Abstract

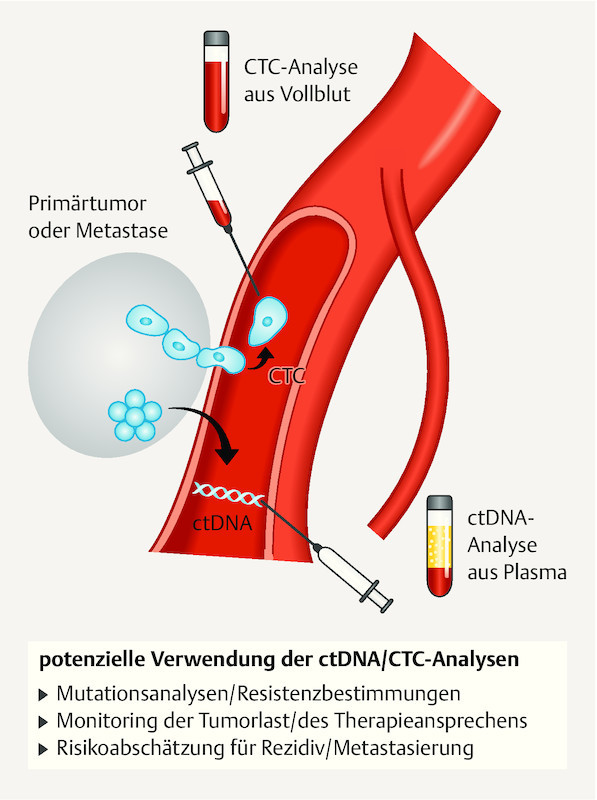

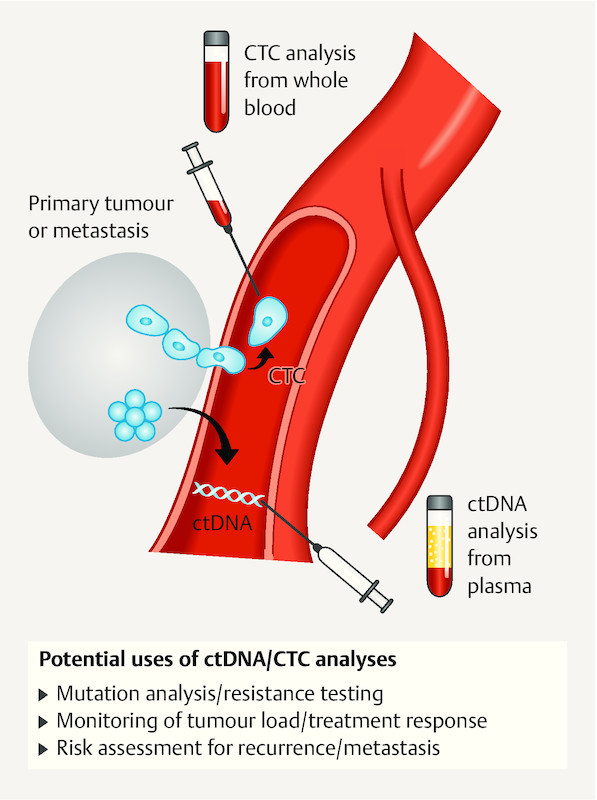

Dissemination of tumour cells and the development of solid metastases occurs via blood vessels and lymphatics. Circulating tumour cells (CTCs) and circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) can be detected in venous blood in patients with early and metastatic breast cancer, and their prognostic relevance has been demonstrated on numerous occasions. Repeated testing for CTCs and ctDNA, or regular so-called “liquid biopsy”, can be performed easily at any stage during the course of disease. Additional molecular analysis allows definition of tumour characteristics and heterogeneity that may be associated with treatment resistance. This in turn makes personalised, targeted treatments possible that may achieve both improved overall survival and quality of life.

Key words: breast, Her-2/neu (human epidermal growth factor recptor), hormonal receptor, mammary gland tumor, metastasis

Zusammenfassung

Die Streuung von Tumorzellen und Entstehung solider Metastasen findet sowohl über das Lymph- als auch das Blutsystem statt. Der Nachweis zirkulierender Tumorzellen (CTCs) und der zirkulierenden Tumor-DNA (ctDNA) im venösen Blut ist sowohl beim frühen als auch beim metastasierten Mammakarzinom möglich. Ihre prognostische Relevanz wurde bereits mehrfach bewiesen. Dabei ist die repetitive Untersuchung der CTCs bzw. ctDNA im Sinne einer regelmäßigen „liquid biopsy“ jederzeit und problemlos möglich. Durch die zusätzlichen molekularen Analysen ist es möglich, Tumorcharakteristika und ihre Heterogenität, die mit möglichen Resistenzen einhergehen, zu definieren. Dies ermöglicht den Einsatz einer personalisierten und zielgerichteten Therapie, um neben einem verlängerten Gesamtüberleben auch die Verbesserung der Lebensqualität zu erreichen.

