Abstract

The unique property of phosphate-based glasses and fibres to be completely dissolved in aqueous media is largely dependent on the glass composition. This article focuses on investigating the effect of replacing Na2O with 3 and 5 mol% Fe2O3 on cytocompatibility, thermal and dissolution properties of P2O5–CaO–Na2O–MgO–B2O3 glass system, where P2O5 content was fixed at 45 mol%. The effect of increasing Fe2O3 from 3 to 5 mol% on P2O5–CaO–Na2O–MgO glasses was also evaluated. The glass transition temperature, onset of crystallisation temperature and liquidus temperature were found to decrease with increasing Fe2O3 content and the addition of B2O3, while the thermal expansion values were found to decrease. The density of the glasses decreased with increasing Fe2O3 content. However, an increase in the density was observed by the addition of 5 mol% B2O3. The dissolution properties and mode of bulk glass and fibres were also examined which were found to decrease with increasing B2O3 and Fe2O3. However, it was found that the dissolution properties of the glasses containing both B2O3 and Fe2O3 were lower than only Fe2O3 containing glasses. The in vitro cell culture studies using human osteoblast like (MG63) cell lines revealed that the glasses containing both B2O3 and Fe2O3 maintained and showed higher cell viability as compared to the only Fe2O3 containing glasses. Glasses containing both B2O3 and Fe2O3 showed a pronounced effect on the dissolution rate of the glasses, which eventually improved the cytocompatibility properties of the glasses investigated.

Keywords: Phosphate-based glasses, dissolution properties, thermal properties, fibre dissolution mode, cytocompatibility

Introduction

The properties of phosphate-based glasses (PBGs) such as glass transition temperature, thermal expansion coefficient, density, molar volume and dissolution rate strongly depend on the amount and type of modifying oxides added to the glass structure.1 Addition of metal cations with higher valency can potentially increase the cross-linking with the glass structure which can decrease the dissolution rate of the glass.2 Moreover, addition of cations with higher field strength can also decrease the dissolution rate via increasing the covalent character of the bonds within the glass structure.3 The dissolution rate of PBGs is also dependent on P2O5 content, although the effect is less significant as compared to that of metal cations.4 The ability of PBGs to tune the dissolution rate has prompted interest in using these glasses for different biomedical applications.5,6 One more unique property of PBGs is the ability of these glasses to be converted into fibres which could be used as a reinforcement of different bioresorbable polymers to produce totally bioresorbable composites for use in fracture fixation devices.7–10

A number of glass systems have been developed by addition of various metal oxides such as Fe2O3, Al2O3, ZnO, TiO2, B2O3 and SrO for hard tissue engineering applications. Effect of Fe2O3, CaO and MgO addition on the dissolution property of P2O5–Na2O binary glass systems has been reported by Parsons et al.11 and Shih et al.,12 where the glass dissolution rate was found to significantly reduce with increasing amount of modifying oxides. Generally, trivalent cation oxides such as iron (Fe3+), titanium (Ti3+) and boron (B3+) are found to show greater influence on the solubility of phosphate glasses as compared to the divalent (Ca2+, Mg2+) and monovalent cation oxides.13–17

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in using borophosphate glasses as potential biomaterials, particularly due to the significant effect of B2O3 addition on the fibre-drawing process and also on the mechanical properties of the fibres.1 This ease of fibre formation and higher mechanical properties was attributed to the extension of phosphate chain length and increased crosslinking.18 Moreover, addition of B2O3 has also proven to improve the thermal and dissolution properties of PBGs. However, addition of B2O3 to PBGs did not show any favourable effect on the cell culture behaviour.2 It has already been proven that the addition of Fe2O3 to PBGs significantly improve the cytocompatibility of these glasses. However, the Fe2O3 does not impart any favourable effect on the fibre-drawing process. Therefore, the initial aim of this study was to evaluate the combined effect of B2O3 and Fe2O3 addition on the dissolution rate and dissolution mode of PBGs and fibres. The final aim was to relate the dissolution behaviour of B2O3 and Fe2O3 containing glasses with the cytocompatibility behaviour in order to evaluate the viability of these glasses as potential biomaterials. The phosphate content was fixed to 45 mol%. The effect of B2O3 and Fe2O3 addition on the thermal properties and density of PBGs was also evaluated.

Materials and methodology

Materials

Table 1 lists the precursors used in this study for making glass. All the precursors were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, UK.

Table 1.

