Abstract

Introduction

Despite the widespread acceptance of conventional treatment using composite resin in primary teeth, there is limited evidence that this approach is the best option in paediatric clinics. Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) using high-viscosity glass ionomer cement has gradually become more popular because it performs well in clinical studies, is easy to handle and is patient friendly. Therefore, the aim of this randomised clinical trial study is to compare the restoration longevity of conventional treatment using composite resin with that of ART in posterior primary teeth. As secondary outcomes, cost-efficacy and patient self-reported discomfort will also be tested.

Methods and analysis

Children aged 3–6 years presenting with at least one occlusal and/or occlusal-proximal cavity will be randomly assigned to one of two groups according to the dental treatment: ART (experimental group) or composite resin restoration (control group). The dental treatment will be performed at a dental care trailer located in an educational complex in Barueri/SP, Brazil. The unit of randomisation will be the child. A sample size of 240 teeth with occlusal cavities and 188 teeth with occlusal-proximal cavities has been calculated. The primary outcome will be restoration longevity, which will be clinically assessed after 6, 12, 18 and 24 months by two examiners. The duration of the dental treatment and the cost of all materials used will be considered when estimating the cost-efficacy of each treatment. Individual discomfort will be measured after each dental procedure using the Facial Scale of Wong-Baker.

Ethics and dissemination

This clinical trial was approved by the local ethics committee from the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of São Paulo (registration no. 1.556.018). Participants will be included after their legal guardians have signed an informed consent form containing detailed information about the research.

Trial registration number

www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02562456; Pre-results.

Keywords: health economics, oral medicine, paediatrics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Considering that the success of a restorative treatment is intrinsically related to the handling of the material, it seems necessary to study these techniques under controlled conditions to extract from them the best clinical performance they can offer.

An efficacy study can maximise the likelihood of observing an intervention effect by investigating the benefits and harms of it under highly controlled conditions.

This is the first clinical trial comparing the longevity, cost-efficacy and self-reported discomfort assessment between conventional restoration using composite resin and ART with high-viscosity glass ionomer cement in posterior primary teeth.

Blinding of operators and patients will not be possible because of the evident differences between the techniques.

Introduction

Restorative care in primary teeth is part of the comprehensive oral health treatment of children and adolescents,1 which should guarantee appropriate functional and aesthetic conditions until tooth exfoliation.2 There is an ongoing search for ideal restorative materials for use in paediatric dentistry,1 but a lack of evidence persists.3–5

Conventional treatment using composite resin is still one of the most common approaches used in paediatric dental clinics.6 Despite the aesthetic quality, preservation of dental structure and abrasion wear rate similar to that of natural primary teeth,6 all composite resins suffer polymerisation shrinkage, which can jeopardise marginal integrity2 and restoration longevity. In addition, to take full advantage of the properties of composite resin, absolute isolation with rubber dam is necessary,7 making the restoration technique sensitive and time consuming2 and more traumatic for the paediatric patient.8

An alternative to the use of composite resin is atraumatic restorative treatment (ART), a minimal intervention approach that simplifies the restorative procedure through the exclusive use of hand instruments, followed by the application of a chemical-adhesive material.9 ART is reported to provoke less anxiety and less pain and rarely requires local anaesthesia.10 Currently, the material of choice for ART is high-viscosity glass ionomer cement (GIC),11 which provides biocompatibility, fluoride release, chemical adhesion to the tooth surface12 and a coefficient of thermal expansion similar to that of natural teeth.4 Moreover, it is easy to use because it can be placed in a single increment.2

The international scientific literature has already designated ART as an appropriate procedure to treat occlusal and occlusal-proximal cavities in primary teeth when compared with amalgam.4 5 However, few clinical studies have compared composite resin performance in primary teeth with any other dental material.13–15 Moreover, patient-based parameters must also be assessed to enable a more effective and appropriate choice of treatment for each individual. In this context, few reports have been found in the literature regarding those outcomes such as patient’s acceptability16 17 16 17 and cost of restorative treatments18 19

Because of the need to establish the best scientific evidence about restorative treatment in primary teeth, this study aims to compare the efficacy of two types of treatment in primary molars (ART using high-viscosity GIC and composite resin restoration) using a superiority randomised clinical trial with parallel arms.

