Abstract

Objectives

Hysterectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures performed on women in developed countries; however, little is known about the epidemiology of hysterectomy in low-income to middle-income regions. This study seeks to evaluate the prevalence of hysterectomy and its risk factors in rural China.

Methods

Questionnaires were collected from 3328 female adults aged 25–69 years in rural Anyang, China, in 2009–2011. Hysterectomy status was ascertained by the gynaecologist at the time of cytological test. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to assess the risk factors for hysterectomy.

Results

The overall prevalence of hysterectomy was 3.31% (110/3328). Women above the age of 40 years had a higher prevalence of prior hysterectomy, compared with those aged 25–39 years (5.01% vs 0.33%). Obesity was marginally related with a higher risk of hysterectomy (adjusted OR=1.59; 95% CI 0.99 to 2.56; body mass index (BMI) ≥28.0 vs 18.5 ≤ BMI <24.0). History of prior pregnancy loss conferred a greater risk for hysterectomy (adjusted OR=1.51; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.23). Of the 75 (68.18%, 75/110) cases who provided further information on hysterectomy, 84.00% (63/75) had undergone total abdominal hysterectomy and 70.67% (53/75) had received surgery for leiomyoma.

Conclusions

Rural Chinese women had a relatively low prevalence of hysterectomy, and the majority of reported hysterectomies were performed abdominally for leiomyoma. Hysterectomy prevalence differed significantly by age, BMI and history of pregnancy loss. This study expands the current understanding of the epidemiology of hysterectomy in lower resource areas.

Keywords: Gynaecology, Hysterectomy, Prevalence, Epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to demonstrate the prevalence of and factors associated with hysterectomy in a general population in rural China; one of the main strengths is, therefore, the population-based nature and low-resource setting of this study.

The use of hysterectomy status data ascertained by a gynaecologist in a cervical cytology screening programme in rural China, where no regional or national databases were available, enabled us to estimate the prevalence and risk factors of hysterectomy in this area.

The possibility of a response bias of participants may reduce the generalisability of our findings to a wider population.

The small number of hysterectomy cases may have affected the precision of our assessment of the predictors of hysterectomy.

Introduction

Hysterectomy is one of the most frequent surgical procedures performed on women in developed countries.1 The epidemiology of hysterectomy in the female general population is of public health importance because this procedure may affect the population at risk for uterine diseases,2 and it may also be associated with significant socioeconomic and personal consequences when widely performed. Previous studies, mainly undertaken in developed regions, have shown that the prevalence of hysterectomy varies substantially by race and geographical area (4%–40%).3–7 Education level, age at first birth, parity, number of miscarriages and other potential risk factors have been inconsistently associated with the risk of hysterectomy.5 8–10 The indications for and surgical techniques used for hysterectomy have also been found to differ across regions1 4 11–13; however, in general, the major indication for hysterectomy is leiomyoma, and the dominant surgical type is abdominal hysterectomy.1 14

Until now, the epidemiology of hysterectomy in low-income to middle-income countries, including China, remains largely unknown. This population-based, cross-sectional study, among 3328 rural Chinese women, seeks to (1) assess the prevalence and risk factors of hysterectomy and (2) investigate indications for and types of hysterectomy among identified cases.

Methods

Study population

This population-based survey was part of an ongoing oesophageal cancer cohort study in rural Anyang, China.14 Anyang is an agricultural region of low income with a per capita gross domestic product of US$3672 (2010). Like in other rural areas of China, the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS, a government-run voluntary insurance programme), initiated in 2003, is a major health insurance programme in rural Anyang. In 2013, the per capita premium was $57.8, and NRCMS accounted for 99% of all rural residents in China.15 The current investigation used a subset including six of the nine target villages which were cluster-sampled in the parent cohort study conducted from 2009 to 2011. Eligibility criteria for subjects enrolled in this study were as follows: (1) female permanent residency in the target villages (registered in China’s unique household registration (Hukou) system); (2) aged 25–69 years; (3) no prior diagnosis of cancer (nine residents were excluded before enrolment because of self-reported history of cancer including one with cervical cancer), mental disorder or cardiovascular disease; and (4) no history of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus or HIV infection. All participants in this study provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Peking University School of Oncology, China. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Measurements

Briefly, hysterectomy status was ascertained by a gynaecologist at the time of gynaecological examination and cytological test. Data on sociodemographic factors, cigarette smoking (defined as at least one cigarette or more per day for at least 1 year), alcohol consumption (defined as the consumption of Chinese liquor two or more times per week for at least 1 year), reproductive history and personal health habits (eg, genital washing before sexual intercourse) were collected through face-to-face interviews before gynaecological tests on the same day. Height and weight were measured by the interviewers.

