Abstract

Objectives

The Bhutanese Screening Programme recommends a Pap smear every 3 years for women aged 25–65 years, and coverage ranges from 20% to 60%, being especially challenging in rural settings. The ‘REACH-Bhutan’ study was conducted to assess the feasibility and outcomes of a novel approach to cervical cancer screening in rural Bhutan.

Design

Cross-sectional, population-based study of cervical cancer screening based on the careHPV test on self-collected samples.

Setting

Women were recruited in rural primary healthcare centres, that is, Basic Health Units (BHU), across Bhutan.

Participants

Overall, 3648 women aged 30–60 were invited from 15 BHUs differing in accessibility, size and ethnic composition of the population.

Interventions

Participants provided a self-collected cervicovaginal sample and were interviewed. Samples were tested using careHPV in Thimphu (the Bhutanese capital) referral laboratory.

Main outcome measures

Screening participation by geographic area, centre, age and travelling time. Previous screening history and careHPV positivity by selected characteristics of the participants.

Results

In April/May 2016, 2590 women (median age: 41) were enrolled. Study participation was 71% and significantly heterogeneous by BHU (range: 31%–96%). Participation decreased with increase in age (81% in women aged 30–39 years; 59% in ≥50 years) and travelling time (90% in women living <30 min from the BHU vs 62% among those >6 hours away). 50% of participants reported no previous screening, with the proportion of never-screened women varying significantly by BHU (range: 2%–72%). 265 women (10%; 95% CI 9% to 11%) were careHPV positive, with a significant variation by BHU (range: 5%–19%) and number of sexual partners (prevalence ratio for ≥3 vs 0–1, 1.55; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.27).

Conclusions

Community-based cervical cancer screening by testing self-collected samples for human papillomavirus (HPV) can achieve high coverage in rural Bhutan. However, solutions to bring self-collection, HPV testing and precancer treatment closer to the remotest villages are needed.

Keywords: Cervical cancer screening, self-collection, careHPV, rural population, Bhutan

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study was conducted countrywide in a range of rural primary healthcare centres, which varied in accessibility, size and ethnic composition of the target population.

The target population of each centre was enumerated on the basis of up-to-date and detailed demographic surveys.

A reliable local mobile data network ensured timely and effective study coordination, data collection and quality controls.

The proposed diagnostic and treatment solutions presented specific challenges and were less reliable than expected.

Introduction

Cervical cancer represents the most common cancer among females in Bhutan, with an age-standardised incidence rate of approximately 13 cases per 100 000 person-years.1 The country is strongly engaged in the prevention of cervical cancer. In the year 2000, the Ministry of Health launched a national cytology-based screening programme, and a Pap smear is currently recommended every 3 years to women aged 25–65 years.2 In the year 2010, Bhutan was the first low/middle-income country to initiate a successful national vaccination programme against human papillomavirus (HPV) with >90% coverage in girls aged 12–18 years.3 Conversely, screening coverage is much lower and fairly heterogeneous across the country, ranging from 20% to 60% of the target population in different provinces.4 5 In rural areas, where approximately 60% of the Bhutanese live,6 cytology-based screening campaigns are occasionally conducted but coverage remains poor,4 and follow-up and treatment of screening-positive women is challenging.

Organised screening programmes are demanding in terms of administrative, human, financial and logistic resources. Pap smear-based programmes require frequent visits, trained staff and strict quality control. In contrast, HPV-based screening allows for longer screening intervals,7 8 self-sampling9 and automation of the diagnostic procedure. It is therefore an attractive option to improve the acceptability and cost-effectiveness of screening.10

In 2016, the Ministry of Health of Bhutan and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) implemented the ‘REACH-Bhutan’ study to assess the feasibility, outcomes and challenges of cervical cancer screening based on the careHPV test on self-collected samples among women aged 30–60 years in rural areas of the country. In the current report, we describe the study design, target population, recruitment and sample collection methods, key characteristics of study participants and patterns of participation. Details on the performance of careHPV testing and clinical management of careHPV-positive women will be reported in future publications.

