Abstract

Objective

We explored factors associated with reasons women with urinary incontinence (UI) reported for not seeking treatment for their UI from a health care professional and whether reasons differed by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or education.

Methods

We analyzed questionnaire data collected from 1995 to 2005 in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. In visits 7–9, we elicited reasons women with UI reported for not seeking treatment and condensed them into: UI not bad enough, beliefs about UI causes (UI is a normal consequence of aging or childbirth), and motivational barriers (such as feeling too embarrassed). We used Generalized Estimating Equations and ordinal logistic regression to evaluate factors associated with these reported reasons and number of reasons.

Results

Of the 1339 women reporting UI, 814 (61.0%) reported they did not seek treatment for UI. The most frequently reported reasons were: “UI not bad enough” (73%), “UI is a normal part of aging” (53%), and “health care provider never asked” (55%). Women reporting daily UI had higher odds of reporting beliefs about UI causes (aOR UI 3.16, 95% CI 1.64, 6.11) or motivational barriers (aOR UI 2.36, 95% CI 1.21, 4.63) compared to women reporting less than monthly UI. We found no interactions by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or education and UI characteristics in reasons reported for not seeking UI treatment.

Conclusion

Over half of women who did not seek treatment for their UI reported reasons that could be addressed by public health and clinical efforts to make UI a discussion point during mid-life well-women visits.

Keywords: Urinary incontinence, treatment seeking, race/ethnicity, menopause

Introduction

About 45% of mid-life women report urinary incontinence (UI) occurring at least a few times per month, and about 15% report UI almost daily1. Many effective treatments are available to women for any severity of UI, including behavioral (e.g. limiting fluid intake or changing voiding habits), weight loss, pelvic floor muscle therapy, UI pessaries, medications and surgery2. In the community-based Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), we found that only about 40% of women who reported UI over 9 years sought treatment3. Reasons women reported for not seeking treatment in cross-sectional studies have included: feeling that their UI was not enough of a problem4–6, that UI was a normal consequence of childbirth or aging5,7,8, that they lacked knowledge about effective treatments,5,9 or were afraid of UI surgery7.

A previous longitudinal analysis showed that changes in frequency, type and duration of UI symptoms, as well as various physical, social, and psychological factors were associated with seeking UI treatment in mid-life women3. The objective of this study was to explore factors associated with reasons mid-life women reported for not seeking UI treatment over 9 years of follow-up in SWAN. We hypothesized that African American and Asian women and women of lower socioeconomic status and with lower educational attainment would be more likely than white women or women of higher socioeconomic status and educational levels to report reasons that would reflect barriers to care such as that their health care provider never asked about their UI.

Methods

Study Participants

In this prospective cohort study of women reporting UI in SWAN, we conducted analyses of questionnaire data collected from 1995 to 2005. SWAN is a multi-center, multi-racial/ethnic and multi-disciplinary longitudinal study of women undergoing the menopause transition (MT)10. Briefly, SWAN began with a cross-sectional survey of 16,065 community-dwelling women aged 40–55 years who were screened for eligibility for a cohort study at seven sites and were identified by random-digit-dialing and/or list-based sampling. From this group, each site then recruited approximately 450 women, consisting of about 50% white women and 50% women from one designated minority racial or ethnic group.

For the present analyses, we included data from baseline through visit 9 for all women from six of the seven clinical sites that collected data on treatment seeking (Pittsburgh, Oakland, Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, Boston) representing white, African American, Chinese and Japanese women. Inclusion criteria into the SWAN cohort attempted to capture women before or in the early stages of the MT: 1) age 42–52 years; 2) self-identification as African American at four sites, Japanese or Chinese at one site each, or white at all sites; and 3) ability to speak English, Japanese, or Cantonese. Exclusion criteria from the cohort identified women in whom the menstrual and hormonal characteristics and changes in these over the MT could not be tracked: 1) no menstrual period within three months before enrollment; 2) hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy prior to enrollment; 3) pregnant or lactating; or 4) using any hormonal medications at enrollment. All women consented for participation in SWAN, and the institutional review boards at each site approved the study.

Data Collection

SWAN collected measures of UI symptoms using questionnaires at each nearly annual visit. Based on responses to the question “In the last month, about how many times have you leaked urine, even a small amount?”, we defined daily UI for the response “almost daily/daily,” weekly UI for the response “several days per week,” and monthly UI for the response “less than one day per week.” We defined no clinically significant UI as “less than once per month” or none. We determined UI type by responses to the question “under what circumstances does leakage occur?” Stress UI was defined as occurring with “coughing, laughing, sneezing, jumping up and down, with physical activity”, while urge UI was defined by “when you have the urge to void and can’t reach the toilet fast enough.” We defined mixed UI when women responded positively to both circumstances of leakage. In some years, women reported on the bothersomeness of UI using a Likert scale. We considered women to have worsening UI when they reported an increase in frequency from one year to next, i.e. from no regular UI (after a previous report of UI) to monthly or more, from monthly to weekly or more, or from weekly to daily. We considered women to have improving UI when they reported a decrease in UI frequency from one year to the next.

