Abstract

Research reports that perceived discrimination is positively associated with depressive symptoms. The literature is limited when examining this relationship among Black men. This meta-analysis systematically examines the current literature and investigates the relationship of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms among Black men residing in the United States. Using a random-effects model, study findings indicate a positive association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among Black men (r = .29). Several potential moderators were also examined in this study; however, there were no significant moderation effects detected. Recommendations and implications for future research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: depression, mental health, discrimination, meta-analysis, African American

Introduction

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability, leading to lost years of healthy life. It is expected to be the second leading cause of disease burden by 2020 (Lopez & Murray, 1998; World Health Organization, 2008, 2009). In 2000, the economic burden of depression in the United States due to medical expenses and lost productivity was approximately $83 billion (Greenberg et al., 2003). A 2013 working paper by Peng, Meyerhoefer, and Zuvekas (2013) specifically examined lost productivity costs and estimated that the aggregated annual productivity losses in 2009 as a result from depression-induced absenteeism (work impairment) ranged from $700 million to $1.4 billion. Peng et al. (2013) report that depression reduces the likelihood of employment and increases the number of annual work days lost among workers by approximately 33%. Effects of depression in the workforce is an arising problem that has been associated with higher rates of poor job performance, job turnover, underemployment (reduced hours and earnings), and unemployment (Lerner & Henke, 2008).

Despite its devastating social and individual impact, depression is one of the most common mental health disorders worldwide (American Psychological Association, 2014; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). A national study conducted by the CDC in 2008 estimated that approximately 9% of the adult U.S. population reported experiencing symptoms of current depression (CDC, 2010). Compared to non-Hispanic White Americans, Black Americans report higher levels of depressive symptoms, with prevalence rates of approximately 8% and 13%, respectively (CDC, 2010). Research suggests that Blacks residing in the United States may be experiencing greater severity of depression than other racial or ethnic groups. African Americans have been identified to be more likely to report a greater disability secondary to major depressive disorder and more chronic and severe major depressive disorder than Whites and Black Caribbeans (D. R. Williams et al., 2007). Together, these findings suggest that depressive disorders represent a particularly pressing problem to understand and address among Black Americans.

Several studies have linked depressive symptoms and other adverse mental health outcomes to experiences of discrimination (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2012). Specifically, research suggests that perceived discrimination, a psychosocial stressor, is a significant risk factor for the onset of depression among Blacks (Pieterse et al., 2012; Schulz, Gravlee, Williams, Israel, & Rowe, 2006; D. R. Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). Discrimination can be defined as unfair/unjust treatment based on one or more personal characteristics (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, social class, religion, age, weight, etc.; Thoits, 2010). Compared to other racial/ethnic groups, studies suggest that Blacks tend to report more discrimination based on race (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999; Pieterse et al., 2012). Research findings suggest that Black men report experiencing higher levels of discrimination than women, which also may contribute to some of the poorer health outcomes noted in men compared to women (Forman, Williams, & Jackson, 1997; D. R. Williams, 2003; D. R. Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003).

Although the depression phenomenon is well studied and well documented, there is a paucity of literature that examines depression in Black men. In fact, a prior review of the literature on depression risk factors among Black men identified only 17 articles that explicitly examined potential risk factors of depression in this population (Watkins, Green, Rivers, & Rowell, 2006). Articles selected for inclusion in Watkins et al.’s (2006) review were published between 1980 and 2004, with the majority published prior to 2000. More recently, Ward and Mengesha (2013) conducted a review of the literature that identified prevalence, risk factors, and both treatment-seeking behavior and barriers of depression among Black men. Over a 25-year time span, Ward and Mengesha identified only 19 empirical studies that focused on depression in Black men. Findings suggested that prevalence of depression among Black males ranged from approximately 5% to 10%. Ward and Mengesha further reported that Black men experience a number of risk factors such as demographics (i.e., ethnicity and gender), socioeconomic status (e.g., income, education, employment, poverty status), medical physical health problems (e.g., hypertension, circulatory problems), and psychological health (e.g., perceived stress, self-concept). The findings reported in Ward and Mengesha’s study further supported the findings of Watkins et al.’s (2006) literature review examining depression among Black men.

While these reviews contributed importantly to the literature by identifying potential factors leading to depression among Black men, neither empirically examined the magnitude and direction of the effect of perceived discrimination on depression among Black men. Several studies have identified the magnitude and direction of the effect of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms within single data sets (Bogart et al., 2011; Borrell, Kiefe, Williams, Diez-Roux, & Gordon-Larsen, 2006 ; Hammond, 2012; Utsey & Payne, 2000; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011); however, there have been no studies that have conducted a meta-analysis to calculate an aggregated effect size of the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among Black men.

Black men face a disproportionately high burden of prevalence and premature morbidity and mortality rates from injuries, illnesses, and chronic and stress-related conditions with high depression comorbidities (especially cancer, cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and homicide; American Cancer Society, 2009; CDC, 2013; Rich, 2000; Rosamond et al., 2008). Black men also face more exposure to adverse social and economic environments (e.g., discrimination, unemployment, poverty, violence, etc.) that generate or aggravate psychological distress (Center for Mental Health Services, 2001; Rich, 2000; D. R. Williams, 2003). This confluence of risk factors may contribute to outcomes typically linked to depression, including the steady rise in suicide rates reported among Black men and boys over the past several decades. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, between 1950 and 2004, the age-adjusted suicide rate for Blacks of all ages increased by approximately 28%, while it decreased by approximately 14% for Whites (National Center for Health Statistics, 2006).