Schlüsselwörter: Brust, Her-2/neu (humaner epidermaler Wachstumsfaktor-Rezeptor), Hormonrezeptor, Tumor der Brustdrüse, Metastase

Introduction

Thanks to numerous new treatment concepts and drugs the management of metastatic breast carcinoma (MBC) is in a state of continuous further development. Nevertheless MBC is still associated with high mortality and significant quality of life restrictions. Choosing between available treatment options is challenging for both doctor and patient alike. Current treatment regimens are tailored to tumour phenotype characteristics such as hormone receptor (HR) or HER2 status, which are usually determined at primary diagnosis. In the past, possible changes to tumour tissue phenotype were not detected and thus not taken into account even in the case of treatment failure. However, since tumour characteristics may change in the course of the disease, current treatment guidelines recommend the additional characterisation of e.g. solid metastases 1 . This recommendation however requires performing further invasive biopsies that are not always technically possible and may encounter limited patient compliance. Sequential HR and HER2 detection is thus generally not performed, meaning that tumour heterogeneity does not play a role in treatment decision-making 2 . As a consequence therapy remains nontargeted and potentially inefficient. The same applies to other tumour biomarkers.

With the aim of improving progression free survival (PFS) and quality of life (QoL) various study concepts are currently evaluating methods that would enable repeated and, most importantly, less invasive tumour characterisation. Constituting a so-called “liquid biopsy”, biomarkers such as circulating tumour cells (CTC) and circulating tumour DNA from peripheral venous blood are a promising alternative to formal biopsy for monitoring tumour characteristics (HR/HER2 status), treatment response and the course of disease.

The establishment of individual, personalised and therefore more effective treatment strategies is the ultimate goal.

Circulating Tumour Cells

Biological and clinical relevance

CTCs were described for the first time by Thomas Ashworth in 1869. Together with disseminated tumour cells (DTC) in bone marrow they are regarded as “minimal residual disease” and appear to be the source of distant solid metastases 3 . The prognostic significance of DTCs has been demonstrated for primary breast carcinoma 4 . A follow-up study has also shown that the demonstration of DTCs in bone marrow after completion of adjuvant systemic treatment is associated with higher recurrence risk 5 . DTCs would thus appear to be fundamentally suited to monitoring breast cancer and its prognosis. Like formal metastasis biopsy bone marrow aspiration, which is required for collecting DTCs, is an invasive diagnostic procedure that should not be performed more often than absolutely necessary. In contrast, analysis of CTCs only requires a few millilitres of venous blood and is thus a far less invasive, repeatable and practical alternative. CTCs can be detected in both primary and metastatic breast cancer. 65 – 85% of all patients with MBC have at least one, and 40 – 50% have at least five CTCs in a 7,5 ml sample of venous blood 6 , 7 .

Detection of CTCs also has prognostic relevance. As far back as 2004 Cristofallini and his research team showed that the finding of at least five CTCs in 7.5 ml of blood was associated with reduced PFS and overall survival (OS) in patients with MBS 7 . A study by Müller et al. in 2012 using the CELLSEARCH ® -Systems 8 and a pooled analysis of almost 2000 patients by Bidard and colleagues in 2014 9 showed similar results. Moreover, the SUCCESS study group demonstrated that the detection of CTCs both before and after adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with reduced disease-free survival and overall survival 10 . Most recently, in 2016, a pooled analysis of 3173 patients has concluded that the presence of CTCs at initial diagnosis of breast carcinoma is associated with worse prognosis 11 . To date however CTC analysis has not become part of, and these study findings have thus not yet influenced, routine clinical practice.

The role of CTC prevalence, dynamics and phenotype as predictive factors for disease prognosis and the treatment response, and the exact mechanisms of cell dissemination and metastasis formation are subject to current fundamental research and clinical study.

Numerous studies have shown that the HER2 and HR expression phenotype of solid metastases may differ from that of the primary tumour 12 , 13 . This phenotype discordance is already taken into account in clinical practice 1 . DTCs and CTCs also do not always demonstrate the exact phenotype of their primary tumour. Similar to the discordance of HR and HER2 expression of solid metastases, numerous studies have shown discrepant phenotypes between solid tumour tissue, i.e. primary tumour and/or metastases, and CTCs 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . A recent study showed that discordance of HER2 expression between primary tumour and CTCs was associated with the histological subtype and HR status of the primary tumour as well as with the absolute number of detected CTCs in 7.5 ml of blood 18 . Treatment decisions are however currently still governed by the phenotype of the primary tumour. At least one additional biopsy of a solid metastasis with immunohistological analysis for HR and HER2 expression is recommended in order to re-evaluate the treatment regimen and if necessary adapt it to a discordant phenotype 19 .