Material and methods

Study population and recruitment

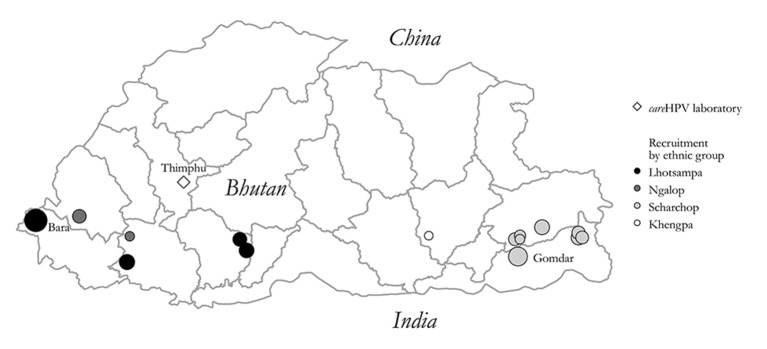

Our study targeted women aged 30–60 years living in rural areas; recruitment and sample collection took place from April to May 2016 in Basic Health Units (BHUs), the facilities that provide primary healthcare to the Bhutanese population. The Bhutanese principal investigator (UT) selected 15 BHUs that differed by accessibility, size and ethnic composition of the served population (figure 1). Lists of household members in each village were obtained from the BHU survey produced yearly for demographic purposes.

Figure 1.

Map of Bhutan with study sites and predominant ethnic groups. The size of each dot is proportional to the size of the target population of each centre.

Local health workers (HWs) familiar with community mobilisation were instructed by the principal investigator in the specifics of self-sampling for cervical screening, and visited the villages served by the selected BHUs to invite eligible women to come to the BHU to participate in the study on specified dates. The benefits of cervical cancer screening and the purposes of the study were explained to the women during public invitation sessions. All women from a given village were invited to attend screening at the BHUs on the same date. Pregnant women, women with mental disability, who had undergone hysterectomy or planned to leave the study area in the next 6 months were not eligible.

On the appointment date, two or three HWs and one of the two mobile study teams (one for East and one for West Bhutan, each composed of two nurses and supervised by a gynaecologist) provided additional information on the study, collected an informed consent form and administered a short electronic questionnaire on the BHU’s premises. The entire process required less than 20 min and certain BHUs were able to manage more than 100 women per day. Whenever possible, the recently introduced national citizenship identification number, which uniquely identifies Bhutanese citizens, and at least one mobile telephone number were recorded for follow-up purposes.

Sample collection, transportation and laboratory analysis

Each participant was asked to provide a self-collected cervicovaginal sample using a careBrush. They were instructed to insert the brush deep into the vagina and rotate it three to five times before dipping it in a tube containing careHPV collection medium. The study team nurse provided guidance to the participants on how to perform self-collection but did not attend the self-collection procedure. Tubes were then stored in fridges until they were transported in cool boxes to the central laboratory of Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital in Thimphu, within 2 weeks. Samples were stored at ~4°C and an aliquot was tested using the careHPV platform (Qiagen Corporation, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The careHPV test is a validated signal-amplification, rapid batch diagnostic test for the detection of DNA of 13 high-risk HPV types (HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) and HPV66.11 careHPV results were communicated by the central laboratory as soon as possible to each BHU (after a median of 11 days; IQR: 9 to 33 days) to arrange follow-up of careHPV-positive women and of a random fraction of careHPV-negative women, as a quality control measure.

Data collection and statistical analyses

All information on study participants and biological samples were collected and stored on portable electronic devices. Whenever a mobile data network was accessible, the stored data were uploaded to the IARC server and portable devices were synchronised with the most recent version of the study database. The distribution of the target population in each BHU by age group and by village of residence was obtained from the demographic survey conducted in year 2015. Travelling time was estimated from each village of residence to the corresponding BHU. On account of the sociogeographic characteristics of the study areas, most women had to reach the BHU on foot. We subdivided the travelling time into seven categories (ie, <30 min, 30 to 59 min, 1 hour to 1 hour 59 min, 2 hours to 2 hours 59 min, 3 hours to 3 hours 59 min, 4 hours to 5 hours 59 min and 6 or more hours) and fitted a mixed-effect logistic model to data to assess the influence of travelling time on study participation with BHUs as clusters.

Among participating women, we assessed prevalence ratios (PR) and corresponding 95% CI for lack of previous cervical cancer screening and careHPV positivity according to selected characteristics using binomial regression models with a log link and adjustment for age group (30–39, 40–49 and ≥50 years) and BHU of recruitment, as appropriate. For each variable of interest, missing or undisclosed (ie, labelled as ‘prefer not to answer’) information were treated as not informative and excluded from the analyses.

