Abstract

Many researchers take for granted that men’s mental health can be explained in the same terms as women’s or can be gauged using the same measures. Women tend to have higher rates of internalizing disorders (i.e., depression, anxiety), while men experience more externalizing symptoms (i.e., violence, substance abuse). These patterns are often attributed to gender differences in socialization (including the acquisition of expectations associated with traditional gender roles), help seeking, coping, and socioeconomic status. However, measurement bias (inadequate survey assessment of men’s experiences) and clinician bias (practitioner’s subconscious tendency to overlook male distress) may lead to underestimates of the prevalence of depression and anxiety among men. Continuing to focus on gender differences in mental health may obscure significant within-gender group differences in men’s symptomatology. In order to better understand men’s lived experiences and their psychological well-being, it is crucial for scholars to focus exclusively on men’s mental health.

Keywords: social determinants of health, mental health, depression

Introduction

Ultimately, gender differences are largely caused by things other than gender. . . . The more we understand these forces and their sources and consequences, the more reasons and power we gather to change them.

—Rosenfield and Smith (2009, p. 267).

Extensive research examines gender differences in mental health (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1976; Gove, 1978; Kessler et al., 1994; Rosenfield, 1980). This scholarship focuses mostly on women’s issues, a result of necessary feminist attempts to make women’s experiences a more central area of study. A singular focus on women unintentionally led to a neglect of men with stereotypically feminine disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety; Smith & Mouzon, 2014)1 as well as a poor understanding of stereotypically masculine symptoms such as substance abuse and violence. This article assesses the extant research as a starting point for further investigation of men’s mental health.

Most research in gender and mental health supports two findings: (a) men and women have approximately equal rates of disorder overall (at least among the disorders that have been assessed; Rieker, Bird, & Lang, 2010; Rosenfield & Smith, 2009) and (b) men and women tend to experience different kinds of psychiatric illnesses (Rosenfield & Mouzon, 2013; Rosenfield & Smith, 2009; Rosenfield, Vertefuille, & Mcalpine, 2000). Girls and women are thought to have higher rates of “internalizing” disorders like depression and anxiety, while boys and men are considered to be at increased risk of “externalizing” troubles such as aggressive behavior, substance abuse, oppositional defiant disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Jackson & King, 2004; Kessler & Wang, 2008), and antisocial personality disorder (Merikangas et al., 2010). Men exhibit more aggression, violence toward people and animals, destruction of property, lying, and stealing (Merikangas et al., 2010). These disorders impede the development of high-quality relationships, an additional burden given men’s fewer social relationships (Courtenay, 2003). Studies suggest that compared with women, drugs and alcohol more often interfere with men’s lives (Wilsnack et al., 2000), men use alcohol in greater quantities, and experience greater physical consequences such as blackouts and hallucinations from substances (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

Much of the extant work on gender and mental health has inadvertently led to an absence of scholarship on men’s mental health specifically, partly due to a reliance on gender comparisons (men vs. women) rather than examination of within-gender differences in mental health outcomes. Measurement and clinician bias likely influence the current findings, which may lead to problematic assumptions about gendered symptoms. Given that men are less likely than women to seek help for mental health problems (Galdas, Cheater, & Marshall, 2005), to have symptoms that fit standard measurement tools (Martin, Neighbors, & Griffith, 2013), and to have their mental health problems identified by primary care physicians (Borowsky et al., 2000), men’s mental illness is likely underestimated, leading to incomplete or misleading scholarship.

Research that compares men and women’s mental health neglects the similarities between men and women’s experiences of stress, instead focusing on the different outcomes of stress (e.g., Elliott, 2013). It is possible that substance abuse and violence mask depression and anxiety in men (Addis, 2008; Horwitz, White, & Howell-White, 1996; Rosenfield, Phillips, & White, 2006) or that traditionally masculine symptoms like addiction and aggression share the same underlying causes as depression and anxiety (Horwitz et al., 1996; Rosenfield & Smith, 2009; Simon, 2002). Another possibility is that there is a functional difference between direct indicators of misery (e.g., symptoms of depression) and correlates of misery (e.g., addictions; Hill & Needham, 2013), an argument borne out by the fact that depression and alcohol intake are positively correlated among women and men (Ross & Mirowsky, 2003). Given the lower likelihood of null results being published (Franco, Malhotra, & Simonovits, 2014), studies reporting few or no gender differences in mental health problems may be less likely to find a place in the scientific literature.

Men often hide psychological problems and are reluctant to report symptoms (Lee & Owens, 2002; O’Brien, Hunt, & Hart, 2005), leading some to suggest that there is a “silent epidemic” for men particularly regarding depression (Real, 1998). It is likewise possible that significant measurement bias is embedded in screening tools and diagnostic instruments used in community samples (e.g., Uebelacker, Strong, Weinstock, & Miller, 2009) and that clinicians are less attuned to diagnosing traditionally feminine symptoms in male patients (see Smith & Hemler, 2014, on classification and diagnosis). Researchers, policy makers, and clinicians alike must question the validity and reliability of current measurement tools for detecting symptoms the same way for men and women, and focus on what factors might be particularly relevant for men’s experiences.

Though this article discusses mental illness generally, its focus is on depression because almost one in five Americans will experience it in their lifetime (Harvard Medical School, 2007b), and recent studies report that men experience depression at higher rates than previously documented. While the prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) among men was 2.74% from 1991 to 1992, there was a statistically significant increase to 4.88% from 2001 to 2002 (Compton, Conway, Stinson, & Grant, 2006). Studies have either projected (Dunlop & Mletzko, 2011) or reported (Klerman & Weissman, 1989) that rates of traditionally feminine disorders may be on the rise for men. Popular work (cf. Real, 1998) suggests similar trends, though the underlying cause of this epidemiological shift is yet unclear. In an effort to explore the areas of men’s mental health that have not been the focus of previous research, this review suggests that there are, in fact, significant numbers of men struggling with what have traditionally been considered “female disorders.”

