Abstract

N-Myristoyltransferase (NMT) represents a promising drug target within the parasitic protozoa Trypanosoma brucei (T. brucei), the causative agent for human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) or sleeping sickness. We have previously validated T. brucei NMT as a promising druggable target for the treatment of HAT in both stages 1 and 2 of the disease. We report on the use of the previously reported DDD85646 (1) as a starting point for the design of a class of potent, brain penetrant inhibitors of T. brucei NMT.

Introduction

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) or sleeping sickness is prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa1 with an estimated “at risk” population of 65 million.2 The causative agents of HAT are the protozoan parasites Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense(3,4) transmitted through the bite of an infected tsetse fly. HAT progresses through two stages. In the first stage (stage 1), the parasites proliferate solely within the bloodstream. In the second, late stage (stage 2), the parasite infects the central nervous system (CNS) causing the symptoms characteristic of the disease, such as disturbed sleep patterns and often death.5 Currently, there are a number of treatments available for HAT, though none are without issues, including toxicity and inappropriate routes of administration for a disease of rural Africa.6

Research has revealed enzymes and pathways that are crucial for the survival of T. brucei, and based on these studies, a number of antiparasitic drug targets have been proposed.7−10T. bruceiN-myristoyltransferase (TbNMT) is one of the few T. brucei druggable targets to be genetically and chemically validated in both in vitro and in rodent models of HAT.7,11,12 NMT is a ubiquitous essential enzyme in all eukaryotic cells. It catalyzes the co- and post-translational transfer of myristic acid from myristoyl-CoA to the N-terminal glycine of a variety of peptides. Protein N-myristoylation facilitates membrane localization and biological activity of many important proteins.11,13

NMT has been extensively investigated as a potential target for the treatment of other parasitic diseases including malaria,14 leishmaniasis,15 and Chagas’ disease16,17 resulting in the identification of multiple chemically distinct small molecule inhibitors.18 NMT has also been shown to be a potential therapeutic target for human diseases such as autoimmune disorders19 and cancer.20,21

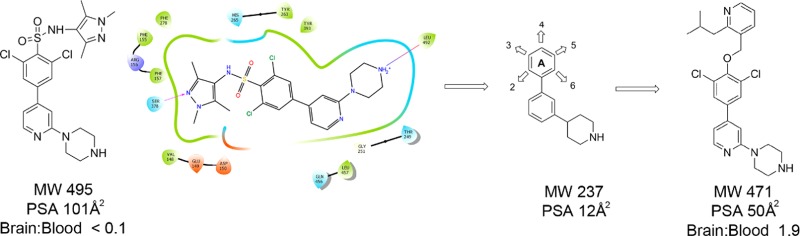

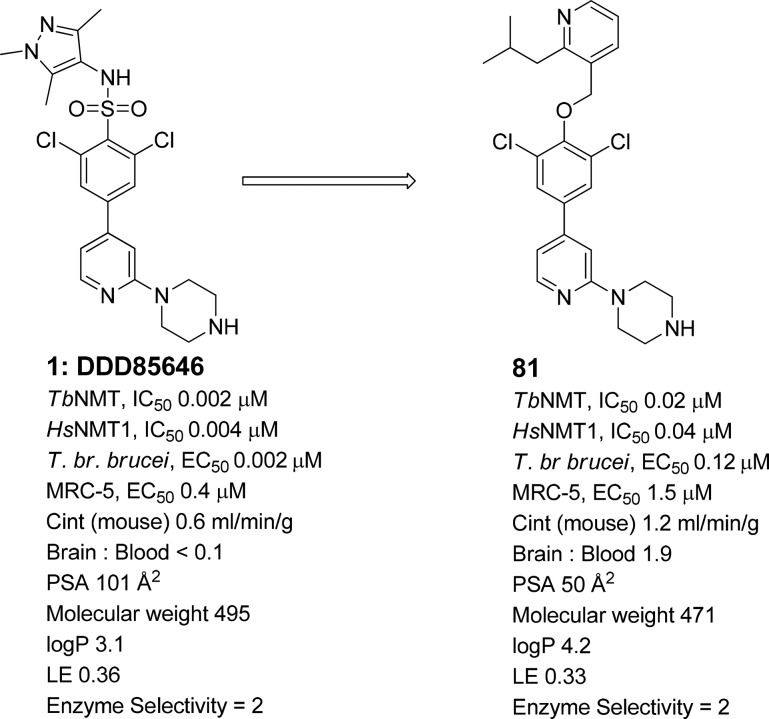

Previously we have reported the discovery of compound 1 (Figure 1),7,22,23 which showed excellent levels of inhibitory potency for TbNMT and T. brucei brucei (T. br. brucei) proliferation in vitro and was used as a model compound to validate TbNMT as a druggable target for stage 1 HAT.7,22 However, 1 is not blood–brain barrier penetrant, a requirement for stage 2 activity. Two approaches were taken to increase the brain penetration of 1. A classical lead optimization approach is described elsewhere.24 This article describes a second approach that used a minimum pharmacophore of 1 aiming to derive a structurally distinct series of potent TbNMT inhibitors with brain penetration, as leads for the identification of suitable candidates for the treatment of stage 2 HAT.

Figure 1.

Compound 1. *Potencies were determined against recombinant TbNMT and HsNMT1, and against bloodstream form T. brucei brucei (T. br. brucei) and MRC-5 proliferation studies in vitro using 10 point curves replicated ≥2. aCalculated using Optibrium STARDROP software. bLigand efficiency (LE), calculated as 0.6·ln(IC50)/(heavy atom count) using T. brucei NMT IC50 potency.25 IC50 values are shown as mean values of two or more determinations. Standard deviation was typically within 2-fold from the IC50. cEnzyme selectivity calculated as HsNMT1 IC50 (μM)/TbNMT IC50 (μM).

Compound Rationale and Design

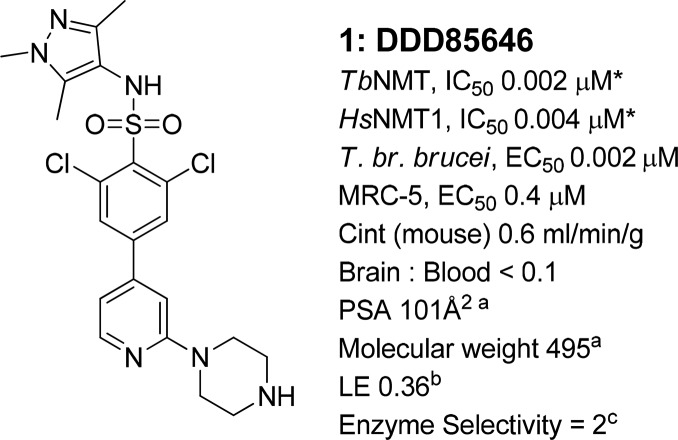

To aid compound design, and to significantly lower molecular weight and polar surface area (PSA), the chlorines and the sulfonamide moieties of 1 were removed to define a minimum pharmacophoric scaffold (Figure 2A). This scaffold was chosen because the piperidine makes a key interaction through the formation of a salt bridge with NMT’s terminal carboxylate.10 This interaction is highly conserved across the binding modes of NMT inhibitors covering multiple chemotypes including 1 (Figure 2B); known antifungal NMT inhibitors such as Roche’s (2-benzofurancarboxylic acid, 3-methyl-4-[3-[(3-pyridinylmethyl)amino]propoxy]-ethyl ester (RO-09-4609),26,27 Searle’s N-[2-[4-[4-(2-methyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)butyl]phenyl]acetyl]-l-seryl-N-(2-cyclohexylethyl)-l-lysinamide (SC-58272)28 (Figure 2C), and Pfizer’s 2-((1R,4R)-4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexanecarboxamido)-N,N-dimethylbenzo[d]thiazole-6-carboxamide (UK-370,485).29 Attempts to crystallize TbNMT had proved to be unsuccessful; therefore, the fungal Aspergillus fumigatus NMT (AfNMT)24,30 was used as a surrogate model for TbNMT in this study. AfNMT is 42% identical to TbNMT; however, within the peptide binding groove the level of identity is 92%. Previously, a selection of molecules from series 1 were assayed against AfNMT and TbNMT using the SPA biochemical assay and pIC50 values compared using linear regression analysis. The pIC50 values were shown to be correlated with an R-squared value of 0.73 suggesting that AfNMT is a suitable surrogate system for study within this chemical series (see Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Development of the chemistry scaffold. (A) Two-dimensional interaction map of 1 bound to AfNMT leading to the design of the minimal scaffold. (B) Crystal structure of 1 bound; key recognition residues are highlighted and labeled. (C) Proposed minimal scaffold (C atoms gold) docked into the crystal structure of AfNMT overlaid with peptomimetic compound PDB 2NMT (C atoms cyan); the key S/T K peptide recognition region is highlighted red.

This minimum pharmacophoric scaffold had low molecular weight (237) and low PSA (12 Å2 to maximize the potential for CNS penetration) from which we could design varied chemistry (Figure 2A) to either access the serine pocket (occupied by the pyrazole moiety in 1) or the peptide recognition region, as seen in the peptomimetic compound highlighted in red (Figure 2C).

Compound Design

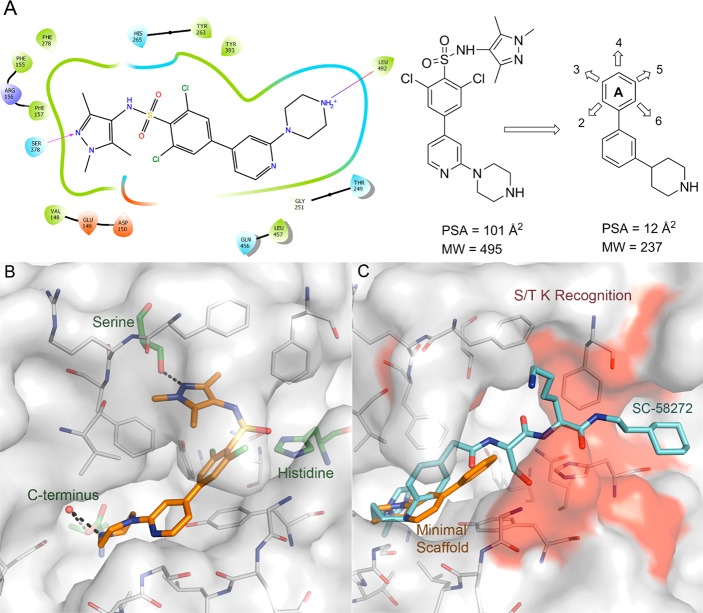

The adopted compound design strategy covered both compounds based on 1 (where common sulfonamide bioisosteres31 and pyrazole mimics were included) and compounds based on the binding pocket structural features, probing these with diverse hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and hydrogen bond donor (HBD) groups. We employed high throughput chemistry, using technologies and techniques such as scavengers and solid supported reagents enabling arrays to be made in parallel. Three different but complementary chemistries of Suzuki couplings, amidations, and Mitsunobu reactions were chosen to explore all positions around ring A (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scaffold array chemistry and design. aFilter parameters calculated using the Optibrium STARDROP software.

Crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB) was an essential part of our chemistry design and presented its own challenges. Improving the BBB permeation of molecules has been widely studied and in silico prediction methods developed based on known CNS penetrant and nonpenetrant compounds.32,33 Examination of the physicochemical properties of molecules and their influence on affecting BBB permeability has suggested some guiding principles and a physicochemical property range to increase the probability of improving the BBB permeability.33 The top 25% CNS penetrant drugs sold in 2004 were found to have mean values of PSA (Å2) 47, HBD 0.8, cLogP 2.8, cLogD (pH 7.4) 2.1, and MW 293. They suggested the following maximum limits when designing compounds as PSA < 90 Å2, HBD < 3, cLogP 2–5, cLogD (pH 7.4) 2–5, MW < 500. As this was the first round of compound design, we restricted the compounds to the following parameters: PSA 40–70 Å2, HBD < 3, cLogP 2–4.5, MW 250–400.

Virtual libraries of all possible compounds that could be constructed from our in-house chemical inventory were constructed and minimized to ensure that a wide region of chemical space was explored, and structures were not biased to one region. Reaction schemes, intermediates, and examples of compounds made are described in the Supporting Information.

