Summary

While staying in the White House over Christmas 1941, Churchill developed chest pain on trying to open a window in his bedroom. Sir Charles Wilson, his personal physician, diagnosed a ‘heart attack’ (myocardial infarction). Wilson, for political and personal reasons, decided not to inform his patient of the diagnosis or obtain assistance from US medical colleagues. On Churchill's return to London, Wilson sought a second opinion from Dr John Parkinson who did not support the diagnosis of coronary thrombosis (myocardial infarction) and reassured Churchill accordingly.

Keywords: Churchill, Parkinson, Wilson (Moran)

Introduction

On 7 December 1941, the Japanese attacked the US base at Pearl Harbour. Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941 and, by this declaration, the United States was brought into the war in Europe.1 Immediately following the Pearl Harbour attack, Churchill made plans to travel to Washington to meet President Roosevelt to review ‘the whole war plan’.1 The party included Lord Beaverbrook (Minister of Supply and member of the War Cabinet), Admiral Pound (First Sea Lord), Air Marshall Portal (Chief of the Air Staff), Field Marshall Dill (former Chief of the Imperial General Staff) and Sir Charles Wilson (Churchill's personal physician) for whom this was the first voyage on which he had accompanied Churchill.2 Churchill wrote,

To his unfailing care I probably owe my life. Although I could not persuade him to take my advice when he was ill, nor could he always count on my explicit obedience to all his instructions, we became devoted friends.2

Methods

Information regarding Churchill's illness was available from various sources. Foremost were Churchill himself2–4 and Wilson (Lord Moran from March 1943).5 Sir John Parkinson's family also gave permission to include details from his medical report on Churchill. Gilbert, Churchill's main biographer, added further clinical details1,6 and Churchill's staff provided contemporaneous notes: those of John Martin (Principal Private Secretary)7,8 and Commander ‘Tommy’ Thompson RN (aide-de-camp)9,10 were particularly helpful.

A voyage amid world war 2

The details of Churchill's journey to Washington are explained in considerable detail by Lavery.11 Churchill left London by night train on the evening of 12 December1 and reached Gourock, on the Clyde, on the morning of 13 December. He was then taken by boat to the Duke of York, sister ship of the Prince of Wales, which had been sunk off Malaysia three days earlier.1 The Atlantic crossing was so rough that passengers were confined below decks for much of the journey. Churchill self-medicated with Mothersill's Seasick Remedy (hyoscine, chlorobutanol, caffeine) twice on the first day.1

The Duke of York dropped anchor off Hampton Roads just after 16:00 on 22 December.11 Roosevelt originally intended that Churchill and party should transfer to a destroyer then steam up the Potomac to Washington, but time was too short because of delays incurred during the sea voyage. The Americans had therefore laid on a special train. However, Churchill was impatient to end his journey after nearly ten days at sea, and arrangements were then made to fly Churchill from Hampton Roads to Washington.3 Churchill landed at Washington National Airport where the President was waiting in his car. ‘I clasped his strong hand with comfort and pleasure’, wrote Churchill.3 The party, which included Wilson,12 soon reached the White House where they were ‘welcomed by Mrs Roosevelt, who thought of everything that could make our stay agreeable’.3

Accommodation at the White House

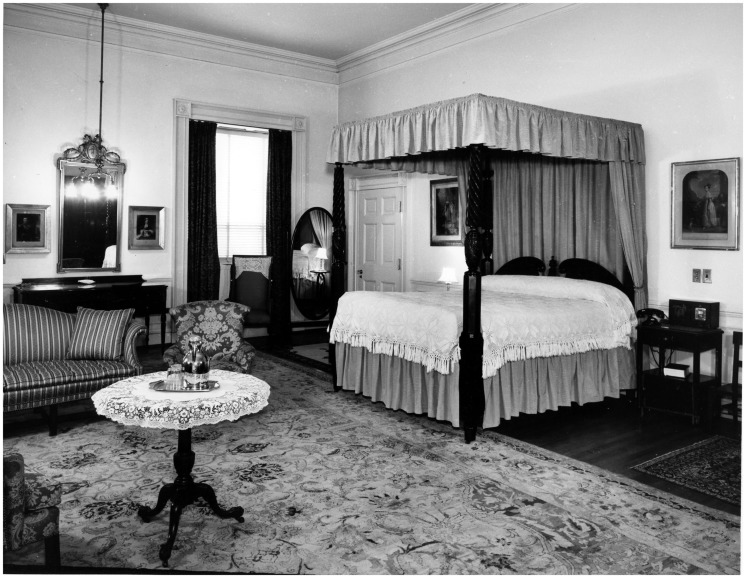

Mrs Roosevelt showed Churchill to the Lincoln bedroom, which he turned down, claiming that the bed did not suit him. He then looked over the others available. Alert as ever to opportunities, Churchill chose the Rose room on the second floor (also known as the Queens' room as this was where Queen Elizabeth slept on her 1939 visit with King George VI; Figure 1) across the hall from Harry Hopkins’ (Roosevelt's chief diplomatic adviser) almost permanent room.13

Figure 1.