Results

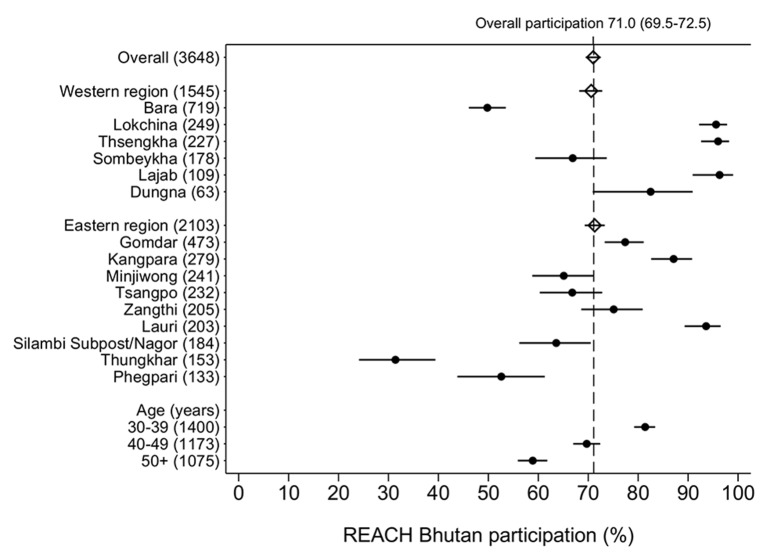

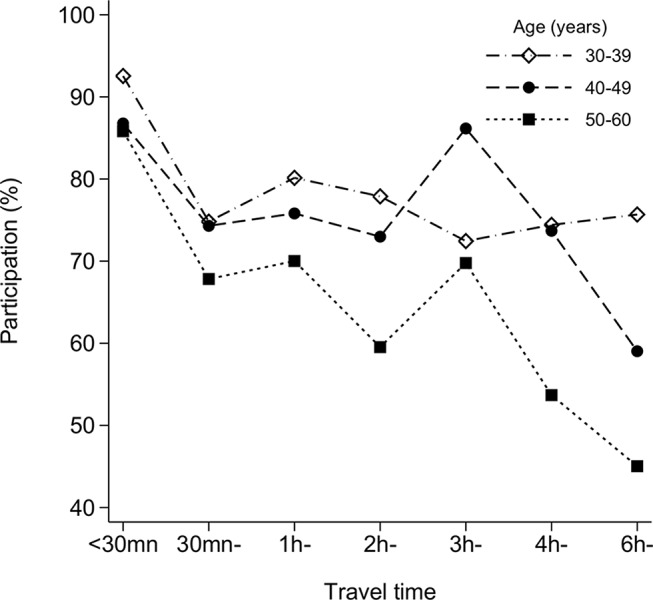

Out of 15 BHUs included in ‘REACH-Bhutan’, six are located in West Bhutan and nine in East Bhutan (figure 1). They serve a total of 3648 women aged 30–60 years (figure 2). Overall participation was 71% (95% CI 69.5% to 72.5%) and was similar in the West and the East. It was, however, significantly heterogeneous by BHU (range: 31%–96%, I2 99%, p<0.001), and age group (81% in women aged 30–39 years but only 59% in ≥50 years). Participation steadily decreased with the increase in travelling time from village to BHU being 90% (95% CI 84% to 94%) for women living less than 30 min from the BHU but 62% (95% CI 50% to 73%) among those 6 hours away or more (see supplementary data 1). The influence of travelling time strongly increased with a woman’s age: the drop in participation between 30 min and 6 hours was from 93% (95% CI 87% to 96%) to 76% (95% CI 64% to 84%) among women aged 30–39 years, but from 86% (95% CI 75% to 92%) to 45% (95% CI 30% to 62%) among women ≥50 years (figure 3). The village of residence was not reported by six women or did not belong to the BHU catchment area (seven women). These women did not contribute to the analysis reported in figure 3.

Figure 2.

Participation (%) and corresponding 95% CI by Basic Health Unit, region, and age group, Bhutan, 2016.

Figure 3.