Illness occurs when an individual’s ability to appropriately respond to stress is compromised and overcome by stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Stressors can be defined as “threat, demands, or structural constraints that . . . call into question the operating integrity of the organism” (Wheaton, 1999, p. 177). Perceived discrimination acts as a psychosocial stressor that significantly affects both the mental and physical health outcomes of racial/ethnic groups (Gee, Spencer, Chen, & Takeuchi, 2007; D. R. Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). Theory suggests that stress associated with experiences of discrimination, particularly racial discrimination, influences both psychological resources and social status of an individual (Clark et al., 1999; Harrell, 2000). More specifically, while grand experiences of racial discrimination might be easily recognizable as stressors, chronic, low-level daily experiences of invalidation classified by some as “racial micro-aggressions” (e.g., Franklin & Boyd-Franklin, 2000; Pierce, 1974) may pose the greatest threats to well-being. This may be because these experiences are not overt but frequent, often unpredictable, and typically brief. These “racial micro-aggression” experiences are invalidations that can generate anxiety, can lead to anger that is hard to target, may undermine self-confidence, can create negative expectancies (D. R. Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000), and may even internalize stereotypes or “psychological invisibility” (Franklin & Boyd-Franklin, 2000). Chronic stressors of this sort heighten a sense of vulnerability, prompt vigilance for the protection of self-worth, and ultimately pose the greatest risk for psychological health due to stress because of the constant drain on coping resources and identity (Harrell, 2000). Chronic stressors of this sort may also cause physical health effects, directly from injuries, as well as from allostatic load (Cohen, 1980; McEwen, 1998). Discrimination has been associated with health issues such as increased bed days and both substance abuse and unhealthy sleep patterns that may be associated with a variety of health issues such as unintentional injuries (Borrell et al., 2007; Steffen & Bowden, 2006; D. R. Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997).

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated and identified a significant positive relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms among a variety of racial and ethnic groups (Lee & Ahn, 2011; Paradies, 2006; Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Pieterse et al., 2012; D. R. Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Only one has focused specifically on Black Americans. Pieterse et al. (2012) conducted a meta-analytic review of studies of the relationship between racial discrimination and several constructs of mental health, including depression, anxiety, and general distress. Pieterse et al.’s study focused on the association among Black American adults across gender and identified a significant positive relationship. Examining correlations across studies, Pieterse et al. reported an aggregated correlation between perceived racial discrimination and psychological distress of .20 (95% confidence interval [CI; .17, .22]). Based on this report, racial discrimination negatively influences mental health among Black Americans.

Pieterse et al. (2012) examined a variety of potential moderators (racism scale used, measurement precision, sample type, publication type, and psychological outcomes) to investigate potential heterogeneity among studies. Of these five moderators examined in Pieterse et al.’s study, only psychological outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety) were identified as having a significant moderation effect, which suggests that some of the heterogeneity reported among the studies may have been explained by the different mental health outcomes examined. Although the study did report an overall significant relationship between discrimination and psychological outcomes, the authors did not specifically examine whether the effects differed by gender. With the disproportionate burden of morbidity and mortality rates, the high negative social and environment exposures, and the increase in suicide rates among Black men, a more systematic statistical assessment of the literature on the relationship between perceived discrimination and depression based on gender is needed. A statistical assessment that encompasses the magnitude, direction, and potential mechanism has great potential to add clarity and further direction to the current well-being and health discussions of Black men.

To the authors’ knowledge, no meta-analysis on the relationship between depressive symptoms and discrimination among Black American men has been conducted. Extending previous investigations, the purpose of the current study is to explore more specifically the relationship between perceived discrimination and depression/depressive symptoms among Black men. This investigation will describe and analyze the current state of the discrimination–depression literature associated with Black men residing in the United States to examine the magnitude and direction of this relationship.

Method

Study Selection

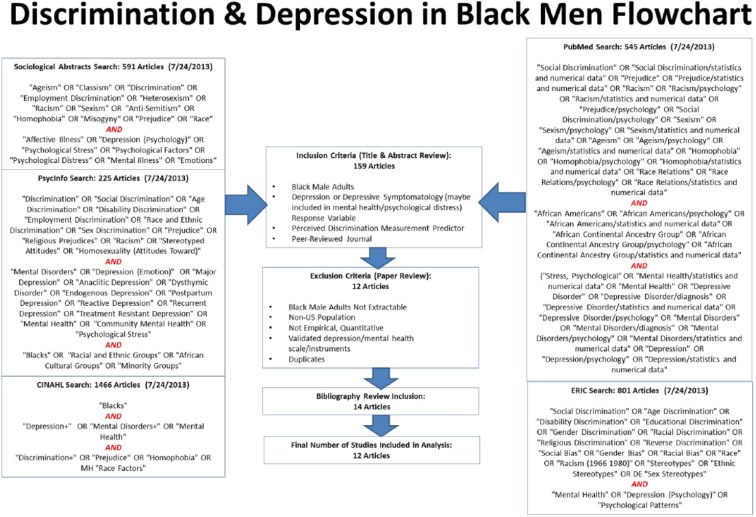

A comprehensive search of the PubMed, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL, ERIC, and PsycINFO databases was conducted to identify potential articles for this meta-analysis in July 2013. Inclusion criteria for this review required studies to (a) include results for Black male adults living in the United States at the time of study participation, (b) include a direct measure of depression and/or depressive symptoms as an outcome variable, (c) include a direct measure of self-reported perceived or experienced discrimination as an exposure, (d) address perceived discrimination as a primary predictor of depression and/or depressive symptoms, (e) be published in a peer-reviewed journal, and (f) include a correlation coefficient or have provided adequate information to compute a correlation coefficient for the depressive symptoms and discrimination variables among the Black men sampled in the study. Articles included studies on depression, depressive symptoms, and psychological distress/factors. Discrimination-related keywords including those that encompassed the general concept of discrimination and/or unfair treatment, as well as articles that specifically addressed discrimination in terms of race, class, sexual orientation, sex/gender, age, disability, education, and religion were also included in this study.

