Abstract

Objective

Better knowledge of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prevalence at the national level can help to implement pertinent strategies to address HBV related burden. The aim was to estimate the seroprevalence of HBV infection in Cameroon.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Participants

People residing in Cameroon.

Data sources

Electronic databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, African Journals Online (AJOL), ScienceDirect, WHO-Afro Library, WHO-IRIS, African Index Medicus, National Institute of Statistics and National AIDS Control Committee, Cameroon; regardless of language and from 1 January 2000 to 30 September 2016. This was completed with a manual search of references of relevant papers. Risk of bias in methodology of studies was measured using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Results

Out of 511 retrieved papers, 44 studies with a total of 105 603 individuals were finally included. The overall pooled seroprevalence was 11.2% (95% CI 9.7% to 12.8%) with high heterogeneity between studies (I 2=97.9%). Egger’s test showed no publication bias (p=0.167). A sensitivity analysis excluding individuals at high risk of HBV infection and after adjustment using trim and fill method showed a pooled seroprevalence of 10.6% (95% CI 8.6% to 12.6%) among 100 501 individuals (general population, blood donors and pregnant women). Sources of heterogeneity included geographical regions across country and setting (rural 13.3% vs urban 9.0%), and implementation of HBV universal immunisation (born after 9.2% vs born before 0.7%). Sex, site, timing of data collection, HBV screening tools and methodological quality of studies were not sources of heterogeneity.

Limitation

Only a third of the studies had low risk of bias in their methodology.

Conclusion

The seroprevalence of HBV infection in Cameroon is high. Effective strategies to interrupt the transmission of HBV are urgently required. Specific attention is needed for rural settings, certain regions and people born before the implementation of the HBV universal immunisation programme in Cameroon in 2005.

Registration

PROSPERO, CRD42016042654.

Keywords: Prevalence, hepatitis B, Cameroon, Africa, HBV, hepatitis B virus

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that focuses on hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Cameroon.

This review included more studies compared with previously published global meta-analysis; in addition, the prevalence for specific populations were estimated; and the difference between sex, geographical regions, HBV screening tools, status regarding implementation of HBV universal immunisation programme and residence areas were assessed.

Strong methodological and statistical procedures were used.

Across studies, HBV screening tools and their sensitivity and specificity may be different; this may influence estimates.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global public health problem affecting millions of people every year and causing disability and death.1 Globally, it is estimated that approximatively 257 million people are infected, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries.2 3 About 1 million people die each year (~2.7% of all deaths) from causes related to viral hepatitis, mostly liver disease, including liver cancer and cirrhosis.1 4 In highly endemic areas, hepatitis B is most commonly spread from mother to child at birth (perinatal transmission), or through horizontal transmission (exposure to infected blood), especially from an infected child to an uninfected child during the first 5 years of life.2 5 An estimated 50% to 80% of cases of primary liver cancer result from infection with HBV.6 In sub-Saharan Africa, infections by HBV affect between 5% and 10% of the population. In many countries, HBV infection is the leading cause of liver transplants. The economic load of the disease is also important; in the terminal stage, treatments are expensive, the cost easily reaching hundreds of thousands of dollars per person.7

Following a global summit in 2015, WHO launched the global programme against hepatitis with the following goals, by 2030, to reduce by 90% the number of new cases of hepatitis B, reduce by 65% the number of hepatitis B-related deaths and treat 80% of eligible people infected with hepatitis B.8 The systematic review and meta-analysis published in Lancet by Schweitzer and colleagues in 2015 provides the global prevalence of HBV with estimate by countries.9 However, details on the source of data for each country are not provided, and the review gives an overall estimate of the prevalence, without emphasis on specific populations, especially at-risk groups to which interventions should be mostly directed. Therefore, the purpose of our review is to provide a detailed summarisation of the data on the prevalence of HBV in the general Cameroonian population, and specific populations such as blood donors, pregnant women and healthcare workers in particular. We strongly believe such detailed data are more likely to influence decision-making towards intervention to curb the burden of HBV in Cameroon.

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of data in populations residing within Cameroon as reported in studies published to determine the prevalence of HBV infection.

Methods

This review was reported following the PRISMA guidelines.10 The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses checklist can be found in online supplementary file S1. This review was registered in PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews, registration number CRD42016042654. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines were used as reference for the methodology of this review.11

bmjopen-2016-015298supp001.pdf (192.9KB, pdf)

Setting

Cameroon is a Central African country situated slightly above the equator. It covers a surface area of 472 650 km² divided into 10 administrative regions: Littoral, Far-North, North, Adamawa, North-West, South-West, West, East, South and Centre where the capital city (Yaoundé) is located. Cameroon counted 22.25 million inhabitants in 2013.12 The HBV universal immunisation programme was introduced in Cameroon in 2005. In Cameroon, for children born in 2005 or later, HBV vaccination is free of charge throughout the expanded programme on immunisation. In this vaccine programme, children receive three HBV vaccine doses at 6 weeks, 10weeks and 14 weeks of life. Beside this programme, the vaccine is not free of charge for the general population and was not free of charge for children born before 2005. The circulation of three HBV genotypes A, E and D was reported in patients in Cameroon, however, genotypes A and E are predominantly found.13–15

Criteria for considering studies for the review

Inclusion criteria

We considered cross-sectional, case-control or cohort studies of participants residing in Cameroon reporting the prevalence of HBV infection, or enough data to compute this estimate.

HBV infection diagnosed based on the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen.