One study that is kinky relevant is the S0500 study of the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) that investigated the role of CTCs in MBC. No significant improvement of PFS or OS was achieved in patients with MBC with at least five CTCs at the beginning of treatment whose treatment regimens were changed after one cycle if there was no reduction in CTC count below 5 per 7.5 ml of blood. This very early regimen change did not improve prognosis, however it may have improved therapy guidance, reducing toxicity. In addition, the effectiveness of a new treatment regimen is perhaps questionable in the context of an indeed very early regimen change in the absence of a falling CTC count.

The role of CTCs and their phenotype discordance with respect to the primary tumour therefore continue to be further evaluated, especially since CTCs potentially constitute a simple, repeatable and non-invasive method of tumour characterisation. With this so-called “liquid biopsy” tumour heterogeneity and changes in tumour biology during the course of disease could potentially be analysed repeatedly. Adaption and potential optimisation of treatment strategies could then occur without the need for invasive biopsy (various) of solid metastases.

Current clinical studies

In the COMETI P2 study (Daniel F Hayes, M. D., University of Michigan Cancer Center) a CTC-ETI (endocrine therapy index) is calculated in order to predict response to hormone therapy. If prognosis for treatment response is poor chemotherapy would be favoured over endocrine therapy 20 . The CTC-ETI is calculated using quantitative CTC detection and CTC phenotype. The assumption is that high rates of ER and Bcl2 expression are associated with better response to endocrine therapy, while high rates of HER2 and Ki67 expression are associated with worse response. The results of this “proof of principle” study are intended to generate a further study whose aim would be to establish the CTC-ETI in HR positive, HER2 negative MBC.

Another current study concept is the CirCé01 study (Prof. Jean-Yves Pierga, Institut Curie, Paris) 21 . This study is analysing whether a treatment regime change in the absence of CTC reduction under systemic treatment has a positive effect on treatment response. Patients with MBC and disease progression after second-line chemotherapy and with at least 5 CTCs/7.5 ml blood are randomised 1 : 1 to a CTC or control arm. In the CTC arm CTC analysis is performed after the first cycle of each additional chemotherapy course. If there is inadequate reduction of CTCs the chemotherapy regime is changed. This clinical study is based on the assumption that the absence of CTC reduction after the first cycle of a given chemotherapy regime predicts inadequate treatment response. In the previously mentioned, similarly designed, randomised S0500 study no significant improvement in PFS or OS could be demonstrated for patients with MBC who had a chemotherapy regime change due to persistence of at least 5 CTCs in 7.5 ml of blood 21 days after treatment was commenced 22 . There is therefore a need for further clinical studies to more clearly define the role of CTCs in routine clinical practice.

The French STIC CTC study (Prof. Jean-Yves Pierga, Institut Curie, Paris) is a randomised trial where the choice of first-line treatment of HR positive MBC is made according to the number of detected CTCs. In the CTC arm patients with < 5 CTCs/7.5 ml blood receive endocrine treatment and those with ≥ 5 CTCs/7.5 ml are treated with chemotherapy. In the control arm the treatment regime is chosen by the principal investigator. The aim of this “non-inferiority” study is to prove that CTC-based treatment decision-making is not detrimental to PFS. The study aims to recruit a total of 994 patients in France 23 .