SWAN participants with UI reported on whether they had sought treatment at baseline and in visits 7, 8 and 9 by responding yes or no to the question: “Have you ever discussed your leakage with a doctor, nurse, or other health care professional?” We included those who responded no to this question in our analyses.

In years 7, 8 and 9, we also elicited reasons women with UI reported for not seeking treatment by asking “Why have you not discussed your leakage with a doctor, nurse or other health care professional?:” Women could then select one or more reasons listed: “My problem is not bad enough to discuss it with a doctor, nurse or other health care professional,” “I don’t think there are any effective treatments for my leaking problem,” “Leaking urine is a normal part of getting older,” “Leaking urine is normal after having children,” “I am worried that I will be told I need surgery,” “I am too embarrassed about my leaking problem to bring it up at a visit with my doctor, nurse or other health care professional,” or “My doctor, nurse or other health care professional has never asked about my leaking problem.” To construct this questionnaire item, we used seven reasons previously reported in the literature5–9 and the Common-Sense Model of Illness Representations11; we then used this model to collapse the seven elicited reasons into three categories: 1) UI not bad enough (“my problem is not bad enough”), 2) beliefs about UI causes (“leaking urine is a normal part of getting older,” “leaking urine is a normal after having children”), and 3) barriers to motivation for UI treatment seeking (“I don’t think there are any effective treatments,” “I am worried I will be told I need surgery,” “I am too embarrassed about my problem,” and “My health care professional has never asked about my leaking problem”).

In addition to UI type, frequency and duration, our other main covariates were self-reported race/ethnicity, annual household income, level of difficulty paying for basics, and education level. We collapsed Chinese and Japanese women into “Asian” due to small numbers and because response patterns were similar between the two groups. Other covariates included psychosocial factors, such as depressive12 and anxiety symptoms13, social support/network14, experience of discrimination15, and physical/health-related factors such as self-assessed health, medical history and health care utilization. We calculated body mass index (weight in kg/height in m2) based on measurements obtained by calibrated balance beam scale (weight) and stadiometer (height).

Analyses

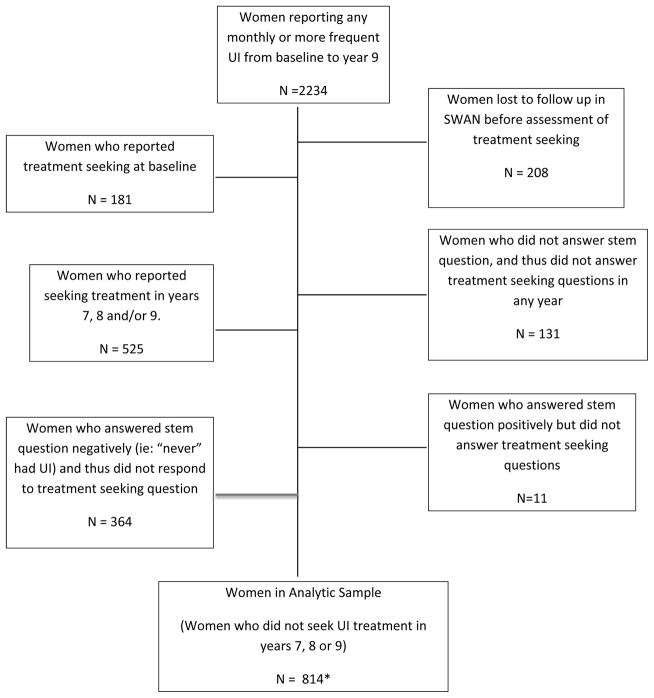

Women in our main analytic sample (N=814) were those who remained in the study, reported UI at any visit and responded negatively to having ever discussed their UI with a health care professional in years 7, 8 or 9 (Figure 1). A total of 364 women reported at least monthly UI at one or more visits but did not respond to the treatment-seeking questions because they responded negatively to the stem question “Have you ever leaked urine, even a small amount?” at all visits. We believe this group of women would have been unlikely to have sought treatment for a problem they did not recall having. While the main data analyses we present in this paper (Tables 1, 2 and 3) do not include this group of 364 women, we assessed whether including their data affected statistical inferences. In sensitivity analyses, we ran additional models in which we imputed that this group did not seek care because their “UI was not bad enough.” Because we found that point estimates were very similar with and without inclusion of this group, the results of analyses including these women are not presented.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation participants included in the main analytic sample of this study through annual follow up visit 9: incontinent women who reported that they did not seek treatment for their urinary incontinence.

