Abstract

Pneumococcal macrolide resistance is usually expressed as one of two phenotypes: the M phenotype conferred by the mef gene or the MLSB phenotype caused by modification of ribosomal targets, most commonly mediated by an erm methylase. Target-site modification leading to antibiotic resistance can also occur due to sequence mutations within the 23S rRNA or the L4 and L22 riboproteins. We screened 4,535 invasive isolates resistant to erythromycin and 18 invasive isolates nonsusceptible to quinupristin–dalfopristin (Q-D) to deduce the potential mechanisms involved. Of 4,535 erythromycin-resistant isolates, 66.2% were polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive for mef alone, 17.8% for ermB alone, and 15.1% for both mef and ermB. Thirty-seven isolates (0.9%) were PCR negative for both determinants. Of these, 3 were positive for ermA (subclass ermTR) and 25 had chromosomal mutations. No chromosomal mutations (in 23S rRNA, rplD, or rplV) nor any of the macrolides/lincosamides/streptogramin (MLS) resistance genes screened for (ermT, ermA, cfr, lsaC, and vgaA) were found in the remaining nine isolates. Of 18 Q-D nonsusceptible isolates, 14 had chromosomal mutations and one carried both mef and ermB; no chromosomal mutations or other resistance genes were found in 3 isolates. Overall, we found 28 mutations, 13 of which have not been previously described in Streptococcus pneumoniae. The role of these mutations remains to be confirmed by transformation assays.

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, particularly in young children and elderly persons. The most important pneumococcal infections include pneumococcal pneumonia, meningitis, and bacteremia/septicemia, because of their high global disease burden, high case fatality rates, and associated costs.7 The introduction of the 7-valent vaccine in February of 2000 (PCV7, Prevnar; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals) had a major effect on the incidence of pneumococcal disease. By the end of 2001, the rate of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among US children younger than two years had decreased by 69%.8,53 Additionally, since five of the seven serotypes in PCV7 (6B, 9V, 14, 19F, and 23F) were responsible for most antibiotic-resistant infections in the United States, the overall rate of disease caused by penicillin-nonsusceptible pneumococcal strains decreased by 57% from 1999 to 2004.32 However, the proportion of erythromycin-resistant invasive isolates increased from 20.5% during 1999 to 24.9% during 2009.1

Pneumococcal macrolide resistance is usually expressed as one of two phenotypes: the M phenotype or the MLSB phenotype. M phenotype isolates are moderately resistant to 14- and 15-membered macrolides, due to the mef-encoded efflux mechanism, and susceptible to clindamycin.46 MLSB phenotype isolates are resistant to macrolides (with generally higher minimum inhibitory concentrations [MICs]), lincosamides (clindamycin), and streptogramin B, as a result of the modification of ribosomal targets, most commonly mediated by an erm methylase52; ermB is the predominant methylase found in S. pneumoniae, but ermA has also been reported.4,34,48 Both erm and mef genes are carried on mobile genetic elements.

While the ermB genotype is the most prevalent mechanism worldwide, occurring in 55% of all erythromycin-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates globally, the predominant mechanism of pneumococcal macrolide resistance in the United States was until recently mediated by the mefA gene. A study conducted in 1999, before the introduction of PCV7, found that the M phenotype accounted for 82% of erythromycin-resistant isolates. Most of these isolates were PCV7 types, which were most commonly associated with children younger than 5 years.26 After the introduction of PCV7, the proportion of mef in the United States steadily decreased, while the prevalence of macrolide-resistant strains carrying both ermB and mefA genes has increased.15,18,19,20,21,27,28

Macrolide resistance has also been frequently reported to occur due to substitutions in the 23S rRNA and in the L4 and L22 riboproteins.6,25,49,50,54,56 Efflux mechanisms encoded by other genes such as vga and lsa have also been associated with macrolides/lincosamides/streptogramin (MLS) resistance in other species, and the multidrug resistance gene cfr, encoding a 23S rRNA methyltransferase, was recently identified for the first time in streptococci.51

To determine the molecular mechanisms involved, we screened a large number of erythromycin and/or clindamycin-resistant isolates and all quinupristin–dalfopristin (Q-D) nonsusceptible isolates, submitted to the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) (part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s [CDC] Emerging Infections Program: http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/index.html), from participating sites pre- (1999) and post-PCV7 introduction (2002–2007). In this report, we describe previously unreported ribosomal changes associated with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides and related antibiotics.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Twenty-six thousand nine hundred seventy-four invasive S. pneumoniae isolates were submitted to ABCs from participating sites (www.cdc.gov/abcs/methodology/surv-pop.html) pre- (1999) and post- (2002–2007) introduction of PCV7. Isolates were serotyped by latex agglutination and the Quellung reaction. MICs to erythromycin, clindamycin, and Q-D were determined by the broth microdilution method. Antibiotic resistance was determined based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints: for erythromycin and clindamycin, isolates with MIC ≥ 1 μg/ ml were classified as resistant, and for Q-D, isolates with MIC ≥ 2 μg/ml were classified as nonsusceptible.9,11 Inducible clindamycin resistance was determined by the D-zone disk diffusion test10,11 and broth microdilution using an erythromycin–clindamycin (ERY-CLD) combination well. Four thousand five hundred thirty-five isolates (16.8%) were erythromycin resistant and available for testing. Eighteen additional Q-D-nonsusceptible isolates were identified through ABCs (submitted from 1996 to 2010) and included in the study. Q-D breakpoints were also determined using E-tests, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification and sequencing