Rose room (Queens’ room), White House. ©National Park Service, Abbie Rowe, Courtesy of Harry S. Truman Library.

22 December 1941

Dinner at the White House on 22 December was at 20:30 for 17 people. At its end, the President proposed a champagne toast to ‘The Common Cause’. After dinner, Churchill had a meeting with the President and conducted the two-hour conversation with great skill, according to Beaverbrook.5

At nearly midnight, Wilson received a message in his room at the Mayflower Hotel that Churchill wanted to see him5 and he set out for the White House in one of the President's cars. He waited in his patient's bedroom for an hour and a half before Churchill emerged from a meeting with President Roosevelt.5 Churchill apologised for keeping Wilson waiting, though Wilson surmised that Churchill had forgotten that he had sent for him.5 Wilson asked, ‘Is there anything wrong?’5 Churchill replied, ‘The pulse is regular.’5 As Lavelle14 later commented, ‘Churchill's immediate reference to his pulse could mean only that Churchill's pulse already had significance for both of them.’ Churchill asked if he could take a sleeping pill.5 Wilson agreed that he could take ‘two reds’ (quinalbarbitone 200 mg,15 a barbiturate hypnotic known also as secobarbital).

23 December 1941

At dinner, Percy Chubb (husband of a grandniece of the President), noted that while the President was ‘in a buoyant mood’, Churchill was ‘subdued and looked tired’12 as they discussed the Boer War. The President, a Boer sympathizer while at Harvard, ‘kept needling’ Churchill about being on the wrong side.12

Christmas Eve

‘Simple festivities marked our Christmas,’ wrote Churchill.3 The traditional Christmas tree was set up in the White House garden having been moved from Lafayette Park out of wartime caution. So, the President and he went on to the White House's South Portico balcony for the traditional ceremony of lighting the tree.13 After singing carols, both made brief speeches to crowds of some 20,000–30,000.3,5 Churchill's began, ‘I spend this anniversary and festival far from my own country, far from my family, yet I cannot truthfully say I feel far from home…’12 Wilson had been detained from attending the ceremony because Beaverbrook (also his patient) had a sore throat.14

After coming in from the balcony, Churchill told Wilson that he had had palpitations during the ceremony5 and made Wilson take his pulse.5 ‘What is it, Charles?’5 Wilson tried to be reassuring by saying, ‘Oh it's all right.’5 ‘But what is it?’ Churchill persisted.5 On being told it was 105 per minute, Churchill responded, ‘It has all been very moving.’5

Christmas Day

On Christmas morning, Churchill invited Wilson to go with him to Ottawa in a few days, adding that he was not afraid of being ill but that he ‘must keep fit for my job’.5

Churchill then went with the President to the Foundry Methodist Church on 16th and P Streets.

I found peace in the simple service and enjoyed singing the well-known hymns, and one, O little town of Bethlehem, I had never heard before. Certainly there was much to fortify the faith of all who believe in the moral governance of the universe.3

After sharing in the Roosevelt family celebrations, including the turkey dinner, which the President carved,16 Churchill spent a good part of Christmas Day preparing his speech to Congress.

26 December 1941

On 26 December, Wilson went to the White House to pay his daily visit to Churchill. Martin told him that the Prime Minister was still working on his speech to Congress, so he did not see him until later when he joined Churchill at the Capitol and heard the now-famous speech.

Churchill recalled that the President wished him good luck when he set out in the charge of the leaders of the Senate and House of Representatives from the White House to the Capitol. Churchill had never addressed a foreign parliament before, so it was with ‘heart-stirrings’ that he fulfilled the invitation to address the Congress of the United States. He felt a ‘blood-right to speak to the representatives of the great Republic’ as he could trace unbroken male descent on his mother's side through five generations from a lieutenant who served in George Washington's army.3

‘Inside the scene was impressive and formidable, and the great semicircular hall, visible to me through a grille of microphones, was thronged’3 (Figure 2). Churchill began,

I feel greatly honoured that you should have invited me to enter the United States Senate Chamber and address the representatives of both branches of Congress. The fact that my American forebears have for so many generations played their part in the life of the United States, and that here I am, an Englishman, welcomed in your midst, makes this experience one of the most moving and thrilling in my life, which is already long and has not been entirely uneventful. I wish indeed that my mother, whose memory I cherish across the vale of years, could have been here to see. By the way, I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way round, I might have got here on my own.12

Figure 2.

Churchill addresses a joint session of the US Congress on 26 December 1941 in Washington, DC. ©IWM (NYP 54898).