Our hypothesis is that the longevity of restorations using the conventional treatment with resin composite under rubber dam for occlusal and occlusal-proximal cavities in primary molars differs from the longevity of atraumatic restorations using high-viscosity glass ionomer. Regarding the secondary outcomes, we expect that ART has a better cost-efficacy, and it is the only treatment highly accepted among children in this study.

Methods/design

The present protocol follows the guidelines of the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) as detailed in online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjopen-2016-015542supp001.pdf (106.1KB, pdf)

This clinical trial was recorded in the database for registration of clinical studies (Clinicaltrials.gov registration NCT02562456). This study is part of a partnership with the city of Barueri, São Paulo, and it is nested to the Caries Detection in Children-2 study (registration NCT02473107). Each participant will be encoded by a number to guarantee information confidentiality. Any files containing identifiable data will be stored in locked filing cabinets, and only researchers will have access to participants’ information.

The final trial dataset will be available for inspection with the coordinator’s endorsement. Results will be fully reported in peer-reviewed journals, the patients’ newsletter and on the website. If participants develop any dental treatment needs after completion of the trial, they will be referred to the health service of the city of Barueri, São Paulo.

Sample description

Participants will be selected after screening in a dental care trailer located in the Professor Carlos Osmarinho de Lima Educational Complex (Barueri/SP). All healthy children who live in the city of Barueri seeking dental treatment are potential participants in our project. The trailer is set up as a regular dental office. The inclusion criteria are (1) children aged 3–6 years; (2) whose parents consent their participation in the research; (3) with at least one occlusal and/or occlusal-proximal cavity in a primary molar; (4) the carious lesion should be in dentin, clinically classified as a shallow or a medium cavity; (5) the tooth of interest should not be associated with a fistula, abscess, pulp exposure, history of spontaneous dental pain or mobility and (6) the cavity of interest should allow the access by the operator using hand instruments (International Caries Detection and Assessment System 5 or 6). Children who present behaviour problems during the clinical examination or during dental treatment will be excluded from our study.

The child will be set as the unit of randomisation, which means that all eligible teeth of a child included in our research will be treated according to the same treatment independently of the number of cavities. For sample size calculation, data on the longevity of 2 years of occlusal and occlusal-proximal composite resin restorations15 were extracted from the literature as 86% and 60%, respectively. A minimum difference of 10% between treatment longevities was set as the superiority limit. Taking the significance level as 5%, a power of 80% and the addition of 40% owing to study design (cluster per children), the minimum number of teeth per group was calculated using a two-tailed test. In addition, a sample loss of 20% was estimated, resulting in 204 teeth for the occlusal group and 240 teeth for the occlusal-proximal group (table 1).

Table 1.

Sample distribution

| Groups | Type of cavity | |

| Occlusal | Occlusal-proximal | |

| Control (composite resin) | 102 | 120 |

| Experimental (ART) | 102 | 120 |

| Total | 204 | 240 |

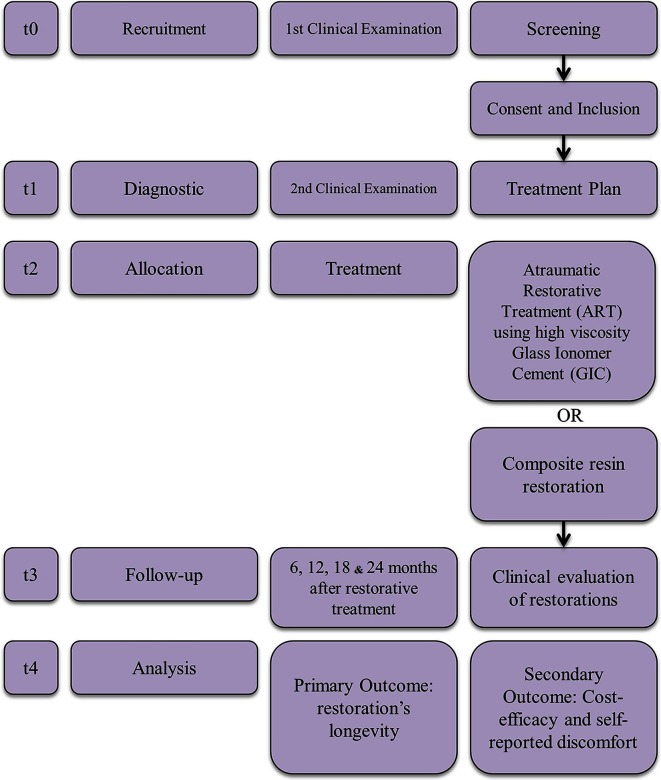

Recruitment will take place from December 2015 to June 2017. Each participant will be enrolled in the study for about 25 months: 1 month for the randomised clinical trial (RCT) diagnosis and treatment, followed by a 24-month observation period. Details are illustrated in figure 1. Participants’ enrolment will be facilitated by locating the trailer inside an educational complex.