Exclusion criteria included the following: (a) studies that used non–U.S.-based populations, (b) studies that did not use validated depression/depressive symptomatology scales, (c) studies that did not provide quantitative results of the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms, (d) systematic reviews, and (e) studies for which results for Black men could not be clearly identified and extracted. Studies that sampled both Black men and women were included in the analyses only if they reported results separately for men or if an interaction term was tested between discrimination and depressive symptoms for gender and reported nonsignificant. Key search terms included general discrimination-relevant constructs (e.g., discrimination, prejudice) and specific types of discrimination (e.g., racial discrimination, racism, ageism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, homophobia) coupled with terms associated with depression (e.g., depression, psychological stress, mental disorders) and Blacks (e.g., African Americans, Blacks, racial and ethnic groups, minority groups). Exact search and Boolean terms used to identify potential articles in each database are reported in Figure 1. In addition, bibliographies of prior systematic reviews on depression and discrimination and articles selected for inclusion in this study were reviewed for other potential sources, which were acquired and checked against both the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of meta-analysis study search strategy.

Two reviewers in four separate rounds extracted studies selected for the current meta-analysis. For each round, the first and second reviewers independently examined in sequence the title (Round 1), abstract (Round 2), and main text (Round 3) of each article. Reviewers met after each round examination to determine which articles to include in the next round. Studies that were unclear on either of the inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis, but not clearly excluded, were retained for the next round. In the final round (Round 4) all potential articles were reviewed with a third reviewer to determine final inclusion. The process identified 159 articles for potential inclusion into the study. Of these 159 articles, 147 were removed from further consideration based on the exclusion criteria. Reviewing the bibliographies of the 12 studies selected for inclusion as well as 5 prior literature reviews identified, 2 additional articles were added to the collection of included studies. In total, 14 articles were selected for inclusion in the final study.

Analytic Plan

The analyses conducted used the Pearson product–moment correlation (r) as the effect size measure and the study as the unit of analysis; the sample size for each study contributed to the combined effect size only once, consistent with independence assumptions. Seven eligible studies reported more than one correlation coefficient due to different sample stratifications (e.g., age, coping styles, class) and several subscales within the discrimination instrument (e.g., Multiple Discrimination Scale, Index of Race-Related Stress–Brief Version) used. These correlations were averaged to create one effect size for each study. Three, out of the 14, otherwise eligible studies did not report sufficient statistical information that could be converted into correlation coefficients. Authors of these three studies were contacted directly to acquire this information. Only one of these three authors responded, and that study was included in the analyses. As a result, 12 studies were included in the final analysis for this report (Table 1).

Table 1.

Meta-Analysis Study Inclusion Summary Table.

| Author (year), journal | Depressive symptomatology instrument | Perceived discrimination instrument | Study type (comparison group), data source/sample | Analytic stratification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks, Kohn-Wood, and Spencer (2006), Community Mental Health Journal | Depressive symptoms; 3-item Depression Scale (Kessler et al., 2002) | Perceived everyday discrimination; 9-item Perceived Everyday Discrimination Scale (D. R. Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997) | Cross-sectional; 1995 DAS; 570 Black adult respondents, 180 male, 390 female; 18 years or older | Sample: other; Racism: frequency; Assessment: depression-related |

| Bogart et al. (2011), Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology | Depression symptoms; 8-item Medical Outcome Study’s Brief Depression Screener (Wells, Sturm, Sherbourne, & Meredith, 1996) | Perceived discrimination; 30-item MDS (3 subscales: MDS-Black, MDS-Gay, MDS-HIV; Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, & Banks, 2010) | Cross-sectional; HIV social service agencies and HIV medical clinic in Los Angeles, California; 181 HIV-positive adult African American/Black men; 18 years and older | Sample: other; Racism: appraisal; Assessment: depression-related |

