Abstract

Estimating the time after death is an important aspect of the role of a forensic expert. After death, the body undergoes substantial changes in its chemical and physical composition which can prove useful in providing an indication of the post-mortem interval. The most accurate estimate of the time of death is best achieved early in the post-mortem interval before the many environmental variables are able to affect the result. Whilst dependence on macroscopic observations was the foundation of the past practice, the application of histological techniques is proving to be an increasingly valuable tool in forensic research. The present study was conducted to evaluate the histologic post-mortem changes that take place in human gingival tissues and to correlate these changes with the time interval after death. Thirty one samples of post-mortem human gingival tissues were obtained from a pool of decedents at varied post-mortem intervals (0-8hrs, 8-16hrs, 16-24 hrs). Ante-mortem samples of gingival tissues for comparison were obtained from patients undergoing crown lengthening procedure. Histological changes in the epithelium (cytoplasmic and nuclear) and connective tissue were assessed. The initial epithelial changes observed were homogenization and eosinophilia while cytoplasmic vacuolation and other alterations, including shredding of the epithelium, ballooning, loss of nuclei and suprabasilar split were noticed in late post-mortem interval (16-24 hrs). Nuclear changes such as vacuolation, karyorrhexis, pyknosis and karyolysis became increasingly apparent with lengthening post–mortem intervals. Homogenizations of collagen and fibroblast vacuolation were also observed. To conclude; the initiation of decomposition at cellular level appeared within 24 hours of death and other features of decomposition were observed subsequently. Against this background, histological changes in the gingival tissues may be useful in estimating the time of death in the early post-mortem period.

KEYWORDS: Post-mortem Interval, Histologic Changes, Gingiva, Eosinophilia, Homogenization, Vacuolation

Introduction

The period of time before death is known as the ante-mortem period whilst that after death is called the post-mortem period. After death, the body undergoes dramatic changes in its chemical and physical composition, which are termed as post-mortem changes. These changes can provide an indication of the post-mortem interval (PMI). (1) No topic in forensic medicine has been investigated as thoroughly as that of determining the time of death on the basis of post mortem findings. (2) There have been many different methods used at autopsy in an attempt to accurately and systematically determine the post-mortem interval and exact time of death. They include examination of the external physical characteristics of the body (3) such as autolysis, algor mortis, rigor mortis, livor mortis, post-mortem clotting, putrefaction and the appearance of adipocere (4), chemical changes detected in body fluids, analysis of stomach contents, determination of internal temperatures, and scene markers. (3) Some of these methods are relatively accurate under specific and controlled circumstances. However, the unpredictability of various environmental factors has prevented the development of a single reliable predictor. The most accurate estimates of the time of death are best achieved early in the post-mortem period before the many environmental variables can have any significant effect on the result. (5)

Whilst dependence on macroscopic observations together with a sense of ingenuity and “lateral thinking” were the former keystones of past forensic practice the application of both histological and molecular diagnostic techniques is becoming increasingly important as an essential part of the armamentarium of tools used in modern forensic pathology. (6) Using light microscopy cells are recognized as being dead only after they have undergone a sequence of morphological changes. (7) These changes occur as a result of two cellular processes - apoptosis, a programmed, orderly form of cell death, and necrosis, an disorderly and unpredictable form of cell death. (4) The necrotic cells show increased eosinophilia, and may have a more glassy homogenous appearance than normal cells. (7) Nuclear changes may appear in the form of one of three patterns, the basophilia of the chromatin may fade (karyolysis), nuclear shrinkage (pyknosis) may occur or the pyknotic or partially pyknotic nucleus may undergo fragmentation (karyorrhexis). (7) Studies are available relevant to the gross and histologic changes that occur in the skin after death (5), However, there have been no systemic studies published in the English literature that relate to the histological changes that occur in human gingival tissues after death.. The aim of the present study was to evaluate post-mortem epithelial (cytoplasmic & nuclear) and connective tissue degenerative changes observed in the gingival tissues obtained from 31 non-refrigerated bodies (experimental group). It was postulated that there may be a specific pattern of histological changes observed that may prove useful to determine the time interval after death. Standardization was performed using 10 samples of gingival tissues obtained from clinically healthy individuals following crown lengthening procedure (control group).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The investigation was conducted on samples of labial gingival tissues obtained at autopsy by the Department of Forensic Medicine in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was in accordance with the institution (IRB approval #559). General information, including the age, sex, date of death, cause of death, and the time elapsed after death and arrival at the mortuary was determined. The bodies were not subject to refrigeration during this period between death and arrival at the mortuary. On arrival at the mortuary the cadavers were placed in a dry shaded area in temperatures that varied from cool to temperate (380F-770F). Biopsies from the labial gingival tissues were taken for analysis.