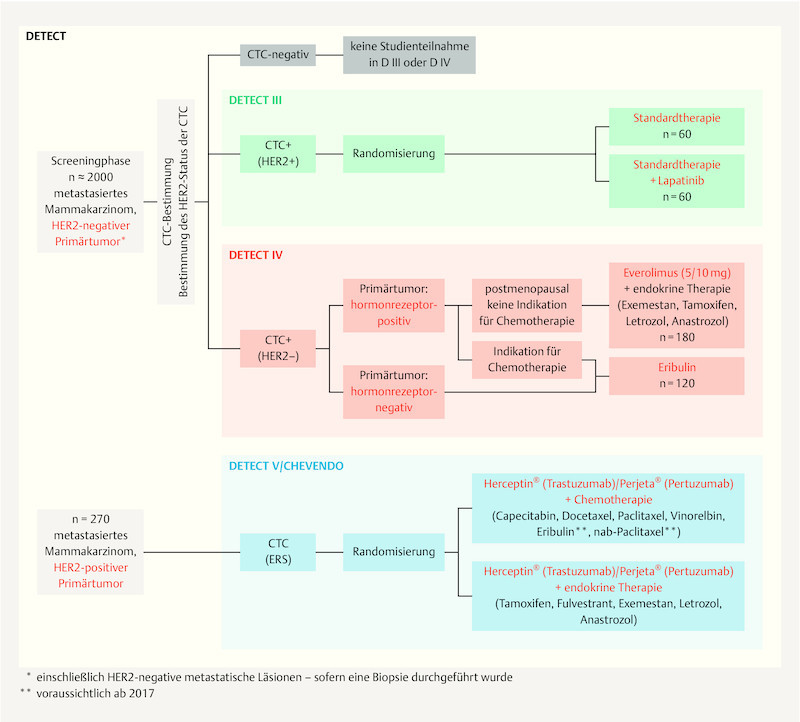

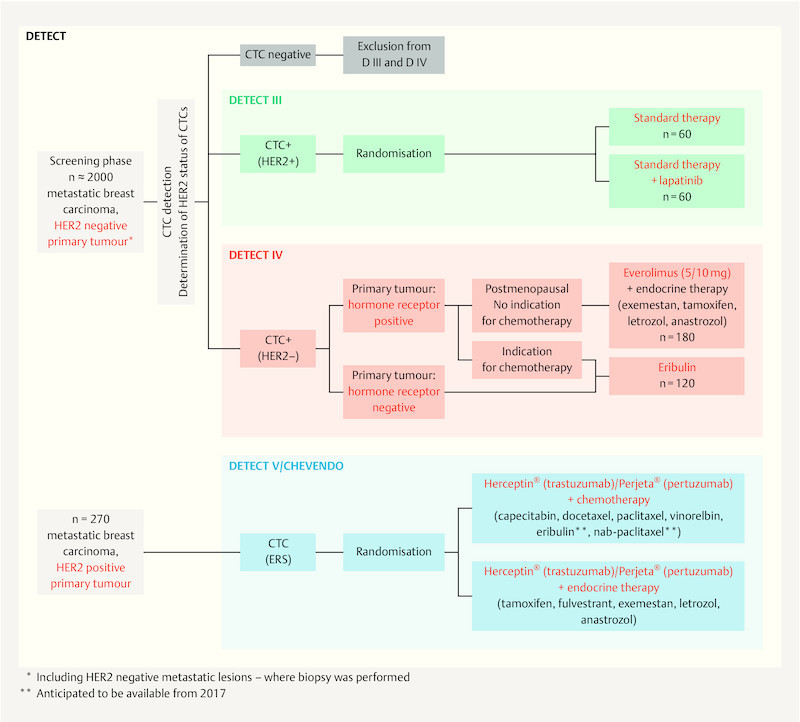

The DETECT study conducted by the DETECT study group is a further important related study concept ( Fig. 1 ). Treatment decisions in this worldwide largest study program on MBC are based on CTC detection and their phenotyping, with CTC HER2 expression having particular importance. Patients with HER2 negative MBC are screened for the presence of circulating tumour cells. Patients with HER2 positive CTCs enter the DETECT III study and are randomised to either standard chemotherapy or endocrine therapy with or without targeted HER2 treatment with lapatinib. Where only HER2 negative CTCs are present postmenopausal patients with HR positive MBC receive combination therapy with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus and endocrine therapy (DETECT IVa). If chemotherapy is indicated these patients and those with triple negative MBC are given monochemotherapy with the halichondrin B analogue eribulin (DETECT IVb). The DETECT III and DETECT IV studies are sponsored by the University Hospital Ulm represented by Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Janni, director of the University Womenʼs Hospital, Ulm. The head of clinical trials for the DETECT III and IV studies is Prof. Dr. Tanja Fehm (University Womenʼs Hospital, Düsseldorf). Both studies are planned to end in 2021.

Fig. 1.

The DETECT study concept. The figure shows the treatment concept for the DETECT III, IV and V studies.

The DETECT V study extends on DETECT III and IV evaluating treatment strategies in HER2 positive and HR positive MBC. Here too the detection of CTCs and evaluation of their potential predictive value play a central role. Patients are randomised 1 : 1 to receive dual targeted HER2 therapy with pertuzumab and trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy or endocrine therapy. The primary outcome of this phase III study is the safety and tolerability of both treatment arms (evaluated by the presence of and unwanted side-effects). In addition, using an “endocrine responsiveness score” (ERS), the study aims to derive a score based on CTCs and their oestrogen receptor and HER2 expression with which response to endocrine treatment could be predicted. Similar to the above-mentioned COMETI P2 study, this ERS is based on the assumption that strong oestrogen receptor expression is associated with a high response rate to endocrine therapy, and strong HER2 expression with a low response rate. The aim is to avoid chemotherapy – associated with worse effects on quality of life – in patients with potentially good response to an endocrine treatment regime. The DETECT V study is also sponsored by the University Hospital Ulm represented by Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Janni, director of the University Womenʼs Hospital, Ulm; head of clinical trails is Prof. Dr. Jens Huober (University Womenʼs Hospital, Ulm). Planned study end is 2021.