Churchill spoke for 35 minutes but was so impressive that one correspondent said it seemed like just five!17

27 December 1941

On 27 December, Wilson decided not to call upon Churchill as he seemed preoccupied. However, on returning to his hotel after a morning walk, he found an urgent message requesting he go at once to the White House. Wilson took a taxi and when he arrived, Churchill told him that he had got up in the night to open a window (Figure 1) as it was hot, but had to use considerable force to open it and became short of breath. ‘I had a dull pain over my heart. It went down my left arm. It didn't last very long, but it has never happened before. What is it?’5 Churchill indicated that he had thought of calling Wilson at the time but the pain had passed off. Wilson examined his patient but found nothing wrong.5

‘I had no doubt… his symptoms were those of coronary insufficiency,’ wrote Wilson later.5 Naturally, after Wilson had listened to his chest twice, Churchill enquired ‘Well, is my heart all right?’ Wilson replied, ‘There is nothing serious. You have been overdoing things.’ Churchill was adamant. ‘Now, Charles, you're not going to tell me to rest. I can't. I won't. No one else can do this job. I must.’ Churchill believed that he had strained one of his chest muscles when he tried to open the window. ‘I used great force. I don't believe it was my heart at all.’ Wilson explained to Churchill, ‘Your circulation was a bit sluggish. It is nothing serious. You needn't rest in the sense of lying up, but you mustn't do more than you can help in the way of exertion for a little while.’

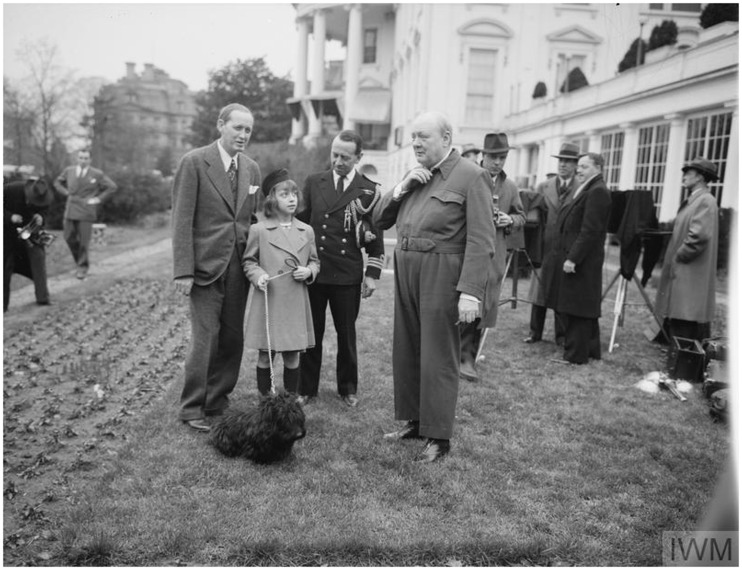

Then there was a knock at the door and Harry Hopkins (Figure 3) came in. Wilson slipped away and began to think things out more deliberately. ‘I did not like it, but I determined to tell no one. When we get back to England, I shall take him to Parkinson (Dr John Parkinson, Cardiologist), who will hold his tongue.’

Figure 3.

Churchill in his siren suit with Harry Hopkins and daughter, Diana, and Commander Thompson RN on the White House lawn. ©IWM.

Churchill himself wrote that this episode occurred on 3 January 1942.

The night before I started (for Florida) the air conditioning of my room in the White House failed temporarily, the heat became oppressive, and in trying to open the window, I strained my heart slightly, causing unpleasant sensations which continued for some days. Sir Charles Wilson, my medical adviser, however, decided that the journey south should not be put off.4

Irrespective of the date this pain occurred, Churchill carried on with his punishing schedule. This included seeing the President for several hours every day, lunching with him and often with Harry Hopkins as a third. ‘We talked of nothing but business, and reached a great measure of agreement on many points, both large and small.’3

28–31 December 1941, Ottawa

Churchill left Washington in Roosevelt's private railroad car for Ottawa on 28 December at 14:15.6 Churchill asked Wilson to accompany him to the station, and as they drove out of the grounds, opened the window of the car. He was short of breath.5 ‘There seems no air in this car.’5 Then Churchill put his hand on Wilson's knee saying ‘It is a great comfort to have you with me’; the second time he had used these words in four days.5

Churchill slept well on the train and reached Ottawa on the morning of 29 December and drove through streets banked with snow. After a hot bath, he ‘seemed his usual self’, Wilson noted. Churchill then lunched with the Canadian War Cabinet, and in the evening attended a reception and dinner at Government House. Spare moments were spent working on the speech he was to give to the Canadian Parliament. So far, Wilson had observed nothing untoward in his patient, though when they were alone, Churchill repeatedly asked Wilson to take his pulse. ‘Once, when I found him lifting something heavy, I did expostulate,’ wrote Wilson.5 At this Churchill remarked, ‘Now, Charles, you are making me the heart-minded. I shall soon think of nothing else. I couldn't do my work if I kept thinking of my heart.’5