Name and chemical formula of the precursors added during glass manufacture.

| Name of the oxide required | Name and chemical formula of the precursor added |

|---|---|

| P2O5 | Phosphorous pentoxide (P2O5) |

| CaO | Calcium hydrogen phosphate (CaHPO4) |

| Na2O | Sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4) |

| MgO | Magnesium hydrogen phosphate trihydrate (MgHPO4.3H2O) |

| B2O3 | Boron oxide (B2O3) |

| Fe2O3 | Iron (ΙΙΙ)-phosphate dehydrate (FePO4.2H2O) |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) consisting of DMEM (Gibco Invitrogen, UK) and 0.85 mM of ascorbic acid (Sigma–Aldrich) was used for cell culture studies. The supplementary components contained in DMEM are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Name and concentration of the supplementary components present in Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) for cell culture studies.

| Supplementary component | Concentration in % |

|---|---|

| Foetal calf serum (FCS) | 10 |

| HEPES buffer | 2 |

| Penicillin/streptomycin | 2 |

| Glutamine | 1 |

| Non-essential amino acids | 1 |

Glass preparation

Melt-quenching process was used for the preparation of glass, where appropriate amount of precursors were mixed properly in a 200-mL volume Pt/5% Au crucible (Birmingham Metal Company, UK). The crucible containing the precursors was then moved to a furnace preheated to 350°C for half an hour for the removal of H2O, followed by melting in another furnace at 1150°C for 1.5 h. Finally, the molten glass was poured onto a steel plate and left to cool. As seen from Table 1, for all glass formulations, P2O5, CaO and MgO content were fixed to 45, 16 and 24 mol%, respectively, while the Fe2O3 content varied between 3 and 5 mol%. Two glass formulations contained 5 mol% B2O3 (coded as P45B5Fe3 (with 3 mol% Fe2O3) and P45B5F5 (with 5 mol% Fe2O3)), while other two did not contain any B2O3 (coded as P45Fe3 (with 3 mol% Fe2O3) and P45Fe5 (with 5 mol% Fe2O3)).

Thermal analysis

The thermal analysis of the glasses was conducted using a differential scanning calorimeter (TA Instruments SDT Q600, UK). The glass transition temperature (Tg), onset of crystallisation (Tons), peak crystallisation (Tc), melting (Tm) and liquidus (TL) temperatures of the glasses were identified from individual thermal scans. A rotating ball mill was used to ground the glasses into fine powder for the analysis. The powdered glass samples were heated from room temperature to 1100°C a rate of 20°C per minute under flowing argon gas. Each composition was repeated three times.

Thermo-mechanical analysis

In order to determine the thermal expansion coefficient (α) of the glasses, a 9-mm graphite mould was preheated to 450°C and the molten glass was transferred into it. The glass was kept at 450°C for 1 h, and the temperature of the furnace was allowed to cool down to room temperature. Afterwards, the glass rods were preheated again to a temperature of 10°C above the glass transition temperature of individual glass composition at a rate of 5°C per minute and then cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 20°C per minute to remove the residual stresses from the glass rods. The glass rods were then cut using a low-speed saw into 7-mm-thick discs. Ethanol was used as lubricating oil for the cutting procedure. The 9 mm × 7 mm glass samples were heated at a rate of 5°C per minute with an applied load of 50 mN using a thermo mechanical analyser (TMA Q400, UK). The measured thermal expansion coefficient (α) was taken as an average between 50°C and 250°C. The whole experiment was conducted in triplicates.

Density measurement

Micromeritics AccuPyc 1330 helium pycnometer (Norcross, GA, USA) was used to identify the effect of composition on the density of the glasses which was calibrated using a standard calibration ball (3.18551 cm3) with errors of ±0.05%. Bulk glass samples were used for the density measurements.

Fibre production

Dedicated in-house facilities were used to produce fibres with ~20 µm diameter via a melt-drawn system where molten glass was exuded from a bushing and collected on a rotating drum in the form of fibre. The diameter of the fibres could be adjusted via adjusting the temperature of the glass melt or the speed of the collection drum.

Dissolution studies

For dissolution studies of the glass samples, the previously casted 9-mm diameter glass rods were cut into 5-mm discs in the same process as described in the ‘Thermo-mechanical analysis’ section. The height and diameter of each discs were measured, and the discs were dipped in 30 mL of phosphate buffer solution (PBS) contained in glass vials. These vials containing the glass discs in PBS solution were then placed into an incubator. The study was conducted at 37°C for 60 days. At various time points, the glass discs were dried off the PBS solution, and the area and mass of the glass discs were measured. At each time point, the previous PBS solution was drained out and fresh PBS solution was added. The dissolution rate of the glass rods was determined by plotting mass loss per area against time. The slope of this graph gave the dissolution rate in kg·m−2·s−1.

For the dissolution study, the fibres were cut into an average length of 50 mm and approximately 300 mg were placed vertically into the middle of individual glass vials, each containing 30 mL of PBS solution. The dissolution studies of the glass fibres were also conducted for 60 days. For the dissolution study of fibres, only P45Fe3 and P45B5Fe3 fibres were used as it was difficult to produce enough P45B5Fe5 fibres due to the high viscosity of the glass at the maximum attainable temperature of the fibre-drawing tower.

Cell culture

The cytocompatibility of the glass samples studied in this study was evaluated using MG63 cell lines (human osteosarcoma). The media and ascorbic acid were cultured in 75 cm3 flasks at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. For cell culture studies, 9-mm-diameter glass rods were cut into 2-mm-thick glass discs and then sterilised using dry heat (190°C) for 15 min followed by washing with sterilised PBS for three times. Concentration of the cells that were seeded onto the disc sample surfaces was 36,000 cells/cm2. The cell culture study was conducted for 7 days, and during this study period, the glass discs seeded with the cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5 vol% CO2. The metabolic activity of the cells and the morphology of the cells cultured on the surface of the glass discs were conducted in the same way described in a previous publication.