Results and Discussion

Scaffold Array Results

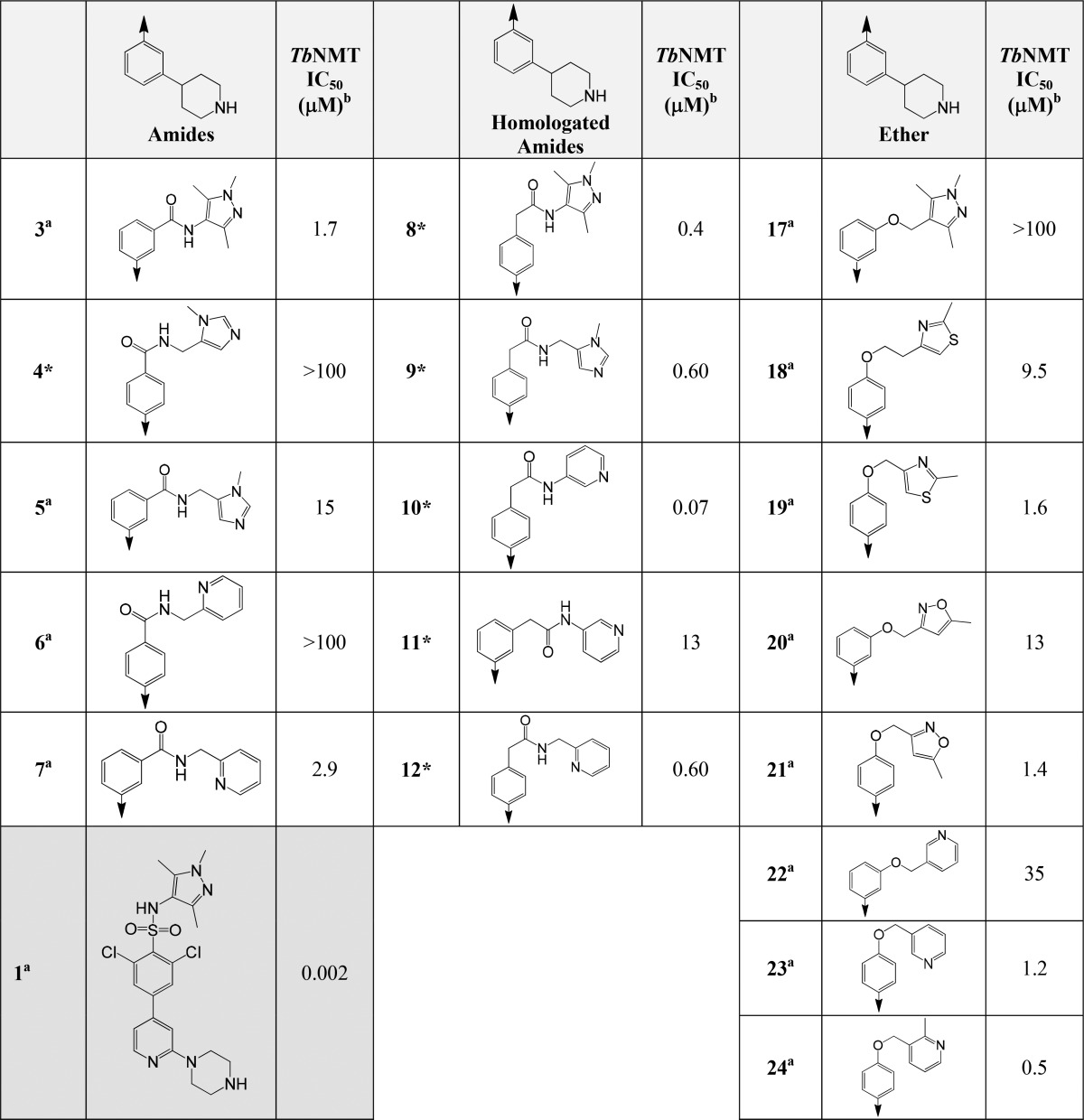

No compounds made in the Suzuki chemistry (1, Figure 3) derived series had a potency <10 μM against TbNMT (see Supporting Information for compounds made). Table 1 shows the potency against TbNMT for selected examples from the amide (3–7), homologated amide (8–12), and ether series (17–24). The most potent compound in the amide series was 3 (TbNMT IC50 1.7 μM). Amides directly linked to the phenyl ring in the 3-position were found to be more potent than the corresponding 4-substituted analogues (5 vs 4 and 7 vs 6). The homologated amide series in comparison to the amide series were on the whole >3-fold more potent (6 vs 12) with the most potent compound achieving a TbNMT IC50 value of 0.07 μM (10). In the homologated amides series the 4-position amides showed greater potency than the corresponding 3-position analogues (the opposite trend to the amide series). Further optimization of both the directly linked and homologated amide series failed to improve the potency or the pharmacokinetic properties.

Table 1. Array Chemistry Selected Results for the Amide, Homologated Amides, and Ether Series.

Compounds greater than 90% pure.

Compounds >95% pure.

IC50 values are shown as mean values of two or more determinations. Standard deviation was typically within 2-fold from the IC50. nd = not determined.

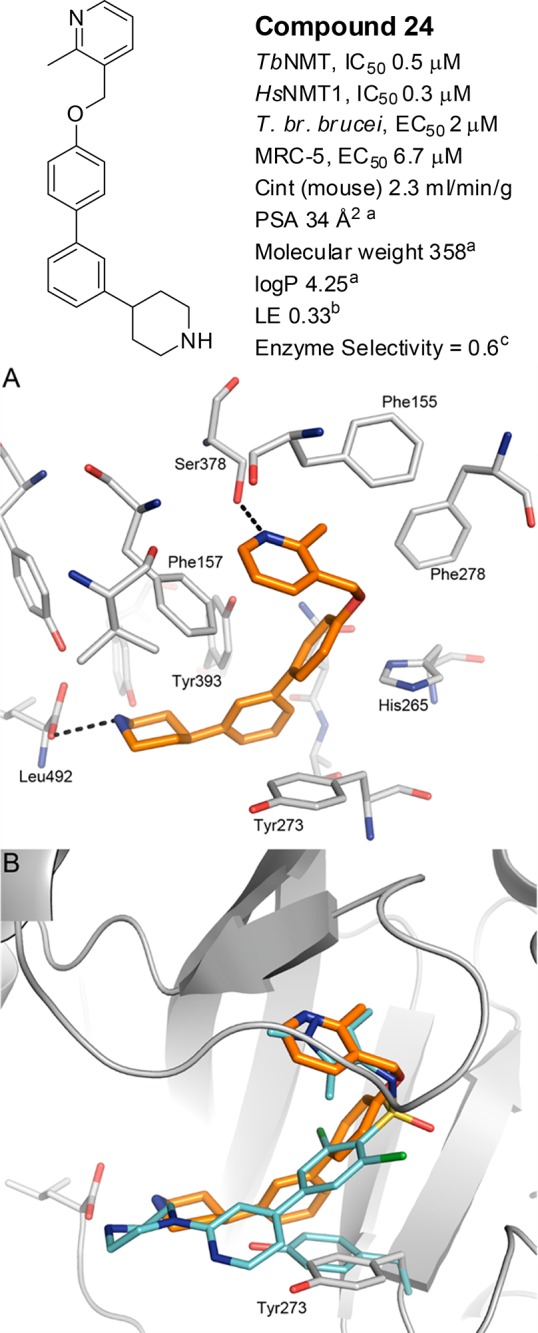

The ether array produced compounds with good levels of activity against TbNMT, the most active of these achieved an IC50 value of 0.5 μM (24). The more potent compounds were substituted in the 4-position, on average showing around 10-fold greater potency over their 3-position analogues, e.g., 3-position compound 22 (35 μM) vs 4-position compound 23 (1.2 μM) or 3-position compound 20 (13 μM) vs 4-position compound 21 (1.4 μM). Interestingly, the replacement of the sulfonamide in structure 1 with an ether linkage (17) was completely inactive against TbNMT (IC50 > 100 μM). This was surprising, as methyl ethers are considered possible sulfonamide bioisosteres.31 Compound 24 was not selective over human NMT (HsNMT1) but exhibited an EC50 of 2 μM in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay, with good microsomal stability and moderate levels of selectivity against proliferating human MRC-5 cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Binding mode of 24. (A) Compound 24 (C atoms gold) bound to AfNMT (C atoms gray). PDB 5T5U. H-bonds are shown as dashed lines and key residues labeled. (B) Comparison of the binding mode of 24 with 1 bound to AfNMT (PDB 4CAX), highlighting the movement of Tyr273. Compound 1 and the side chain of Tyr273 (PDB 4CAX) are shown with cyan C atoms.

The crystal structure of 24 bound to AfNMT (Figure 4A) shows the ligand binds in the peptide binding groove in an overall U-shaped conformation, with the ligand wrapping round the side chain of Phe157. The central aryl rings of 24 lie perpendicular to each other allowing the ligand to sit in the cleft formed by the side chain of Tyr263, Tyr393, and Leu436. The cleft is formed by the movement of the side chain of Tyr273; a feature observed in the binding mode of benzofuran ligands26,27 and subsequent derivatives.34

The pyridyl nitrogen of 24 forms an interaction with Ser378 in a similar orientation as the trimethyl-pyrazole group of 1, and the piperidine moiety interacts directly with the C-terminal carboxyl group of Leu492.

Compound 24 does not interact with His265, an interaction formed by the sulfonamide in 1 (overlaid with 24, Figure 4B), which potentially explained the drop off in potency between 1 (TbNMT 0.002 μM) and 24 (0.5 μM). Despite this loss of activity, 24 had comparable ligand efficiency (LE)35 of 0.33 to 1, LE = 0.36, and in combination with the observed binding mode, gave us confidence that the design strategy was valid.

Optimization of Compound 24

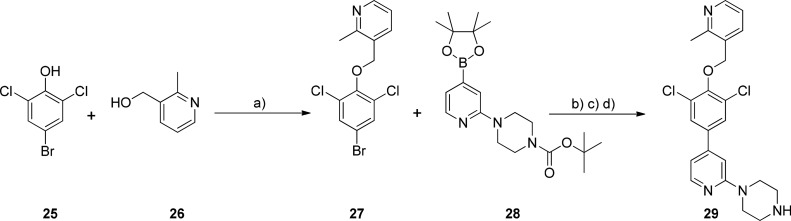

With the aim of increasing potency against TbNMT, the diphenyl piperidine ring was replaced with the dichlorophenyl-pyridyl-piperidine moiety of 1. This change reduced the logP by ∼1 log unit from 4.3 for 24, with an increase in PSA from 34 Å2 (19) to 50 Å2, which was within the acceptable guidance limits for BBB permeability32,33 to give 29 (synthesis shown in Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) polymer supported-PPh3, DIAD, alcohol, THF; (b) dioxane/1 M aq K3PO4, Pd(PPh3)4; (c) TFA, DCM; (d) 2 M HCl in diethyl ether.

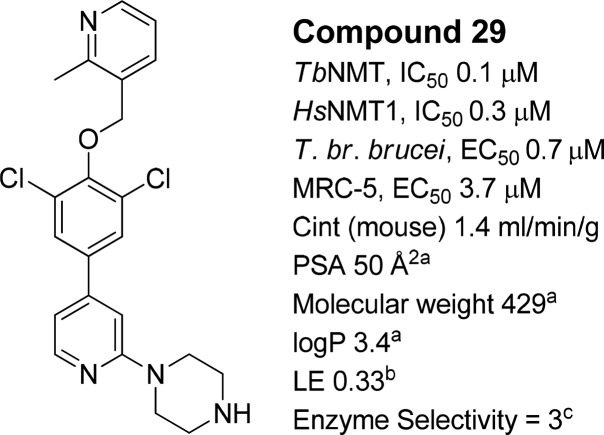

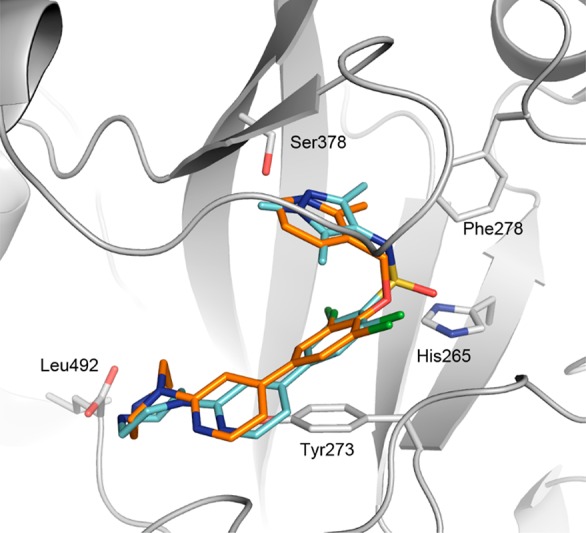

Compound 29 (Figure 5) exhibited a 4-fold improvement in potency against TbNMT (IC50 0.1 μM) and improved efficacy in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay (EC50 0.7 μM), while retaining good microsomal stability (1.4 mL/min/g) and LE (0.33). Encouragingly, 29 showed good levels of brain penetration (brain–blood = 0.4), a significant improvement over 1 (brain–blood < 0.1),22 indicating that the strategy of reducing MW and PSA was a valid approach (1, PSA 101 Å, MW 495). The crystal structure of 29 bound to AfNMT (Figure 6) was determined showing the ligand adopted a conformation similar to 1 with the biaryl system sitting in plane with the 2,6-dichlorophenyl ring stacking in plane with the side chain of Tyr273. Key interactions between the piperidine N to Ser378 and the piperazine to the C-terminal carboxyl group are retained from 24.

Figure 5.

Compound 29 profile. aValues calculated using the Optibrium STARDROP software. bLigand efficiency (LE), calculated as 0.6·ln(IC50)/(heavy atom count) using T. brucei NMT IC50 potency.25 IC50 values are shown as mean values of two or more determinations. Standard deviation was typically within 2-fold from the IC50. nd = not determined. cEnzyme selectivity calculated as HsNMT1 IC50 (μM)/TbNMT IC50 (μM).

Figure 6.

Binding mode of 29 (C atoms gold) bound to AfNMT (PDB 5T6C). Binding mode of 1 (C atoms cyan) is shown for comparison.