Effect of travel time (on foot) on participation in REACH-Bhutan, by age group, Bhutan, 2016.

bmjopen-2017-016309supp001.pdf (115.3KB, pdf)

A total 2590 women accepted the invitation and came to a BHU (median age: 41 years; IQR: 35 to 49 years). Ninety-nine per cent belonged to four ethnic groups: Scharchop (55%); Lhotsampa (27%); Ngalop (13%); and Khengpa (4%); each group predominating in at least one BHU (figure 1). All but two women provided a telephone number and 60% provided their identity card number. Most women stated that self-sampling was easy to perform (96%) and painless (90%). Macroscopic blood traces were observed in 3.5% of sample of non-menstruating women (data not shown).

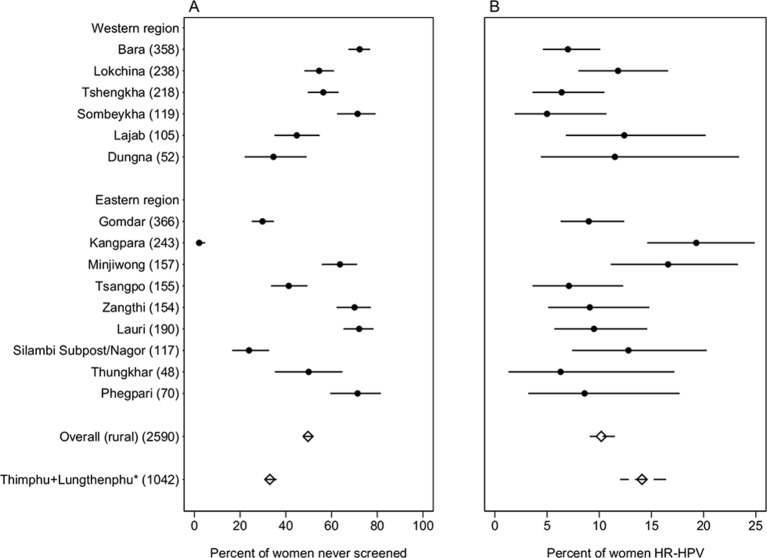

Fifty per cent of participants reported having had previous screening (figure 4A) and, among them, 83% had had a Pap smear in the last 4 years (data not shown). The proportion of never-screened women varied across individual BHUs (range: 2%–72%, I2=99%, p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Per cent of (A) lack of previous cervical cancer screening; and (B) careHPV positivity by Basic Health Unit and overall in rural areas and in Thimphu, Bhutan, 2016. *Women aged 30–60 years in Tshomo et al.20 HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus.

Table 1 shows the characteristics that were significantly associated with lack of screening, that is, age group (PR for ≥50 vs 30–39 years, 1.36; 95% CI 1.26 to 1.47); region (PR for West vs East, 2.84; 95% CI 2.05 to 3.95); travelling time from village to BHU (PR for ≥6 hours vs <1 hour, 1.53; 95% CI 1.38 to 1.69); ethnicity (PR vs Scharchop, 1.65; 95% CI 1.52 to 1.80 for Ngalop; 1.41; 95% CI 1.29 to 1.53 for Lhotsampa; and 0.58; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.81 for Khengpa); educational level (PR for literate vs illiterate, 0.85; 95% CI 0.73 to 0.99); occupation (PR for shopkeepers/saleswoman/manual worker vs farmer/housewives, 0.56; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.90); marital status (PR for never married vs married, 1.35; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.71); and nulliparity (PR for 0 vs ≥3, 1.25; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.49). Lifetime number of sexual partners, age at first sexual intercourse and careHPV positivity were unrelated to screening history (table 1).

Table 1.

PRs for lack of previous cervical cancer screening and corresponding 95% CI according to selected characteristics, Bhutan, 2016

| Characteristic | N tested | Never screened n (%) | Adjusted PR* | 95% CI |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 30–39 | 1139 | 497 (43.6) | 1 | – |

| 40–49 | 818 | 407 (49.8) | 1.14 | 1.05 to 1.24 |

| ≥50 | 633 | 383 (60.5) | 1.36 | 1.26 to 1.47 |

| for trend | p<0.001 | |||

| Region | ||||

| East | 1500 | 625 (41.7) | 1 | – |

| West | 1090 | 662 (60.7) | 2.84 | 2.05 to 3.95 |

| Travel time from village to BHU (hours)† | ||||

| <1 | 656 | 285 (43.5) | 1 | – |

| 1–5 | 1287 | 576 (44.8) | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.12 |

