Abstract

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) face a range of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) challenges. Clinical, behavioural and structural interventions have each reduced these risks and improved health outcomes. However, combinations of these interventions have not been compared with each other or with no intervention at all. The ‘Girl Power’ study is designed to systematically make these comparisons.

Methods and analysis

Four comparable health facilities in Malawi and South Africa (n=8) were selected and assigned to one of the following models of care: (1) Standard of care: AGYW can receive family planning, HIV testing and counselling (HTC), and sexually transmitted infection (STI) syndromic management in three separate locations with three separate queues with the general population. No youth-friendly spaces, clinical modifications or trainings are offered, (2) Youth-Friendly Health Services (YFHS): AGYW are meant to receive integrated family planning, HTC and STI services in dedicated youth spaces with youth-friendly modifications and providers trained in YFHS, (3) YFHS+behavioural intervention (BI): In addition to YFHS, AGYW can attend 12 monthly theory-driven, facilitator-led, interactive sessions on health, finance and relationships, (4) YFHS+BI+conditional cash transfer (CCT): in addition to YFHS and BI, AGYW receive up to 12 CCTs conditional on monthly BI session attendance.

At each clinic, 250 AGYW 15–24 years old (n=2000 total) will be consented, enrolled and followed for 1 year. Each participant will complete a behavioural survey at enrolment, 6 months and 12 months . All clinical, behavioural and CCT services will be captured. Outcomes of interest include uptake of each package element and reduction in HIV risk behaviours. A qualitative substudy will be conducted.

Ethics/dissemination

This study has received ethical approval from the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board, the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee and Malawi’s National Health Sciences Research Committee. Study plans, processes and findings will be disseminated to stakeholders, in peer-reviewed journals and at conferences.

Keywords: epidemiology, international health services, public health, child protection

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Within each country, the selection of four comparable clinics and random assignment of each to one of the four models of service delivery is a key strength.

The potential for differential recruitment, retention and data ascertainment across sites are limitations.

The study is not powered to detect differences in biological outcomes, especially HIV incidence, a limitation.

Implementing a similar set of models in two distinct sub-Saharan contexts enhances generalisability, a key strength.

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) 15–24 years old are vulnerable to a wide range of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) challenges, including acquisition of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unintended and unwanted pregnancies, and intimate partner violence (IPV). These challenges have many common underlying health system, behavioural and structural drivers that have not, to our knowledge, been addressed and assessed in combination—in a youth-friendly service delivery environment, with behavioural interventions (BIs) and with socioeconomic support.

AGYW in SSA typically experience a service delivery environment characterised by judgemental provider attitudes, a lack of privacy, inconvenient hours and non-integrated services.1 As a result, service usage by AGYW for SRH remains low. Youth-friendly health services (YFHS) that include provider training, clinic modifications and community-based demand creation are promising approaches for increasing uptake of such services.1–6 Eight out of nine randomised or quasi-experimental studies in SSA assessing YHFS models with these components increased service uptake by AGYW.3 However, to our knowledge, such a platform has never been tested in combination with behavioural and structural interventions.

Offering BIs within a YFHS platform could further enhance service uptake and address other behavioural risks and psychosocial outcomes. The social context of intimate relationships in SSA is characterised by severe gender inequality. Gender norms favour male control over sexual intercourse, often leaving young women with less power in sexual decision-making.7–10 Additionally, many young women have older male partners, frequently with a transactional dimension, who are more likely to be HIV-infected.11–15 BIs based on the theory of gender and power,16 17 and social cognitive theory18 have been shown to address these power imbalances and reduce multiple partnerships, herpes simplex virus-2 incidence and IPV.19–21 All of these evidence-based interventions address gender norms and involve participatory activities for groups of young women. Synthesising the most effective elements of these ‘empowerment’ interventions and offering them within a YFHS service delivery platform could help reduce behavioural sources of risk, improve psychosocial outcomes and generate demand for health services. Assessing evidence-based clinical and BIs is a critical next step.