*Includes 113 women who were censored in years 7 and 8 for non-response after these years/loss to follow up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Incontinent Women Who Did Not Seek Treatment for Urinary Incontinence by Reasons Reported for Not Seeking Treatment in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, 1995–2005; N = 814

| UI not bad enough | Beliefs about UI cause | Motivation barriers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N = 598 |

No N = 216 |

Yes N = 455 |

No N = 359 |

Yes N = 497 |

No N = 317 |

|

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White+ | 364 (60.9) | 103 (47.7) | 267 (58.7) | 200 (55.7) | 297 (59.8) | 170 (53.6) |

| African American | 102 (17.1) | 79 (36.6) | 74 (16.3) | 107 (29.8) | 82 (16.5) | 99 (31.2) |

| Asian | 132 (22.1) | 34 (15.7) | 114 (25.1) | 52 (14.5) | 118 (23.7) | 48 (15.1) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Annual Household Income§, n (%) | ||||||

| $35,000 and above | 495 (82.8) | 158 (73.1) | 369 (81.1) | 284 (79.1) | 405 (81.5) | 248 (78.2) |

| Below $35,000 | 79 (13.2) | 42 (19.4) | 70 (15.4) | 51 (14.2) | 69 (13.9) | 52 (16.4) |

| P value | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.56 | |||

| Difficulty paying for basics, n (%) | ||||||

| Very hard | 27 (4.5) | 18 (8.3) | 25 (5.5) | 20 (5.6) | 27 (5.4) | 18 (5.7) |

| Somewhat hard | 138 (23.1) | 63 (29.2) | 111 (24.4) | 90 (25.1) | 118 (23.7) | 83 (26.2) |

| Not very hard | 433 (72.4) | 134 (62.0) | 319 (70.1) | 248 (69.1) | 352 (70.8) | 215 (67.8) |

| P value | 0.01 | 0.97 | 0.69 | |||

| Education Level (baseline), n (%) | ||||||

| High School or Less | 82 (13.7) | 40 (18.5) | 72 (15.8) | 50 (13.9) | 75 (15.1) | 47 (14.8) |

| Some college or greater | 513 (85.8) | 170 (78.7) | 381 (83.7) | 302 (84.1) | 419 (84.3) | 264 (83.3) |

| P value | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.98 | |||

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||

| Single | 79 (13.2) | 26 (12.0) | 58 (12.7) | 47 (13.1) | 55 (11.1) | 50 (15.8) |

| Married, living as married | 416 (69.6) | 132 (61.1) | 317 (69.7) | 231 (64.3) | 353 (71.0) | 195 (61.5) |

| Divorced, widowed, separated | 101 (16.9) | 56 (25.9) | 78 (17.1) | 79 (22.0) | 87 (17.5) | 70 (22.1) |

| P value | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.02 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (sd) | 28.7 (7.2) | 29 (7.6) | 28.9 (7.5) | 28.5 (7) | 28.8 (7.4) | 28.7 (7.2) |

| P value | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.81 | |||

| Parity, n (%) | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 133 (22.2) | 36 (16.7) | 92 (20.2) | 77 (21.4) | 107 (21.5) | 62 (19.6) |

| Parous | 465 (77.8) | 179 (82.9) | 363 (79.8) | 281 (78.3) | 390 (78.5) | 254 (80.1) |

| P value | 0.09 | 0.65 | 0.51 | |||

| Number of doctor’s visits, mean (sd) | 4.0 (4.0) | 4.6 (4.9) | 4.0 (4.2) | 4.4 (4.4) | 4.0 (4.0) | 4.3 (4.7) |

| P value | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.34 | |||

| Proportion of years with women health visits, mean (sd) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) |

| P value | 0.89 | 0.57 | 0.28 | |||

| Depressive symptom score (0–20), mean (sd) | 8.1 (8.6) | 9.2 (9.4) | 9.2 (9.2) | 7.3 (8.3) | 8.9 (9.1) | 7.5 (8.3) |

| P value | 0.15 | 0.003 | 0.03 | |||

| Anxiety symptoms score (0–16), mean (sd) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.6 (2.5) | 2.5 (2.5) | 2.2 (2.2) | 2.4 (2.5) | 2.2 (2.2) |

| P value | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |||

| Experience of discrimination, n (%) | ||||||

| Sometimes/often any blatant | 95 (15.9) | 37 (17.1) | 75 (16.5) | 57 (15.9) | 87 (17.5) | 45 (14.2) |

| Sometimes/often any subtle | 158 (26.4) | 44 (20.4) | 123 (27.0) | 79 (22.0) | 132 (26.6) | 70 (22.1) |

| No significant mistreatment | 345 (57.7) | 135 (62.5) | 257 (56.5) | 223 (62.1) | 278 (55.9) | 202 (63.7) |

| P value | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.09 | |||

| Age at first report of UI, n (%) | ||||||

| Less than 47 years | 311 (52.0) | 70 (32.4) | 244 (53.6) | 137 (38.2) | 264 (53.1) | 117 (36.9) |

| 47 years or greater | 287 (48.0) | 146 (67.6) | 211 (46.4) | 222 (61.8) | 233 (46.9) | 200 (63.1) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Frequency of UI, n (%) | ||||||

| Daily | 26 (4.3) | 11 (5.1) | 27 (5.9) | 10 (2.8) | 29 (5.8) | 8 (2.5) |

| Weekly | 91 (15.2) | 28 (13.0) | 87 (19.1) | 32 (8.9) | 90 (18.1) | 29 (9.1) |

| Monthly | 384 (64.2) | 99 (45.8) | 284 (62.4) | 199 (55.4) | 314 (63.2) | 169 (53.3) |