The speech to the Canadian Parliament was delivered on 30 December, and on the morning of 31 December, Churchill gave a press conference at Government House before returning to Washington for further talks with Roosevelt. His train left Ottawa at 15:00 on 31 December, reaching Washington at noon on 1 January 1942.12

1–4 January 1942, Washington

On New Year’s Day, Roosevelt and Churchill sat together in George Washington's pew at Christ Church in Alexandria and sang The Battle Hymn of the Republic.17 That evening at the White House, Roosevelt, Churchill and the Soviet and Chinese envoys signed A Declaration by the United Nations, affirming that the Allies were fighting because they were convinced that ‘complete victory over their enemies is essential to defend life, liberty, independence, and religious freedom’.17

Churchill claimed his ‘American friends thought [he] was looking tired and ought to have a rest’4 and Edward Stettinius, Special Assistant to the President, placed his small villa ‘in a seaside solitude near Palm Beach at my disposal and on 4 January [Gilbert6 and Martin8 both state it was on the 5 January] I flew down there’.4

5–11 January 1942, Pompano, Florida

On 5 January, Churchill flew in General Marshall's plane from Washington to West Palm Beach Airport to stay in the bungalow at Pompano, Florida.8 During the flight, he and the General had some ‘very good talks’. They were accompanied by Wilson, Martin and Commander Thompson.8

Five days we passed in the Stettinius villa, lying about in the shade or the sun, bathing in the pleasant waves, in spite of the appearance on one occasion of quite a large shark. They said it was only a ground shark; but I was not wholly reassured. It is as bad to be eaten by a ground shark as by any other. So I stayed in the shallows from then on.4

Wilson noted that ‘the blue ocean is so warm that Winston basks half-submerged in the water like a hippopotamus in a swamp’.5

Although this was a time of much-needed relaxation, the work was considerable.6 Churchill dealt with papers flown down from Washington, sometimes twice daily, telephoned his private office and rewrote four papers on the future of the War in the light of the decisions made in Washington.6 On 10 January, Churchill lunched with Consuelo Balsan (former Duchess of Marlborough), whom he had known for 40 years and who remarked that he looked so well and that this was due to Wilson, who had given up everything to be his physician.14

11–14 January 1942, Washington

After five days at Pompano, the party returned to Washington by train on 10 January.8 Further meetings followed with Roosevelt and the combined Chiefs of Staff.

14–16 January 1942, Bermuda

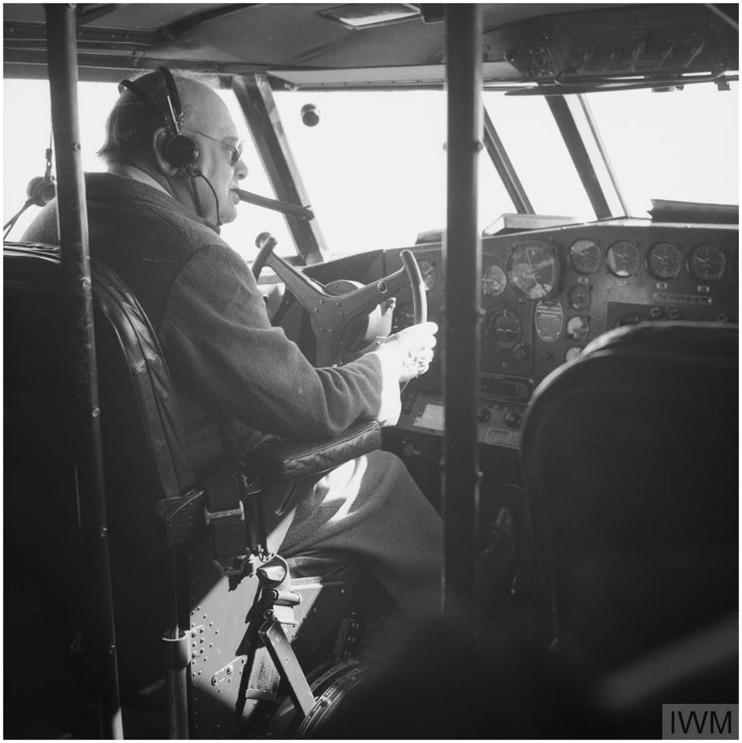

Churchill flew to Bermuda from Norfolk, Virginia, on 14 January and for 20 minutes of the four-hour flight took the controls of the Boeing 314 flying boat, RMA Berwick (Figure 4).6 The intent had been to return from Bermuda on the Duke of York but the worsening situation in Malaysia persuaded Churchill to fly to England. However, the entire party could not be fitted in and Churchill suggested to Wilson that he should return by sea. Wilson was appalled.5 Medically, he would be responsible if anything happened to Churchill in the air.5 Furthermore, as Wilson had been subjected to criticism for attending to Churchill while President of the Royal College of Physicians, he would be in difficulties if he returned to England a week or more after Churchill, for he had argued that looking after Churchill's health was even more important than doing his job as President.5 Wilson broke into a meeting of the Chiefs of Staff making plain that he could not agree.5 Whatever arguments he used were effective for he left with the Prime Minister and his immediate entourage in the flying boat.18 The 18-hour flight was uneventful medically, and shortly before 10:00 on 17 January, the aircraft set down at Plymouth.18

Figure 4.