In the existing epidemiological literature on gender and mental health, there are significant areas of uncertainty regarding men’s mental health, and by extension, gender and mental health generally. This article challenges the accepted wisdom about what makes men’s experiences of mental health different from women’s, and suggests a need for new empirical explorations of the classic assumptions about gender and mental health. This review concludes with suggestions regarding future empirical analyses that may offer insight into which symptoms men may be either most vulnerable to or most protected from. Insight into men’s mental health offers wide-ranging implications for an understanding of the impacts of gender socialization and gender roles on mental health, gender bias in the health care system, and how to improve community data collection efforts and clinical and policy interventions.2

Traditional Assumptions Regarding Gender and Mental Health

The presumption of a gender divide along internalizing/externalizing lines is problematic (Hill & Needham, 2013). The 2001 to 2003 National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) indicates that 8.6% of women and 4.9% of men met criteria for MDD in the past 12 months (Harvard Medical School, 2007a). Based on 2012 Census data, these estimates correspond to 10.4 million women but also 5.6 million men (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Even though women disproportionately experience depression, significant numbers of men do as well. Similarly, the rate for any anxiety disorder is higher for women—23.4% compared with 14.3% for men—but this corresponds to 37.3 million women and also 22.1 million men. In other words, internalizing disorders are also prevalent among men (just as some externalizing disorders are also prevalent among women). The conventional wisdom, however, would lead us to believe that mood and anxiety disorders are only a significant issue for women. Furthermore, when comparing within-group gender differences for men, it is clear that more men (14.3%) have anxiety disorders than any other type of disorder (7.7 % had mood disorders, 11.7% had impulse control disorders, and 4.5% and 2.2% of men had alcohol and drug disorders, respectively3; Harvard Medical School, 2007a). In other words, a singular focus on gender differences distracts us from the fact that internalizing disorders are a serious problem for men.

There are four conventional explanations for gender differences in mental health: socialization, help seeking, coping, and gender stratification each of which are reviewed below. In addition, the current work adds to the growing literature on measurement bias, offering insight into whether gender differences are real or an artifact of the diagnostic measures used in surveys. Last, this review addresses clinician bias, including how it may be influenced by traditional assumptions about gender differences in mental health. Although none of the factors reviewed here offer a complete explanation for what causes men’s distress and diagnosable mental health conditions, each of them could benefit from further analysis.4

Socialization: The Effect of Internalized Gender Roles and Expectations on Mental Health

Men and women are traditionally socialized to act, think, and emote differently based on gender. Contemporary gender roles date back to industrialization when men worked in the public sphere, doing work that yielded power and economic privilege, which research suggests results in better mental health (Lennon & Rosenfield, 1994). Dominant conceptions of masculinity depict and encourage boys and men to be assertive, competitive, and independent, which fits with work in the public sphere (Connell, 1995; Rosenfield, Lennon, & White, 2005). The assumption is that men are protected against the stress of having low control and power because of socialization and employment status. However, the stressful nature of male breadwinner expectations or the emasculation of not being able to fulfill this role may lead to negative health outcomes (Springer, 2010).

Men are less likely to be empathetic and emotionally dependent on intimate partners (Hirschfeld, Klerman, Chodoff, Korchin, & Barrett, 1976; Turner & Turner, 1999). Many theorists suggest that this can be protective against depression, but it can also foster problems with aggression and other externalizing problems (Hagan, Gillis, & Simpson, 1985; Heimer & Coster, 1999; Miedzian, 2002; Ohbuchi, Ohno, & Mukai, 1993; Rosenfield et al., 2000; Turner & Turner, 1999). Men are less likely to express troubles, and are less likely to discuss sensitive issues and solve emotional problems. Socialization into appropriate expressions of emotion or “feeling rules” (Hochschild, 1979) is different for men and women (Simon, 2002). In addition to expectations of assertiveness, dominance, aggression, independence, and risk taking, men are expected to keep hidden any emotion that might be defined as effeminate or weak—this generally includes nurturance, caring, sensitivity, and communicativeness. Anger, on the other hand, is encouraged5 (Simon, 2007). Men are not only primed to exhibit externalizing symptoms but also to cover up internalizing symptoms for fear of stigma (Simon, 2014), which would make depression and anxiety complex to diagnose in men.

One key question is whether enacting masculinity protects men from experiencing depression and anxiety or if it simply pushes men to hide emotions or report symptoms in ways inconsistent with diagnostic criteria (Safford, 2008). Masculinity influences whether or not men seek help from professionals or people in their social networks (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Galdas et al., 2005). Emslie, Ridge, Ziebland, and Hunt (2006) concluded that men who have been diagnosed with depression often learn to accept their diagnosis by reintegrating it into a masculine identity that emphasizes control, strength, and responsibility; others construct alternate masculine identities that involve, for example, creativity or intelligence. Rosenfield et al. (2005, 2006) suggest that the gendered internalizing/externalizing divide is partly attributable to the differences in self-salience between men and women. Men tend to privilege the self over others, more often taking their feelings out on others, while women spare others, directing emotions inward instead (Rosenfield & Smith, 2009). However, Björkqvist (1994) argues that women are “covertly” aggressive (even if not physically aggressive); women’s aggression may be overlooked much in the same way as men’s depression.

Literature on socialization and mental health would benefit from addressing the impact of socialization on clinicians and researchers whose unconscious internalization of roles and expectations leads to particular diagnosis and evaluation of symptoms (Smith & Hemler, 2014). Socialization is an important area for future investigation not just for those experiencing symptoms but also for professionals.