The study comprised of 2 groups:

-

Experimental group: this consisted of 31 samples from the labial gingival tissues obtained from un-refrigerated decedents. The group was further subdivided into 3 sub- groups;

Sub- group A: Tissues obtained with <8 hrs of death (n=10),

Sub- group B: Tissues obtained within 8-16 hrs of death (n=10)

Sub- group C: Tissues obtained within 16-24 hrs of death (n=11).

For sampling purposes it was deemed appropriate to divide this experimental group into three sub-divisions based on an eight hour difference. This decision was based on the fact that the process of cellular decomposition commences 10 hours post-mortem and other decomposition changes occur subsequently. (4)

Control group: this consisted of 10 gingival samples from clinically healthy individuals following crown - lengthening procedure. Firmly attached gingival tissue with no loss of clinical attachment and devoid of clinical signs of inflammation were included in the sample.

The specimens were fixed immediately in 10% formalin, processed, sectioned and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. The specimens were examined under a light microscope by 3 independent observers who were unaware of the time of death. The changes in the epithelium (cytoplasmic & nuclear) and connective tissue were assessed. Sequential analysis of the following histological changes of the biopsies of all individuals was carried out.

-

Epithelial changes

Cytoplasmic features: eosinophila, homogenization/ presence of distinct cellular outline and vacuolation.

Nuclear features: presence/absence of distinct nuclear outline, karyolysis, pyknosis, karyorrhexis and vacuolation.

Presence of intercellular bridging/ junctions.

Separation of epithelium and connective tissue

-

Connective tissue changes

distribution of collagen fibres,

fibroblasts vacuolation,

type and distribution of inflammatory component

The degree of histological (epithelial and connective tissue) changes in the post-mortem samples was correlated to the time interval since death. Comparison with ante-mortem samples was undertaken.

RESULTS

Epithelial changes

The initial changes observed in the epithelium of the early post-mortem period (0-8hrs) were homogenization and eosinophilia, predominantly seen in the superficial and spinous epithelial cell layers. This spread progressively to include the entire thickness of the epithelium. The changes became more apparent with increasing length of post-mortem interval (8-16 and 16-24 hrs). Cytoplasmic vacuolation in the superficial and the spinous cell layers of the epithelium was evident after a post-mortem period of 8 hrs and was limited to the spinous layer solely in sub group C. Nuclear changes such as vacuolation, karyorrhexis, pyknosis and karyolysis were present early after death (sub group A) in the superficial layers and were seen extending throughout the epithelium in the late post-mortem intervals (sub group B and C). Other epithelial changes noticed were shredding of epithelium in the superficial layers, ballooning, loss of nuclei and suprabasilar split. All of these changes became progressively more apparent toward the end of the late post-mortem interval (sub group C). An exceptional biphasic pattern of staining was also evident in samples taken from sub group C. None of the features described above were present in the control group (group II). Both the groups including sub groups A, B and C did not demonstrate any split at the junction of epithelium and connective tissue interface (Table 1, Figure 1, 2, 3).

Table 1. - Histologic postmortem changes in the gingival tissue at different PMI.

| Histologic postmortem features | PMI <8 hrs (n=10) | PMI 8-16 hrs (n=10) | PMI 16-24 hrs (n=11) | Control (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogenization | In superficial & spinous layer (10) | Throughout the epithelium (10) | Throughout the epithelium (11) | Absent (10) |

| Eosinophilia | In superficial & spinous layer (10) | Throughout the epithelium (10) | Throughout the epithelium (11) | Absent (10) |

| Cytoplasmic vacuolation | Absent (10) | In superficial & spinous layer (7) | In superficial & spinous layer (9) | Absent (10) |

| Karyolysis | In superficial layer (4) | In superficial & spinous layer (7) | In superficial & spinous layer (9) | Absent (10) |

| Pyknosis | In superficial & spinous layer (9) | Throughout the epithelium (10) | Throughout the epithelium (11) | Absent(10) |