Analysing CTCs at molecular level is an important aspect in establishing them as prognostic and/or predictive markers. In this respect it must be particularly highlighted that DETECT study program is supported by numerous translational research projects. These attempt to identify further markers (or mutations) that may contain additional predictive and prognostic information, thus enabling a more specific tumour characterisation via “liquid biopsy”. One area of interest of the DETECT studyʼs translational research program is the analysis of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signal transduction pathway. Mutations in this area appear to be responsible for carcinogenesis and resistance to targeted HER2 therapies 24 , 25 . It has already been demonstrated that these mutations may occur discordantly between primary tumour and solid metastases 26 and, e.g. as gain-of-function mutations, may occur in metastases only later in the course of disease leading to acquired resistance to targeted HER2 treatments. As part of DETECTʼs translational research HER2 positive CTCs from patients with HER2 negative MBC are analysed for the presence of active PI3K-Akt mutations using SNaPshot technology. This may help explain disease progression in patients with HER2 positive CTCs despite the use of targeted HER2 treatment. Other translational research in the context of the DETECT study is investigating the expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers and tumour suppressor genes (e.g. LKB1) on CTCs, and the mechanisms of resistance to anoikis commonly found in tumour cells (programmed cell death due to loss of cell-matrix contact).

The DETECT study program also forms the basis of the current collaborative translational research project “DETECT CTC: Detection and molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells and cell-free nucleic acids in advanced breast cancer in the context of tumor heterogeneity”, which is supported by German Cancer Aid. The aim of the DETECT-CTC research projects is to use innovative methods and experimental approaches to isolate CTCs and circulating free nucleic acids in order to determine their suitability as a “liquid biopsy” for ascertaining the biological characteristics of advanced breast cancers and as predictive markers for treatment response and monitoring, with the ultimate aim of further optimising and personalising cancer treatment. Another important aspect is the comparison of mutations found in CTCs with circulating free nucleic acids. A further important aspect of DETECT-CTC is the clinical validation of selected biomarkers and test methods for the various breast cancer subtypes, for which all biomaterial collected during the DETECT studies program is used. Various subprojects of DETECT-CTC deal with the following topics:

Evaluation of DNA damage and repair markers on CTCs for the prediction of treatment response in triple-negative advanced breast cancer

Molecular characterisation (stem cell markers, markers for epithelial-mesenchymal transition) of heterogeneous CTC populations from metastatic breast carcinoma patients treated according to different strategies

Evaluation of the origins and molecular causes of resistance to endocrine therapy at the level of individual CTCs from patients with advanced breast cancer

Comparison of phenotypic expression of markers on CTCs, disseminated tumour cells from bone marrow, primary tumour and metastases in patients with metastatic breast cancer

Molecular characterisation of circulating free DNA and microRNA in blood and microDNA from CTCs in patients with metastatic breast cancer

Studies of the microevolution of resistant subclones in metastatic breast cancer through single cell analysis of CTCs

DETECT-CTC offers the unique possibility to analyse blood samples and genetic material collected repeatedly from patients with MBC in the course of their cancer treatment within the controlled environment of a large clinical study using the latest combined research methods, thus making an important contribution towards the establishment of individualised treatment strategies.

Circulating Tumour DNA

In addition to CTCs circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) is also the focus of current research. Circulating cell-free DNA (ccfDNA) was first described in healthy people over 70 years ago 27 . Increased amounts of ccfDNA are found in various physiological and pathological states such as inflammatory reactions, tissue trauma and cancers 28 , 29 . As is the case with CTCs, in 2002 Sozzi and research team demonstrated increased amounts of ccfDNA in patients with bronchial carcinoma compared to healthy controls 30 . As with CTCs, chemotherapy can reduce circulating DNA. This led to the assumption that ccfDNA, which contains tumour-specific changes and therefore constituting so-called ctDNA, could also be used as a biomarker or even for screening 31 .

Significant amounts of ctDNA has been detected in both early and metastatic breast carcinoma 32 . Increased amounts of ctDNA are associated with worse prognosis. Dawson and colleagues even postulated that monitoring ctDNA might be a more sensitive method of tumour load monitoring than CTCs or CA 15-3 33 . In contrast Heidary and colleagues found no correlation between tumour load and ctDNA 34 . Further studies are therefore necessary to define the role of ctDNA more precisely. As demonstrated for CTCs, however, it is not only the absolute amount of detected ctDNA that is relevant. Somatic mutations relevant to treatment response and disease prognosis can also be detected. Mutation rates concordant to those in tumour tissue have been found in the tumour suppressor gene TP53 and in PIK3CA, which plays an important role in the PI3K signal transduction pathway 35 , 36 . These results support the hypothesis that ctDNA reflects characteristics of the primary tumour on the one hand, and on the other hand can show characteristics of metastases that differ from the primary tumour.