Help-Seeking Behavior

Research suggests that men’s lack of help seeking renders them less likely to be diagnosed than women (Culbertson, 1997; Oliver, Pearson, Coe, & Gunnell, 2005). This does not mean that men are less likely to actually be ill, however. Men seek general medical care far less often than women, especially for preventive health reasons (Courtenay, 2000), but also for mental health care (Oliver et al., 2005). Men may view mental health care seeking as even more discretionary than general medical care because the physical health of men’s bodies is largely tied to the valued male gender role ideal of breadwinning (not to mention physical and sexual prowess more generally; Brannon, 1976; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Men are more likely than women to list stigma avoidance as a factor for not seeking care (Ojeda & Bergstresser, 2008). Men’s lower rates of mental health care seeking may partially explain their higher rates of externalizing disorders; if men are depressed and do not seek help, they might turn to substances rather than social support, antidepressants, or therapy.

Though the literature on help seeking is largely gender-comparative, one notable exception is masculinity studies. Despite not being the statistical norm, hegemonic masculinity is the most idealized form of masculinity, embodied in strength, independence, financial success, confidence, and heterosexual prowess (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Hegemonic masculinity is most easily achieved by White, middle-class men in the United States, while other subordinated masculinities are more prevalent among working-class men and men of color (e.g., Majors & Billson, 1993; Pyke, 1996). Recent sociological research reports that men who strongly endorse hegemonic masculinity ideals are less likely to seek general preventive care than men with weaker adherence to these ideals (Springer & Mouzon, 2011), though no research has examined the association between hegemonic masculinity and mental health outcomes or mental health care–seeking among men. Although limited, literature suggests that clinicians and researchers recognize that men do not seek help often enough, as evidenced by research on men’s help seeking for MDD, for which men are half as likely as women to receive treatment (Wang et al., 2005). Men’s reluctance to seek health care is consistent with their socialization; help seeking is viewed as a weakness, in direct contrast to valued masculine traits such as strength and independence.

Coping Strategies, Coping Resources, and Social Support

Coping strategies reflect cognitive or behavioral attempts to manage a stressor that is perceived as taxing beyond one’s ability to adapt. Sociologists often conceptualize coping as a buffering mechanism in that stress is less harmful to health when one holds high levels of mastery, self-esteem, or social support (Thoits, 2009). Coping strategies are often classified as either problem-focused or emotion-focused (though meaning-based coping is an important, understudied area of research; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Problem-focused coping involves efforts to change or confront the actual stressor, while emotion-focused coping encompasses efforts aimed at changing one’s emotions regarding the stressor through avoidance and tension relief (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Emotion-focused coping is more common when circumstances are perceived as uncontrollable, while problem-solving coping is more often employed when individuals perceive having personal control or mastery over a situation (see Thoits, 1991, for an exception). Often coined primary “personal resources,” self-esteem and mastery are both associated with positive mental health outcomes (Thoits, 2009).

When faced with a stressor, men more often employ problem-focused coping strategies such as actively confronting or strategizing about a problem (Matud, 2004; Ptacek, Smith, & Dodge, 1994; Thoits, 1991; Zwicker & DeLongis, 2010). Emotion-focused coping, more often employed by women and frequently measured by behaviors such as rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999) and worry (Hong, 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999), is associated with higher psychological distress than problem-focused coping (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978; Watson & Sinha, 2008). Given that men have higher levels of self-esteem (McMullin & Cairney, 2004) and mastery (Pearlin, Nguyen, Schieman, & Milkie, 2007) than women, men are expected to use problem-focused coping when confronted by stressors. Some propose that gender differences in coping strategies account in part for men’s lower prevalence of internalizing disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999). There is, however, increasing evidence that the gendered nature of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping is overstated. For example, men may more often use distraction via drugs and alcohol (Dawson, Grant, & Ruan, 2005) and men may experience rumination and worry.

Social support is the most commonly studied coping resource within the stress-health literature. Men typically have smaller, less diverse, and less emotionally supportive primary social networks than women (Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002). Men are also less likely than women to report having a confidant although they more often report that their spouse is their main confidant (Due, Holstein, Lund, Modvig, & Avlund, 1999; Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002). Men’s relatively weaker involvement in social relationships may protect from the health-deteriorating “dark” aspects of social relationships such as emotional strain and “significant other” stress that may arise from people in their social network (e.g., Beals & Rook, 2006). In short, men’s lower rates of mental health care utilization, smaller and less diverse social networks, and lower propensity to divulge feelings to friends, family, and health care providers may predispose them to exhibiting distress in an externalizing fashion—typically aggression, violence, or alcohol/substance use.

Gender Stratification

Women’s greater burden of internalizing disorders vis-à-vis men has also been attributed in part to their overall lower position in the socioeconomic hierarchy of the United States (Elliott, 2001; Mirowsky & Ross, 1995) as indicated by their lower average earnings (Denavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015), occupational status (Rollero, Fedi, & Piccoli, 2016), and until fairly recently, their lower average educational background (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). Despite the fact that men tend to have higher socioeconomic status than women, there is substantial variation in socioeconomic status among men, for whom low-income and education levels are both positively associated with depression (Inaba et al., 2005; Ross & Mirowsky, 2006). Further research is needed that focuses exclusively on men’s mental health with an eye to how indicators of social stratification increase the risk of internalizing (as well as externalizing) disorders for men.

Whereas socialization, help seeking, coping, and gender stratification seek to explain the internalizing/externalizing gender divide, there are other, emerging arguments suggesting that men’s rates of internalizing disorders may be underestimated. Specifically, both measurement and clinician bias can result in inaccurate estimates of men’s mental health problems.

Understudied Factors Affecting Rates of Men’s Mental Health

Measurement Bias

Psychiatric diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders rely on symptoms as indicators of illness, culminating in a single yes/no indicator of whether or not criteria for a psychiatric disorder are met. For example, the screening criteria for MDD include either depressed mood or diminished pleasure; those who meet these criteria must also experience at least five symptoms including but not limited to significant weight or sleep changes, fatigue, and suicidality. To receive a diagnosis, these symptoms must cause significant distress or impairment in functioning (Spitzer & Wakefield, 1999, p. 1857).