Replacement of the 2,6-Dichlorophenyl Ring

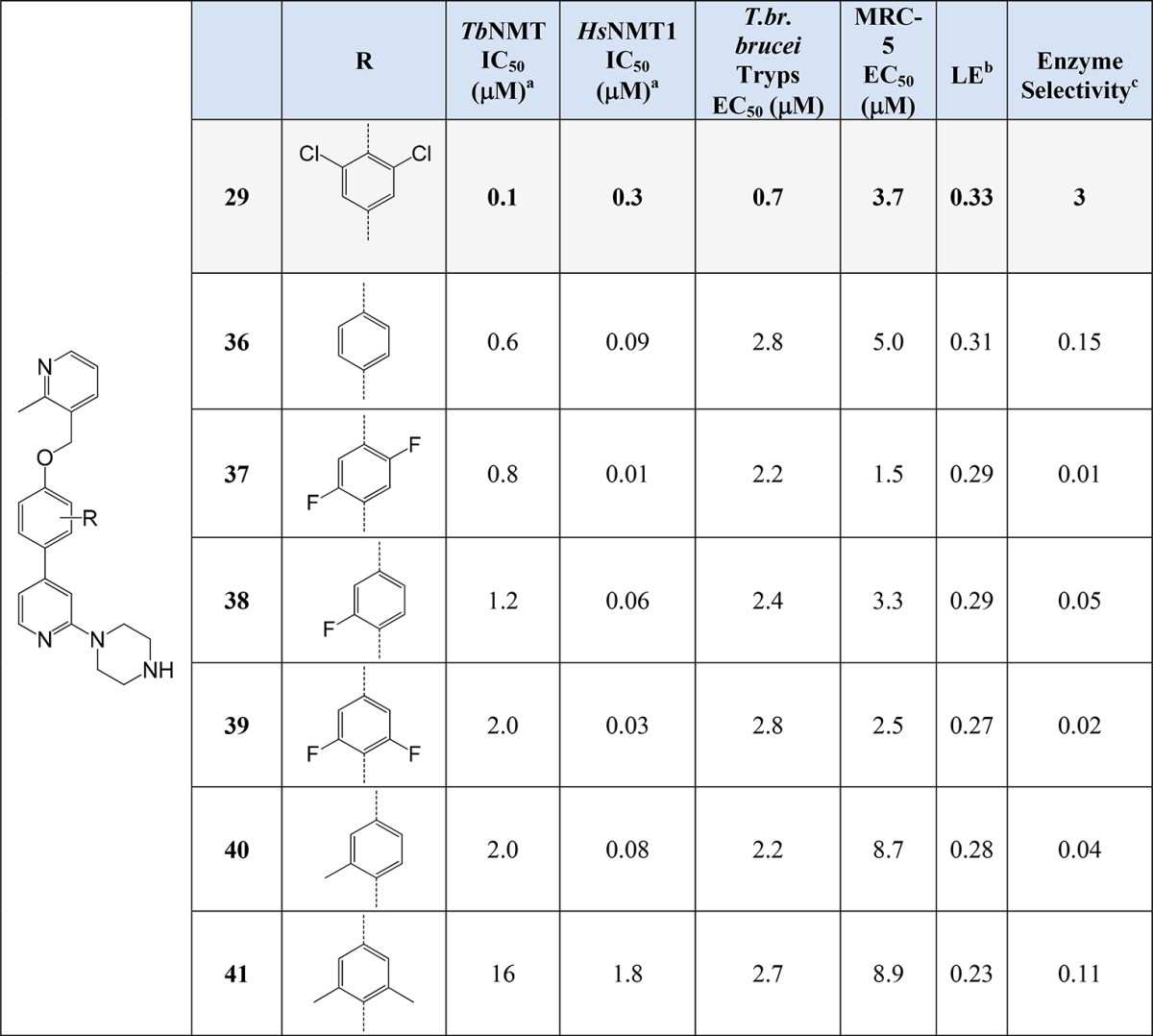

Optimization of 29 focused on modifications to the central 2,6-dichlorophenyl ring to increase enzymatic selectivity relative to HsNMT1 (0.3 μM, 3-fold compared to TbNMT IC50). These modifications were made employing the same chemistry as outlined in Scheme 1, by varying the starting substituted bromophenol used in the Mitsunobu step. These 2,6-dichlorophenyl modifications are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Modifications to the 2,6-Dichorophenyl Central Ring of Compound 29.

IC50 values are shown as mean values of two or more determinations. Standard deviation was typically within 2-fold from the IC50. nd = not determined.

Ligand efficiency (LE), calculated as 0.6·ln(IC50)/(heavy atom count) using T. brucei NMT IC50 potency.25

Enzyme selectivity calculated as HsNMT1 IC50 (μM)/TbNMT IC50 (μM).

None of the core modifications improved potency against TbNMT when compared to 29 (Table 2) nor LE and enzyme selectivity, although some demonstrated increased levels of potency against HsNMT1 (37, HsNMT1, IC50 0.01 μM). The reason for this increase in HsNMT1 activity was not explained using the available crystal structure data. Certainly inhibitors of human NMT such as 37 are of potential interest in the treatment of cancer,20 and further elaboration of the core could be explored.

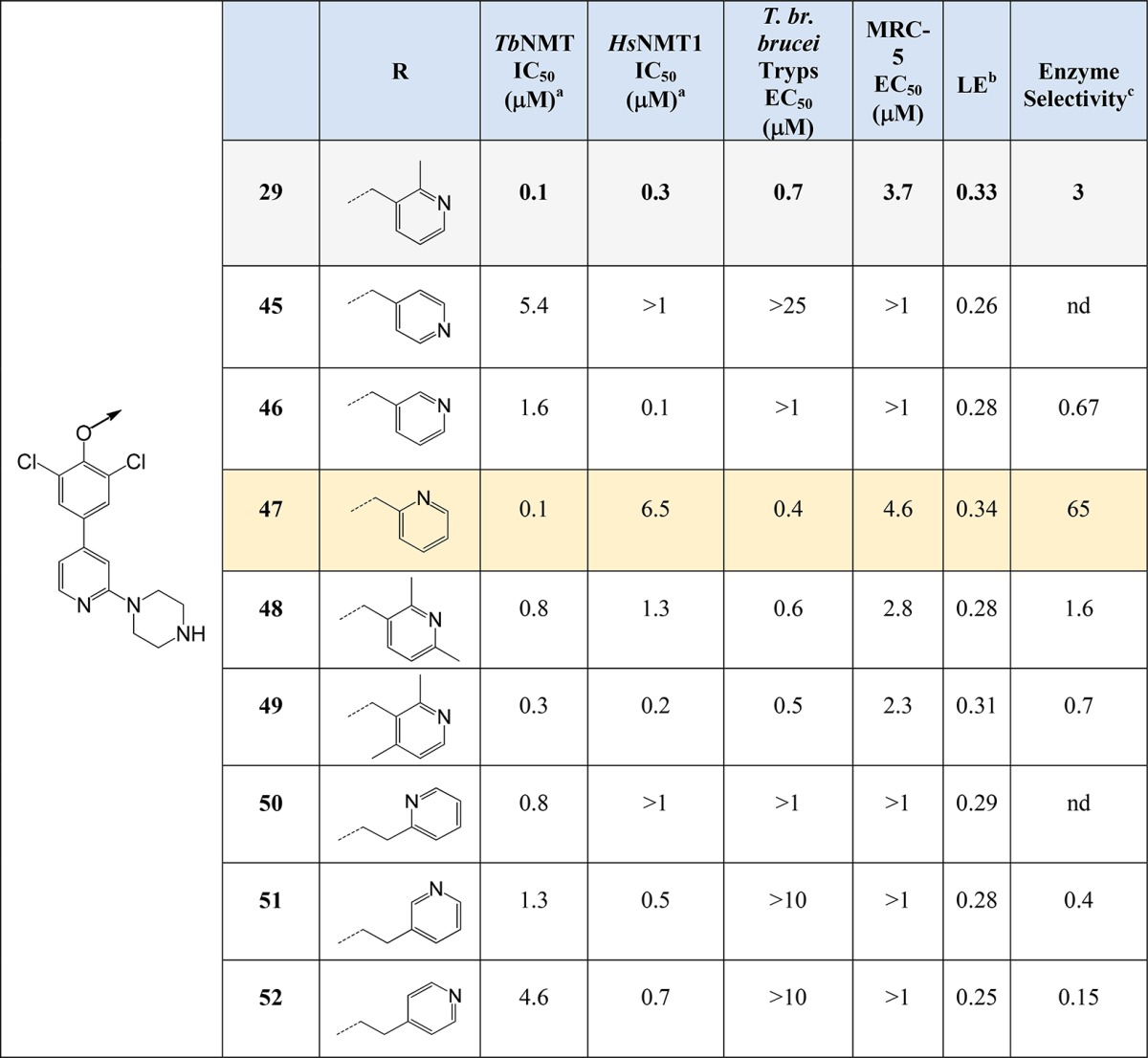

Pyridyl Headgroup SAR

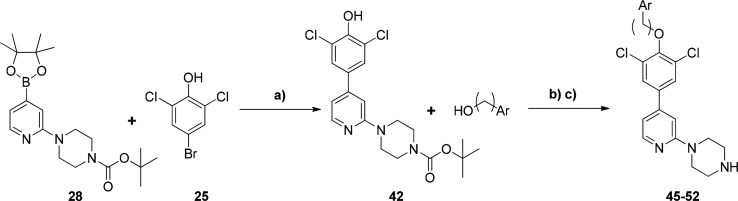

The next phase of optimization focused on modifications to the ether pyridyl ring of 29 shown in Table 3. These compounds were made using the same common phenol intermediate (Scheme 2), applying solid phase reagents such as polystyrene bound triphenylphosphine, and running reactions and purifications in parallel using commercially available alcohols or alcohols derived from commercially available carboxylic acids or esters after reduction with borane or lithium aluminum hydride (see Supporting Information).

Table 3. Pyridyl Head Group SAR of Compound 29.

IC50 values are shown as mean values of two or more determinations. Standard deviation was typically within 2-fold from the IC50. nd = not determined.

Ligand efficiency (LE), calculated as 0.6·ln(IC50)/(heavy atom count) using T. brucei NMT IC50 potency.25

Enzyme selectivity calculated as HsNMT1 IC50 (μM)/TbNMT IC50 (μM).

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Boc2O, NEt3, THF; (b) 4-bromo-2,6-dichlorophenol, MeCN/1 M aq K3PO4, Pd(dppf)2Cl2; (c) PS–PPh3, DIAD, alcohol, THF; (d) TFA, DCM.

Modifications to the pyridyl headgroup showed encouraging results with 47 equipotent to 29 (IC50 ≈ 0.1 μM) but with ∼65-fold selectivity over HsNMT1, equivalent activity in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay, and promising microsomal stability (Cint 4.2 mL/min/g). Compound 30, though, had equivalent activity to 29 in the MRC-5 counter screen, indicating that HsNMT1 activity may not have been driving the MRC-5 toxicity.

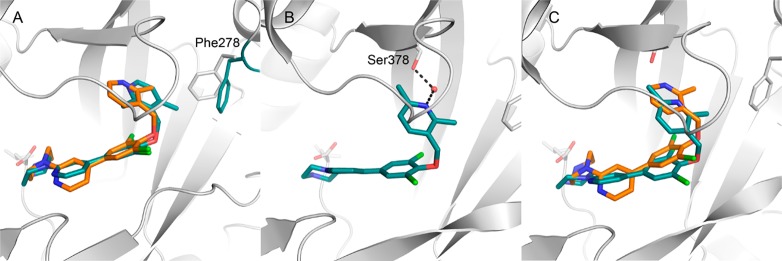

Homologation of the linker to the pyridyl group did not improve potency, as did groups on the pyridyl ring at the 6- (48) or 4-positions (49), though both 48 and 49 showed equivalent activity in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay to 29. The crystal structure of 29 overlaid with the trimethylpyrazole of 1 suggested that additions of methyl substitution may have been beneficial to potency (Figure 7A) because the trimethyl substitution of pyrrole in 1 was essential for activity. Subsequent crystal structures of 48 showed that the binding pocket the pyridyl headgroup accesses is small and that these substituents in the case of 49 forced the ether pyridyl ring to twist in the pocket to avoid steric clashes with its dichlorophenyl ring, and for 48, the 4-methyl forces the pyridyl ring out of the pocket. In both cases, the direct hydrogen bond from the pyridyl nitrogen to the serine was broken, but 48 still formed an interaction, though this was now water mediated (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Binding mode of pyridyl headgroup modifications. (A) Binding mode of 49 (C atoms aquamarine; PDB 5T6H) compared with 29 (C atoms gold). The side chain of Phe278 rotates to accommodate the 4-methyl group. (B) Binding mode of 48 (C atoms aquamarine; PDB 5T6E); the interaction with Ser378 is now a water bridged interaction. (C) Compound 48 compared with 29.