Results

Thermal analysis

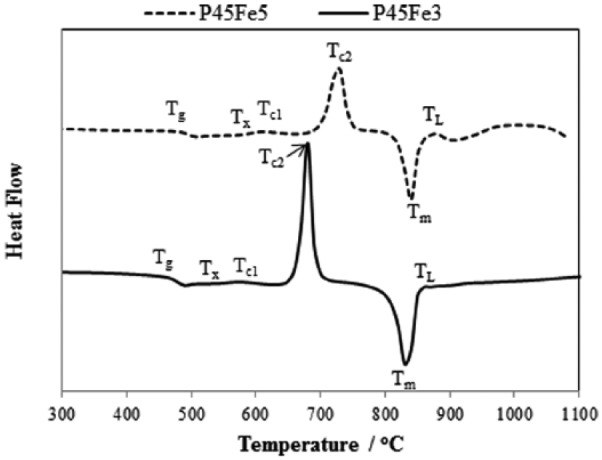

Thermal scans of glasses investigated in this study are shown in Figure 1 (P45Fe3 and P45Fe5) and Figure 2 (P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5). The corresponding glass transition temperature (Tg), onset of crystallisation (Tc,ons), crystallisation peak (Tc), melting peak (Tm) and liquidus (TL) temperature of the glasses have been reported in Table 3. As seen from Figure 1, Tg increased by ~32°C with increasing Fe2O3 content from 3 to 5 mol% for non-B2O3 containing glasses (P45Fe3 and P45Fe5). However, Tg only increased by ~11°C for 5 mol% B2O3 containing glasses as the Fe2O3 content increased from 3 to 5 mol% (P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5). Addition of 5 mol% B2O3 to the 3 and 5 mol% Fe2O3 containing glasses caused Tg to increase by ~30°C. Similar to glass transition temperature, the onset of crystallisation also increased with B2O3 addition in each glass system. Non-B2O3 exhibited two crystallisation peaks (labelled as Tc1 and Tc2), while the crystalline peaks were observed for 5 mol% B2O3 containing glasses (labelled as Tc1, Tc2 and Tc3). Moreover, P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glasses exhibited sharper second crystalline peaks as compared to P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses. One melting peak was observed for all the glass samples investigated and the melting temperature also shifted to higher temperature range with increasing B2O3 and Fe2O3.

Figure 1.

Thermal (DSC) scans for the P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glasses.

Figure 2.

Thermal (DSC) scans for the P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses.

Table 3.

Thermal characteristics (Tx, Tc, Tm and TL) for P45Fe3, P45Fe5, P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses.

| Glass batches (mol%) | Tg (°C) | Tc,ons (°C) | Tc (°C) | Tm (°C) | TL (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P45Fe3 | 470 ± 1.0 | 542 ± 0.5 | 578.3 ± 0.7 681.6 ± 0.4 |