Cash transfers are also a promising tool for preventing HIV among AGYW.22–24 In Malawi, when cash payments were given to girls and their guardians, they were more likely to remain in school, less likely to report age–disparate relationships and have lower HIV and HSV-2 prevalence.22 In South Africa, adolescents living in homes receiving a national child grant reported half the incidence of transactional sex and much less age-disparate sex than those in homes not receiving it.23 In a South African trial, cash transfers conditioned on schooling did not lead to lowered HIV incidence but did lead to reductions in IPV and sexual risk.25 However, to our knowledge, a cash transfer programme has not been evaluated for AGYW in a clinical environment nor has it been implemented in combination with a BI. Understanding whether a cash transfer provides benefits in combination with a YFHS service delivery platform and empowerment-based BI is not known.

It is becoming widely acknowledged that combination HIV prevention packages that include effective, acceptable,and scalable clinical, sociobehavioural and structural interventions may have the greatest impact.26–29 However, it is not known how best to combine different intervention levels for maximal effectiveness for multiple outcomes. The Girl Power study is designed to compare three different combinations of evidence-based interventions with one another and with a standard of care (SOC) and to assess their impact on a range of care-seeking and sexual risk behaviours in two SSA countries.

Methods and analysis

Study setting

The Girl Power study is an ongoing study (February 2016–November 2017) being conducted in Malawi and South Africa. These countries represent two prototypical, yet distinct SSA contexts. In Malawi, based on nationally representative household data, first births often occur early, at a median age of 19 years and within the context of marriage.30 In South Africa, sexual activity tends to be outside of the context of marriage, with a somewhat later age of first birth.31 32 Malawi is characterised by extreme poverty with the majority of the population living on less than $1 per day, whereas South Africa has extreme wealth disparities. In spite of these socioeconomic differences, both countries have high HIV prevalence levels—6% of women 20–24 years old are HIV-infected in Malawi and 17% in South Africa, rates considerably higher than their male counterparts.30 Sexual violence is also a serious problem in both countries, with high rates of non-consensual sex reported by young women.33–35 Additionally, both have public sector health facilities with human resource shortages, stock-outs of pharmaceuticals and supplies, long queues and providers who exhibit negative attitudes towards AGYW. It was within these contexts that the Girl Power study was conceptualised.

Four comparable public sector health facilities were selected in each country. In Malawi, the four sites are public sector health centres in Lilongwe. All sites are on a main road, have antenatal volumes >200 clients per month and have antenatal HIV prevalence >5%. These sites have higher HIV prevalence than the surrounding rural areas where antenatal HIV prevalence is <5%. In South Africa, the four sites are in the Klipfontein and Mitchell’s Plain areas in the Western Cape, which serve primarily black and coloured populations. These are high-density, low socioeconomic periurban townships comprised predominantly of informal dwellings. Antenatal prevalence in the Western Cape is 17%. In both countries, each clinic serves distinct communities. In South Africa, biometric identification is being used to ensure the same people do not enrol in more than one site. In Malawi, all sites are at least 7 km apart.

Prior to the study, all sites in both countries offered free HIV testing and counselling (HTC), contraception and STI services in separate locations within each clinic with separate queues. Condoms were also available for free at all sites—in the pharmacy at the Malawian sites and throughout the clinic at the South African sites. At all sites in both countries, AGYW could receive general health services with the general population. However, there were no distinct YFHS spaces, times or providers, no BIs and no opportunities for conditional cash transfers (CCTs) within the clinic.

Study design and interventions

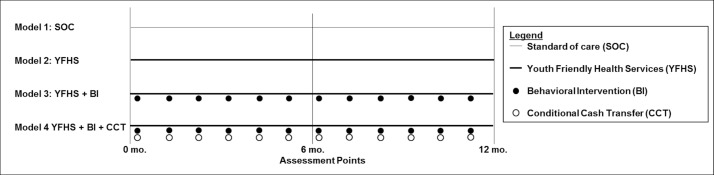

Girl Power is a quasi-experimental prospective cohort study comparing four different models of service delivery and their impacts on care-seeking and sexual risk behaviours among AGYW (figure 1). The primary outcomes of interest are service uptake and behavioural risks. Participants enrolled at all sites will complete behavioural surveys at baseline, 6 and 12 months and have their clinical data ascertained over a 1-year period. In each country, each clinic was randomly assigned to one of the following models of care:

Model 1: SOC: The SOC offers HTC, contraception, STI syndromic management and condoms to AGYW. However, healthcare providers have not been trained in YFHS and clinics have not made YFHS modifications, regarding hours, clinical navigation, integration, cost or space.

Model 2: YFHS: HTC, contraception and STI services are offered by health providers who have been trained in YFHS. YFHS modifications have been made to the clinics, including clinical navigation (both countries), a youth-only space with integrated service provision (Malawi) and longer hours (Malawi).

Model 3: YFHS+BI: In addition to the YFHS package, participants can attend 12 monthly facilitator-led, small-group interactive sessions. They are based on other evidence-based interventions from the region17 19 21 and are motivated by the theory of gender and power and social cognitive theory. These sessions address sexual health topics (eg, HIV, reproductive health), social issues (eg, partner communication, peer pressure and IPV), financial literacy (eg, budgeting, saving and investing) and general topics (eg, self-esteem, goal-setting and decision-making). Each session includes an activity to do at home after the session in order to encourage behavioural change. Each country adapted curricula in a culturally responsive manner; although sessions were not identical across countries, they explore similar themes. We expect sessions will be delivered to groups of 10–20 girls at once.

Model 4: YFHS+BI+CCT: In addition to the YFHS package and empowerment sessions, AGYW received a monthly CCT (approximately $6) conditional on attending the monthly empowerment session. Each young woman could receive up to 12 CCTs (1 per month). In Malawi, the CCT is being provided in physical cash and in South Africa the CCT is provided electronically.

Figure 1.

Depicts the study design. BI, behavioural intervention; CCT, conditional cash transfer; SOC, standard of care; YFHS, Youth-Friendly Health Services.

Study and clinical personnel, training activities and clinical modifications by country and model are described in greater detail in table 1.

Table 1.

Girl Power personnel, training and clinical modifications by clinic and country

| Malawi | South Africa | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Clinical model | SOC | YFHS | YFHS+BI | YFHS+BI+CCT | SOC | YFHS | YFHS+BI | YFHS+BI+CCT |

| Personnel | ||||||||

| Research | Research assistant: Young (<29) female full-time staff responsible for all consenting, screening, enrolment and behavioural surveys (1/clinic) | Research assistant: Female full-time staff responsible for all consenting, screening, enrolment and behavioural surveys (1/clinic) | ||||||

| Outreach | Peer outreach workers: Young full-time lay staff responsible for recruitment and retention activities (2/clinic) | Peer outreach workers/navigators: Young full-time lay staff responsible for recruitment and retention activities (outreach roles). They also welcome participants, assess their SRH needs and help with clinical navigation (2/clinic) | Peer outreach workers: Temporary staff responsible for community outreach and recruitment at study initiation (2/clinic) | |||||

| Navigation | – | Peer navigator: Full-time staff who welcome participants, discuss SRH needs, fetch patient files and help with clinical navigation (1/clinic) | ||||||

| Family planning and STI services | – | Nurses: 4–5 government nurses from these sites were assigned to rotate through a youth-focused Girl Power clinic | – | Nurses: 1–3 government nurses provide SRH services to Girl Power participants | ||||

| HIV counselling and testing | – | Counsellor: 1 young female HIV counsellor was assigned to the Girl Power clinic | – | Counsellor: 1–3 government HTC counsellors are available to attend to Girl Power participants | ||||

| Workshop facilitation | – | – | Facilitators: Young women lead empowerment sessions (1/facility) | – | – | Facilitators: Women lead empowerment sessions (1/facility) | ||

| Training | ||||||||

| Protocol training | – | Study overview and design, clinical data collection, good clinical practice (3 days) (all staff) | Study overview and design, data collection, SRH refresher, values clarification (1–2 days) | |||||

| YFHS training | – | Medical and psychosocial support for adolescents (2 day) (all staff) | – | Medical and psychosocial support for adolescents (1 day) (all staff) | ||||

| Clinical training | – | Nurses trained on long-acting reversible contraception (5 days) and STI syndromic management (5 days) | All nurses expected to be familiar with these provision of all contraceptive methods and STI syndromic management. Provided on-the-job training | |||||

| Clinical modifications | ||||||||

| Space | – | Dedicated space for AGYW service delivery in a separate area from general clinic to ensure privacy from adults | – | Dedicated waiting and/or welcome area for AGYW | ||||

| Hours | Typically morning hours | AGYW can come in the morning or afternoon | AGYW can come in the morning or afternoon | |||||

| Cost | STI medications require payment | All services are free | All services are free | |||||

AGYW, adolescent girls and young women; BI, behavioural intervention; CCT, conditional cash transfer; HTC, HIV testing and counselling; SOC, standard of care; SRH, sexual and reproductive health; STI, sexually transmitted infection;YFHS, Youth-Friendly Health Services.

Study population

At each of the eight sites, 250 AGYW will be recruited and followed for 1 year. Eligibility criteria include being female, 15–24 years old, residing in the clinic’s catchment area and willing to be enrolled for a 1-year period. The intention is to recruit AGYW who are already sexually active or likely to become sexually active, although this is not a strict eligibility criterion. In total, 1000 AGYW will be enrolled in each country (n=2000 total).

Recruitment will occur comparably at each site through a combination of community outreach activities, self-referral and referral through invitations from other participants. Outreach workers will visit parts of the catchment area known to be high risk. Through one-on-one conversations, they will build rapport, assess sexual activity and past care-seeking behaviours, promote the services at their site and invite them to participate. AGYW who enrol in the study will be provided with invitations to invite friends who they believe would also benefit.

Follow-up phone and physical tracing will be conducted for girls who miss their 6-month or 12-month visits. We will make comparable attempts to trace participants at all four clinics to avoid differential loss-to-follow-up and provide the same transport reimbursement for the three research visits across all four sites. These efforts are designed to minimise differential loss-to-follow-up.

Data collection and management

The two primary sources of data collection are a detailed behavioural survey and clinical service records. The behavioural survey is administered at three time points—at study enrolment, month 6 and month 12. The behavioural survey contains questions about demographics, socioeconomic status, past and current care-seeking behaviours, sexual history, depression (10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale), IPV (Modified Conflict Tactic Scale), alcohol consumption (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism brief alcohol screening tool). The 12-month assessment also includes assessments of the BI and the CCT. The behavioural survey will be self-administered in South Africa, except among illiterate participants; for these participants, it will be interviewer-administered. In Malawi, it will be interviewer-administered to all participants by young female research assistants. All surveys will be administered on encrypted password-protected Android tablets using Open Data Kit software and stored on secure servers.

In both countries, we will document delivery of HTC, family planning and STI services. Due to the unique clinical contexts, data collection will occur differently in the two countries. In Malawi, a clinic card that contains all clinical information has been developed for the study and will be used by clinical staff at each patient encounter and housed at the clinic. In South Africa, clinical staff will record clinical activities in existing clinical records and study staff will transcribe this information onto a study-specific form. In both countries, these data will then be entered into tablets in Open Data Kit by trained research assistants. In all clinics, study staff will systematically examine clinical records to ensure consistent ascertainment.

In both countries, each participant will be identified through a unique identifier. In South Africa, participants’ identities will be verified through biometric fingerprinting.

Study outcomes, analytical methods and sample size

The primary clinical outcomes are care-seeking behaviours using clinical data. Within each quarter, we will compare the proportion of participants who received HTC, male and/or female condoms, hormonal or long-acting contraception and both condoms and another form of contraception. We will also explore the proportion of participants who receive STI services. For all of these services, we will assess the proportion of participants who use each method ever, in each quarter and in all quarters. These data are available through clinical abstraction, the primary measure of clinical effectiveness. Details are reported in table 2.

Table 2.

Primary outcome measures

| Data source | Time period | Numerator | Denominator | |

| Primary clinical outcomes | ||||

| HIV testing uptake | Clinical record | Quarter 1, 2, 3,4, ever, all | Number with an HIV test recorded in each period | Persons HIV-negative or HIV-unknown in that period |

| Condom uptake | Clinical record | Quarter 1, 2, 3,4, ever, all | Number who received condoms in each period | Full cohort |

| Contraceptive uptake | Clinical record | Quarter 1, 2, 3,4, ever, all 4 | Number who received contraceptive pills or injections or received/continued long-acting contraception in each period | Full cohort |

| Dual method uptake | Clinical record | Quarter 1, 2, 3,4, ever, all | Number with condom and contraceptive uptake in each period | Full cohort |

| Primary sexual behaviour outcomes | ||||

| Age disparate sex | Behavioural survey | 12 months | Number reporting at least one current partner >10 years older | Number who took 12-month behavioural survey |

| Multiple partners in the last year | Behavioural survey | 12 months | Number reporting >1 sexual partner in the last year | Number who took 12-month behavioural survey |

| Physical IPV | Behavioural survey | 6 and 12 months | Number reporting physical IPV in that period | Number who took 6-month, 12-month behavioural surveys |

| Sexual IPV | Behavioural survey | 6 and 12 months | Number reporting physical IPV in that period | Number who took 6-month, 12-month behavioural surveys |

| Emotional IPV | Behavioural survey | 6 and 12 months | Number reporting physical IPV in that period | Number who took 6-month, 12-month behavioural surveys |

IPV, intimate partner violence.

HIV risk behaviours collected on the behavioural survey are primary behavioural outcomes of interest. Questions of particular interest are the proportion of AGYW who have multiple sexual partners, have a considerably older male partner and experience IPV. We will compare these indicators between participants in each country in each model.

For all primary clinical outcomes, we will conduct an intention to treat analysis, analysing each participant in her assigned clinic and assessing whether she received services in that clinic. We will use generalised estimating equations to account for correlated records between each participant at each time point. A log or identity link, binomial distribution and robust variance estimates will be used to estimate risk ratios and risk differences and 95% CIs. We will compare absolute differences at each time point, as well as changes over time.

In Stata V.12.0, we conducted two-sample tests of proportions to determine how much statistical power would be available to detect differences between any two arms at any time point within each country. Using an alpha level of 0.05 and a sample size of 250 participants per model, we have >80% power to detect differences >13% between any two models at any time point.

Qualitative substudy

A qualitative substudy will be conducted to better understand participant experiences with each service delivery model. Out of 15 in-depth interviews (IDIs), 12 will be conducted at each site in each country (n=96–120 IDIs total). IDIs will focus on individual experiences with SOC, YFHS, BI and CCT. At each clinic, we will purposively select a mixture of good care-seekers, poor care-seekers and HIV-infected young women. Focus group discussions (FGDs) (n=2–3/site) will address norms surrounding these same topics and strategies for improving or enhancing these services. At each site, we will have at least one FGD with adolescent girls 15–19 years old and one with young women 20–24 years old. IDIs and FGDs will be conducted in Chichewa in Malawi and in isiXhosa or English in South Africa. All IDIs and FGDs will be transcribed and translated into English. They will be coded and analysed using a thematic approach.

Ethics and dissemination

In South Africa, all AGYW 15–24 years could decide whether to provide informed consent for themselves; those 15–17 years could seek optional parental consent. We requested that minors 15–17 years be able to consent for themselves because they are able to receive all of these clinical services without parental consent. In a study designed to reduce barriers to care-seeking, obtaining parental consent could pose an undue barrier; the ethics committee agreed. In Malawi, AGYW 18–24 years will provide informed consent for themselves. AGYW 15–17 years will provide assent and have a parent, guardian or authorised representative provide informed consent. We requested that minors be able to consent as adults, but this provision was denied. At each site, a community club of individuals >18 years who could serve as authorised representatives will be established, a suggestion made by the National Health Sciences Research Committee (NHSRC).

Dissemination activities will occur at all stages of the study: prior to implementation, at intermediate points during implementation and at study culmination. Prior to study implementation, meetings were held with key local stakeholders, such as local health leadership (eg, district, province or city managers), clinical supervisors and clinical staff. These meetings were designed to seek permission for study implementation, orient these stakeholders to study goals and work together on implementation questions. Sensitisation activities were also conducted with key community stakeholders, such as local chiefs and religious leaders, school headmasters and library managers. These sensitisations were designed to inform key local leaders about the study, elicit buy-in and support and facilitate recruitment. During study implementation, these same stakeholders will be engaged to report on study progress and discuss challenges. At the end of the study, results will be disseminated so that stakeholders and participants are aware of the study’s primary findings. Additionally, in both countries, we have oriented policy-makers and implementing partners to study goals and progress. Results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals and at national and international meetings and conferences. Dissemination of final results is expected in 2018.

Discussion

Our findings will need to be interpreted in light of potential biases. First, each model may preferentially recruit persons who are interested in the services at that clinic. For example, the absence of services in model 1 may lead to recruitment of persons who do not need any services and the presence of a cash transfer in model 4 may lead to recruitment of persons in need of cash. We will explore whether baseline behavioural and socioeconomic characteristics differ by model, and if so, conduct adjusted analyses as needed. Second, it is possible that retention will be differential across arms. Different retention is precisely what we are trying to measure in clinical outcomes, but is problematic with respect to behavioural survey outcomes. To mitigate this risk, identical research incentives will be offered in all models at the three behavioural survey visits. We will explore the magnitude and nature of loss by clinic and use multiple imputation techniques and sensitivity analyses to address the loss that does occur. Differential ascertainment of clinical outcomes is a third potential source of bias: clinical staff trained in models 2, 3 and 4 may capture services more consistently than staff in clinic 1: apparent differences in service uptake could in fact be differences in data capture. Observing whether clinical records are consistent with self-report will allow us to explore this potential bias. Finally, enrolment in more than one model is possible in the Malawi sites, which do not have biometric identification. If such contaminations were to occur at a large scale, behavioural survey results would biased towards the null, as response options from the same participant at multiple clinics would be similar. In spite of these potential limitations, we believe Girl Power makes an important and unique contribution.

Conclusion

Implementing combination interventions for HIV prevention among AGYW in SSA has become a major focus of governments and donors over the last several years. In most cases, however, programmes have not been rigorously evaluated for impact. Girl Power is expected to address this important gap in understanding and provide greater insights into how to support vulnerable AGYW related to SRH and HIV in SSA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NER, AEP, L-GB, RM, JT, MCH, AK and LaM designed the study. TP, NM, NLB, DV, AM, BM and LuM were responsible for study coordination and data acquisition. All authors either wrote or made substantial edits to the draft, approved the final version and take responsibility for the work.

Funding: The Girl Power study is funded by Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa (EHPSA), a Department of International Development (DFID) programme managed by Mott MacDonald. NER is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R00MH104154).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (IRBIS 15–2901) and two local regulatory bodies: the Malawi NHSRC (15/7/1447) and the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee (815/2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Napierala Mavedzenge SM, Doyle AM, Ross DA. HIV prevention in young people in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:568–86. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mavedzenge SN, Luecke E, Ross DA. Effective approaches for programming to reduce adolescent vulnerability to HIV infection, HIV risk, and HIV-related morbidity and mortality: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66(Suppl 2):S154–S169. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denno DM, Hoopes AJ, Chandra-Mouli V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J Adolesc Health 2015;56(1 Suppl):S22–S41. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJ, et al. . Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reprod Health 2014;11:1 10.1186/1742-4755-11-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mbonye AK. Disease and health seeking patterns among adolescents in Uganda. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2003;15:105–12. 10.1515/IJAMH.2003.15.2.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross DA, Changalucha J, Obasi AI, et al. . Biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: a community-randomized trial. AIDS 2007;21:1943–55. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ed3cf5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacPhail C, Campbell C. ’I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things': condom use among adolescents and young people in a Southern African township. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:1613–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison A, Xaba N, Kunene P. Understanding safe sex: gender narratives of HIV and pregnancy prevention by rural South African school-going youth. Reprod Health Matters 2001;9:63–71. 10.1016/S0968-8080(01)90009-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettifor A, Macphail C, Anderson AD, et al. . ’If I buy the Kellogg’s then he should [buy] the milk': young women’s perspectives on relationship dynamics, gender power and HIV risk in Johannesburg, South Africa. Cult Health Sex 2012;14:477–90. 10.1080/13691058.2012.667575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaspan HB, Flisher AJ, Myer L, et al. . Sexual health, HIV risk, and retention in an adolescent HIV-prevention trial preparatory cohort. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:42–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. . Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet 2004;363:1415–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pettifor AE, Measham DM, Rees HV, et al. . Sexual power and HIV risk, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:1996–2004. 10.3201/eid1011.040252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert L, Raj A, Hien D, et al. . Targeting the SAVA (Substance Abuse, Violence, and AIDS) syndemic among women and girls: a global review of epidemiology and integrated interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69(Suppl 2):S118–27. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wamoyi J, Stobeanau K, Bobrova N, et al. . Transactional sex and risk for HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:20992 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. . Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1581–92. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav 2000;27:539–65. 10.1177/109019810002700502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingood GM, Reddy P, Lang DL, et al. . Efficacy of SISTA South Africa on sexual behavior and relationship control among isiXhosa women in South Africa: results of a randomized-controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63(Suppl 1):S59–65. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829202c4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 2001;52:1–26. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. . Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;337:a506 10.1136/bmj.a506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, et al. . Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet 2010;376:41–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. . A community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV/AIDS risk in Kampala, Uganda (the SASA! Study): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:96 10.1186/1745-6215-13-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, et al. . Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2012;379:1320–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes M, et al. . The child support grant and adolescent risk of HIV infection in South Africa--authors' reply. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e200 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70027-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Nguyen N, et al. . Can money prevent the spread of HIV? A review of cash payments for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav 2012;16:1729–38. 10.1007/s10461-012-0240-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Hughes JP, et al. . The effect of a conditional cash transfer on HIV incidence in young women in rural South Africa (HPTN 068): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e978–88. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30253-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Boyes ME, et al. . Cash plus care: social protection cumulatively mitigates HIV-risk behaviour among adolescents in South Africa. AIDS 2014;28(Suppl 3):S389–97. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vermund SH, Hayes RJ. Combination prevention: new hope for stopping the epidemic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2013;10:169–86. 10.1007/s11904-013-0155-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Yakubovich AR, et al. . Combination social protection for reducing HIV-risk behavior among adolescents in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72:96–104. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merson M, Padian N, Coates TJ, et al. . Combination HIV prevention. Lancet 2008;372:1805–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61752-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Statistics Office Malawi, ICF. 2017. Malawi demographic and health survey 2015-2016. Zomba, Malawi and Rockville, Maryland, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacPhail C, Pettifor AE, Pascoe S, et al. . Contraception use and pregnancy among 15-24 year old South African women: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. BMC Med 2007;5:31 10.1186/1741-7015-5-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistics South Africa. 2015. Census 2011: fertility in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. . Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence and revictimization among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:230–9. 10.1093/aje/kwh194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, et al. . Understanding men’s health and use of violence: interface of rape and HIV in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Medical Research Council, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.UNICEF. 2014. Violence against children and young women in Malawi: Findings from a national survey, 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.