| Bynum, Best, Barnes, and Thomoseo Burton (2008), Journal of African American Studies | Depressive symptoms; 7-item Depression subscale of the BSI (Derogatis & Meisarotis, 1983) | Perceived racist experiences; 9-item RaLES-Revised (Harrell, 1997a, 1997b) | Cross-sectional; Southeastern historically Black college/university and Midwestern predominantly White university; 107 Black male freshmen college students; 18 to 19 years old | Sample: college; Racism: appraisal; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Caldwell, Antonakos, Tsuchiya, Assari, and De Loney (2013), Psychology of Men & Masculinity | Depressive symptoms; 12-item CES-D Scale (Radloff, 1977; Roberts & Sobhan, 1992) | Perceived everyday discrimination; 10-item Perceived Everyday Discrimination Scale (D. R. Williams et al., 1997) | Cross-sectional; father and sons project (Midwest); 332 African American fathers; 22 years and older | Sample: other; Racism: frequency; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Greer, Laseter, and Asiamah (2009), Psychology of Women Quarterly | Depressive symptoms; 11-item Depression subscale of HScL-58 (Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Ulenhuth, & Covi, 1974) | Perceived race-related stress; 22-item IRRS-B (Utsey, 1999) | Cross-sectional; midsized southeastern predominantly White University; 183 African American adult college students; 62 men, 121 women; 18 years and older | Sample: college; Racism: appraisal; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Lightsey and Barnes (2007), Journal of Black Psychology | Depressive symptoms; 11-item Depression subscale of HScL-58 (Derogatis, 1974) | Perceived racial experiences; 2-item racial discrimination past experiences (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999) | Cross-sectional; Southern community college and moderate size southern university; 209 African American adult college students; 58 men, 195 women;18 years and older | Sample: college; Racism: appraisal; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Matthews, Hammond, Nuru-Jeter, Cole-Lewis, and Melvin (2013), Psychology of Men & Masculinity | Depressive symptoms; 12-item CES-D Scale (Radloff, 1977) | Perceived racist experiences; 18-item DLE-R from the RaLES (Harrell, 1997b) | Cross-sectional; west and south region barbershops and academic institutions; 458 African American men; 18 years and older | Sample: other; Racism: frequency; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Pieterse and Carter (2007), Journal of Counseling Psychology | Psychological distress (depressive symptoms); psychological distress subscale for the 38-item MHI (Veit & Ware, 1983) | Perceived racist experiences; 18-item SRE (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996) | Cross-sectional; barbershops in New York and Washington, D.C., and a university located in New York; 220 Black American men; 18 years and older | Sample: other; Racism: combined; Assessment: depression-related |

| Utsey and Hook (2007), Journal of African American Men | Psychological distress; 18-item BSI–Global Severity index (Derogatis, 2000) | Perceived race-related stress; 22-item IRRS-B (Utsey, 1999) | Cross-sectional; southeastern urban public university; 215 African American undergraduates; 83 men, 132 women; 18 to 35 years | Sample: college; Racism: appraisal; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Utsey and Payne (2000), Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology | Depressive symptoms; 21-item BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) | Perceived race-related stress; 22-item IRRS-B (Utsey, 1999) | Cross-sectional; northeastern substance abuse treatment program, northeastern medium-sized Catholic university, Southeastern historically Black University, and the community; 126 African American men (clinical vs. normal); 17 years and older | Sample: other; Racism: appraisal; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Watkins et al. (2011), Research on Social Work Practice | Depressive symptoms; 12-item CES-D Scale (Radloff, 1977; Roberts & Sobhan, 1992) | Everyday (racial) discrimination; 10-item perceived discrimination measure (D. R. Williams et al., 1997) | Cross-sectional; NSAL; 1,271 African American men; 18 years and older | Sample: other; Racism: frequency; Assessment: depression-specific |

| Zamboni and Crawford (2007), Archives of Sexual Behavior | Psychiatric symptoms; Global Severity Index of the 90-item Symptom Checklist–90 Revised (Derogatis, 1993) | Perceived racist experiences; 18-item SRE (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996) | Cross-sectional; Chicago, Illinois, Richmond, and Virginia; 174 African American gay and bisexual men; 18 years and older | Sample: other; Racism: combined; Assessment: depression-related |

Note. DAS = Detroit Area Study; MDS = Multiple Discrimination Scale; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; RaLES = Racism and Life Experiences Scales; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Study–Depression; HScL-58 = Hopkins Symptom Checklist–58; MHI = Mental Health Inventory; IRRS-B = Index of Race-Related Stress–Brief version; DLES = Daily Life Experience of Racism Scale; SRE = Schedule of Racist Events; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory–II; NSAL = National Survey of American Life.

Because correlation coefficients are not normally distributed, correlation effect sizes were assessed using the Fisher’s r to z transformation prior to aggregating effect sizes across studies. All estimates (means and 95% CIs) were computed into Fisher’s z for analysis and transformed back to the r metric for interpretation and reporting, as described by Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, and Rothstein (2009). The first step was to determine an overall pooled-effect estimate of the relationship of discrimination on depression in Black men. An overall effect size analysis was calculated with the STATA 12.0 metan function using the random option to conduct a random-effects method analyses. In addition, the metan function also was used to compute the Cochran’s Q statistic, which assesses for potential systematic differences in effect sizes between the studies (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). A significant Q statistic would suggest that heterogeneity does exist among the studies and provides justification for examination of moderators across studies that may account for such differences. Examination of the pooled estimated and Q statistic suggested that significant heterogeneity, χ2(11) = 31.20, p < .01, was detected from the pooled estimate. Based on this result, both use of a random-effects model and examination of moderators were warranted.

Three moderator variables were coded and analyzed for each study: racial discrimination scale, depressive symptom assessment scale type, and sample type. Studies were classified into two sample type categories based on the type of population sampled: college/university versus other. Racial discrimination scale categorized whether the perceived discrimination scale used assessed frequency (i.e., how often), appraisal (i.e., rated stressfulness), or a combination of both types of exposures. Depressive symptom assessment scale type distinguished whether the depressive symptomatology scale used had been directly validated against clinical diagnostic criteria (depression-specific) versus scales that contain items simply linked to depression symptoms (depression-related). Moderators were examined using the STATA 12.0 metareg function. Individual regression analyses were conducted for each moderator to examine the individual association of each variable with the overall pooled-effect estimate. Due to small sample size, method of moments was used to estimate variances. All analyses were conducted in STATA 12.0.