834.8 ± 0.3 | 851.3 ± 3.0 |

| P45Fe5 | 485 ± 1.0 | 553 ± 1.0 | 604.6 ± 1.5 722.6 ± 0.3 |

838.6 ± 0.1 | 859.0 ± 0.1 |

| P45B5Fe3 | 502 ± 1.0 | 580 ± 1.0 | 623.4 ± 0.8 755.5 ± 0.8 845.0 ± 0.8 |

974.2 ± 0.8 | 1010.0 ± 0.3 |

| P45B5Fe5 | 513 ± 2.0 | 593 ± 1.0 | 631.0 ± 2.8 735.7 ± 2.7 857.0 ± 0.8 |

967.0 ± 1 | 1024.0 ± 0.3 |

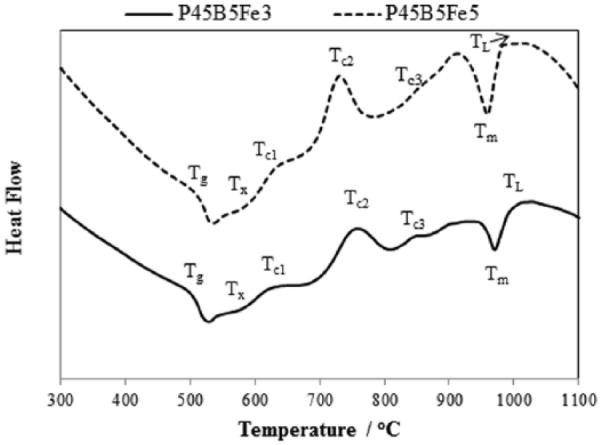

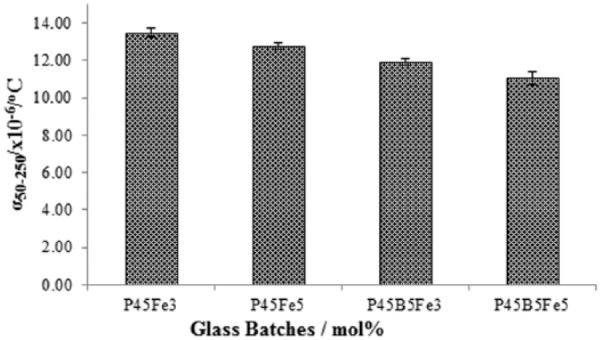

Thermal expansion

The glasses exhibited a decreasing trend in the thermal expansion coefficient values (denoted as α50–250) with increasing Fe2O3 and B2O3 content as shown in Figure 3. The thermal expansion coefficient values decrease from 13.48 × 10−6 °C to 12.76 × 10−6 °C as the Fe2O3 content increased from 3 to 5 mol%. A further decrease in thermal expansion coefficient from 11.92 × 10−6 °C to 11.03 × 10−6 °C was observed as 5 mol% B2O3 was added to the P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glass systems, respectively.

Figure 3.

Thermal expansion coefficient (α) of P45Fe3, P45fe5, P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses. Error bars represent the standard deviation where n = 3.

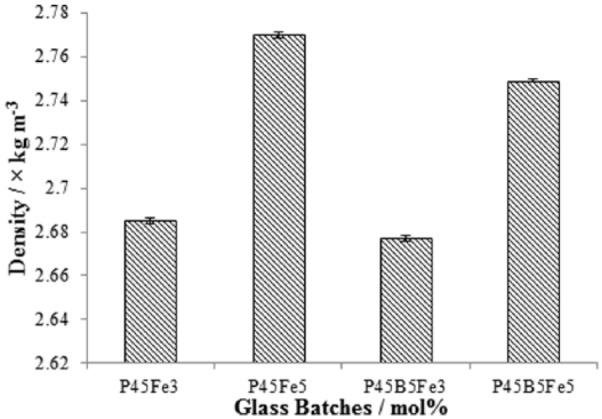

Density

Figure 4 shows the effect of Fe2O3 and B2O3 on the density of the glasses. The density was seen to increase with increasing Fe2O3 (3 to 5 mol%). The density of P45Fe3 was 2.68 × 103 kg. m−3, whilst the density increased to 2.77 × 103 kg. m−3 for P45Fe5 glasses. However, addition of B2O3 to glass systems was seen to decrease the density. The density of the P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glass systems decreased to 2.67 × 103 kg. m−3 and 2.74 × 103 kg. m−3, respectively as 5 mol% of B2O3 was added to the glass systems.

Figure 4.

Density (ρ) of P45Fe3, P45fe5, P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses. Error bars represent the standard deviation where n = 3.

Dissolution studies

Figure 5 represents the dissolution rates obtained for the glasses investigated. A significant reduction in the dissolution rate was observed as Na2O was replaced with B2O3. A reduction in the dissolution rate was also observed with increasing Fe2O3 content from 3 to 5 mol%. The average dissolution rate of P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glasses was 9.38 × 10−9 and 8.82 × 10−9 kg·m−2·s−1, respectively, after 60 days of immersion in PBS at 37°C. However, the dissolution rate of P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses was 7.92 × 10−9 and 7.4 × 10−9 kg·m−2·s−1, respectively, which is significantly lower than the dissolution rate of P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glasses as shown in Figure 5. Selected SEM images of the degraded P45Fe3 and P45B5Fe3 fibres are shown in Figure 6. As seen from the figure, both fibre types dissolved via the peeling of the outer layer. However, the dissolution mode of the fibres containing both B2O3 and Fe2O3 was less drastic as compared to the only Fe2O3 containing fibres.

Figure 5.

Dissolution rates obtained for P45Fe3, P45Fe5, P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses. Error bars represent the standard deviation where n = 3.

Figure 6.

SEM images of (a) P45Fe3 non-annealed and (b) P45B5Fe3 non-annealed degraded fibres in PBS at 37°C after 1, 14, 28 and 60 days of solution degradation.

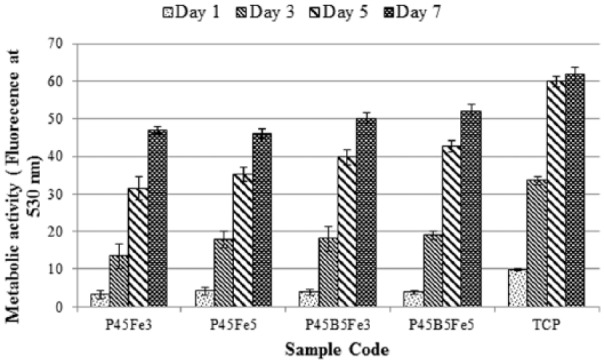

Cell culture

The Alamar Blue assay was used to determine the effect of B2O3 and Fe2O3 addition on the metabolic activity of osteoblast-like cells (MG63). The cells were cultured for 7 days as shown in Figure 7. The time points of the cell culture were Day 1, 3, 5 and 7. For all glass samples investigated, the metabolic activity was seen to increase throughout the entire cell culture period. The polystyrene (TCP) control demonstrated an elevated metabolic activity compared to the all other glass samples investigated. At Day 1, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the metabolic activity among the glass samples. At Day 5 and day 7, no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the metabolic activity among P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 was observed. However, the metabolic activity of P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glass samples was significantly higher than the P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glass samples at those two time points.