Churchill at the controls of the Boeing 314 flying boat, RMA Berwick. ©IWM.

17 January–6 March 1942, London

Oliver Harvey (Private Secretary to Anthony Eden, Foreign Secretary) found Churchill in the ‘highest spirits and most truculent mood’ when he got back.19 On 9 February, Eden informed him in the greatest secrecy that Churchill was considering going to India the following week to meet Chiang Kai-shek and consult with Indian leaders about forming an assembly to work out a constitution for after the war19 and on his return, would stop in Cairo and ‘clear up the mess there’.19 Harvey advised Eden that while there were others (including Eden) who could take on some of these roles, only Churchill could do them all.19 The problem, Eden explained to Harvey, was that the doctors had told Churchill that ‘his heart is not too good and he needs rest’.19 Eden asked Churchill what he felt himself and he said he would go if the Cabinet wanted him to go but confessed that he did feel his heart a bit.19 He had tried to dance a little the other night but found that he ‘very quickly lost his breath’.19

On 6 March, Churchill told Eden that he was contemplating meeting with Stalin either in Teheran or in Russia. ‘This from a man afflicted with heart who may collapse at any minute. What courage and what gallantry, but is this the way to do things?’ Harvey wondered.19

Assessment by Dr John Parkinson

No doubt based on what Churchill himself had said, the understanding of Eden and other senior officials in the Foreign Office in February/early March 1942 was that Churchill was suffering from clinically significant heart disease. So what was the expert cardiological view?

Parkinson was first consulted by Wilson about Churchill on 6 February 1942. Wilson showed him two ECGs (7 January 1941 and 6 February 1942), which he interpreted as demonstrating a normal rate and rhythm with left axis deviation. Later that same day Churchill indulged in a jig after dinner and experienced some discomfort below the left breast and some shortness of breath.20 The next day he complained of some tenderness along the ribs in that region.

Parkinson examined Churchill with Wilson in attendance on 10 February 1942 and went through the symptoms he had experienced while in Washington? Churchill had developed a pain across his chest and thought he had strained a muscle. The feeling was still present the next day and he was somewhat short of breath, but well and about. After a day or two (this implies that Churchill was correct about the timing of the chest pain), Churchill flew to Florida and enjoyed some surf bathing though again noticing some shortness of breath. Parkinson also obtained the history that before the Atlantic passage home, Churchill had felt slight palpitation and that his pulse was 110/min before embarking and the same after one hour in the air. It was decided to proceed, and the pulse rate shortly fell to normal. Wilson told Parkinson he thought the tachycardia before the flight was psychological.

Parkinson found Churchill's pulse was 80/min, his blood pressure was 160/85 mmHg, the heart sounds were normal and there were no murmurs. His abdomen was normal to palpation. A further ECG undertaken by Parkinson showed left axis deviation with T3 inversion, which Parkinson considered normal given Churchill's build. Extrasystoles were also noted. Parkinson considered the new ECG was almost identical with the one recorded on 7 January 1941. On radioscopy, Churchill's heart and aorta were of normal shape and size. Parkinson told Churchill that he had not suffered a coronary thrombosis. There was no ECG evidence that anything material had occurred a month previously. There might have been a temporary embarrassment in the circulation of the heart in Washington, though there was no evidence to prove this. Churchill was advised to avoid extreme tests and long journeys in the next two to three months and even long walks on quays and inspections.

Churchill had a further episode of tenderness above the left breast on deep breathing while he was in bed on the night of 6 March and reported it to Parkinson on the 7 March when he examined him at Chequers and repeated the ECG. Parkinson told Churchill that the pain was muscular and had nothing to do with the heart. Churchill also reported extrasystoles, sometimes one in four, but accepted Parkinson's view that these were not of clinical significance.