Exclusion criteria

Studies conducted among Cameroonian populations residing outside Cameroon.

Studies not performed in humans.

Studies in subgroups of participants selected on the basis of the presence of any other viral hepatitis.

Case series, reviews, commentaries and editorials.

Studies lacking primary data and/or explicit method description.

Duplicates (for studies published in more than one report, the most comprehensive and up-to-date version was used).

Search strategy used to identify relevant studies

The search strategy was implemented in two stages:

We performed a comprehensive search of databases to identify all relevant articles published on HBV infection in Cameroon from 1 January 2000 to 31 September 2016 without language restriction. A systematic search of PubMed/MEDLINE, African Journals Online, Science Direct, WHO Afro Library, WHO Institutional Repository for Information Sharing, African Index Medicus, National Institute of Statistics, Cameroon (http://www.statistics-cameroon.org/), National AIDS Control Committee, Cameroon (http://www.cnls.cm/), and Health Sciences and Diseases (the biomedical journal of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaoundé 1, Cameroon) was undertaken using a predefined strategy based on the combination of relevant terms. We used both text words and medical subject heading terms; for example, ‘viral hepatitis B’, ‘hepatitis virus B’, ‘HBV’ and ‘Cameroon’. These terms and their variants were used in varying combinations. The literature search strategy was adapted to suit each database. The main search strategy conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE is shown in online supplementary file S2. The last search was conducted on 17 October 2016.

We manually searched the reference lists of eligible articles and relevant reviews.

bmjopen-2016-015298supp002.pdf (233.6KB, pdf)

Selection of included studies

Two investigators independently identified articles and sequentially screened their titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full texts of articles deemed potentially eligible were acquired. These investigators further independently assessed the full text of each study for eligibility, and consensually retained studies to be included. Disagreement was solved by a third investigator and discussion among authors. We used a screening guide to ensure that the selection criteria were reliably applied by all assessors.

Appraisal of the quality of included studies

An adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the methodological quality of studies included in this review.16 This scale was also used to assess the risk of bias affecting study findings. The NOS is formulated by a star allocation system, assigning a maximum of nine stars for the risk of bias in three areas: selection of study groups, comparability of groups and ascertainment of the outcome of interest. There is no validation study that provides a cut-off score for rating low-quality studies; a priori, we arbitrarily established that zero to three stars, four to six stars and seven to nine stars would be considered at high, moderate and low risk of bias, respectively.

Data extraction and management

One investigator extracted data regarding general information (authors, year, regions in Cameroon, type of publication), study characteristics (study design, setting, sample size, mean or median age, age range, proportions of male participants, diagnosis criteria for hepatitis B, disease specific/profile specific to the study population) and prevalence of hepatitis B. We considered two main groups of populations regarding their a priori risk to HBV infection: low-risk population (general population, blood donors and pregnant women) and high-risk population (HIV-infected people, haemodialysis patients, patients with sickle cell disease, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, and healthcare workers). Where only primary data (sample size and number of cases) were available, these were used to calculate the prevalence estimate. Where prevalence rates or relevant data for estimating them were not available, we contacted the corresponding author of the study to request the missing information. In the absence of response or no availability of full data, the corresponding study was excluded. A second investigator double-checked extracted data for accuracy.

Data synthesis including assessment of heterogeneity

Using meta-analysis, prevalence data were summarised by specific populations. Standard errors for the study-specific estimates were determined from the point estimate and the appropriate denominators, assuming a binominal distribution. We pooled the study-specific estimates using a random-effects meta-analysis model to obtain an overall summary estimate of the crude prevalence across studies, after stabilising the variance of individual studies with the use of the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation.17 A sensitive analysis was conducted excluding populations at high risk of HBV infection: healthcare workers, HIV-infected people, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and patients with sickle cell disease. Heterogeneity was assessed using the χ 2 test on Cochran’s Q statistic18 and quantified by calculating the I2.19 Values of 25%, 50% and 75% for I2 represent, respectively, low, medium and high heterogeneity. Where substantial heterogeneity was detected, when possible, we performed subgroup analysis to investigate the possible sources of heterogeneity using the following grouping variables: sex, study setting, study site, geographical region in Cameroon, status regarding implementation of the HBV universal immunisation in Cameroon, HBV screening tools and study methodological quality. Only populations at low risk of HBV infection were considered for these subgroup analyses. We assessed the presence of publication bias using funnel plots and the formal Egger’s test.20 A p value <0.10 was considered indicative of statistically significant publication bias. In addition, we conducted a trim and fill adjusted analysis to remove the most extreme small studies from the positive side of the funnel plot, re-computing the effect size at each iteration, until the funnel plot is symmetrical about the (new) effect size.21 We assessed inter-rater agreement for study inclusion using Cohen’s κ coefficient.22 Data were analysed using the statistical software STATA V.13.0 for Windows (Stata, 2013; Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Study selection