For cases reporting a hysterectomy, the time of the procedure along with the information on the indications for and surgical techniques used to perform hysterectomy were also recorded. In this study, the modes of hysterectomy were divided into six categories, including total abdominal hysterectomy (involving removal of the uterus and its attached cervix through an incision in the lower abdomen), subtotal abdominal hysterectomy (involving removal of only the uterine body, leaving the cervix intact, through an incision in the lower abdomen), vaginal hysterectomy (involving removal of the uterus via the vagina, without an abdominal incision), laparoscopic hysterectomy (involving the use of laparoscopy to perform hysterectomy), radical hysterectomy (involving removal of the uterus and resection of the ventral or lateral parametria) and other unspecified hysterectomy.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates along with 95% CI were estimated using a null linear regression model implemented with the generalised estimating equation (GEE) with a robust sandwich estimator of covariance to adjust for intracluster correlation.16 The China 2010 Population Census data and the WHO world standard population data were used for calculating the adjusted prevalence of prior hysterectomy.17 Potential risk factors that were statistically significant in univariate GEE regression analyses were entered in the final multivariate GEE regression models. Significant differences between groups were quantified by calculating adjusted OR and 95% CI. Tests for linear trends were performed by treating ordered categorical variables as continuous variables in the GEE regression analyses. Linear regression models were used to determine whether any variables in the multivariate models were highly collinear. In this study, all variance inflation factors were below 3.0 and therefore within the acceptable range.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.12.0. All statistical tests were two-sided at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of 3849 eligible candidates, 3328 (86.5%) were enrolled in the study (the other 521 candidates, who were more frequently of younger age, did not participate, mainly because they were employed outside of Anyang). The median age of these 3328 participants was 43 years. Most subjects were married or cohabiting (95.00%); of the participants, 92.85% had a level of education of less than 9 years, and 88.52% were engaged in farming (see online supplementary table S1). Both cigarette smoking (0.27%) and alcohol consumption (0.21%) were uncommon. Approximately one-half of the women were overweight (31.40%) or obese (18.66%), 43.27% reported menarche at the age of ≤15 years, 39.84% had their first birth at the age of ≤22 years, 37.71% had a parity >2, 43.66% reported having a history of fetal loss, 77.34% used an intrauterine contraceptive device, 37.89% reported having had a tubal ligation, and 8.80% had a history of postintercourse bleeding.

bmjopen-2016-015351supp001.pdf (183.3KB, pdf)

