Abstract

Background and Aims:

Transurethral resection of the prostate is a commonly performed urological procedure in elderly men with spinal anaesthesia being the technique of choice. Use of low-dose spinal anesthetic drug with adjuvants is desirable. This study compares the sensorimotor effects of addition of buprenorphine or dexmedetomidine to low-dose bupivacaine.

Methods:

Sixty patients were randomly allocated to three different groups. All received 1.8 mL 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine intrathecally. Sterile water (0.2 mL) or buprenorphine (60 μg) or dexmedetomidine (5 μg) was added to control group (Group C), buprenorphine group (Group B), and dexmedetomidine group (Group D), respectively. Time to the first analgesic request was the primary objective, and other objectives included the level of sensory-motor block, time to two-segment regression, time to S1 sensory regression and time to complete motor recovery. ANOVA and post hoc test were used for statistical analysis. The value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

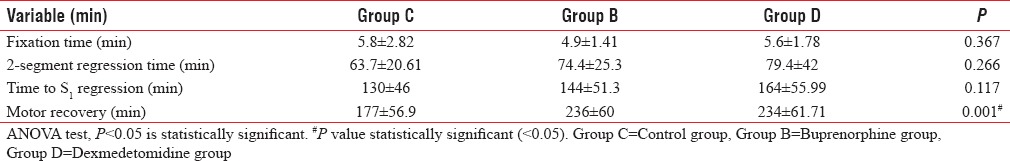

All sixty patients completed the study. Postoperative analgesia was not required in the first 24 h in a total of 10 (50%), 12 (60%) and 15 (75%) patients in groups C, B, and D, respectively. Time to S1 regression was 130 ± 46 min (Group C), 144 ± 51.3 min (Group B) and 164 ± 55.99 min (Group D), P = 0.117. Time to complete motor recovery was 177 ± 56.9 min (Group C), 236 ± 60 min (Group B) and 234 ± 61.71 min (Group D), P < 0.001.

Conclusion:

Addition of buprenorphine (60 μg) or dexmedetomidine (5 μg) to intrathecal bupivacaine for transurethral resection prolongs the time to the first analgesic request with comparable recovery profile.

Keywords: Anaesthesia, buprenorphine, dexmedetomidine, intrathecal, transurethral resection of prostate

INTRODUCTION

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is a commonly performed procedure in elderly male patients.[1] Postoperatively, these patients often suffer from bladder spasm associated with the use of a transurethral balloon to prevent bleeding from the prostatic bed or capsule.[2,3] Therefore, there is a need to develop anesthetic techniques that extend postoperative analgesia without compromising patient safety. Spinal anesthesia is the commonly used technique for these procedures as this is the quickest, most predictable and reliable form of regional anaesthesia. Besides, the patients remain awake during the surgical procedure enabling early identification of complications of TURP such as transurethral resection syndrome involving osmolar disturbances, fluid overload or water intoxication. A sensory level block of not more than T10 is desirable to detect the complications such as bladder perforation. Unfortunately, this level of the block with only intrathecal local anesthetics may not achieve an extended duration of postoperative analgesia. Use of higher doses of local anesthetics to achieve this may result in circulatory disturbances that can be difficult to manage as these patients are usually elderly and hence may have varying degrees of organ damage or associated systemic illness. However, a combination of low-dose local anesthetics along with other adjuvants can prolong the postoperative analgesia. Hence, this has become an attractive option. Several adjuvants such as opioids and α2 agonists have been studied in combination with intrathecal local anesthetics to improve the postoperative analgesia without compromising patient safety.[4,5] This study evaluates the sensorimotor effects of addition of buprenorphine or dexmedetomidine to low-dose intrathecal bupivacaine in patients undergoing TURP.

METHODS

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee for the study and written informed consent from all the participants, this double-blinded, randomized, prospective study was commenced. Patients belonging to American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status I, II or III scheduled to undergo TURP under spinal anaesthesia were included in the study. Patients with a history of previous spinal surgery; infection at the injection site; hypersensitivity to amide local anesthetics, buprenorphine or dexmedetomidine; mental disturbance or neurologic disease were excluded from the study. All patients enrolled in the study were advised to remain nil per oral for a minimum of 3 h to clear fluids and 6 h to solids and liquids and were premedicated with oral alprazolam 0.25 mg on the night before surgery.