Figure 7.

Metabolic activity of MG63 cells, as measured by the Alamar Blue assay, cultured on PBGs. The time points are Day 1, 3, 5 and 7. Error bars represent the standard deviation where n = 3.

The SEM micrographs of MG63 cells cultured of P45Fe3, P45Fe5, P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glass samples after 7 days of cell culture are presented in Figure 8. As seen from the figure, a dense multi-layered cell matrix was observed on all glass samples investigated after 7 days of cell culture.

Figure 8.

SEM images of MG63 cells cultured on P45Fe3, P45Fe5, P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glass samples after 7 days of culture. Micrometer scale bar = 100 µm.

Discussion

The glass transition temperature (Tg) increased by ~15°C as the Fe2O3 content increased from 3 to 5 mol% in both the glass systems, one with 5 mol% B2O3 and one without any B2O3. Addition of network modifiers to these glasses can result in network strengthening of the glass which could eventually lead to an increase in thermal properties and durability.19 The replacement of P-O-P bonds with P-O-M bonds (where, M = modifier cation) can result in increased glass transition temperature. Moreover, increasing amount of modifier oxides to the glass structure could potentially increase the cross-link density between the phosphate chains.20 The increase in Tg is also strongly influenced by thee increasing field strength of the interstitial cations due to increased cross-linking.21 Thus, the increased Tg with increasing Fe2O3 as observed in this study could be attributed to the increased cross-link density between the phosphate chains due to the formation of P-O-Fe bonds.22 Tan et al.3 studied the effect of 5, 8 and 11 mol% Fe2O3 addition on the thermal properties of MgO and CaO containing borophosphate glasses and reported a ~5°C increase in the glass transition temperature with every 3 mol% increase in the Fe2O3 content. Day et al.23 suggested that the presence of sharper crystalline peak is an indication of lower resistance of the glass towards crystallisation as compared to the one with broader crystalline peak. As observed from Figures 2 and 3, glasses with lower Fe2O3 content (3 mol%) showed sharper crystalline peak. Therefore, it could be concluded that the increased amount of Fe2O3 did increase the resistance of the glasses towards crystallisation.

The Tg values increased by ~30°C with 5 mol% addition of B2O3 to the 3 mol% Fe2O3 (P45Fe3) and 5 mol% Fe2O3 (P45Fe5) containing glasses. A similar effect on increasing B2O3 on Tg was observed in a previous publication; the Tg values increased by 60°C and 120°C with 10 mol% B2O3 addition to the glass systems with P2O5 content fixed to 45 and 50 mol%, respectively.2 The Tg value of glasses containing 5 mol% B2O3 with P2O5 content fixed to 45 mol% was reported to be ~473°C.2 However, the Tg value of P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 observed in this study was 502°C and 513°C, respectively. Therefore, the Tg of glasses containing both B2O3 and Fe2O3 was higher than the glasses with B2O3 or Fe2O3 alone. This increase in Tg was attributed to the higher field strength of B3+ as compared to the Na+.2 Generally, the presence of several crystalline peaks indicates the presence of several crystalline phases within the glass system.15 As discussed above, the presence of broader crystalline peaks could be concluded as more resistance of the glass structure towards crystallisation. Therefore, the addition of B2O3 can potentially increase the resistance of the iron phosphate glasses towards crystallisation which can positively affect the biocompatibility of these glasses.

The thermal expansion coefficient (α) is a very good indicative of how the glass would behave under different thermal shock.24 The α50–250 values showed a decreasing trend with increasing Fe2O3 content (see Figure 3). The α50–250 values decreased by 7% as the Fe2O3 content increased from 3 to 5 mol%. A further decrease in the α50–250 values of P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glasses by ~15% was observed as 5 mol% B2O3 was added to the glasses. The α values of glasses are strongly influenced by the strength of glass network bonding, cross-linking and the interactions of the non-bridging oxygen with the cations.1,20 The network bonding and connectivity increases with the increasing cationic field strength, which is an indication of a cation’s effective force for attracting anions.25 The field strengths of both B3+ and Fe3+ cations are higher than Na+. Thus, because of the higher field strength, B3+ and Fe3+ would have a stronger ability to undergo coordination with other groups. Yu et al.26 investigated the effect of increasing Fe2O3 content from 14 to 43 mol% on the structure and properties of phosphate glasses and reported that the thermal expansion decreased with increasing Fe2O3. They suggested that reduction in thermal expansion coefficient with increasing Fe2O3 was an indication that the phosphorous–oxygen network became stronger due to the increased cross-linking between phosphate chains. Moreover, higher field strength–modifying oxides interacted strongly with the negatively charged phosphate anions and therefore hindered the mutual rotation and displacements of the anions which eventually decreased the thermal expansion. Thus, the increased cross-linking density with increasing Fe2O3 and B2O3 content decreased the basic structural vibrational movement of the glass, resulting in a decrease in the thermal expansion.