Figure 1.

Clinical trial's timeline.

After screening, participants who have met the eligibility criteria will have their registration data collected and will be clinically examined by one operator. Radiographical examination will be performed if any doubts about the pulp involvement of the tooth of interest persist. As the child will receive complete dental treatment during the study, radiographical examination will also be used if any other treatment need demand it.

The same operator will also determine the dental caries experience of the child which will be assessed based on the WHO criteria that only considers evident carious cavities and restored and/or missing teeth as a result of carious progression.20 Thus, the following indices will be calculated for each child: decayed, indicated for extraction or filled teeth (primary) (deft) and decayed, missed and filled teeth (permanent) (DMFT); children in whom (deft)+(DMFT) is ≤3 will be classified as having low dental caries experience. Children with higher scores will be classified as having high dental caries experience.21

The randomization process will be designed in blocks of different sizes generated by software. Opaque, sealed and sequentially numbered envelopes will be used to randomise the participants into the treatment groups.

The restorative treatment will be performed by four trained and calibrated operators who will disclose which treatment they are performing at the commencement of the restorative procedure. However, blinding participants and operators will not be possible due to the evident differences between both techniques.

Study groups

Participants will be randomly assigned into two different groups:

Group I (control): composite resin restoration, using 37% phosphoric acid, Adper Scotchbond Multipurpose adhesive system (3M/ESPE) and Filtek Z350 resin-composite (3M/ESPE).

Group I (ART): Selective caries removal with hand instruments and restoration performed with high viscous glass ionomer cement (Fuji IX, GC Corp).

Treatment protocol

Composite resin restoration

All children from group I will be treated according to conventional techniques using composite resin:

Use local anaesthesia;

Maintain absolute isolation of the operatory field with rubber dam and clamp;

Selective Caries removal:

use hand excavators to remove caries in dentin. Both infected and affected dentin should be removed from the dentin–enamel junction, maintaining the affected dentin in the remaining dental walls. If necessary, round bur at high speed under water cooling will be used to remove the unsupported enamel;

Etch enamel for 15 s and dentin for 7 s using 37% phosphoric acid, followed by rinsing for the same amount of time and drying with compressed air;

Apply the Adper Scotchbond Multipurpose adhesive system (3M/ESPE) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines: primer application followed by gentle drying for 5 s; then polymerisation of the adhesive for 10 s with the XL 3000 curing light (3M/ESPE);

Apply light-cured Filtek Z350 resin (3M/ESPE) using the oblique incremental placement technique. Each increment should be polymerised for 20 s. In occlusal-proximal cavities, an adapted matrix strip should be used with a wooden wedge to maintain it in place, providing appropriate contour to the restoration;

Remove the rubber dam and check the occlusion with articulating paper. If necessary, finishing burs (F and FF) should be used under a cooling spray.

ART using GIC

All children from group II will be treated according to the ART philosophy as described by Frencken et al 22:

Maintain relative isolation of the operatory field with cotton rolls;

Remove caries: using only hand excavators compatible with the size of the carious cavity. Both infected and affected dentin should be removed from the dentin–enamel junction. Thus, as described for group I, the affected dentin will be maintained in the remaining walls;

Clean the cavity: cavity walls should be cleaned with cotton balls moistened with water;

Condition the dentin: apply a drop of 11.5% polyacrylic acid on a cotton ball for 15 s. Then, wash the cavity with three cotton balls moistened with water and dry using three more cotton balls;

Use correct dosage (one spoon measure of the powder to one drop of polyacrylic acid): place the polyacrylic acid flask vertically and upside down, wait a few seconds until the bubbles rise and then drip two drops. Use the first drop to condition the cavity because this initial drop may contain bubbles;