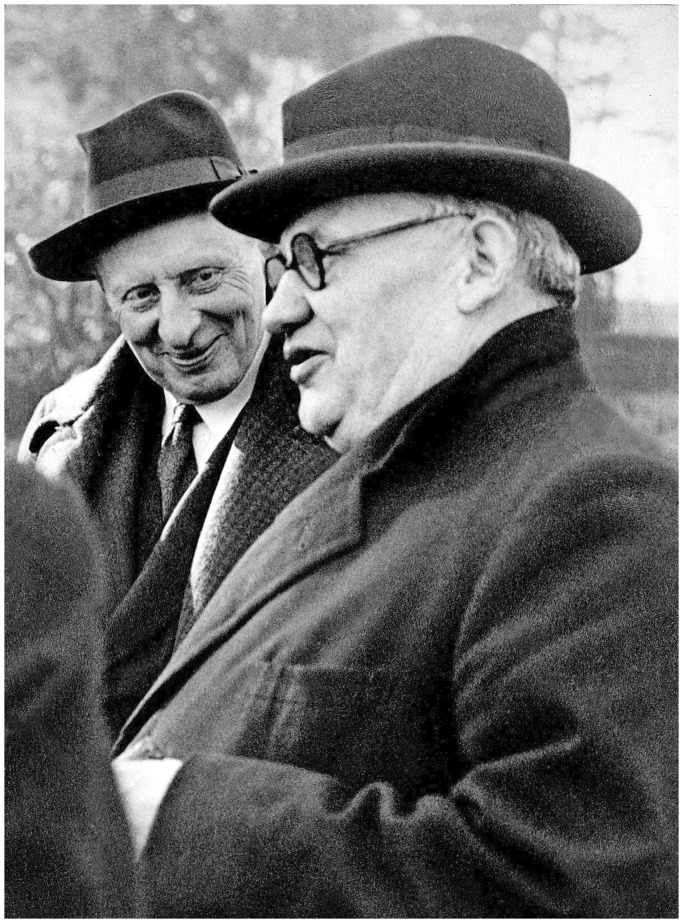

Churchill's doctors

Wilson (Figure 5) became Churchill's doctor on 24 May 1940 (two weeks into Churchill's first term as Prime Minister) and remained his personal physician until Churchill's death in 1965.21 He was appointed Dean of St Mary's Medical School in 1920, a post he held until 1945. He was knighted in 1938, created Baron Moran of Manton in the County of Wiltshire in 1943 and was President of the Royal College of Physicians of London from 1941 to 1950.21

Figure 5.

Sir Charles Wilson (left) with Ernest Bevin MP (Minister of Labour and National Service). Credit: A.P. Swaebe/Wellcome Library, London.