On the morning of surgery, patients were allocated to one of three groups based on a computer-generated list of random numbers. Patients in Group C (Control Group) received 1.8 mL 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 0.2 mL sterile water intrathecally. Patients in Group B (Buprenorphine Group) received 1.8 mL 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 0.2 mL buprenorphine (60 μg) intrathecally. Buprenorphine was loaded undiluted from the ampoule of buprenorphine-containing 300 μg/mL. Patients in Group D (dexmedetomidine Group) received 1.8 mL 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 0.2 mL dexmedetomidine (5 μg) intrathecally. From the ampoule of the dexmedetomidine (100 μg/mL), 0.25 mL (25 μg) was drawn into an insulin syringe. This 25 μg dexmedetomidine was further diluted with sterile water to make it up to 1 mL, i.e., 2.5 μg/division. Two divisions of dexmedetomidine (0.2 mL) diluted in this manner (5 μg) was then added to 1.8 mL hyperbaric bupivacaine. An insulin syringe was used to accurately draw 0.2 mL adjuvant drug in each group. The same was added to 1.8 mL 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine to make a total volume of 2.0 mL.

An anesthesiologist not involved in the study prepared the study drug under aseptic precautions, performed the subarachnoid block and administered the study drug. Another anesthesiologist who was unaware of the study drug administered recorded the following study parameters: Hemodynamic parameters, details of sensory and motor blockade, anxiety scores, amount of midazolam injected, time to the first analgesic request by the patient in the postoperative period and any complications during the study.

Once the patient was shifted to the operating room, the electrocardiogram monitoring (leads II and V5), noninvasive blood pressure and pulse oximeter were attached and baseline vitals recorded. The anxiety level of the patient was assessed using the Ramsay Sedation Score (RSS) at this point, every 15 min during intraoperative period and every hour in the postoperative period until completion of the study. Midazolam was given intravenously in 0.5 mg increments to patients with RSS 1 to titrate the RSS between 2 and 3. Intravenous (IV) access was established, and an infusion of 0.9% NaCl started at a rate of 20 ml/h following an initial bolus of 200 mL. The patient was positioned in the right lateral position and lumbar puncture performed under aseptic precautions using either a 23-guage or a 25-guage Quincke-Babcock spinal needle in the L2/L3 or L3/L4 interspace. After obtaining free flow of cerebrospinal fluid, the study drug was injected intrathecally over a period of 10 s. The bevel was directed cephalad during injection of the drug in all patients. The patient was turned supine immediately after performing the block and remained in the supine position until the sensory block reached the highest dermatomal level. Motor block was assessed at the time of reaching peak sensory level, and this was considered as the maximum level motor block. All patients were then placed in the lithotomy position and surgery commenced.

Oxygen was administered continuously at 5 L/min via a face mask. The level of sensory block was determined using the hub of a sterile 22-gauge needle in the midline, and dermatomal level assessed every 2 min from completion of injection until the assessed sensory level remained stable for four consecutive assessments. Testing was conducted every 10 min thereafter until two-segment regression was noticed. Further testing was performed at 20 min intervals in the recovery room until recovery of the S1 dermatome. All times were recorded from the time of completion of the intrathecal injection. The highest dermatomal level of sensory blockade, the time to reach this level, motor blockade at the time of reaching peak sensory level, the time to two-segment regression, and the time to S1 sensory regression were recorded. Motor block was assessed using the Bromage scale (0: No motor block; 1: Hip blocked; 2: Hip and knee blocked; and 3: Hip, knee, and foot blocked). Duration of motor block was considered until the time when Bromage score returned to 0. Time to the first analgesic request was considered the primary objective of the study.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure and heart rate (HR) were recorded every 3 min for the first 15 min following spinal anaesthesia, and then every 5 min until the end of surgery. Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg or 30% decrease from the baseline) and bradycardia (HR <45 beats/min) were treated with IV bolus of mephentermine 3 mg and atropine 0.6 mg, respectively. Adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, shivering, pruritus, respiratory depression, and transient neurological symptoms were recorded. The duration of surgery was noted. The patients were instructed to tell the staff nurse whenever they felt the need for an analgesic. The staff nurse noted the time to first analgesic request from the patient. Tramadol IV 50 mg and paracetamol IV 1 g was the postoperative rescue analgesics.

