a protein that binds to LDL receptors to induce their degradation in intracellular lysosomes and inhibit their recycling.25 Interestingly, patients with loss-of-function mutations in the PCSK9 gene have low LDL-C levels and rarely develop cardiovascular diseases compared with normal individuals. PCSK9 inhibitors are an effective lipid-lowering therapy. PCSK9 and LDL-C levels show a positive correlation in patients not treated with a lipid-lowering therapy, but this relationship disappears when lipid-lowering therapies, particularly oral statins, are administered.26 27 Statins may simultaneously increase the concentration of PCSK9 and the expression of LDL receptors, while lowering LDL-C.26 However, despite our current knowledge of PCSK9, its clinical significance in patients with ACS remains unclear. Considering the above-mentioned gaps in the literature, the primary objective of this study is to evaluate the status of lipid management and risk of major cardiovascular events in Japanese patients with ACS in real-world clinical practice. Secondary study objectives are to identify the proportion of patients with ACS in Japan who (i) achieve the target value of lipid management (LDL-C ≤2.59 mmol/L); (ii) have a reduction of event risks with strict lipid management (LDL-C <1.81 mmol/L) and (iii) have FH. The risk of recurrent ACS in patients with FH compared with patients without FH will be determined using the diagnostic criteria for FH as shown in box 1. Other objectives are to investigate the clinical significance of PCSK9 concentrations by observing the time-course profile of PCSK9 concentrations in patients presenting with ACS and analysing the relationship between the concentration of PCSK9 and FH, lipid-lowering therapy and lipid management levels.

Box 1. Diagnostic criteria for heterozygous FH in adults (aged 15 years and older)*.

Hyper LDL cholesterolaemia (LDL-C ≥180 mg/dL before treatment)

Tendon xanthoma (tendon xanthoma in the back of hand, elbow, knee, etc or Achilles tendon hypertrophy) or xanthoma tuberosum

Family history (blood relatives within the second degree of kinship) of FH or early onset coronary artery disease

Notes

Diagnosis is established excluding secondary hyperlipidaemia.

FH is diagnosed when two or more items are met. Diagnosis by genetic examination is advised if FH is suspected.

Tuberous xanthoma does not include xanthelasma of the eyelid.

Achilles tendon hypertrophy is diagnosed by a thickness of ≥9 mm on soft X-ray imaging.

FH is strongly suspected if LDL-C is ≥250 mg/dL.

If the patient is already on drug therapy, refer to the lipid level that triggered the treatment.

Early onset coronary artery diseases are defined as those in which onset occurs at <55 years of age in men and <65 years of age in women.

*Reproduced with modifications from Harada-Shiba et al 20 with permission from the Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis.

FH, familial hypercholesterolaemia; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This will be a multicentre, prospective, observational study of Japanese patients presenting with ACS. Sixty-five sites are planned to participate in this study (see online supplementary appendix). These sites were chosen based on their ability to provide the most advanced percutaneous coronary intervention in Japan for patients presenting with ACS. Consecutive patients requiring hospitalisation for ACS were registered in 59 sites, for a total of 2016 patients, between April 2015 and August 2016.

bmjopen-2016-014427supp001.docx (32.2KB, docx)

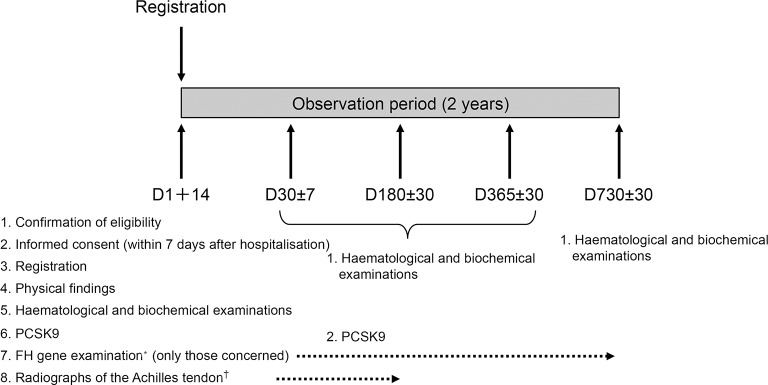

After the patients provided written informed consent within 7 days after hospitalisation for ACS, the investigator at each study centre successively registered subjects who met the inclusion criteria. Successive registration of patients limits the selection bias by the investigator. The schedule for initial and follow-up examinations and the data to be collected are shown in figure 1 and table 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow and design. *For FH gene examination, blood will be collected once from the patients who provide consent, at a visit made after registration. †Radiographs of the Achilles tendon will be obtained during hospitalisation for registration as a rule, but a radiography obtained by visit 3 is acceptable. FH, familial hypercholesterolaemia; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9.