| Missing | 6 | 4 (66.7) | – | – |

| ≥6 | 641 | 422 (65.8) | 1.53 | 1.38 to 1.69 |

| for trend | p<0.001 | |||

| Ethnicity† | ||||

| Scharchop | 1435 | 615 (42.9) | 1 | – |

| Ngalop | 340 | 236 (69.4) | 1.65 | 1.52 to 1.80 |

| Lhotsampa | 686 | 401 (58.5) | 1.41 | 1.29 to 1.53 |

| Khengpa | 113 | 26 (23.0) | 0.58 | 0.41 to 0.81 |

| Other | 16 | 9 (56.3) | 1.49 | 0.97 to 2.31 |

| Education level | ||||

| Illiterate | 2372 | 1191 (50.2) | 1 | – |

| Literate | 218 | 96 (44.0) | 0.85 | 0.73 to 0.99 |

| Current occupation | ||||

| Farmer/ housewife | 2488 | 1254 (50.4) | 1 | – |

| Shopkeeper/saleswoman/manual worker | 53 | 12 (22.6) | 0.56 | 0.34 to 0.90 |

| Clerical staff/teacher/health worker/nun | 49 | 21 (42.9) | 0.97 | 0.72 to 1.31 |

| Marital status† | ||||

| Married/living as married | 2390 | 1175 (49.2) | 1 | – |

| Never married | 21 | 16 (76.2) | 1.35 | 1.07 to 1.71 |

| Widow/separated/divorced | 179 | 96 (53.6) | 1.05 | 0.92 to 1.21 |

| Number of pregnancies† | ||||

| 0 | 67 | 43 (64.2) | 1.25 | 1.05 to 1.49 |

| 1–2 | 604 | 285 (47.2) | 1.03 | 0.94 to 1.14 |

| ≥3 | 1919 | 959 (50.0) | 1 | – |

| for trend | p=0.057 | |||

| Lifetime number of sexual partners | ||||

| 0–1 | 2020 | 983 (48.7) | 1 | – |

| 2 | 341 | 166 (48.7) | 0.97 | 0.88 to 1.08 |

| ≥3 | 214 | 126 (58.9) | 0.98 | 0.88 to 1.09 |

| Prefer not to answer | 15 | 12 (80.0) | – | – |

| for trend | p=0.601 | |||

| Age at first sexual intercourse (years)‡ | ||||

| 9–14 | 245 | 124 (50.6) | 1 | – |

| 15–16 | 515 | 235 (45.6) | 0.93 | 0.81 to 1.06 |

| 17–19 | 968 | 452 (46.7) | 1.00 | 0.89 to 1.12 |

| ≥20 | 707 | 365 (51.6) | 1.02 | 0.91 to 1.15 |

| Prefer not to answer/unknown | 143 | 101 (70.6) | – | – |

| for trend | p=0.151 | |||

| HPV infection | ||||

| Negative | 2325 | 1168 (50.2) | 1 | – |

| Positive | 265 | 119 (44.9) | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.13 |

*Adjusted for age (three classes: 30–39; 40–49; 50+) and BHU as appropriate.

†Adjusted for age only —when adjusted for BHU, model does not converge.

‡Among sexually active women.

BHU, Basic Health Units; HPV, human papillomavirus; PR, prevalence ratio.

Overall, 265 women (10%; 95% CI 9% to 11%) were careHPV positive with a significant variation by BHU (range: 5%–19%, I2=63%, p<0.001) (figure 4B). Table 2 shows the relationship between careHPV positivity and various women’s characteristics. Significant risk factors for HPV positivity included region of Bhutan (PR for West vs East, 0.55; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.00), marital status (PR for widow, separated or divorced vs married, 1.71; 95% CI 1.21 to 2.41), number of pregnancies (PR for 1–2 vs ≥3, 1.49; 95% CI 1.15 to 1.93) and lifetime number of sexual partners (PR for ≥3 vs 0–1, 1.55; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.27). careHPV positivity was not significantly associated with age, ethnicity, educational level, occupation, age at first sexual intercourse and lack of previous screening (table 2).

Table 2.