Based on a pilot study that was conducted on ten patients in each group, to find a difference of at least 2 h between the groups for time to first analgesic request, a sample size of 18 per group was needed for a power of 80% at 95% confidence interval. To compensate for any losses, 20 patients/group were assigned. ANOVA test was used to assess the statistical difference between the three groups and intergroup comparison was done using post hoc test between individual groups for all main study variables. The value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

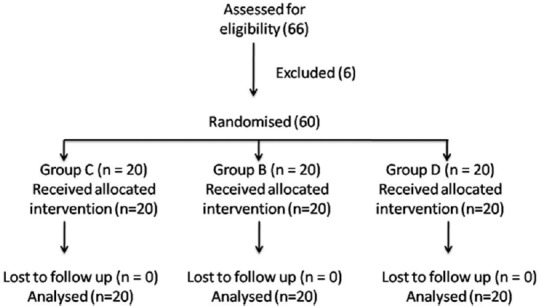

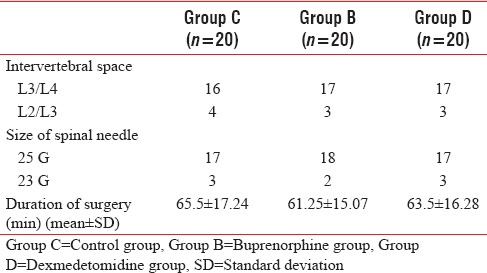

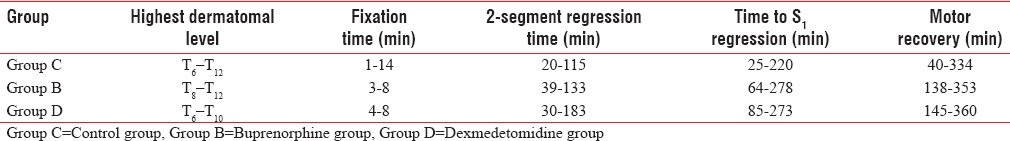

A total of 60 male patients were included in the study [Figure 1]. The demographic data were comparable between the groups with age range (mean) of 52–83 (65), 48–80 (66) and 52–78 (68) for groups C, B, and D, respectively. The intervertebral space and the size of spinal needle chosen for spinal anesthesia were comparable between the groups [Table 1]. The total duration of surgery was also comparable between the groups [Table 1]. Additional postoperative analgesia was not required in the first 24 h postoperatively in a total of 10 (50%), 12 (60%), and 15 (75%) patients in control, buprenorphine and dexmedetomidine groups, respectively. The time to first analgesic request in the remaining patients was 509 ± 199.8 min, 589 ± 158.3 min, and 429 ± 134 min in control, buprenorphine and dexmedetomidine groups, respectively. The other study variables are listed in Tables 2 and 3. The highest dermatomal level achieved after the performance of spinal anaesthesia (high dermatomal level), time taken for the spinal block to get fixed to the highest level (fixing time), time taken for the peak sensory level to recede by 2 segments (two-segment regression time), time for sensory regression to S1 dermatome (Time to S1 regression) and time taken for complete motor recovery (motor recovery) were recorded. All times were noted from the time of completion of injection of the spinal anesthetic drug.

Figure 1.

Consort flow chart for the study

Table 1.

Choice of intervertebral space, type of spinal needle and total duration of surgery

Table 2.

Range of study variables

Table 3.

Study variables (mean±standard deviation)

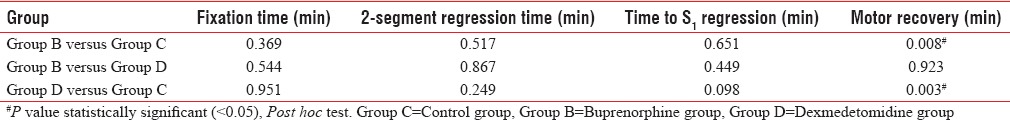

Table 2 reveals the range of the main study variables in minutes, whereas Table 3 reveals the mean and the standard deviation of the main study variables. Table 4 shows the values of statistical significance for individual study variables between groups. Eighteen patients in control group had RSS of 2, with 2 having an RSS of 1 requiring midazolam before administration of spinal anaesthesia. Seven patients in the buprenorphine group had an RSS of 3 at all times while the remaining 13 patients had an RSS of 2. All twenty patients in the dexmedetomidine group had an RSS of 3 at all times in the study period. None of the patients in any group had an RSS exceeding 4.

Table 4.

Statistical significance for study variables (intergroup comparison)

No patient in the control group had any perioperative complications such as hypotension, bradycardia, arterial desaturation, respiratory depression, nausea or vomiting. Six patients in the buprenorphine group had vomiting in the postoperative period and were treated with 0.1 mg/kg ondansetron intravenously. Two patients in dexmedetomidine group had transient hypotension following the injection of spinal anaesthesia needing a single bolus of IV mephentermine 3 mg to maintain blood pressure within 30% of the baseline. None of the patients had an SpO2 <90% or symptomatic bradycardia (HR <45 min−1).