Table 1.

Observations and end points

| Category | Method and materials | Observation and examination items |

| Demographic characteristics (subjects’ background) | Interview | Age, sex and smoking and drinking status |

| ACS | Medical examination and interview | Onset date of ACS, date of hospitalisation, disease type, description of treatment |

| History of present illness/previous history/therapies | Interview | Particular previous history of cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular risk-related diseases and history of their treatments (immediately before hospitalisation and at each visit) |

| Physical findings | Medical examination | Body height, body weight and presence or absence of xanthoma |

| Reference LDL-C value | Interview | Value before treatment such as that obtained at a health examination |

| Family history | Interview | Coronary artery diseases, ischaemic cerebral infarction and hypercholesterolaemia in relatives to the second degree of kinship |

| Primary end points | Interview | Investigation of outcome (alive or dead), date of death, cause of death and presence or absence of non-fatal ACS and non-fatal cerebrovascular diseases requiring in-hospital treatments |

| Secondary end points | Interview | Presence or absence of event |

| Haematological and biochemical examinations | Serum | The following parameters will be measured from blood obtained in the sitting position when the symptoms are stable: Total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol (automatic calculation), triglycerides, apoA1, apoB, Lp(a), creatinine, blood glucose, HbA1c, hsCRP, haemoglobin and haematocrit |

| PCSK9 | Serum | Collective measurement at the central laboratory |

| FH gene examination | Whole blood | Collective measurement at the central laboratory |

| Radiography of the Achilles tendon* | Radiography | Whenever possible, radiography of the Achilles tendon will be performed during index hospitalisation for registration, but radiography obtained by visit 3 will also be acceptable |

*Radiography of the Achilles tendon was performed based on the recommendation of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society FH guidelines.20

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9; apo, apolipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; Lp(a), lipoprotein A; FH, familial hypercholesterolaemia.

Data are collected at visit 1 (within 14 days after hospitalisation due to ACS), and visits 2–5 during the 2-year observational period on days 30 (±7 days), 180 (±30 days), 365 (±30 days) and 730 (±30 days). Data are collected using an electronic case report form. The information collected at each visit is shown in table 1. During the 2-year observation period (visits 2–5), if a subject is transferred to another hospital during this time, the institution will be asked to provide the following information for the follow-up: attendance/non-attendance; date of observation; primary end points (investigation of outcome (alive/dead)); secondary end points (presence or absence); physical examination; fasting haematological and biochemical examinations, including PCSK9 concentrations (visits 2–4) and medications.

The samples collected in this study will be sent to a central laboratory (BML General Laboratory, Saitama, Japan) under freezing conditions (−20°C) until completion of the study so that re-examination can be performed. All samples will be discarded after completion of the study.

Study subjects

The study subjects are Japanese patients presenting with ACS, hospitalised between April 2015 and August 2016. In total, 2016 subjects were registered.

The key inclusion criteria are as follows: age ≥20 years; hospitalisation for any ACS including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina; and ability to obtain written informed consent. STEMI is defined as the presence of chest symptoms such as pain or breathlessness suspected to be caused by myocardial ischaemia, persisting for ≥20 min; ST elevation of ≥1 mm on ≥2 contiguous leads or new left bundle branch block and elevated troponin T≥0.1 µg/L or creatine phosphokinase-MB two times above the upper limit of normal. Acute NSTEMI is defined as the presence of chest symptoms such as pain or breathlessness suspected to be caused by myocardial ischaemia, persisting for ≥20 min ≤24 hours before admission; not having ST-segment elevation ≥1 mm or new left bundle branch block and the presence of elevated troponin T≥1.0 µg/L or creatine phosphokinase-MB two times above the upper limit of normal. Unstable angina is defined as the presence of chest pain that may be persistent (≥20 min) and at least one of the following: ST depression ≥0.5 mm or T-wave inversion ≥3 mm; troponin T≥0.014 or <1.0 µg/L; confirmation of significant stenosis by diagnostic imaging; new decrease in wall motion detected by echocardiography or reversible myocardial perfusion defect detected by myocardial perfusion imaging.