Results

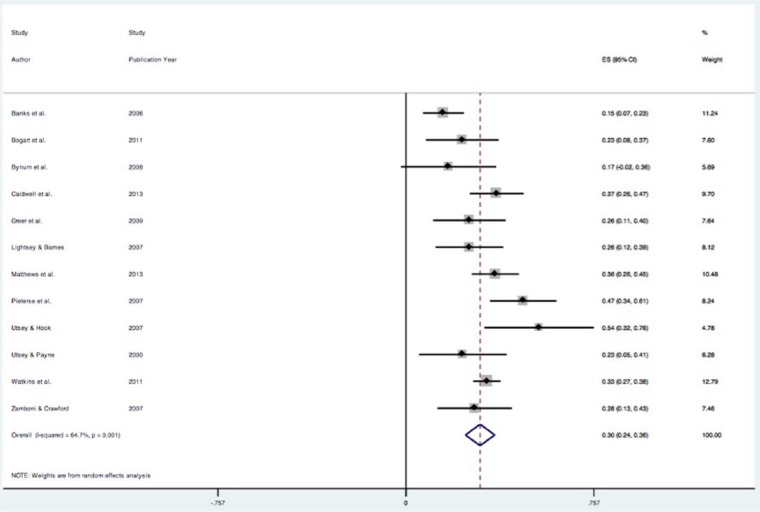

The aggregated correlation effect size between discrimination and depression for all 12 studies was r = .290 (z = 0.299), 95% CI [r = .235, .343], as reported in Figure 2 using fisher’s z score. This significant positive relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms suggests that greater perceived discrimination was associated with greater depressive symptoms among Black men. Findings further indicate evidence of potential heterogeneity among the studies (Q = 31.20, degrees of freedom = 11, p < .01). The I2 index indicated heterogeneity in effect sizes among studies. Approximately 65% of the total variability among the effect sizes was caused by true heterogeneity among the studies.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies indicating effects (Fisher’s z-score) of perceived discrimination on depressive symptomatology in Black men.

Note. Net effect is shown for each individual study, with lines extending from the symbols representing 95% confidence intervals. Sizes of data markers indicate relative weight of study on overall estimate.

Secondary analyses conducted with metaregression examined potential differences of the mean effect sizes based on different levels of the specified moderators. Table 2 reports the heterogeneity (τ2) for each moderator model, the proportion of heterogeneity accounted for by the moderator used, and meta-analysis results stratified by the moderator. Contrary to expectations, the relationship between exposure to discrimination and subsequent depressive symptoms was not moderated by racial discrimination scale, sample type, or depression scale (see Table 2) exerting statistically significant influence, indicating that heterogeneity among the studies were not explained by the selected moderators.

Table 2.

Effect of Moderators (Metaregression Analysis).

| Moderator | No. of studies | Coefficient (mean effect size, r) | 95% confidence interval for r |

Proportion, I2 | Between-study variance, τ2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||||

| Racism scale type | |||||||

| Frequency | 4 | Index | 66.79% | 0.007 | −9.29% | ||

| Appraisal | 6 | −0.031 | −0.186 | 0.126 | |||

| Combined | 2 | 0.081 | −0.130 | 0.285 | |||

| Depression scale type | |||||||

| Depression-specific | 8 | Index | 61.85% | 0.007 | −5.01% | ||

| Depression-related | 4 | -0.042 | −0.188 | 0.107 | |||

| Sample type | |||||||

| College | 4 | Index | 67.68% | 0.007 | −12.20% | ||

| Other | 8 | 0.013 | −0.149 | 0.175 | |||

Note. Between-study variance (τ2) assessed by method-of-moments–based estimate.

Discussion

Consistent with previous research among other racial and ethnic groups (Lee & Ahn, 2011; Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Pieterse et al., 2012), this study reported a significant positive relationship between discrimination and depressive symptomatology among Black men. Similar to Pieterse et al. (2012), the current study identified an association between discrimination and mental health outcomes. The findings from this study add to that offered by Pieterse et al. by calculating an overall correlation effect size between discrimination and depression for Black men. That correlation effect size was 0.290, higher than the correlation effect size that Pieterse et al. reported when examining the relationship between discrimination and mental health among Black adults. This study provides evidence that the mental health of Black men residing in the United States is negatively affected by exposure to discrimination.

The findings of the current study are similar to another meta-analysis conducted by Lee and Ahn (2011) among an Asian and Asian American sample that identified a similar positive average correlation between psychological distress and perceived racial discrimination (r = .23). Current study findings support the conclusion that discrimination is a significant factor in understanding depression among Black men. It is important to note that the effect size did not vary as a function of type of racial discrimination, by depression scales, or by sample type. This is important because it provides evidence of the robustness of the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms, providing additional validation for prior theory positing this association.