Prevalence and risk factors for hysterectomy

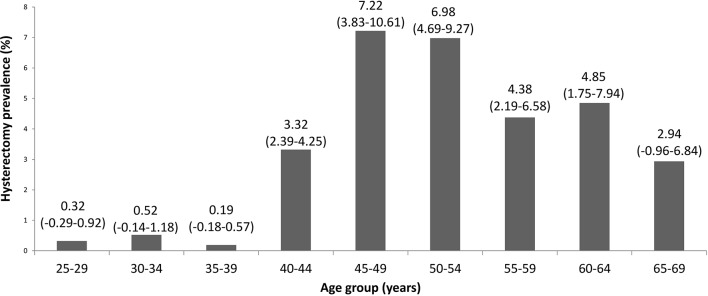

The overall prevalence of prior hysterectomy was 3.31% (110/3328, 95% CI 2.49 to 4.12). Adjusted estimates of prevalence standardised by the age structure of the female population of China’s 2010 Census and by the age distribution of the WHO world standard population of 2001 were 3.21% and 3.03%, respectively. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of prior hysterectomy according to 5-year age groups. Among women age 25–39, 0.33% (4/1214) had no uterus (age 25–29: 0.32%; age 30–34: 0.52%; age 35–39: 0.19%). The percentage rose to 7.22% (27/374) among women age 45–49. After age 50, the prevalence of prior hysterectomy declined somewhat (figure 1). Women above the age of 40 years had a higher prevalence of prior hysterectomy compared with those aged 25–39 years (5.01% vs 0.33%, data not shown). Obesity was marginally related with a higher risk of hysterectomy (adjusted OR=1.59; 95% CI 0.99 to 2.56; body mass index (BMI) ≥28.0 vs 18.5 ≤ BMI <24.0) (table 1). History of pregnancy loss conferred a greater risk for hysterectomy (adjusted OR=1.51; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.23) (table 1).

Figure 1.

The prevalence of prior hysterectomy (%) according to 5-year age groups among 3328 rural Chinese women, 2009–2011. The numbers of women in the 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64 and 65–69 years age groups were 313, 384, 517, 633, 374, 344, 365, 330 and 68, respectively.

Table 1.

Prevalence of and risk factors for hysterectomy among women in rural Anyang, China, 2009–2011

| Variables | Hysterectomy, N (%) | No hysterectomy, N (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | p Value* |

| Total | 110 (3.31) | 3218 (96.69) | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 25–40 | 4 (3.64) | 892 (27.72) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 41–56 | 66 (60.00) | 1527 (47.45) | 9.52 (3.53 to 25.64) | 7.82 (2.87 to 21.31) | <0.001 |

| 57–69 | 40 (36.36) | 799 (24.83) | 11.04 (4.02 to 30.31) | 10.10 (3.48 to 29.32) | <0.001 |

| ptrend† | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Never married, divorced, separated or widowed | 5 (4.63) | 177 (5.59) | 1.00 | ||

| Married or cohabiting | 103 (95.37) | 2992 (94.41) | 1.24 (0.50 to 3.12) | ||

| Type of employment | |||||

| Farming | 101 (93.52) | 2845 (89.78) | 1.00 | ||

| Non-farming | 7 (6.48) | 324 (10.22) | 0.61 (0.28 to 1.32) | ||

| Education level | |||||

| Illiteracy (<1 year) or primary school (1–6 years) | 72 (66.67) | 1814 (57.33) | 1.00 | ||

| Junior high school (7–9 years) | 31 (28.70) | 1173 (37.07) | 0.67 (0.44 to 1.03) | ||

| Senior high school or above (>9 years) | 5 (4.63) | 177 (5.59) | 0.71 (0.28 to 1.79) | ||

| ptrend† | 0.085 | ||||

| Household annual income, RMB | |||||

| ≤10 000 | 23 (35.94) | 511 (30.42) | 1.00 | ||

| 10 001–29 999 | 17 (26.56) | 534 (31.79) | 0.71 (0.37 to 1.34) | ||

| ≥30 000 | 24 (37.50) | 635 (37.80) | 0.86 (0.48 to 1.54) | ||

| ptrend† | 0.643 | ||||

| Cigarette smoking | |||||

| Never | 108 (100.00) | 3160 (99.72) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 0 (0.00) | 9 (0.28) | NE | ||

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| Never | 107 (99.07) | 3163 (99.81) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 1 (0.93) | 6 (0.19) | 4.89 (0.58 to 41.33) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

| Normal weight (18.5≤ BMI <24.0) | 40 (36.70) | 1358 (44.42) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Overweight (24.0 ≤ BMI <28.0) | 34 (31.19) | 1011 (33.07) | 1.15 (0.72 to 1.84) | 1.06 (0.66 to 1.70) | 0.815 |

| Obese (BMI ≥28.0) | 34 (31.19) | 587 (19.20) | 2.01 (1.26 to 3.22) | 1.59 (0.99 to 2.56) | 0.054 |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 1 (0.92) | 101 (3.30) | 0.35 (0.05 to 2.51) | 0.38 (0.05 to 2.94) | 0.355 |