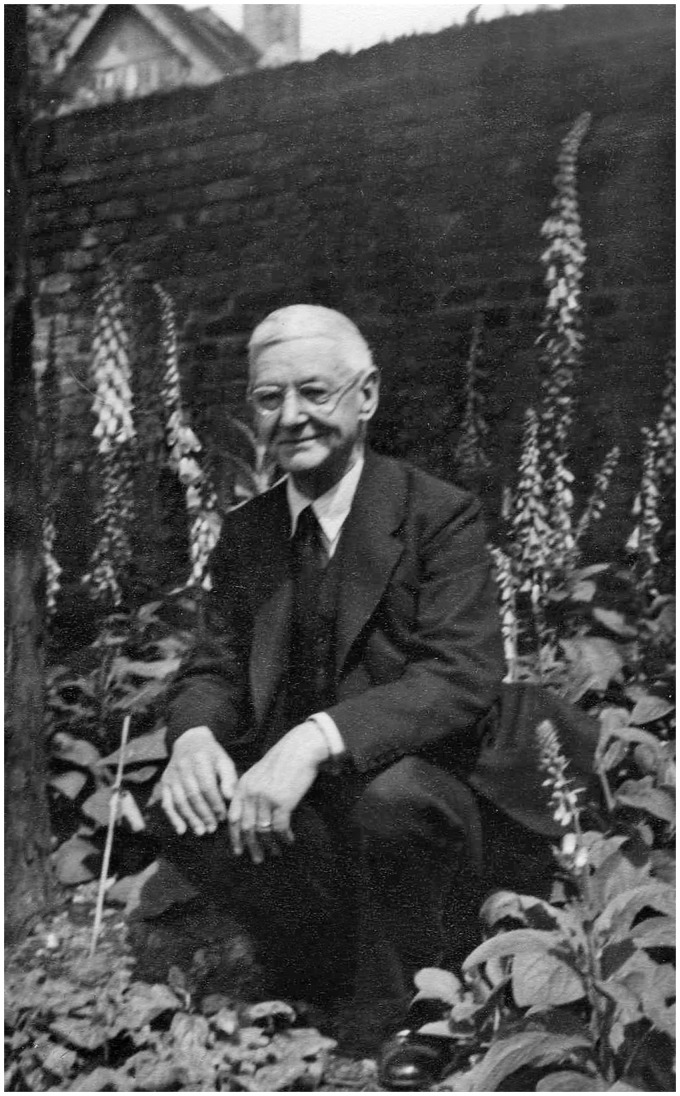

Parkinson (Figure 6) was appointed Assistant Physician to the London Hospital in 1920, Physician in 1927 and Physician to the Cardiac Department in 1933.22 He also became Physician to the National Heart Hospital, and from 1931 to 1956, was consulting cardiologist to the Royal Air Force.22 He was President of the Association of Physicians of Great Britain and Ireland and of the British Cardiac Society.22 Parkinson and Evan Bedford were foremost in correlating the symptoms and electrocardiographic signs of myocardial infarction (coronary thrombosis), especially identifying how they evolved in the weeks and months following the attack.23,24 In 1930, Parkinson along with Louis Wolff and Paul White in America described bundle-branch block associated with a short P-R period in healthy young people prone to paroxysmal tachycardia (the WPW syndrome).25 He was knighted in 1948.22

Figure 6.

Sir John Parkinson. ©Elva Carey.

Discussion

Churchill told Wilson that he had developed transient dull pain over (his) heart (the precise location was not stated by Wilson5) which went down his left arm, whereas Parkinson subsequently obtained the history from Churchill that he had developed a pain across his chest which persisted until the next day and was associated with some shortness of breath.

Did Wilson make the correct diagnosis? Although he did not document the precise location of the chest pain,5 the most obvious causes to be considered in a 67-year-old man are myocardial infarction, angina and musculoskeletal pain as Churchill himself favoured. Wilson had no doubt that Churchill's symptoms were due to a ‘heart attack’, a phrase he used twice.5 Although angina cannot be completely ruled out, the fact that Churchill never suffered a further attack is strongly against this diagnosis. Oesophageal spasm and gall bladder disease are also possible explanations, given Churchill's long history of dyspepsia. Churchill's indigestion, which was often severe, often came on during the night or when painting (‘I always paint standing up, otherwise the indigestion would be very severe’).26 Regardless of where in the chest the pain was experienced, and whether or not it went down the left arm, it came on as considerable effort was being expended and was associated with breathlessness. The latter, however, a later recurring feature, may only be the effect of exertion on the ‘hippopotamus’ that was Churchill.

Three weeks after Churchill's return to the UK, Wilson arranged for Parkinson to assess Churchill. After careful clinical, electrocardiographic and radiological assessment, Parkinson was firmly of the opinion that Churchill had not suffered a coronary thrombosis (myocardial infarction). Given that Parkinson had established with Evan Bedford the criteria for diagnosis,21,22 this opinion must be considered definitive. It is surprising that Wilson's published diary5 does not mention this opinion, particularly given that Wilson stated he would take Churchill to see Parkinson on his return from Washington.

So what may be said of Wilson's management? Obtaining an ECG in the White House would certainly have been difficult without drawing unwanted attention to Churchill’s health. Should he have sought the expert advice of a US-based cardiologist via the British Embassy or even had Parkinson flown out to Washington? Wilson was in a quandary. If he did nothing and Churchill had another and more severe attack, it might be said that he had killed Churchill through not insisting on rest.5 At least six weeks bed rest was standard treatment for myocardial infarction at the time. 5 ‘Right or wrong, it seemed plain that I must sit tight on what had happened, whatever the consequences.’5 To do otherwise would have meant ‘publishing to the world’ that Churchill was ‘an invalid with a crippled heart and a doubtful future’.5 The effect ‘could only be disastrous’. Wilson’s explanation to Churchill that his ‘circulation was a bit sluggish. It is nothing serious’ could be interpreted as being a less than full account of the episode but Wilson was certain that, if told what he did not doubt was the correct diagnosis, Churchill's ‘work would suffer’.5

Wilson considered that he had to balance political considerations, his own professional reputation and above all what was best for his patient who considered rightly that no one else but himself could fulfil his role as Prime Minister, duties which he must continue to undertake. Was he correct in doing so? Baron has written,

Moran took it on his own head to lie to Churchill about his heart attack in Washington because this diagnosis would have crippled Churchill and wrecked American esteem of Britain as an ally. Did this reason of state justify a physician concealing the truth from his patient and the public?27

Subsequently Baron wrote,

The many doctors who have written about the major illnesses of world leaders concurred that the public are entitled to full disclosure of candidates’ medical data. I agree. However, it is only fair to point out that …when I sought the opinions of senior London physicians in private practice of the great and the good they too held that doctors had a duty of confidentiality to their distinguished patients and no duty to the political health of their country.28

At a time of enormous importance in Anglo-American relationships and at a critical stage of the war, during which, in all respects, Churchill wished to be seen and act as a strong and effective leader, Wilson's decision to play the clinical importance down clearly carried some risk. It is obvious that Wilson agonised over this. ‘I felt that the effect of announcing that the PM had had a heart attack could only be disastrous’.5 But as well as recognising differences in clinical practice between the 1940s and the present era, we should remember that by this time, Churchill and Wilson had formed a trusting relationship (‘we became devoted friends’2) and a high level of understanding between each other.2

It seems likely that Churchill did indeed appreciate that Wilson had concluded that his symptoms were of cardiac origin. If Wilson's chronology is correct, Churchill’s remark to Wilson a few days later in Ottawa indicates Churchill’s recognition that focusing too much on his heart would detract from his ability to get on with his work. In the context of the unusually close relationship between the two men, Wilson’s approach may be interpreted as both shrewd and appropriate.