| Less than monthly | 97 (16.2) | 75 (34.7) | 57 (12.5) | 115 (32.0) | 64 (12.9) | 108 (34.1) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Type of UI, n (%) | ||||||

| Stress | 243 (40.6) | 55 (25.5) | 192 (42.2) | 106 (29.5) | 206 (41.4) | 92 (29.0) |

| Urge | 119 (19.9) | 39 (18.1) | 70 (15.4) | 88 (24.5) | 94 (18.9) | 64 (20.2) |

| Mixed | 191 (31.9) | 66 (30.6) | 168 (36.9) | 89 (24.8) | 170 (34.2) | 87 (27.4) |

| Missing type | 45 (7.5) | 56 (25.9) | 25 (5.5) | 76 (21.2) | 27 (5.4) | 74 (23.3) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Bothersomeness of UI (0–10), mean (sd) | 3.5 (2.8) | 2.7 (2.8) | 3.6 (2.7) | 2.9 (2.8) | 3.7 (2.8) | 2.6 (2.7) |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | |||

| Duration of UI (years), mean (sd) | 5.9 (2.2) | 4.1 (2.7) | 6.2 (2.0) | 4.4 (2.5) | 6.1 (2.1) | 4.3 (2.6) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Mean (sd) person-years of UI frequency prior to not seeking treatment | ||||||

| Daily | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.1 (0.5) |

| Weekly | 0.9 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.6 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.6) | 0.6 (1.2) |

| Monthly | 3.8 (2.1) | 2.5 (2.0) | 3.9 (2.1) | 2.9 (2.0) | 3.8 (2.1) | 3 (2.1) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Change in frequency prior to seeking/not seeking treatment**, n (%) | ||||||

| UI worsened | 225 (37.6) | 118 (54.6) | 181 (39.8) | 162 (45.1) | 197 (39.6) | 146 (46.1) |

| UI unchanged with high variance | 238 (39.8) | 78 (36.1) | 172 (37.8) | 144 (40.1) | 188 (37.8) | 128 (40.4) |

| UI unchanged with low variance | 35 (5.9) | 4 (1.9) | 33 (7.3) | 6 (1.7) | 32 (6.4) | 7 (2.2) |

| UI improved | 100 (16.7) | 16 (7.4) | 69 (15.2) | 47 (13.1) | 80 (16.1) | 36 (11.4) |

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.006 | |||

| Mean (sd) person-years of UI type prior to not seeking treatment | ||||||

| Stress only | 3.4 (2.9) | 2.3 (2.5) | 3.4 (2.9) | 2.6 (2.7) | 3.4 (2.9) | 2.6 (2.7) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | |||

| Urge only | 1.3 (2.2) | 1.3 (2.1) | 1.1 (2.1) | 1.6 (2.3) | 1.2 (2.2) | 1.4 (2.2) |

| P value | 0.85 | 0.003 | 0.26 | |||

| Mixed | 1.8 (2.3) | 1.5 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.4) | 1.3 (2.0) | 1.9 (2.3) | 1.4 (2.0) |

| P value | 0.09 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | |||

| Change in UI type over years prior to seeking/not seeking treatment**, n (%) | ||||||

| Only stress | 95 (15.9) | 24 (11.1) | 72 (15.8) | 47 (13.1) | 79 (15.9) | 40 (12.6) |

| Only urge | 28 (4.7) | 14 (6.5) | 14 (3.1) | 28 (7.8) | 24 (4.8) | 18 (5.7) |

| Stress -> >Mixed | 238 (39.8) | 75 (34.7) | 187 (41.1) | 126 (35.1) | 199 (40.0) | 114 (36.0) |

| Urge -> >Mixed | 90 (15.1) | 43 (19.9) | 63 (13.8) | 70 (19.5) | 72 (14.5) | 61 (19.2) |

| Mixed or all other combinations | 147 (24.6) | 60 (27.8) | 119 (26.2) | 88 (24.5) | 123 (24.7) | 84 (26.5) |

| P value | 0.11 | 0.003 | 0.24 | |||

BMI, body mass index; UI, urinary incontinence

Columns may not add to 100% due to missing data.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or N (%) where n represents the number of women who reported this reason in any year, not the number of times reported because women may report the same reason in multiple years.

All variable values are from the first year that reason for not seeking treatment was reported unless otherwise specified.

P values comparing women reporting each reason at least once to women who never reported this reason

White refers to white, non-Hispanic.

Based on U.S. median household income in 1995 of $33,000.

Change in UI was calculated as: an increase in UI frequency between categories were assigned a value of +1, reports of no change were assigned a 0, and reports of a decrease in UI frequency between categories was assigned a value of -1. These were summed to define: worsening—overall score of greater than 0 (n = 343), improving—overall score of less than 0 (n = 116). A total of 316 women overall had a score of 0, indicating no change but reported many changes in frequency over the years of reporting, and 39 had a score of 0 but few changes in frequency.