The key exclusion criteria are as follows: patients with chest pain and coronary artery diseases presenting with concomitant serious diseases, patients with in-stent thrombosis, patients enrolled in other interventional studies that could affect lipid profile and those judged as inappropriate by the investigators or subinvestigators.

Primary end point

The primary end point is the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as death associated with myocardial infarction or other cardiovascular death, major non-fatal coronary event (myocardial infarction or hospitalisation for unstable angina) or stroke. Incidences are monitored independently by the investigator at each local site. A time window will be allowed for observations at visit 2 (±7 days) and visits 3–5 (±30 days).

Deaths associated with myocardial infarction or other cardiovascular deaths are defined as death secondary to acute myocardial infarction or any death with a clear relationship to underlying coronary heart disease, sudden death, heart failure, complication of coronary revascularisation procedure where the cause of death is clearly related to the procedure, unobserved or unexpected death or other death that cannot be definitively attributed to a non-cardiovascular cause. Non-fatal myocardial infarction is defined in accordance with the ACC/AHA/European Society of Cardiology Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.28

Ischaemic stroke is characterised by an acute episode of focal cerebral, spinal or retinal dysfunction caused by infarction, defined by at least one of the following: pathological, imaging or other objective evidence of acute, focal cerebral, spinal or retinal ischaemic injury in a defined vascular distribution; symptoms of acute cerebral, spinal or retinal ischaemic injury persisting for ≥24 hours or until death, with other aetiologies excluded.

Secondary end points

The secondary end points are MACE developed from visit 1 to visit 2 (day 30); MACE developed from visit 2 (day 30) to visit 5 (day 730); treatment rate by the following lipid-lowering therapies: any statin, intensive statin (eg, atorvastatin ≥20 mg, rosuvastatin ≥10 mg and pitavastatin ≥4 mg), PCSK9 inhibitor, and other lipid-lowering therapies such as fibrates and ezetimibe; incidence of events by the addition of the following outcomes to the primary end points: coronary revascularisation due to myocardial ischaemia, revascularisation other than in the heart, inpatient treatment for occurrence or exacerbation of heart failure, transient ischaemic attack, acute arterial occlusion, central retinal artery occlusion and other adverse events prolonging or requiring hospitalisation and proportion of subjects achieving target lipid levels per study visit. The treatment rate will be determined based on written prescriptions. Other end points include the prevalence of FH in patients with ACS, comparison of PCSK9 concentration between patients with or without FH and comparison between clinical diagnosis of FH based on the guidelines versus genetic analysis.

Discontinuation from study

The criteria used to allow discontinuation from the study include the withdrawal of consent by the subject or his/her legal representative, patient ineligibility (violation of the study contract), death of a subject or removal by the judgement of the investigator or subinvestigators.

Safety protocol

Because this is an observational study (ie, non-interventional), there will be no adverse events caused by a study drug. Patients will receive drugs as normally prescribed in daily medical practice.

Serious adverse drug reactions caused by a drug will be the subject for application of relief under the Relief System for Sufferers from Adverse Drug Reactions similar to that in daily medical practice. Treatments for other adverse drug reactions will be covered by the national insurance scheme.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was calculated to assess the persistent cardiovascular risk (defined as MACE) from the index event to 2 years. Based on the PACIFIC registry, in which the incidence of MACE was 6.4% at 2 years, a sample size of 2000 has a precision of ±1% in the incidence of MACE with a 95% CI of 0.053 to 0.074.29 With this sample size, the subgroup analysis (the comparison of MACE in patients with LDL-C <1.81 mmol/L and ≥1.81 mmol/L) will be performed. Because 409 of 1827 (22.3%) Japanese patients with ACS in the PACIFIC study and 305 of 1145 (26.6%) Japanese patients with ACS in an ongoing database study reached an LDL-C level <1.81 mmol/L, we expect to have 446–532 patients with an LDL-C level <1.81 mmol/L in this registry. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria will be analysed. The demographic data will be presented as the mean, median, SD and range for continuous data, and number and proportion of subjects in each category for categorical data.

