Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in the management of premenstrual syndrome.

Design

Systematic review of published randomised, placebo controlled trials.

Studies reviewed

10 trials of progesterone therapy (531 women) and four trials of progestogen therapy (378 women).

Main outcome measures

Proportion of women whose symptoms showed improvement with progesterone preparations (suppositories and oral micronised). Proportion of women whose symptoms showed improvement with progestogens. Secondary analysis of efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in managing physical and behavioural symptoms.

Results

Overall standardised mean difference for all trials that assessed efficacy of progesterone (by both routes of administration) was −0.028 (95% confidence interval −0.017 to −0.040). The odds ratio was 1.05 (1.03 to 1.08) in favour of progesterone, indicating no clinically important difference between progesterone and placebo. For progestogens the overall standardised mean was −0.036 (−0.014 to −0.060), which corresponds to an odds ratio of 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11) showing a statistically, but not clinically, significant improvement for women taking progestogens.

Conclusion

The evidence from these meta-analyses does not support the use of progesterone or progestogens in the management of premenstrual syndrome.

What is already known on this topic

The premenstrual syndrome affects about 1.5 million women in the United Kingdom

There are numerous treatment options, progesterone being one of the most strongly advocated

Progesterone and progestogens are among the most widely prescribed treatments for premenstrual syndrome in the United Kingdom and the United States

What this study adds

There is no evidence to support the claimed efficacy of progesterone in the management of premenstrual syndrome

There is insufficient evidence to make a definitive statement about progestogens, but current evidence suggests that they are not likely to be effective

Introduction

Premenstrual syndrome is defined as the recurrence of psychological and physical symptoms in the luteal phase, which remit in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. It is estimated that up to 1.5 million women in the United Kingdom experience such severe symptoms that their quality of life and interpersonal relationships are greatly affected. Over 35% of these women will seek medical treatment.1

The rationale for the use of progesterone and progestogens in the management of premenstrual syndrome is based on the unsubstantiated premise that progesterone deficiency is the cause.2 Although initial data suggest there to be abnormal concentrations of metabolites of progesterone (pregnanolone and allopregnanolone),3 there is no consistent evidence that low concentrations of progesterone are found in women with the premenstrual syndrome. Indeed, published studies have shown progesterone to be the same in women with and without premenstrual syndrome.4 However, as premenstrual syndrome occurs in ovulatory cycles progesterone may be the underlying cause or at least the trigger for symptoms in susceptible women. Women taking hormone replacement therapy experience typical symptoms seen in premenstrual syndrome (progestogen induced premenstrual syndrome).5

In 1989 the National Association of Premenstrual Syndrome sent a questionnaire to general practitioners and found that over half prescribed progesterone pessaries or suppositories and over 60% prescribed progestogens6 for women with premenstrual syndrome. In the United States and Canada an earlier study found that 70% of prescriptions for premenstrual syndrome were for progesterone suppositories or pessaries.7 From 1993 to 1998 progestogens and progesterone remained the most widely prescribed treatments for premenstrual syndrome in the United Kingdom (unpublished data).

In the United Kingdom, the only licensed preparation of progesterone is Cyclogest, administered as a suppository or pessary. Oral micronised progesterone has been available for some time in Europe and the United States but not in the United Kingdom. Crinone, a vaginal progesterone gel, does not have a UK pharmaceutical licence, but it is listed for treatment of premenstrual syndrome in the Monthly Index of Medical Specialties (MIMS). Topical, “natural” progesterone cream has, without evidence, been extensively marketed through the internet and lay media as a reputedly effective treatment for premenstrual syndrome.8

Progestogens are also prescribed for premenstrual syndrome on the basis of their “progesterone-like” action. Dydrogesterone, norethisterone, and levonogestrel have pharmaceutical licences in the United Kingdom, despite the apparent paradox of claimed effectiveness of treatment versus their ability to generate side effects similar to those seen in the premenstrual syndrome.5 This, together with the seeming lack of evidence from clinical trials for the efficacy of progesterone or progestogens, the known failure of transdermal preparations of progesterone to achieve measurable increase in blood concentrations of progesterone,9,10 and the continued popularity in prescribing these treatments for premenstrual syndrome led us to undertake a detailed review of clinical trials of all types of progestogens and progesterone therapy in the management of premenstrual syndrome.

Methods

Trials

We searched medical databases for reports of published clinical trials of progesterone and progestogens in the management of premenstrual syndrome. MeSH terms used were premenstrual syndrome, progesterone, and progestogen, as well as the individual drug names, together with title and abstract searches for keywords progesterone, progestogen, premenstrual syndrome, premenstrual tension (PMT), late luteal phase dysphoric disorder (LLPDD), premenstrual dysphoria (PMD), and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). We searched Embase (1988-2000), Medline (1966-2000), PsychINFO (1988-2000), and the Cochrane controlled trial register. References cited in all trials were searched iteratively to identify missing studies. All languages were included. Pharmaceutical companies who manufacture progesterone preparations (oral micronised, intramuscular, vaginal gel, topical cream, or suppositories) and progestogens were contacted. We included trials that investigated the effect of progesterone or progestogens on premenstrual symptoms if they were randomised, placebo controlled, double blind studies that included patients with a pretreatment diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome, for which all data from the trials could be acquired.

Data extraction and outcome measures

All the data were extracted independently in duplicate by two investigators (PWD, KMW) by means of a standardised protocol and data collection form. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third investigator (SO'B). When there were insufficient data presented for inclusion, we contacted authors for further details. We collected data on the dosage and preparation of treatment. The main outcome measure was a reduction in overall symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. Combined or overall symptoms was chosen in an attempt to overcome the clinical heterogeneity associated with the measurement and scoring of symptoms used in individual trials. When possible we quoted results using intention to treat, as such results represent an accurate means of determining the efficacy of a drug. We undertook separate analyses of micronised oral progesterone and progesterone pessaries or suppositories versus placebo. We carried out a secondary analysis of the treatment of behavioural and physical symptoms. Withdrawals from treatment and side effects were recorded.

Quality assessment

We assessed trial quality using a scale developed by Jadad et al,11 which assesses the randomisation, double blinding, reports of drop outs, and withdrawals for the trials, and our own quality scale, which assesses the quality of the trials for study design, reproducibility, and statistical analysis. This eight point scale comprised the following: confirmation that no other medications or oral contraceptives were being taken; a power calculation to justify patient numbers or more than 65 participants in each arm (enabling detection of a small effect size of 0.3, see below); a single, clearly stated dose of drug; reproducible measurement of premenstrual symptoms; clear presentation of results; a description of the number and reason for trial withdrawals; exclusion of, or a separate analysis of, participants with a major psychiatric disorder; and whether or not the trial was supported by independent funding. We awarded one point for each category present in the trial. Each trial was independently scored by two investigators and the third investigator arbitrated on any disagreements. We used predetermined criteria for the recognition of the highest quality trials. A score of 3 or more was required in the Jadad score for the trial to be designated “high quality” and included in the meta-analysis11; a score of less than 3 meant that the trial was designated “low quality.” We have given results for our quality score, but we did not use it as a criterion for inclusion because the score has not been validated.

Statistical analysis

When continuous data were presented we calculated a standardised mean difference. This is equivalent to an effect size, which is a dimensionless quantity representing the difference between two means as a number of SDs. The magnitude of an effect size has been described by Cohen12; 0.3 represents a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 1.0 a large effect. A negative effect size means a reduction in symptoms. When medians and ranges were presented the values were converted to means (SD).13 When comparisons were made between pooled standardised mean differences for different subanalyses, we assessed statistical differences using a z test; P<0.05 was considered significant. We calculated an overall standardised mean difference using both fixed and random effects models. The overall standardised mean difference was converted to an odds ratio with the association described by Hassleblad and Hedges.14 Homogeneity was tested for with a χ2 test, with P<0.05 indicating significant heterogeneity.

We used the method of Egger et al15 to detect bias (such as publication and location bias) in the included trials with a funnel plot. We assessed the asymmetry of the funnel plot quantitatively by plotting a linear regression of the standard normal deviate (standardised mean difference divided by SE) against precision (inverse of SE). A regression line that passes through the origin of the plot (within error limits) indicates symmetry and hence the absence of bias.

Results

We identified 14 published trials that assessed the efficacy of progesterone in the management of premenstrual syndrome.16–29 We excluded four: two because of their low quality score on the Jadad scale,26,27 one because the data could not be extracted,29 and one because the trial failed to make a prospective diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome before randomisation.24 Ten trials remained, representing 531 women with data suitable for inclusion in the analyses. One trial compared both progesterone suppositories and oral micronised progesterone with placebo, and the data were analysed as two studies.16

We identified 15 published trials that assessed progestogen in the management of premenstrual syndrome.30–44 We excluded 12: three were open studies,41–43 four did not include a prospective diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome,34,36–38 three were preliminary reports of included trials,35,40,44 and in two data could not be extracted.33,39 Of the three remaining trials one compared two different progestogens (each with their own placebo) and so this trial was treated as two separate studies.30

Table 1 gives details of the included trials for both treatments, and table 2 lists the excluded trials and their reason for exclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis of treatment of premenstrual syndrome

| Study | Participants | Intervention | Outcome measures | Reported results | Withdrawals/side effects | Source of funding | Quality score (Jadad/ own) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | ||||||||

| Van der Meer et al, 198325 | 20 completed crossover | 2x200 mg/day rectal suppositories for 4 months | 4 point scale for: depression, irritability, fatigue, concentration, anxiety, aggression, headache, breast pain, abdominal pain, nausea, obstipation, oedema | No more effective than placebo | 7 drop outs, no reported side effects | Not stated | 3/7 | |

| Dennerstein et al, 198523 | 23 completed crossover | 3x100 mg/day oral micronised progesterone for 4 months | Moos MDQ, BDI, SSAI, daily symptom record | Appreciable benefit over placebo | 1 drop out, none due to side effects | Not stated | 4/6 | |

| Andersch and Hahn, 198522 | 20 randomised 15 completed crossover | 2x100 mg/day vaginal suppositories for 2 months | CPRS scale | No difference over placebo | 5 drop outs, no reported side effects | Not stated | 3/6 | |

| Maddocks et al, 198621 | 48 randomised 20 completed | 2x200 mg/day luteal phase suppositories for 6 months | Moos MDQ, BDI, SSAI, PMS self rating scale | Not significantly different from placebo | 28 drop outs, 2 due to side effects, 1 placebo, 1 progesterone | Not stated | 3/7 | |

| Rapkin et al, 198728 | 8 randomised 8 completed crossover | 200 mg/day luteal phase suppositories for 6 months | Daily diary scores for psychological, behavioural, and somatic symptoms, POMS | Not significantly different from placebo | No drop outs, no reported side effects | Not stated | 5/6 | |

| Corney et al, 199020 | 47 randomised 19 completed | 2x200 mg/day continuous suppositories for 6 months | PMS self rating scale, GHQ, social problem questionnaire | Not significantly different from placebo | 28 drop outs due to side effects (individual numbers not presented) | Independent | 3/6 | Trial compared progesterone, placebo and behavioural therapy. Neither treatment better than placebo |

| Freeman et al, 199019 | 187 randomised 121 completed crossover | 400 mg/day cycle 1, 800 mg/d cycle 2 luteal phase suppositories | DSR, clinical global rating, HAM-D, Hopkins symptom checklist, PAF | Not significantly different from placebo | 8 drop outs due to side effects (individual numbers not given) | Independent (pharmaceutical company provided progesterone) | 4/8 | |

| Magill, 199518 | 141 randomised 93 completed | 2x400 mg/day luteal phase suppositories for 4 months | 150 symptom checklist | Not significantly different from placebo when results analysed as intention to treat | 4 drop outs due to side effects (2 in each arm) | Trial funded by pharmaceutical company | 4/7 | |

| Freeman et al, 199517 | 106 randomised 93 completed | 4x300 mg/day luteal phase up to 12x300 mg/d flexible dosing oral micronised | Daily symptom report, clinical and patient global rating, symptom severity | Oral micronised progesterone no better than placebo | Individual drop out numbers not presented: reasons and numbers for drop outs did not differ between treatment arms | Independent (pharmaceutical company provided progesterone) | 3/7 | Alprazolam was another treatment arm. Alprazolam was significantly better than progesterone and placebo |

| Vanselow et al, 199616 | 39 randomised 25 completed crossover | 3x100 mg/day luteal phase oral progesterone 2x100 mg/day luteal phase progesterone pessary 3x2 months | Menstrual distress questionnaire, BDI, state anxiety and anger scales | No difference between either active treatment and placebo | 4 drop outs due to side effects (1 placebo; 3 progesterone pessary; 0 oral progesterone) | Funded by Laboritoires Besins-Iscovesco, France | 4/7 | |

| Progestogen | ||||||||

| West, 199030 (medroxy- progesterone) | 19 completed crossover | 3x5 mg/day medroxyprogesterone 21 days of each cycle for 3 cycles | VAS for 7 symptoms | Significant improvement in psychological and breast symptoms | 8 drop outs, 3 due to side effects | Independent | 3/6 | Breakthrough bleeding occurred in 74% of the cycles treated with medroxyprogesterone |

| West, 199030 (norethisterone) | 16 completed crossover | 3x5 mg/day norethisterone for 21 days of cycle for 3 cycles | VAS for 7 symptoms | Significant improvement for breast symptoms only | 5 drop outs, 3 due to side effects | Independent | 3/6 | |

| Dennerstein, 198632 | 24 completed crossover | 2x10 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 12-26 of cycle for 4 cycles | MDQ, mood adjective checklist, DSR, BDI, SSAI | No more effective than placebo | 6 drop outs, 3 due to side effects | Independent | 3/7 | |

| Williams, 198331 | 260 completed parallel | 2x10 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 12 to menses for 3 cycles | Daily symptom diary | No significant difference | 40 drop outs due to side effects | 4/6 | ||

Moos MDQ=Moos menstrual distress questionnaire; BDI=Beck depression inventory; CPRS=clinical psychiatric rating scale; POMS=profile of mood states; GHQ=general health questionnaire; DSR=daily symptom record; SSAI=Spielberger state anxiety inventory; VAS=visual analogue scale; HAM-D=Hamilton rating scale for depression; PAF=premenstrual assessment form.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies excluded from meta-analysis of treatment of premenstrual syndrome

| Study | Participants | Intervention progesterone | Reason for exclusion | Reported results | Side effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richter et al, 198424 | 40 women referred from general practice | 400 mg/day progesterone suppository luteal phase | No prediagnosis of PMS; women recruited with self diagnosis | More women believed that progesterone gave symptom relief than placebo | No withdrawals due to side effects | No difference in improvement seen between treatment groups |

| Smith et al, 197529 | 14 randomised | 50 mg intramuscular progesterone every other day in luteal phase | Insufficient published results for data analysis | 3 women felt better on progesterone, 3 women felt better during progesterone free months; 8 women found no difference | No withdrawal, side effects not mentioned | Trial was a crossover of 4 treatment regimens: progesterone; progesterone plus spironolactone; spironolactone; placebo injections and tablets |

| Sampson, 197927 | 32 randomised, 24 completed crossover | 2x200 mg/day, 2x400 mg/day suppositories luteal phase for 2 months | Low Jadad score | No significant difference from placebo | 400 mg: 7 drop outs; 800 mg: 9 drop outs; none due to side effects | |

| Baker et al, 199526 | 17 completed multiple crossover | 2x200 mg/day vaginal suppositories luteal phase for 7 months | Low Jadad score | No overall difference from placebo; significant improvement for tension, mood swings irritability, control | None reported | Trial assessed only psychological symptoms |

| Coppen, 196933 | 17 completed parallel trial | 2x7.5 mg/day norethisterone on day 16-25 of cycle | Data presented not suitable for extraction | Not effective in improving premenstrual symptoms | None reported | Norethisterone was also compared with diuretic, Dytide |

| Hoffmann, 198834 | 161 completed parallel trial | 2x10 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 12-menses for 3 cycles | No prospective diagnosis of PMS | No clinically relevant effect | 38 drop outs, 3 due to side effects | |

| Haspels, 198035 | 123 completed parallel trial | 2x10 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 12-menses for 4 cycles | Subgroup of patients from included study[15] | Significantly better than placebo for psychological symptoms and clinically better for somatic symptoms | 27 drop outs, none due to side effects | British arm of European study |

| Jordheim, 197236 | 35 completed parallel trial | 3x2.5 mg medroxyprogesterone 10 days before menstruation | No placebo arm, no prospective diagnosis of PMS | No significant effect | None stated | Medroxyprogesterone compared with medroxyprogesterone plus diuretic |

| Kerr, 198037 | 67 completed | 2x10 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 12-menses for 4 cycles | No preliminary diagnosis; single blind trial | Unclear: “dydrogesterone is a useful agent” | 36 drop outs, 3 due to side effects | Trial funded by pharmaceutical company |

| Hellberg, 199138 | 38 completed crossover | 5 mg/day medroxyprogesterone acetate for 3 cycles | No prospective diagnosis of PMS | Significantly better than placebo | 5 drop outs, none due to side effects | 2 interventions compared with placebo; spironolactone (50mg/day) also better than placebo |

| Sampson, 198839 | 69 completed crossover | 2x10 mg/day dydrogesterone for 14 days of cycle for 4 cycles | Data presented not suitable for extraction | Significant decrease in pain with menstrual bleeding and breast symptoms only | 39 drop outs, 5 due to side effects | |

| Sampson, 198240 | Same patient group as above | |||||

| Taylor, 197742 | 50 completed | 2x10 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 12-26 of cycle for 2 or more cycles | Open trial; no prospective diagnosis | Measureable improvement in 70% of patients | None | |

| Strecker, 198143 | 31 completed | 20 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 15-25 of cycle | Open trial; no prospective diagnosis | Beneficial for relief of some symptoms | No side effects reported | |

| Strecker, 198044 | Same patient group as above | |||||

| Morse, 199141 | 14 completed | 20 mg/day dydrogesterone on day 17-27 for 3 cycles | Open trial | Some short term symptom relief | No drop outs due to side effects | Dydrogesterone v cognitive therapy and relaxation therapy |

Quality assessment of trials

All the included trials of progesterone and progestogens scored ⩾3 on the Jadad scale. On our quality score four of the 10 progesterone trials20,22,23,28 and two of the three progestogen trials30,31 scored 6, five progesterone trials16–18,21,25 and the other progestogen trial32 scored 7, and one trial of progesterone scored the maximum of 8.9

Data extraction

All the included trials for either treatment presented continuous data and so an overall standardised mean difference was calculated with both fixed and random effects models. Because we found only minimal differences between the fixed and random effects models we used the more conservative random effects model.

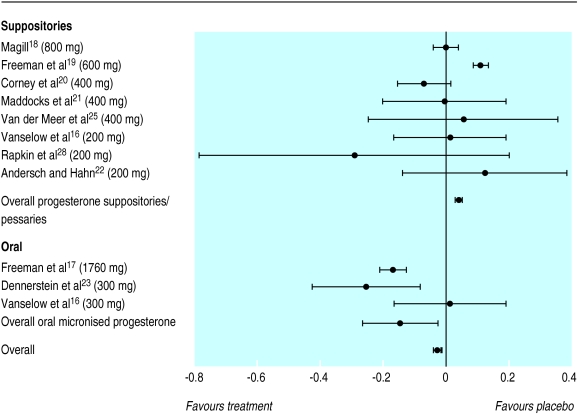

Progesterone

The overall standardised mean difference for a reduction in premenstrual syndrome symptoms with progesterone suppositories or pessaries was 0.04 (95% confidence interval 0.03 to 0.05) and hence was marginally in favour of placebo. This difference corresponds to an odds ratio of 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95). The figures for oral micronised progesterone were −0.15 (−0.17 to −0.12), marginally in favour of oral micronised progesterone, corresponding to an odds ratio of 1.30 (1.25 to 1.36), showing a slight improvement for women taking oral micronised progesterone. When we combined all the trials of progesterone (by both routes of administration) the overall result showed no clinically significant difference between progesterone and placebo, although the result was statistically significant (−0.028, −0.017 to −0.0408; corresponding odds ratio 1.05,1.03 to 1.08) in favour of progesterone. The pooled trials were statistically homogeneous (P=0.999). Figure 1 shows the individual standardised mean difference for each trial, the type of preparation and dosage for that trial, and the pooled standardised mean difference with 95% confidence intervals for trials that used progesterone suppositories and those that used oral micronised progesterone. The inclusion of the data from the two low quality trials25,26 did not significantly affect the overall result.

Figure 1.

Standardised mean differences and 95% confidence intervals for proportion of patients who showed improvement in overall premenstrual syndrome (progesterone versus placebo). Negative values indicate reduction in symptoms, favouring active treatment

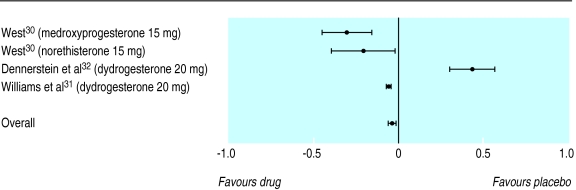

Progestogens

The overall standardised mean difference for reduction in symptoms showed a slight difference between progestogens and placebo in favour of progestogens (−0.036, –0.059 to −0.014), the corresponding odds ratio being 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11). The pooled trials were statistically homogeneous (P=0.999). Figure 2 shows the individual standardised mean difference for each trial, the type of progestogen used in the trial, and the pooled standardised mean difference with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Standardised mean differences and 95% confidence intervals for proportion of patients who showed improvement in overall premenstrual syndrome (progestogen versus placebo). Negative values indicate reduction in symptoms, favouring active treatment

Bias

We investigated bias using a funnel plot.15 Regression analysis of the plots indicated no significant asymmetry (intercept=2.97, −3.88 to 9.82, P=0.45, for progesterone and intercept=0.80, −9.79 to 11.4, P=0.85, for progestogens) and thus no evidence of bias.15

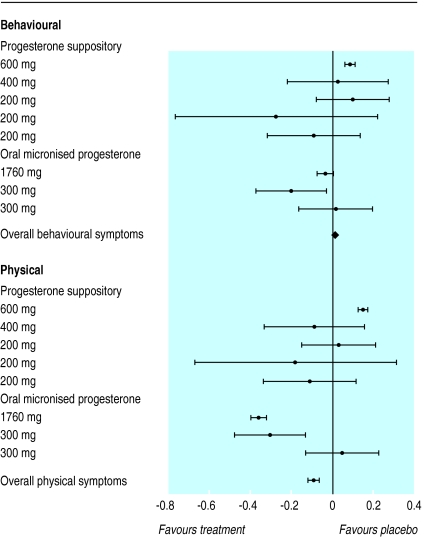

Subanalyses

We carried out a subanalysis of the effectiveness of the treatments in managing either physical or behavioural symptoms. Figure 3 shows the overall standardised mean difference for behavioural and physical symptoms from eight of the trials of progesterone, which represented 371 women. The overall standardised mean difference was 0.011 (−0.003 to 0.024) for behavioural symptoms and −0.088 (−0.061 to −0.115) for physical symptoms. There was no significant variation in the overall standardised mean differences (P=0.357). This was also true when the treatments were further divided into progesterone suppositories and oral micronised progesterone.

Figure 3.

Standardised mean differences and 95% confidence intervals for proportion of patients who showed improvement in behavioural and physical symptoms (progesterone versus placebo)

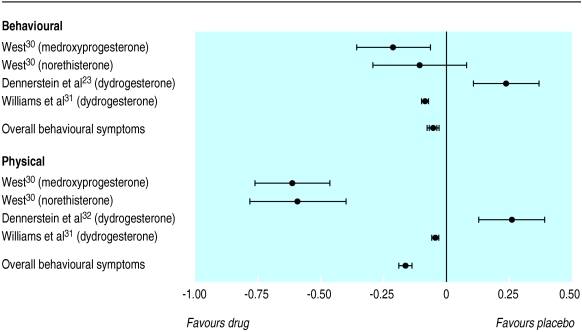

Figure 4 shows the individual standardised mean difference for the progestogen trials that reported behavioural and physical symptoms separately. The overall standardised mean difference was −0.06 (−0.04 to −0.07) for behavioural symptoms compared with −0.16 (−0.13 to −0.19) for physical symptoms. Progestogens seem to be more effective in alleviating physical symptoms than behavioural symptoms (P<0.0001), although the magnitude of the effect size for physical symptoms is not considered to be clinically significant.

Figure 4.

Standardised mean differences and 95% confidence intervals for proportion of patients who showed improvement in behavioural and physical symptoms (progestogen versus placebo)

Side effects

We extracted data on side effects (when reported) from the included trials (table 3). The data in the trials were incomplete; five of the trials did not give a detailed breakdown of side effects or the number of participants who suffered from them. The most commonly reported side effect for progesterone administered as a suppository or pessary was an increase or decrease in the length of the menstrual cycle; the most commonly reported side effect for oral micronised progesterone was fatigue or sedation. We analysed withdrawals from progesterone trials due to side effects, comparing placebo with treatment. This showed an increased but not significant risk of drop out due to side effects in the treatment group (odds ratio 1.66, 0.43 to 6.79).

Table 3.

Side effects reported in included studies of progesterone according to method of administration

| Side effect | Suppository/pessary

|

Oral micronised

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Placebo | Drug | Placebo | ||

| Cycle length changes | 40 | 42 | 5 | 5 | |

| Breast swelling/bloating | 28 | 20 | 5 | 8 | |

| Change in blood loss | 24 | 28 | |||

| Nausea | 19 | 14 | 2 | 1 | |

| Vaginal pruritus | 19 | 13 | |||

| Cramps | 13 | 15 | 4 | 2 | |

| Headache | 12 | 5 | 9 | 0 | |

| Flu-like symptoms | 7 | 3 | |||

| Pregnancy | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Dysmenorrhoea | 5 | 5 | |||

| Depression | 3 | 8 | 3 | 0 | |

| Dizziness/lightheadedness | 3 | 4 | 24 | 6 | |

| Rectal pain | 3 | 3 | |||

| Anxiety | 2 | 5 | |||

| Acne | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| Fatigue/sedation | 2 | 2 | 46 | 23 | |

| Insomnia | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Hot flushes | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| Confusion/memory problems | 1 | 3 | 17 | 1 | |

| Body hair growth | 1 | 2 | |||

| Decreased libido | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Night terrors | 1 | 1 | |||

| Increased appetite | 1 | 1 | |||

| Altered taste | 1 | 1 | |||

| Dry skin | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ringing in ears | 1 | 0 | |||

| Totals | 194 | 180 | 126 | 60 | |

None of the included trials gave a detailed breakdown of side effects for progestogens. We noted withdrawals from trials due to side effects, comparing placebo with progestogens. This showed a non-significant higher dropout rate in the treatment group due to side effects (1.65, 0.86 to 3.21).

Discussion

The meta-analyses that we carried out in this systematic review show that there is no published evidence to support the use of either progesterone or progestogens in the management of the premenstrual syndrome.

The premenstrual syndrome has been considered to be an endocrine disorder. This is based on the observation that symptoms are reduced or eliminated during pregnancy (when progesterone concentrations are high and non-cyclical) and are absent during non-ovulatory cycles and after the menopause.44 As early as 1938 it was proposed that premenstrual syndrome was caused by relative, unopposed oestrogen during the luteal phase.45 Dalton and Green developed this theory further in the 1950s, and Dalton still remains one of the main proponents of the progesterone deficiency theory. No research, however, has convincingly shown a progesterone deficiency in women with premenstrual syndrome.46

Many therapeutic interventions have been claimed to be effective. This may be attributed to a high placebo effect and the large number of poorly controlled trials in women without a pretrial diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome. It is because of the known high placebo response associated with premenstrual syndrome that one of the stated inclusion criteria for our meta-analyses was that in all trials the women should have had premenstrual syndrome diagnosed before randomisation. We also considered only randomised, double blind placebo controlled trials suitable for analysis. It could be argued that women with self diagnosed premenstrual syndrome would, in fact, be the population that the clinician treats. However, in a meta-analysis it is essential that the trials have defined the disorder precisely before treatment to permit definitive statements on the efficacy of the given treatment to be made.

Progesterone

Of the ten trials of progesterone treatment that met the inclusion criteria, eight assessed progesterone suppositories and three used oral micronised progesterone (one trial compared both suppositories and oral micronised preparations and the two arms were treated as two separate trials). There are no published trials of topical progesterone cream, which has been popularised through the media and the internet.8One trial of intramuscular progesterone was identified, but the data were presented in a textbook review chapter in a format that was not extractable.29 This placebo controlled trial involved only 14 women with premenstrual syndrome and concluded that progesterone did not produce a significant beneficial effect. Of the eight adequately controlled trials of progesterone suppositories, all but one showed a negative result. The only study that claimed to show a positive result was the study by Magill.18 However, when we examined the data on an intention to treat basis, as opposed to an analysis of “completers,” we could not show a beneficial effect.

We found a small positive effect of progesterone over placebo in the three trials that assessed oral micronised progesterone. This may be due to the ability of this treatment to increase concentrations of allopregnanolone and pregnanolone (metabolites of progesterone), which have a positive effect on the central nervous system similar to that of GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid). Progesterone administered as a suppository or pessary does not increase concentrations of these metabolites.16,47

The positive result for oral micronised progesterone was due mainly to one trial conducted by Freeman et al in 1995, which involved 170 women.17 Although it seems significantly positive in this meta-analysis, the conclusion by the authors of that trial was that “oral micronised progesterone therapy was no better than placebo.” This standardised mean difference (−0.147) should be compared with the overall standardised mean difference from another meta-analysis of treatment for premenstrual syndrome, which used the same inclusion criteria.48 The overall standardised mean difference for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was −1.066 in favour of treatment. These standardised mean differences correspond to an odds ratio of 1.3 for oral micronised progesterone and 6.91 for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.49 It should also be noted that oral micronised progesterone is not available in the United Kingdom.

The overall result showed that progesterone was slightly better than placebo for treating physical symptoms but was no better than placebo in managing behavioural symptoms, although this difference was not significant. This is true for both progesterone suppositories and oral micronised progesterone.

The published evidence for progestogen treatment is not of high quality. Of the 15 published trials, only four trials met quality criteria. They represented 378 women in total, of whom 159 received the active treatment. We carried out a sensitivity analysis on the three trials (266 women) that were excluded because of lack of a prospective diagnosis. The inclusion of the low quality trials slightly improved the effect size (overall standardised mean difference −0.182, −0.044 to 0.320) but not to the extent of making it clinically significant. Poorly controlled, low quality trials often have positive results. In the case of premenstrual syndrome this is often due to an imprecise definition of the study population and a subsequent uncertainty as to what condition is being treated.

Of the four included studies, two used dydrogesterone, one used norethisterone, and one used medroxyprogesterone. The lack of trials and the low numbers of participants in each trial meant that a comparative analysis of individual progestogens could not be undertaken. Progestogens were slightly more effective at treating physical compared with behavioural symptoms, but again there was no clinically significant improvement.

While the role of endogenous progesterone and its metabolites in the aetiology of premenstrual syndrome remains unclear, it is evident from this meta-analysis that exogenous administration of either progestogens or progesterone does not improve symptoms. This is not surprising as there are reliable data to refute the theory that premenstrual syndrome is caused by a progesterone deficiency. With this review, there is now no convincing evidence to support the continued prescription of progesterone or progestogens for the management of premenstrual syndrome.

Footnotes

Funding: No external funding.

Competing interests: SO'B has been reimbursed for lectures and conferences by Hoechst Marion Roussel, Shire Pharmaceuticals, SmithKline Beecham, Eli Lilly, Searle, Sanofi Winthrop, Zeneca, Galen Laboratories, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, and Novo Nordisk. He has also received funds for research staff from Searle, SmithKline Beecham, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi Winthrop. He is married to a member of the research department of Zeneca Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Hylan TR, Sundell K, Judge R. The impact of premenstrual symptomatology on functioning and treatment-seeking behavior: experience from the United States, United Kingdom, and France. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:1043–1052. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalton K. The premenstrual syndrome and progesterone therapy. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: Year Book Medical Publisher; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, Brann DW, Simone D, Mahesh VB. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:709–714. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redei E, Freeman EW. Daily plasma estradiol and progesterone levels over the menstrual cycle and their relation to premenstrual symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)00057-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammarback S, Backstrom T, Holst J, von Schoultz B, Lyrenas S. Cyclical mood changes as in the premenstrual tension syndrome during sequential estrogen-progestogen postmenopausal replacement therapy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1985;64:393–397. doi: 10.3109/00016348509155154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart A. A rational approach to treating the premenstrual syndrome. Seal, Kent: National Association of Premenstrual Syndrome; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon KE, Lyon MA. The premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:705–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JR. Natural progesterone. The multiple roles of a remarkable hormone. Sebastopol, CA: BLL Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper A, Spencer C, Whitehead MI, Ross D, Barnard GJR, Collins WP. Systemic absorption of progesterone from Progest cream in menopausal women. Lancet. 1998;351:905–906. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey BJ, Carey AH, Patel S, Carter G, Studd JWW. A study to evaluate serum and urinary hormone levels following short and long term administration of two regimens of progesterone cream in postmenopausal women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;107:722–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadad A, Moore M, Carrol D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised clinical trials; is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatfield C. Statistics for technology. London: Chapman Hall; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasselblad V, Hedges LV. Meta-analysis of screening and diagnostic tests. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:167–178. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanselow W, Dennerstein L, Greenwood KM, de Lignieres B. Effect of progesterone and its 5 alpha and 5 beta metabolites on symptoms of premenstrual syndrome according to route of administration. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;17:29–38. doi: 10.3109/01674829609025661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M. A double-blind trial of oral progesterone, alprazolam, and placebo in treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome. JAMA. 1995;274:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magill PJ. Investigation of the efficacy of progesterone pessaries in the relief of symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. Progesterone study group. Br J Gen Pract. 1995;45:589–593. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman E, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M. Ineffectiveness of progesterone suppository treatment for premenstrual syndrome. JAMA. 1990;264:349–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corney RH, Stanton R, Newell R. Comparison of progesterone, placebo and behavioural psychotherapy in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;11:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maddocks S, Hahn P, Moller F, Reid RL. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of progesterone vaginal suppositories in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:573–581. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90604-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersch B, Hahn L. Progesterone treatment of premenstrual tension—a double blind study. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:489–493. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennerstein L, Spencer-Gardner C, Gotts G, Brown JB, Smith MA, Burrows GD. Progesterone and the premenstrual syndrome: a double blind crossover trial. BMJ. 1985;290:1617–1621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6482.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter MA, Haltvick R, Shapiro SS. Progesterone treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Curr Ther Res. 1984;36:850. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Meer YG, Benedek-Jaszmann LJ, Van Loenen AC. Effect of high-dose progesterone on the pre-menstrual syndrome; a double blind crossover trial. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;2:220–222. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker ER, Best RG, Manfredi RL, Demers LM, Wolf GC. Efficacy of progesterone vaginal suppositories in alleviation of nervous symptoms in patients with premenstrual syndrome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1995;12:205–209. doi: 10.1007/BF02211800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampson GA. Premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind controlled trial of progesterone and placebo. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;135:209–215. doi: 10.1192/bjp.135.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rapkin AJ, Chang LH, Reading AE. Premenstrual syndrome; a double blind placebo controlled study of treatment with progesterone vaginal suppositories. J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;7:217–220. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith SL. Mood and the menstrual cycle. In: Sachar EJ, editor. Topics in psychoendocrinology. New York: Grine and Stratton; 1975. pp. 19–58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.West CP. Inhibition of ovulation with oral progestins—effectiveness in premenstrual syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;34:119–128. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(90)90015-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams JGC, Martin AJ, Hulkenberg-Tromp A. Premenstrual syndrome in four European countries. Part 2. A double blind controlled study of dydrogesterone. Br J Sexual Med. 1983;10:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dennerstein L, Morse C, Gotts G, Brown J, Smith M, Oats J. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome. A double-blind trial of dydrogesterone. J Affect Disord. 1986;11:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coppen AJ, Milne HB, Outram DH, Weber JCP. Dytide, norethisterone and placebo in the premenstrual syndrome. Clinical Trials J. 1969;6:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann V, Pedersen PA, Philip J, Fly P, Pedersen C. The effect of dydrogesterone on premenstrual symptoms. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1988;6:179–183. doi: 10.3109/02813438809009313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haspels AA. A double blind, placebo controlled multi-centre study of the efficacy of dydrogesterone (Duphaston) In: Van Keep PA, Utian WH, editors. The premenstrual syndrome. Lancaster: MTP Press; 1980. pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jordheim O. The premenstrual syndrome. Clinical trials of treatment with a progestogen combined with a diuretic compared with both a progestogen alone and with a placebo. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1972;51:77–80. doi: 10.3109/00016347209154971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr GD, Day JB, Munday MR, Brush MG, Watson M, Taylor RW. Dydrogesterone in the treatment of the premenstrual syndrome. Practitioner. 1980;224:852–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hellberg D, Claesson B, Nilsson S. Premenstrual tension: a placebo-controlled efficacy study with spironolactone and medroxyprogesterone acetate. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1991;34:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(91)90357-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampson GA, Heathcote PR, Wordsworth J, Prescott P, Hodgson A. Premenstrual syndrome. A double-blind cross-over study of treatment with dydrogesterone and placebo. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:232–235. doi: 10.1192/bjp.153.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sampson GA, Heathcote PR, Wordsworth J, Prescott P. Preliminary report: a double-blind crossover study to assess the benefits of dydrogesterone and placebo in premenstrual syndrome. In: Taylor RW, editor. Proceedings of workshop on premenstraul syndrome. London: Medical News Group; 1982. pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morse C, Dennerstein L, Farrell E, Varnavides K. A comparison of hormone therapy, coping skills training and relaxation for the relief of premenstrual syndrome. J Behav Med. 1991;14:469–489. doi: 10.1007/BF00845105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor RW. The treatment of premenstrual tension with dydrogesterone (Duphaston) Curr Med Res Opin. 1977;4:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strecker JR. An explorative study into the clinical effects of dydrogesterone in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. In: Van Keep PA, Utian WH, editors. The premenstrual syndrome. Lancaster: MTP Press; 1981. pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strecker JR. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with retroprogesterone (Duphaston) Fortschr Med. 1980;98:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Backstrom T, Sanders D, Leask R, Davidson D, Warner P, Bancroft J. Mood, sexuality, hormones and the menstrual cycle. II. Hormone levels and their relationship to the premenstrual syndrome. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1983;45:503–507. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Israel SL. Premenstrual tension. JAMA. 1938;110:1721. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maxson WS. The use of progesterone in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1987;30:465–477. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198706000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeLignieres B, Dennerstien L, Backstrom T. Influence of route of administration on progesterone metabolism. Maturitas. 1995;21:251–271. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(94)00882-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dimmock PW, Wyatt KM, Jones PW, O'Brien PMS. Efficacy of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]