Only stress at all visits before the visit reporting reason for not seeking treatment (n=119); Only urge at all visits before (n= 42). Stress -> mixed=reported stress UI only at first or more visits and then reported both stress and urge (n = 313). Urge -> mixed=reported urge UI only at first or more visits and then reported both stress and urge (n = 133). Mixed or other combinations—reported mixed at every visit or other combinations of reporting mixed and urge (n= 207).

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Demographic and Urinary Incontinence Characteristics associated with Reasons Women Reported for Not Seeking UI Treatment, Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, 1995–2005, N = 795

| Characteristic | UI not bad enough | Beliefs about UI cause | Motivation barriers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | (95% CI) | P-value | aOR | (95% CI) | P-value | aOR | (95% CI) | P-value | ||||

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White* | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | ||||||

| Black | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.78 | 0.0002 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.83 | 0.001 |

| Asian | 1.13 | 0.87 | 1.48 | 0.36 | 1.61 | 1.21 | 2.14 | 0.001 | 1.25 | 0.95 | 1.64 | 0.11 |

| Age (mean) | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.0004 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.94 | <0.0001 |

| Difficulty paying for basics | ||||||||||||

| Not very hard | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | ||||||

| Somewhat hard | 0.91 | 0.70 | 1.17 | 0.45 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.37 | 0.78 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 1.25 | 0.77 |

| Very hard | 0.91 | 0.55 | 1.49 | 0.69 | 1.19 | 0.70 | 1.99 | 0.52 | 1.06 | 0.65 | 1.74 | 0.81 |

| Education Level (baseline) | ||||||||||||

| High School or Less | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | ||||||

| Some college or greater | 1.21 | 0.89 | 1.65 | 0.22 | 1.07 | 0.77 | 1.49 | 0.69 | 1.02 | 0.75 | 1.40 | 0.88 |

| Number of years with UI | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.18 | 0.01 | 1.17 | 1.09 | 1.26 | <0.0001 | 1.18 | 1.10 | 1.28 | <0.0001 |

| Frequency of UI | ||||||||||||

| Less than monthly | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | ||||||

| Monthly | 2.08 | 1.33 | 3.25 | 0.001 | 2.02 | 1.32 | 3.08 | 0.001 | 1.94 | 1.31 | 2.85 | 0.0008 |

| Weekly | 2.20 | 1.55 | 3.13 | <0.0001 | 2.62 | 1.58 | 4.35 | 0.0002 | 2.54 | 1.54 | 4.19 | 0.0003 |

| Daily | 1.62 | 0.89 | 2.96 | 0.12 | 3.16 | 1.64 | 6.11 | 0.001 | 2.36 | 1.21 | 4.63 | 0.01 |

| Mean person-years of Stress only§ | 1.17 | 1.05 | 1.29 | 0.003 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.14 | 0.10 | ||||

| Mean person-years of Urge only§ | 1.14 | 1.02 | 1.27 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Mean person-years with Mixed§ | 1.18 | 1.06 | 1.33 | 0.003 | 1.10 | 1.02 | 1.19 | 0.01 | ||||

| Type of UI | ||||||||||||

| Stress only | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | ||||||

| Urge only | 0.93 | 0.61 | 1.42 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.61 | 1.23 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 1.10 | 0.19 |

| Mixed | 0.75 | 0.54 | 1.04 | 0.09 | 0.71 | 0.45 | 1.12 | 0.14 | 0.83 | 0.64 | 1.07 | 0.16 |

| Mean person years of monthly UI§ | 0.95 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 0.17 | ||||||||

| Experience of discrimination | 0.83 | 0.66 | 1.03 | 0.09 | ||||||||

Reported reason: UI not bad enough N = 580, Beliefs about UI cause N = 445, Motivation barriers N = 484

BMI, body mass index; UI, urinary incontinence; Data are adjusted odds ratios (aOR), 95% confidence interval (CI)

All values from the first year that reason for not seeking treatment was reported, unless otherwise specified.

All variables in the models are represented in the table; variables were selected by stepwise selection using 0.3 as entry criteria and 0.2 as retained criteria

White refers to white, non-Hispanic.

Women who report one UI type in all years: Stress only n = 298, Urge only n =158, mixed n = 257