DISCUSSION

Since the first clinical use of intrathecal morphine in 1979, several studies have shown the benefits of intrathecal opioids as adjuvants to local anesthetics in providing postoperative pain relief.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] However, redistribution by rostral spread following intrathecal administration results in several adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting and respiratory depression that become limiting factor in the use of intrathecal opioids.[18,19] Therefore, several spinal adjuvant drugs such as α2 agonists (clonidine or dexmedetomidine) have been studied as alternatives to intrathecal opioids.[13,20] However, even these drugs are not without adverse effects as more frequent episodes of arterial hypotension have been reported with their use without evidence of dose responsiveness.[21]

In this study, the sensorimotor effectiveness of the addition of buprenorphine (60 μg) or dexmedetomidine (5 μg) was compared to intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine (0.5%). Hyperbaric bupivacaine was chosen as the local anesthetic solution of choice as this is the only available local anesthetic for intrathecal administration in our institution. Moreover, many studies have confirmed the reliability and safety of hyperbaric bupivacaine as an intrathecal local anaesthetic agent. Buprenorphine dose of 60 μg was chosen as the safety of this dose in elderly patients is established.[14] Dexmedetomidine dose of 5 μg was chosen as this has been found to provide good, prolonged analgesia for other urological procedures.[15]

Additional postoperative analgesic was not required in the first 24 h in 10, 12, and 15 patients each in control, buprenorphine and dexmedetomidine groups, respectively. Intrathecal dexmedetomidine thus provided long-lasting analgesia with minimal adverse effects for patients undergoing TURP. No patient in this study had excessive sedation or respiratory depression which confirms that buprenorphine in a dose of 60 μg and dexmedetomidine in a dose of 5 μg are safe as intrathecal adjuvants to bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia in elderly patients.

In this study, it was also found that addition of either buprenorphine (60 μg) or dexmedetomidine (5 μg) to intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine (0.5%) resulted in prolongation of sensory block from 130 ± 46 to 144 ± 51.3 and 164 ± 55.99 min respectively though this was neither statistically nor clinically significant. A study of the motor block, however, revealed that motor recovery took 177 ± 56.9 min in the bupivacaine group as compared to 236 ± 60 and 234 ± 61.71 min in the buprenorphine and dexmedetomidine groups, respectively. This aspect is not an advantage for a procedure such as TURP though it might be useful in procedures such as herniorrhaphy or procedures in the lower limb where immobility in the intraoperative or immediate postoperative period would be an advantage.

Addition of only 30 μg buprenorphine to intrathecal bupivacaine has resulted in prolonged analgesia for 24 h in 6/20 patients who did not require any supplementary analgesia.[11] This finding is comparable with our study results where 8/20 patients did not require any supplementary postoperative analgesic in buprenorphine group in the 24 h study period. Addition of 60 μg buprenorphine has considerably prolonged the analgesia compared to bupivacaine alone which is comparable with our study results.[14] Addition of dexmedetomidine in doses of 5 μg or 10 μg to intrathecal bupivacaine has been found to prolong the sensory regression time to S1 as well as the time to complete motor recovery considerably. Although our study results are similar to the motor recovery findings of this study, our patients did not show significant prolongation of sensory regression to S1.[15]

Another study concluded that addition of a very minute dose of dexmedetomidine (3 μg) or clonidine (30 μg) to intrathecal bupivacaine produced similar prolongation in the duration of the motor and sensory block with preserved haemodynamic stability and lack of sedation.[13]

In women undergoing vaginal reconstructive surgery under spinal anaesthesia, 10 mg plain bupivacaine supplemented with 5 μg dexmedetomidine was found to prolong both motor and sensory blocks as compared to 25 μg fentanyl.[12] Although our study results correlate well with prolongation of the motor blockade with the addition of either buprenorphine or dexmedetomidine to intrathecal bupivacaine, prolongation of the sensory blockade with the addition of these drugs was not observed. The authors of other studies have used either pain or temperature to assess the dermatomal level and sensory regression while we used touch sensation to assess the level of sensory blockade.[11,12,13,14,15] This might be the reason for the differences in findings with reference to the sensory regression time.

Maharani et al. reported the prolonged duration of sensory and motor block with the addition of 10 mcg of dexmedetomidine to intrathecal bupivacaine when compared to the addition of 60 mcg of buprenorphine to intrathecal bupivacaine, which also had a significant increase in the incidence of nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression in patients undergoing infra-umbilical and lower limb surgeries. Consequently, the authors also reported a statistically significant increase in the first analgesic requirement time in the dexmedetomidine group compared to buprenorphine group.[22] We have used lower doses of both adjuvant drugs in our study with no incidence of respiratory depression in any of the patient groups. The justification for lower doses used in our study was that the nature of the patient group undergoing a lesser invasive nature of surgery compared to the patient group in the study by Maharani et al. We found a comparable prolongation of the duration of the first analgesic request in both drug groups.