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of ermT, ermA (subclass ermTR), ermB, mef, rplD (L4), rplV (L22), and the 23S rRNA genes (domain II and V) was carried out using previously described protocols.45,47,48,57 Screening for genes cfr, lsaC, and vgaA was also carried out, as previously described.31,39,41 PCR products were purified using ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Inc.) and cycle sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 chemistry (Life Technologies Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.2 Sequencing reactions were purified using a Sephadex-based method; briefly, sequencing reactions were transferred onto Sephadex G-50 columns prepacked into microtiter filter plates (Millipore) and then centrifuged at 750 g for 2 min onto clean 96-well plates. Purified reactions were analyzed on an ABI3130xl automated sequencer. The sequences obtained were compared to the TIGR4 (NC003028) genome, and then screened against all whole genome shotgun sequences available in the NCBI database.

Newly determined nucleotide sequence data have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KM098099-KM098108.

Results

Serotype and antimicrobial resistance

Forty-eight different serotypes were represented among the macrolide-resistant isolates included in this study. The five most common serotypes associated with macrolide resistance were 19A (26.2%), 14 (14.5%), 6A (9.1%), 15A (6.0%), and 6B (5.4%). During 1999, before the introduction of PCV7, the seven serotypes included in the vaccine accounted for 79.5% of macrolide-resistant invasive isolates; after PCV7 was introduced, this proportion decreased to 63.4% in 2002 ( p < 0.0001) and to 8.3% in 2007 (p < 0.0001). Among non-PCV7 serotypes, the largest changes in proportion among macrolide-resistant invasive isolates were observed in 19A (from 3.4% in 1999 to 42.3% in 2007, p < 0.0001) and 15A (from 0.3% to 12.5%, p < 0.0001), followed by 33F (from 0.3% to 7.3%, p < 0.0001) and 6C (from 0.7% to 5.9%, p < 0.0001).

Mechanisms of MLS resistance

The distribution of isolates positive for ermB and/or mef among PCV7 and non-PCV7 serotype isolates is shown in Table 1. The dual ermB + mef genotype increased significantly among these isolates from 1999 to 2007 ( p < 0.0001), while the mef-only genotype went from being found in 80% of the resistant invasive isolates in 1999 to accounting for only half of the resistant isolates in 2007. No significant changes were observed in the proportion of ermB-only genotype.

Table 1.

Distribution of ermB and mef Among Macrolide-Resistant Isolates Pre- and Post-PCV7 Introduction

| Year | ermB + (%) | ermB + /mef + (%) | mef + (%) | ermB− /mef− (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 120 (15.6) | 20 (2.6) | 615 (80.2) | 12 (1.6) | 767 |

| 2002 | 106 (20.6) | 29 (5.6) | 376 (73.0) | 4 (0.8) | 515 |

| 2003 | 76 (14.1) | 37 (6.9) | 421 (78.3) | 4 (0.7) | 538 |

| 2004 | 95 (18.1) | 71 (13.5) | 356 (67.9) | 2 (0.4) | 524 |

| 2005 | 123 (18.1) | 133 (19.6) | 420 (61.7) | 3 (0.6) | 679 |

| 2006 | 139 (18.7) | 173 (23.3) | 422 (56.9) | 8 (1.1) | 742 |

| 2007 | 150 (19.5) | 221 (28.7) | 395 (51.3) | 4 (0.5) | 770 |

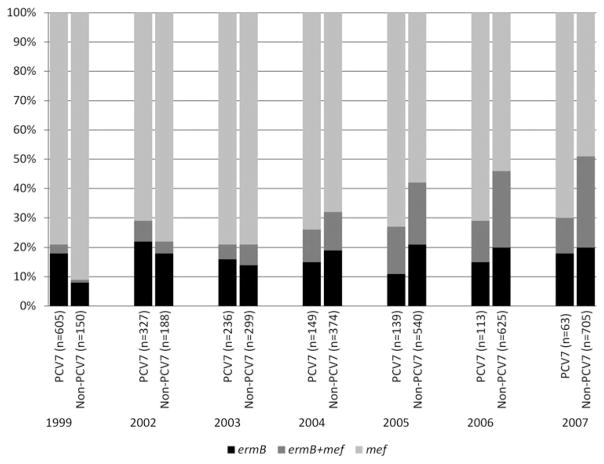

Changes in the prevalence of these mechanisms of erythromycin resistance among invasive isolates were closely related to changes in serotype distribution (Fig. 1). The mef-only genotype decreased slightly in prevalence, but still remained the predominant mechanism among PCV7 serotype isolates across the years in the study. The ermB + mef genotype increased somewhat among PCV7 serotype isolates due to the relative number of 19F isolates (data not shown), but remained as a minor proportion. In contrast, among non-PCV7 serotype isolates in our study, the proportion of mef-only isolates declined from 91.3% in 1999 to 48.5% in 2007 ( p < 0.0001), while the proportion of ermB + mef isolates increased as a function of 19A emergence from 0.7% in 1999 to 31.3% in 2007 ( p < 0.0001). Most isolates positive for ermB + mef from 2007 were serotype 19A (85.5%). The proportion of ermB-only isolates also increased among non-PCV7 serotypes, but not significantly.