Table 3.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Characteristics of Women with UI with the Number of Reasons Women Reported for Not Seeking Urinary Incontinence Treatment, Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, 1995–2005, N = 800

| Characteristic | aOR* | (95% CI) | P-value^ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| White* | 1.00 | reference | ||

| Black | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.73 | <.0001 |

| Asian | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.51 | 0.05 |

| Age (mean) | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.94 | <.0001 |

| Education Level (baseline) | ||||

| High School or Less | 1.00 | reference | ||

| Some college or greater | 1.06 | 0.84 | 1.35 | 0.63 |

| Difficulty paying for basics | ||||

| Not hard | 1.00 | reference | ||

| Somewhat hard | 1.05 | 0.72 | 1.52 | 0.82 |

| Very hard | 0.97 | 0.80 | 1.18 | 0.76 |

| Duration of UI | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.16 | 0.001 |

| Frequency of UI | ||||

| Less than monthly | 1.00 | reference | ||

| Monthly | 2.42 | 1.81 | 3.22 | <.0001 |

| Weekly | 2.92 | 2.04 | 4.17 | <.0001 |

| Daily | 2.92 | 1.81 | 4.70 | <.0001 |

| Mean person-years of Stress only | 1.15 | 1.06 | 1.25 | 0.001 |

| Mean person-years of Urge only | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.22 | 0.014 |

| Mean person-years of Mixed | 1.20 | 1.10 | 1.31 | <.0001 |

| Type of UI | ||||

| Stress only | 1.00 | reference | ||

| Urge only | 0.80 | 0.58 | 1.12 | 0.19 |

| Mixed | 0.78 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.05 |

BMI, body mass index; UI, urinary incontinence,

Data are adjusted odds ratios (aOR), 95% confidence interval (CI)

Ordinal logistic regression where ORs represent associations of reporting more reasons (i.e. 3+ reasons versus 2 reasons, or 2 reasons versus 1 reasons, or 1 reason versus no reasons).

All values from the first year that reason for not seeking treatment was reported unless otherwise specified.

All variables in the models are represented in the table; independent variables were selected by stepwise selection using 0.3 as entry criteria and 0.2 as stay criteria

White refers to white, non-Hispanic.

For each of the reasons women reported for not seeking treatment, we compared proportions of women who gave that reason to those who did not report that reason for not seeking treatment by such variables as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and level of education. Chi-square tests for homogeneity of proportions were performed for all categorical covariates. We also compared means of continuous variables by yes/no groups for each reason using t-tests (Table 1). In our multivariable analyses, for each of the three categories of reasons for not seeking treatment, because we had repeated binary responses (yes/no) for each woman in visits 7, 8 and 9, we used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to provide the associations between the probability of a yes response and the primary covariates of race, income, socioeconomic status and education level. We controlled for other baseline demographic characteristics. For our time-varying psychosocial, physical and health care variables, we used the value in the year each reason was first reported to evaluate associations. Finally, we assessed for interaction between the primary covariates (race, income, education) and duration and frequency of UI in the year prior to report of not seeking treatment and generated adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Finally, we examined factors associated with the number of reasons women reported for not seeking treatment, which we treated as an ordinal dependent variable using ordinal logistic regression. We selected our final independent variables for our models a priori based on the literature and from our analyses (Table 1) whenever p-values were ≤ 0.3. We selected our final models based on the Akaike Information Criterion16 for assessing model fit.

Results

In SWAN, 1339 women who reported UI from baseline through visit 9 remained in the study and answered the treatment seeking questions. Of these women, 814 (61%) reported they did not seek treatment for UI from a health care professional during follow up (51% of African American women with UI, 62% of white women with UI, 70% of Asian women with UI). Compared to women who sought UI treatment, women who did not seek treatment were more likely to be Asian, born outside the US and married and less likely to have anxiety symptoms or have seen a doctor for any reason.3 Of the women who did not seek treatment, 78% provided at least one reason, with most women (63%) reporting two to five reasons. The characteristics of women who did not seek treatment differed by the category of reason reported for not seeking treatment: UI not bad enough, beliefs about UI causes, and motivation barriers (Table 1). For example, African American women were least likely to report any of the reasons, while women with higher depressive symptom scores were more likely to report beliefs about UI causes and motivational barriers as reasons for not seeking treatment. Of the three categories of reasons for not seeking treatment, “UI was not bad enough” was the most frequently reported (73%). Beliefs about the cause of UI were also frequently reported as reasons (56%), in particular the belief that UI is a normal part of aging (53%). Among the motivational barriers to seeking UI treatment (61%), the individual reason most frequently reported was that their health care provider never asked (55%).

In multivariable analyses, we found that concurrent frequency and a longer duration of UI as measured by number years reporting UI and mean person years of UI, independent of UI type, were strongly associated with reporting “UI not bad enough,” beliefs about UI causes, and motivation barriers, (Table 2). When we examined models without frequency, type and duration of UI symptoms, we found that higher anxiety levels at the concurrent visit were weakly associated with reporting beliefs about UI causes (aOR 1.06 per unit increase in score, 95% CI 1.01, 1.12) while concurrent depressive symptoms (aOR 1.01 per unit increase in CES-D score, 95% CI 1.00, 1.03) and a higher BMI (aOR 1.02 per unit increase in BMI, 95% CI 1.00, 1.04) were associated with reporting motivational barriers.