| ptrend† | 0.061 | 0.223 | |||

| Age (years) at menarche | |||||

| ≤15 | 46 (42.99) | 1394 (44.45) | 1.00 | ||

| 16–18 | 45 (42.06) | 1391 (44.36) | 0.98 (0.64 to 1.49) | ||

| ≥19 | 16 (14.95) | 351 (11.19) | 1.38 (0.77 to 2.46) | ||

| ptrend† | 0.437 | ||||

| Menstruation | |||||

| Regular | 73 (68.22) | 2223 (70.80) | 1.00 | ||

| Irregular | 34 (31.78) | 917 (29.20) | 0.88 (0.58 to 1.34) | ||

| Age (years) at first birth | |||||

| ≤22 | 53 (49.53) | 1273 (40.84) | 1.00 | ||

| 23–24 | 31 (28.97) | 1102 (35.35) | 0.68 (0.43 to 1.07) | ||

| ≥25 | 23 (21.50) | 742 (23.80) | 0.75 (0.46 to 1.23) | ||

| ptrend† | 0.166 | ||||

| Parity | |||||

| ≤2 | 53 (49.07) | 1939 (61.77) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| >2 | 55 (50.93) | 1200 (38.23) | 1.72 (1.16 to 2.53) | 1.05 (0.67 to 1.64) | 0.842 |

| History of fetal loss | |||||

| Never | 50 (45.45) | 1825 (56.71) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Ever | 60 (54.55) | 1393 (43.29) | 1.56 (1.06 to 2.30) | 1.51 (1.02 to 2.23) | 0.038 |

| Use of intrauterine contraceptive devices | |||||

| No | 29 (26.85) | 669 (21.14) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 79 (73.15) | 2495 (78.86) | 0.72 (0.47 to 1.11) | ||

| Tubal ligation | |||||

| No | 63 (58.33) | 1948 (61.57) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 45 (41.67) | 1216 (38.43) | 1.15 (0.78 to 1.69) | ||

| History of cervicitis | |||||

| Never | 91 (86.67) | 2534 (85.18) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 14 (13.33) | 441 (14.82) | 0.89 (0.50 to 1.58) | ||

| History of vaginitis | |||||

| Never | 80 (76.19) | 2410 (80.95) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 25 (23.81) | 567 (19.05) | 1.32 (0.83 to 2.09) | ||

| History of pelvic inflammation | |||||

| Never | 104 (96.30) | 2794 (93.92) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 4 (3.70) | 181 (6.08) | 0.59 (0.21 to 1.63) | ||

| History of postintercourse bleeding | |||||

| Never | 98 (91.59) | 2856 (90.96) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 9 (8.41) | 284 (9.04) | 0.92 (0.46 to 1.84) | ||

| Genital washing before sex | |||||

| Rare | 86 (79.63) | 2329 (73.52) | 1.00 | ||

| Occasional | 11 (10.19) | 400 (12.63) | 0.75 (0.39 to 1.41) | ||

| Often | 111 (10.19) | 439 (13.86) | 0.67 (0.36 to 1.28) | ||

| ptrend† | 0.162 |

*Variables that were statistically significant in univariate GEE regression analyses were included in multivariate models. Adjusted ORs, 95% CIs and p values were calculated by multivariate GEE regression model including age group, BMI, parity and history of fetal loss.

†p Values for trend were calculated by GEE regression analyses, treating categorical variables as continuous variables.

BMI, body mass index; GEE, generalised estimating equation; NE, not estimable; RMB, renminbi.

Indications and surgical types for hysterectomy

A total of 75 (68.18%, 75/110) cases provided further information on hysterectomy, with a mean age at time of hysterectomy of 44 years (SD: 7.6 years; range: 27–66 years) (see online supplementary figure S1). Of these 75 cases, 70.67% (53/75) had a hysterectomy performed for leiomyoma, 10.67% (8/75) had a hysterectomy performed for dysfunctional uterine bleeding, 1.33% (1/75) had a hysterectomy performed for cervical cancer, and 6.67% (5/75) had a hysterectomy performed for other indications (table 2). Total abdominal hysterectomy was the most common surgical technique (84.00%, 63/75), while other methods such as vaginal hysterectomy (2.67%, 2/75) and laparoscopic hysterectomy (1.33%, 1/75) each accounted for ≤3% of the total hysterectomies.

Table 2.