FIG. 1.

Changes in distribution of the two major macrolide resistance determinants among PCV7 versus non-PCV7 serotypes.

Thirty-seven macrolide-resistant isolates were negative for both ermB- and mef-mediated mechanisms and were therefore screened for the presence of ermA (subclass ermTR), cfr, lsaC, and vgaA genes, as well as changes (relative to TIGR4) in genes encoding L4 (rplD) and L22 (rplV), and in the 23S rRNA. Three isolates were positive for ermA (subclass ermTR) and 25 had changes in the 23S rRNA or the ribosomal proteins (L4 and L22). No changes were found in nine of the isolates. None of the isolates contained any of the other MLS resistance genes tested, and clindamycin resistance was not inducible in any of the clindamycin-susceptible strains (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chromosomal Changes Associated with MLS Resistance Among Isolates Not Containing ermB and/or mef (n = 37)

| Year | Strain ID | Serotype | ERY | CLDa | Q-Db | Changes in L4c,d | Changes in L22c,d | Changes in 23S rRNAc | Othere |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 3802-99 | 19A | > 32 | 0.12 | 1.5 | 69GTG71 to TPS, E13Q, E30Q, V88I, G98A, A128S, S130E | |||

| 1999 | 6275-99 | 19A | > 32 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 69GTG71 to TPS, E13Q, E30Q, V88I, G98A, A128S, S130E | |||

| 2002 | 5087-03 | 19A | > 32 | 0.12 | 1 | 69GTG71 to TPS, E13Q, E30Q, V88I, G98A, A128S, S130E | |||

| 2002 | 5486-02 | 23F | 2 | < 0.03 | 1 | E30K 63KPWRQKTGTGRA73 | |||

| 2002 | 5001-02 | 22F | 2 | 0.12 | 8 | S112L | 102KRTAHITRTAHIVA110 | ||

| 2005 | 5309-05 | 22F | 4 | 0.06 | 24 | S112L | 102KRTAHITKRTAHITVA110 | ||

| 2007 | 6466-07 | 19A | 16 | 0.25 | > 32 | 85PMKRFRPPMKRFRPR92T85P | |||

| 1999 | 2009219579 | 35F | 2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | A2061G | |||

| 1999 | 3494-00 | 19A | 16 | 0.5 | 1 | A2061G | |||

| 1999 | 4397-99 | 004 | 32 | 1 | 1 | A2061G | |||

| 1999 | 1361-00 | 06B | > 32 | 1 | 1 | A2061G | |||

| 1999 | 4056-00 | 06B | > 32 | 2 | 1.5 | A2061G | |||

| 1999 | 7783-99 | 09N | > 32 | 2 | 1 | A2061G | |||

| 1999 | 5667-99 | 06B | > 32 | > 2 | 2 | A2061G | |||

| 2003 | 6752-04 | 10A | > 32 | 0.25 | 1 | A2061G | |||

| 2003 | 8297-04 | 35B | > 32 | 2 | 1 | A2061G | |||

| 2004 | 9764-04 | 034 | 32 | 1 | 1 | A2061G | |||

| 2005 | 3662-06 | 06C | > 32 | > 2 | 1.5 | A2061G | |||

| 2005 | 7853-05 | 06A | > 32 | 2 | 2 | A2061G | |||

| 2006 | 5473-07 | 22F | > 32 | 2 | 2.0 | S112L | A2061G | ||

| 2006 | 6549-07 | 17F | 32 | 1 | 0.5 | A2061G | |||

| 2006 | 7509-06 | 15C | > 32 | > 2 | 2 | A2061G | |||

| 2006 | 8043-06 | 23A | > 32 | 2 | 1.5 | A2061G | |||

| 2007 | 2010200843 | 09N | 32 | 1 | 2 | A2061G | |||

| 2007 | 7948-07 | 034 | > 32 | > 2 | 1.5 | A2061G | |||

| 2007 | 2008008613 | 19A | 32 | 1 | 1 | ermA + | |||

| 2006 | 7541-06 | 003 | > 32 | 2 | 1 | ermA + | |||

| 2004 | 4336-05 | 038 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | ermA + | |||

| 1999 | 6306-99 | 24F | 16 | 1 | 0.5 | None | |||

| 2006 | 7582-06 | 23A | 32 | 2 | 1 | None | |||

| 2003 | 7995-03 | 07F | 16 | 0.12 | 0.5 | None | |||

| 1999 | 4066-00 | 014 | 16 | 1 | 1 | None | |||

| 2006 | 4882-07 | 07F | 4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | None | |||

| 2006 | 7701-07 | 35F | > 32 | 2 | 1.5 | None | |||

| 2003 | 2003000312 | 10A | > 32 | 2 | 2 | None | |||

| 2002 | 2009214597 | 06A | > 32 | 1 | 0.5 | None | |||

| 1999 | 5272-03 | 001 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | None |

Clindamycin resistance was not inducible in any of the clindamycin-susceptible strains.