The density of the glasses is intensely affected by the field strength of the cations present in the glass structure. The presence of cations with higher field strength can form tighter bonding between phosphate chains as compared to the ones with lower field strength, which would eventually make the glass more compact and dense.25 In this study, B2O3 and Fe2O3 were added at the expense of Na2O. A monovalent cation (Na+) was replaced with trivalent cations (B3+ and Fe3+). Therefore, an increase in density was expected for both set of glasses. However, the density of the glasses only increased with increasing Fe2O3 (3 to 5 mol%; see Figure 4), and further addition of 5 mol% B2O3 decreased the density. The increase in density with increasing Fe2O3 could be associated with the higher field strength of iron as compared to sodium. Hasan et al.27 reported an increase in density with increasing iron content in the P2O5–CaO–MgO–Na2O–Fe2O3 glass system. They suggested that the density of the bulk glass was an important tool to measure the cross-link density and the packing structure of atoms, and the increased density with increasing Fe2O3 was due to the formation of Fe-O-P bonds and the structural changes associated with such change. Similar effect of increasing density with increasing Fe2O3 was also reported by Yu et al.26 The decrease in density of the glasses with B2O3 addition could be attributed to the increased chain length of the phosphate glass structure.18

The structure of pure PBGs without the presence of modifier oxides is composed of PO4 groups in chain/ring structures and many non-bridging oxygens.1,13 The -P-O-P- links present in the glass structure are known to hydrate easily and as such, P2O5 glasses, dissolve easily in aqueous media due to the fact that the 75% of the oxygen is bridging.23 Addition of modifying cations results in the partial depolymerisation of the glass network forming -P-O-M- (M/cation)-type links via the replacement of easily hydrated -P-O-P- bonds which consequently increase the chemical durability of the glasses. Addition of monovalent or divalent cations such as Na+ and Ca2+ can occupy ‘network modifying’ positions between the -P-O- chains, while multivalent cations such as B+ or Fe3+ may occupy ‘network forming’ positions by substituting a phosphorus ion in a -P-O-P- chain.2 Moreover, the addition of multivalent ions can create cross linking between the non-bridging oxygen of two phosphate chains which could also impart a positive effect on the durability of the glasses. As seen from Figure 5, the dissolution rate (by ~6%) was observed to decrease with increasing Fe2O3 (3 to 5 mol%) content. Fe can be present as Fe2+ and/or Fe3+ in the glass structure where Fe3+ can be present in both tetrahedral and octahedral coordination.28 Therefore, although Fe2+ acts as a network modifier, Fe3+ would act more like a network former, than a network modifier. Yu et al. studied the dissolution properties of sodium–iron phosphate glasses in water and also in saline at 90°C with iron content ranging from 14 to 43 mol% and with maximum Na2O content of 13 mol%. They reported that the increasing amount of Fe2O3 increased the durability of phosphate glasses both in water and in saline.28 Similar findings were also previously reported by Ahmed et al.15 and Hasan et al.27 Parsons et al.11 studied the effect of addition of different metal oxides on the dissolution rate of phosphate glasses and reported that the effect of different metal oxides goes in the order of Fe > Mg > Ca. Therefore, the decreased dissolution rate with increasing Fe2O3 was due to the replacement of P-O-P bonds with more hydration-resistant P-O-Fe bonds, and also due to the increased cross linking of the phosphate chains by iron ions.

A further reduction in the dissolution rate (~16%) was observed when 5 mol% B2O3 was added to the 3 mol% Fe2O3 (P45Fe3) and 5 mol% Fe2O3 (P45Fe5) containing glasses. As with Fe2O3 addition, the decrease in dissolution rate of the iron phosphate glasses with B2O3 addition was attributed to the replacement of P-O-P bonds with more hydration-resistant P-O-B bonds. Similar effect of B2O3 addition on the reduced dissolution rate of PBGs was reported in a previous publication.2 Kim et al.29 studied the dissolution property of borophosphate glasses in the system of xB2O3–(60–x)P2O5–40Na2O (x = 0, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mol%) and found that the dissolution rate of the glasses steeply decreased up to 30 mol% B2O3 addition. Ray et al.30 also suggested that the improvement in durability with the addition of boric oxide is related to the formation of durable BPO4 units. As mentioned in a previous publication, the dissolution rate of glasses with 5 mol% B2O5 and 45 mol% P2O5 with similar amount of CaO and MgO was 9.03 × 10−9 kg·m−2·s−1, whereas the dissolution rate of glasses containing both Fe2O3 and B2O3 is 7.92 × 10−9 kg·m−2·s−1 (for P45B5Fe3) and 7.40 × 10−9 k·gm−2·s−1 (P45B5Fe5), respectively. Therefore, addition of B2O3 together with Fe2O3 has more profound effect on the dissolution rate of the glasses than Fe2O3 or B2O3 alone.