Indications for and types of surgery among the 75 hysterectomy cases from rural Anyang, China, 2009–2011

| Procedure | Leiomyoma | Dysfunctional uterine bleeding | Cervical cancer | Other | Total |

| N (%) | |||||

| Total abdominal hysterectomy | 49 (92.45) | 8 (100) | 1 (25) | 5 (50) | 63 (84) |

| Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy | 1 (1.89) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 2 (2.67) |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | 2 (2.67) |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy | 1 (1.89) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.33) |

| Radical hysterectomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.67) |

| Other unspecified hysterectomy | 2 (3.77) | 0 (Older age, obesity 0) | 1 (25) | 2 (20) | 5 (6.67) |

| Total | 53 (100) | 8 (100) | 4 (100) | 10 (100) | 75 (100) |

bmjopen-2016-015351supp002.pdf (4.2MB, pdf)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the prevalence of and factors associated with hysterectomy in a general population in rural China. Data from this study demonstrated that rural Chinese women had a low prevalence of hysterectomy. Obesity and history of pregnancy loss were associated with greater odds of hysterectomy. The most common indication for hysterectomy was leiomyoma, and the predominant procedure performed was abdominal hysterectomy. This investigation expands our knowledge about the epidemiological profile of hysterectomy in a low-income setting.

The overall prevalence of hysterectomy (3.3%) in our study was considerably lower than previous findings from studies conducted in developed countries such as the USA (26.2%), Ireland (22.2%) and Australia (22.0%),18–21 but closer to that identified in Taiwan (8.8%) and Singapore (7.5%).22 23 Data on hysterectomy are limited in low-income to middle-income settings. Our estimated prevalence was in the lower range reported by community-based studies from low-income and middle-income countries such as India, El Salvador and Jordan (1.7%–9.8%),3 24–31 similar to the percentage reported among women textile workers in Shanghai, China (3.9%).32 The low hysterectomy prevalence in this study population may be due to various reasons, including limited availability of gynaecology services, poor access to public/private sectors and fear of surgical operations. Additionally, low affordability of medical care can be another explanation for the low prevalence. Based on data of China’s National Health Survey in 2003, more than one-third of those who did not seek medical care while sick and over two-thirds of those who refused hospitalisation after professional referral reported ‘excessive cost’ as the major factor influencing their decisions.33 The cultural norms associated with fertility-preserving treatment may also have contributed to the relatively lower prevalence of hysterectomy.7 34 The uterus, as the childbearing organ, is seen as the essence of womanhood in China. Some individuals may feel that they are no longer women after hysterectomy. Indeed, one previous study showed that Chinese–American women who were educated in China and presumably less acculturated into the American ‘hysterectomy-prone’ culture had a low hysterectomy rate.35

Although the overall prevalence of hysterectomy was generally lower than the previously reported rates in high-resource regions, the pattern of the age distribution of prior hysterectomy prevalence was consistently similar.4 The percentage of prior hysterectomy started to increase in women aged 40–49 years and thereafter remained relatively stable, which could be due to the sharp increase in hysterectomy incidence rates in this age group.4 36 In support of this reasoning, we observed that the average age at hysterectomy was 44 years and more than one-half of all hysterectomies were done in women age 40–49 in this study. According to previous investigations, this increase may be driven by the high occurrence of uterine leiomyoma, the main indication for surgically removing the uterus, among women aged 40–49 years.36 Approximately one-quarter of hysterectomies were performed in women younger than 40 years of age in this study. Evidence on the long-term side effects of hysterectomy suggests that hysterectomies, especially those performed at young age, are associated with earlier onset of menopause and higher risk of cardiovascular disease, urinary incontinence and problems with sexual function.37–40 Research is required across China to monitor trends and track long-term health effects of hysterectomy.