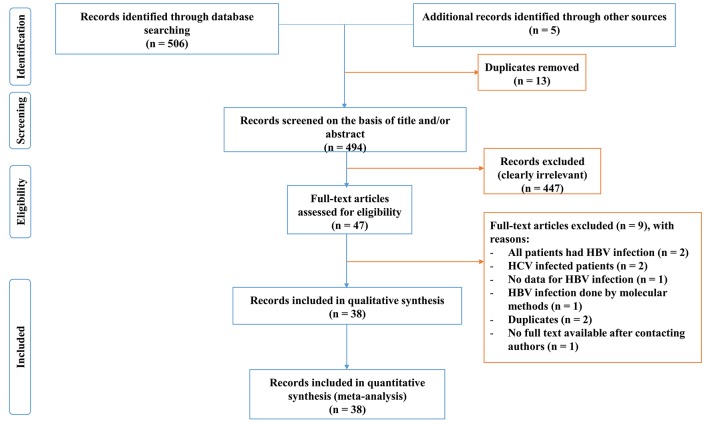

Initially, a total of 511 articles were identified. After elimination of duplicates, screening titles and abstracts, 460 papers were found irrelevant and excluded. Agreement between investigators on abstract selection was high (κ=0.88, p<0.001). Full texts of the remaining 47 papers were scrutinised for eligibility, among which 9 were excluded (figure 1).23–30 Overall, 38 papers including 44 studies were found eligible; hence they were included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Process of identification and selection of studies for inclusion in the review. HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of each included study are presented in online supplementary file S3. The 38 included papers were published from 2001 to 2016 and included studies conducted from 1994 to 2015 in the 10 regions of Cameroon.13 31–67 Twelve studies were conducted among blood donors,33 35 36 40 45 48–50 56 59 66 10 among pregnant women,13 31 32 34 35 37 39 44 47 48 58 60 61 64 8 among HIV-infected people,46 48 67 6 in the general population,41 51 55 57 63 65 4 among healthcare workers,42 48 54 62 1 among haemodialysis patients,43 1 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma,55 1 for HIV-infected pregnant women44 and 1 in patients with sickle cell disease.53 The age of included subjects varied from 1 year to 82 years. Three studies were population-based,41 51 57 39 were hospital-based13 31–40 42–50 52–56 58–64 66 67 and 2 studies did not report the setting.60 65 Eight studies were conducted solely in rural areas,13 41 48 58 67 22 in urban areas only,33 36 40 43 44 46 47 49 50 52–57 62–64 66 and 14 in both urban and rural.31 32 35 37 38 42 51 52 59–61 65 One study included only men,57 11 only women13 31 32 34 35 37 39 44 48 52 58 and 32 both sexes.33 36 38 40–43 45–47 49–51 53–56 59–68 Concerning diagnostic test used in studies, 22 were a rapid diagnostic test,13 32–36 38 40 45 48 49 53 54 56 58 59 61 62 65–67 9 were an enzyme linked immunoassay test,37 41–44 47 52 57 64 5were enzyme immunoassay test,31 39 46 60 63 1 was a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay and 7 studies not described in detail diagnostic tests.40 45 50 51 55

bmjopen-2016-015298supp003.pdf (271.9KB, pdf)

Methodological quality of studies

Fifteen (32.6%) studies had low,33 34 37 40 41 44 45 52 53 56–59 6719 (41.3%) moderate13 31 32 35 36 39 42 43 46 49 50 54 55 60 62 65 66 and 10 (26.1%)38 47 48 51 61 63 64 high risk of bias in their methodological quality. One paper was case control,55 10 studies were analysis of retrospective data33 38 40 45 47 59 60 67 and 33 studies were cross-sectional studies13 31 32 34–37 39 41–44 46 48–54 56–58 61–66 (see online supplementary file S3).