Limitations

Few studies have examined the relationship between discrimination and depression specifically in Black men; therefore the data to include in this meta-analysis were limited. In addition, all of the studies included were of a cross-sectional design; the lack of available longitudinal studies among Black men is a limitation for inferring causality in the relationship between discrimination and depression. Although the theory and previous research guiding this investigation posit that exposure to discrimination leads to stress and eventual depressive symptoms, a plausible alternative hypothesis might be that depressed individuals perceive more unfair treatment from others around them, as a function of their own pessimistic thought patterns (Burt, Zembar, & Niederehe, 1995; Mathews & MacLeod, 1994; J. M. G. Williams, Mathews, & McLeod, 1996). This specific alternative is not supported by other research; however, at least one longitudinal study conducted nationally among Black American adults suggests that discrimination perceptions are not influenced by poor mental health status (Brown et al., 2000). This is further supported by several other recent longitudinal and experimental studies (Gee & Walsemann, 2009; Pavalko, Mossakowski, & Hamilton, 2003; Schulz et al., 2006). Due to the self-reported scales used in assessing discrimination across the 12 included studies, this particular meta-analysis examined only perceived discrimination and it should be noted that actual discrimination (presence of evidence of a discriminatory event) may potentially have different effects on mental health than perceived discrimination. Last, this investigation includes published only articles in well-known literature databases. This could potentially result in an overestimation of the effect size, given that unpublished articles may be more likely to include negative results.

Future Directions and Implications

Conducting a meta-analysis provides a basic but full view of the current state of the literature examining discrimination and depression among Black men. In particular, it allows researchers to fully examine what factors are included and what key factors might be needed to improve the state of the literature. From the examination of the literature in this study, there were several potential limitations to the current literature identified. As suggested by Pieterse et al. (2012), there is a need for more specificity in the period of time or setting that discrimination occurred.

Currently there are no “gold standards” for assessing depressive symptomatology and perceived discrimination. Studies use a variety of scales and measurements, making a thorough comparison across studies difficult because various scales may measure different aspects of these constructs (D. R. Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). The majority of the studies included in this analysis draw on common screens used within the epidemiological population research. Although many of the screeners used are common, many of the depression screeners used are typically not validated among African American men and are not necessarily restricted solely to depression. Given that the scales/screeners used among the studies are not necessarily restricted solely to depression, there is also a possibility that other constructs of and/or related to depression/depressive symptomatology and/or similar mental health outcomes strongly related to depression may also be captured in the scales/screeners used. This is a limitation throughout the literature that may complicate the complete understanding of the observed effects found throughout studies reporting the effects of discrimination and depression/depressive symptomatology. However, this does not negate the overall significant effect occurring between perceived discrimination and mental health (e.g., depressive symptomatology or a similar construct) among Black men. Despite the scale or measurements used to analyze the two variables of interest, each of the scales used across the studies have been validated and/or linked with depression and a consistent relationship was reported among the studies analyzed. This suggests that the reported effect is robust to scales/screeners used; however, there is a strong need for standardized measures of depression/depressive symptomatology scales that are validated among Black men.

Current conventions of data reporting were a key limiting factor in this analysis. Some studies were excluded from this analysis because they lacked the appropriate reporting statistics or stratifications needed to properly explore the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms in Black men. It should also be noted that this analysis examined perceived discrimination in general and did not specify specific types of perceived discrimination and its effects on depression. In addition, the majority of studies focused exclusively on perceived racial discrimination, and only a few studies systematically examined other potential types of perceived discrimination (e.g., sexual orientation, health status). Although a positive relationship was reported in all included studies despite types of perceived discrimination (e.g., race, gender, class) examined, the specific type of perceived discrimination examined could influence the strength/magnitude of the effect size reported for perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms.

It also is important to recognize that other aspects of identity may be sources of perceived discrimination that eventually contribute to depressive symptoms among Black men. Among other salient experiences and identities that might intersect significantly with sex and race are sexual orientation and sexual identity identification. These may affect perceptions of inclusion or ostracism in relationships with the African American and wider communities, provoke perceptions of stigma, inhibit or potentiate help-seeking, or even be associated with special stressors or health risks. How one identifies thus may affect their perception and/or experience. In the current analytic sample of this study, however, only 2 of the 12 eligible studies included information on participants’ sexual orientation, and none reported sexual identity or its relationships with relevant outcomes in any detailed fashion other than limited categories based on unidimensional scales. The small number of studies, the limited measurement of sexual behavior patterns, and range of sexual orientations represented within these two studies did not permit clear analysis of the impact of discrimination based on sexual orientation or sexual identity. There are many important areas in which Black men might experience discrimination, and it is not clear that the full range of those experiences have been captured in the current literature. Future work should further explore the impact that other characteristics (e.g., sexual identity, sexual orientation—self-labeled or not, HIV status) may have on the discrimination–depressive symptom effect reported among Black men.

Discrimination typically is measured in (one of) two ways: everyday discrimination and major “lifetime” discrimination. These tap into different aspects of discrimination; however, included articles did not always clarify which was being measured. Specifically, major “lifetime” discrimination focuses on unfair treatment that may have occurred over a wider time frame and is primarily concerned with events that influence one’s socioeconomic status (Ayalon & Gum, 2011; Kessler et al., 1999). Conversely, everyday discrimination reflects more recent events that are primarily concerned with attacks on one’s character that may or may not influence their socioeconomic status (Ayalon & Gum, 2011; Kessler et al., 1999). Everyday discrimination appears to have a greater impact on mental health than major lifetime discrimination (Kessler et al., 1999). Ultimately, the magnitude and significance of the effect examined in this analysis may differ depending on which type of discrimination is being assessed. Future research will also need to consider the deleterious effects of interactions among these forms of discrimination, as well as other possible indicators of discrimination and ethnicity-related social stress. For example, internalization of anti-Black biases appears to accelerate biological aging, both directly and differentially, among Black males facing high levels of racial discrimination (Chae et al., 2014). Therefore, there is also a need for standardized measures of perceived discrimination scales that are validated among Black men.