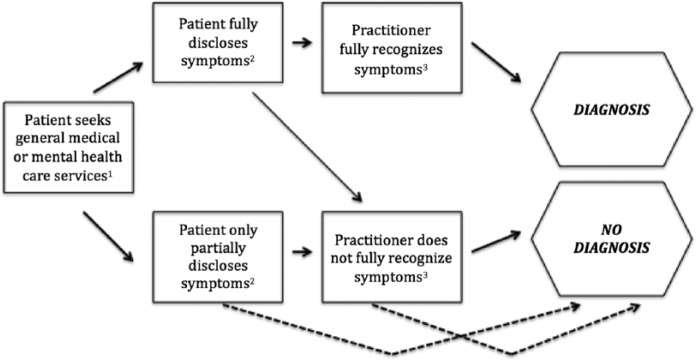

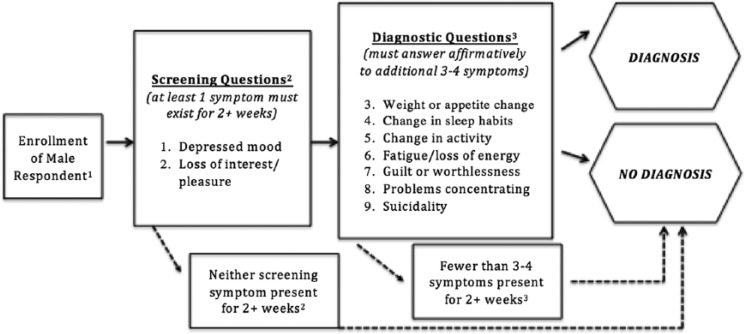

Figures 1 and 2 represent the complex pathways to diagnosis of MDD for men in clinical and community research settings, respectively. In both scenarios, men are at decreased odds of receiving a diagnosis of depression compared with women. In clinical assessments (Figure 1), men are underrepresented because they are less likely to seek care than women (Courtenay, 2000; Oliver et al., 2005), are less likely to report depressive symptoms when they do seek care (Courtenay, 2000), and are less likely to be diagnosed with depression (Swami, 2012). In epidemiological studies (Figure 2), such as the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), data are collected from community-based samples so the fact that men are less likely to seek help for symptoms of depression does not directly affect prevalence statistics. Men may still be less likely to be diagnosed with depression in such studies because they are less likely to participate in data collection efforts (Korkeila et al., 2001), are less likely to report or even experience the screening symptoms that precipitate follow-up questions (Martin et al., 2013), and are less likely to report or even experience the symptoms used to diagnose major depression when they do report the screening symptoms (Martin et al., 2013). NCS (and its replication, NCS-R) data are widely used in research on gender differences in depression (Kessler, 1998, 2003; Merikangas et al., 2010; Silverstein, 1999, 2002), and therefore are the key studies that may underestimate the prevalence of men’s depression and other internalizing disorders.

Figure 1.

Pathways and potential bias in detecting major depressive disorder among men in clinical settings.

1Men seek health care less often than women (Courtenay, 2000; Oliver et al., 2005). 2Men are unlikely to disclose symptoms (Courtenay, 2000). 3Practitioners are less likely to recognize depression symptoms among men (Swami, 2012).

Figure 2.

Potential bias in detecting major depressive disorder among men in community epidemiological surveys.

1Men may be less likely to participate in data collection efforts (Korkeila et al., 2001). 2Men may be less likely to report and/or experience these screening symptoms (Martin et al., 2013). 3Men may be less likely to report and/or experience these diagnostic symptoms (Martin et al., 2013).

In contrast to clinical and epidemiological studies that rely on discrete diagnostic categories, self-report screening scales for general distress such as the Center for Epidemiological Scale for Depression (CES-D) and the Beck Depression Inventory, conceptualize mental health as a continuum of symptomatology. Scores represent ranges, for example, of 0/low through 60/high for the 20-item version of the CES-D, based on whether and how frequently each symptom is present. As with studies on gender and depression, studies that gauge gender differences in general distress report that women report more symptoms than men (Elliott, 2013; Mirowsky & Ross, 1995). In both clinical and community-based samples, and regardless of whether depression is measured categorically or continuously, social desirability factors stemming from norms of masculinity may influence men to underreport symptoms.

The following section reviews studies that focus on measurement issues. Though women more frequently attempt suicide, men succeed more often (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Women who attempt to take their lives are often diagnosed with MDD and treated, while men’s higher rates of completed suicides mean they will never have the chance to be detected or treated. Men would then appear less depressed overall. Severity is also a factor in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and CES-D assessment. Though women have a higher prevalence of depression overall, when impairment was included as a criterion, gender differences disappear (Angst et al., 2002). In other words, at the extreme end of the depression spectrum, gender differences appear to level out. Perhaps men do not have lower rates of depression than women, but lower rates of mild and moderate depression and similar rates of severe depression (Newmann, 1984). It may be the case that moderate symptoms are overlooked, less common, or nonexistent for men, or that men may not mention symptoms until they are severe.

Some suggest that men’s lower prevalence of depression occurs because women are more likely than men to somaticize distress, exhibiting symptoms such as fatigue, appetite disturbance, and sleep disturbance (and often accompanied by pain and anxiety; Silverstein, 2002). These symptoms are often screening questions on diagnostic questionnaires (Douzenis, Rizos, Paraschakis, & Lykouras, 2008; Romans, Tyas, Cohen, & Silverstone, 2007). If distress scales and psychiatric diagnostic instruments overrepresent somatic items (as opposed to cognitive or affective symptoms), they would consequently underestimate depression rates for men. Research examining “pure depression” symptoms (Silverstein, 1999)—cognitive/affective symptoms such as loss of interest, loss of pleasure, and feelings of worthlessness or guilt—might uncover that this, too, is underreported for men. Current data are needed to draw clear conclusions regarding somaticization, though descriptive U.S. data from three different nationally representative data sets report that men have roughly half the rate of somatic depression yet similar prevalence of pure depression (Kessler et al., 1994; Silverstein, 1999, 2002; Uebelacker et al., 2009).