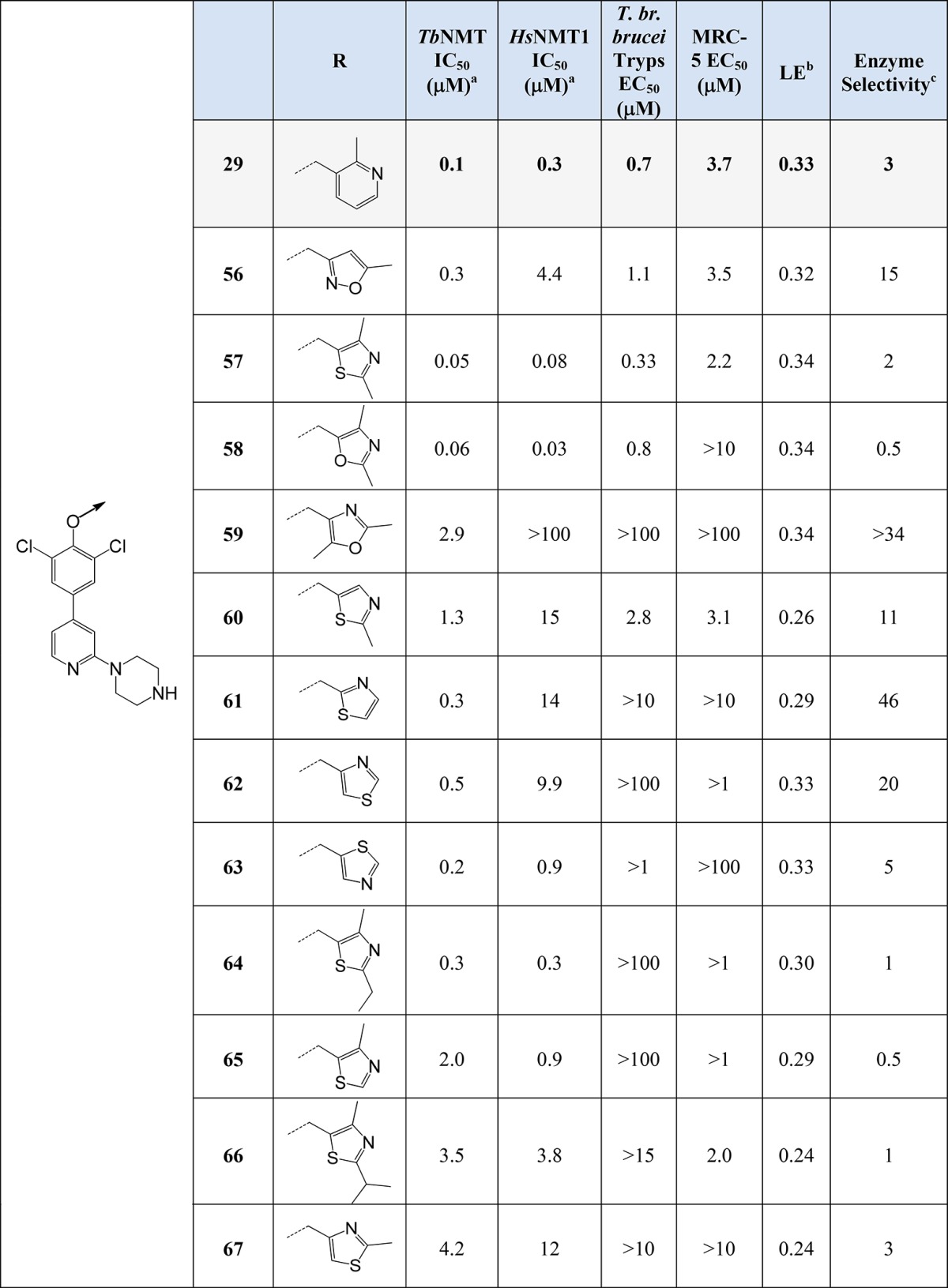

Alternative Nonpyridyl Head Group SARs

To advance the series, two regions within the structure were modified with the aim to improve potency, first examining pyridyl replacements and modifications to the pyridyl ring and replacement of the piperazino-pyridine moiety. First, the pyridyl ring was replaced with a range of five-membered heterocycles, mainly thiazoles, with various substitutions; see Table 4. The most potent of these showed levels of promising activity against TbNMT (IC50 ≈ 0.05–0.06 μM; 58 and 57). The SAR around 57 was tight. The removal of either methyl groups (60 and 65) lost activity against TbNMT; in addition, substitution of the 2-methyl group with either ethyl (64) or isopropyl (66) lost all activity in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay. Compound 57 showed good stability to microsomal turnover (Cint 2.4 mL/min/g) but also improved selectivity over MRC-5 cytotoxicity. Both 58 and 57 showed equivalent levels of potency against HsNMT1 (IC50 ≈ 0.03–0.08 μM) and again showed very different MRC-5 activities, indicating that MRC-5 toxicity may not be entirely driven by HsNMT1 activity.

Table 4. Pyridyl Head Group Replacements.

IC50 values are shown as mean values of two or more determinations. Standard deviation was typically within 2-fold from the IC50. nd = not determined.

Ligand efficiency (LE), calculated as 0.6·ln(IC50)/(heavy atom count) using T. brucei NMT IC50 potency.25

Enzyme selectivity calculated as HsNMT1 IC50 (μM)/TbNMT IC50 (μM).

Replacement of the Piperazino-Pyridine Moiety

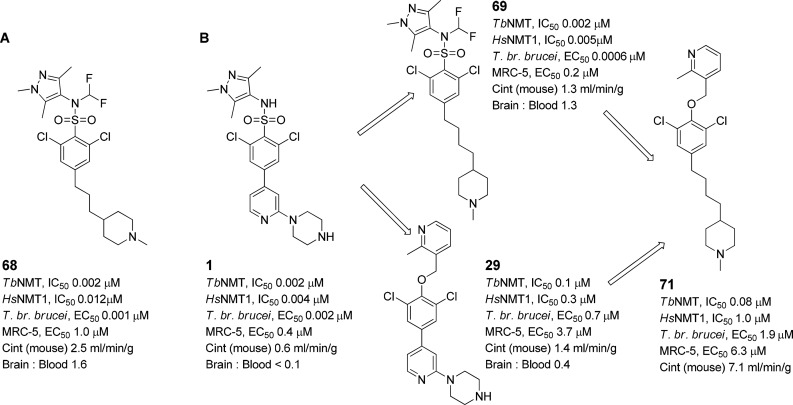

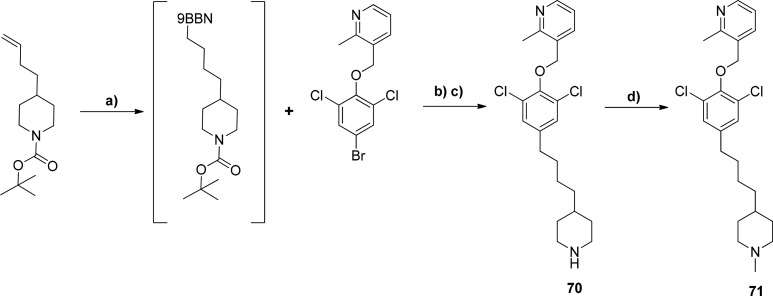

We had previously validated TbNMT as a druggable target in the stage 2 model for HAT in mice using 68 as a model compound (Figure 8A).24 Compound 68 showed good potency in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay at EC50 0.001 μM and improved levels of selectivity over MRC-5 cells when compared to 1. We examined hybridizing the 4-C chain derivative of 68, 69, which showed equally good efficacy and potency, and 29 to increase efficacy in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay. Compound 71 (synthesis in Scheme 3) showed increased selectivity over MRC-5 cells and HsNMT1 but showed a significant drop off in efficacy in the T. br. brucei proliferation assay. This was potentially caused by the significant increase in lipophilicity of 71 (logP 5.5) compared to 29 (logP 3.4), resulting in an increased level of nonspecific protein/membrane binding. Given the more favorable logP of 29, further optimization focused on derivatives of 29 rather than 71. Compound 70 (Scheme 3), the NH piperidine of 71, showed no in vitro activity against TbNMT.

Figure 8.

Hybridization approach.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 9-BBN, THF; (b) Pd(PPh3), K3PO4, H2O, DMF; (c) TFA, DCM; (d) CH2O, Na(OAc3)3BH, CHCl3.

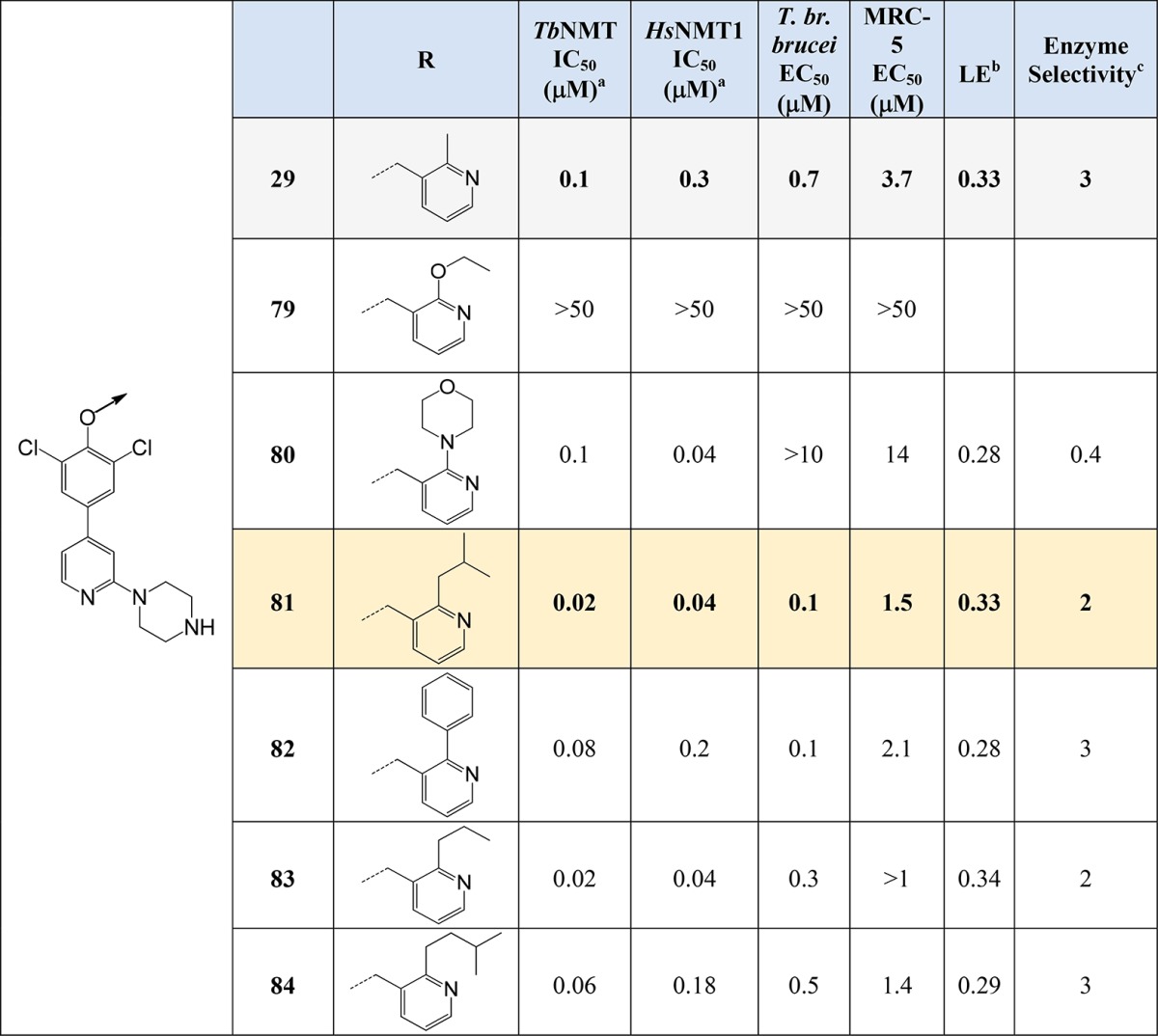

Pyridyl Headgroup Optimization

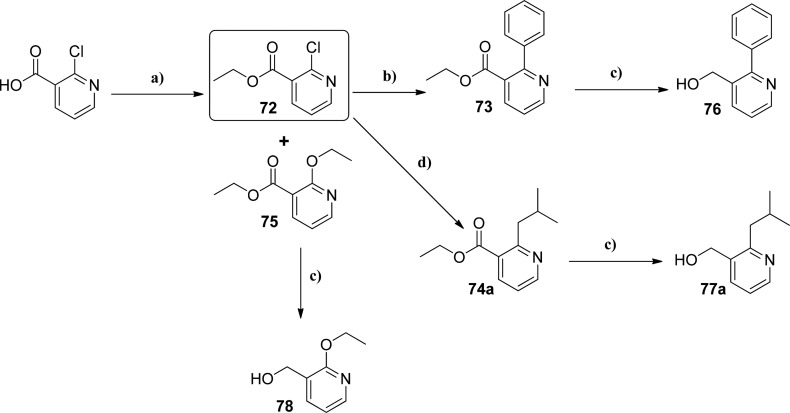

The crystal structure of 29 (Figure 6) indicated that the methyl substituent on the pyridyl ring was pointing into a small pocket. Chemistry was developed to explore this pocket with various hydrophobic and polar groups as detailed in Scheme 4. Using a common intermediate (ethyl 2-chloronicotinate, 72), Suzuki and Negishi reactions were used to install aromatics rings (73) and alkyl groups (74a–c), respectively. Amines were installed through displacement of the chlorine of 72. After reduction of the ethyl esters (73–75) to the corresponding alcohols (76–78), they were reacted using standard Mitsunobu conditions (Scheme 2) to give final products detailed in Table 5.

Scheme 4.

Reagents and conditions: (a) H2SO4, EtOH; (b) phenylboronic acid, 1 M K3PO4/dioxane, Pd(PPh3)4; (c) 2 M LiAlH4 in THF, 0 °C; (d) Pd(tBuP)2, 0.5 M isobutylzinc bromide, anhydrous THF.

Table 5. Pyridyl Substitutions.

IC50 values are shown as mean values of two or more determinations. Standard deviation was typically within 2-fold from the IC50. nd = not determined.

Ligand efficiency (LE), calculated as 0.6·ln(IC50)/(heavy atom count) using T. brucei NMT IC50 potency.25

Enzyme selectivity calculated as HsNMT1 IC50 (μM)/TbNMT IC50 (μM).