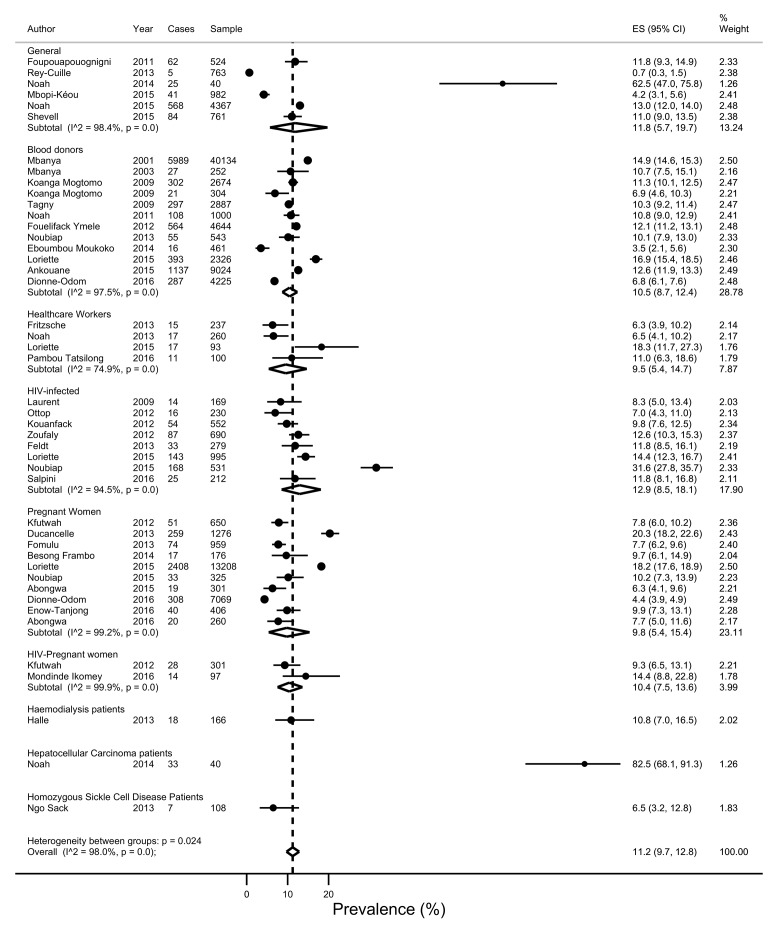

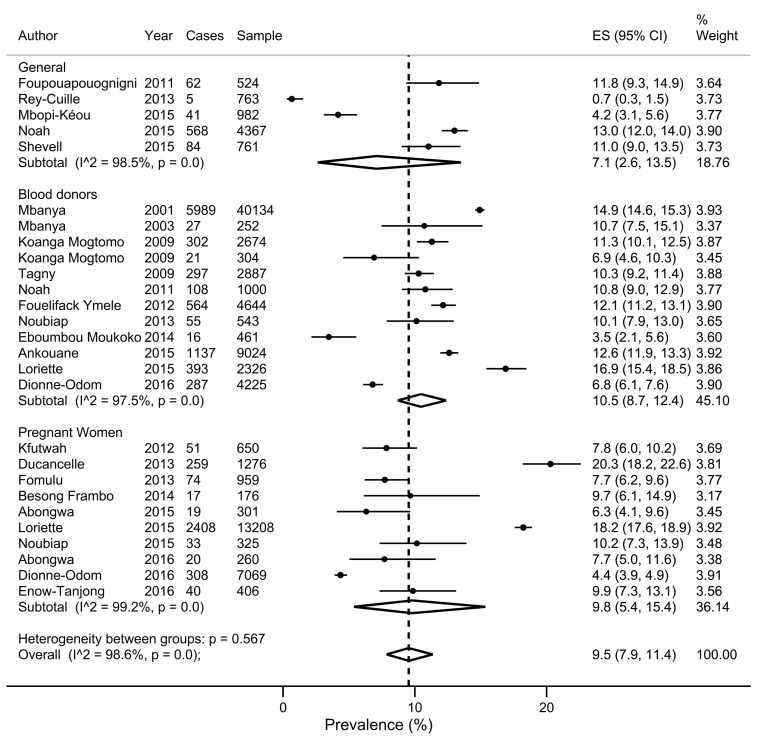

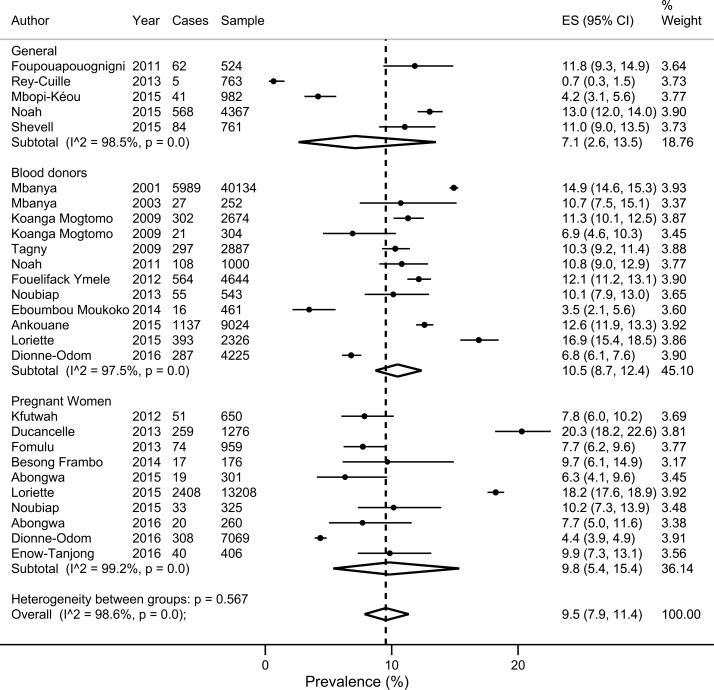

Overall pooled prevalence of HBV infection

There was a wide variation in HBV infection prevalence (figure 2). The crude overall prevalence of HBV infection in the pooled sample of 105 601 individuals was 11.2% (95% CI 9.7% to 12.8%). The sensitive overall pooled prevalence was also 9.5% (95% CI 7.9% to 11.4%) in a pooled sample of 100 501 individuals at low risk of HBV infection (figure 3). As expected, the prevalence of HBV infection (17.3, 95% CI 12.2 to 23.1) was higher in a population at high risk of HBV infection (p-difference=0.008) (figure 4). The heterogeneity between studies were high in both crude (I 2=98.0%, p-heterogeneity <0.001) and sensitive (I 2=98.6%, p-heterogeneity <0.001) meta-analyses. For the overall crude prevalence, funnel plot suggested publication bias (see online supplementary file S4) but the results of Egger’s regression test did not confirm any publication bias (p=0.167). For the sensitive overall prevalence, funnel plot suggested publication bias (see online supplementary file S5) confirmed by the results of Egger’s regression test (p=0.017). The adjusted sensitive HBV infection prevalence on trim and fill method was 10.6% (95% CI 8.6% to 12.6%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in all subpopulations in Cameroon.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in subpopulations at low risk in Cameroon.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in Cameroon by risk status.

bmjopen-2016-015298supp004.pdf (5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015298supp005.pdf (4.5KB, pdf)

Source of heterogeneity and subgroup analysis

Table 1 presents the HBV prevalence of all subgroups including assessment of heterogeneity, assessment of publication bias and assessment of difference between subgroups. Source of heterogeneity included regions in Cameroon (p-difference <0.001), settings (p-difference=0.001) and status regarding implementation of the HBV universal immunisation (p-difference <0.001). Results from meta-analysis suggested that the prevalence of HBV infection is higher in the North region and rural settings and lower in the West region and urban settings. The prevalence of HBV infection was also higher in people whose samples were collected before implementation of the HBV universal immunisation programme. There was no difference on pooled prevalence between subgroups of the population at low risk of HBV infection (general population, blood donors and pregnant women) (p-difference=0.567). Also, sex, study sites, timing of data collection, HBV screening tools and methodical quality of studies were not sources of heterogeneity (p-difference >0.05). The publication bias was found for all group analyses except for sex and HBV screening tools.