For indications and surgical types for hysterectomy, similar to reports from Taiwan6 and Western countries,36 41 leiomyoma of the uterus predominated among the medical conditions leading to hysterectomy in this study population; among women undergoing hysterectomy, abdominal hysterectomy was the most frequently performed procedure, also in agreement with most previous studies.1 4 However, the frequencies at which different types of hysterectomies were performed have been found to vary markedly across populations and over time, probably due to differences in healthcare resources, surgeon experience and patient attitudes.4 18 42 According to a Cochrane review of studies mainly conducted in Western countries, vaginal hysterectomy, which has become more widely performed, appeared to be superior to laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy for benign diseases, as it has been associated with a speedier return to normal activities due to smaller incisions.42 However, there is limited evidence about the changes in hysterectomy rates over time and the relative superiority of hysterectomy approaches for addressing benign conditions in low-resource settings, and further research in this regard is needed.

In terms of predictors for hysterectomy, it should be noted that data on sociodemographic factors and behavioural characteristics as well as information about BMI status were only gathered at the time of interview; hence, whether there was any change in these questionnaire data before or after a hysterectomy, if performed, is unknown. The following discussion was based on the assumption that the information of aforementioned variables remained unchanged before the interview. In this study, prior pregnancy loss was associated with greater odds of hysterectomy; this finding is consistent with previous reports.5 9 41 Induced abortions have been commonly used in China since the 1970s as part of the national family planning programme. According to surveys conducted in China, approximately 50% of women had prior abortions, primarily aiming to limit family size.43 44 Complications such as uterine perforation resulting from surgical abortion may lead to the application of hysterectomy as a treatment option.45 In addition to being a risk factor, pregnancy loss may also be a reflection of uterine dysfunction that leads to an indication for hysterectomy. More qualitative research is needed regarding the biological and attitudinal links between prior fetal loss and hysterectomy, from both women’s and physicians’ perspectives. In terms of schooling, lower education level has been associated with a higher risk of hysterectomy; however, this association seems to vary by geographical location.2 12 41 46 47 In this study, no correlation was found between education level and hysterectomy. Whether this null risk estimate was a true lack of association or merely due to insufficient statistical power because of the small number of hysterectomy cases and low proportion of women with high education levels included in our analysis is unclear. Concerning BMI, a higher hysterectomy frequency was observed in obese women in this study, confirming findings from other studies.48 The correlation between obesity and hysterectomy can be partially explained by the fact that obesity elevates the risk of many gynaecological conditions that may result in hysterectomy.49 For instance, obesity has been reported to be associated with pelvic organ prolapse and uterine fibroids, which are common indications for hysterectomy.50 Obese women are also more likely to develop endometrial carcinomas and pelvic inflammatory diseases, which are less common indications for hysterectomy.49 Again, however, whether BMI status varied with undergoing hysterectomy is not determinable from the data at hand. Further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate the factors affecting hysterectomy.

This study has some strengths and limitations. As regional or national databases in rural China are not as readily available as they are in developed countries, the use of hysterectomy status data ascertained by a gynaecologist in a cervical cytology screening programme among rural Chinese women enabled us to evaluate the prevalence and predictors of hysterectomy in this area. Thus, one of the main strengths of this study is the population-based nature and low-resource setting. The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the possibility of a selection bias (eg, bias introduced by exclusion of individuals with a history of cervical cancer) may reduce the generalisability of our findings to a wider population. Second, due to the response bias of participants, there is no assurance that the epidemiological profile of hysterectomy observed here would hold true for the region as a whole. Third, self-reported maternal and reproductive characteristics may be subject to recall bias. Additionally, the small number of hysterectomy cases may have affected the precision of our assessment of the predictors of hysterectomy. Finally, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, a temporal relationship cannot be inferred. Despite these limitations, our study still provides baseline information on the prevalence and predictors of hysterectomy, as well as indications for and procedures used in hysterectomies in rural China.

In summary, rural Chinese women had a relatively low prevalence of hysterectomy, which were largely performed abdominally for leiomyoma. Older age, obesity and history of fetal loss were associated with increased risk of hysterectomy among this study population. These findings provide insights into the hysterectomy epidemiology in lower resource areas. Further studies are needed to monitor the trend of incidence rate of hysterectomy and modes of surgery over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Robert S Burk for editing and correction of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: YK and HC were involved in the design and conduct of the survey. YP, YoL, FL, QD, XL, ML, ZH, YiL, JL, TN, CG, RX and LZ were involved in conducting the field work. FL and CZ performed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Patient consent form required by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Oncology, Peking University was obtained from each participant.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Oncology, Peking University (Approval number: 2006020). All participants provided written informed consent. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Anonymous datasets are available from the corresponding author (keyang@bjmu.edu.cn).