Hand mix: spread the second drop of polyacrylic acid over the paper pad. Then, mix the powder in with the acid in two stages—manipulate the first part for 10 s and the second part for 15–20 s, applying moderate pressure. Use the material only while it remains glossy;

Apply GIC: insert the GIC with a #1 spatula followed by finger pressure using petroleum jelly for a few seconds. For occlusal-proximal cavities, use an adapted matrix strip with a wooden wedge to maintain it in place, providing appropriate contour to the restoration. Protecting the restoration with petroleum jelly is necessary to inhibit syneresis and imbibition;

Check the occlusion: after the initial set (approximately 5 min), check the occlusion with articulating paper. If necessary, sharp hand instruments should be used for adjustments. A new layer of petroleum jelly should be applied to the surface of the restoration;

Instruct the patient not to eat solid food for 1 hour.

Dental care other than restorative treatment related to this project will also be provided in the dental care trailer by three operators trained in the same philosophy regarding non-cavitated carious lesions23 and pulp treatment.24 Moreover, all participants and their respective legal guardians will receive verbal instructions about the use of toothpaste with a minimum concentration of 1000 ppm fluoride to prevent dental caries.25

The risks related to the present research are similar to those found during conventional clinical dental treatment. Thus, there is no data monitoring committee. Independent surveillance of trial data collection, management and analysis will be undertaken by the principal investigator who has overall responsibility for the study and is in charge of the data.

Outcomes

The primary outcome will be the longevity of both restorative treatments after follow-up for 2 years. Secondary outcomes will include the cost-efficacy of both types of restorative treatment and self-reported discomfort.

Longevity

Treatment longevity will be evaluated after 6, 12, 18 and 24 months by two trained examiners. The intraexaminer and interexaminer concordances will be calculated using Cohen’s kappa test. Only scores above 0.7 will be accepted. After prophylaxis, the occlusal restorations will be clinically evaluated according to the Frencken and Holmgren26 criteria (online supplementary appendix 2).

For occlusal-proximal restorations, the adopted criteria are those proposed by Roeleveld et al.27 (online supplementary appendix 3). The width and depth of marginal defects, the surface wear and the excess or lack of material will be measured using the WHO CPI periodontal probe, which has a ball-shaped tip 0.5 mm in diameter.

If any treatment need is noted at the return visits, the procedure will be performed by one of the three trained operators until the case is resolved. Oral hygiene and fluoride use instructions will be repeated at each return visit for all children.

Data from each participant will be registered in clinical records for future statistical analysis. Data quality will be ensured by validation checks that include missing data, out of range values and illogical and invalid responses. All data entered will be audited by the coordinator, and data queries will be raised as necessary.

Cost-efficacy

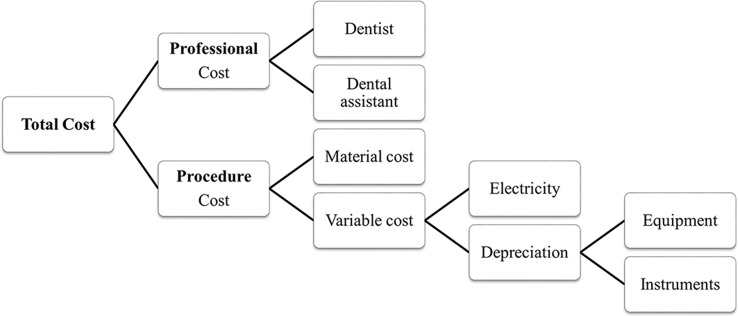

The direct cost analysis will be based on previous publications28 29 adjusted to the Brazilian reality.30 Both the professional cost and the procedure cost will be considered (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram of total cost calculation.

To calculate the professional cost, we will use the previous calculation of Floriano et al,30 such that the time spent in each session will be converted to hours and multiplied by the average income of a dentist per hour ($13.89) and a dental assistant per hour ($7.06) as ruled by the Brazilian federal law No 3999/61.30 31 To estimate the procedure cost, we will consider both the variable cost, which includes electricity and the depreciation of instruments and equipment, and the materials cost.28 32 To calculate the instruments and equipment depreciation (peripherals and dental chair), we will use the previous calculations of da Mata et al 18 and Oscarson et al 29 that considers their cost, a lifespan of 3 years for instruments18 and 5 years for equipment30 and a monthly use of 160 hours.