Determined by Etest.

Relative to TIGR4.

Insertions are underlined.

ermT, ermA (subclass ermTR), cfr, lsaC, and vgaA.

CLD, clindamycin; ERY, erythromycin; MLS, macrolides/lincosamides/streptogramin; Q-D, quinupristin–dalfopristin (Synercid).

Of the 25 isolates with ribosomal changes, 18 isolates had an A to G substitution at position 2061 (A2059 in Escherichia coli) in the 23S rRNA, 7 had substitutions or insertions in L4, 3 of those with multiple changes, and 3 isolates had insertions in L22.

Since all 3 isolates with insertions in L22 were also resistant to Q-D, we screened an additional 18 Q-D nonsusceptible isolates from ABCs (submitted from 1996 to 2010). Six of them had insertions similar to those previously observed and one had a substitution in L22. Three isolates had insertions, and two isolates had substitutions in L4. Lastly, one isolate had a C-to-G change at position 2613 (C2611 in E. coli) and another had an A-to-C change at position 2060 (A2058 in E. coli) in the 23S rRNA. Incidentally, one of the isolates was positive for both ermB and mef, and one was positive for mef only. In three of these isolates, the potential mechanisms were not apparent (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes Associated with Quinupristin–Dalfopristin Nonsusceptibility

| Year | Strain ID | Serotype | ERY | CLD | Q-Da | Changes in L4c,d | Changes in L22c,d | Changes in 23S rRNAc | Othere |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 3179-97 | 09V | 4 | 0.12 | 2.0 | ||||

| 1997 | 1095-99 | 11A | > 8 | 4 | 2.0 | A2060C | |||

| 2007 | 2008236056 | 19A | > 32 | > 2 | 2.0 | e + m | |||

| 2007 | 2008227074b | 09N | 1 | 0.06 | 3.0 | Q67R R72G | |||

| 2000 | 4339-00 | 19F | 0.5 | 0.06 | 4.0 | 63KPWRQKGKGTGRAR74 | |||

| 2001 | 5663-01 | 19F | 32 | 0.06 | 4.0 | 63KPWRQKGSQKGTGRAR74 | m | ||

| 2003 | 6766-04 | 12F | 0.25 | ≤ 0.03 | 4.0 | 63KPWRPWRQKGTGRAR74 | |||

| 2008 | 2008237895 | 07F | 0.5 | 0.06 | 4.0 | 78AFANEGPTIAFANEGPTM86 | |||

| 2000 | 7697-03 | 23F | 1 | 0.12 | 8.0 | E30K | |||

| 2001 | 2009216547 | 014 | 2 | 0.06 | 8.0 | 102KRTAHITRTAHITVA110 | |||

| 2001 | 6434-01 | 06A | 2 | 0.06 | 8.0 | 102KRTAHITKRTAHIVA110 | |||

| 1996 | 0571-97 | 004 | 1 | 0.06 | 12.0 | 102KRTAHITKRTAHITVA110 | |||

| 2007 | 7799-07 | 11A | > 32 | 1 | 12.0 | C2613G | |||

| 2010 | 2010223420 | 19A | 4 | 0.06 | 12.0 | 102KRTAHITVRTAHITVA110 | |||

| 2008 | 2009208197 | 16F | 1 | 0.06 | 16.0 | 85TMKRFRPRASFRPRAK94 | |||

| 2000 | 6356-00 | 06A | 4 | 0.06 | 32.0 | R103C | |||

| 1995 | 3262-95 | 06A | 2 | ≤ 0.03 | 12.0 | None | |||

| 2001 | 5951-01 | 004 | 1 | 0.06 | 8.0 | None |

Determined by Etest.

This strain is nonsusceptible to linezolid (minimum inhibitory concentration = 4 μg/ml).

Relative to TIGR4.

Insertions are underlined.

ermT, ermA (subclass ermTR), ermB (e), mef (m), cfr, lsaC, and vgaA.

Overall, we found a total of 28 changes in the 23S rRNA and the ribosomal proteins L4 and L22 (relative to TIGR4), 11 of which have never been reported (Table 4). In addition, we found four changes relative to TIGR4 that correspond to the natural variants of L4, L22, and 23S rRNA and do not correlate with changes in macrolide susceptibility: an S20N substitution in L4, an I39T substitution in L22, plus a 683AA684 to CC substitution, and a U676C substitution in domain II of the 23S rRNA.

Table 4.