PR for high-risk HPV positivity and corresponding 95% CI according to selected characteristics, Bhutan, 2016

| Characteristic | N tested | careHPV positive n (%) | Adjusted PR* | 95% CI |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 30–39 | 1139 | 129 (11.3) | 1 | – |

| 40–49 | 818 | 76 (9.3) | 0.80 | 0.62 to 1.05 |

| ≥50 | 633 | 60 (9.5) | 0.79 | 0.59 to 1.05 |

| for trend | p=0.073 | |||

| Region | ||||

| East | 1500 | 173 (11.5) | 1 | – |

| West | 1090 | 92 (8.4) | 0.55 | 0.30 to 1.00 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Scharchop | 1435 | 164 (11.4) | 1 | – |

| Ngalop | 340 | 28 (8.2) | 0.68 | 0.31 to 1.49 |

| Lhotsampa | 686 | 58 (8.5) | 0.67 | 0.33 to 1.38 |

| Khengpa | 113 | 15 (13.3) | 1.80 | 0.31 to 10.5 |

| Other | 16 | 0 (0) | – | – |

| Education level | ||||

| Illiterate | 2372 | 238 (10.0) | 1 | – |

| Literate | 218 | 27 (12.4) | 1.33 | 0.90 to 1.95 |

| Current occupation | ||||

| Farmer/housewife | 2488 | 253 (10.2) | 1 | – |

| Shopkeeper/saleswoman/manual worker | 53 | 3 (5.7) | 0.56 | 0.18 to 1.68 |

| Clerical staff/teacher/health worker/nun | 49 | 9 (18.4) | 1.65 | 0.90 to 3.01 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/living as married | 2390 | 232 (9.7) | 1 | – |

| Never married | 21 | 3 (14.3) | 1.53 | 0.54 to 4.38 |

| Widow/separated/divorced | 179 | 30 (16.8) | 1.71 | 1.21 to 2.41 |

| Number of pregnancies | ||||

| 0 | 67 | 8 (11.9) | 1.29 | 0.66 to 2.49 |

| 1–2 | 604 | 83 (13.7) | 1.49 | 1.15 to 1.93 |

| ≥3 | 1919 | 174 (9.1) | 1 | – |

| for trend | p=0.007 | |||

| Lifetime number of sexual partners | ||||

| 0–1 | 2020 | 198 (9.8) | 1 | – |

| 2 | 341 | 36 (10.6) | 1.20 | 0.85 to 1.69 |

| ≥3 | 214 | 31 (14.5) | 1.55 | 1.05 to 2.27 |

| Prefer not to answer | 15 | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| for trend | p=0.022 | |||

| Age at first sexual intercourse (years)† | ||||

| 9–14 | 245 | 21 (8.6) | 1 | – |

| 15–16 | 515 | 48 (9.3) | 1.05 | 0.64 to 1.71 |

| 17–19 | 968 | 109 (11.3) | 1.20 | 0.76 to 1.89 |

| ≥20 | 707 | 72 (10.2) | 1.11 | 0.69 to 1.79 |

| Prefer not to answer/unknown | 143 | 14 (9.8) | – | – |

| for trend | p=0.576 | |||

| History of Pap smear (years) | ||||

| Ever | 1303 | 146 (11.2) | 1 | – |

| Never | 1287 | 119 (9.3) | 1.06 | 0.81 to 1.39 |

*Adjusted for age (three classes: 30–39; 40–49: 50+) and BHU as appropriate.

†Among sexually active women.

BHU, Basic Health Units; HPV, human papillomavirus; PR, prevalence ratio.

Discussion

The findings from ‘REACH-Bhutan’ show that community-based cervical cancer screening using self-collected samples and careHPV test is feasible in BHUs and can achieve high coverage in rural Bhutan. Our cross-sectional study (online supplementary data 2), therefore, can be added to an increasing number of evaluations of the implementation of careHPV screening in underserved populations of Asia,12–14 Africa15–17 and Latin America.18 19

bmjopen-2017-016309supp002.doc (85KB, doc)

Seventy per cent of women from rural communities responded favourably to the invitation to come to their BHU to undergo HPV screening. In comparison, in Thimphu, the Bhutanese capital, only 33% (95% CI 29 to 37) of invited women of the same age group accepted to take part in a study of clinician-collected samples.5 However, participation significantly decreased with increasing age and travelling time between the village of residence and the BHU. The negative effect of living far away from a BHU was especially strong among older women. Furthermore, older age and large distance from BHUs were confirmed to be risk factors for lack of previous screening among the women who participated in our present study (table 1).