The BELLE 2 and 3 studies are two important trials investigating the clinical relevance of ctDNA. The BELLE 2 study is a randomised trial analysing the efficacy of a combination treatment consisting of fulvestrant ± buparlisib, a PI3K inhibitor, in postmenopausal patients with HER2 negative and HR positive MBC with progression following treatment with an aromatase inhibitor. In a subgroup analysis it was shown that patients with proven PI3K mutation in their ctDNA benefited significantly from the combination therapy (median PFS of 7.0 vs. 3.2 months; p < 0.001). A similar survival advantage was not found in patients without ctDNA PI3K mutation (median PFS in both groups 6.8 months; p = 0.642) 37 . In contrast, in the BELLE 3 study patients were randomised after showing disease progression under endocrine combination therapy with an mTOR inhibitor 38 . Median PFS was 3.9 months in patients who received combination therapy with buparlisib plus fulvestrant, compared to median PFS of 1.8 months in patients who received only fulvestrant. In patients with a PIK3CA mutation PFS was 4.7 months in the buparlisib arm compared to 1.6 months in the placebo arm 39 .

Another important target in HR positive breast carcinoma is the oestrogen receptor α (ESR1) 40 . Increased rates of ESR1 mutations, which are associated with resistance to endocrine therapy, have been found especially in MBC 41 , 42 . In addition to solid tumour tissue these mutations can also be found in ctDNA 43 . In a secondary analysis of the BOLERO 2 study, baseline sample ctDNA from 541 postmenopausal patients with HR positive, HER2 negative MBC was analysed for two known ESR1 mutations (Y537S and D538G). 156 patients (28.8%) had at least one of the two mutations 44 and these were associated with reduced overall survival (32.1 months with wild type vs. 15.2 months with mutated alleles).

HER2 receptor expression also has prognostic relevance in MBC. In a recent study Ma et al. were able to demonstrate overexpression of HER2 on ctDNA analysis 45 . However ctDNA-based analysis showed HER2 overexpression in only 13 of 18 patients with HER2 positive MBC. Further studies are therefore needed to establish this method for detecting HER2 expression.

In summary, ctDNA analysis appears not only to allow monitoring of malignant disease but also to reflect important tumour characteristics. With this method it is possible to detect mutations that are important for identifying treatment resistance or which may constitute possible therapeutic targets. The PRAEGNANT network (Prospective Academic Translational Research Network for the Optimization of Oncological Health Care Quality in the Advanced Therapeutic Setting) is one of the worldwide largest networks focusing on acquiring ctDNA samples and other relevant biomarkers (CTCs, RNA, proteins etc.) in MBC. The study documents treatment course, treatment response, toxicity, comorbidities and quality of life. Aims include improving treatment of metastatic breast carcinoma, generating appropriate study designs and selecting patients for study participation 46 .

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the extraction of CTCs and ctDNA and their potential uses.

microRNA

In addition to DTCs, CTCs and ctDNA, microRNAs (miRNAs) are also playing an increasing role in research on minimal residual disease. miRNAs are small, non-coding molecules of approximately 21 – 25 nucleotide length that regulate the transcription of various genes through binding the complementary base sequences of not yet translated messenger RNA molecules 47 . Active miRNAs are those corresponding to whichever genes are being regulated in the cell at a given time.

miRNA is not only detectable in cells but similar to CTCs and ctDNA is found in peripheral blood. There are numerous different miRNAs of which only a few are thought to be associated with breast carcinoma. One of the focuses of research is to measure miRNAs repeatedly in the course of treatment. If an miRNA thought to be associated with breast carcinoma is raised at the start of therapy and subsequently falls, treatment response can be assumed. If the miRNA level rises, however, treatment nonresponse can be suspected. Currently treatment decisions cannot be made on the basis of miRNAs. Current research rather involves establishing which miRNAs can be viewed as “oncogenic” and which as “tumour suppressive”. The following two research projects are illustrative:

Roth et al. studied the potentially breast cancer-associated miRNAs miR10b, miR34a, miR141 and miR155 in the serum of women with breast cancer and in a healthy control group 48 . 89 breast cancer patients (59 = M0; 30 M1) and 29 healthy women were recruited in this pilot study with analysis using the TaqMan MicroRNA assay. The relative serum concentrations of total RNA (p = 0.0001) and miR155 (p = 0.0001) differed significantly between the M0 patients and the healthy control group. Using miR10b, miR34a and miR155 concentrations M1 patients could be differentiated from healthy women ( miR10b : p = 0.005; miR34a : p = 0.001; miR155 : p = 0.008).