Despite the limitations associated with the current study and the state of the literature, the findings of the current study indicate robustness of the effect reported between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Nonetheless, construction of more uniform and refined instruments with greater specificity regarding specific types of perceived discrimination is greatly warranted for a more thorough assessment and understanding of the perceived discrimination–depression relationship. Future research should further examine the potential gender differences that may be reported within different racial and ethnic groups in the perceived discrimination–depression relationship. For instance, an examination of whether statistically significant differences in the perceived discrimination–depressive symptom effect size between Black men and women should be evaluated. Being able to assess differences in effects between genders could be influential in determining appropriate interventions for particular groups. Additionally, it is also important to compare across both race/ethnicity and age-groups.

Despite these concerns, this meta-analysis has several implications for the public health arena. Results of this analysis emphasize the need for a more thorough understanding of the mechanisms and effects of perceived discrimination, to inform ways to proactively improve the health outcomes for Black men. Recognizing perceived discrimination as a key contributor to depression allows for potentially improved and more effective treatment regimens for Black men, particularly in understanding the significance of educating and bringing awareness to public health practitioners on the relevance of perceived discrimination in treating Black male patients.

Current practitioners may need additional training on how to competently assess, treat, and provide resources to individuals who may be dealing with various forms of perceived discrimination. For example, current treatment for depression consists of therapy, medication, or a combination of both. This finding may influence practitioners to opt for and encourage Black men seeking help for depression to engage in therapy or a combination of both therapy and medication. This type of treatment regimen may provide better care and improved health outcomes for Black men because therapy may provide additional coping mechanisms to the individual. As suggested by Pieterse et al. (2012), providing more clarity on the significant influence of perceived discrimination on depression along with a framework of potential effective coping strategies that encompass empowerment and resistance techniques (Pieterse, Howitt, & Naidoo, 2011) may be influential in reducing the current effect reported within this relationship. Also in line with Pieterse et al. (2012) suggestions, an assessment of perceived discrimination experienced among Black men seeking mental health resources across all public health fields should become a part of standard protocol.

Finally, researchers must continue to investigate, dissect, and thoroughly understand the mechanisms of perceived discrimination (e.g., types) and its detrimental effects on mental health (e.g., depression) within Black men to find a path toward ultimately enhancing the health of Black men. A more extensive examination of other potential moderators within this population should also be assessed to allow a better understanding of mechanisms that may be contributing to this effect. Ultimately, findings of this study highlight critical steps needed within the public health arena to improve the resources used and provided to better assess and meet the needs of Black men residing in the United States.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Cancer Society. (2009). Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2009-2010. Atlanta, GA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2014). Depression. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/depress/

- Ayalon L., Gum A. M. (2011). The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 15, 587-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks K. H., Kohn-Wood L. P., Spencer M. (2006). An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Mental Health Journal, 42, 555-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., Brown G. (1996). BDI-II Beck Depression Inventory manual. New York, NY: Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L. M., Wagner G. J., Galvan F. H., Banks D. (2010). Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 53, 648-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L. M., Wagner G. J., Galvan F. H., Landrine H., Klein D. J., Sticklor L. A. (2011). Perceived discrimination and mental health symptoms among Black men in HIV. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 295-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L. W., Higgins J. P., Rothstein H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. London, England: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell L. N., Jacobs D. R., Jr., Williams D. R., Pletcher M. J., Houston T. K., Kiefe C. I. (2007). Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 166, 1068-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell L. N., Kiefe C. I., Williams D. R., Diez-Roux A. V., Gordon-Larsen P. (2006). Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in african americans in the CARDIA study. Social Sciene & Medicine, 63(6), 1415-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe N. R., Schmitt M. T., Harvey R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135-149. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. N., Williams D. R., Jackson J. S., Neighbors H. W., Torres M., Sellers S. L., Brown K. T. (2000). “Being Black and feeling blue”: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race & Society, 2, 117-131. [Google Scholar]

- Burt D. B., Zembar M. J., Niederehe G. (1995). Depression and memory impairment: A meta-analysis of the association, its pattern, and specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 285-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum M. S., Best C., Barnes S. L., Thomoseo Burton E. (2008). Private regard, identity protection and perceived racism among African American males. Journal of African American Studies, 12, 142-155. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell C. H., Antonakos C. L., Tsuchiya K., Assari S., De Loney E. H. (2013). Masculinity as a moderator of discrimination and parenting on depressive symptoms and drinking behaviors among nonresident African-American fathers. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14, 47-58. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health Services. (2001). Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity: A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Current depression among adults—United States, 2006 and 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59, 1229-1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov//injury/wisqars/index.html

- Chae D. H., Nuru-Jeter A. M., Adler N. E., Brody G. H., Lin J., Blackburn E. H., Epel E. S. (2014). Discrimination, racial bias, and telomere length in African American men. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46, 103-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R., Anderson N. B., Clark V. R., Williams D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54, 805-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (1980). After effects of stress on human performance and social behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 82-108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R. (1993). Symptom checklist-90-R. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R. (2000). The Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual (3rd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R., Lipman R. S., Rickels K., Ulenhuth E., Covi L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R., Meisarotis N. (1983). The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595-605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman T. A., Williams D. R., Jackson J. S. (1997). Race, place, and discrimination. Perspectives of Social Problems, 9, 231-261. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin A. J., Boyd-Franklin N. (2000). Invisibility syndrome: A clinical model of the effects of racism on African-American males. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G., Spencer M. S., Chen J., Takeuchi D. (2007). A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1275-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G., Walsemann K. (2009). Does health predict the reporting of racial discrimination or do reports of discrimination predict health? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 1676-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg P. E., Kessler R. C., Birnbaum H. G., Leong S. A., Lowe S. W., Berglund P. A., Corey-Lisle P. K. (2003). The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 1465-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer T. M., Laseter A., Asiamah D. (2009). Gender as a moderator of the relation between race-related stress and mental health symptoms for African Americans. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 295-307. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond W. P. (2012). Taking it like a man: Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health, 102(S2), S232-S241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell S. P. (1997. a). Development and initial validation of scales to measure racism-related stress. Unpublished manuscript, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell S. P. (1997. b). The Racism and Life Experiences Scales (RaLES). Unpublished manuscript.