Summary of Alterations Found in L4, L22, and 23s rRNA, Among ERY-Resistant (erm - /mef -, n = 37) and Q/D Nonsusceptible Isolates (n = 18)

| Gene | Mutationa | Observed phenotypeb | Reported phenotypeb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rplD/L4 | E13Q, E30Q, V88I, G98A, A128S, S130E | See notes c and d | No resistance | 56 |

| E30K | Q-D | M | 54 | |

| S112L | See note d | This study | ||

| Q67R + R72G | Q-D LZD | LZD | 14 | |

| 69GTG71 to TPS | MSB | ML, M, MSB | 17, 50, 56 | |

| 63KPWRQKTGTGRAR74 | M | This study | ||

| 63KPWRQKGKGTGRAR74 | Q-D | ERY-I AZI-R | 37 e | |

| 63KPWRQKGSQKGTGRAR74 | M Q-D | This study | ||

| 63KPWRPWRQKGTGRAR74 | Q-D | This study | ||

| rplV/L22 | R103C | M Q-D | This study | |

| 102KRTAHITRTAHIVA110 | M Q-D | M Q-D | 29 | |

| 102KRTAHITRTAHITVA110 | M Q-D | ML, M, M Q-D | 17, 40 | |

| 102KRTAHITKRTAHIVA110 | M Q-D | M Q-D | 6 | |

| 102KRTAHITKRTAHITVA110 | M Q-D | This study | ||

| 102KRTAHITVRTAHITVA110 | M Q-D | This study | ||

| T85P | See note 4 | This study | ||

| 85PMKRFRPPMKRFRPRAK94 | M Q-D | This study | ||

| 85TMKRFRPRASFRPRAK94 | M Q-D | This study | ||

| 76SEAFANEGPTIAFANEGPTM86 | M Q-D | This study | ||

| 23s d. V | A2061G (2059 in Escherichia coli) | M, MLSB | ML, MLSB, MSB | 16, 49, 50, 54 |

| C2613G (2611 in E. coli) | M Q-D | M, M Q-D | 16, 49, 52 | |

| A2060C (2058 in E. coli) | MLSB | ML, M | 33, 42, 52e |

Insertions are underlined.

“Observed phenotype” refers to this study, while “Reported phenotype” refers to phenotypes observed in previous reports.

These changes were found in combination with the 69GTG71 to TPS substitution.

Only found in combination with other changes, its role in resistance is unclear.

These reports pertain to other bacterial species. Our study is the first to report these changes in Streptococcus pneumoniae.

AZI, azithromycin; ERY, erythromycin; LZD, linezolid; L, lincosamides; M, macrolides; SB, streptogramin B; Q-D, quinupristin–dalfopristin (Synercid).

We also identified three isolates that were clindamycin susceptible in spite of carrying the ermB gene. They were checked by the D-zone disk diffusion test and broth microdilution, and resistance was not found to be inducible. The ermB structural gene was sequenced and no changes were found. This was also the case for one of the isolates carrying ermA (4336-05), where clindamycin resistance was not inducible, and no changes were found in the ermA structural gene sequence, suggesting a defect in gene expression.

Discussion

PCV7 implementation had a marked impact on the distributions of macrolide resistance determinants among invasive isolates in the United States, due to decreases in vaccine-targeted strains and increases in certain nonvaccine serotype strains. Before the introduction of PCV7, the majority of mef-only isolates among the macrolide-resistant isolates in the study were associated with serotype 14 (64.4%), which was the most common serotype among all macrolide-resistant isolates in the study (44.5%). After the introduction of PCV7, the proportion of serotype 14 among the study isolates declined rapidly to 21.7% in 2002 and to 2.2% by 2007, contributing to the decrease of the mef-only genotype among macrolide-resistant pneumococci from 80.2% in 1999 to only 51.3% in 2007. In contrast, the proportion of ermB + mef isolates increased from 0.7% in 1999 to 31.3% in 2007, mainly driven by the emergence of macrolide-resistant serotype 19A in the post-PCV7 period. Serotype 19A accounted for 3.4% and 42.3% of pneumococcal macrolide resistance in 1999 and 2007, respectively. During 2007, 85.5% isolates positive for ermB + mef were of serotype 19A.

Population-based surveillance in the United States revealed that 82% of penicillin-resistant invasive serotype 19A isolates recovered during 2007 belonged to clonal complex CC320/27119A, and the majority of these were also resistant to macrolides (96%) and lincosamides (79%).3 It should be noted that CC320/271 includes the Taiwan19F-14 clone, which is the likely ancestral strain of this complex and also carries ermB and mef. Serotype19A and its associated high-level resistance has already decreased dramatically within ABCs surveillance areas following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar13; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals) in February of 2010 (unreported data), and is likely to continue to decrease, as also evidenced by early reports of decreased carriage of 19A and decreased rates of IPD caused by 19A.12,30,44 MLSB-type resistance within non-PCV13 serotype 15A, seen here associated with ermB, modestly increased in the post-PCV7 period due to the increase in multilocus sequence-type ST63.24 In the post-PCV13 period, these and other nonvaccine serotype-resistant strains could potentially continue to emerge, possibly benefitting from the removal of PCV13 serotypes from the carriage reservoir.

Aside from the changes in serotype and the ermB- and/or mef-mediated mechanisms, we also identified potentially important resistance-associated changes within the ribosomal proteins L4 and L22 and the 23S rRNA. Eleven of the 28 changes identified have not been previously described and an additional 2 have been reported in other bacterial species, but not in S. pneumoniae.