Table 1.

Summary statistics from meta-analyses of prevalence studies on hepatitis B virus infection among populations in Cameroon using random effects model and arcsine transformations

| Group | #Studies | #Participants | #Cases | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | I², % | p-heterogeneity | p-Egger's test | p-difference |

| Populations | ||||||||

| Overall | 27 | 100 501 | 13 185 | 9.5 (7.9 to 11.4) | 98.6 | <0.001 | 0.017 | 0.567 |

| General | 5 | 7397 | 760 | 7.1 (2.6 to 13.5) | 98.5 | <0.001 | ||

| Blood donors | 12 | 68 474 | 9196 | 10.5 (8.7 to 12.4) | 97.5 | <0.001 | ||

| Pregnant women | 10 | 24 630 | 3229 | 9.8 (5.4 to 15.4) | 99.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Regions | ||||||||

| Overall | 30 | 96 134 | 12 617 | 9.2 (7.1 to 11.5) | 97.9 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Centre | 10 | 60 372 | 8258 | 9.1 (7.1 to 11.3) | 97.5 | <0.001 | ||

| East | 1 | 364 | 37 | 10.2 (7.5 to 13.7) | - | - | ||

| Far-North | 3 | 15 859 | 2834 | 15.8 (13.1 to 18.6) | 82.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Littoral | 6 | 9085 | 628 | 6.7 (4.0 to 10.1) | 96.3 | <0.001 | ||

| North | 1 | 1276 | 259 | 20.3 (18.2 to 22.6) | - | - | ||

| North-West | 2 | 561 | 39 | 6.9 (5.0 to 9.2) | 99.3 | <0.001 | ||

| South | 1 | 101 | 19 | 18.8 (12.4 to 27.5) | - | - | ||

| South-West | 5 | 7534 | 502 | 8.0 (5.5 to 10.8) | 92.8 | <0.001 | ||

| West | 1 | 982 | 41 | 4.2 (3.1 to 5.6) | - | - | ||

| Settings | ||||||||

| Overall | 22 | 86 439 | 12 353 | 10.0 (8.6 to 11.6) | 97.4 | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| Rural | 7 | 17 799 | 3159 | 13.3 (10.6 to 16.2) | 91.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Urban | 15 | 68 640 | 9194 | 9.0 (7.3 to 10.7) | 97.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Overall | 21 | 44 951 | 5669 | 9.3 (7.1 to 11.8) | 98.8 | <0.001 | 0.113 | 0.168 |

| Female | 15 | 26 614 | 224 | 8.5 (5.2 to 12.6) | 85.9 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 6 | 18 337 | 389 | 11.6 (10.1 to 13.1) | 98.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Sites | ||||||||

| Overall | 27 | 1 00 501 | 13 185 | 9.5 (7.9 to 11.3) | 98.6 | <0.001 | 0.017 | 0.954 |

| Hospital-based | 23 | 93 867 | 12 430 | 9.5 (7.7 to 11.5) | 98.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Population-based | 4 | 6634 | 755 | 9.7 (5.6 to 14.7) | 96.5 | <0.001 | ||

| Timing of data collection | ||||||||

| Overall | 27 | 1 00 501 | 13 185 | 9.5 (7.9 to 11.4) | 98.6 | <0.001 | 0.014 | 0.110 |

| Retrospective | 5 | 17 189 | 2079 | 11.4 (10.3 to 12.5) | 73.1 | 0.010 | ||

| Prospective | 22 | 83 312 | 11 106 | 9.3 (7.2 to 11.6) | 98.9 | <0.001 | ||

| Risk of bias | ||||||||

| Overall | 27 | 1 00 501 | 13 185 | 9.5 (7.9 to 11.4) | 98.6 | <0.001 | 0.017 | 0.435 |

| High | 4 | 17 279 | 2847 | 8.2 (2.3 to 17.2) | 99.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Moderate | 11 | 58 822 | 7380 | 9.0 (5.9 to 12.7) | 99.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 12 | 24 637 | 2958 | 11.0 (10.2 to 11.9) | 69.6 | <0.001 | ||

| Status regarding implementation of the HBV universal immunisation | ||||||||

| Overall | 18 | 28 761 | 3156 | 8.4 (6.8 to 10.1) | 95.5 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Before | 17 | 27 998 | 3151 | 9.2 (7.9 to 10.5) | 91.4 | <0.001 | ||

| After | 1 | 765 | 5 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.5) | - | - | ||

| HBV screening tools | ||||||||

| Overall | 21 | 47 396 | 5700 | 9.3 (7.0 to 12.0) | 98.7 | <0.001 | 0.193 | 0.239 |

| Enzyme immunoassay | 3 | 2023 | 98 | 4.2 (0.4 to 11.2) | 97.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Enzyme-linked immunoassay | 4 | 2580 | 261 | 10.0 (8.4 to 11.8) | 51.3 | 0.10 | ||

| Rapid diagnostic test | 14 | 42 793 | 5341 | 10.5 (7.5 to 13.8) | 99.0 | <0.001 |

Discussion

We investigated the prevalence of HBV infection in different populations in Cameroon. The information provided by this systematic review and meta-analysis may contribute to improve knowledge on HBV infection epidemiology in Cameroon and in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as inform national policy makers. It is important to note that only a third of the 44 studies included in this review had low risk of bias in their methodological quality. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution due to the presence of studies with poor methodological quality. However, as shown in the subgroup analysis, methodological quality did not influence HBV seroprevalence.