- Harrell S. P. (2000). A multi-dimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 42-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L., Olkin I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Andrews G., Colpe L. J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D. K., Normand S. L. T., . . . Zaslavsky A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Mickelson K. D., Williams D. R. (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 208-230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H., Klonoff E. A. (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22, 144-168. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. L., Ahn S. (2011). Racial discrimination and Asian mental health: A meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 463-489. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner D., Henke R. M. (2008). What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50, 401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightsey O. R., Barnes P. W. (2007). Discrimination, attributional tendencies, generalized self-efficacy and assertiveness as predictors of psychological distress among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 33(2), 27-50. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A. D., Murray C. J. L. (1998). The global burden of disease, 1990-2020. Nature Medicine, 4, 1241-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A., MacLeod C. (1994). Cognitive approaches to emotion and emotional disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 45, 25-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews D. D., Hammond W. P., Nuru-Jeter A., Cole-Lewis Y., Melvin T. (2013). Racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among African-American men: The mediating and moderating roles of masculine self-reliance and John Henryism. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14, 35-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2006). Health, United States, 2006 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: Author. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y. (2006). A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Ethnicity & Health, 35, 888-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe E. A., Richman L. S. (2009). Perceived discrimination and heath: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko E. K., Mossakowski K. N., Hamilton V. J. (2003). Does perceived discrimination emotional health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 18-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Meyerhoefer C. D., Zuvekas S. H. (2013). The effect of depression on labor market outcomes (Working Paper No. 19451). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w19451

- Pierce C. (1974). Psychiatric problems of the Black minority. In Arieti S. (Ed.), American handbook of psychiatry (pp. 512-523). New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse A. L., Carter R. T. (2007). An examination of the relationship between general life stress, racism-related stress, and psychological health among Black men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 101-109. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse A. L., Howitt D., Naidoo A. V. (2011). Racial oppression, colonization and self-efficacy: Towards an empowerment model for individuals of African heritage. In Mpofu E. (Ed.), Counseling people of African ancestry (pp. 93-108). London, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse A. L., Todd N. R., Neville H. A., Carter R. T. (2012). Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59, 1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401. [Google Scholar]

- Rich J. (2000). The health of African American men. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 569(1), 149-159. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. E., Sobhan M. (1992). Symptoms of depression in adolescence: A comparison of Anglo, African, and Hispanic Americans. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21, 639-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond W., Flegal K., Furie K., Go A., Greenlund K., Haase N., . . . Hong Y. (2008). Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation, 117, e25-e146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A. J., Gravlee C. C., Williams D. R., Israel G. M., Rowe Z. (2006). Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results form a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1265-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen P. R., Bowden M. (2006). Sleep disturbance mediates the relationship between perceived racism and depressive symptoms. Ethnicity & Disease, 16, 21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, S41-S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey S. O. (1999). Development and validation of a short form of the Index of Race-Related Stress (IRRS)-brief version. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 32, 149-167. [Google Scholar]

- Utsey S. O., Hook J. N. (2007). Heart rate variability as a physiological moderator of the relationship between race-related stress and psychological distress in African Americans. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey S. O., Payne Y. (2000). Psychological impacts of racism in a clinical versus normal sample of African American men. Journal of African American Men, 5(3), 57-72. [Google Scholar]

- Veit C. T., Ware J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 730-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E., Mengesha M. (2013). Depression in African American men: A review of what we know and where we need to go from here. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(2 Pt. 3), 386-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins D. C., Green B. L., Rivers B. M., Rowell K. L. (2006). Depression and Black men: Implications for future research. Journal of Men’s Health & Gender, 2, 227-235. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins D. C., Hudson D. L., Caldwell C. H., Siefert K., Jackson J. S. (2011). Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K. B., Sturm R., Sherbourne C. D., Meredith L. S. (1996). Caring for depression. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. (1999). The nature of stressors. In Horwitz A. V., Scheid T. L. (Eds.), A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems (pp. 176-197). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. (2003). The health of men: Structured inequalities and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 724-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Gonzalez H. M., Neighbors H., Nesse R., Abelson J. M., Sweetman J., Jackson J. S. (2007). Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the national survey of American life. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Mohammed S. A. (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Neighbors H. W., Jackson J. S. (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings form community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 200-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Williams-Morris R. (2000). Racism and mental health: The African American experience. Ethnicity & Health, 5, 243-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Yu Y., Jackson J. S., Anderson N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. M. G., Mathews A., McLeod C. (1996). The emotional Stroop task and psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 3-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2008). The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2009). Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major Risks. Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni B. D., Crawford I. (2007). Minority stress and sexual problems among African-American gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 569-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]