Seven different changes were found in a highly conserved region of L4 (Table 4), 63KPWRQKGTGRAR74, including three previously unreported insertions (ranging from 3 to 12 bp) associated with macrolide and/or Q-D resistance, and one insertion (KG after position 69) previously reported to confer resistance to azithromycin, but not erythromycin nor Q-D, in Streptococcus pyogenes.37 Similar insertions have been reported in S. pneumoniae and other gram-positive species in association with resistance to macrolides and streptogramins.23 We also found three substitutions, including a 69GTG71 to TPS substitution that has been previously shown to confer resistance to macrolides, and streptogramin B,17,50,54 and to telithromycin as well when combined with the presence of ermB55; plus two substitutions, Q67R and R72G in a Q-D, which were described in a previous report.14 Although previous linezolid nonsusceptible clinical S. pneumoniae isolates have only been associated with deletions in L4,17,55 similar substitutions have been reported in laboratory-derived mutants of pneumococcal strains22 and clinical isolates of other species.36 In addition, a Ser-to-Leu substitution was found at position 112, but only in combination with other changes.

In L22, we found a total of 10 changes in conserved regions of the C-terminal sequence (Table 4), including 2 substitutions and 8 insertions (ranging from 15 to 27 bp), associated with macrolide and Q-D resistance. Five of the insertions were in the region 102KRTAHITVA110; three have been previously reported,6,17,29,40 and two newly observed insertions are very similar as well (KRTAHIT and VRTAHIT). The three remaining insertions were in a region where an insertion has been previously reported in macrolide-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates (85PMKRFRPR92).43 Deletions have also been reported in this region of the Staphylococcus aureus L22 protein in association with Q-D resistance.38 The two substitutions T85P and R103C have not been previously reported.

Mutations in primary rRNA sequence have been found to play an important role in antibiotic resistance and there is growing evidence pointing to their role in MLS resistance.13,52 In this study, three potentially resistance-conferring mutations were found in the peptidyltransferase loop of the 23S rRNA of 20 invasive isolates. Position 2611 (E. coli numbering) is important in maintaining the stem preceding the single-stranded portion of the peptidyltransferase loop containing positions A2058 and A2059,5,35 and a C-to-G substitution at this position has been previously reported to confer resistance to macrolides and Q-D16; this substitution was observed in one of our isolates with the same phenotype (7799-07). Another isolate in our study carried an A2060C (A2058 in E. coli) substitution that has not been previously reported in S. pneumoniae, but has been reported in Mycobacterium intracellulare,52 Mycoplasma pneumoniae,42 and C. jejuni,33 in association with an MLSB phenotype. The isolate in our study was found to be resistant to erythromycin and clindamycin and nonsusceptible to Q-D; the elevated Q-D MIC (2 μg/ml) is likely explained by resistance to the streptogramin B unit (quinupristin) of Q-D. In addition, 18 isolates carried an A2061G (A2059 in E. coli) substitution that has been frequently reported in association with an ML, MLSB, or MSB phenotype,16,49,50 which are the same phenotypes we observed. It has been previously suggested that the different phenotypes and levels of resistance associated with this substitution depend on the number of 23S rRNA alleles that are mutated.16 However, another study on a large population of isolates argued against this and instead suggested that differential expression due to environmental pressure may be the explanation for these phenomena.17 Since we did not individually amplify the four alleles present in S. pneumoniae nor measured their expression, we are unable to draw conclusions either way, but believe that both possibilities merit further investigation.

Future plans include performing transformation assays to determine the role of the 13 changes found in this study, as well as further characterization by whole genome sequencing of the isolates where the mechanism of resistance remains unexplained.