Using an ordinal logistic regression model, we found that African American women had lower (aOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.47,0.73) and Asian women had higher (aOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.00, 1.51) estimated odds of reporting more reasons for not seeking treatment compared with white women (Table 3). Women with more frequent UI who did not seek treatment reported more reasons for not seeking treatment: women with daily UI had higher odds of reporting many reasons compared with those who reported monthly UI or less (aOR 2.92, 95% CI 1.81, 4.70). Women with mixed types of UI had lower odds of reporting multiple reasons for not seeking treatment compared to stress only or urge only UI (aOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.60,1.00). Bothersomeness and worsening or improving in UI symptoms of UI did not stay in our multivariable models suggesting no independent effect on reasons women reported for not seeking treatment.

Within the group of women who reported motivational barriers for seeking treatment, we were particularly interested in those who reported that “my health care professional has never asked about my leaking problem” because characterizing women most likely to identify this reason for not seeking treatment could raise clinician awareness about this vulnerable group. African American race (aOR 0.52, 95% CI 0.38, 0.71) and increasing age (aOR 0.91, 95% CI 0.88, 0.95) were associated with a reduced odds of reporting health care provider never asked about UI. Interestingly, women with weekly and monthly UI had the highest odds of reporting this reason (daily aOR 2.44, 95% CI 1.22, 4.89; weekly aOR 2.37, 95% CI 1.41, 4.00, monthly aOR 1.87, 95% CI 1.24, 2.82 compared to women whose UI was less than monthly).

In all of our models, for each category of reasons women reported for not seeking UI treatment, interactions between socioeconomic factors (race, level of education and difficulty paying for basics) and UI frequency and duration were not significant (p-value > 0.17, data not shown).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study with data from over 9 years, we found that frequency, type, and duration of UI symptoms were most strongly related to reasons incontinent women reported for not seeking UI treatment from a health care professional. Women whose UI duration was longer (more years of reporting UI), were more likely to report any reason for not seeking treatment, i.e. putting off finding help for long-standing UI seemed to require explanation. Not surprisingly, women with less frequent UI had higher odds of reporting that their “UI was not bad enough,” while women with more frequent UI had higher odds of reporting reasons related to their beliefs about the cause of UI or motivation barriers to treatment seeking.

We used the Common-Sense Model of Illness Representations11 to construct our self-administered questionnaire and evaluate our data. This model indicates that cognitive understanding and affective interpretation of illness may affect care seeking for that illness. First, women must acknowledge their UI symptoms as a problem. We found that more women who reported that they did not seek treatment for UI because their UI was not bad enough had infrequent UI symptoms, and this did not differ by race, education level or socioeconomic status. Second, judging that the causes of UI are outside of personal control reduced self-efficacy to seek treatment. Believing that UI is a normal consequence of aging was the second most frequently reported reason for not seeking UI treatment, regardless of UI frequency or duration. Third, when a woman felt her medical provider was not interested in her problem or felt too embarrassed to bring it up, reporting UI required greater individual motivation5,7–9. Of particular importance to clinicians, more than half of incontinent women in SWAN reported that their health care providers did not inquire about UI, the third most frequently reported reason for not seeking UI treatment.

While African American women were equally unlikely to seek UI treatment, consistent with the literature17, in our study, they were about half as likely to report any reason for not seeking treatment compared with white women, and they reported fewer reasons overall. While incontinent white women with lower incomes and education were the most likely to drop out of our study sample, African American women were more likely to answer “no” to our stem question “have you ever leaked urine”, despite having past reports of UI3. Studies that have evaluated why African Americans are less likely to participate in research have cited a higher rate of distrust in medicine and research within African American communities, regardless of socioeconomic status or education level18,19. Given that the African American women in this study is participated and remained in SWAN for at least 7 years, distrust is an unlikely explanation for why they were less likely to disclose reasons for not seeking treatment.

Asian women in our study who reported UI had the lowest rate of seeking UI treatment. They were more likely to report beliefs about the causes of UI as the reason for not seeking treatment (69.1% Chinese and 68.4% of Japanese) and to report that their health care provider never asked about their UI, compared to white and African American women. Chinese and Japanese cultures share some similarities that affect health care seeking behaviors. For example, Asian women are less likely to disclose health problems related to the reproductive and genitourinary systems, prefer to seek help within their own communities, and judge health problems as having underlying causal explanations that are more holistic than mechanistic20–22

The main strengths of our study included following a racially/ethnically diverse sample of community-dwelling, mid-life women from across the U.S. for nearly a decade across their MT. The longitudinal design allowed prospective assessment that provides unique information by minimizing the recall bias found in prior cross-sectional studies on this topic4–6. We were able to evaluate patterns of UI such as changes in frequency, duration, and type over nearly a decade before women reported the reasons for not seeking treatment. Additionally, we could examine temporal associations between other time-varying factors, such as the development of depressive or anxiety symptoms, and the reasons women reported for not seeking treatment.

Our study also had some limitations. First, while SWAN’s UI questions were similar to those in validated questionnaires 23,24, validated UI questions were not available at SWAN’s initiation. Second, despite our sample being community-based, our results may not be generalizable. SWAN participants are a distinct subset of women who had to meet strict inclusion criteria early in their MT. Most important, those who remained in the study for over 9 years are a unique group of women who actively engage in regular research visits and thus are more likely to be health aware. These analyses only evaluated reasons for why women did not seek UI treatment from a health care professional; they did not include seeking help for UI from other sources. Finally, the reasons we elicited for why women may not seek treatment may not be reflective of all reasons or the complexity of reasons women might report for not seeking UI treatment.