| Karyorrhexis | In superficial layer (9) | In superficial & spinous layer (10) | Throughout the epithelium (11) | Absent (10) |

| Nuclear vacuolation | In superficial & spinous layer (9) | Throughout the epithelium (10) | Throughout the epithelium (11) | Absent (10) |

| Epithelium (shredding) | In few (3) | Present (9) | Present (11) | Absent (10) |

| Epithelium (ballooning) | In one sample (1) | Present (5) | Present (7) | Absent (10) |

| Epithelium (disruption) | Absent (10) | Absent (10) | Present (6) | Absent (10) |

| Suprabasilar sepration | Absent (10) | In few (2) | Present (7) | Absent (10) |

| Sepration b/w Epi & CT | Absent (10) | Absent (10) | Absent (11) | Absent (10) |

| Distribution of collagen | Homogenized (7) | Homogenized (clumps in few) (9) |

Homogenized (clumps in few) (9) | Intact, Parallel arrangement (10) |

| Distribution of inflammation | Diffuse (10) | Focal & diffuse (10) | Focal & diffuse (11) | Absent (10) |

| Type of inflammation | Lymphocytes (10) | Lymphocytes & plasma cells (10) | Lymphocytes & plasma cells (11) | Absent (10) |

| Fibroblasts vacuolation | Present in few (5) | Present (8) | Present in all (11) | Absent (10) |

| Biphasic staining pattern | Absent (10) | Absent (10) | Present (11) | Absent (10) |

PMI: Post-mortem interval

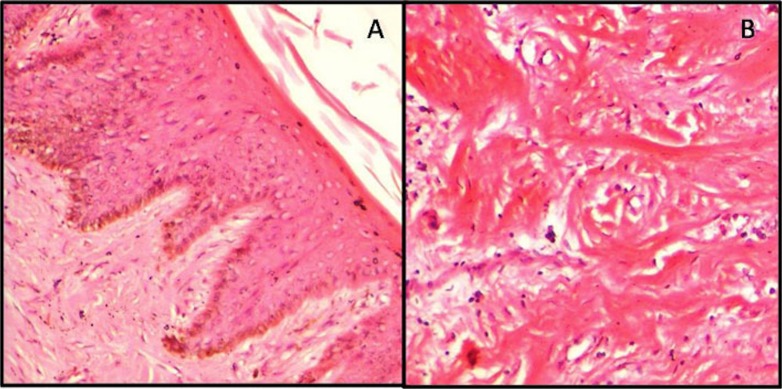

Fig.1.

Early postmortem changes in the gingiva (0-8hrs). (A) Eosinophilia, homogenization and nuclear changes in superficial layers of epithelium (H&E,X100). (B) Homogenization of collagen bundles in the connective tissue stroma.

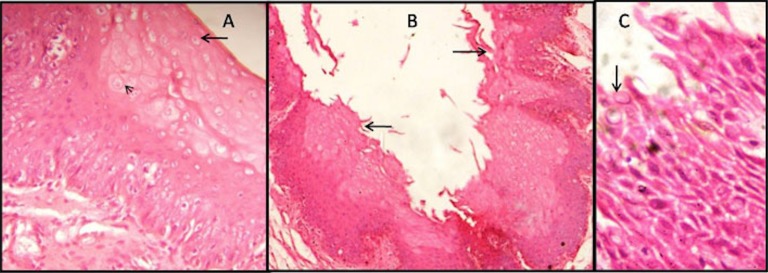

Fig. 2.

Late postmortem changes in the gingiva (8-16hrs, 16-24hrs). (A) Cytoplasimic vacuolation (arrow) and ballooning of cells (arrow head) evident in the superficial and spinous layer of epithelium in 8-16 hrs of PMI (H&E,X400). (B) Shredding (arrow) and other epithelial changes are observed in the whole epithelium in subgroup C (H&E,X100). (C) Disruptive epithelium showing nuclear degenerative changes (arrow) in subgroup C (H&E,X400).

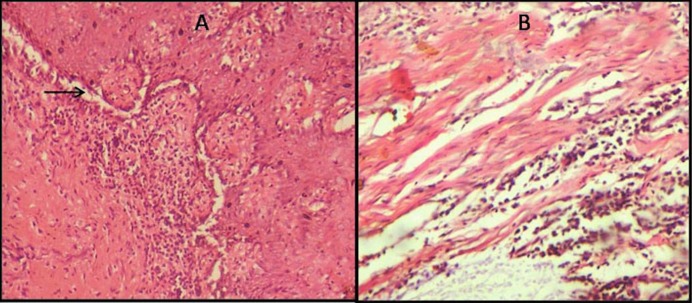

Fig. 3.

(A) Suprabasilar split (arrow) observed in late postmortem period (16-24hrs) (H&E,X100). (B) Connective tissue stroma shows homogenization of collagen bundles with fibroblast vacuolation and moderate inflammatory infiltrate (16-24hrs) (H&E,X100).

Connective tissue changes

An intact parallel arrangement of collagen fibres were seen in the control group while homogenization of collagen bundles was evident in the experimental group with formation of clumps in the later period of PMI (sub group B and C). Fibroblast vacuolation commenced early after death and was most prominent in sub group C.

The inflammatory component was diffusely spread in the early samples taken in the PMI (0-8 hrs). In later samples taken from subgroups B and C (8-16hrs and 16-24hrs) the inflammatory component was focal to diffuse and composed predominantly of lymphocytes. Sub groups B and C also showed evidence of plasma cells (Table 1, Figure 1, 3).

DISCUSSION

Whilst traditionally established techniques are commonly used to estimate the time of death during routine medico legal autopsies there is a trend toward the development and introduction of newer techniques. It is established that the reliance on a single technique can produce erroneous outcomes. (8) Following death many physico-chemical changes begin to take place in the body in an orderly manner and continue until the body eventually decomposes. Similarly, ongoing cellular changes also occur after death that depends on the time interval post-mortem and the circumstances of the death. At cellular level, in the first instance, respiration ceases and glycolysis proceeds. This results in the production of lactic acid and a corresponding decline in the pH of

the cellular contents. Ultimately all activities of cell metabolism terminate and the subsequent predominance of lytic enzymes results in autolysis. Post-mortem changes are associated with tissue degradation and the release of proteolytic lysosomal enzymes from the cells. (9, 10) Like other body tissue cells, oral mucosa loses its normal morphology as a result of post-mortem autolysis and putrefaction. These cellular changes can be a useful criterion and marker for estimating the post-mortem interval. Currently there are no publications in the literature that correlate the degree of histological changes observed in post-mortem human gingival tissues with the time since death. The present study was aimed to assess the early post-mortem changes in the human gingival tissues and emphasizes the need for further research.

The aim of this study was to observe and assess the various sequential changes seen in the microscopic appearance of human gingival tissues (epithelium and connective tissue) at different PMI. The initial changes observed in the early post-mortem period (0-8hrs) in the epithelium included homogenization and eosinphilia predominantly in the superficial and spinous layers. This spread progressively to include the entire thickness of the epithelium. The changes became more apparent with increasing length of post-mortem interval (8-16 and 16-24 hrs).

Homogenization could be attributed to a decline in the level of cellular glycogen content. Eosinophilia could be attributed to both depletion of normal basophilia transmitted by RNA in cytoplasm and also in part due to augmentation of eosin binding to denatured intra-cytoplasmic proteins. Cell death results in a decline of intra-cellular pH which activates the release of DNAase. This, in turn, results in fading of the chromatin (karyolysis) (6, 7). Karolysis was evident in the superficial layers of all of the experimental samples. Pyknosis (result of nuclear shrinkage) and karyorrhexis (fragmentation of the nucleus) (7, 11) was predominantly evident in the superficial layers in the early post-mortem interval samples. In the other later post-mortem samples all of these changes were apparent throughout the entire thickness of the epithelium.

With increasing post-mortem intervals nuclei may undergo complete dissolution. This phenomenon was observed in later post-mortem samples from sub-groups B and C (16-24 hrs). Furthermore, vacoluation of the cells due to digestion of the organelles has also been reported after death. (7, 10-12). In the present study, the nuclear vacoulation was observed as early as 0-8 hrs after death and at this post-mortem interval vacuolation was limited to the superficial layers of epithelium. With increasing post-mortem intervals (8-16, 16-24hrs) vacuolation progressively increased to include the entire thickness of the epithelium.