Acknowledgments

The contributions of all of the members of the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network made this work possible. The authors are also grateful to members of the CDC’s Streptococcus Laboratory for assisting with the DNA sequencing as well as performing serotyping and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The authors thank Dr. James Jorgensen and his laboratory group for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of all isolates other than those recovered in Georgia and Minnesota. They also gratefully acknowledge the Minnesota Department of Public Health laboratory for pneumococcal serotyping and susceptibility testing of all isolates recovered in Minnesota. They thank the members of the Klugman laboratory at Emory for their part in the initial PCR screening of the isolates.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no actual or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Surveillance Reports. Atlanta, GA: [accessed August 28th, 2013]. Available at www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/surv-reports.html. (Online.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Applied Biosystems. BigDye® Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit Protocol. Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beall BW, Gertz RE, Hulkower RL, Whitney CG, Moore MR, Brueggemann AB. Shifting genetic structure of invasive serotype 19A pneumococci in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1360–1368. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bley C, van der Linden M, Reinert RR. mef(A) is the predominant macrolide resistance determinant in Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes in Germany. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannone JJ, Subramanian S, Schnare MN, Collett JR, D’Souza LM, Du Y, Feng B, Lin N, Madabusi LV, Müller KM, Pande N, Shang Z, Yu N, Gutell RR. The comparative RNA web (CRW) site: an online database of comparative sequence and structure information for ribosomal, intron, and other RNAs. BMC Bioinform. 2002;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cattoir V, Merabet L, Legrand P, Soussy CJ, Leclercq R. Emergence of a Streptococcus pneumoniae isolate resistant to streptogramins by mutation in ribosomal protein L22 during pristinamycin therapy of pneumococcal pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:1010–1012. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Pneumococcal Disease among Infants and Young Children. MMWR. 2000;49(RR-9):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of Pneumococcal Disease Among Infants and Children—Use of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine and 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine. MMWR. 2010;59(RR-11):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI document M07-A9. CLSI; Wayne, PA: 2012. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard—Ninth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI document M02-A11. CLSI; Wayne, PA: 2012. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests; Approved Standard—Eleventh Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI document M100-S23. CLSI; Wayne, PA: 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 23rd informational supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagan R, Patterson S, Juergens C, Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Porat N, Gurtman A, Gruber WC, Scott DA. Comparative immunogenicity and efficacy of 13-valent and 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in reducing nasopharyngeal colonization: a randomized double-blind trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:952–962. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Depardieu F, Courvalin P. Mutation in 23S rRNA responsible for resistance to 16-membered macrolides and streptogramins in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:319–323. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.319-323.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong WI, Chochua S, McGee L, Jackson D, Klugman KP, Vidal JE. Mutations within the rplD Gene of Linezolid-Nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:2459–2462. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02630-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell DJ, Morrissey I, Bakker S, Felmingham D. Molecular characterization of macrolide resistance mechanisms among Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes isolated from the PROTEKT 1999–2000 study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:39–47. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrell DJ, Douthwaite S, Morrissey I, Bakker S, Poehlsgaard J, Jakobsen L, Felmingham D. Macrolide resistance by ribosomal mutation in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the PROTEKT 1999–2000 study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1777. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1777-1783.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrell D, Morrissey I, Bakker S, Buckridge S, Felmingham D. In vitro activities of telithromycin, linezolid, and quinupristin-dalfopristin against Streptococcus pneumoniae with macrolide resistance due to ribosomal mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3169–3171. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3169-3171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell DJ, Jenkins SG, Brown SD, Patel M, Lavin BS, Klugman KP. Emergence and spread of Streptococcus pneumoniae with erm(B) and mef(A) resistance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:851–858. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.050222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell DJ, File TM, Jenkins SG. Prevalence and antibacterial susceptibility of mef(A)-positive macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae over 4 years (2000 to 2004) of the PROTEKT US Study. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:290–293. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01653-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrell DJ, Klugman KP, Pichichero M. Increased antimicrobial resistance among nonvaccine serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the pediatric population after the introduction of 7-valent pneumococcal vaccine in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:123. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000253059.84602.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrell DJ, Couturier C, Hryniewicz W. Distribution and antibacterial susceptibility of macrolide resistance genotypes in Streptococcus pneumoniae: PROTEKT Year 5 (2003–2004) Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng J, Lupien A, Gingras H, Wasserscheid J, Dewar K, Légaré D, Ouellette M. Genome sequencing of linezolid-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants reveals novel mechanisms of resistance. Genome Res. 2009;19:1214–1223. doi: 10.1101/gr.089342.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franceschi F, Kanyo Z, Sherer EC, Sutcliffe J. Macrolide resistance from the ribosome perspective. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2004;4:177–191. doi: 10.2174/1568005043340740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gertz RE, Jr, Li Z, Pimenta FC, Jackson D, Juni BA, Lynfield R, Jorgensen JH, da Carvalho MG, Beall BW Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. Increased penicillin nonsusceptibility of nonvaccine-serotype invasive pneumococci other than serotypes 19A and 6A in post-7-valent conjugate vaccine era. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:770–775. doi: 10.1086/650496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirakata Y, Mizuta Y, Wada A, Kondoh A, Kurihara S, Izumikawa K, Seki M, Yanagihara K, Miyazaki Y, Tomono K, Kohno S. The first telithromycin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolate in Japan associated with erm(B) and mutations in 23S rRNA and riboprotein L4. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007;60:48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyde TB, Gay K, Stephens DS, Vugia DJ, Pass M, Johnson S, Barrett NL, Schaffner W, Cieslak PR, Maupin PS, Zell ER, Jorgensen JH, Facklam RR, Whitney CG Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network. Macrolide resistance among invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates. JAMA. 2001;286:1857–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins SG, Brown SD, Farrell DJ. Trends in antibacterial resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in the USA: update from PROTEKT US Years 1–4. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2008;7:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins S, Farrell D. Increase in pneumo-coccus macrolide resistance, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1260–1264. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones RN, Farrell DJ, Morrissey I. Quinupristin-dalfopristin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: novel L22 ribosomal protein mutation in two clinical isolates from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2696. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2696-2698.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan SL, Barson WJ, Lin PL, Romero JR, Bradley JS, Tan TQ, Hoffman JA, Givner LB, Mason EO. Early trends for invasive pneumococcal infections in children after the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:203–207. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318275614b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kehrenberg C, Schwarz S. Distribution of florfenicol resistance genes fexA and cfr among chloramphenicol-resistant Staphylococcus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1156–1163. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1156-1163.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyaw M, Lynfield R, Schaffner W, Craig AS, Hadler J, Reingold A, Thomas AR, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Farley MM, Facklam RR, Jorgensen JH, Besser J, Zell ER, Schuchat A, Whitney CG Active Bacterial Core Surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network. Effect of introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1455–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladely SR, Meinersmann RJ, Englen MD, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Harrison MA. 23S rRNA gene mutations contributing to macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2009;6:91–98. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambertsen L, Ekelund K, Hansen D, Kaltoft M, Christensen JJ, Hammerum AM. Erythromycin resistance caused by erm(A) subclass erm(TR) in a Danish invasive pneumococcal isolate: are erm(A) pneumococcal isolates overlooked? Scand. J Infect Dis. 2008;40:584–587. doi: 10.1080/00365540701854717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Resistance to macrolides and related antibiotics in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2727–2734. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2727-2734.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Long KS, Vester B. Resistance to linezolid caused by modifications at its binding site on the ribosome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:603–612. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05702-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malbruny B, Nagai K, Coquemont M, Bozdogan B, Andrasevic AT, Hupkova H, Leclercq R, Appelbaum PC. Resistance to macrolides in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes due to ribosomal mutations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:935–939. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malbruny B, Canu A, Bozdogan B, Fantin B, Zarrouk V, Dutka-Malen S, Feger C, Leclercq R. Resistance to quinupristin-dalfopristin due to mutation of L22 ribosomal protein in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2200–2207. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2200-2207.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malbruny B, Werno AM, Murdoch DR, Leclercq R, Cattoir V. Cross-resistance to lincosamides, streptogramins A, and pleuromutilins due to the lsa(C) gene in Streptococcus agalactiae UCN70. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1470–1474. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01068-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musher DM, Dowell ME, Shortridge VD, Jorgensen JH, Le Magueres P, Krause KL. Emergence of macrolide resistance during treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:630–631. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200202213460820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novotna G, Janata J. A new evolutionary variant of the streptogramin A resistance protein, Vga(A)LC, from Staphylococcus haemolyticus with shifted substrate specificity towards lincosamides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4070–4076. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00799-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peuchant O, Ménard A, Renaudin H, Morozumi M, Ubukata K, Bébéar CM, Pereyre1 S. Increased macrolide resistance of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in France directly detected in clinical specimens by real-time PCR and melting curve analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:52–58. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pihlajamäki M, Jalava J, Huovinen P, Kotilainen P Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Antimicrobial resistance of invasive pneumococci in Finland in 1999–2000. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1832–1835. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1832-1835.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richter SS, Heilmann KP, Dohrn CL, Riahi F, Diekema DJ, Doern GV. Pneumococcal serotypes before and after introduction of conjugate vaccines, United States, 1999–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1074–1083. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.121830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shortridge VD, Zhong P, Cao Z, Beyer JM, Almer LS, Ramer NC, Doktor SZ, Flamm RK. Comparison of in vitro activities of ABT-773 and telithromycin against macrolide-susceptible and -resistant streptococci and staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:783–786. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.783-786.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutcliffe J, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes resistant to macrolides but sensitive to clindamycin: a common resistance pattern mediated by an efflux system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1817–1824. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Syrogiannopoulos GA, Grivea IN, Tait-Kamradt A, Katopodis GD, Beratis NG, Sutcliffe J, Appelbaum PC, Davies TA. Identification of an erm(A) erythromycin resistance methylase gene in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in Greece. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:342. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.342-344.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tait-Kamradt A, Davies T, Cronan M, Jacobs MR, Appelbaum PC, Sutcliffe J. Mutations in 23S rRNA and ribosomal protein L4 account for resistance in pneumococcal strains selected in vitro by macrolide passage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2118–2125. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2118-2125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tait-Kamradt A, Davies T, Appelbaum PC, Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Petitpas J, Wondrack L, Walker A, Jacobs MR, Sutcliffe J. Two new mechanisms of macrolide resistance in clinical strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae from Eastern Europe and North America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3395–3401. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3395-3401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Li D, Song L, Liu Y, He T, Liu H, Wu C, Schwarz S, Shen J. First report of the multi-resistance gene cfr in Streptococcus suis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:4061–4063. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00713-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:577–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Lynfield R, Reingold A, Cieslak PR, Pilishvili T, Jackson D, Facklam RR, Jorgensen JH, Schuchat A Active Bacterial Core Surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1737–1746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wierzbowski AK, Nichol K, Laing N, Hisanaga T, Nikulin A, Karlowsky JA, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG. Macrolide resistance mechanisms among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated over 6 years of Canadian Respiratory Organism Susceptibility Study (CROSS) (1998–2004) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:733–740. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolter N, Smith AM, Farrell DJ, Schaffner W, Moore M, Whitney CG, Jorgensen JH, Klugman KP. Novel mechanism of resistance to oxazolidinones, macrolides, and chloramphenicol in ribosomal protein L4 of the pneumococcus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3554–3557. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3554-3557.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolter N, Smith AM, Low DE, Klugman KP. High-level telithromycin resistance in a clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1092–1095. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01153-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woodbury RL, Klammer KA, Xiong Y, Bailiff T, Glennen A, Bartkus JM, Lynfield R, Van Beneden C, Beall BW Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. Plasmid-Borne erm(T) from invasive, macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1140–1143. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01352-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]