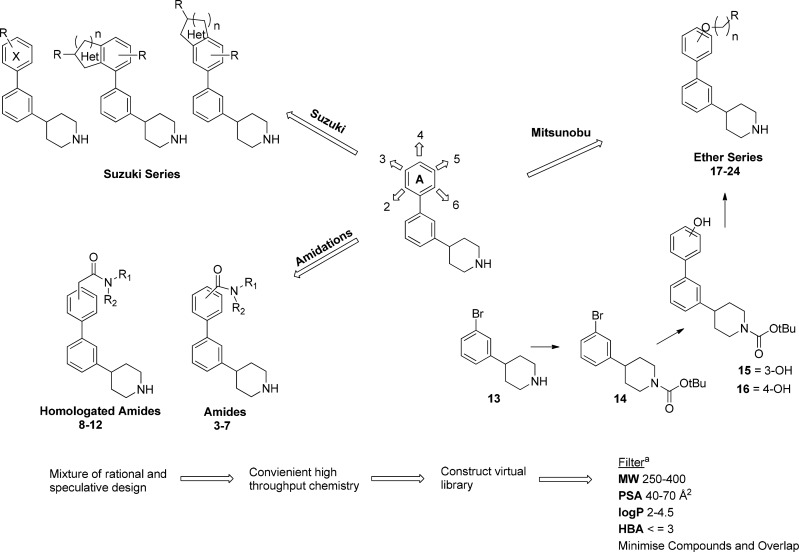

Good levels of inhibition of TbNMT were observed for all compounds prepared (except 79), some with improved potency over 29. The loss of activity of 79 was most probably caused by the alkoxy-group reducing the basicity of the pyridine ring, making the ring nitrogen a poorer HBA. Compounds 81 and 82 showed promising potency against the parasite (EC50 = 0.1 μM), with good selectivity compared to MRC-5 cells (81), and had good microsomal stability (81, 1.2 mL/min/mg; 82, 1.6 mL/min/mg). Compound 81 (Figure 9) showed significant levels of brain penetration (brain–blood ratio = 1.9), a significant improvement on 29 (brain–blood ratio 0.4) and 1 (brain–blood ratio < 0.1). Compound 81 represents a good lead for further optimization to identify development candidates for stage 2 HAT.

Figure 9.

Comparison of 1 and 81.

Conclusions

By using 1 as a starting point to identify alternative TbNMT inhibitor scaffolds with physicochemical properties suitable for penetration into the brain to treat stage 2 HAT, we identified an ether linker as a replacement of the sulfonamide of 1. This modification reduced molecular weight and polar surface area, producing a viable alternative series with excellent levels of brain penetration. This work highlights the importance of decreasing the PSA as a way of increasing the probability of brain penetration. Further optimization identified compounds with good levels of TbNMT and T. br. brucei antiproliferative activity and microsomal stability. Though in comparison with the original structure 1, further potency gains against the enzyme and in the parasite proliferation assay are required. This series presents good leads to identify potential development candidates for stage 2 HAT.

Experimental Section

Synthetic Materials and Methods

Chemicals and solvents were purchased from the Aldrich Chemical Co., Fluka, ABCR, VWR, Acros, Fisher Chemicals, and Alfa Aesar and were used as received unless otherwise stated. Air- and moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out under an inert atmosphere of argon in oven-dried glassware. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on precoated TLC plates (layer 0.20 mm silica gel 60 with fluorescent indicator UV254, from Merck). Developed plates were air-dried and analyzed under a UV lamp (UV254/365 nm). Flash column chromatography was performed using prepacked silica gel cartridges (230–400 mesh, 40–63 μm, from SiliCycle) using a Teledyne Presearch ISCO Combiflash Companion 4X or Combiflash Retrieve. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance II 500 spectrometer (1H at 500.1 MHz, 13C at 125.8 MHz) or a Bruker DPX300 spectrometer (1H at 300.1 MHz). Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in ppm recorded using the residual solvent as the internal reference in all cases. Signal splitting patterns are described as singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), quartet (q), pentet (p), multiplet (m), broad (br), or a combination thereof. Coupling constants (J) are quoted to the nearest 0.1 Hz. LC–MS analyses were performed with either an Agilent HPLC 1100 series connected to a Bruker Daltonics micrOTOF or an Agilent Technologies 1200 series HPLC connected to an Agilent Technologies 6130 quadrupole LC–MS, where both instruments were connected to an Agilent diode array detector. LC–MS chromatographic separations were conducted with a Waters Xbridge C18 column, 50 mm × 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm particle size; mobile phase, water/acetonitrile + 0.1% HCOOH, or water/acetonitrile + 0.1% NH3; linear gradient 80:20 to 5:95 over 3.5 min, and then held for 1.5 min; flow rate 0.5 mL min–1. All assay compounds had a measured purity of ≥95% (by TIC and UV) as determined using this analytical LC–MS system; a lower purity level is indicated. High-resolution electrospray measurements were performed on a Bruker Daltonics MicrOTOF mass spectrometer. Microwave-assisted chemistry was performed using a Biotage Initiator Microwave Synthesizer.

tert-Butyl-4-(3-Bromophenyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (14)

A solution of 4-(3-bromophenyl)piperidine·hydrochloride (13) (5.1 g, 18.4 mmol, 1 equiv), Boc2O (4.4 g, 20.2 mmol, 1.1 equiv), and triethylamine (3.87 mL, 27.8 mmol, 1.5 equiv) in THF (50 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The reaction was filtered, and the filtrate was washed with dilute 10% citric acid and extracted into ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate layer was washed with water, then dried over MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated to give an off-white solid (14) (6.13 g, 98% yield). 1H NMR, 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ1.51 (s, 9H), 1.57–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.81–1.86 (m, 2H), 2.64 (tt, J = 3.70, 12.21, 1H), 2.77–2.85 (m, 2H), 4.22–4.32 (m, 2H), 7.14–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.39 (m, 2H). [M + H]+ = 388.4.

tert-Butyl 4-(3′-Hydroxy-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (15)

tert-Butyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (14) (2 g, 5.88 mmol, 1 equiv), 3-hydroxyphenyl boronic acid (974 mg 7.06 mmol, 1.2 equiv), anhydrous dioxane (10 mL), and 1 M aq K3PO4 (6 mL) were combined in a microwave vessel and argon bubbled through the mixture for 5 min. Pd(PPh3)4 (136 mg, 0.118 mmol, 2%), was added, and the reaction was degassed again for a further 5 min before microwaving at 140 °C for 15 min. The resulting solution was extracted into dichloromethane, washed with sat. aq NaHCO3, and passed through a phase separation cartridge. The organic layer was then absorbed onto silica and purified by flash column chromatography running a gradient from 0% ethyl acetate/hexane to 50% ethyl acetate/hexane to give 15 as a colorless oil (1.76 g, 85% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.53 (s, 9H), 1.60–1.76 (m, 2H), 1.83–1.91 (m, 2H), 2.71 (tt, J = 3.68, 12.33, 1H), 2.70–2.91 (m, 2H), 4.24–4.35 (m, 2H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 6.88 (dd, J = 2.50, 8.11, 1H), 7.10–7.20 (m, 3H), 7.28–7.46 (m, 4H).

tert-Butyl 4-(4′-Hydroxy-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (16)

A mixture of 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid (183 mg, 1.32 mmol, 1 equiv), tert-butyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (14) (450 mg, 1.32 mmol, 1 equiv), Pd(PPh3)4 (30 mg), and K3PO4 (1 equiv) in DMF–H2O (3:1, 4 mL) afforded 16 (326 mg, 70% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO, δ 1.56 (s, 9H), 1.68–1.74 (m, 2H), 1.86–1.96 (m, 2H), 2.72–2.80 (m, 1H), 2.80–3.00 (m, 2H), 4.29–4.32 (br. s, 2H), 5.02 (s, 1H), 6.96–6.99 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.39–7.48 (m, 3H), 7.52–7.56 (m, 2H). [M + H]+ = 354.2331, 298.1651 (product – tBu).

4-(3′-((1,3,5-Trimethyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methoxy)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)piperidine (17)

tert-Butyl 4-(3′-hydroxy-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (15) (100 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv), (1,3,5-trimethylpyrazole)methanol (44 mg, 0.31 mmol, 1.1 equiv), polystyrene bound-PPh3 (PPh3 = triphenylphosphine, 1.84 mmol/g loading, 228 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD, 66 μL, 0.34 mmol, 1.2 equiv) in anhydrous dioxane (5 mL) in a capped test tube was heated at 60 °C for 16 h. The reaction was absorbed onto silica and purified by flash column chromatography running a gradient from 0% ethyl acetate/hexane to 100% ethyl acetate. The resulting product was evaporated in vacuo before dissolving in dichloromethane (10 mL), addition of trifluoroacetic acid (10 equiv) and stirring at RT for 3 h. The reaction was then evaporated in vacuo before dissolving in dichloromethane and loading onto a prewashed SCX cartridge. The SCX cartridge was washed with dichloromethane (3 × 10 mL) and MeOH (3 × 10 mL) before eluting the product with 7 N ammonia in methanol. This was evaporated to give 17 (64 mg, 61% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.67–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.87–1.92 (m, 2H), 2.70–2.77 (m, 1H), 2.80–2.89 (m, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 4.22–4.35 (m, 2H), 4.90 (s, 2H), 6.39 (br. s, 1H), 6.98–7.01 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.23 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.47 (m, 4H). [M + H] = 427.2.

Compounds 14–20 were made in an analogous manner to 17 from 16, see Supporting Information for analytical data.

Prototypical Mitsunobu Reaction of a Pyridyl Alcohol and a Substituted Phenol (Scheme 1)

See Supporting Information for the synthesis of intermediates 30–35 for compounds 36–41 (Table 2).

3-((4-Bromo-2,6-dichlorophenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (27)

DIAD (diisopropyl azodicarboxylate, 5 mL, 24.8 mmol, 1.2 equiv) was added to a suspension of 4-bromo-2,6-dichlorophenol (25) (5.0 g, 20.7 mmol, 1 equiv), 2-methyl-3-hydroxymethylpyridine (26) (3.1 g, 24.8 mmol, 1.2 equiv), and polystyrene bound-PPh3 (1.84 mmol/g loading, 16.2 g, 29.8 mmol, 1.2 equiv) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) then heated at 70 °C for 4 h. After cooling, the reaction mixture was filtered, the beads washed with MeOH and dichloromethane, and the filtrate concentrated in vacuo. The resulting residue was triturated with MeOH to give 27 as a white solid (5.46 g, 76% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.68 (s, 3H), 5.03 (s, 2H), 7.18 (dd, J = 4.90, 7.68 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (s, 3H), 7.82 (dd, J = 1.68, 7.68 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (dd, J = 1.68, 4.90 Hz, 1H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 347.9.

tert-Butyl 4-(4-(4,4,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carboxylate (28)

A solution of 1-(4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (2.97 g, 10.27 mmol, 1 equiv), di-tert-butyl-dicarbonate (Boc2O, 2.5 g, 11.3 mmol, 1.1 equiv), in THF (20 mL) and triethylamine (2.1 mL, 15.4 mmol, 1.5 equiv) was stirred at RT overnight. The resulting reaction was extracted into dichloromethane, and then washed with 10% citric acid and then water. The dichloromethane layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered and evaporated to give (28) as a white solid (4 g, 100% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.28 (s, 12H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 3.45–3.50 (m, 8H), 6.90 (d, J = 4.91, 1H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 8.14 (dd, J = 1.02, 4.89, 1H). [M + H]+ = 389.45.

Prototypical Suzuki Reaction of an Aryl Bromide and a Boronate Ester (Compounds 29–35)

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2-methylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine Dihydrochloride Salt (29)

tert-Butyl 4-(4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carboxylate (28) (67 mg, 0.23 mmol, 1 equiv), 3-((4-bromo-2,6-dichlorophenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (27) (80 mg, 0.23 mmol, 1 equiv), and potassium phosphate·trihydrate (49 mg, 0.231 mmol, 1 equiv) in DMF–H2O (1:1, 4 mL) was combined in a microwave vessel and degassed with argon for 5 min, before the addition of Pd(PPh3)4 (14 mg, 0.012 mmol, 5%), and reaction degassed again, then microwaved at 100 °C for 40 min. Reaction was concentrated in vacuo, extracted into dichloromethane, and then washed with aq NaHCO3. The two-phase system was passed through a phase separation cartridge, the filtrate concentrated in vacuo, and the title compound purified by flash column chromatography using 8% MeOH/ethyl acetate + 1% aq NH3 as the eluent. The residue was taken up in dichloromethane, ethereal HCl was added (2 M, 2 mL) and concentrated, and the dihydrochloride salt of 29 was triturated with ether, filtered, and washed with ether (104 mg, 71% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, d6-DMSO δ 2.82 (s, 3H), 3.17–3.23 (m, 4H), 3.85–3.90 (m, 4H), 5.29 (s, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 5.20 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.30 (m, 1H), 7.78–7.86 (m, 1H), 8.06 (s, 2H), 8.22 (d, J = 5.20 Hz, 1H), 8.41–8.51 (m, 1H), 8.71–8.77 (m, 1H), 9.15 (br s, 2H). HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H23Cl2N4O1 = 429.1243, found = 429.1240.

1-(4-(4-((2-Methylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine Dihydrochloride Salt (36)

Prepared from 3-((4-bromophenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (30) (150 mg, 0.54 mmol, 1 equiv) and 1-(4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine 28 (156 mg, 0.54 mmol, 1 equiv), according to the method outlined for the synthesis of 29, to give 36 as a dihydrochloride salt (150 mg, 64% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO δ 2.79 (s, 2H), 3.21–3.27 (m, 4H), 3.93–3.98 (m, 4H), 5.40 (s, 2H), 7.21–7.30 (m, 3H), 7.35–7.43 (m, 1H), 7.86–7.95 (m, 3H), 8.15 (d, J = 6.00 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 7.45 Hz, 1H), 8.74 (d, J = 5.75 Hz, 1H), 9.39 (br s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 361.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H25N4O1 = 361.2023, found = 361.2033.