The large majority of study participants reported to be illiterate farmers or housewives, currently married and sexually active. One-fifth reported two sexual partners or more, and 74% three children or more. Among study participants, 50% had never been screened before, confirming that rural areas are underserved compared with Thimphu, where 33% (95% CI 30 to 36) of study participants aged 30–60 years had never been screened.5 Despite the remarkable sociodemographic homogeneity of the rural communities included participation in ‘REACH-Bhutan’ and history of previous screening among participating women were significantly different among BHUs pointing to different levels of success in application of the national guidelines.

The varying degree of participation in our current study and of previous screening across BHUs may be also related to differences in ethnic composition. Indeed, lack of previous screening was significantly more frequent among women who belonged to the Lhotsampa (mostly Hindus) and Ngalop (mostly Buddhist) ethnic groups. It is, however, unclear whether Lhotsampa and Ngalop were more reluctant to be screened or lived in areas where BHUs were less committed to screening. For example, in the large BHU of Bara, at the western border with India, there was a suggestion that a historical absence of female HWs had had a negative impact on cervical screening attendance. The few literate women and those who were shopkeepers or manual workers reported more screening attendance.

Ten per cent of women were careHPV positive, that is, a percentage only slightly lower than that found in Thimphu in the same age group, that is, 14.1% (95% CI 12.0 to 16.4).20 Lifetime number of sexual partners, being widowed, separated or divorced and having had one or two children (as compared with three) were significantly associated with HPV positivity as reported in previous IARC HPV surveys.21 22 Women in West Bhutan were less likely to be HPV positive than their counterparts in the east of the country and this finding is likely to reflect differences in lifestyle sexual habits across rural communities or ethnic groups. In fact, the percentage of women who reported two or more sexual partners was 15% in the West versus 26% in the East.

The main strengths of the present study are the inclusion of a large number of women from many rural villages and the relatively high and accurately estimated participation of invited women aged 30–60 years. We developed an mHealth platform and relied on the local mobile data network to ensure a timely and effective coordination of BHU HWs and mobile study teams across Bhutan, and to manage data collection, transmission and real-time quality controls.23 24 Furthermore, virtually all study participants had access to at least one mobile phone, greatly simplifying their recall for follow-up visits.

However, study implementation was also characterised by logistic and technological challenges. For example, although the central laboratory in Thimphu was able to deliver careHPV results to each BHU in a median of 11 days after screening, the careHPV platform turned out to be less reliable than expected and, even after completion of the initial training period, there still continued to be substantial wastage due to invalid careHPV runs. In addition, the original plan of rapidly recalling women and offering them colposcopy triage and, if necessary, cryotherapy in each BHU was hindered by difficulties in transport and/or malfunction of cryotherapy equipment.

At the end of May 2017, 251 (95%) careHPV-positive women had had a follow-up visit and 225 had undergone either cryotherapy (n=91) or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (n=134). Histological ascertainment of cervical specimens from these women (as well as from a subset of careHPV-negative women) is still ongoing, and clinical outcomes will be the subject of a future publication.

Conclusion

The ‘REACH-Bhutan’ study shows both the readiness of the Bhutanese Health System and the willingness and resilience of Bhutanese women to comply with cervical cancer screening algorithms based on self-collection for HPV testing. It also highlights, however, the need to find new solutions to specific challenges, such as bringing self-collection even closer to women, especially older ones living in the remotest areas, possibly in coordination with the decentralised offer of other primary healthcare activities, for example, child vaccination, which are regularly brought from BHUs to villages.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: All authors thank the participating women and acknowledge the excellent fieldwork performed by doctors and healthcare workers in Bhutan. We also thank Mr Damien Georges for technical assistance.

Contributors: IB, ST, SF, GMC and UT conceived and designed the study. IB, SF, GMC and UT drafted the manuscript. ST, TC, FL, VT and MP critically revised the manuscript. All authors substantially contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number OPP1053353).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained from patients.

Ethics approval: The present study had the approval of both the Research Ethical Board of the Bhutan Ministry of Health and the IARC Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Ervik M, Lam F, Ferlay J, et al. . Cancer Today Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2016. http://gco.iarc.fr/today (accessed 11 November 2016).