In breast cancer patients changes in total amount of RNA and amounts of miR10b, miR34a and mitR155 correlated with the presence of manifest metastases (total RNA: p = 0.0001; miR100b : p = 0.01; miR34a : p = 0.003; miR155: p = 0.002). Also, M0 patients with more advanced stage tumours (pT3-pT4) had significantly higher amounts of total RNA and miR34a than patients with lower stage tumours (total RNA: p = 0.0001; miR34a : p = 0.01). The authors concluded that patients with tumour progression show a rise in tumour-associated RNA.

Madhaven et al. studied the miRNA in plasma of 40 patients with MBC using “TaqMan low density arrays” following previous validation studies on 237 MBC patients 49 . They were able to show that the detection of miR200a, miR200b, miR200c, miR210, miR215 and miR486 -5p was significantly associated with the occurrence of metastasis within two years of breast cancer diagnosis. They also identified 16 miRNAs that were significantly associated with OS and a further 11 associated with PFS.

Further studies are required both to identify MBC-associated miRNAs and to evaluate their role in the clinical course of breast cancer.

Conclusion

The analysis of relevant tumour characteristics and the evaluation of disease course and treatment response are immensely important for the prognosis and further treatment decision-making in MBC. In the context of potentially changing tumour characteristics repeated invasive examination of the primary tumour and/or solid metastases is not always a viable option. In contrast CTCs, ctDNA and miRNA, which contain relevant complimentary information, can be analysed as often as necessary in the form of a so-called “liquid biopsy”. This enables not the only potential monitoring of disease course and treatment response but also repeated tumour characterisation for future treatment decisions.

The long-term goal of CTC/ctDNA/miRNA-based evaluation of metastatic breast carcinoma is the establishment of personalised, targeted and thus efficient tumour therapy that increases PFS and/or OS and improves the quality of life of affected patients.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors state that no conflict of interest exists./ Die Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

References/Literatur

- 1.Aktuelle Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik und Therapie primärer und metastasierter Mammakarzinome der Kommission MAMMA in der AGO e.V. 2017. Online:http://www.ago-online.delast access: 09/2017

- 2.Gerlinger M, Rowan A J, Horswell S. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growth in cancer of the breast. Lancet. 1889;133:571–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun S, Vogl F D, Naume B. A pooled analysis of bone marrow micrometastasis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:793–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janni W, Vogl F D, Wiedswang G. Persistence of disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow of breast cancer patients predicts increased risk for relapse – a European pooled analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2967–2976. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fehm T, Muller V, Aktas B. HER2 status of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a prospective, multicenter trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:403–412. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bidard F-C, Peeters D J, Fehm T. Clinical validity of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2015;15:406–415. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller V, Riethdorf S, Rack B. Prognostic impact of circulating tumor cells assessed with the CellSearch System ™ and AdnaTest Breast ™ in metastatic breast cancer patients: the DETECT study . Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R118. doi: 10.1186/bcr3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bidard F C, Peeters D J, Fehm T. Clinical validity of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:406–414. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rack B, Schindlbeck C, Jückstock J.Circulating tumor cells predict survival in early average-to-high risk breast cancer patients J Natl Cancer Inst 2014106pii:dju066doi:10.1093/jnci/dju066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janni W, Rack B, Terstappen L W. Pooled analysis of the prognostic relevance of circulating tumor cells in primary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2583–2593. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y F, Liao Y Y, Yang M. Discordances in ER, PR and HER2 receptors between primary and recurrent/metastatic lesions and their impact on survival in breast. Med Oncol. 2014;31:214. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heitz F, Barinoff J, du Bois O. Differences in the receptor status between primary and recurrent breast cancer – the frequency of and the reasons for discordance. Oncology. 2013;84:319–325. doi: 10.1159/000346184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somlo G, Lau S K, Frankel P. Multiple biomarker expression on circulating tumor cells in comparison to tumor tissues from primary and metastatic sites in patients with locally advanced/inflammatory, and stage IV breast cancer, using a novel detection technology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1508-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munzone E, Nolé F, Goldhirsch A. Changes of HER2 status in circulating tumor cells compared with the primary tumor during treatment for advanced breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2010;10:392–397. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jäger B A, Finkenzeller C, Bock C. Estrogen receptor and HER2 status on disseminated tumor cells and primary tumor in patients with early breast cancer. Transl Oncol. 2015;8:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santinelli A, Pisa E, Stramazzotti D. HER-2 status discrepancy between primary breast cancer and metastatic sites. Impact on target therapy. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:999–1004. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schramm A, Friedl T WP, Schochter F. Association between HER2-phenotype on circulation tumor cells and primary tumor characteristics in women with metastatic breast cancer. AscoAnnuMeet. 2015;51:266. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanf V, Schütz F, Liedtke C. AGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer: Update. Breast Care (Basel) 2014;9:202–209. doi: 10.1159/000363551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paoletti C. Abstract OT1-3-01: Characterization of circulating tumor cells from subjects with metastatic breast cancer using the CTC-endocrine therapy index: the COMETI-P2-2012.0 trial. Cancer Res. 2013;73 (24 Suppl.):OT1-3-01. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Online:http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01349842last access: 09/2017