1-(4-(2,5-Difluoro-4-((2-methylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine Dihydrochloride (37)

Prepared from 3-((4-bromo-2,5-difluorophenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (31) (106 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv) and 28 (98 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv), according to the method outlined for the synthesis of 29, to give 37 as a dihydrochloride salt (124 mg, 78% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO δ 2.79 (s, 3H), 3.17–3.23 (m, 4H), 3.84–3.90 (m, 4H), 5.48 (s, 2H), 6.99–7.03 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.20, 12.20 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 7.33, 11.83 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (t, J = 7.90 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 5.55 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 7.25 Hz, 1H), 8.76 (d, J = 5.65 Hz, 1H), 9.32 (br s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 397.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H23F2N4O1 = 397.1834, found = 397.1848.

1-(4-(2-Fluoro-4-((2-methylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine Dihydrochloride (38)

Prepared from 3-((4-bromo-3-fluorophenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (32) (100 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv) and 28 (98 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv), according to the method outlined for the synthesis of 29, to give 38 as a dihydrochloride salt (110 mg, 72% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO δ 2.81 (s, 3H), 3.19–3.25 (m, 4H), 3.89–3.96 (m, 4H), 5.42 (s, 2H), 7.02–7.08 (m, 1H), 7.13 (dd, J = 1.85, 8.35 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (dd, J = 1.63, 12.88 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (t, J = 8.65 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (t, J = 6.48 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 5.65 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (d, J = 7.65 Hz, 1H), 8.75 (d, J = 5.05 Hz, 1H), 9.47 (br s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 379.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H24F1N4O1 = 379.1929, found = 379.1942.

1-(4-(2,6-Difluoro-4-((2-methylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine Dihydrochloride (39)

Prepared from 3-((4-bromo-3,5-difluorophenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (33) (106 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv) and 28 (98 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1 equiv), according to the method outlined for the synthesis of 29, to give 39 as a dihydrochloride salt (109 mg, 69% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO δ 2.77 (s, 3H), 3.16–3.21 (m, 4H), 3.77–3.82 (m, 4H), 5.40 (s, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 4.95 Hz, 1H), 7.03–7.07 (m, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 9.90 Hz, 2H), 7.86–7.91 (m, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 5.20 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 6.30 Hz, 1H), 8.75 (d, J = 5.45 Hz, 1H), 9.20 (br s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 397.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H23F2N4O1 = 397.1834, found = 397.1852.

1-(4-(2-Methyl-4-((2-methylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine Dihydrochloride (40)

Prepared from 3-((4-bromo-3-methylphenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (34) (150 mg, 0.51 mmol, 1 equiv) and 28 (148 mg, 0.51 mmol, 1 equiv), according to the method outlined for the synthesis of 29, to give 40 as a dihydrochloride salt (110 mg, 48% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO δ 2.29 (s, 3H), 2.77 (s, 3H), 3.17–3.23 (m, 4H), 3.83–3.88 (m, 4H), 5.34 (s, 2H), 6.80–6.84 (m, 1H), 6.96–7.00 (m, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 2.58, 8.43 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 2.50 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.45 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (t, J = 6.63 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 5.80 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 7.25 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (d, J = 5.20 Hz, 1H), 9.27 (br s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 375.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C23H27N4O1 = 375.2179, found = 375.2191.

1-(4-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-((2-methylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine Dihydrochloride (41)

Prepared from 3-((4-bromo-3,5-dimethylphenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (35) (150 mg, 0.49 mmol, 1 equiv) and 28 (142 mg, 0.49 mmol, 1 equiv), according to the method outlined for the synthesis of 29, to give 41 as a dihydrochloride salt (177 mg, 75% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO δ 2.033 (s, 6H), 2.79 (s, 3H), 3.17–3.23 (m, 4H), 3.84–3.89 (m, 4H), 5.31 (s, 2H), 6.63–6.67 (m, 1H), 6.89–6.93 (m, 3H), 7.89 (t, J = 6.70 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 5.35 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (d, J = 7.70 Hz, 1H), 8.73 (dd, J = 1.10, 5.65 Hz, 1H), 9.36 (br s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 389.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C24H29N4O1 = 389.2336, found = 389.235.

tert-Butyl 4-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carboxylate (42)

A solution of a tert-butyl 4-(4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carboxylate 28 (2.0 g, 5.14 mmol, 1.2 equiv), and 4-bromo-2,6-dichlorophenol (25) (1.04 g, 4.3 mmol, 1 equiv) in acetonitrile (7 mL) and aq 1 M K3PO4 (5 mL) was degassed by bubbling argon through for 5 min; then Pd(dppf)2Cl2 (175 mg, 0.22 mmol, 5%) was added and the reaction degassed again for a further 5 min before microwaving at 100 °C for 30 min. The cooled solution was diluted with dichloromethane and washed with aq NaHCO3, the dichloromethane layer was dried over MgSO4, and the filtrate was evaporated onto silica and purified by flash column chromatography running a gradient from 0% ethyl acetate/hexane to 50% ethyl acetate/hexane to give 42 as a white solid (1.07 g, 49% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.52 (s, 9H), 3.58–3.64 (m, 8H), 6.05 (br. s, 1H), 6.72 (s, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 5.30, 1H), 7.53 (s, 2H), 8.25 (d, J = 5.19, 1H). [M + H]+ = 424.2.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-(2-(pyridin-3-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (51)

Diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD, 61 μL, 0.31 mmol, 1.1 equiv) was added to a suspension of 2-(pyridin-3-yl)ethanol (42 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.2 equiv), polystyrene bound-PPh3 (1.84 mmol/g loading, 200 mg, 0.37 mmol, 1.2 equiv), and 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) and then heated at 70 °C for 4 h. After cooling, the reaction mixture was filtered, the beads washed with MeOH and dichloromethane, and the filtrate absorbed onto silica and purified by flash column chromatography running a gradient from 0% ethyl acetate/hexane to 100% ethyl acetate. The resulting residue was dissolved in dichloromethane (10 mL), trifluoroacetic acid (10 equiv) was added, and the reaction was stirred at RT for 16 h. The reaction was evaporated in vacuo before loading onto a prewashed SCX cartridge. The cartridge was washed with dichloromethane (3 × 10 mL) and MeOH (3 × 10 mL) before eluting with 7 N ammonia in methanol. This was absorbed onto silica and purified by flash column chromatography running a gradient from 0% MeOH/dichloromethane + 1% NH3 to 20% MeOH/dichloromethane + 1% NH3 to give 51 as a white solid (35 mg, 29% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.02–3.05 (m, 4H), 3.22 (t, J = 6.90 Hz, 2H), 3.58–3.61 (m, 4H), 4.30 (t, J = 6.90 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 1.50, 5.25 Hz, 1H), 7.28–7.31 (m, 1H), 7.52 (s, 2H), 7.72–7.74 (m, 1H), 8.25 (dd, J = 0.61, 5.24 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (dd, J = 1.61, 4.97 Hz, 1H), 8.63 (d, J = 2.11 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 429.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H23Cl2N4O1 = 429.1243, found = 429.1245.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-(pyridin-4-ylmethoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (45)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and pyridin-4-ylmethanol (37 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 45 as an off-white solid (1 mg, 1% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.04–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.61–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 1.52, 5.39 Hz, 1H), 7.52–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.58 (s, 2H), 8.28 (d, J = 5.25 Hz, 1H), 8.69 (dd, J = 1.80, 5.94 Hz, 2H). [M + H]+ = 415.1.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-(pyridin-3-ylmethoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (46)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and pyridin-3-ylmethanol (33 μL, 0.34 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 46 as an off-white solid (17 mg, 15% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.06–3.11 (m, 4H), 3.63–3.67 (m, 4H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 7.37–7.41 (m, 1H), 7.55–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.96–7.99 (m, 1H), 8.26–8.28 (m, 1H), 8.64–8.67 (m, 1H), 8.77–8.80 (m, 1H). [M + H]+ = 415.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C21H21Cl2N4O1 = 415.1087, found = 415.1079.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-(pyridin-2-ylmethoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (47)

Prepared using 42 (186 mg, 0.44 mmol, 1 equiv) and pyridin-2-ylmethanol (58 mg, 0.53 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 47 as an off-white solid (130 mg, 71% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.04–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 6.74 (d, J = 5.29 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (s, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 1.26 Hz, 2H), 7.30–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.80–7.86 (m, 2H), 8.27 (d, J = 5.25 Hz, 1H), 8.63 (d, J = 4.30 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 415.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C21H21Cl2N4O1 = 415.1087, found = 415.1088.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2,6-dimethylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (48)

Prepared using 42 (200 mg, 0.44 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2,6-dimethylpyridin-3-yl)methanol (43) (for synthesis see Supporting Information) (78 mg, 0.57 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 48 as an off-white solid (130 mg, 63% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.59 (s, 3H), 2.72 (s, 3H), 3.0–3.07 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 5.27 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 7.81 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 7.81 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 5.16 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 443.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C23H25Cl2N4O1 = 443.14, found = 443.1402.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2,4-dimethylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine) (49)

Prepared using 42 (112 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2,6-dimethylpyridin-4-yl)methanol (44) (for synthesis see Supporting Information) (44 mg, 0.32 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 49 as an off-white solid (56 mg, 49% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, DMSO δ 2.44 (s, 3H), 2.68 (s, 3H), 2.93–2.99 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.68 (m, 4H), 5.24 (s, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 5.20 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.96 (s, 2H), 8.16 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 5.13 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 443.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C23H25Cl2N4O1 = 443.1400, found = 443.1392.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-(2-(pyridin-2-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (50)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)pyridine (38 μL, 0.34 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 50 as an off-white solid (24 mg, 20% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.02–3.05 (m, 4H), 3.39 (t, J = 6.75 Hz, 2H), 3.58–3.61 (m, 4H), 4.49 (t, J = 6.65 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 1.50 Hz, 5.25, 1H), 7.18–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (s, 2H), 7.65–7.69 (m, 1H), 8.25 (dd, J = 0.64, 5.25 Hz, 1H), 8.58–8.60 (m, 1H). [M + H]+ = 429.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H23Cl2N4O1 = 429.1243, found = 429.1231.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-(2-(pyridin-4-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine) (52)

Prepared using 42 (112 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)pyridine (42 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.2eq) according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 52 as an off-white solid (22 mg, 18% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.02–3.05 (m, 4H), 3.22 (t, J = 6.68 Hz, 2H), 3.58–3.61 (m, 4H), 4.33 (t, J = 6.68 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 1.44 Hz, 5.25, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 1.59, 5.96 Hz, 2H), 7.53 (s, 2H), 8.25 (dd, J = 0.57, 5.19 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (dd, J = 1.54, 4.22 Hz, 2H). [M + H]+ = 429.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H23Cl2N4O1 = 429.123956, found = 429.123956.

Compounds 56–67 were synthesized using the standard Mitsunobu coupling conditions followed by BOC deprotection using TFA from 42 according to the procedure outlined in the synthesis of 51 or, in the case of 56, using the methodology used for compound 29.

3-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-5-methylisoxazole Dihydrochloride (56)

4-Bromo-2,6-dichlorophenol (500 mg, 2.07 mmol, 1 equiv) and (5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)methanol (351 mg, 3.10 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were reacted according to the method outlined for 27 to give 3-((4-bromo-2,6-dichlorophenoxy)methyl)-5-methylisoxazole as a white solid (348 mg, 50% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.46 (d, J = 0.85 Hz, 3H), 5.08 (s, 2H), 6.28–6.29 (m, 1H), 7.48 (s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 337.9.

3-((4-Bromo-2,6-dichlorophenoxy)methyl)-5-methylisoxazole (100 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1 equiv) and 28 (86 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1 equiv) were reacted according to the method outlined for the synthesis of 29 to give 56 as a dihydrochloride salt (104 mg, 71% yield). 1H NMR 300 MHz, DMSO δ 2.45 (s, 3H), 3.17–3.26 (m, 4H), 3.90–3.97 (m, 4H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 6.48–6.50 (m, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 6.03 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.40 (m, 1H), 8.07 (s, 2H), 8.20 (d, J = 5.73 Hz, 1H), 9.36 (br s, 2H). LC–MS [M + H]+ = 419.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C20H21N4O2Cl2 = 419.1042, found = 419.1032.

5-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-2,4-dimethylthiazole (57)

Prepared using 42 (200 mg, 0.47 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2,4-dimethyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methanol (82 mg, 0.57 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 57 as an off-white solid (70 mg, 36% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.46 (s, 3H), 2.71 (s, 3H), 3.04–3.07 (m, 4H), 3.61–3.64 (m, 4H), 5.19 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 5.27, 1H), 7.56 (s, 2H), 8.26 (d, J = 5.27 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 449.0913. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C21H23Cl2N4O1S1 = 449.0964, found = 449.0949.

5-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-2,4-dimethyloxazole (58)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2,4-dimethyloxazol-5-yl)methanol (51) (see Supporting Information for synthesis) (53 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 58 as an off-white solid (20 mg, 17% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.47 (s, 3H), 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.10 (s, 2H), 6.72 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 1.28, 5.11 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (s, 2H), 8.26 (d, J = 5.18 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 433.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C21H23Cl2N4O2 = 433.1193, found = 433.1200.

4-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-2,5-dimethyloxazole (59)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2,5-dimethyl-1,3-oxazol-4-yl)methanol (53 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined in the synthesis of 51, to give 59 as an off-white solid (27 mg, 22% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.62 (m, 4H), 4.97 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 1.53, 5.21 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (s, 2H), 8.26 (dd, J = 0.61, 5.21 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 433.1.

4-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-2-methylthiazole (60)

Prepared using 42 (150 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1 equiv) and 2-(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)methanol (54 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 60 as an off-white solid (15 mg, 10% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.77 (s, 3H), 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.62 (m, 4H), 5.22 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 1.45, 5.10 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.56 (s, 2H), 8.26 (d, J = 5.22 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 435.1.

