Abstract

Study Objectives:

Sleep disorders are frequent in stroke patients. The prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), and restless legs syndrome (RLS) among stroke survivors is up to 91%, 72%, and 15%, respectively. Although the relationship between EDS and SDB is well described, there are insufficient data regarding the association of EDS with RLS. The aim of this study was to explore the association between EDS, SDB, and RLS in acute ischemic stroke.

Methods:

We enrolled 152 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was used to assess EDS. SDB was assessed using standard overnight polysomnography. All patients filled in a questionnaire focused on RLS. Clinical characteristics and medication were recorded on admission.

Results:

EDS was present in 16 (10.5%), SDB in 90 (59.2%) and RLS in 23 patients (15.1%). EDS was significantly more frequent in patients with RLS in comparison with the patients without RLS (26.1% versus 7.8%, P = .008). ESS was significantly higher in the population with RLS compared to the population without RLS (7 [0–14] versus 3 [0–12], P = .032). We failed to find any significant difference in the frequency of EDS and values of ESS in the population with SDB compared to the population without SDB. Presence of RLS (beta = 0.209; P = .009), diabetes mellitus (beta = 0.193; P = .023), and body mass index (beta = 0.171; P = .042) were the only independent variables significantly associated with ESS in multiple linear regression analysis.

Conclusions:

Our results suggest a significant association of ESS with RLS, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Citation:

Šiarnik P, Klobučníková K, Šurda P, Putala M, Šutovský S, Kollár B, Turčáni P. Excessive daytime sleepiness in acute ischemic stroke: association with restless legs syndrome, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and sleep-disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(1):95–100.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, diabetes mellitus, excessive daytime sleepiness, obesity, polysomnography, restless legs syndrome, sleep-disordered breathing

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Sleep disorders are frequent in stroke patients. There are conflicting data regarding the association between excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep-disordered breathing, and restless legs syndrome. The aim of this study was to explore the association of excessive daytime sleepiness with sleep-disordered breathing, restless legs syndrome, and other clinical characteristics in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Study Impact: Our study confirmed high prevalence of sleep disorders in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Presence of restless legs syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and body mass index were the only independent variables significantly associated with the measures of daytime sleepiness (the Epworth Sleepiness Scale). In acute ischemic stroke, restless legs syndrome, obesity, and metabolic factors seem to be the most important variables associated with the measures of daytime sleepiness, whereas the role of sleep-disordered breathing seems to be minor.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep disorders are frequent in stroke patients. The prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), and restless legs syndrome (RLS) among stroke survivors is up to 91%, 72%, and 15%, respectively.1–4

Numerous medical conditions are associated with EDS in stroke patients, including cardiovascular morbidity.5,6 EDS is assumed to be the most commonly caused by sleep deprivation, SDB, medication, or other medical and psychiatric conditions. Primary hypersomnia is less common.7,8 Although the relationship between EDS and SDB in the general population is well described, the data in stroke patients are rather inconsistent.9–11 There are also conflicting data regarding the association between EDS and RLS. Some of the studies found higher Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores in subjects with RLS, whereas other failed to identify such findings.12–18 The aim of this study was to explore the association of EDS with SDB and RLS in acute ischemic stroke. An extensive literature search did not reveal any study on this topic.

METHODS

We prospectively enrolled 152 consecutive patients hospitalized in the stroke unit of the 1st Department of Neurology, Comenius University Bratislava with the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke from January 2011 to June 2016. The diagnosis was confirmed clinically and neuroimaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) was used to localize the site of the ischemic lesion. To assess baseline stroke severity, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and modified Rankin Scale were used.19,20 Patients with severe stroke (NIHSS ≥ 15) were excluded. Moreover, subjects with impaired consciousness, agitated confusion, acute chest infection, or those who refused to participate were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and all patients provided informed consent.