A researcher other than the operator will time each restorative treatment session, including the return visits, and will register in predetermined sheets the specifications and quantity of all materials used. Prices will be inferred from the market value converted to US dollars and obtained by averaging the values from different places that have commercialised the products used. The prices will also be updated during the course of the study.

In order to estimate the cost-efficacy, the incremental cost-efficacy ratio (ICER) will be estimated by dividing the average total cost by the survival after 2 years of each treatment:

ICER = (costART−efficacyART) / (costCT−efficacyCT)

Child self-reported discomfort

The self-reported discomfort of each child will be evaluated using the Wong-Baker Facial Scale.33 This scale indicates the discomfort of an individual who has to choose among six faces, each one expressing different facial expressions. The first image is a smiling happy face, followed by gradually less cheerful expressions up to the last one, which is a very sad face covered in tears. The scale will be applied immediately after each restorative treatment session by the operator who is timing the procedure.

The participant will be asked to choose the face that best match how he or she felt during the treatment. This answer should be given solely by the child, with no parental or professional interference.34

Data analysis

To compare the longevity of the restorations, both Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox regression with shared frailty will be applied. The association between restoration longevity and caries experience or the type of cavity will also be evaluated using Cox regression with shared frailty. To determine the data normality, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test will be used. In relation to the secondary outcomes, the comparison between groups in relation to the time spent in each procedure as well as the average cost of a restoration will be done through the use of linear regression adjusted to the cluster effect. Multilevel Poisson regression will be used to compare both groups and the other independent variables to the self-reported discomfort. The significance level will be adjusted to 5%.

Ethics and dissemination

This clinical trial was approved by the ethics committee of research in humans from the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Sao Paulo (registration #1.556.018). Participants will be included after their parents or legal guardians have signed an informed consent form containing detailed information about the research. This study will involve the publication of grouped data collected from participants’ individual information. This statement will be described in the consent form of each participant.

bmjopen-2016-015542supp002.pdf (36.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015542supp003.pdf (35.8KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo—FAPESP (grants #2015/11356–6 and #2012/50716–0) for funding this trial, and all undergraduate and postgraduate students involved in the dental care trailer project. Finally, we acknowledge all participants in the postgraduate Paediatric Dentistry Seminar of FOUSP (Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade de São Paulo) for the constructive criticism they provided.

Footnotes

Contributors: DPR, MMB, FMM and IF contributed to the conception of this trial. DPR was responsible for its design. DPR is the trial coordinator, and NML is the principal investigator. DPR, NML and IO drafted the protocol. IF is in charge of the recruitment of participants. NML is responsible for the patients’ treatment. CSS and LY are responsible for timekeeping, recording materials and organising treatment. TKT is responsible for patient evaluations over time. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Local Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Not applicable yet. Any data have been collected.