2-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)thiazole (61)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and 2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-thiazole (48 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined in the synthesis of 51, to give 61 as an off-white solid (24 mg, 20% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.62 (m, 4H), 5.44 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 1.41, 5.14 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 3.30 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 2H), 7.86 (d, J = 3.30 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 3.30 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 423.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C19H19Cl2N4O1S1 = 421.0651, found = 421.0641.

4-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)thiazole (62)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and 4-(hydroxymethyl)1,3-thiazole (48 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 62 as an off-white solid (5 mg, 4% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.62 (m, 4H), 5.34 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 1.47, 5.23 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 2H), 7.62–7.63 (m, 1H), 8.27 (dd, J = 0.68, 5.13 Hz, 1H), 8.87 (d, J = 2.09 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 423.1.

5-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-4-methylthiazole (63)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and (4-methylthiazol-5-yl)methanol (52) (for synthesis, see Supporting Information) (54 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 63 as an off-white solid (9 mg, 7% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 2.56 (s, 3H), 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.28 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 1.46, 5.19 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 2H), 8.27 (dd, J = 0.6, 5.19 Hz, 1H), 8.79 (s, 1H). [M + H]+ = 435.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C20H21Cl2N4O1S1 = 435.0808, found = 435.0809.

5-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-2-ethyl-4-methylthiazole (64)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-ethyl-4-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methanol (66 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 64 as an off-white solid (26 mg, 20% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.41 (t, J = 7.81, 3H), 2.47 (s, 3H), 3.00–3.06 (m, 6H), 3.60–3.62 (m, 4H), 5.19 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 1.42, 5.20 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (s, 2H), 8.26 (d, J = 5.13 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 463.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H25Cl2N4O1S1 = 463.1121, found = 463.1124.

5-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)thiazole (65)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and 5-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-thiazole (48 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 65 as an off-white solid (23 mg, 20% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.06–3.08 (m, 4H), 3.64–3.66 (m, 4H), 5.33 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 1.45, 5.20 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (s, 2H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 5.37 Hz, 1H), 8.90 (s, 1H). [M + H]+ = 421.1, 423.1. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C19H19Cl2N4O1S1 = 421.0651, found = 421.064.

5-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-2-isopropyl-4-methylthiazole (66)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-isopropyl-4-methylthiazol-5-yl)methanol (53) (for synthesis, see Supporting Information) (73 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 66 as an off-white solid (37 mg, 28% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.42 (d, J = 7.12 Hz, 6H), 2.48 (s, 2H), 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.31 (sept, J = 6.97 Hz, 1H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.19 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 1.36, 5.23 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 2H), 8.27 (dd, J = 0.68, 5.23 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 477.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C23H27Cl2N4O1S1 = 477.1277, found = 477.1273.

4-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)-2-isopropylthiazole (67)

Prepared using 42 (120 mg, 0.28 mmol, 1 equiv) and 4-(hydroxymethyl)-2-isopropylthiazole (66 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.5 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 67 as an off-white solid (1 mg, 1% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.43 (d, J = 6.85 Hz, 6H), 3.03–3.05 (m, 4H), 3.36 (sept, J = 6.95 Hz, 1H), 3.60–3.62 (m, 4H), 5.26 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 1.47, 5.18 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (s, 2H), 8.26 (d, J = 5.12 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 463.1.

3-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(3-(piperidin-4-yl)propyl)phenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (70)

To a solution of tert-butyl 4-(but-3-en-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (0.58 g, 2.4 mmol, 2 equiv) under argon in anhydrous THF (1 mL) was added 9-BBN (5.1 mL (0.5 M in THF), 2.55 mmol, 2.1 equiv), and the reaction was heated to 90 °C for 1 h in a microwave. To this crude reaction, 3-((4-bromo-2,6-dichlorophenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (0.42 g, 1.2 mmol, 1 equiv) and K3PO4 (1 M in H2O, 2.4 mmol, 2.4 mL, 2 equiv) in anhydrous DMF (2.5 mL) was added and then degassed with argon. (Pd(PPh3)4 (0.024 mmol, 28 mg, 2%) was then added, and the solution was microwaved at 110 °C for 1 h. The reaction was extracted into dichloromethane, washed with water, and dried over MgSO4. The crude material was purified by flash column chromatography, running a gradient from 0% ethyl acetate in hexane to 50% ethyl acetate in hexane. The Boc protected 70 was taken up in dichloromethane (12 mL), trifluoroacetic acid added (6 mL), and the reaction stirred for 2 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo to give a crude residue, which was purified by SCX-2, eluting with methanol to 2 M methanolic ammonia, followed by column chromatography, eluting with dichloromethane to dichloromethane–methanol (80:20) with 1% NH3, to give 70 (0.105g, 10%) as an oil. 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.05–1.13 (m, 2H), 1.23–1.40 (m, 5H), 1.58–1.62 (m, 7H), 2.57 (dd, J = 7.7, 7.7 Hz, 2H), 2.70 (s, 3H), 4.07–4.10 (m, 2H), 5.05 (s, 2H), 7.16 (s, 2H), 7.21 (dd, J = 4.9, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (dd, J = 1.5, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (dd, J = 1.7, 4.9 Hz, 1H). HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C22H23Cl2N4O = 429.124343, found = 429.124407.

3-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(3-(1-methylpiperidin-4-yl)propyl)phenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (71)

3-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(3-(piperidin-4-yl)propyl)phenoxy)methyl)-2-methylpyridine (70) (0.07 g, 0.17 mmol, 1 equiv) was taken up in chloroform (10 mL), treated with paraformaldehyde (0.052 g, 10 equiv), and heated at 55 °C for 1 h. The reaction mixture was then treated with sodium triacetoxyborohydride (0.183 g, 0.86 mmol, 5 equiv), and heating continued for 16 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and then partitioned between dichloromethane and sodium bicarbonate solution. The dichloromethane layer was separated and dried over MgSO4 and solvent removed. The crude material was purified by column chromatography, eluting with dichloromethane to dichloromethane–methanol (95:5) with 1% NH3 to give (71) as a white solid (58 mg, 76% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.23–1.30 (m, 5H), 1.34–1.39 (m, 2H), 1.87–1.92 (m, 2H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 2.56 (dd, J = 7.8, 7.8 Hz, 2H), 2.70 (s, 4H), 2.85 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 2H), 5.05 (s, 2H), 5.33 (s, 1H), 7.16 (s, 2H), 7.21 (dd, J = 5.1, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (dd, J = 1.6, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (dd, J = 1.7, 4.8 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 421.1889. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C23H31Cl2N2O1 = 421.1808, found = 421.1802.

Ethyl 2-Chloronicotinate (72) and Ethyl 2-Ethoxynicotinate (75)

To a suspension of 2-chloronicotinic acid (4.6 g, 29.2 mmol) in ethanol (50 mL), conc. H2SO4 (2 mL) was added dropwise, and the suspension was heated to reflux for 3 h to form a solution. The reaction was then cooled and evaporated in vacuo, then carefully neutralized with sat. aq NaHCO3 and extracted into ethyl acetate. The organic layer was washed with water and then dried over MgSO4, filtered, absorbed onto silica, and purified using flash column chromatography running a gradient from 0% ethyl acetate/hexane to 50% ethyl acetate/hexane, to give the title compounds (ethyl 2-chloronicotinate 72, bottom spot, 2.33 g, 43% yield; ethyl 2-ethoxynicotinate 75, top spot, 923 mg, 16% yield). Ethyl 2-chloronicotinate (72) 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.45 (t, J = 7.61 Hz, 3H), 4.45 (q, J = 7.07 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (dd, J = 4.76, 7.71 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (dd, J = 2.09, 7.87 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (dd, J = 2.09, 4.77 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 186.1. Ethyl 2-ethoxynicotinate (75) 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.14 (t, J = 7.06 Hz, 3H), 1.47 (t, J = 6.92 Hz, 3H), 4.39 (q, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.06 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (dd, J = 4.98, 7.48 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (dd, J = 2.01, 7.48 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (dd, J = 2.01, 4.88 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 196.1.

Prototypical Negishi Reaction between a Chloropyridine and Alkylzinc Bromide

Ethyl 2-Isobutylnicotinate (74a)

Anhydrous THF (9 mL) was added to a flame-dried argon purged flask containing ethyl 2-chloronicotinate (72) (227 mg, 1.2 mmol, 1 equiv) and Pd(tBuP)2 (31 mg, 0.06 mmol, 5%), and the mixture was stirred until clear. To this, isobutylzinc bromide (0.5 M in THF, 2.6 mL, 1.3 mmol, 1.1 equiv) was added dropwise, and the resulting solution was heated at 60 °C overnight. The reaction was absorbed onto silica and eluted to remove baseline material before purifying again by flash column chromatography using 25% ethyl acetate/hexane as the eluent, to give 74a as a yellow oil (164 mg, 66% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 0.95 (d, J = 6.75 Hz, 6H), 1.43 (t, J = 7.25 Hz, 3H), 2.13 (sept, J = 6.75 Hz, 1H), 3.11 (d, J = 7.25 Hz, 2H), 4.41 (q, J = 7.13 Hz, 2H), 8.16 (dd, J = 1.88, 7.75 Hz, 1H), 8.67 (dd, J = 1.88, 4.75 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 208.

Prototypical Suzuki Reaction of a Chloropyridine and Boronic Acid

Ethyl 2-Phenylnicotinate (73)

A solution of ethyl 2-chloronicotinate (72) (793 mg, 4.3 mmol, 1 equiv) and phenylboronic acid (773 mg, 6.4 mmol, 1.5 equiv) in 1 M aq K3PO4 (4 mL) and dioxane (6 mL) in a microwave vessel was degassed with argon for 5 min before addition of Pd(PPh3)4 (64 mg, 0.055 mmol, 5%) and degassing again for a further 5 min before microwaving at 140 °C for 15 min. The reaction mixture was partitioned between dichloromethane and sat. aq NaHCO3, and the organic layer was absorbed onto silica and purified by flash column chromatography running a gradient from 0% ethyl acetate/hexane to 25% ethyl acetate/hexane, affording 73 as an oil (927 mg, 95% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.07 (t, J = 7.19 Hz, 3H), 4.18 (q, J = 7.19 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (dd, J = 4.91, 7.87 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.48 (m, 3H), 7.55–7.57 (m, 2H), 8.14 (dd, J = 1.71, 7.76 Hz, 1H), 8.79 (dd, J = 1.83, 4.78 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 228.2.

Prototypical Pyridyl Ester Reduction to an Alcohol

(2-iso-Butylpyridin-3-yl)methanol (77a)

To a solution of ethyl 2-iso-butylnicotinate 74a (774 mg, 3.7 mmol, 1 equiv) in anhydrous THF (5 mL) at 0 °C, 0.5 M LiAlH4 in THF (5.6 mL, 11.2 mmol, 3 equiv) was added dropwise, and the solution was allowed to warm to room temperature before being stirred at rt for 16 h. Sodium sulfite decahydrate was added to the solution, and the reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and allowed to stir for 30 min. The reaction was filtered, the filtrate layers separated, and the organic layer dried over MgSO4 and evaporated in vacuo to give 77a as a yellow oil (452 mg, 74% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 0.97 (d, J = 6.67, 6H), 2.19 (sept, J = 6.82 Hz, 1H), 2.71 (d, J = 7.42 Hz, 2H), 4.79 (d, J = 5.51 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (dd, J = 4.78, 7.82 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.68 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (dd, J = 1.74, 4.78 Hz, 1H). [M + H] = 166.2.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2-ethoxypyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (79)

Prepared using 42 (200 mg, 0.47 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-ethoxypyridin-3-yl)methanol (78) (87 mg, 0.57 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 79 as an off-white solid (30 mg, 33% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.42 (t, J = 7.21 Hz, 3H), 2.66–2.69 (m, 4H), 3.65–3.68 (m, 4H), 4.41 (q, J = 7.07 Hz, 2H), 6.72 (dd, J = 1.42, 5.21 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 5.04, 7.20 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.72 (dd, J = 1.61, 7.50 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (dd, J = 1.96, 5.04 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 5.24 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 459.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C23H25Cl2N4O2 = 459.1349, found = 459.1339.

4-(3-((2,6-Dichloro-4-(2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridin-4-yl)phenoxy)methyl)pyridin-2-yl)morpholine (80)

Prepared using 42 (200 mg, 0.47 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-morpholinopyridin-3-yl)methanol (110 mg, 0.57 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 80 as an off-white solid (58 mg, 28% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.04–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.28–3.31 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 3.88–3.90 (m, 4H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.79 (dd, J = 1.48, 5.29 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (s, 2H), 8.07 (dd, J = 1.93, 7.51 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 5.23 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (dd, J = 1.93, 4.89 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 500.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C25H28Cl2N5O2 = 500.161457, found = 500.160771.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2-isobutylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (81)

Prepared using 42 (200 mg, 0.47 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-isobutylpyridin-3-yl)methanol (77a) (94 mg, 0.57 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis 51, to give 81 as an off-white solid (86 mg, 40% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.00 (d, J = 6.69 Hz, 6H), 2.23 (sept, J = 6.91 Hz, 1H), 3.04–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 1.44, 5.11 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (dd, J = 4.75, 7.63 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 2H), 7.98 (dd, J = 1.73, 7.77 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (dd, J = 0.65, 5.18 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (dd, J = 1.82, 4.86 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 471.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C25H29Cl2N4O1 = 471.1713, found = 471.1718.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2-phenylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (82)

Prepared using 42 (200 mg, 0.47 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-phenylpyridin-3-yl)methanol 76 (for synthesis, see Supporting Information) (105 mg, 0.57 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined in the synthesis of 51, to give 82 as an off-white solid (122 mg, 53% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 3.03–3.05 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.62 (m, 4H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.76 (dd, J = 1.44, 5.24 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (dd, J = 4.76, 7.68 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.51 (m, 3H), 7.53 (s, 2H), 7.65–7.67 (m, 2H), 8.22 (dd, J = 1.65, 7.82 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 5.21 Hz, 1H), 8.74 (dd, J = 1.71, 4.78 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 491.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C27H25Cl2N4O1 = 491.14, found = 491.1405.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2-propylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (83)

Prepared using 42 (150 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-propylpyridin-3-yl)methanol (77b) (for synthesis, see Supporting Information) (63 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 83 as an off-white solid (33 mg, 21% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.06 (t, J = 7.53 Hz, 3H), 1.79–1.87 (m, 2H), 2.96–2.99 (m, 2H), 3.04–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 1.40, 5.20 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (dd, J = 4.86, 7.55 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 2H), 7.95 (dd, J = 1.73, 7.66 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (dd, J = 0.70, 5.14 Hz, 1H), 8.59 (dd, J = 1.73, 4.87 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 457.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C24H27Cl2N4O1 = 457.1556, found = 457.1552.