The baseline evaluation of all patients included assessment of clinical and demographic characteristics including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and current smoking habit. Medical history and current medication on admission were recorded in all patients. Medical records of all patients were reviewed to search for medical conditions (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, renal insufficiency, cancer, hepatopathy, hypothyroidism, parkinsonism, epilepsy, gastrointestinal disorders [peptic ulcer disease and gastro-oesophageal reflux]) and medication (alpha-adrenergic blocking agents, beta-adrenergic blocking agents, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antihistamines, antiparkinsonian agents, anxiolytics, genitourinary smooth muscle relaxants, opiate agonists) that could contribute to EDS.8,21,22

The sleep study was performed 4.3 ± 2.8 days after the stroke onset. ESS was used to assess EDS, and ESS score of 10 or more indicated EDS.23 The minimum criteria defined by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group were used to establish the diagnosis of RLS.24 To avoid false-positive diagnosis, the questionnaires were distributed during an interview with a patient. The sleep workup included full standard overnight polysomnography using Alice 5 device (Philips Respironics, Netherlands). Standardized criteria were used for scoring of sleep parameters and respiratory events. Apnea was defined as the cessation or the reduction of airflow ≥ 90% for more than 10 seconds, hypopnea as a reduction in airflow ≥ 50% for more than 10 seconds with oxygen desaturation > 3%.25 Apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 5 was considered as a presence of SDB. Periodic limb movements of sleep (PLMS) index (number of PLMS per hour of sleep) was assessed. Scores were blinded to the baseline characteristics of the study population.

SPSS version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States) was used for the statistical analyses. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (%), continuous variables as means (± standard deviation) or median (interquartile range [IQR], minimal-maximal values).

The chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Student t test were used for group comparison of particular variables. To determine relationships between ESS and characteristics of the population, Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients were used. Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify factors that contributed to the ESS. All tests were 2-sided and values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

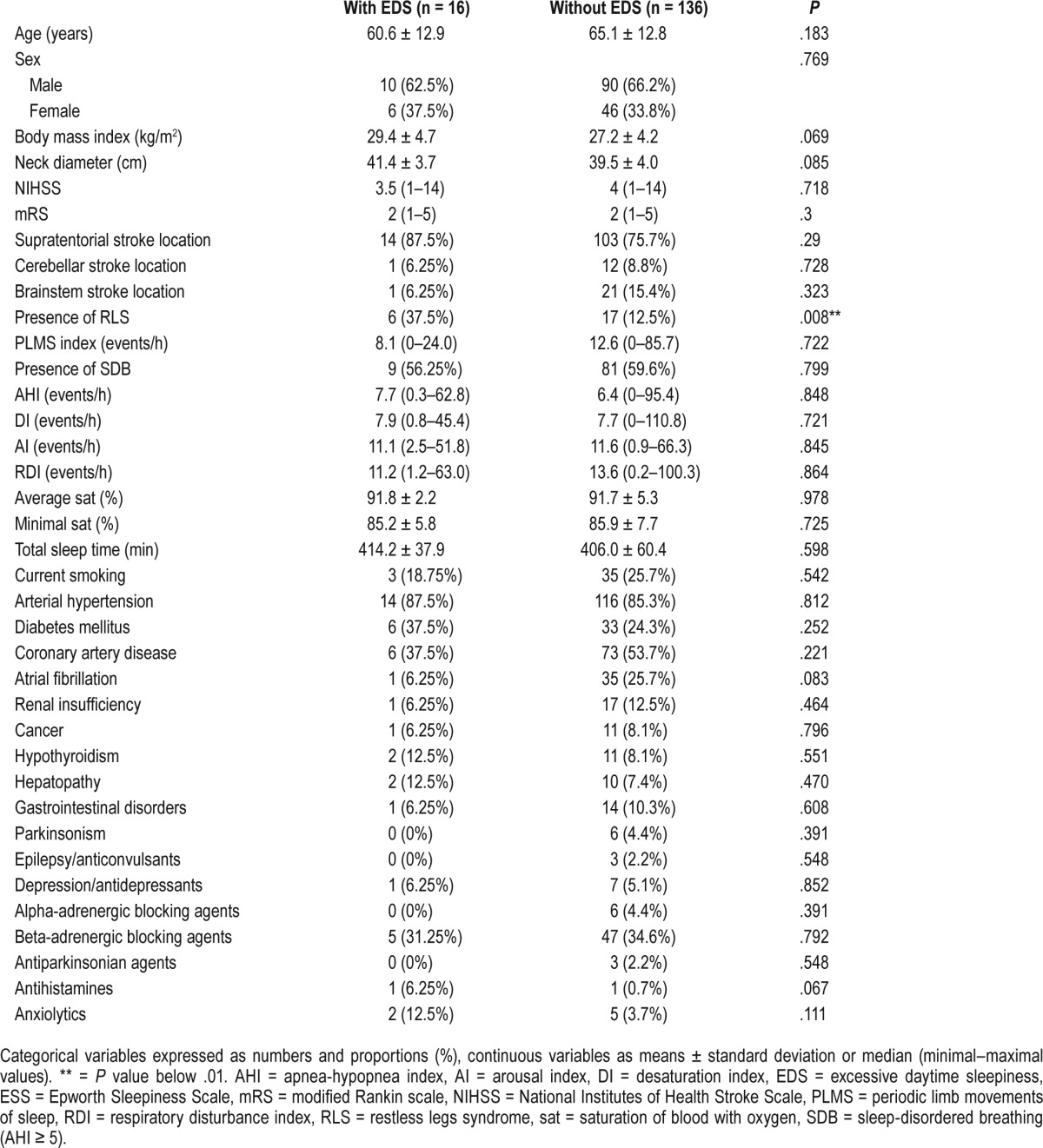

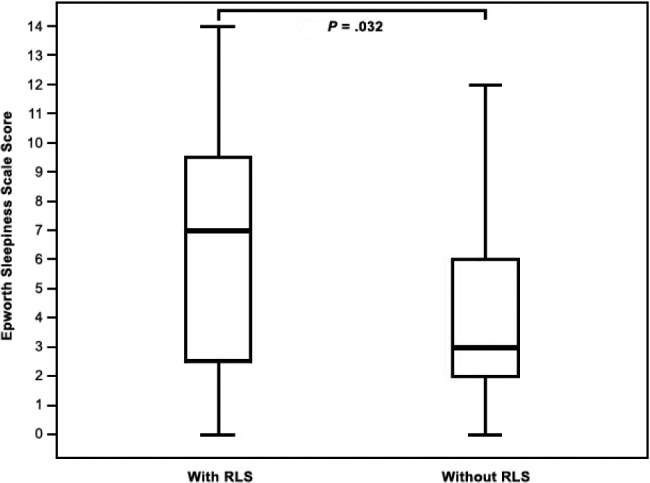

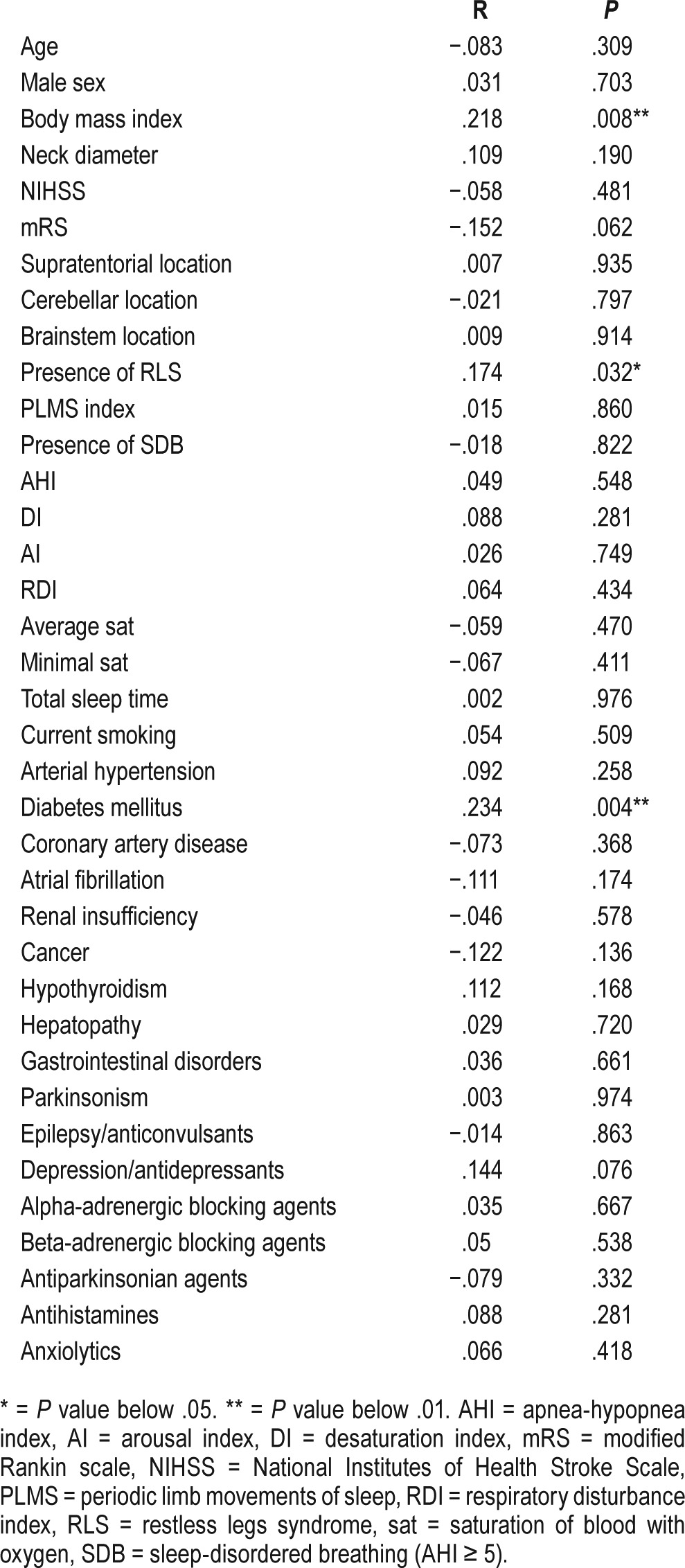

EDS was present in 16 patients (10.5%), SDB in 90 patients (59.2%), and RLS in 23 patients (15.1%). Baseline characteristics of the study population with EDS and without EDS are included in Table 1. RLS was significantly more frequent in patients with EDS when compared with the rest of the study population (37.5% versus 12.5%, P = .008). EDS was significantly more frequent in patients with RLS when compared with the rest of the study population (26.1% versus 7.8%, P = .008). ESS was found to be significantly higher in the population with RLS than without (7 [0–14, IQR: 8] versus 3 [0–12, IQR: 4], P = .032), see Figure 1. We failed to find any significant difference in frequency of EDS in populations with presence or absence of SDB (10.0% versus 11.3%, P = .799). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the values of ESS in the population with SDB compared with the rest of the population (4 [0–13; IQR: 5] versus 4 [0–14; IQR: 5.25], P = .821). Statistically significant correlation was found between the values of ESS and the presence of RLS, diabetes mellitus, and the values of BMI. There was a statistically nonsignificant trend toward higher values of ESS in patients with depression/use of antidepressants (Table 2). The presence of RLS (beta = 0.209; P = .009), diabetes mellitus (beta = 0.193; P = .023), and BMI (beta = 0.171; P = .042) were the only independent variables significantly associated with the values of ESS in multiple linear regression analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in the population with and without EDS.

Figure 1. Epworth Sleepiness Scale in those with and without RLS.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale in subpopulations with and without RLS (7 [0–14, IQR: 8] versus 3 [0–12, IQR: 4], P = .032). IQR = interquartile range, RLS = restless legs syndrome.

Table 2.

Correlation between Epworth Sleepiness Scale and baseline characteristics of the study population.

DISCUSSION

In concordance with previous studies, our study confirmed high prevalence of sleep disorders in stroke patients.1–4 EDS was present in 10.5%, SDB in 59.2%, and RLS in 15.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first one to search for the simultaneous association of EDS with SDB and RLS in acute ischemic stroke. Our results showed significant association between EDS and RLS, but we failed to find a link between EDS and SDB in patients with acute ischemic stroke. In our population, presence of RLS, diabetes mellitus, and BMI were the only independent variables significantly associated with ESS in multiple linear regression analysis. The lack of association between ESS and SDB measures suggest that ESS is not a useful screening tool for SDB in patients with acute ischemic stroke. However, we suppose that stroke patients with EDS according to the ESS should undergo screening for other sleep disorders, including RLS.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies. Bixler et al. in a cross-sectional study of the general population found that the occurrence of depression was the most significant risk factor for the complaint of EDS, followed by BMI, age, subjective estimate of sleep duration, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and sleep apnea. In contrast with other variables, sleep apnea did not make a significant contribution to this logistic regression model. These authors supposed that the presence of EDS is more strongly associated with depression and metabolic factors than with SDB.26 In our study, the presence of diabetes mellitus and BMI belonged to the independent variables significantly associated with the values of ESS in multiple linear regression analysis. EDS has been shown to be associated with metabolic syndrome and obesity also by other authors.27,28 A variety of medical conditions and mental health disorders may be associated with poor sleep and EDS.3,29,30 Drug-induced sleepiness is also one of the most common side effects of central nervous system active drugs, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihypertensives, antiepileptic agents, and other central nervous system active agents.8 In our cohort, we observed a statistically nonsignificant trend toward higher values of ESS in patients with current use of antidepressants. Similar to findings in a previously mentioned study, we failed to find any signifi-cant association between ESS and other medical conditions, medications, or polysomnographic parameters.26 Even though EDS is one of the most common symptom of SDB, the association between EDS and the severity of SDB has been shown to be weak.31,32 In addition, there was no significant difference in the values of ESS in the population with SDB in comparison with the rest of our study cohort. Although some of the studies discovered the association of EDS with subcortical, thalamic, diencephalic, and pontine stroke, in our study there was no association between the values of ESS and location of ischemic lesion.33–37 Our results showed no statistically significant relationship between ESS and the severity of stroke assessed by NIHSS, but there was a trend toward lower values of ESS in patients with more severe baseline degree of disability or dependence in the daily activities according to modified Rankin Scale. Decreased sleepiness in such patients could be explained by the fact that physical needs of dependent patients are usually met by caregivers and low-level physical activity does not exhaust them so much.10 We have to admit that ESS was assessed soon after the stroke onset, so the ESS could reflect prestroke sleepiness more than the poststroke sleepiness. Especially the association with poststroke disability and SDB (due to frequent poststroke new-onset SDB) is disputable for this reason.

There are increasing data regarding daytime sleepiness in patients with the presence of RLS.38–41 There are several potential mechanisms linking RLS with EDS, including difficulties initiating sleep or maintaining sleep, and sleep fragmentation due to PLMS. In our study, we failed to find any significant difference in PLMS index in population with EDS in comparison with the population without EDS. Similarly, there was no significant correlation between PLMS index and ESS. Nevertheless, very little is still known about increased daytime sleepiness in patients with RLS, and the presence of other underlying mechanisms is possible. We are not aware of any previous studies that assessed the presence of RLS to be the independent variable significantly associated with the measure of EDS.

We must admit several limitations of our study. Although the ESS is a reliable self-administered questionnaire, we suppose that our findings should be verified using the Multiple Sleep Latency Test, the gold standard for measuring EDS, in future prospective studies.1,42 Future studies should also assess the effect of duration of particular sleep stages as well as daytime physical activity on EDS.43 These variables were not included in our analysis. Absence of the most severe stroke patients is another limitation of our study. We suppose that the presence of such patients could help to determine the causes of EDS in real-life stroke patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study confirmed a high prevalence of sleep disorders in patients with acute ischemic stroke. In our population, RLS, diabetes mellitus, and BMI were the only independent variables significantly associated with ESS in multiple linear regression analysis. RLS, obesity, and metabolic factors seem to be the most important variables associated with the measure of EDS, whereas the role of SDB seems to be minor. Future studies should focus on mechanisms linking RLS with EDS. The effect of RLS therapy on the measure of EDS also should be prospectively explored.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Work for this study was performed at 1st Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. This work was supported by the Grants of The Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic (2012/56-SAV-6 and 2012/10-UKBA-10) and by the Framework Programme for Research and Technology Development, Project: Building of Centre of Excellency for Sudden Cerebral Vascular Events, Comenius University Faculty of Medicine in Bratislava (ITMS:26240120023), cofinanced by European Regional Development Fund. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- AI

arousal index

- BMI

body mass index

- DI

desaturation index

- EDS

excessive daytime sleepiness

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- IQR

interquartile range

- mRS

modified Rankin Scale

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- PLMS

periodic limb movements of sleep

- RDI

respiratory disturbance index

- RLS

restless legs syndrome

- SDB

sleep-disordered breathing

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson KG, Johnson DC. Frequency of sleep apnea in stroke and TIA patients: a meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(2):131–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlesinger I, Erikh I, Nassar M, Sprecher E. Restless legs syndrome in stroke patients. Sleep Med. 2015;16(8):1006–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding Q, Whittemore R, Redeker N. Excessive daytime sleepiness in stroke survivors: an integrative review. Biol Res Nurs. 2016;18(4):420–431. doi: 10.1177/1099800415625285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks D, Davis L, Vujovic-Zotovic N, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients enrolled in an inpatient stroke rehabilitation program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(4):659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterr A, Herron K, Dijk DJ, Ellis J. Time to wake-up: sleep problems and daytime sleepiness in long-term stroke survivors. Brain Inj. 2008;22(7-8):575–579. doi: 10.1080/02699050802189727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden-Albala B, Roberts ET, Bazil C, et al. Daytime sleepiness and risk of stroke and vascular disease: findings from the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(4):500–507. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.963801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagel JF. Medications that induce sleepiness. In: Lee-Chiong TL, editor. Sleep: A Comprehensive Handbook. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2006. pp. 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klobučníková K, Šiarnik P, Čarnická Z, Kollár B, Turčáni P. Causes of excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with acute stroke--a polysomnographic study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(1):83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arzt M, Young T, Peppard PE, et al. Dissociation of obstructive sleep apnea from hypersomnolence and obesity in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(3):e129–e134. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wessendorf TE, Teschler H, Wang YM, Konietzko N, Thilmann AF. Sleep-disordered breathing among patients with first-ever stroke. J Neurol. 2000;247(1):41–47. doi: 10.1007/pl00007787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohayon MM, O'Hara R, Vitiello M. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome: a synthesis of the literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(4):283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Froese CL, Butt A, Mulgrew A, et al. Depression and sleep-related symptoms in an adult, indigenous, North American population. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(4):356–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celle S, Roche F, Kerleroux J, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of restless legs syndrome in an elderly French population: the synapse study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(2):167–173. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KW, Yoon IY, Chung S, et al. Prevalence, comorbidities and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in the Korean elderly population - results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(1 Pt 1):87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benediktsdottir B, Janson C, Lindberg E, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among adults in Iceland and Sweden: Lung function, comorbidity, ferritin, biomarkers and quality of life. Sleep Med. 2010;11(10):1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulfberg J, Nyström B, Carter N, Edling C. Restless legs syndrome among working-aged women. Eur Neurol. 2001;46(1):17–19. doi: 10.1159/000050750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulfberg J, Nyström B, Carter N, Edling C. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among men aged 18 to 64 years: an association with somatic disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Mov Disord. 2001;16(6):1159–1163. doi: 10.1002/mds.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brott T, Adams HP, Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20(7):864–870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sulter G, Steen C, De Keyser J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 1999;30(8):1538–1541. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guilleminault C, Brooks SN. Excessive daytime sleepiness: a challenge for the practising neurologist. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 8):1482–1491. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.8.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4(2):101–119. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specification. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Calhoun SL, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A. Excessive daytime sleepiness in a general population sample: the role of sleep apnea, age, obesity, diabetes, and depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4510–4515. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vgontzas AN, Legro RS, Bixler EO, Grayev A, Kales A, Chrousos GP. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness: role of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):517–520. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resta O, Foschino Barbaro MP, Bonfitto P, et al. Low sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in obese patients without obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. J Intern Med. 2003;253(5):536–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chokroverty S. Sleep disturbances in other medical disorders. In: Chokroverty S, editor. Sleep Disorders Medicine: Basic Science, Technical Considerations and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999. pp. 587–617. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santamaria J, Iranzo A, Ma Montserrat J, de Pablo J. Persistent sleepiness in CPAP treated obstructive sleep apnea patients: evaluation and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(3):195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20(9):705–706. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bassetti C, Mathis J, Gugger M, Lovblad KO, Hess CW. Hypersomnia following paramedian thalamic stroke: a report of 12 patients. Ann Neurol. 1996;39(4):471–480. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goyal MK, Kumar G, Sahota PK. Isolated hypersomnia due to bilateral thalamic infarcts. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21(2):146–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bliwise DL, Rye DB, Dihenia B, Gurecki P. Greater daytime sleepiness in subcortical stroke relative to Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2002;15(2):61–67. doi: 10.1177/089198870201500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tosato M, Aquila S, Della Marca G, Incalzi RA, Gambassi G. Sleep disruption following paramedian pontine stroke. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scammell TE, Nishino S, Mignot E, Saper CB. Narcolepsy and low CSF orexin (hypocretin) concentration after a diencephalic stroke. Neurology. 2001;56(12):1751–1753. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fulda S, Wetter TC. Is daytime sleepiness a neglected problem in patients with restless legs syndrome? Mov Disord. 2007;22(Suppl 18):S409–S413. doi: 10.1002/mds.21511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moller JC, Korner Y, Cassel W, et al. Sudden onset of sleep and dopaminergic therapy in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006;7(4):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kushida CA, Allen RP, Atkinson MJ. Modeling the causal relationships between symptoms associated with restless legs syndrome and the patient-reported impact of RLS. Sleep Med. 2004;5(5):485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kallweit U, Siccoli MM, Poryazova R, Werth E, Bassetti CL. Excessive daytime sleepiness in idiopathic restless legs syndrome: characteristics and evolution under dopaminergic treatment. Eur Neurol. 2009;62(3):176–179. doi: 10.1159/000228261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15(4):376–381. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basta M, Lin HM, Pejovic S, Sarrigiannidis A, Bixler E, Vgontzas AN. Lack of regular exercise, depression, and degree of apnea are predictors of excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with sleep apnea: sex differences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(1):19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]