Conclusions

Churchill suffered an episode of chest pain while staying at the White House and without the benefit of an ECG or a second opinion, Wilson was of the opinion that Churchill had suffered a ‘heart attack’. For political and personal reasons, Wilson did not inform anyone else, including Churchill himself, of his diagnosis. On returning to London, Wilson sought a second opinion from Parkinson who did not support a diagnosis of myocardial infarction and reassured Churchill accordingly.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

AV

Contributorship

AV and JS wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to Mrs Elva Carey (daughter) and Dr John Phillips (grandson) for granting permission to include parts of Sir John Parkinson's medical report on Churchill, and also Lord Owen and Dr Alex Proudfoot for kindly providing advice.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by John Mather.

References

- 1.Gilbert M. Extraordinary changes. In: Road to Victory. London: Heinemann, 1986:1–22.

- 2.Churchill WS. A voyage amid world war. In: The Grand Alliance, (Vol. 3). London: Penguin Books, 1985:555–571.

- 3.Churchill WS. Washington and Ottawa. In: The Grand Alliance, (Vol. 3). London: Penguin Books, 1985:587–603.

- 4.Churchill WS. Anglo-American accords. In: The Grand Alliance, (Vol. 3). London: Penguin Books, 1985:604–618.

- 5.Moran. The new war. In: Winston Churchill. The Struggle for Survival 1940–1965. London: Constable & Company, 1966:5–23.

- 6.Gilbert M. Three weeks in the new world. In: Road to Victory. London: Heinemann, 1986:23–44.

- 7.Martin J. December 1943. In: Downing Street the War Years. London: Bloomsbury, 1991:124–133.

- 8.Martin J. January 1942. In: Downing Street the War Years. London: Bloomsbury, 1991:70–74.

- 9.Pawle G. Christmas at the White House. In: The War and Colonel Warden. London: George G. Harrap, 1963:142–154.

- 10.Pawle G. Interlude in Florida. In: The War and Colonel Warden. London: George G. Harrap, 1963:155–159.

- 11.Lavery B. The dull pounding of the great seas. In: Churchill Goes to War. London: Conway, 2007:67–87.

- 12.Gilbert M. December 1941. In: The Churchill Documents. The Ever-Widening War 1941, (Vol. 16). Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2011:1537–1718.

- 13.Kearns Goodwin D. Two little boys playing soldier. In: No Ordinary Time. New York: Touchstone, 1994:300–333.

- 14.Lovell R. 1941 – Moscow and Washington. In: Churchill's Doctor A Biography of Lord Moran. London: Royal Society of Medicine Services Ltd, 1992:157–175.

- 15.Lovell R. Lord Moran's prescriptions for Churchill. Br Med J 1995; 310: 1537–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin J. December 1941. In: Downing Street the War Years. London: Bloomsbury, 1991:66–69.

- 17.Meacham J. A couple of emperors. In: Franklin and Winston: A Portrait of a Friendship. London: Granta Publications, 2003:139–165.

- 18.Lavery B. A flying hotel in the fog. In: Churchill Goes to War. London: Conway, 2007:89–110.

- 19.Harvey O. 1942. In: Harvey J, ed. The War Diaries of Oliver Harvey 1941–1945. London: Williams Collins Sons, 1978:85–206.

- 20.Gilbert M. The fall of Singapore. In: Road to Victory. London: Heinemann, 1986:44–59.

- 21.Hunt TC. Charles McMoran Wilson, Baron Moran. Munk's Roll 1977; 7: 407.

- 22.Evans W. John (Sir) Parkinson. Munk's Roll 1976; 7: 443.

- 23.Parkinson J and Bedford DE. Successive changes in the electrocardiogram after cardiac infarction (coronary thrombosis). Heart 1928; 4: 195–239.

- 24.Parkinson J, Bedford DE. Cardiac infarction and coronary thrombosis. Lancet 1928; 211: 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff L, Parkinson J, White PD. Bundle-branch block with short P-R interval in healthy young people prone to paroxysmal tachycardia. Am Heart J 1930; 5: 685–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert M. Foreign affairs: towards France or Germany. Winston S. Churchill, (Vol. 5). London: Heinemann, 1976:781–793.

- 27.Baron JH. Should we know about our leaders' health? Standpoint, December 2009.

- 28.Baron JH. Churchill, Moran and the struggle for survival. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2011; 41: 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed]