Abstract

The purpose of memory is to guide current and future behavior based on previous experiences. Part of this process involves either discriminating between or generalizing across similar experiences that contain overlapping conditions (such as space, time, or internal state), which we often conceptualize as “contexts”. In this review, we highlight major challenges facing the field as we attempt a neuroscience-based approach to the study of context and its impact on learning and memory. Here, we review some of the methodologies and approaches used to investigate context in both animals and humans, including the neurobiological mechanisms involved. Finally, we propose three tenets for operationalizing context in the experimental setting: 1) contexts must be stable over time along an experiential dimension; 2) contexts must be at least moderately complex in nature and their representations must be modifiable or adaptable, and 3) contexts must have some behavioral relevance (be it overt or incidental) so that its role can be measured.

Keywords: context, items, hippocampus, associations, binding

What Constitutes a Context?

Contextual information plays a key role in investigations of learning and memory, but is notoriously difficult to operationalize and study. A typical view of context is that it sets up expectations or contingencies that themselves can serve as ways of organizing information or as cues for retrieval. Take, for example, the “butcher on the bus” phenomenon often used to exemplify familiarity-based recognition memory [1]. A person (e.g., the butcher) on the bus looks familiar, but without the relevant features of the familiar context (e.g., the butcher shop), the identity of this individual can be difficult to retrieve. This example illustrates the power of context in providing a rich set of retrieval cues, which can range from an emotional state to a physical space. In the laboratory setting, context is present in all of our experiments, even if it is not parametrically varied or specifically examined. When given a yes/no recognition test for a list of words, the question is not whether “window” has ever been seen, but rather whether it was seen in the context of the experiment or a particular study list. When asked for a free associate of “hand”, it is not an entirely free-association, but an association bound by or at least informed by the context of the study episode. For example, if the study list contained semantically related words such as “time, dial, alarm”, one might freely associate with “clock” whereas if the list contained words such as “arm, leg, body”, one might respond with “finger”. Every time we repeat items on a study list, each experience is different from the last despite the fact that we call it a “repetition” as the context has changed. Even if the same items are presented before and after, eliciting a repetition of a sequence of events, the “temporal context” is different and the second set of items will quite likely be viewed as a “second set”, altering the context in which they are being viewed. Thus, the test participant is now different and the experiential history is different, leading in some ways to a different context. Yet, at the same time, these potentially minor alterations may well be subsumed over a more general context common to the events. Thus, in addition to space and time, experiential history, emotional state, motivational state, hormonal state, circadian rhythm, attentional fluctuations, and many other factors contribute to context. Given the ever present and pervasive nature of “context” in the study of memory (and more broadly, any cognitive or behavioral task), it can be difficult to isolate and define in operational terms what makes up a context in any situation.

The hippocampus has long been implicated in contextual processing, with data from lesions and electrophysiological recordings in rodents to functional neuroimaging in humans. A review of this literature reveals a multitude of paradigms and approaches to investigating context, with as many variations on what constitutes context. Generally, as we will discuss at length, a common thread appears to be the processing of associations. Here, we review how context has been examined in studies of episodic memory and attempt to distill the key components of context and the issues that need to be addressed to make progress in understanding context, its instantiation in the brain, and the role it plays in memory.

First, we survey approaches to operationalizing and studying context in the literature and then evaluate the neurobiological mechanisms involved in representing context. Next, we explore the notion that simple perceptual information (be it driven from the external environment or from retrieval or imagery) could be driving many of the effects observed in extant studies, which complicate our attempts to isolate broader contextual representations. To make progress in this domain, future studies must go further to mitigate the possibility that observed effects are purely from associative memory or from perceptual confounds. Finally, we propose three tenets for operationalizing context in the experimental setting: 1) contexts must be stable over time along an experiential dimension; 2) contexts must be at least moderately complex in nature and their representations must be modifiable or adaptable, and 3) contexts must have some behavioral relevance (be it overt or incidental) so that their role can be measured. Thus, while we believe that there is a meaningful representation to “context” in the brain, more research is necessary to establish and differentiate contextual processing from an association of features, no matter how complex.

It is important to note that in this discussion, we are not attempting to draw lines around what context is in an absolute sense. Indeed, the elements of an experience that form a context can vary, leaving ample room for gray areas. The three tenets we describe are rather intended to aid in an effective operational definition, which can make for clearer contrasts in experimental designs. Thus, we urge the reader to bear in mind that we are considering context as a gradient or continuum, and are offering avenues of thought that can assist in determining which experimental conditions and contrasts might optimize the operationalization of context to better understand its role in learning, memory, and behavior.

Cornucopia of Contextual Conditions

Context has been operationalized and studied in a variety of different ways in the extant literature. One very common experimental design used in rodent studies is contextual fear conditioning. Briefly, this paradigm introduces an aversive stimulus, typically a shock, to an animal in a particular chamber. Later, the animal is returned to that chamber in the absence of the aversive stimulus (sometimes different chambers with no aversive pairings are also used as control conditions). The freezing response is measured, which is taken as evidence that the animal remembers the negative association between the chamber and the aversive stimulus [2]. The amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex are often found to be critical for this type of fear conditioning [3] (more on the roles of these regions in the Neurobiological Mechanisms Underlying Context section). Though this is a simple operationalization of a context, it satisfies basic conditions of stable low-frequency information (i.e., the spatial layout of the chamber) and behavioral relevance. However, it must be noted that the presence or absence of freezing does not necessarily inform one as to what an animal remembers. For example, lesions to the amygdala, which eliminate freezing, do not necessarily eliminate other indices of fear memory (e.g., avoidance) in conditioned animals [4]. Despite complications in interpreting freezing, this paradigm has been a powerful tool for assessing the contributions of different brain regions to context-dependent memory. For instance, it was recently demonstrated that freezing behaviors can be ‘transferred’ to an unconditioned chamber by optogenetically reactivating certain hippocampal neurons that were active in a conditioned chamber [5].

As with fear conditioning, many experimental uses of context hinge on “where + what” associations. Importantly, this is not simply memory for spatial locations or for items, but memory for specific item-location pairings. These paradigms have emphasized the importance of medial temporal lobe regions in establishing item-location or item-scene associations across rodents [6–8] and primates [9,10]. Similar approaches have been taken in humans, such as objects encoded against a background image [11,12] or in different on-screen locations [13,14]. In this type of experimental design, non-human animals are often tasked with exhibiting a specific behavior in the event of specific pairings of items and locations to demonstrate memory for spatial context. This response-contingency approach is also used in humans, though some studies have queried subjects more subjectively by asking them to indicate the extent to which they “recollect” the spatial context in which an item was encountered [15]. Beyond static images, spatial context has also been widely used in navigational paradigms, in rodents [16] and humans alike [17–19].

Associations between “when + what” have also been studied. Memory for time has been tested at a variety of scales, from the general time of year to the specific position of an events in a sequence [20–22]. Sequence memory has been widely used due to the relative ease of manipulating it experimentally. In these paradigms, animals learn a sequence of items (e.g., specific odors) and are subsequently tasked with exhibiting specific behaviors to discriminate between learned sequences and novel sequences, some of which highly overlap with the memorized sequence [23]. Similar approaches have been used in nonhuman primates [24] and humans [25–27]. In addition, more unstructured investigations of temporal context have been used. For example, it has been reliably found that list items that were learned within temporal proximity are often recalled together [28]. This may involve the mnemonic binding of one item to the next across a temporal gap, and the linking of these events then occur based on a temporal context [28–30].

Beyond simpler associations between an item and either a spatial or temporal dimension, several experiments have examined more complex “where + when + what” contextual influences. Clayton and Dickinson [31] showed that scrub jays could distinguish which food they cached (worms vs. nuts), where in the cage, and how long ago (hours vs. days). Similar paradigms have been used in rats [32], nonhuman primates [33], and humans [34]. A major appeal of these types of experiments is that they better approximate the way contexts are typically encountered, represented, and used by an animal. That is, it is more ecologically valid to set up conditions in which the operational context is spatiotemporal rather than only spatial or temporal in nature. By setting up a multifaceted experimental context, one can begin to understand and perhaps disentangle the ways that different aspects of that context influence its overall neural representation, and the impact of each aspect on the animal’s behavior.

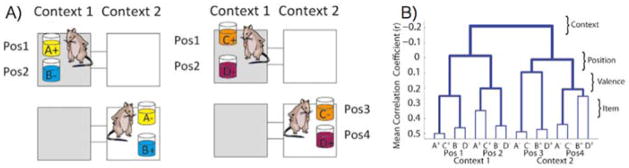

In a recent and highly systematic approach, Eichenbaum and colleagues used a context-guided object association task in rodents, which is feature-rich to the extent that it can be reasonably compared to human experiences [35,36]. In this paradigm, rats learn context-dependent rules for associating particular items with reward. More specifically, the contexts are defined as different chambers with distinct visual and tactile features. In addition, there are two items (differently scented cups of sand), each occupying a particular location. These elegant studies used pattern similarity analysis across neuronal ensembles (akin to representational similarity analysis of human fMRI data) to look for evidence of a hierarchical organization to the information content (Figure 1). Using a hierarchical model, context (the chamber) emerged as the dominant source of variance with the other dimensions (location, reward contingency, and item) nested heavily within context [35]. Items, for example, existed, but only within the population of neurons selected by the context.[35]. Items, for example, existed, but only within the population of neurons selected by the context.

Figure 1.

Adapted from McKenzie et al. [60]. A) Rats must discriminate between two items given the constraints of context and item location in order to obtain a reward. B) Neurons in the hippocampus showed activity consistent with a hierarchical model with item, valence, and position nested within context.

Though memory of an item in a particular set of spatiotemporal circumstances may at first glance seem to encompass context, there have been a host of other, more abstract approaches. For example, studies have operationalized context as colors associated with words or objects [37,38], background music [39], odors [40], and even the mood of participants [41]. Though semantic memory (i.e., general memory for facts) has often been described as “noncontextual” [42], several recent studies have explicitly studied a type of semantic context. Of particular note is the Context Maintenance and Retrieval (CMR) model [30]. Based on the Temporal Context Model (TCM; [28]) which attributes a shared context to temporally proximal items, CMR accounts for semantic relationships between items in addition to temporal overlap. Just as items from similar temporal contexts (points in time) are clustered at recall, free recall of word lists features semantic clustering, or coincident recall of items with related meaning [43,44]. Semantically associated information often shares spatiotemporal features (e.g., a shovel near a rake), which may itself be sufficient to converge into the type of associative representation that qualifies as a context. In this way, the items can be integrated over time, creating a context from the pre-experimental context and the newly learned context.

Thus, there are many ways that context memory has been operationalized. For example, item memory is often sharply contrasted with context memory or item-in-context memory. However, it is not clear that item memory can ever be free of contextual factors. As Yee & Thompson-Shill [45] have noted, “the concepts themselves are inextricably linked to the contexts in which they appear”. In other words, it is difficult to imagine a “no context” condition because concepts (items) cannot be meaningfully separated from the contexts in which they appear. Retrieving an item will re-activate the representation of context(s) associated with that item. Thus, attempting to fully dissociate or orthogonalize purely contextual from purely item-related aspects of the experience may not be a fruitful direction. A more tangible goal may be to define the conditions that can be used to examine contextual influences and the neural mechanisms that represent them, while acknowledging that much like the rest of cognitive psychology and neuroscience, process purity is difficult to isolate. This argument does not negate the usefulness of the term “context”, nor does it imply that there are not components of the representation that should be best thought of as representing the context. As long as context can be operationally defined and systematically varied in an experimental setting, the term remains useful and provides explanatory power.

Neurobiological Mechanisms Underlying Context

The hippocampus has long been implicated in processing contextual information [46–48]. Conditioned responses (e.g., freezing) in response to contextual stimuli (e.g., test chambers) that have been associated with foot shock are eliminated with lesions to the hippocampus. Furthermore, infusions of scopolamine (a cholinergic agonist) into the hippocampus have implicated acetylcholine in contextual fear conditioning [2,49,50]. Hippocampal function in rodents is often characterized by the stability of place cells - hippocampal neurons that selectively fire at a particular location in the environment [51]. When place fields remain stable, they “reflect the integration of stable background information, sensory information, internal state, and behavioral outcome expectancies within a spatial framework as function of time” [52]. Changes in the modality of cues [53], the motivational state [54], or the behaviors needed to perform the task [55] result in alterations of the place fields, a process known as remapping [56]. Remapping reflects changes in the context-defining features of events, utilizing boundaries in space and time to isolate one event from the next. [46–48]. Conditioned responses (e.g., freezing) in response to contextual stimuli (e.g., test chambers) that have been associated with foot shock are eliminated with lesions to the hippocampus. Furthermore, infusions of scopolamine (a cholinergic agonist) into the hippocampus have implicated acetylcholine in contextual fear conditioning. Hippocampal function in rodents is often characterized by the stability of place cells - hippocampal neurons that selectively fire at a particular location in the environment. When place fields remain stable, they “reflect the integration of stable background information, sensory information, internal state, and behavioral outcome expectancies within a spatial framework as function of time”. Changes in the modality of cues, the motivational state, or the behaviors needed to perform the task result in alterations of the place fields, a process known as remapping. Remapping reflects changes in the context-defining features of events, utilizing boundaries in space and time to isolate one event from the next.

These mechanisms are still largely unknown, but the detection of changes in space or time that constitute those boundaries may rely on pattern separation processes in the dentate gyrus subfield of the hippocampus [57]. In contrast, previously encoded representations may be reactivated by partial cues via the recurrent collaterals in the CA3 subfield of the hippocampus [57–59]. A resulting mismatch between the current (or expected) conjunction of contextual features and the current input may give rise to a boundary shift, resulting in a new representation [52]. Additionally, theta and gamma rhythms modulate activity in the hippocampus, providing an important mechanism for temporally organizing context information into separable events [60,61]. The binding of these elements into sustained and reinstatable activity constitutes the neural representation of context.[57]. In contrast, previously encoded representations may be reactivated by partial cues via the recurrent collaterals in the CA3 subfield of the hippocampus. A resulting mismatch between the current (or expected) conjunction of contextual features and the current input may give rise to a boundary shift, resulting in a new representation. Additionally, theta and gamma rhythms modulate activity in the hippocampus, providing an important mechanism for temporally organizing context information into separable events. The binding of these elements into sustained and reinstatable activity constitutes the neural representation of context.

Similarly, one of the major theories of medial temporal lobe function has focused on the Binding of Items in Context (BIC), which emphasizes the localization of information about objects (projecting from the “what” visual stream) to the perirhinal cortex and the information about contexts (notably, spatial processing projecting from the “where” visual stream) to the parahippocampal cortex [38,62]. These two sets of projections converge in the hippocampus, which binds them into a unique representation of the item in context. In support of this theory, Ranganath and colleagues draw upon a set of tasks in humans that rely on a “remember” (i.e., an indication that the participant remembers specific details from the original presentation of the item) vs. “know” (i.e., an indication that the participants knows that they encountered the item earlier, but cannot remember any specific details of the original event) response, or a source memory judgment (wherein a participant must identify a specific attribute from the original presentation, such as the voice of the speaker who said the word or the side of the screen that the word was presented on) [63,64]. In activating the hippocampus for “remember” responses, there is evidence to support the idea that the hippocampus is binding the items and contexts (sources and episodic details of the original event). Such binding can be extended to other domains. For example, emotional context has been established by the pairing of pictures with arousing or neutral sounds [65] or pairing emotional background pictures and emotional context sentences with neutral pictures or words [66,67]. We should note, however, that while this contrast contains clear aspects of context or source, it is not necessarily limited to or specific to context. [38,62]. These two sets of projections converge in the hippocampus, which binds them into a unique representation of the item in context. In support of this theory, Ranganath and colleagues draw upon a set of tasks in humans that rely on a “remember” (i.e., an indication that the participant remembers specific details from the original presentation of the item) vs. “know” (i.e., an indication that the participants knows that they encountered the item earlier, but cannot remember any specific details of the original event) response, or a source memory judgment (wherein a participant must identify a specific attribute from the original presentation, such as the voice of the speaker who said the word or the side of the screen that the word was presented on). In activating the hippocampus for “remember” responses, there is evidence to support the idea that the hippocampus is binding the items and contexts (sources and episodic details of the original event). Such binding can be extended to other domains. For example, emotional context has been established by the pairing of pictures with arousing or neutral sounds or pairing emotional background pictures and emotional context sentences with neutral pictures or words. We should note, however, that while this contrast contains clear aspects of context or source, it is not necessarily limited to or specific to context.

While there is little debate regarding the importance of the hippocampus for contextual aspects of memory, there is debate regarding its exclusivity. Animals with entorhinal lesions showed a disruption in conditioning when contexts were switched, comparable to those with hippocampal lesions [68], and activity in entorhinal cells rapidly respond to changes in context and drive context-specific fear memory [69]. The entorhinal cortex has direct projections into both the dentate gyrus and the CA1 subfields of the hippocampus, creating a circuit critical for retrieval of context [70]. Specifically, proximal CA1 is preferentially connected with the medial entorhinal and retrosplenial cortices that are sensitive to an animal’s position in space [71], while distal CA1 is connected to the lateral entorhinal cortex and perirhinal cortex, which are important for processing objects [71,72]. Further upstream, the postrhinal cortex (analogous to the parahippocampal cortex in humans) is thought to provide input to the hippocampus regarding space as part of the “where” pathway. Lesions to this region have also been shown to impair contextual fear conditioning [73] and an inability to discriminate between different contexts [74]. In addition, a recent model suggests that the retrosplenial cortex has a critical role in forming associations between the individual sensory stimuli that form an environment, while the postrhinal cortex maintains the relationship or change in the meaning of these contextual stimuli [75]. Finally, bidirectional prefrontal-hippocampal interactions may support context-guided memory, wherein the hippocampus sends contextual information to the prefrontal cortex, which guides the successful retrieval of memories in the hippocampus [76]. This network has also been observed in human fMRI studies with strong contextual associations activating the parahippocampal cortex, retrosplenial cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex [68], and activity in entorhinal cells rapidly respond to changes in context and drive context-specific fear memory. The entorhinal cortex has direct projections into both the dentate gyrus and the CA1 subfields of the hippocampus, creating a circuit critical for retrieval of context. Specifically, proximal CA1 is preferentially connected with the medial entorhinal and retrosplenial cortices that are sensitive to an animal’s position in space, while distal CA1 is connected to the lateral entorhinal cortex and perirhinal cortex, which are important for processing objects. Further upstream, the postrhinal cortex (analogous to the parahippocampal cortex in humans) is thought to provide input to the hippocampus regarding space as part of the “where” pathway. Lesions to this region have also been shown to impair contextual fear conditioning and an inability to discriminate between different contexts. In addition, a recent model suggests that the retrosplenial cortex has a critical role in forming associations between the individual sensory stimuli that form an environment, while the postrhinal cortex maintains the relationship or change in the meaning of these contextual stimuli. Finally, bidirectional prefrontal-hippocampal interactions may support context-guided memory, wherein the hippocampus sends contextual information to the prefrontal cortex, which guides the successful retrieval of memories in the hippocampus. This network has also been observed in human fMRI studies with strong contextual associations activating the parahippocampal cortex, retrosplenial cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex.

Returning to the context-guided object association task in rodents [35], item representations existed in the hippocampus, but only within the population of neurons selected by the context. Subsequent work extended this beyond the hippocampus to the adjacent medial temporal lobe cortices, where variations on this theme were observed. Whereas perirhinal and lateral entorhinal cortex feature item-level information above spatial position in the hierarchy, the opposite is true of parahippocampal and medial entorhinal cortex [36]. Interestingly, all regions examined featured global context atop the hierarchy – something many models would not have predicted for regions such as perirhinal and lateral entorhinal cortex. Thus, independent of any minute differences in preference for specific features across different cortical regions, the entire medial temporal lobe appears to be sensitive to context above all else.[35], item representations existed in the hippocampus, but only within the population of neurons selected by the context. Subsequent work extended this beyond the hippocampus to the adjacent medial temporal lobe cortices, where variations on this theme were observed. Whereas perirhinal and lateral entorhinal cortex feature item-level information above spatial position in the hierarchy, the opposite is true of parahippocampal and medial entorhinal cortex. Interestingly, all regions examined featured global context atop the hierarchy – something many models would not have predicted for regions such as perirhinal and lateral entorhinal cortex. Thus, independent of any minute differences in preference for specific features across different cortical regions, the entire medial temporal lobe appears to be sensitive to context above all else.

Accounting for context in sensory cortices

Despite the range of approaches to investigating context, there is a complication regarding the activation of low-level perceptual features found in many task designs. The crux of the issue is that activity in certain brain areas – for instance, hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex – during recollection is often taken as evidence of contextual processing in those regions. However, this use of reverse inference relies on the assumption that these areas’ contributions uniquely support contextual representations, which becomes apparent when retrieving contextual details. However, despite the rising popularity of information-based pattern analysis techniques, there have been no systematic investigations that have tested the possibility that these medial temporal lobe regions simply reflect a convergence of low-level sensory input.

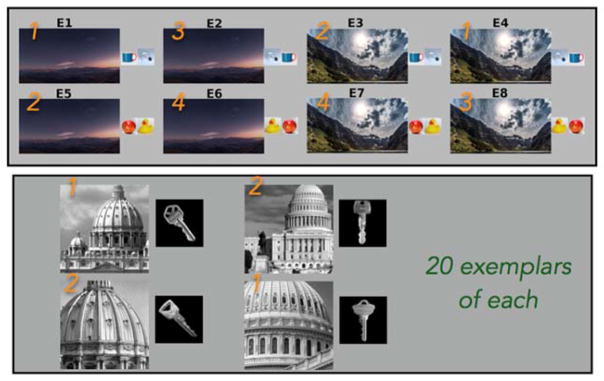

A recent study [79] addressed this issue directly by designing an fMRI study (Figure 2) modeled after the studies by Eichenbaum and colleagues [35]. Briefly, trials began with the start of one of two full-screen movie clips (time-lapse nature scene) to provide an occasion-setter that might mimic the rodent entering one of two chambers. After several seconds, two small objects briefly appeared, one after the other, in the middle of the screen. Thus, a longer-duration, large stimulus that sets the scene for a location in space (desert at night vs. mountains at day) is used as a context and small, transiently-presented objects are used as items. Through trial and error, specific button presses (1–4) were learned to correspond to a particular item-in-order-in-context combination, ensuring the targeted complex representations were acquired. Representational similarity analysis revealed strong sensitivity to context in parahippocampal and retrosplenial cortices and more modest context sensitivity in the hippocampus. The retrosplenial cortex was additionally sensitive to item-in-context conjunctions and the degree of fit to this item-in-context matrix correlated with behavioral performance across subjects. This finding is largely consistent with prior reports of contextual representations in these cortical regions during memory retrieval. However, a control analysis surprisingly revealed that primary visual cortex was sensitive not only to context and items-in-context, but also items-in-order-in-context and it too correlated strongly with behavior. Moreover, a whole brain searchlight analysis corroborated the result, revealing robust sensitivity to all aspects of the task throughout the ventral visual stream. A second experiment used “context” and “item” stimuli that were nearly indistinguishable based on low-level visual properties. When this confound was eliminated and context (and item) could no longer be easily distinguished by low-level visual cues, all evidence for information pertaining to context was eliminated from the retrosplenial cortex, the MTL and primary visual cortex. Thus, what appeared to be a prominent contextual code in the MTL was driven heavily, if not exclusively, by low-level perceptual features rather than some general sense of context. Though one could argue that the way context was operationalized in this paradigm is impoverished, it is no more so than the vast majority of studies in humans, and thus carries strong implications for how such data can be interpreted moving forward.

Figure 2.

Adapted from Huffman & Stark. In Experiment 1 (top panel), two contexts (sunset or mountains) contained two sets of objects in AB or BA order. Participants learned which of 4 responses (orange numbers) corresponded to each of these 8 permutations. In experiment 2 (bottom panel), the low-level perceptual complexity was matched across multiple exemplars from two contexts (left=Basilica, right=U.S. Capitol) and multiple exemplars from two object sets (house or car keys).

A possible interpretation of these findings is that primary visual cortex represented contextual information in this study. Though this would be an unorthodox view, we note that there is evidence for memory-related processing in sensory cortices [80]. For example, primary auditory cortex is known to represent associative memory for shock stimuli and specific tones [81]. Primary visual cortex has been demonstrated to be sensitive to recognition of associations in the form of visual sequences, even in the absence of conscious awareness [82]. Moreover, simple visual recognition and behavioral habituation occurs as a function of synaptic changes in primary visual cortex [83]. Simultaneous recordings from primary visual cortex and hippocampus have demonstrated “place cell” activity in visual areas [84]. Even more strikingly, “place cell” activity in primary visual cortex has even been found to precede such activity in the hippocampus [85]. Thus, sensory areas are not only sensitive to content we often reserve for medial temporal lobe regions, but this content can be quite complex and detailed.

There are two major avenues for explaining these types of results: 1) primary sensory cortices are capable of representing different facets of context (as discussed above), and/or 2) what we sometimes interpret as representations of broad context in the medial temporal lobe may be driven by highly distinct low-level sensory features, perhaps especially in the case of visual stimuli. To some extent, and depending on the nature of the stimuli in question, both of these possibilities may be at play in a given experiment. In any case, the results of Huffman and Stark [79] emphasize the need to carefully consider the influence of low-level features and computations outside the medial temporal lobe. To this point, one needs only to consider that, despite profound amnesia resulting from medial temporal lobe resection, patient H.M. [86] was capable of encoding and understanding context. Further, the question is raised of exactly how privileged or special contextual representations are. It may be the case that complex modality-specific representations of context exist in low-level sensory regions, which happen to converge downstream with other complex representations in regions such as retrosplenial and parahippocampal cortices. Beyond the Huffman and Stark [79] study, this finding raises interesting questions about the extent to which prior studies demonstrating information about rooms and positions in the hippocampus and adjacent cortices [e.g. 35,36] may also have been possibly present in upstream sensory regions. Indeed, the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe cortices receive input from every sensory modality, and as Aly & Turk-Browne [87,88] have shown, medial temporal lobe representations may depend heavily on which sensory stimuli are subject to attention. Finally, although sensory reactivation has been reported during recall in fMRI paradigms [89], these issues make it extremely difficult to disentangle evidence for memory-based reactivation from simple representation of task details in sensory cortices in many paradigms. This confound may particularly be an issue if stimuli or even components of those stimuli are displayed on the screen at the time a memory-guided decision is being made.

Taken together, we do not take these pieces of evidence to suggest that the hippocampus and adjacent cortices do not represent contextual features. Rather, we argue that care should be taken when drawing strong interpretations about obtaining a readout of context from canonically “memory-related” brain regions, or any other regions of the brain receiving complex and highly-processed information. Moreover, a more fruitful line of thinking may be less about regional involvement and more about the conditions one needs in order to confidently manipulate context or decode contextual representations. There are multiple possible avenues one can take to mitigate these concerns. For instance, one could study context in the absence of overt pairings of highly distinct sensory stimuli, such as has been done in studies of temporal memory [27,90,91]. Another simple approach is the inclusion of control conditions that attempt to account for low-level sensory differences in the stimuli comprising the context, as was attempted in the second experiment of Huffman & Stark [79]. Yet another approach would be to experimentally vary the similarity of contextual features, testing the extent to which brain regions track immediate sensory differences versus a more abstract sense of context. Finally, one might be able to vary “context” by cueing the participant that a contextual shift has occurred (rule set B is now in place) but forcing the maintenance of this context to be accomplished internally (e.g., a brief light signals the shift of context that is then maintained for some time until the light signals a shift again, akin to occasion setting in Pavlovian conditioning [92].

Three tenets for investigating context

Our review of the literature emphasizes the variety of paradigms and theoretical approaches to investigating context. On the face of it, the examples of “context” discussed above may seem very different. The seemingly disparate use of the term has been noted in the past [93], and there have been calls for clarity in the use of the term [94]. Our aim here is not to define context per se, but to consider the necessary conditions for examining context such that the conclusions can account for a wide variety of findings, from place field remapping in rodents to post-traumatic stress reactions triggered by a sound or location. Thus, we propose three tenets for operationalizing context in the experimental setting: 1) contexts are stable over time along an experiential dimension (space, state, order, motivation, task demands, etc.), relative to the individual events that occur within the context; 2) contexts are associatively complex and evolving, constituting more than simple 1:1 associations and changing their association properties with every presentation; and 3) contexts must have some behavioral relevance (be it overt or incidental), such that behavior is either explicitly or implicitly contingent upon or modified by the contextual information (e.g., background or spatial configuration, emotional or motivational state). In other words, the influence of a context on behavior should be measurable in contrast with the absence of that context, or in a different context.

In the following sections, we will first step through the proposed tenets, elaborating on the meaning and implications of each. We then discuss application of these tenets to the existing literature, surveying their relation to prominent paradigms such as contextual fear conditioning in rodents and object-scene associations in humans. As we noted at the outset, our goal is to provide a framework for operationalizing and studying context in the experimental setting rather than defining context per se.

Tenet 1: Context is stable over time

We posit that context is a relatively stable state (or set of conditions), wherein events or items can transiently occur. Polyn and colleagues [30] define context as “a pattern of activity in the cognitive system, separate from the pattern immediately evoked by the perception of a studied items, that changes over time and is associated with other coactive patterns”, which is a clear defining feature of context. The elements of a context that are activated by some stimulus or event, tend to stay active past the time this stimulus leaves the environment, and are thus associated with the features of studied material. This definition primarily uses temporal dynamics to define “context” as it “must reflect the features and statistical properties of studied items, integrate information over long time scales, and return to a prior state, given the recall of an item” [30]. We note that we are not arguing that this stability must be permanent or absolute (as will be discussed below, in Tenet 2). Rather, the very straightforward suggestion is that a context is stable with respect to events or items that occur within it. This condition is important, because without this relative stability, the putative context could not serve to organize the way events or items are represented. Though it is difficult (if not impossible) to control what factors will comprise a context for a given participant, an emphasis on stability in an experiment mitigates the possibility that phasic items (e.g., specific objects) contaminate the more global sense of context (e.g., a virtual environment).

Tenet 2: Context is associatively complex and evolving

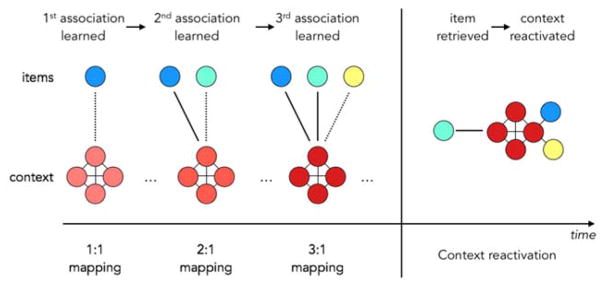

We posit that a context can be thought of as a complex associational structure, where multiple items are associated with a single context. Under models based on Hebbian learning and spreading of activation (or at least back-of-envelope versions of such models), reactivating the context necessarily activates, at least to an extent, every item that has ever been paired with this context. While somewhat hyperbolic, this idea demonstrates that the shared associations between items and contexts cannot be represented in terms of simple 1:1 mapping, but rather as n:1 mapping where n is >1. In other words, multiple items must be associated with a context in order for it to be operationalized as a context instead of a simple association.

We can illustrate a contextual representation as a set of nodes that become activated under a specific set of conditions (Figure 3). These nodes may reflect dimensions of space, time, motivation, or other dimensions reflected by the environment or internal state. Within this contextual representation, individual items or events may occur. When a single item is associated with a context, it is a simple 1:1 mapping. But with additional items, or with other events paired with the same, relatively stable context, the mapping complexity increases and the contextual representation becomes more stable. Reactivation given any of the previously paired cues re-instantiates the context as a stable state which then facilitates the retrieval of all prior associates.

Figure 3.

When an item is associated with a contextual representation, an association is formed, which is then reactivated when that context is later reinstated in the presence of a new associate. Over repeated presentations, the contextual representation is stable (the four red nodes remain consistent), but new associates can be added, resulting in the evolution of this context over time. The strength of the association between the item to the context is modulated by its behavioral relevance.

For example, if we present a set of items on a red background, followed later by the same set on a blue background, context can be defined in terms of red/early vs. blue/late in this experimental setup. If we randomly and repeatedly present items A, B, and C on a red background and items D, E, and F on a blue one, context is simply red vs. blue, as red was stable across some number of items (i.e., was selectively associated with this set of items) and blue was stable across another set of items. Conversely, if A is always shown on a red background, B on blue, C on purple, D on gray, etc. the color background is no longer particularly contextual as it is only co-active with its uniquely associated object. Context here is an evolving state that encompasses the presentation of various items within a context to the formation and stabilization of a given context over time.

We also suggest that contextual representations must be evolving, such that they can change over the course of multiple presentations. For example, in contextual fear-conditioning, the chamber likely represents a context to the rodent prior to the foot shock, but is undeniably altered following the conditioned event. We argue that the chamber warranted a contextual representation at both time points, but that it changed as function of experience. By the same token, in our example above, when item A was first presented against the red background, the association between items and background is still ambiguous. It is only when another item B is shown against the same red background that the representation of the red background becomes more contextual. The participant now knows what dimension is particularly relevant and it becomes even more so with additional items added into this associative structure. Thus, with additional item-context pairings, the contextual representation evolves to accommodate additional complexity. It is worth noting that the evolution of the contextual representation is a slow and iterative process (particularly with respect to events or items within that context). Thus, we reiterate that returning to that stable state is not in conflict with Tenet 1. Context can slowly change over time, but still be a stable state that can be reactivated.

Tenet 3: Context is behaviorally relevant

Finally, we posit that it is important for a contextual representation to guide future behavior based on previous experiences. From an evolutionary perspective, context is critical for living in social groups and for basic survival techniques, such as food caching. Discriminating one food cache from another, combining the what, where, and when of the event, has been demonstrated in birds [31,95]. Further, these birds have shown the flexible use of contexts to optimize their performance [96]. Even when task demands do not explicitly place a premium on remembering contexts, there may be an adaptive value to remembering all of the associations and honing in on the relevant associations over time. For example, contexts can be transformed into schemas that allow for rapid processing to facilitate memory for schema-consistent information [97]. These schemas develop over multiple exposures to individual episodes, with the relevant associations reinforced through trial and error [98,99]. The underlying schemas can then be used to guide future behavior when encoding and retrieval contexts overlap [100], which is exemplified by state-dependent memory paradigms. These paradigms refer to superior memory performance when information is retrieved in the same mood [101], physical state [102], or location [103] as it was initially encountered. These situational contingencies also create a contextual background associated with the learning that occurs in them. Note that our proposed conceptual treatment of contexts as rich, complex, Hebbian associational structures is mechanistically consistent with state-dependent learning. We suggest that these paradigms are a quintessential demonstration of the utility and behavioral relevance of contextual information.

An important way to conceptualize behavioral relevance is in terms of implicit or explicit task demands. Returning to the bird caching example, sometimes context is required to discriminate between one specific episode and another. Determining which features are critical for the recall and reinstatement of the memory during retrieval is critical for contextually-based memory. Specifically, when the context is diagnostic, it offers discriminatory power to separate the target episode from other similar episodes. Smith and Mizumori [55] suggested that context arises from “a particular situation or set of circumstances that must be differentiated from other situations in order for subjects to retrieve the correct behavioral or mnemonic output”. As such, context has also been operationally defined by the task demands, such as reward contingencies [55] or problem-solving strategy [104], rather than by environmental stimuli. For example, Smith and Mizumori [55] showed context-specific responses in the hippocampus when rats were required to discriminate between contexts, but not when they were randomly foraging in those same environments. While this is a strong definition of the behaviorally-relevant aspect, we feel that there is a critical element being highlighted. Relatedly, one can consider the potential issue of the MRI scanner itself becoming contextual in a human fMRI experiment. This tenet mitigates that concern to an extent: though the scanner environment is certainly stable and inexorably linked to the situation the participant finds herself or himself in, it typically has no relevance to completing the task at hand. Critically, in a given experiment, behavioral relevance makes the influence of context, however it is being operationalized, testable.

Application of the Three Tenets

Consider two examples of how context has been operationalized in the field: contextual fear conditioning in rodents and object-scene pairings in humans. Both reasonably satisfy these three tenets. In contextual fear conditioning, the conditioned chamber a rat encounters is stable, as is the fact that the aversive event occurs in that stable environment. The neural representation for this environment can be observed each time that the rat encounters the chamber (Tenet 1). We note here that our use of “stable” does not preclude contextual associations from being formed in only a few or even one learning event. An event that is only encoded once can certainly feature contextual information, provided that the information is informative (e.g., being shocked in a new environment). Secondly, context in this paradigm is complex, involving multiple dimensions in the environment (e.g., color, texture, pattern), as well as emotional and motivational state (Tenet 2), allowing researchers to more specifically test or isolate its role. Finally, freezing in one context but not another demonstrates the behavioral relevance of the context to the animal (Tenet 3).

Turning to the case of object-scene pairings or object-location pairings in human experiments, if certain objects are consistently paired with certain scenes, the relationship between object and scene is stable, and the scene may serve as a form of context for that object (Tenet 1). The complexity of the relationship, outside of a simple 1:1 association is more difficult to address (Tenet 2). On one hand, associating an object with a complex and multifaceted scene or a particular location among many possible locations does not appear to be simple. On the other hand, it is reasonable to suppose that these pairings between an object and a scene or location could be overly simplistic, and may actually be tapping into a very basic form of associative memory rather than “context” per se. This issue may similarly extend to contextual fear conditioning in rodents: though the rat or mouse has associated shock with a novel three-dimensional space, is it relating a complex representational structure to that shock, or is it simply a 1:1 mapping between the shock and the bad room? Recent studies in rodents [60,61] and humans [79] have begun to address these issues by increasing the complexity of associations in tasks, and while not perfect, they offer major steps toward ecological validity. Nonetheless, complexity and evolution of associational structure is certainly a component of contextual representations as we experience them.

The behavioral relevance of the context to the task can be relatively straight-forward in the object-scene or object-location tasks when participants perform a recognition task based on the conjunction of the context and object (Tenet 3). However, we advocate the selection of a specific learned response from among multiple other options [60,61] as a more powerful approach. Researchers often assign specific responses to test whether information is being accurately represented (e.g., “yes/no” recognition of consistent and inconsistent object-scene pairings, or source memory judgments), which can be particularly effective if a subject must select a response among more than two possibilities (e.g., a rat digging in cup A when it is to the left of cup B only in the black room, but not in the white room). This approach accomplishes two simple things: (1) it pushes a subject to encode multiple contextual elements (Tenet 2), and (2) the behavioral readout is more specific and correct behavior is less likely to be arrived at by chance, improving the ability to infer which contextual elements are being retrieved and represented (Tenet 3). In sum, although selecting a specific learned response from among multiple options may not be the most ecologically valid form of behavioral relevance in every experiment, it nonetheless can be used to successfully differentiate whether information is being accurately or inaccurately represented and used. In general, going beyond binary correct/incorrect decisions is a fruitful approach. Thus, object-scene pairings can be a decent approach to studying context memory, but only with careful attention to the study design and task parameters that emphasize the three tenets outlined here.

Returning to how we began our discussion, the purpose of memory is to let our past experiences guide our current and future behavior. As we have described, the representation of context evolves with experience and adapts to highlight relevant elements. This behavioral relevance can be in explicit learning paradigms or in implicit cases such as contextual fear conditioning, where again we note that time must be spent in the context prior to the shock before such contextual learning occurs enough to let the animal discriminate between the shocked chamber and any other. The representation of context is created and tuned in the potential service of adaptive behavior.

Conclusions

Context has been studied from a vast array of approaches that differ significantly in how it is being manipulated and defined. As we vary the way that we operationalize context across experiments, we risk losing this core definition of context, resulting in conflicting results and localization of function. For example, while we refer to context as a global state or some conjunction of conditions, we often operationalize it to a single variable. While such simplicity has its merits in science and often leads to a great deal of progress, we suggest that here it may often amount to throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater as, in so doing, we can turn the experiment into a test of associative memory between two elements rather than a test of how we represent context. Moving forward, a major unresolved question to be addressed by future studies is whether context is simply equal to the sum of its component associations, or whether it is in some way “special”. We proposed three tenets that allow us to examine context in an operationalized and consistent manner across studies, approaches, and species. They also offer mechanistic and testable ways by which to parametrically vary “how contextual” a context can be. In other words, while it is perhaps easier to propose that a context must satisfy all three criteria, we suggest that a more fruitful approach would be to characterize a putative context in terms of how much it is able to satisfy those criteria relevant to perhaps another context or relevant to the items in the context. A continuous rather than absolute approach allows us to examine context as a multidimensional space, and compare contexts against one another. This perhaps allows us to move closer to a universally agreeable way to define and study context.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01 AG034613; CS] and [R01 MH10239, R21 AG049220, P50 AG16573; MY], and the National Science Foundation [GRF DGE1232825; ZR].

References

- 1.Mandler G. Recognizing: The judgment of previous occurrence. Psychol Rev. 1980;87:252–271. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.87.3.252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JJ, Fanselow MS. Modality-specific retrograde amnesia of fear. Science. 1992;256:675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1585183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curzon P, Rustay NR, Browman KE. Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning for Rodents. In: Buccafusco JJ, editor. Methods Behav Anal Neurosci. 2. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton (FL): 2009. [accessed December 23, 2016]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK5223/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vazdarjanova A, McGaugh JL. Basolateral amygdala is not critical for cognitive memory of contextual fear conditioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15003–15007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez S, Liu X, Lin P-A, Suh J, Pignatelli M, Redondo RL, Ryan TJ, Tonegawa S. Creating a false memory in the hippocampus. Science. 2013;341:387–391. doi: 10.1126/science.1239073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert PE, Kesner RP. Role of the rodent hippocampus in paired-associate learning involving associations between a stimulus and a spatial location. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:63–71. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day M, Langston R, Morris RGM. Glutamate-receptor-mediated encoding and retrieval of paired-associate learning. Nature. 2003;424:205–209. doi: 10.1038/nature01769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajji T, Chapman D, Eichenbaum H, Greene R. The role of CA3 hippocampal NMDA receptors in paired associate learning. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2006;26:908–915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4194-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaffan D. Dissociated effects of perirhinal cortex ablation, fornix transection and amygdalectomy: evidence for multiple memory systems in the primate temporal lobe. Exp Brain Res. 1994;99:411–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00228977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malkova L, Mishkin M. One-trial memory for object-place associations after separate lesions of hippocampus and posterior parahippocampal region in the monkey. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2003;23:1956–1965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01956.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannula DE, Ranganath C. The eyes have it: hippocampal activity predicts expression of memory in eye movements. Neuron. 2009;63:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staresina BP, Duncan KD, Davachi L. Perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices differentially contribute to later recollection of object- and scene-related event details. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31:8739–8747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4978-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uncapher MR, Otten LJ, Rugg MD. Episodic encoding is more than the sum of its parts: an fMRI investigation of multifeatural contextual encoding. Neuron. 2006;52:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reagh ZM, Yassa MA. Object and spatial mnemonic interference differentially engage lateral and medial entorhinal cortex in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U A. 2014;111:E4264–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411250111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henson RN, Rugg MD, Shallice T, Josephs O, Dolan RJ. Recollection and familiarity in recognition memory: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1999;19:3962–3972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03962.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasselmo ME, Eichenbaum H. Hippocampal mechanisms for the context-dependent retrieval of episodes. Neural Netw Off J Int Neural Netw Soc. 2005;18:1172–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiers HJ, Maguire EA. A navigational guidance system in the human brain. Hippocampus. 2007;17:618–626. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown TI, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE. A high-resolution study of hippocampal and medial temporal lobe correlates of spatial context and prospective overlapping route memory. Hippocampus. 2014;24:819–839. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steemers B, Vicente-Grabovetsky A, Barry C, Smulders P, Schröder TN, Burgess N, Doeller CF. Hippocampal Attractor Dynamics Predict Memory-Based Decision Making. Curr Biol CB. 2016;26:1750–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman W. Memory for the time of past events. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:44–66. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eichenbaum H, Fortin N. Episodic memory and the hippocampus: It’s about time. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eacott MJ, Easton A. Episodic memory in animals: remembering which occasion. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:2273–2280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fortin NJ, Agster KL, Eichenbaum HB. Critical role of the hippocampus in memory for sequences of events. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:458–62. doi: 10.1038/nn834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naya Y, Suzuki WA. Integrating what and when across the primate medial temporal lobe. Science. 2011;333:773–776. doi: 10.1126/science.1206773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen TA, Morris AM, Mattfeld AT, Stark CE, Fortin NJ. A Sequence of events model of episodic memory shows parallels in rats and humans. Hippocampus. 2014;24:1178–88. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehn H, Steffenach H-A, van Strien NM, Veltman DJ, Witter MP, Håberg AK. A specific role of the human hippocampus in recall of temporal sequences. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2009;29:3475–3484. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5370-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh L-T, Gruber MJ, Jenkins LJ, Ranganath C. Hippocampal activity patterns carry information about objects in temporal context. Neuron. 2014;81:1165–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard MW, Kahana MJ. A distributed representation of temporal context. J Math Psychol. 2002;46:269–299. doi: 10.1006/jmps.2001.1388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrell S. Temporal clustering and sequencing in short-term memory and episodic memory. Psychol Rev. 2012;119:223–271. doi: 10.1037/a0027371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polyn SM, Norman KA, Kahana MJ. A context maintenance and retrieval model of organizational processes in free recall. Psychol Rev. 2009;116:129–156. doi: 10.1037/a0014420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayton NS, Dickinson A. Episodic-like memory during cache recovery by scrub jays. Nature. 1998;395:272–4. doi: 10.1038/26216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ergorul C, Eichenbaum H. The hippocampus and memory for “what,” “where,” and “when”. Learn Mem Cold Spring Harb N. 2004;11:397–405. doi: 10.1101/lm.73304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffman ML, Beran MJ, Washburn DA. Memory for “what”, “where”, and “when” information in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2009;35:143–152. doi: 10.1037/a0013295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland SM, Smulders TV. Do humans use episodic memory to solve a What-Where-When memory task? Anim Cogn. 2011;14:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s10071-010-0346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKenzie S, Frank AJ, Kinsky NR, Porter B, Rivière PD, Eichenbaum H. Hippocampal representation of related and opposing memories develop within distinct, hierarchically organized neural schemas. Neuron. 2014;83:202–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keene CS, Bladon J, McKenzie S, Liu CD, O’Keefe J, Eichenbaum H. Complementary Functional Organization of Neuronal Activity Patterns in the Perirhinal, Lateral Entorhinal, and Medial Entorhinal Cortices. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2016;36:3660–3675. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4368-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staresina BP, Davachi L. Differential encoding mechanisms for subsequent associative recognition and free recall. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2006;26:9162–9172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2877-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Medial temporal lobe activity during source retrieval reflects information type, not memory strength. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22:1808–1818. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balch L, WRBS Music-dependent memory: the roles of tempo change and mood mediation. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1996;22:1354–63. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isarida T, Sakai T, Kubota T, Koga M, Katayama Y, Isarida TK. Odor-context effects in free recall after a short retention interval: a new methodology for controlling adaptation. Mem Cognit. 2014;42:421–433. doi: 10.3758/s13421-013-0370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isarida T, Isarida TK. Effects of simple- and complex-place contexts in the multiple-context paradigm. Q J Exp Psychol 2006. 2010;63:2399–2412. doi: 10.1080/17470211003736756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moscovitch M, Nadel L, Winocur G, Gilboa A, Rosenbaum RS. The cognitive neuroscience of remote episodic, semantic and spatial memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bousfield WA. The occurrence of clustering in the recall of randomly arranged associates. J Gen Psychol. 1953;49:229–240. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1953.9710088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cofer CN, Bruce DR, Reicher GM. Clustering in free recall as a function of certain methodological variations. J Exp Psychol. 1966;71:858–866. doi: 10.1037/h0023217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yee E, Thompson-Schill SL. Putting concepts into context. Psychon Bull Rev. 2016;23:1015–1027. doi: 10.3758/s13423-015-0948-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirsh R. The hippocampus and contextual retrieval of information from memory: a theory. Behav Biol. 1974;12:421–444. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(74)92231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers CE, Gluck MA. Context, conditioning, and hippocampal rerepresentation in animal learning. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:835–847. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anagnostaras SG, Gale GD, Fanselow MS. Hippocampus and contextual fear conditioning: recent controversies and advances. Hippocampus. 2001;11:8–17. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2001)11:1<8::AID-HIPO1015>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gale GD, Anagnostaras SG, Fanselow MS. Cholinergic modulation of pavlovian fear conditioning: effects of intrahippocampal scopolamine infusion. Hippocampus. 2001;11:371–376. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanders MJ, Wiltgen BJ, Fanselow MS. The place of the hippocampus in fear conditioning. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map: Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 1971;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mizumori SJY. Context prediction analysis and episodic memory. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:132. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizumori SJY. Hippocampal place fields: relevance to learning and memory. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wikenheiser AM, Redish AD. Changes in reward contingency modulate the trial-to-trial variability of hippocampal place cells. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:589–598. doi: 10.1152/jn.00091.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith DM, Mizumori SJY. Learning-related development of context-specific neuronal responses to places and events: the hippocampal role in context processing. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2006;26:3154–3163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3234-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muller RU, Kubie JL. The effects of changes in the environment on the spatial firing of hippocampal complex-spike cells. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1951–1968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Treves A, Rolls ET. Computational analysis of the role of the hippocampus in memory. Hippocampus. 1994;4:374–391. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marr D. Simple memory: A theory for archicortex. Philos Trans R Soc LondonSeries B Biol Sci. 1971;262:23–81. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Treves A, Rolls ET. Computational constraints suggest the need for two distinct input systems to the hippocampal CA3 network. Hippocampus. 1992;2:189–99. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buzsaki G. Rhythms of the Brain. Oxford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buzsáki G, Moser EI. Memory, navigation and theta rhythm in the hippocampal-entorhinal system. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:130–138. doi: 10.1038/nn.3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Imaging recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe: a three-component model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mickes L, Seale-Carlisle TM, Wixted JT. Rethinking Familiarity: Remember/Know Judgments in Free Recall. J Mem Lang. 2013;68:333–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yonelinas AP, Otten LJ, Shaw KN, Rugg MD. Separating the brain regions involved in recollection and familiarity in recognition memory. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2005;25:3002–3008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5295-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takashima A, van der Ven F, Kroes MCW, Fernández G. Retrieved emotional context influences hippocampal involvement during recognition of neutral memories. NeuroImage. 2016;143:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maratos EJ, Rugg MD. Electrophysiological correlates of the retrieval of emotional and non-emotional context. J Cogn Neurosci. 2001;13:877–891. doi: 10.1162/089892901753165809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith APR, Henson RNA, Dolan RJ, Rugg MD. fMRI correlates of the episodic retrieval of emotional contexts. NeuroImage. 2004;22:868–878. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Penick S, Solomon PR. Hippocampus, context, and conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1991;105:611–617. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kitamura T, Sun C, Martin J, Kitch LJ, Schnitzer MJ, Tonegawa S. Entorhinal Cortical Ocean Cells Encode Specific Contexts and Drive Context-Specific Fear Memory. Neuron. 2015;87:1317–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakazawa Y, Pevzner A, Tanaka KZ, Wiltgen BJ. Memory retrieval along the proximodistal axis of CA1. Hippocampus. 2016;26:1140–1148. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knierim JJ, Neunuebel JP, Deshmukh SS. Functional correlates of the lateral and medial entorhinal cortex: objects, path integration and local-global reference frames. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369:20130369. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Witter MP, Wouterlood FG, Naber PA, Van Haeften T. Anatomical organization of the parahippocampal-hippocampal network. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;911:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burwell RD, Bucci DJ, Sanborn MR, Jutras MJ. Perirhinal and postrhinal contributions to remote memory for context. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2004;24:11023–11028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3781-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bucci DJ, Saddoris MP, Burwell RD. Contextual fear discrimination is impaired by damage to the postrhinal or perirhinal cortex. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:479–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bucci DJ, Robinson S. Toward a conceptualization of retrohippocampal contributions to learning and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2014;116:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Place R, Farovik A, Brockmann M, Eichenbaum H. Bidirectional prefrontal-hippocampal interactions support context-guided memory. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:992–994. doi: 10.1038/nn.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kveraga K, Ghuman AS, Kassam KS, Aminoff EA, Hämäläinen MS, Chaumon M, Bar M. Early onset of neural synchronization in the contextual associations network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3389–3394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013760108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aminoff EM, Kveraga K, Bar M. The role of the parahippocampal cortex in cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huffman DJ, Stark CEL. The influence of low-level stimulus features on the representation of contexts, items, and their mnemonic associations. NeuroImage. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Muckli L, Petro LS. The Significance of Memory in Sensory Cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:255–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weinberger NM. Specific long-term memory traces in primary auditory cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:279–290. doi: 10.1038/nrn1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosenthal CR, Andrews SK, Antoniades CA, Kennard C, Soto D. Learning and Recognition of a Non-conscious Sequence of Events in Human Primary Visual Cortex. Curr Biol CB. 2016;26:834–841. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cooke SF, Komorowski RW, Kaplan ES, Gavornik JP, Bear MF. Visual recognition memory, manifested as long-term habituation, requires synaptic plasticity in V1. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:262–271. doi: 10.1038/nn.3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ji D, Wilson MA. Coordinated memory replay in the visual cortex and hippocampus during sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nn1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haggerty DC, Ji D. Activities of visual cortical and hippocampal neurons co-fluctuate in freely moving rats during spatial behavior. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:11–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aly M, Turk-Browne NB. Attention promotes episodic encoding by stabilizing hippocampal representations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E420–429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518931113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aly M, Turk-Browne NB. Attention Stabilizes Representations in the Human Hippocampus. Cereb Cortex N Y N 1991. 2016;26:783–796. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wheeler ME, Petersen SE, Buckner RL. Memory’s echo: Vivid remembering reactivates sensory-specific cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11125–11129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ezzyat Y, Davachi L. Similarity breeds proximity: pattern similarity within and across contexts is related to later mnemonic judgments of temporal proximity. Neuron. 2014;81:1179–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kragel JE, Morton NW, Polyn SM. Neural activity in the medial temporal lobe reveals the fidelity of mental time travel. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2015;35:2914–2926. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3378-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Holland PC. Occasion Setting in Pavlovian Conditioning. In: Medin DL, editor. Psychol Learn Motiv. Academic Press; 1992. pp. 69–125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Holland PC, Bouton ME. Hippocampus and context in classical conditioning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Robertson B-A, Eacott MJ, Easton A. Putting memory in context: dissociating memories by distinguishing the nature of context. Behav Brain Res. 2015;285:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Feeney MC, Roberts WA, Sherry DF. Memory for what, where, and when in the black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) Anim Cogn. 2009;12:767–777. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.LaDage LD, Roth TC, Fox RA, Pravosudov VV. Flexible cue use in food-caching birds. Anim Cogn. 2009;12:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ghosh VE, Gilboa A. What is a memory schema? A historical perspective on current neuroscience literature. Neuropsychologia. 2014;53:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bartlett FC. Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rumelhart DE, Ortony A. Sch Acquis Knowl. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1976. The representation of knowledge in memory; pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Smith SM, Vela E. Environmental context-dependent memory: a review and meta-analysis. Psychon Bull Rev. 2001;8:203–220. doi: 10.3758/bf03196157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Erk S, Kiefer M, Grothe J, Wunderlich AP, Spitzer M, Walter H. Emotional context modulates subsequent memory effect. NeuroImage. 2003;18:439–447. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peters R, McGee R. Cigarette smoking and state-dependent memory. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;76:232–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00432551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Godden DR, Baddeley AD. Context-Dependent Memory in Two Natural Environments: On Land and Underwater. Br J Psychol. 1975;66:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975.tb01468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yeshenko O, Guazzelli A, Mizumori SJY. Context-dependent reorganization of spatial and movement representations by simultaneously recorded hippocampal and striatal neurons during performance of allocentric and egocentric tasks. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:751–769. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]