Clinician Bias

Measurement bias in epidemiological surveys may also be responsible for inaccurate assumptions about men’s mental health, leading to implicit clinician bias and statistical discrimination. Implicit bias refers to “attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner” (Kirwin Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, 2015, p. 6), while statistical discrimination is as a process whereby “providers apply correct information about a group to reduce clinical uncertainty about an individual patient” (McGuire et al., 2008, p. 532). Statistical discrimination has a more conscious underpinning in that clinicians may purposefully draw on their epidemiological training (demonstrating, e.g., that men are far less likely to experience depression and anxiety) in order to render clinical decisions about individual patients, while implicit bias is thought to be more of an unconscious, automatic bias that may or may not be steeped in scientific literature. Both phenomena can lead to underdiagnosis of men’s depression and anxiety.

Feminizing depression and anxiety in medical education and practice may lead to underestimates of men’s mental health problems. Clinicians are less likely to recognize these symptoms among men and men are less likely to disclose depressive symptoms for fear of failing to embody normative, male-typed expressions of distress. The sociology of diagnosis (Jutel, 2011), specifically literature on symptom classification (Smith & Hemler, 2014), suggests that clinicians are trained to see the patients in ways consistent with their professional socialization. These biases also affect laypersons. For example, an experimental study of the general British population reported that both men and women were less likely to identify depression in vignettes involving men than those involving women. Women were also more likely than men to recognize depression in male vignettes (Swami, 2012). This is consistent with the growing literature on statistical discrimination in clinical practice based on race/ethnicity (e.g., McGuire et al., 2008). While clinician bias has not yet been fully assessed in terms of gender, it is an important factor in the diagnosis of low-income people and people of color (see Groopman, 2008).

Conclusion

Extant research suggests that men are less depressed, less anxious, and more likely to be aggressive and have substance abuse problems than women. The possible etiology of these differences crosses a range of factors including socialization, help seeking, coping and social support, gender stratification, and measurement and clinician bias. Yet men’s mental health problems have not been examined sui generis. This does not mean that men and women are vastly different. The factors that affect men’s and women’s mental health are likely much more similar than they are distinct but scholars must first examine men’s issues explicitly to test this hypothesis. The scant research on men’s mental health focuses on substance abuse and aggression, important dimensions of men’s mental health, especially in a hypermasculine culture that encourages these behaviors for men.6 However, depression and anxiety are diagnosed among men only somewhat less often than they are for women, and anxiety and depression pose significant threats to men’s well-being (Harvard Medical School, 2007a). Overlooking these men bolsters the notion that men are more likely than women to externalize, and ignores men who internalize. This raises deeper questions about the problem of associating internalizing disorders with women and externalizing disorders with men. Conceptualizing men as externalizers (other-directed) also ignores the damage that externalizing disorders cause to the self; externalizing disorders indeed have an internalizing dimension.

Given long-standing biases in research and clinical practice, women are often thought to be “The Stressed Sex”7 (Freeman & Freeman, 2013). However, due namely to reasons addressed here—expression, measurement, and clinician bias—there is not nearly enough knowledge regarding the nature of men’s experiences of psychiatric problems. What is clear is that few tools carefully measure the symptoms men tend to experience, and that men are less likely to seek treatment and disclose their troubles. Taken together, these factors indicate a high likelihood of underdiagnosis for men in internalizing (and externalizing) disorders, which is damaging to individuals, families, economic productivity, and social cohesion. One crucial area for further research involves understanding how to encourage men to seek treatment. Other overlooked areas for future study regarding men’s mental health are the role that implicit clinician bias (Blair, Steiner, & Havranek, 2011; Chapman, Kaatz, & Carnes, 2013), statistical discrimination (Balsa & McGuire, 2001; McGuire et al., 2008), and diagnostic errors (Groopman, 2008; Smith & Hemler, 2014) play in the lower rates of diagnosis of internalizing symptoms among men. Extant research begs the question of whether men are more likely to be diagnosed with the behavior (e.g., substance abuse) rather than the emotional underpinnings of the addiction (e.g., depression).

Suggestions for Future Analysis

Researchers ought to examine the factors most important to men’s symptomatology and experiences. As the field moves forward, there is a need for a basic reexamination of the gender divide in symptomatology, which several scholars have pointed to since the turn of the century. Elliott (2013) recently proffered important longitudinal analysis using community-based samples, which is paramount to building a male model of distress and help seeking that can be used to inform both health policy and clinical practice. This work echoes Rieker and Bird (2000, p. 104), who suggest that “[b]ecause the model of the social determinants of depression was built on assessments of the impact of female disadvantage, it is not easily generalizable to men’s excess rates of alcohol and drug dependence” (quoted in Hill & Needham, 2013, p. 86). Current models also fail to capture men’s depression or anxiety. It is crucial to further unpack the nature of the relationships among addictive behaviors, stress, and emotional states to determine whether the etiology of these symptoms is similar (in both magnitude and direction) for men and women. Researchers must be able to distinguish between specific measures of illness (dependent variables) and predictors or other correlates of illness (independent variables).

Additional work in this area should also incorporate intersectionality theories, which highlight the need to investigate how multiple social identities converge to produce various combinations of both privilege and oppression. Although it is crucial to study men, there is also a need for additional work that explores how the experience of male gender and mental health varies by other locations in the social structure, such as race/ethnicity, nativity status, and social class (i.e., Griffith, Metzl, & Gunter, 2011; Hankivsky, 2012). Men are not a monolithic category; the circumstances that put men at risk for mental disorders (or protect them from certain disorders), as well as how men express emotions (Simon, 2014), are largely shaped by social location. Focusing on men within epidemiological data sets such as the National Comorbidity Study–Replication, the National Latino and Asian American Study, and the National Survey of American Life could provide particularly valuable insights into demographic and social factors that predict both internalizing and externalizing disorders among diverse groups of men.

Examining the impact of masculinities on men’s mental health is another promising direction for future research. Empirical evidence suggests men’s more dramatic emotional responses to physical illness like cancer are due to the challenges that being ill present to the ideals of hegemonic masculinity (Pudrovska, 2010). Self-salience offers a potential mechanism to explore the gender difference in internalizing versus externalizing behaviors. Hill and Needham (2013) propose that self-salience may be an especially strong predictor of men’s mental health. Longitudinal analysis of self-salience in diverse data sets could offer the following contributions to the field: (a) allow for assessment of cohort changes in self-salience among men and women, given women’s progress in the labor market and trends toward more equitable family lives; (b) permit analysis of how perceptions of the self and the extent to which people privilege the self over others changes across the life course for men and women; (c) enable intersectional analysis of how gender, self-salience, and mental disorder processes differ by race/ethnicity and social class, both cross-sectionally and across the life course (see important work in this area among adolescents; Rosenfield, 2012; Rosenfield et al., 2006).

The role of symptom identification processes is also important for future research. More attention to men’s lower likelihood to recognize symptoms of depression and other troubles highlights the importance of clinicians, and the important role women might play (romantic partners or other family members) in identifying risk among men who may not recognize their symptoms as related to depression. There is suggestive experimental research that reports men are less likely than women to recognize depression among men (i.e., Swami, 2012). Longitudinal data would permit researchers to tease out causal ordering of symptoms (presence and magnitude), help seeking, and diagnosis among men. This type of analysis—and those outlined above—are crucial in building the male model of distress that is currently absent in the literature. Only then will scholars and clinicians be able to identify whether there is bias in the current assessment tools (in both research and clinical practice) and tailor appropriate interventions for men.

Women with stereotypically masculine disorders (e.g., substance abuse, violence, and suicide) are likewise overlooked.

Wherever possible, instead of making gender comparisons, this article focuses on unique factors that influence men’s experiences, diagnosis, and disorder rates, so as not to assume without empirical evidence that men’s problems are necessarily different. This is not to undermine the important work on women’s mental health and gender generally, but rather to add specificity to the extant body of knowledge. Nor is this to suggest that men’s mental health is monolithic; this analysis is a point of departure.

Drug and alcohol disorders are reported separately because the NCS-R calculation of “any substance disorder” includes 11.6% of men who were dependent on nicotine, a condition that is not traditionally considered to be an externalizing disorder.

The authors focus primarily on social factors involved in gender and mental health research, although emergent scholarship on biosocial factors is promising (see Springer, Mager Stellman, & Jordan-Young, 2012).

Women have surprisingly high rates of anger, however (Mirowsky & Schieman, 2008; Schieman, 2010).

There is also a need for more research on these conditions. We do not suggest that the focus be removed from externalizing disorders in favor of internalizing disorders, but rather that we should challenge the gender assumptions associated with each.

Freeman and Freeman use the term “sex” and “gender” interchangeably.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Addis M. E. (2008). Gender and depression in men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15, 153-168. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00125.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Addis M. E., Mahalik J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58, 5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J., Gamma A., Gastpar M., Lépine J.-P., Mendlewicz J., Tylee A. Depression Research in European Society Study. (2002). Gender differences in depression: Epidemiological findings from the European DEPRES I and II studies. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252, 201-209. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0381-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa A. I., McGuire T. G. (2001). Statistical discrimination in health care. Journal of Health Economics, 20, 881-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals K. P., Rook K. S. (2006). Gender differences in negative social exchanges: Frequency, reactions, and impact. In Bedford V. H., Formaniak B. (Eds.), Men in relationships: A new look from a life course perspective (pp. 197-217). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Björkqvist K. (1994). Sex differences in physical, verbal, and indirect aggression: A review of recent research. Sex Roles, 30, 177-188. doi: 10.1007/BF01420988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair I. V., Steiner J. F., Havranek E. P. (2011). Unconscious (implicit) bias and health disparities: Where do we go from here? Permanente Journal, 15(2), 71-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky S. J., Rubenstein L. V., Meredith L. S., Camp P., Jackson-Triche M., Wells K. B. (2000). Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15, 381-388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon R. (1976). The male sex role: Our culture’s blueprint for manhood, what it’s done for us lately. In David D., Brannon R. (Eds.), The forty-nine percent majority: The male sex role (pp. 1-49). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Suicide fact sheet. Atlanta, GA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman E. N., Kaatz A., Carnes M. (2013). Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 1504-1510. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton W. M., Conway K. P., Stinson F. S., Grant B. F. (2006). Changes in the prevalence of major depression and comorbid substance use disorders in the United States between 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 2141-2147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (1995). Masculinities (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W., Messerschmidt J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19, 829-859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50, 1385-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2003). Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. International Journal of Men’s Health, 2(1), 1-30. doi: 10.3149/jmh.0201.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson F. (1997). Depression and gender: An international review. American Psychologist, 52, 25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Grant B. F., Ruan W. J. (2005). The association between stress and drinking: Modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 40, 453-460. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denavas-Walt C., Proctor B. (2015). Income and poverty in the United States: 2014 (Current Population Reports). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-252.html [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B. P., Dohrenwend B. S. (1976). Sex differences and psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Sociology, 81, 1447-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douzenis A., Rizos E., Paraschakis A., Lykouras L. (2008). Male depression: Discrete differences between the two sexes. Psychiatrikē = Psychiatriki, 19, 313-319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Due P., Holstein B., Lund R., Modvig J., Avlund K. (1999). Social relations: Network, support and relational strain. Social Science & Medicine, 48, 661-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop B. W., Mletzko T. (2011). Will current socioeconomic trends produce a depressing future for men? British Journal of Psychiatry, 198, 167-168. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M. (2001). Gender differences in causes of depression. Women & Health, 33(3-4), 183-198. doi: 10.1300/J013v33n03_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M. (2013). Gender differences in the determinants of distress, alcohol misuse, and related psychiatric disorders. Society and Mental Health, 3, 96-113. doi: 10.1177/2156869312474828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie C., Ridge D., Ziebland S., Hunt K. (2006). Men’s accounts of depression: Reconstructing or resisting hegemonic masculinity? Social Science & Medicine, 62, 2246-2257. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219-239. doi: 10.2307/2136617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A., Malhotra N., Simonovits G. (2014). Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345, 1502-1505. doi: 10.1126/science.1255484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Freeman J. (2013). The stressed sex: Uncovering the truth about men, women, and mental health (1st ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer R., Stansfeld S. A. (2002). How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: A comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close persons.” Social Science & Medicine, 54, 811-825. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdas P. M., Cheater F., Marshall P. (2005). Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49, 616-623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gove W. R. (1978). Sex differences in mental illness among adult men and women: An evaluation of four questions raised regarding the evidence on the higher rates of women. Social Science & Medicine. Part B: Medical Anthropology, 12, 187-198. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(78)90032-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Metzl J. M., Gunter K. (2011). Considering intersections of race and gender in interventions that address US men’s health disparities. Public Health, 125, 417-423. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groopman J. (2008). How doctors think (Reprint ed.). Boston, MA: Mariner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J., Gillis A. R., Simpson J. (1985). The class structure of gender and delinquency: Toward a power-control theory of common delinquent behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 90, 1151-1178. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O. (2012). Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1712-1720. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Medical School. (2007. a). 12-Month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Medical School; Retrieved from http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Medical School. (2007. b). Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Medical School; Retrieved from http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_Lifetime_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Heimer K., Coster S. D. (1999). The gendering of violent delinquency. Criminology, 37, 277-318. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1999.tb00487.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T. D., Needham B. L. (2013). Rethinking gender and mental health: A critical analysis of three propositions. Social Science & Medicine, 92, 83-91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld R. M., Klerman G. L., Chodoff P., Korchin S., Barrett J. (1976). Dependency-self-esteem-clinical depression. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 4, 373-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85, 551-575. [Google Scholar]

- Hong R. Y. (2007). Worry and rumination: Differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 277-290. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz A. V., White H. R., Howell-White S. (1996). The use of multiple outcomes in stress research: A case study of gender differences in responses to marital dissolution. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37, 278-291. doi: 10.2307/2137297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba A., Thoits P. A., Ueno K., Gove W. R., Evenson R. J., Sloan M. (2005). Depression in the United States and Japan: Gender, marital status, and SES patterns. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 2280-2292. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. A., King A. R. (2004). Gender differences in the effects of oppositional behavior on teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 215-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutel A. G. (2011). Putting a name to it: Diagnosis in contemporary society. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C. (1998). Sex differences in DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 53(4), 148-158. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C. (2003). Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 74, 5-13. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00426-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., McGonagle K. A., Zhao S., Nelson C. B., Hughes M., Eshleman S., . . . Kendler K. S. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Wang P. S. (2008). The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 115-129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwin Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. (2015). State of the science: Implicit bias review 2015. Columbus: The Ohio State University; Retrieved from http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/implicit-bias-review/ [Google Scholar]

- Klerman G. L., Weissman M. M. (1989). Increasing rates of depression. Journal of the American Medical Association, 261, 2229-2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkeila K., Suominen S., Ahvenainen J., Ojanlatva A., Rautava P., Helenius H., Koskenvuo M. (2001). Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. European Journal of Epidemiology, 17, 991-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Owens R. G. (2002). Issues for a psychology of men’s health. Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 209-217. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007003215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon M. C., Rosenfield S. (1994). Relative fairness and the division of housework: The importance of options. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 506-531. [Google Scholar]

- Majors R., Billson J. M. (1993). Cool pose: The dilemmas of Black manhood in America (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Touchstone. [Google Scholar]