We found a pooled prevalence of 11.2% (95% CI 9.7% to 12.8%) close to that found in the sensitive analysis excluding high-risk participants, 10.6% (95% CI 8.6% to 12.6%). According to WHO, these prevalence rates are high (≥8%).3 This sensitive prevalence is slightly lower than the prevalence found in a global systematic review (12.2%; 95% CI 11.7% to 12.8%) published in 2013 which included 17 studies from pregnant women, blood donors, healthcare workers and general populations from Cameroon and is higher than the reported prevalence in Africa (8.8%).9 Our meta-analysis, in addition included 31 studies from 2013 to 2016. Despite the high heterogeneity between studies, there was difference between population groups for prevalence of HBV infection when excluding high-risk individuals. This sensitive analysis suggests that prevalence was homogeneous across groups: around 10% (7.1% to 10.5%) and therefore when implementing preventive strategies focusing on the reduction of this prevalence, all groups should benefit from close strategies. The prevalence reported in this study suggests that in a population of 22.25 million inhabitants like in Cameroon,12 there are about 2 250 000 inhabitants infected by HBV. Therefore, access to screening for HBV and treatment should urgently be scaled up nationwide.

Analyses suggest that the prevalence is not influenced by sex distribution, methodological quality of studies, timing of data collection, HBV screening tools and study site. Surprisingly, the prevalence of HBV infection is higher in rural areas compared with urban areas. This discrepancy should be investigated in future studies. Analyses also suggest differences across regions in Cameroon for HBV seroprevalence. We can categorise prevalence across regions in three groups: regions with high (>15%; Far-North, North and South regions), with medium (8%–15%; Centre, East and South-West) and low HBV seroprevalence (<8%, Littoral, North-West and West). Nevertheless, this result requires a cautious interpretation since certain regions in the analysis included only one study (West, North and East). Specific strategies should be implemented for rural settings and certain regions (East, Far North and South) with high prevalence. One can note that the Adamawa Region was not represented. Data also suggest that the implementation of HBV universal immunisation had good impact of HBV prevalence. This result should be interpreted with caution, only one study represented the people in which samples were collected after this implementation; and lacking data on the main HBV transmission route in the country is questionable for the interpretation. Studies are needed to estimate the main route of HBV transmission.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that focuses on HBV infection in Cameroon. We included more studies compared with previously published meta-analysis;9 in addition, the prevalence for specific populations was estimated; and the difference between sex, geographical regions, HBV screening tools, status regarding implementation of HBV universal immunisation programme and residence areas were assessed. Strong and reliable methodological and statistical procedures were used. Nevertheless, only a large representative national epidemiological study conducted at the same time in all regions and all specific groups can give a more reliable and accurate overall prevalence of HBV infection. This was done in one study but limited to young men (18–23 years).57 In addition, the review included only one study specific to children. Across studies, HBV screening tools and their sensitivity and specificity may be different; this may influence estimates.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that only a third of the studies presented low risk of bias in their methodology, the prevalence of HBV infection in Cameroon is high, both, in the general population and in specific subpopulations. These findings indicate the need of comprehensive and effective strategies to interrupt the transmission of HBV infection in the Cameroonian population. Specific attention is needed for rural settings and certain regions of the country. Health policies makers and stakeholders should facilitate access to HBV immunisation to people born before 2005.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: JJB; Search strategy: JJB. Study selection: JJB, JJN. Data extraction: JJB, ETN-M, MAA, JJN. Data analysis: JJB. Manuscript drafting: JJB, SLA. Manuscript revision: JJB, SLA, AMK, SRNN, ETN-M, MAA, JJN; Guarantor of the review: JJB. Approved the final version of the manuscript: All authors.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Prévention et lutte contre l'hépatite virale: cadre pour l'action mondiale. 2012. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/GHP_Framework_Fr.pdf

- 2. World Health Organization. Hepatitis B: Fact sheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/index.html

- 3. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/154590/1/9789241549059_eng.pdf [PubMed]

- 4. WHO Executive Board. Viral hepatitis. 2009. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB126/B126_15-en.pdf

- 5. World Health Organization. Hepatitis B: fact Sheet. 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/

- 6. Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, et al. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol 2006;45:529–38. 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El Khoury AC, Wallace C, Klimack WK, et al. Economic burden of hepatitis C-associated diseases: Europe, Asia Pacific, and the Americas. J Med Econ 2012;15:887–96. 10.3111/13696998.2012.681332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Health topics: hepatitis. 2016. http://www.who.int/topics/hepatitis/en/

- 9. Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, et al. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015;386:1546–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Reviews and Dissemination. CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare: Centers for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cameroon's National Institue of Statistics. Generalities on Cameroon. secondary generalities on Cameroon, 2016. http://www.statistics-cameroon.org/manager.php?id=11