Figure 8 shows the SEM images of P45Fe3 and P45B5Fe3 fibres degraded in PBS solution for 60 days. The P45Fe3 fibres went through more drastic degradation mode as compared to P45B5Fe3 glasses. The degradation of phosphate glass fibres usually takes place by peeling off the outer layer resulting in a decrease in the diameter of the fibres.31 In this study, we prepared ~20-µm-diameter fibres for the dissolution study. At the end of 60 days of dissolution study, the diameter of the P45B5Fe3 fibres reduced to ~15 µm, while for P45Fe3 fibres, the diameter of the degraded fibres went down to as low as ~8 µm. Therefore, the fibres containing both B2O3 and Fe2O3 were more resistant to hydrolytic attack, which is also consistent with the degradation studies conducted with the glass.

The SEM images of the MG63 cells cultured on the surface of the glasses investigated showed the presence of similar multi-layered dense cell layers after 7 days of cell culture. There was no significant difference in the metabolic activity between 3 and 5 mol% Fe2O3 containing glasses. However, the glasses containing Fe2O3 and B2O3 showed higher metabolic activity as compared to glasses containing Fe2O3 only. The biocompatibility of PBGs is strongly affected by the degradation rate. It is difficult for the cells to attach and proliferate on an unstable surface which might result from a high degradation rate.1 Moreover, lower degradation rate also helps to maintain the pH of the cell culture media suitable for cellular activity.32 It has already been well established that the addition of Fe2O3 could potentially enhance the biocompatibility of PBGs due to its positive effect on the chemical durability of these glasses.13,15,27 In a previous study, it was also reported that the addition of up to 5 mol% B2O3 into 45 and 50 mol% P2O5 containing glasses showed favourable cellular response.2 Zhu et al.33 studied the effect of increasing B2O3 content from 12 to 20 mol% on the cell metabolic activity and proliferation of PBGs. They suggested that the metabolic activity of the glasses containing 15 and 20 mol% B2O3 was significantly lower than the glasses with 12 mol% B2O3 due to the higher dissolution rate of the glasses. Fu et al.34 suggested that the accepted concentration level of boron in B2O3 containing bioactive glasses should be equal to or below 0.65 mM in order for them to be used as potential biomaterials. Therefore, from the cell culture studies, it could be concluded that the boron ion released from the glasses in this study did not impart any negative effect on the cytocompatibility of the glasses, rather the higher chemical durability of glasses with Fe2O3 and B2O3 made them more suitable for different biomedical applications.

Summary

In this article, Four PBG compositions were produced by replacing Na2O with B2O3 and/or Fe2O3 in the glass system P2O5–CaO–Na2O–MgO, and the P2O5 content was fixed at 45 mol%. It was not possible to determine the proportion of Fe2+or Fe3+ oxides in this study. Tg, Tc, TL and Tm increased as Na2O was replaced with B2O3 and/or Fe2O3. The highest Tg (513°C) was observed for glasses with 5 mol% Fe2O3 and/or FeO and 5 mol% B2O3 (P45B5Fe5). However, the thermal expansion coefficient values, density and dissolution glasses containing both B2O3 and Fe2O3 were significantly lower than the only B2O3 or Fe2O3 containing glasses. The improved physical properties of the glasses investigated with the addition of B2O3 and Fe2O3 were attributed to the replacement of P-O-P bonds with P-O-B and P-O-Fe bonds. The in vitro cell culture studies revealed that both P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses maintained and showed higher cell viability as compared to the P45Fe3 and P45Fe5 glasses. This was attributed to the slower dissolution rate of P45B5Fe3 and P45B5Fe5 glasses as compared to P45Fe3 and P45Fe5.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was financially supported by the NSFC Research Fund for International Young Scientists (Project Code: 51650110504).