Paradoxically, cytoplasmic vacoulation was observed only in the late post-mortem samples (8-16, 16-24 hrs) and was utterly absent in earlier samples (0-8 hrs). This observation could suggest that nuclear degenerative changes usually precede cytoplasmic degenerative changes after death. Ballooning of the cells that becomes apparent just after death was also seen in the later post-mortem intervals (8-16,16-24 hrs). This may represent a loss of potential of the cell to actively remove the influx of ions from the plasma membrame. (7) Additionally, loss of architecture of the epithelium in the late post-mortem interval as a result of shredding of the superficial layers and disruption may be caused by severance of the cells and denaturation of the proteins due to the lytic activity. (4)

All of the gingival samples exhibited an intact epithelial - connective tissue junction without any severance/ breach. This could signify that the separation of the epithelium and the lamina propria could be a change that could occur in later post-mortem intervals i.e. after 24 hrs. It is significant that Kovarik et al observed that the initial cleavage in the dermo- epidermal junction of skin occurred after 24 hrs post-mortem. (5)

In relation to the connective tissue component of the control group a parallel arrangement of collagen fibres was recognised as normal. However clumping of collagen fibres was observed within a few samples of sub-group B and within almost all of the samples within sub-group C.

As a degenerative change, fibroblasts revealed nuclear vacoulation. This nuclear vacuolation increased proportionately with the passage of time post-mortem. It was more pronounced in samples taken 16–24after death than in the samples obtained less than 8hrs after death.

These changes could be due to hypoxia resulting from the severance from the vascular network and the start of inflammation. (10-12). Inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes and plasma cells, (in subgroup B and C) were seen distributed focally and in diffuse patterns prominently in the sub-epithelial connective tissue.

In comparing the histological findings of the experimental and control groups none of the changes seen in gingival tissues of the samples obtained post-mortem were observed in the ante-mortem samples.

CONCLUSION

There is a paucity of information in the literature in relation to the decomposition of oral tissues. As a consequence this can place restraints on the role of forensic pathologists to estimate the time of death. Although there are many methods available to estimate the time of death, none is reliable enough by itself as a “stand alone” method because of the inevitable influence of unpredictable external factors. In this context the histological changes that occur post-mortem in human gingival tissues would appear to be useful method to estimate the time of death in the early PMI (0-24 hrs). However, more research is needed to verify, refine and expand these initial results. Despite some constraints, such as the limited number of subjects and the relatively short time span of the post-mortem period, the present study demonstrated the potential of this method as a tool for use in forensic practice. Further research using larger sample sizes and an extended time range could assist forensic practitioners in estimating a precise time of death.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gunn A. The decay, discovery and recovery of human bodies. In: Essential forensic biology, 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: Willey, 2009, p 11-13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker RF. Becker, Aric W. Dutelle. Time of death determination. In: Criminal investigation, 4th ed. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2013, p 239. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Maio VJ, Di Maio D. Time of death. In: Forensic Pathology, 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2001, p 21– 41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pradeep GL, Uma K, Sharada P, Prakash N. Histological assessment of cellular changes in gingival epithelium in ante-mortem and post-mortem specimens. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2009;1(2):61–5. 10.4103/0974-2948.60375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovarik C, Stewart D, Cockerell C. Gross and histologic postmortem changes of the skin. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2005;26(4):305–8. 10.1097/01.paf.0000188087.18273.d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert L, Siang LH. Forensic histopathology. In: Tsokos M, Forensic Pathology Reviews, 5th ed. New Jersey: Springer, 2008, p 239-65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar V, Cotran RS, Robbins SL. Textbook of basic pathology, 5th ed. Elsevier, India, 1992, p 22-5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheikh NA. Estimation of postmortem interval according to time course of potassium ion activity in cadaveric synovial fluid. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2007;1. Accessed 1 January 2015. Available at http://www.indmedica.com

- 9.Parikh CK. Textbook of medical jurisprudence, forensic medicine and toxicology. 6th ed, New Delhi: CBS publishers and distributors, 2004. p. 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henssge C, Madea B. Estimation of time since death. Forensic Sci Int. 2007;165(2–3):182–4. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobb JP, Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE, Buchman TG. Mechanism of cell injury and death. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:3–10. 10.1093/bja/77.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babapulle CJ, Jayasundera NP. Cellular changes and time since death. Med Sci Law. 1993;33(3):213–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]