1-(4-(3,5-Dichloro-4-((2-isopentylpyridin-3-yl)methoxy)phenyl)pyridin-2-yl)piperazine (84)

Prepared using 42 (150 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1 equiv) and (2-isopentylpyridin-3-yl)methanol (77c) (for synthesis, see Supporting Information) (75 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.2 equiv), according to the Mitsunobu reaction and BOC deprotection procedure outlined for the synthesis of 51, to give 84 as an off-white solid (109 mg, 65% yield). 1H NMR 500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 1.00 (d, J = 6.84 Hz, 6H), 1.65–1.72 (m, 2H), 1.73 (sept, J = 6.87 Hz, 1H), 2.97–3.01 (m, 2H), 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.63 (m, 4H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 1.39, 5.16 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (dd, J = 4.79, 7.74 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (s, 2H), 7.95 (dd, J = 1.80, 7.70 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (dd, J = 0.61, 5.12 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (dd, J = 1.76, 4.92 Hz, 1H). [M + H]+ = 485.2. HRMS [M + H]+ calculated for C26H31Cl2N4O1 = 485.1869, found = 485.1888.

X-ray Crystallography Methods

AfNMT protein–ligand complexes were determined using methods described previously.30 Ternary complexes of AfNMT with myristoyl CoA (MCoA) and ligands of interest were obtained by cocrystallization by incubating protein with 10 mM MCoA plus 10 mM ligand diluted from a 100 mM stock in DMSO prior to crystallization. Diffraction data were measured at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). Data integration and scaling was carried out using XDS36 and AIMLESS37 or the HKL suite.38 Structures were phased by molecular replacement with MOLREP39 from the CCP4 suite40 using the protein coordinates of AfNMT–compound 1 (PDB 4CAX) as a search model. Refinement was carried out using REFMAC5,41 and manual model alteration was carried out using Coot.42 Ligand–coordinate and restraint files were generated using PRODRG,43 and ligands were modeled into unbiased Fobs – Fcalc density maps using Coot.

Coordinates for AfNMT–ligand complexes and associated diffraction data have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession codes 5T5U, 5T6C, 5T6E, and 5T6H for compounds 24, 29, 48, and 49, respectively. Data measurement and refinement statistics are shown in the Supporting Information.

NMT Enzyme Assay

NMT assays44,45 were carried out at room temperature (22–23 °C) in 384-well white optiplates (PerkinElmer). Each assay was performed in a 40 μL reaction volume containing 30 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1.25 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.125 μM [3H]myristoyl-coA (8 Curie (Ci) mmol–1), 0.5 μM biotinylated CAP5.5, 5 nM NMT, and various concentrations of the test compound. The IC50 values for HsNMT1 and HsNMT2 were essentially identical against 80 compounds tested, and for logistical reasons, only HsNMT1 was used in later studies.

Test compound (0.4 μL in DMSO) was transferred to all assay plates using a Cartesian Hummingbird (Genomics Solution) before 20 μL of enzyme was added to assay plates. The reaction was initiated with 20 μL of a substrate mix and stopped after 15 min (HsNMT1 or HsNMT2) or 50 min (TbNMT) with 40 μL of a stop solution containing 0.2 M phosphoric acid, pH 4.0, 1.5 M MgCl2, and 1 mg mL–1 PVT SPA beads (GE Healthcare). All reaction mix additions were carried out using a Thermo Scientific WellMate (Matrix). Plates were sealed and read on a TopCount NXT Microplate Scintillation and Luminescence Counter (PerkinElmer).

ActivityBase from IDBS was used for data processing and analysis. All IC50 curve fitting was undertaken using XLFit version 4.2 from IDBS. A four-parameter logistic dose–response curve was used using XLFit 4.2 Model 205. All test compound curves had floating top and bottom, and prefit was used for all four parameters.

Compound Efficacy and Trypanocidal Activity in Cultured T. brucei Parasites

Bloodstream T. b. brucei s427 was cultured at 37 °C in modified HMI9 medium (56 μM 1-thioglycerol was substituted for 200 μM 2-mercaptoethanol) and quantified using a hemocytometer. For the live/dead assay, cells were analyzed using a two-color cell viability assay (Invitrogen) as described previously.22 Cell culture plates were stamped with 1 μL of an appropriate concentration of test compound in DMSO followed by the addition of 200 μL of trypanosome culture (104 cells mL–1) to each well, except for one column, which received media only. MRC-5 cells were cultured in DMEM, seeded at 2000 cells per well, and allowed to adhere overnight. One microliter of test compound (10 point dilutions from 50 μM to 2 nM) was added to each well at the start of the assay. Culture plates of T. brucei and MRC-5 cells were incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 69 h, before the addition of 20 μL of resazurin (final concentration, 50 μM). After a further 4 h incubation, fluorescence was measured (excitation 528 nm; emission 590 nm) using a BioTek flx800 plate reader.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref. WT077705 and Strategic Award WT083481). We would like to thank Gina McKay for performing HRMS analyses and Daniel James for data management. We thank the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) for synchrotron beamtime and support, and Paul Fyfe for supporting the in-house X-ray facility.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- NMT

N-myristoyltransferase

- T. brucei

Trpanosoma brucei

- T. br. brucei

T. brucei brucei

- HAT

human African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness

- CNS

central nervous system

- TbNMT

T. bruceiN-myristoyltransferase

- HsNMT

human NMT

- LE

ligand efficiency

- PSA

polar surface area

- AfNMT

Aspergillus fumigatus NMT

- HBA

hydrogen bond acceptor

- HBD

hydrogen bond donor

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- MW

molecular weight

- cLogP

calculated LogP

- cLogD

calculated LogD

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- nd

not determined

Supporting Information Available

fThe Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01255.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pink R.; Hudson A.; Mouries M. A.; Bendig M. Opportunities and challenges in antiparasitic drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2005, 4, 727–740. 10.1038/nrd1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Trypanosomiasis, Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs259/en/ (accessed October 15, 2017).

- Brun R.; Balmer O. New developments in human African trypanosomiasis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 19, 415–420. 10.1097/01.qco.0000244045.93016.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P. G. The continuing problem of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Ann. Neurol. 2008, 64, 116–126. 10.1002/ana.21429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wery M. Drug used in the treatment of sleeping sickness (human African trypanosomiasis: HAT). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 1994, 4, 227–238. 10.1016/0924-8579(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R. T.; Nare B.; Phillips M. A. State of the art in African trypanosome drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 1255–1274. 10.2174/156802611795429167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frearson J. A.; Brand S.; McElroy S. P.; Cleghorn L. A.; Smid O.; Stojanovski L.; Price H. P.; Guther M. L.; Torrie L. S.; Robinson D. A.; Hallyburton I.; Mpamhanga C. P.; Brannigan J. A.; Wilkinson A. J.; Hodgkinson M.; Hui R.; Qiu W.; Raimi O. G.; van Aalten D. M.; Brenk R.; Gilbert I. H.; Read K. D.; Fairlamb A. H.; Ferguson M. A.; Smith D. F.; Wyatt P. G. N-myristoyltransferase inhibitors as new leads to treat sleeping sickness. Nature 2010, 464, 728–732. 10.1038/nature08893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Fowler C.; Ersfeld K.; Gull K. CAP5.5, a life-cycle-regulated, cytoskeleton-associated protein is a member of a novel family of calpain-related proteins in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2001, 116, 25–34. 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price H. P.; Panethymitaki C.; Goulding D.; Smith D. F. Functional analysis of TbARL1, an N-myristoylated Golgi protein essential for viability in bloodstream trypanosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 831–841. 10.1242/jcs.01624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price H. P.; Stark M.; Smith D. F. Trypanosoma brucei ARF1 plays a central role in endocytosis and golgi-lysosome trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 864–873. 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price H. P.; Guther M. L.; Ferguson M. A.; Smith D. F. Myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase depletion in trypanosomes causes avirulence and endocytic defects. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2010, 169, 55–58. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price H. P.; Menon M. R.; Panethymitaki C.; Goulding D.; McKean P. G.; Smith D. F. Myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase, an essential enzyme and potential drug target in kinetoplastid parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 7206–7214. 10.1074/jbc.M211391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farazi T. A.; Waksman G.; Gordon J. I. The biology and enzymology of protein N-myristoylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 39501–39504. 10.1074/jbc.R100042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M. H.; Clough B.; Rackham M. D.; Rangachari K.; Brannigan J. A.; Grainger M.; Moss D. K.; Bottrill A. R.; Heal W. P.; Broncel M.; Serwa R. A.; Brady D.; Mann D. J.; Leatherbarrow R. J.; Tewari R.; Wilkinson A. J.; Holder A. A.; Tate E. W. Validation of N-myristoyltransferase as an antimalarial drug target using an integrated chemical biology approach. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 112–121. 10.1038/nchem.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M. H.; Paape D.; Storck E. M.; Serwa R. A.; Smith D. F.; Tate E. W. Global analysis of protein N-myristoylation and exploration of N-myristoyltransferase as a drug target in the neglected human pathogen Leishmania donovani. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22, 342–354. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera L. J.; Brand S.; Santos A.; Nohara L. L.; Harrison J.; Norcross N. R.; Thompson S.; Smith V.; Lema C.; Varela-Ramirez A.; Gilbert I. H.; Almeida I. C.; Maldonado R. A. Validation of N-myristoyltransferase as Potential Chemotherapeutic Target in Mammal-Dwelling Stages of Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004540. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. J.; Fairlamb A. H. The N-myristoylome of Trypanosoma cruzi. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31078. 10.1038/srep31078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzefeld M.; Wright M. H.; Tate E. W. New developments in probing and targeting protein acylation in malaria, leishmaniasis and African sleeping sickness. Parasitology 2017, 1–18. 10.1017/S0031182017000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampoldi F.; Bonrouhi M.; Boehm M. E.; Lehmann W. D.; Popovic Z. V.; Kaden S.; Federico G.; Brunk F.; Grone H. J.; Porubsky S. Immunosuppression and aberrant T cell development in the absence of N-myristoylation. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 4228–4243. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das U.; Kumar S.; Dimmock J. R.; Sharma R. K. Inhibition of protein N-myristoylation: a therapeutic protocol in developing anticancer agents. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2012, 12, 667–692. 10.2174/156800912801784857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinon E.; Morales-Sanfrutos J.; Mann D. J.; Tate E. W. N-Myristoyltransferase Inhibition Induces ER-Stress, Cell Cycle Arrest, and Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 2165–2176. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand S.; Cleghorn L. A.; McElroy S. P.; Robinson D. A.; Smith V. C.; Hallyburton I.; Harrison J. R.; Norcross N. R.; Spinks D.; Bayliss T.; Norval S.; Stojanovski L.; Torrie L. S.; Frearson J. A.; Brenk R.; Fairlamb A. H.; Ferguson M. A.; Read K. D.; Wyatt P. G.; Gilbert I. H. Discovery of a novel class of orally active trypanocidal N-myristoyltransferase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 140–152. 10.1021/jm201091t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand S. W. P.; Thompson S.; Smith V.; Bayliss T.; Harrison J.; Norcross N.; Cleghorn L.; Gilbert I.; Brenk R.. N-Myristoyl transferase inhibitors. Patent WO2010026365, 2010.

- Brand S.; Norcross N. R.; Thompson S.; Harrison J. R.; Smith V. C.; Robinson D. A.; Torrie L. S.; McElroy S. P.; Hallyburton I.; Norval S.; Scullion P.; Stojanovski L.; Simeons F. R. C.; van Aalten D.; Frearson J. A.; Brenk R.; Fairlamb A. H.; Ferguson M. A. J.; Wyatt P. G.; Gilbert I. H.; Read K. D. Lead optimization of a pyrazole sulfonamide series of Trypanosoma brucei N-myristoyltransferase inhibitors: Identification and evaluation of CNS penetrant compounds as potential treatments for stage 2 human african trypanosomiasis. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9855–9869. 10.1021/jm500809c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L.; Groom C. R.; Alex A. Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9, 430–431. 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebiike H.; Masubuchi M.; Liu P.; Kawasaki K.; Morikami K.; Sogabe S.; Hayase M.; Fujii T.; Sakata K.; Shindoh H.; Shiratori Y.; Aoki Y.; Ohtsuka T.; Shimma N. Design and synthesis of novel benzofurans as a new class of antifungal agents targeting fungal N-myristoyltransferase. Part 2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 607–610. 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]