- 13. Ducancelle A, Abgueguen P, Birguel J, et al. High endemicity and low molecular diversity of hepatitis B virus infections in pregnant women in a rural district of North Cameroon. PLoS One 2013;8:e80346 10.1371/journal.pone.0080346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Fujiwara K, et al. A new subtype (subgenotype) Ac (A3) of hepatitis B virus and recombination between genotypes A and E in Cameroon. J Gen Virol 2005;86:2047–56. 10.1099/vir.0.80922-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kramvis A, Kew MC. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Africa, its genotypes and clinical associations of genotypes. Hepatol Res 2007;37:S9–S19. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2014. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 17. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:974–8. 10.1136/jech-2013-203104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics 1954;10:101–29. 10.2307/3001666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication Bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ankouane Andoulo F, Kowo M, Talla P, et al. Epidemiology of Hepatitis B-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Cameroon. Health Sci Dis 2013;14:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Njouom R, Pasquier C, Ayouba A, et al. Low risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus in Yaounde, Cameroon: the ANRS 1262 study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;73:460–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mbougua JB, Laurent C, Kouanfack C, et al. Hepatotoxicity and effectiveness of a Nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with or without viral hepatitis B or C infection in Cameroon. BMC Public Health 2010;10:105 10.1186/1471-2458-10-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gaynes BN, Pence BW, Atashili J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of Major depression in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Bamenda, a semi-urban center in Cameroon. PLoS One 2012;7:e41699 10.1371/journal.pone.0041699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luma HN, Eloumou SA, Malongue A, et al. Characteristics of anti-hepatitis C virus antibody-positive patients in a hospital setting in Douala, Cameroon. Int J Infect Dis 2016;45:53–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tufon KA, Meriki HD, Anong DN, et al. Genetic diversity, viraemic and aminotransferases levels in chronic infected hepatitis B patients from Cameroon. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:117 10.1186/s13104-016-1916-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Birguel J, Ndong JG, Akhavan S, et al. [Viral markers of hepatitis B, C and D and HB vaccination status of a health care team in a rural district of Cameroon]. Med Trop 2011;71:201–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Forbi JC, Ben-Ayed Y, Xia GL, et al. Disparate distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes in four sub-Saharan african countries. J Clin Virol 2013;58:59–66. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.06.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abongwa LE, Clara AM, Edouard NA, et al. Sero-Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis B virus (HBV) Co-Infection among pregnant women residing in Bamenda Health District, Cameroon. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 2015;4:473–83. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abongwa LE, Kenneth P. Assessing prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B surface antigen amongst pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. European Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2016;4:32–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ankouane F, Noah Noah D, Atangana MM, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses, HIV-1/2 and syphilis among blood donors in the Yaoundé Central Hospital in the centre region of Cameroon. Transfus Clin Biol 2016;23:72–7. 10.1016/j.tracli.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frambo AA, Atashili J, Fon PN, et al. Prevalence of HBsAg and knowledge about hepatitis B in pregnancy in the Buea Health District, Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:394 10.1186/1756-0500-7-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dionne-Odom J, Mbah R, Rembert NJ, et al. Hepatitis B, HIV, and Syphilis Seroprevalence in Pregnant Women and Blood Donors in Cameroon. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016;2016:1–8. 10.1155/2016/4359401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eboumbou Moukoko CE, Ngo Sack F, Essangui Same EG, et al. HIV, HBV, HCV and T. pallidum infections among blood donors and Transfusion-related complications among recipients at the Laquintinie hospital in Douala, Cameroon. BMC Hematol 2014;14:5 10.1186/2052-1839-14-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Enow Tanjong R, Teyim P, Kamga HL, et al. Sero-prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis viruses and their correlation with CD4 T-cell lymphocyte counts in pregnant women in the Buea Health District of Cameroon. IJBCS 2016;10:219–31. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Feldt T, Sarfo FS, Zoufaly A, et al. Hepatitis E virus infections in HIV-infected patients in Ghana and Cameroon. J Clin Virol 2013;58:18–23. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fomulu NJ, Morfaw FL, Torimiro JN, et al. Prevalence, correlates and pattern of Hepatitis B among antenatal clinic attenders in Yaounde-Cameroon: is perinatal transmission of HBV neglected in Cameroon? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:158 10.1186/1471-2393-13-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fouelifack Ymele F, Keugoung B, Fouedjio JH, et al. High rates of Hepatitis B and C and HIV infections among blood donors in Cameroon: a Proposed Blood Screening Algorithm for Blood Donors in Resource-Limited Settings. J Blood Transfus 2012;2012:1–7. 10.1155/2012/458372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Foupouapouognigni Y, Mba SA, Betsem à Betsem E, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infections in the three Pygmy groups in Cameroon. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:737–40. 10.1128/JCM.01475-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fritzsche C, Becker F, Hemmer CJ, et al. Hepatitis B and C: neglected diseases among health care workers in Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2013;107:158–64. 10.1093/trstmh/trs087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halle MP, Luma NH, Temfack E, et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis B surface antigen and AntiHIV antibodies among patients on Maintenance Haemodialysis in Douala - Cameroon. Health Diseases and Sciences 2013;14:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kfutwah AK, Tejiokem MC, Njouom R. A low proportion of HBeAg among HBsAg-positive pregnant women with known HIV status could suggest low perinatal transmission of HBV in Cameroon. Virol J 2012;9:62 10.1186/1743-422X-9-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mogtomo ML, Fomekong SL, Kuate HF, et al. [Screening of infectious microorganisms in blood banks in Douala (1995-2004)]. Sante 2009;19:3–8. 