Conclusion

The results of our investigation are important for public health, and for the clinical care of mid-life women. First, the reasons women have for not seeking treatment were mostly related to the frequency and duration of their UI, and this did not differ among African American, Asian and white women. Second, neither socioeconomic status nor educational level were related to the reasons women reported for not seeking UI treatment. More than half of mid-life incontinent women in our cohort reported erroneous beliefs about UI causes; in particular, Asian women were most likely to report that UI is a normal consequence of aging. Clinicians should work to dispel this potential barrier to UI treatment in all women, but perhaps particularly among patients from Chinese or Japanese cultural backgrounds. Second, independent of race, educational level and socioeconomic status, motivational barriers to seeking UI treatment included that health care providers did not inquire about UI. This is of particular importance because women with UI may have lower self-esteem and sense of mastery25 which may reduce incontinent women’s agency in interacting with her health care provider. Public health and clinical efforts directed at making UI a standard element in the review of systems and a point for discussion and education in mid-life and older well-woman exams could minimize this particular barrier reported by the women in our study.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support and Acknowledgements

Support for this study was through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) Grant:

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the ORWH (Grants NR004061; AG012505, AG012535, AG012531, AG012539, AG012546, AG012553, AG012554, AG012495). The content of this article manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK, NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 – present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA – Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 – present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 – 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL – Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 – present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 – 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser – Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles – Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY – Carol Derby, PI 2011 – present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010 – 2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 – 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry – New Jersey Medical School, Newark – Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 – 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD – Winnie Rossi 2012- present; Sherry Sherman 1994 – 2012; Marcia Ory 1994 – 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD – Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 – 2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 – 2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Waetjen LE, Liao S, Johnson WO, et al. Factors associated with prevalent and incident urinary incontinence in a cohort of midlife women: a longitudinal analysis of data: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:309–18. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Practice B-G the American Urogynecologic S. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 155: Urinary Incontinence in Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e66–81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waetjen LE, Xing G, Johnson WO, Melnikow J, Gold EB Study of Women’s Health Across the N. Factors associated with seeking treatment for urinary incontinence during the menopausal transition. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1071–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgio KL, Ives DG, Locher JL, Arena VC, Kuller LH. Treatment seeking for urinary incontinence in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1994;42:208–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein M, Hawthorne ME, Engeberg S, McDowell BJ, Burgio KL. Urinary incontinence. Why people do not seek help. J Gerontol Nurs. 1992;18:15–20. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19920401-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seim A, Sandvik H, Hermstad R, Hunskaar S. Female urinary incontinence--consultation behaviour and patient experiences: an epidemiological survey in a Norwegian community. Fam Pract. 1995;12:18–21. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peake S, Manderson L, Potts H. “Part and parcel of being a woman”: female urinary incontinence and constructions of control. Med Anthropol Q. 1999;13:267–85. doi: 10.1525/maq.1999.13.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branch L, Walker L, Wetle T, DuBeau C, Resnick N. Urinary incontinence knowledge among community-dwelling people 65 years of age and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1994;42:1257–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holst K, Wilson PD. The prevalence of female urinary incontinence and reasons for not seeking treatment. N Z Med J. 1988;101:756–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sowers M, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, et al. SWAN: A Multicenter, Multiethnic, Community-Based Cohort Study of Women and the Menopausal Transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey JL, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 175–88. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leventhal H, Nerenz D. The assessment of illness cognition. New York: Wiley; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–283. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1226–35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DSM, Jackson JS, editors. Self, Stress, and Physical Health: The role of group identity. Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akaike H. Information measures and model selection. Int Stat Inst. 1983;22:277–91. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger MB, Patel DA, Miller JM, Delancey JO, Fenner DE. Racial differences in self-reported healthcare seeking and treatment for urinary incontinence in community-dwelling women from the EPI study. Neurourol Urodyn. 30:1442–7. doi: 10.1002/nau.21145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbie-Smith G, Flagg EW, Doyle JP, O’Brien MA. Influence of usual source of care on differences by race/ethnicity in receipt of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:458–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pang EC, Jordan-Marsh M, Silverstein M, Cody M. Health-seeking behaviors of elderly Chinese Americans: shifts in expectations. Gerontologist. 2003;43:864–74. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.6.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim W, Keefe RH. Barriers to healthcare among Asian Americans. Soc Work Public Health. 2010;25:286–95. doi: 10.1080/19371910903240704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo GJ, Le M-N, Oda AY. Handbook of Asian American health. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown JS, Bradley CS, Subak LL, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple test to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:715–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Buckwalter JG, Burchette RJ, Nager CW, Luber KM. Epidemiology of prolapse and incontinence questionnaire: validation of a new epidemiologic survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:272–84. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Consequences of incontinence for women during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2013;20:915–21. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318284481a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]