- Martin L. A., Neighbors H. W., Griffith D. M. (2013). The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs women: Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 1100-1106. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matud M. P. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1401-1415. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire T. G., Ayanian J. Z., Ford D. E., Henke R. E. M., Rost K. M., Zaslavsky A. M. (2008). Testing for statistical discrimination by race/ethnicity in panel data for depression treatment in primary care. Health Services Research, 43, 531-551. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00770.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullin J. A., Cairney J. (2004). Self-esteem and the intersection of age, class, and gender. Journal of Aging Studies, 18, 75-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2003.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., He J.-P., Burstein M., Swanson S. A., Avenevoli S., Cui L., . . . Swendsen J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980-989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedzian M. (2002). Boys will be boys: Breaking the link between masculinity and violence. New York, NY: Lantern Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J., Ross C. E. (1995). Sex differences in distress: Real or artifact? American Sociological Review, 60, 449-468. doi: 10.2307/2096424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J., Schieman S. (2008). Gender, age, and the trajectories and trends of anxiety and anger. Advances in Life Course Research, 13, 45-73. doi: 10.1016/S1040-2608(08)00003-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newmann J. P. (1984). Sex differences in symptoms of depression: Clinical disorder or normal distress? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 25, 136-159. doi: 10.2307/2136665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2004). Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 981-1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S., Larson J., Grayson C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7, 1061-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R., Hunt K., Hart G. (2005). “It”s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate”: Men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 503-516. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohbuchi K., Ohno T., Mukai H. (1993). Empathy and aggression: Effects of self-disclosure and fearful appeal. Journal of Social Psychology, 133, 243-253. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1993.9712142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda V. D., Bergstresser S. M. (2008). Gender, race-ethnicity, and psychosocial barriers to mental health care: An examination of perceptions and attitudes among adults reporting unmet need. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 317-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M. I., Pearson N., Coe N., Gunnell D. (2005). Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 297-301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Nguyen K. B., Schieman S., Milkie M. A. (2007). The life-course origins of mastery among older people. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 164-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Schooler C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19, 2-21. doi: 10.2307/2136319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek J. T., Smith R. E., Dodge K. L. (1994). Gender differences in coping with stress: When stressor and appraisals do not differ. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 421-430. doi: 10.1177/0146167294204009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pudrovska T. (2010). Why is cancer more depressing for men than women among older White adults? Social Forces, 89, 535-558. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyke K. D. (1996). Class-based masculinities: The interdependence of gender, class, and interpersonal power. Gender & Society, 10, 527-549. doi: 10.1177/089124396010005003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Real T. (1998). I don’t want to talk about it: Overcoming the secret legacy of male depression (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Rieker P. P., Bird C. E. (2000). Sociological explanations of gender differences in mental and physical health. In Bird C. E., Conrad P., Fremont A. (Eds.), Handbook of medical sociology (pp. 98-113). New York, NY: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Rieker P. P., Bird C. E., Lang M. E. (2010). Understanding gender and health: Old patterns, new trends, and future directions. In Bird C. E., Conrad P., Fremont A. M., Timmermans S. (Eds.), Handbook of medical sociology (pp. 98-113). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Rollero C., Fedi A., Piccoli N. D. (2016). Gender or occupational status: What counts more for well-being at work? Social Indicators Research, 128, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Romans S. E., Tyas J., Cohen M. M., Silverstone T. (2007). Gender differences in the symptoms of major depressive disorder. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 195, 905-911. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181594cb7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S. (1980). Sex differences in depression: Do women always have higher rates? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 33-42. doi: 10.2307/2136692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S. (2012). Triple jeopardy? Mental health at the intersection of gender, race, and class. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1791-1801. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S., Lennon M. C., White H. R. (2005). The self and mental health: Self-salience and the emergence of internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 323-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S., Mouzon D. (2013). Gender and mental health. In Aneshensel C. S., Phelan J. C., Bierman A. (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 277-296). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S., Phillips J., White H. (2006). Gender, race, and the self in mental health and crime. Social Problems, 53, 161-185. doi: 10.1525/sp.2006.53.2.161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S., Smith D. (2009). Gender and mental health: Do men and women have different amounts or types of problems? In Scheid T. L., Brown T. N. (Eds.), A handbook for the study of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 256-267). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S., Vertefuille J., Mcalpine D. D. (2000). Gender stratification and mental health: An exploration of dimensions of the self. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, 208-223. doi: 10.2307/2695869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. E., Mirowsky J. (2003). Social causes of psychological distress (2nd ed.). Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. E., Mirowsky J. (2006). Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: Resource multiplication or resource substitution? Social Science & Medicine, 63, 1400-1413. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safford S. M. (2008). Gender and depression in men: Extending beyond depression and extending beyond gender. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15, 169-173. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00126.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S. (2010). The sociological study of anger: Basic social patterns and contexts. In Potegal M., Stemmler G., Spielberger C. (Eds.), International handbook of anger (pp. 329-347). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein B. (1999). Gender difference in the prevalence of clinical depression: The role played by depression associated with somatic symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 480-482. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein B. (2002). Gender differences in the prevalence of somatic versus pure depression: A replication. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 1051-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. W. (2002). Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 1065-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. W. (2007). Contributions of the sociology of mental health for understanding the social antecendents, social regulation, and social distribution of emotion. In Avison W. R., McLeod J. D., Pescosolido B. A. (Eds.), Mental health, social mirror (pp. 239-274). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. W. (2014). Sociological scholarship on gender differences in emotion and emotional well-being in the United States: A snapshot of the field. Emotion Review, 6, 196-201. doi: 10.1177/1754073914522865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. T., Hemler J. (2014). Constructing order: Classification and diagnosis. In Jutel A. G., Dew K. (Eds.), Social issues in diagnosis: An introduction for students and clinicians (pp. 15-32). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. T., Mouzon D. M. (2014). Men’s mental health. In Cockerham W., Dingwall R., Quah S. R. (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of health, illness, behavior, and society (pp. 1489-1494). Chicester, England: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R. L., Wakefield J. C. (1999). DSM-IV diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: Does it help solve the false positives problem? American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1856-1864. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer K. W. (2010). Economic dependence in marriage and husbands’ midlife health: Testing three possible mechanisms. Gender & Society, 24, 378-401. doi: 10.1177/0891243210371621 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Springer K. W., Mager Stellman J., Jordan-Young R. M. (2012). Beyond a catalogue of differences: A theoretical frame and good practice guidelines for researching sex/gender in human health. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1817-1824. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer K. W., Mouzon D. M. (2011). “Macho men” and preventive health care: Implications for older men in different social classes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 212-227. doi: 10.1177/0022146510393972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swami V. (2012). Mental health literacy of depression: Gender differences and attitudinal antecedents in a representative British sample. PLoS One, 7(11), e49779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. (1991). Gender differences in coping with emotional distress. In Eckenrode J. (Ed.), The social context of coping (pp. 107-138). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. (2009). Sociological approaches to mental illness. In Brown T. N. (Ed.), A handbook for the study of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 106-124). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner H. A., Turner R. J. (1999). Gender, social status, and emotional reliance. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 360-373. doi: 10.2307/2676331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker L. A., Strong D., Weinstock L. M., Miller I. W. (2009). Use of item response theory to understand differential functioning of DSM-IV major depression symptoms by race, ethnicity and gender. Psychological Medicine, 39, 591-601. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). Annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States, states, counties, and Puerto Rico commonwealth and municipios: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2015). Educational attainment: Current population study (Historical Time Series Tables No. Table A-1). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/historical/

- Wang P. S., Berglund P., Olfson M., Pincus H. A., Wells K. B., Kessler R. C. (2005). Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 603-613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. C., Sinha B. (2008). Emotion regulation, coping, and psychological symptoms. International Journal of Stress Management, 15, 222-234. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.15.3.222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack R. W., Vogeltanz N. D., Wilsnack S. C., Harris T. R., Ahlström S., Bondy S., . . . Weiss S. (2000). Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: Cross-cultural patterns. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 95, 251-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker A., DeLongis A. (2010). Gender, stress, and coping. In Chrisler J. C., McCreary D. R. (Eds.), Handbook of gender research in psychology (pp. 495-515). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]