The analysis of the primary end point will be as follows: for the incidence of MACE at 2 years, Kaplan-Meier analysis will be used to estimate the event observed first after registration in the whole population. The Greenwood formula will determine the 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis will investigate the association of factors with the incidence of MACE, LDL-C <1.81 mmol/L vs ≥1.81 mmol/L at registration and the presence or absence of FH. The Cox proportional hazard model and subgroup analysis will compare demographic factors (age, sex, smoking history, body mass index and underlying diseases) using a two-sided significance level of 5% (not considering multiplicity, as the study is exploratory). Subgroup analysis will be performed for LDL-C (<1.81 or ≥1.81 mmol/L) at the time when the event has occurred.

Analysis of the secondary end points (MACE developed by visit 2 (day 30); MACE developed between visit 2 (day 30) and visit 5 (day 730) and treatment rate by lipid-lowering therapy) will be assessed by determining the ratio of subjects on each lipid-lowering therapy administered during observation and the 95% CI using the full analysis set. The incidences of events at visit 2 and between visits 2 and 5 or from the time of registration to the first event, and the associations of factors with each event will be determined by the same procedures as for the primary end points. For the other end points, the prevalence rate of FH in patients with ACS will be assessed and its 95% CI from the diagnosis of FH will be determined. Logistic regression analysis and subgroup analysis of the background factors that are associated with the prevalence of FH for exploratory investigation will be determined. The summary statistics for the concentration of PCSK9 at each measurement point will be calculated and a trend diagram (median values) will be developed. In addition, the presence or absence of the influence of FH by subgroup analysis will be determined.

In the survival analysis, missing values will be censored while continuous data and discrete data will be analysed on the basis of measured values without performing any special processing. Furthermore, we will also perform a sensitivity analysis where continuous data are handled using the last observation carried forward imputation, and discrete data are included only in the denominator but not in the numerator. No special processing will be performed for outliers. For the statistical analysis, SAS V.9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) will be used.

Quality assurance measures

The study investigators will ensure compliance with the study protocol. Any change in factors that affect the safety of subjects or the scientific quality of this study (study design, end points, number of patients and criteria for registration) will require a revision of the protocol, which must be approved in advance by the ethical review committee. The study records will be stored and information made available to auditors, ethical review committees or regulatory authorities on request.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (amended in October 2013) and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects (enacted on 22 December 2014). Prior to the study initiation, the investigator or subinvestigators submitted the protocol and informed consent form to the ethical review committee of each study centre and obtained their approval. Patient anonymity will be protected by the use of subject identification codes. A cooperation fee of 5000 Japanese yen (about US$42 or €37 in October 2015) for study participation will be provided for each patient on request from the study centre. All patients were required to provide written informed consent.

The results of this study will be presented at major cardiovascular-related congresses. The data regarding FH will be presented at atherosclerotic-related congresses.

Conclusion

The EXPLORE-J study will provide new insights into the relationship between ACS and recurrent events, the relationship between recurrent events and serum LDL-C levels, the FH to ACS ratio and the PCSK9 concentration in patients with ACS in a Japanese population. As a large-scale study including 2016 patients from 59 centres, this study will be the first ACS registry to seek insight into FH in Japan to target the high-risk population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marion Barnett, J Ludovic Croxford, PhD and Michelle Belanger, MD of Edanz Group for providing medical writing support; Tamio Teramoto of Teikyo University (Tokyo, Japan), Shun Ishibashi of Jichi Medical University (Tochigi, Japan), Kotaro Yokote of Chiba University (Chiba, Japan), Tomonori Okamura of Keio University (Tokyo, Japan) and Hiroyuki Daida of Juntendo University (Tokyo, Japan) for collaboration and advice regarding planning of the study; Yosuke Ujike and Yasuyoshi Nakahigashi of Sanofi (Tokyo, Japan) for providing writing and editing support; Mebix (Tokyo, Japan) for assistance with study implementation/operation; BML (Tokyo, Japan) for proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9-related and genome-related analysis; CTD. (Tokyo, Japan) for consulting and Shizuya Yamashita of Rinku General Medical Center (Osaka, Japan), Toru Yoshizumi of Kawasaki Hospital (Hyogo, Japan), and Micron (Tokyo, Japan) for radiography of the Achilles tendon.

Footnotes

Early statin treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome: demonstration of the beneficial effect on atherosclerotic lesions by serial volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis during half a year after coronary event.

Contributors: MN, KU, AH, JA, AN, HA and MH-S all served on the steering committee as principal investigators and equally contributed to conception and design of the study, protocol development, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting and revising the publication for important intellectual content. MN, KU, AH, JA, AN, HA and MH-S approved the final version of the manuscript and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: KU is an employee of Sanofi. MN, AH, JA, AN, HA and MH-S have received consultation fees from Sanofi.