10.1684/san.2009.0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kouanfack C, Aghokeng AF, Mondain AM, et al. Lamivudine-resistant HBV infection in HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a public routine clinic in Cameroon. Antivir Ther 2012;17:321–6. 10.3851/IMP1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Laurent C, Bourgeois A, Mpoudi-Ngolé E, et al. High rates of active hepatitis B and C co-infections in HIV-1 infected cameroonian adults initiating antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2010;11:85–9. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Loriette M, Birguel J, Damza R, et al. [An experience of hepatitis B control in a rural area in Far North Cameroon]. Med Sante Trop 2015;25:422–7. 10.1684/mst.2015.0507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mbanya DN, Takam D, Ndumbe PM. Serological findings amongst first-time blood donors in Yaoundé, Cameroon: is safe donation a reality or a myth? Transfus Med 2003;13:267–73. 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2003.00453.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mbanya D, Binam F, Kaptue L. Transfusion outcome in a resource-limited setting of Cameroon: a five-year evaluation. Int J Infect Dis 2001;5:70–3. 10.1016/S1201-9712(01)90028-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mbopi-Keou FX, Nkala IV, Kalla GC, et al. [Prevalence and factors associated with HIV and viral hepatitis B and C in the city of Bafoussam in Cameroon]. Pan Afr Med J 2015;20:156 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.156.4571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mondinde Ikomey G, Jacobs GB, Tanjong B, et al. Evidence of Co and triple infections of Hepatitis B and C amongst HIV infected pregnant women in Buea, Cameroon. Health Sci Dis 2016;17. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sack FN, Noah Noah D, Zouhaïratou H, et al. [Prevalence of HBsAg and anti-HCV antibodies in homozygous sickle cell patients at Yaounde Central Hospital]. Pan Afr Med J 2013;14:40 10.11604/pamj.2013.14.40.2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Noah DN, Ngaba GP, Bagnaka SF, et al. [Evaluation of vaccination status against hepatitis B and HBsAg carriage among medical and paramedical staff of the Yaoundé Central Hospital, Cameroon]. Pan Afr Med J 2013;16:111 10.11604/pamj.2013.16.111.2760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Noah DN, Nko'ayissi G, Ankouane FA, et al. Présentation clinique, biologique et facteurs de Risque Du Carcinome hépatocellulaire: une étude Cas-Témoins à Yaoundé Au Cameroun. Revue de Médecine et de Pharmacie 2014;4. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Noah Noah D, Njouom R, Bonny Aim?, et al. HBs antigene prevalence in blood donors and the risk of transfusion of hepatitis b at the central hospital of Yaounde, Cameroon. Open Journal of Gastroenterology 2011;01:23–7. 10.4236/ojgas.2011.12004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Noah DN, Andoulo FA, Essoh BVM, et al. Prevalence of HBs antigen, and HCV and HIV antibodies in a young male Population in Cameroon. Open Journal of Gastroenterology 2015;05:185–90. 10.4236/ojgas.2015.512028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Ndoula ST, et al. Prevalence, infectivity and correlates of hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in a rural district of the Far North Region of Cameroon. BMC Public Health 2015;15:454 10.1186/s12889-015-1806-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Noubiap JJ, Joko WY, Nansseu JR, et al. Sero-epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis infections among first-time blood donors in Edéa, Cameroon. Int J Infect Dis 2013;17:e832–e837. 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Noubiap JJ, Aka PV, Nanfack AJ, et al. Hepatitis B and C Co-Infections in some HIV-Positive populations in Cameroon, West Central Africa: analysis of Samples Collected over more than a decade. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137375 10.1371/journal.pone.0137375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ottop FM, Atashili J, Ndumbe PM. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on glycemia and transaminase levels in patients living with HIV/AIDS in Limbe, Cameroon. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2013;12:23–7. 10.1177/1545109712447199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tatsilong HO, Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, et al. Hepatitis B infection awareness, vaccine perceptions and uptake, and serological profile of a group of health care workers in Yaoundé, Cameroon. BMC Public Health 2016;15:706 10.1186/s12889-016-3388-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rey-Cuille MA, Njouom R, Bekondi C, et al. Hepatitis B virus exposure during childhood in Cameroon, Central African Republic and Senegal after the integration of HBV vaccine in the expanded program on immunization. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013;32:1110–5. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829be401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Salpini R, Fokam J, Ceccarelli L, et al. High burden of HBV-Infection and atypical HBV strains among HIV-infected Cameroonians. Curr HIV Res 2016;14:165–71. 10.2174/1570162X13666150930114742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shevell L, Meriki HD, Cho-Ngwa F, et al. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-1 and hepatitis B virus co-infection and risk factors for acquiring these infections in the Fako division of Southwest Cameroon. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1066 10.1186/s12889-015-2386-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tagny CT, Diarra A, Yahaya R, et al. Characteristics of blood donors and donated blood in sub-Saharan Francophone Africa. Transfusion 2009;49:1592–9. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zoufaly A, Onyoh EF, Tih PM, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis B and syphilis co-infections among HIV patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in the north-west region of Cameroon. Int J STD AIDS 2012;23:435–8. 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zoufaly A, Fillekes Q, Hammerl R, et al. Prevalence and determinants of virological failure in HIV-infected children on antiretroviral therapy in rural Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Antivir Ther 2013;18:681–90. 10.3851/IMP2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015298supp001.pdf (192.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015298supp002.pdf (233.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015298supp003.pdf (271.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015298supp004.pdf (5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015298supp005.pdf (4.5KB, pdf)