References

- 1. Dhar V, Hsu KL, Coll JA, et al. Evidence-based update of pediatric dental restorative procedures: dental materials. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2015;39:303–10. 10.17796/1053-4628-39.4.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Casagrande L, Dalpian DM, Ardenghi TM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of adhesive restorations in primary molars. 18-month results. Am J Dent 2013;26:351–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yengopal V, Harneker SY, Patel N, et al. Dental fillings for the treatment of caries in the primary dentition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD004483 10.1002/14651858.CD004483.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mickenautsch S, Yengopal V, Banerjee A. Atraumatic restorative treatment versus amalgam restoration longevity: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig 2010;14:233–40. 10.1007/s00784-009-0335-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raggio DP, Hesse D, Lenzi TL, et al. Is atraumatic restorative treatment an option for restoring occlusoproximal caries lesions in primary teeth? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent 2013;23:435–43. 10.1111/ipd.12013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qvist V, Poulsen A, Teglers PT, et al. The longevity of different restorations in primary teeth. Int J Paediatr Dent 2010;20:1–7. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.01017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heintze SD, Rousson V. Clinical effectiveness of direct class II restorations—a meta-analysis. J Adhes Dent 2012;14:407–31. 10.3290/j.jad.a28390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schriks MC, van Amerongen WE. Atraumatic perspectives of ART: psychological and physiological aspects of treatment with and without rotary instruments. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003;31:15–20. 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frencken JE, Pilot T, Songpaisan Y, et al. Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART): rationale, technique, and development. J Public Health Dent 1996;56:135–40. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frencken JE. The state-of-the-art of ART restorations. Dent Update 2014;41:218–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van 't Hof MA, Frencken JE, van Palenstein Helderman WH, et al. The atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) approach for managing dental caries: a meta-analysis. Int Dent J 2006;56:345–51. 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2006.tb00339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Dijken JW, Pallesen U. Long-term dentin retention of etch-and-rinse and self-etch adhesives and a resin-modified glass ionomer cement in non-carious cervical lesions. Dent Mater 2008;24:915–22. 10.1016/j.dental.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fuks AB, Araujo FB, Osorio LB, et al. Clinical and radiographic assessment of class II esthetic restorations in primary molars. Pediatr Dent 2000;22:479–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ersin NK, Candan U, Aykut A, et al. A clinical evaluation of resin-based composite and glass ionomer cement restorations placed in primary teeth using the ART approach: results at 24 months. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137:1529–36. 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alves dos Santos MP, Luiz RR, Maia LC. Randomised trial of resin-based restorations in class I and class II beveled preparations in primary molars: 48-month results. J Dent 2010;38:451–9. 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Novaes TF, Matos R, Raggio DP, et al. Children's discomfort in assessments using different methods for approximal caries detection. Braz Oral Res 2012;26:93–9. 10.1590/S1806-83242012000200002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Staman NM, Townsend JA, Hagan JL, et al. Observational study: discomfort following dental procedures for children. Pediatr Dent 2013;35:52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. da Mata C, Allen PF, Cronin M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ART restorations in elderly adults: a randomized clinical trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014;42:79–87. 10.1111/cdoe.12066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mickenautsch S, Munshi I, Grossman ES, et al. Comparative cost of ART and conventional treatment within a dental school clinic. SADJ 2002;57:135–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO(World Health Organization). Oral health surveys: basic methods. 3 ed Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saúde BMda. Projeto SB Brasil 2010: condições de saúde bucal da população brasileira 2009-2010. Brasília: Resultados principais, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frencken JE, Pilot T, Songpaisan Y, et al. Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART): rationale, technique, and development. J Public Health Dent 1996;56:135–40. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibson G, Jurasic MM, Wehler CJ, et al. Supplemental fluoride use for moderate and high caries risk adults: a systematic review. J Public Health Dent 2011;71:no–84. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cerqueira DF, Mello-Moura AC, Santos EM, et al. Cytotoxicity, histopathological, microbiological and clinical aspects of an endodontic iodoform-based paste used in pediatric dentistry: a review. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2008;32:105–10. 10.17796/jcpd.32.2.k1wx5571h2w85430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, et al. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 2010;20:1–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frencken JE, Holmgren CF. Tratamento restaurador atraumático (ART) para a cárie dentária. São Paulo: Santos, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roeleveld AC, van Amerongen WE, Mandari GJ. Influence of residual caries and cervical gaps on the survival rate of class II glass ionomer restorations. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2006;7:85–90. 10.1007/BF03320820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takanashi Y, Penrod JR, Lund JP, et al. A cost comparison of mandibular two-implant overdenture and conventional denture treatment. Int J Prosthodont 2004;17:199–6. 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oscarson N, Källestål C, Fjelddahl A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of different caries preventive measures in a high-risk population of Swedish adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003;31:169–78. 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Floriano I, Gimenez R, Reyes A, et al. Análise de custos de diferentes abordagens para avaliação de lesões de cárie em dentes decíduos. Brazilian Oral Research 2013;27:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morita MC, Haddad AE, Araújo ME. Perfil atual e tendências do cirurgião-dentista brasileiro. Maringá: Dental Press Internacional, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kawai Y, Murakami H, Takanashi Y, et al. Efficient resource use in simplified complete denture fabrication. J Prosthodont 2010;19:512–6. 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2010.00628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs 1988;14:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Novaes TF, Matos R, Raggio DP, et al. Influence of the discomfort reported by children on the performance of approximal caries detection methods. Caries Res 2010;44:465–71. 10.1159/000320266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015542supp001.pdf (106.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015542supp002.pdf (36.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015542supp003.pdf (35.8KB, pdf)