References

- 1. Garry R. The future of hysterectomy. BJOG 2005;112:133–9. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koepsell TD, Weiss NS, Thompson DJ, et al. Prevalence of prior hysterectomy in the Seattle-Tacoma area. Am J Public Health 1980;70:40–7. 10.2105/AJPH.70.1.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barghouti FF, Yasein NA, Jaber RM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence among jordanian women: impact on their life. Health Care Women Int 2013;34:1015–23. 10.1080/07399332.2011.646372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Merrill RM. Hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 1997 through 2005. Med Sci Monit 2008;14:CR24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dharmalingam A, Pool I, Dickson J. Biosocial determinants of hysterectomy in New Zealand. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1455–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang C, Mao CL, Hu YH. Prevalence of hysterectomy of Chinese women in Taiwan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1996;52:73–4. 10.1016/0020-7292(95)02562-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stang A, Merrill RM, Kuss O. Hysterectomy in Germany: a DRG-based nationwide analysis, 2005-2006. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011;108:508–14. 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stang A, Kluttig A, Moebus S, et al. Educational level, prevalence of hysterectomy, and age at amenorrhoea: a cross-sectional analysis of 9536 women from six population-based cohort studies in Germany. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:10 10.1186/1472-6874-14-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang Y, Lee ET, Cowan LD, et al. Hysterectomy prevalence and cardiovascular disease risk factors in American Indian women. Maturitas 2005;52:328–36. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Desai S, Campbell OM, Sinha T, et al. Incidence and determinants of hysterectomy in a low-income setting in Gujarat, India. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:68–78. 10.1093/heapol/czw099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weaver F, Hynes D, Goldberg JM, et al. Hysterectomy in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:880–4. 10.1097/00006250-200106000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Byles JE, Mishra G, Schofield M. Factors associated with hysterectomy among women in Australia. Health Place 2000;6:301–8. 10.1016/S1353-8292(00)00011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeCherney AH, Bachmann G, Isaacson K, et al. Postoperative fatigue negatively impacts the daily lives of patients recovering from hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:51–7. 10.1097/00006250-200201000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu F, Guo F, Zhou Y, et al. The Anyang Esophageal Cancer Cohort Study: study design, implementation of fieldwork, and use of computer-aided survey system. PLoS One 2012;7:e31602 10.1371/journal.pone.0031602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chinese Ministry of Health and Family Planning. NCMS Progress in 2012 and key work in 2013. Chinese Ministry of Health and Family Planning, 2013. http://wwwnhfpcgovcn/jws/hzyl/list_3shtml [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986;42:121–30. 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, et al. GPE discussion paper series: No. 31: age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spilsbury K, Semmens JB, Hammond I, et al. Persistent high rates of hysterectomy in Western Australia: a population-based study of 83 000 procedures over 23 years. BJOG 2006;113:804–9. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00962.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, et al. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988-1990. Obstet Gynecol 1994;83:549–55. 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McPherson K, Strong PM, Epstein A, et al. Regional variations in the use of common surgical procedures: within and between England and Wales, Canada and the United States of America. Soc Sci Med A 1981;15(3 Pt 1):273–88. 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90011-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Keep PA, Wildemeersch D, Lehert P. Hysterectomy in six European countries. Maturitas 1983;5:69–75. 10.1016/0378-5122(83)90001-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hsieh CH, Lee MS, Lee MC, et al. Risk factors for urinary incontinence in Taiwanese women aged 20-59 years. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2008;47:197–202. 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lam JS, Tay WT, Aung T, et al. Female reproductive factors and major eye diseases in Asian women -the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2014;21:92–8. 10.3109/09286586.2014.884602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaur S, Walia I, Singh A. How menopause affects the lives of women in suburban Chandigarh, India. Climacteric 2004;7:175–80. 10.1080/13697130410001713779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shakhatreh FM. Epidemiology of urinary incontinence in Jordanian women. Saudi Med J 2005;26:830–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patel V, Tanksale V, Sahasrabhojanee M, et al. The burden and determinants of dysmenorrhoea: a population-based survey of 2262 women in Goa, India. BJOG 2006;113:453–63. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ozel B, Borchelt AM, Cimino FM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic floor symptoms in women in rural El Salvador. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007;18:1065–9. 10.1007/s00192-006-0292-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh A, Arora AK. Why Hysterectomy Rate are Lower in India. Indian J Community Med 2008;33:196–7. 10.4103/0970-0218.42065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bhasin SK, Roy R, Agrawal S, et al. An epidemiological study of major surgical procedures in an urban population of East delhi. Indian J Surg 2011;73:131–5. 10.1007/s12262-010-0198-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Desai S, Sinha T, Mahal A. Prevalence of hysterectomy among rural and urban women with and without health insurance in Gujarat, India. Reprod Health Matters 2011;19:42–51. 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37553-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sarna A, Friedland BA, Srikrishnan AK, et al. Sexually transmitted infections and reproductive health morbidity in a cohort of female sex workers screened for a microbicide feasibility study in Nellore, India. Glob J Health Sci 2013;5:139–49. 10.5539/gjhs.v5n3p139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wong EY, Ray R, Gao DL, et al. Reproductive history, occupational exposures, and thyroid cancer risk among women textile workers in Shanghai, China. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2006;79:251–8. 10.1007/s00420-005-0036-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu D, Tsegai D. The New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) and its implications for access to health care and medical expenditure: evidence from rural China ZEF- Discussion Papers on Development Policy No 155. Bonn: Center for Development Research, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Broder MS, Kanouse DE, Mittman BS, et al. The appropriateness of recommendations for hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:199–205. 10.1097/00006250-200002000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Powell LH, Meyer P, Weiss G, et al. Ethnic differences in past hysterectomy for benign conditions. Womens Health Issues 2005;15:179–86. 10.1016/j.whi.2005.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jacobson GF, Shaber RE, Armstrong MA, et al. Hysterectomy rates for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1278–83. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000210640.86628.ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hunter MS, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, et al. Prevalence, frequency and problem rating of hot flushes persist in older postmenopausal women: impact of age, body mass index, hysterectomy, hormone therapy use, lifestyle and mood in a cross-sectional cohort study of 10,418 British women aged 54-65. BJOG 2012;119:40–50. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03166.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hoga LA, Higashi AB, Sato PM, et al. Psychosexual perspectives of the husbands of women treated with an elective hysterectomy. Health Care Women Int 2012;33:799–813. 10.1080/07399332.2011.646370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2005;112:956–62. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yeh JS, Cheng HM, Hsu PF, et al. Hysterectomy in young women associates with higher risk of stroke: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:2616–21. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brett KM, Marsh JV, Madans JH. Epidemiology of hysterectomy in the United States: demographic and reproductive factors in a nationally representative sample. J Womens Health 1997;6:309–16. 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD003677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sanderson M, Shu XO, Jin F, et al. Abortion history and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Int J Cancer 2001;92:899–905. 10.1002/ijc.1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye Z, Gao DL, Qin Q, et al. Breast cancer in relation to induced abortions in a cohort of Chinese women. Br J Cancer 2002;87:977–81. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grimes DA, Flock ML, Schulz KF, et al. Hysterectomy as treatment for complications of legal abortion. Obstet Gynecol 1984;63:457–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Treloar SA, Do KA, O'Connor VM, et al. Predictors of hysterectomy: an Australian study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:945–54. 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70666-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nagata C, Takatsuka N, Kawakami N, et al. Soy product intake and premenopausal hysterectomy in a follow-up study of Japanese women. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:773–7. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fitzgerald DM, Berecki-Gisolf J, Hockey RL, et al. Hysterectomy and weight gain. Menopause 2009;16:279–85. 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181865373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goodman MT, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, et al. Diet, body size, physical activity, and the risk of endometrial Cancer. Cancer Res 1997;57:5077–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pandey S, Bhattacharya S. Impact of obesity on gynecology. Womens Health 2010;6:107–17. 10.2217/whe.09.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015351supp001.pdf (183.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015351supp002.pdf (4.2MB, pdf)