References

- 1. Sharmin N, Rudd CD. Structure, thermal properties, dissolution behaviour and biomedical applications of phosphate glasses and fibres: a review. J Mater Sci 2017; 52(15): 8733–8760. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sharmin N, Hasan MS, Parsons AJ, et al. Effect of boron addition on the thermal, degradation, and cytocompatibility properties of phosphate-based glasses. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 902427-1–902427-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan C, Ahmed I, Parsons AJ, et al. Structural, thermal and dissolution properties of MgO- and CaO-containing borophosphate glasses: effect of Fe2O3 addition. J Mater Sci 2017; 52(12): 7489–7502. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brow RK. Review: the structure of simple phosphate glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids 2000; 263–264: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uo M, Mizuno M, Kuboki Y, et al. Properties and cytotoxicity of water soluble Na2O-CaO-P2O5 glasses. Biomaterials 1998; 19(24): 2277–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gough JE, Christian P, Scotchford CA, et al. Synthesis, degradation, and in vitro cell responses of sodium phosphate glasses for craniofacial bone repair. J Biomed Mater Res 2002; 59(3): 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahmed I, Jones IA, Parsons AJ, et al. Composites for bone repair: phosphate glass fibre reinforced PLA with varying fibre architecture. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2011; 22(8): 1825–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Han N, Ahmed I, Parsons AJ, et al. Influence of screw holes and gamma sterilization on properties of phosphate glass fiber-reinforced composite bone plates. J Biomater Appl 2013; 27(8): 990–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khan RA, Parsons AJ, Jones IA, et al. Degradation and interfacial properties of iron phosphate glass fiber-reinforced PCL-based composite for synthetic bone replacement materials. Polym-Plast Technol 2010; 49(12): 1265–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Felfel RM, Ahmed I, Parsons AJ, et al. Investigation of crystallinity, molecular weight change, and mechanical properties of PLA/PBG bioresorbable composites as bone fracture fixation plates. J Biomater Appl 2012; 26(7): 765–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parsons AJ, Burling LD, Scotchford CA, et al. Properties of sodium-based ternary phosphate glasses produced from readily available phosphate salts. J Non-Cryst Solids 2006; 352(50–51): 5309–5317. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shih PY, Yung SW, Chin TS. Thermal and corrosion behavior of P2O5-Na2O-CuO glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids 1998; 224(2): 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abou Neel EA, Ahmed I, Blaker JJ, et al. Effect of iron on the surface, degradation and ion release properties of phosphate-based glass fibres. Acta Biomater 2005; 1(5): 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abou Neel EA, Chrzanowski W, Knowles JC. Effect of increasing titanium dioxide content on bulk and surface properties of phosphate-based glasses. Acta Biomater 2008; 4(3): 523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ahmed IC, Lewis CA, Olsen MP, et al. Processing, characterisation and biocompatibility of iron-phosphate glass fibres for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2004; 25(16): 3223–3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brauer DS, Karpukhina N, Law RV, et al. Effect of TiO2 addition on structure, solubility and crystallisation of phosphate invert glasses for biomedical applications. J Non-Cryst Solids 2010; 356(44–49): 2626–2633. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmed I, Shaharuddin SS, Sharmin N, et al. Core/clad phosphate glass fibres containing iron and/or titanium. Biomed Glasses 2015; 1: 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharmin N, Hasan MS, Rudd CD, et al. Effect of boron oxide addition on the viscosity-temperature behaviour and structure of phosphate-based glasses. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2017; 105: 764–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donald IW, Metcalfe BL, Fong SK, et al. The influence of Fe2O3 and B2O3 additions on the thermal properties, crystallization kinetics and durability of a sodium aluminum phosphate glass. J Non-Cryst Solids 2006; 352(28–29): 2993–3001. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Binghama PA, Hand RJ, Hannant OM, et al. Effects of modifier additions on the thermal properties, chemical durability, oxidation state and structure of iron phosphate glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids 2009; 355: 1526–1538. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eisenberg A. Glass transitions in ionic polymers. Macromolecules 1971; 4(1): 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin ST, Krebs SL, Kadiyala S, et al. Development of bioabsorbable glass fibres. Biomaterials 1994; 15(13): 1057–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Day DE, Ray CS, Marasinghe K, et al. An alternative host matrix based on iron phosphate glasses for the vitrification of specialized waste forms. Rolla, MO: University of Missouri-Rolla, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joseph K, Asuvathraman R, Venkata Krishnan R, et al. Investigation of thermal expansion and specific heat of cesium loaded iron phosphate glasses. J Nucl Mater 2012; 429(1): 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shih PY, Chin TS. Preparation of lead-free phosphate glasses with low Tg and excellent chemical durability. J Mater Sci Lett 2001; 20(19): 1811–1813. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu X, Day DE, Long GJ, et al. Properties and structure of sodium-iron phosphate glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids 1997; 215: 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hasan MS, Ahmed I, Parsons AJ, et al. Material characterisation and cytocompatibility assessment of quinternary phosphate glasses. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2012; 23(10): 2531–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu X, Day DE, Long GJ, et al. Properties and structure of sodium-iron phosphate glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids 1997; 215(1): 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim NJ, Im SH, Kim DH, et al. Structure and properties of borophosphate glasses. Electron Mater Lett 2010; 6(3): 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ray NH, Plaisted RJ, Robinson WD. Oxide glasses of very low softening points – 4. Preparation and properties of ultraphosphate glasses containing boric oxide. Glass Technol 1976; 17(2): 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharmin N, Parsons AJ, Rudd CD, et al. Effect of boron oxide addition on fibre drawing, mechanical properties and dissolution behaviour of phosphate-based glass fibres with fixed 40, 45 and 50 mol% P2O5. J Biomater Appl 2014; 29(5): 639–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brauer DS, Rüssel C, Vogt S, et al. Degradable phosphate glass fiber reinforced polymer matrices: mechanical properties and cell response. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2007; 19(1): 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhu C, Ahmed I, Parsons AJ, et al. Structural, thermal, in vitro degradation and cytocompatibility properties of P2O5-B2O3-CaO-MgO-Na2O-Fe2O3 glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids 2017; 457: 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fu H, Fu Q, Zhou N, et al. In vitro evaluation of borate-based bioactive glass scaffolds prepared by a polymer foam replication method. Mater Sci Eng C 2009; 29(7): 2275–2281. [Google Scholar]