- 22.Smerage J B, Barlow W E, Hortobagyi G N. Circulating tumor cells and response to chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: SWOG S0500. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3483–3489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Online:http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01710605last access: 09/2017

- 24.Kataoka Y, Mukohara T, Shimada H. Association between gain-of-function mutations in PIK3CA and resistance to HER2-targeted agents in HER2-amplified breast cancer cell lines. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:255–262. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eichhorn P JA, Gili M, Scaltriti M. Phosphatidyinositol 3-kinase hyperactivation results in lapatinib resistance that is reversed by the mTOR/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor NVP-BEZ235. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9221–9230. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dupont Jensen J, Laenkholm A V, Knoop A. PIK3CA mutations may be discordant between primary and corresponding metastatic disease in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:667–677. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandel P M. Les acides nucleiques du plasma sanguin chez lʼhomme. CR Acad Sci Paris. 1940;142:241–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casciano I, Vinci A D, Banelli B. Circulating tumor nucleic acids: perspective in breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2010;5:75–80. doi: 10.1159/000310113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo Y M, Rainer T H, Chan L Y. Plasma DNA as a prognostic marker in trauma patients. Clin Chem. 2000;46:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sozzi G, Conte D, Leon M. Quantification of free circulating DNA as a diagnostic marker in lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3902–3908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leon S A, Shapiro B, Sklaroff D M. Free DNA in the serum of cancer patients and the effect of therapy. Cancer Res. 1977;37:646–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary R J. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:22ra224. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson S J, Rosenfeld N, Caldas C. Circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:93–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1306040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidary M, Auer M, Ulz P. The dynamic range of circulating tumor DNA in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:421. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madic J, Kiialainen A, Bidard F C. Circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells in metastatic triple negative breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2158–2165. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Board R E, Wardley A M, Dixon J M. Detection of PIK3CA mutations in circulating free DNA in patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:461–467. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0747-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baselga J, Im S A, Iwata H. PIK3CA status in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) predicts efficacy of buparlisib (BUP) plus fulvestrant (FULV) in postmenopausal women with endocrine-resistant HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer (BC): first results from the randomized, phase III BELLE-2 trial. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2015; San Antonio, TX, USA; Abstract S6-01

- 38.Di Leo A, Ciruelos E, Janni W. BELLE-3: A phase III study of the pan-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor buparlisib (BKM120) with fulvestrant in postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2- locally advanced/metastatic breast cancer (BC) pretreated with aromatase inhibitors (AIs) and refractory to mTOR inhibitor (mTORi)-based treatment. ASCO Annual Meeting 2015; Chicago, Il; Abstract TPS626

- 39.Di Leo A, Seok Lee K, Ciruelos E. BELLE-3: a phase III study of buparlisib + fulvestrant in postmenopausal women with HR+, HER2–, aromatase inhibitor-treated, locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer, who progressed on or after mTOR inhibitor-based treatment. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2016; San Antonio, TX, USA; Abstract S4-07

- 40.Yager J D, Davidson N E. Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:270–282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merenbakh-Lamin K, Ben-Baruch N, Yeheskel A. D538 G mutation in estrogen receptor-alpha: a novel mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6856–6864. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toy W, Shen Y, Won H. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1439–1445. doi: 10.1038/ng.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang P, Bahreini A, Gyanchandani R. Sensitive detection of mono- and polyclonal ESR1 mutations in primary tumors, metastatic lesions and cell free DNA of breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1130–1137. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chandarlapaty S, Chen D, He W. Prevalence of ESR1 mutations in cell-free DNA and outcomes in metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the BOLERO-2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1310–1315. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma F, Zhu W, Guan Y. ctDNA dynamics: a novel indicator to track resistance in metastatic breast cancer treated with anti-HER2 therapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:66020–66031. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fasching P A, Brucker S Y, Fehm T N. Biomarkers in patients with metastatic breast cancer and the PRAEGNANT study network. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2015;75:41–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee R C, Feinbaum R L, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roth C, Rack B, Muller V. Circulating microRNAs as blood-based markers for patients with primary and metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R90. doi: 10.1186/bcr2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madhavan D, Peng C, Wallwiener M. Circulating miRNAs with prognostic value in metastatic breast cancer and for early detection of metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:461–470. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]