- 2. Dhendup T, Tshering P. Cervical Cancer knowledge and screening behaviors among female university graduates of year 2012 attending national graduate orientation program, Bhutan. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:44 10.1186/1472-6874-14-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dorji T, Tshomo U, Phuntsho S, et al. . Introduction of a National HPV vaccination program into Bhutan. Vaccine 2015;33:3726–30. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health. National Health Survey. Thimphu, Bhutan: Ministry of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baussano I, Tshomo U, Clifford GM, et al. . Cervical cancer screening program in Thimphu, Bhutan: population coverage and characteristics associated with screening attendance. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:147 10.1186/s12905-014-0147-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The World Bank. Rural population. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=BT (accessed 11 January 2017).

- 7. Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, et al. . European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Second edition--summary document. Ann Oncol 2010;21:448–58. 10.1093/annonc/mdp471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. . Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014;383:524–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arrossi S, Thouyaret L, Herrero R, et al. . Effect of self-collection of HPV DNA offered by community health workers at home visits on uptake of screening for cervical cancer (the EMA study): a population-based cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e85–e94. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70354-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsu V, Jerónimo J. Saving the world's women from cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2509–11. 10.1056/NEJMp1604113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qiao YL, Sellors JW, Eder PS, et al. . A new HPV-DNA test for cervical-cancer screening in developing regions: a cross-sectional study of clinical accuracy in rural China. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:929–36. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70210-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Qiao YL, Sellors JW, Eder PS, et al. . A new HPV-DNA test for cervical-cancer screening in developing regions: a cross-sectional study of clinical accuracy in rural China. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:929–36. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70210-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tuerxun G, Yukesaier A, Lu L, et al. . Evaluation of careHPV, Cervista Human Papillomavirus, and Hybrid Capture 2 methods in diagnosing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 2+ in Xinjiang Uyghur Women. Oncologist 2016;21:825–31. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Labani S, Asthana S. Age-specific performance of careHPV versus Papanicolaou and visual inspection of cervix with acetic acid testing in a primary cervical cancer screening. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:72–7. 10.1136/jech-2015-205851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Obiri-Yeboah D, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Djigma F, et al. . Options in human papillomavirus (HPV) detection for cervical cancer screening: comparison between full genotyping and a rapid qualitative HPV-DNA assay in Ghana. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract 2017;4:5 10.1186/s40661-017-0041-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Segondy M, Kelly H, Magooa MP, et al. . Performance of careHPV for detecting high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia among women living with HIV-1 in Burkina Faso and South Africa: HARP study. Br J Cancer 2016;115:425–30. 10.1038/bjc.2016.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bansil P, Lim J, Byamugisha J, et al. . Performance of cervical cancer screening techniques in HIV-infected women in Uganda. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2015;19:215–9. 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lorenzi AT, Fregnani JH, Possati-Resende JC, et al. . Can the careHPV test performed in mobile units replace cytology for screening in rural and remote areas? Cancer Cytopathol 2016;124:581–8. 10.1002/cncy.21718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maza M, Alfaro K, Garai J, et al. . Cervical cancer prevention in El Salvador (CAPE)-An HPV testing-based demonstration project: changing the secondary prevention paradigm in a lower middle-income country. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2017;20:58–61. 10.1016/j.gore.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tshomo U, Franceschi S, Dorji D, et al. . Human papillomavirus infection in Bhutan at the moment of implementation of a national HPV vaccination programme. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:408 10.1186/1471-2334-14-408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Herrero R, et al. . Sexual behavior, condom use, and human papillomavirus: pooled analysis of the IARC human papillomavirus prevalence surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:326–33. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vaccarella S, Herrero R, Dai M, et al. . Reproductive factors, oral contraceptive use, and human papillomavirus infection: pooled analysis of the IARC HPV prevalence surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:2148–53. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hall CS, Fottrell E, Wilkinson S, et al. . Assessing the impact of mHealth interventions in low- and middle-income countries--what has been shown to work? Glob Health Action 2014;7:25606 10.3402/gha.v7.25606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Howitt P, Darzi A, Yang GZ, et al. . Technologies for global health. Lancet 2012;380:507–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61127-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016309supp001.pdf (115.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016309supp002.doc (85KB, doc)