Ethics approval: The ethical review committee of each study centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data is available.

References

- 1. Iso H. Lifestyle and cardiovascular disease in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb 2011;18:83–8. 10.5551/jat.6866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gotto AM. Jeremiah Metzger lecture: cholesterol, inflammation and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: is it all LDL? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2011;122:256–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1670–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program adult treatment panel III guidelines. Circulation 2004;110:227–39. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G, et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2011;32:1769–818. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016;2016:2999–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Keefe JH, Cordain L, Harris WH, et al. Optimal low-density lipoprotein is 50 to 70 mg/dl: lower is better and physiologically normal. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2142–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1425–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa050461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;2014:S1–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, et al. Executive summary of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guidelines for the diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Japan -2012 version. J Atheroscler Thromb 2013;20:517–23. 10.5551/jat.15792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okazaki S, Yokoyama T, Miyauchi K, et al. Early statin treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome: demonstration of the beneficial effect on atherosclerotic lesions by serial volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis during half a year after coronary event: the ESTABLISH Study. Circulation 2004;110:1061–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140261.58966.A4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dohi T, Miyauchi K, Okazaki S, et al. Early intensive statin treatment for six months improves long-term clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome (Extended-ESTABLISH trial): a follow-up study. Atherosclerosis 2010;210:497–502. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakamura H, Arakawa K, Itakura H, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in Japan (MEGA Study): a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006;368:1155–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69472-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hiro T, Kimura T, Morimoto T, et al. Effect of intensive statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a multicenter randomized trial evaluated by volumetric intravascular ultrasound using pitavastatin versus atorvastatin (JAPAN-ACS [Japan assessment of pitavastatin and atorvastatin in acute coronary syndrome] study). J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:293–302. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takayama T, Hiro T, Yamagishi M, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin on coronary atheroma in stable coronary artery disease: multicenter coronary atherosclerosis study measuring effects of rosuvastatin using intravascular ultrasound in Japanese subjects (COSMOS). Circ J 2009;73:2110–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakajima N, Miyauchi K, Yokoyama T, et al. Effect of combination of ezetimibe and a statin on coronary plaque regression in patients with acute coronary syndrome. IJC Metab Endocr 2014;3:8–13. 10.1016/j.ijcme.2014.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsujita K, Sugiyama S, Sumida H, et al. Impact of dual lipid-lowering strategy with ezetimibe and atorvastatin on coronary plaque regression in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: the Multicenter Randomized Controlled PRECISE-IVUS Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:495–507. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harada-Shiba M, Arai H, Okamura T, et al. Multicenter study to determine the diagnosis criteria of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb 2012;19:1019–26. 10.5551/jat.14159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3478–90. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Risk of fatal coronary heart disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Scientific Steering Committee on behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. BMJ 1991;303:893–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tada N, Yoshida H, Teramoto T, et al. Investigation on risk factors in patients with high LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol and treatment on hyperlipidaemia in Japan—Lipid Management Program (LiMAP) in Japan—[in Japanese]. J Adult Dis 2005;35:1187–97. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nanchen D, Gencer B, Muller O, et al. Prognosis of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2016;134:698–709. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roth EM, Diller P. Alirocumab for hyperlipidemia: physiology of PCSK9 inhibition, pharmacodynamics and phase I and II clinical trial results of a PCSK9 monoclonal antibody. Future Cardiol 2014;10:183–99. 10.2217/fca.13.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raal F, Panz V, Immelman A, et al. Elevated PCSK9 levels in untreated patients with heterozygous or homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and the response to high-dose statin therapy. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000028 10.1161/JAHA.112.000028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guo Y-L, Zhang W, Li J-J, et al. PCSK9 and lipid lowering drugs. Clinica Chimica Acta 2014;437:66–71. 10.1016/j.cca.2014.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2551–67. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miyauchi K, Morino Y, Tsukahara K, et al. The PACIFIC (Prevention of AtherothrombotiC Incidents Following Ischemic Coronary attack) Registry: rationale and design of a 2-year study in patients initially hospitalised with acute coronary syndrome in Japan. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2010;24:77–83. 10.1007/s10557-010-6223-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014427supp001.docx (32.2KB, docx)