Gupta et al. compared intrathecal dexmedetomidine and buprenorphine to bupivacaine in doses similar to that used in our study for lower abdominal surgeries. The authors reported Intrathecal dexmedetomidine when compared to intrathecal buprenorphine causes prolonged anaesthesia and analgesia with reduced need for sedation and rescue analgesics.[23]

Dexmedetomidine has been increasingly used as an adjuvant for spinal anaesthesia for supra and infraumbilical surgeries. Urological procedures constitute a fair majority of lower abdominal surgeries. Dexmedetomidine has been described as a useful adjuvant when used with bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia in urological procedures by resulting in a faster onset of sensory and motor block, improving quality of intraoperative and postoperative analgesia with good hemodynamic stability and minimal side effects.[24]

In another study comparing the effects of dexmedetomidine, buprenorphine and fentanyl as an adjuvant to bupivacaine during spinal anaesthesia for hip hemiarthroplasty, the authors concurred that addition of dexmedetomidine (5 μg) provides significantly longer duration of sensory and motor blockade and longer duration of first analgesic request in the recovery than intrathecal buprenorphine (30 μg) or Fentanyl 10 μg. Although the doses used in the study concur with ours, the results are varying. This could be because of a different patient population with a more invasive nature of surgery.[25]

Kim et al. studied the effects of low dose of Intrathecal dexmedetomidine (3 μg) with bupivacaine in comparison to intrathecal saline with bupivacaine in elderly patients undergoing TURP.[26] The authors also report a faster onset time to peak sensory motor effects and longer duration of motor and sensory blockade and longer duration of first analgesic request in the dexmedetomidine group, with the duration of analgesia lasting similar to the findings in our study. The authors do add that prolongation of the motor blockade may not be a desirable effect in these subsets of patients. We concur with the authors in this regard.

No study till date has compared the effects of buprenorphine and dexmedetomidine as adjuvants for spinal bupivacaine in patients undergoing Transurethral Prostatic Resection. Our study attempts to highlight the beneficiary effects of both drugs when used as adjuvants with acceptable side effect profile in this subset of patients.

Considering the sensory innervations to the prostate, a sensory block up to T11 is adequate for TURP. The prostate and bladder are innervated by both the sympathetic (pelvic plexus, hypogastric plexus) and parasympathetic (S3 and S4) autonomic divisions. The urethral sphincter should be adequately relaxed for the endoscope to pass freely, and the urethral sphincter is also supplied by the sympathetic division of the pelvic plexus (internal sphincter) and somatic fibres of the pudendal nerve (external sphincter). An understanding of the pain pathways for urinary bladder and the prostate would help understand the differences we have observed in our study. The pain sensations from both the urinary bladder and the prostate are mainly carried by sympathetic fibres (T11–L2) and not the somatic fibres.[1] Hence, it is possible to have reduction of analgesic requirements despite not having prolongation of sensory blockade to touch as has been the finding in our study.

The incidence of nausea and vomiting was higher with intrathecal buprenorphine which correlates with the findings of other studies.[11,14] Two patients who received intrathecal dexmedetomidine developed transient hypotension that was easily treated with mephentermine.

Our study has few limitations. We could have quantitatively measured the postoperative pain using scores such as visual analogue scale. We have used the sensory regression to S1 instead of S2 as pointer to recovery from sensory block as we felt that the patients may feel uncomfortable if repeated check for S2 level is done.

CONCLUSION

Addition of buprenorphine (60 μg) or dexmedetomidine (5 μg) to intrathecal bupivacaine for TURP in elderly male patients result in a comparable intraoperative and postoperative profile with prolongation of the time for first analgesic dose.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malhotra V. Transurethral resection of the prostate. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2000;18:883–97. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(05)70200-5. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirson LE, Goldman JM, Slover RB. Low-dose intrathecal morphine for postoperative pain control in patients undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:192–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198908000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nott MR, Jameson PM, Julious SA. Diazepam for relief of irrigation pain after transurethral resection of the prostate. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1997;14:197–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1997.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuusniemi KS, Pihlajamäki KK, Pitkänen MT, Helenius HY, Kirvelä OA. The use of bupivacaine and fentanyl for spinal anesthesia for urologic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1452–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200012000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarvela PJ, Halonen PM, Korttila KT. Comparison of 9 mg of intrathecal plain and hyperbaric bupivacaine both with fentanyl for cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tejwani GA, Rattan AK, McDonald JS. Role of spinal opioid receptors in the antinociceptive interactions between intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:726–34. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199205000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, Chakrabarti MK, Whitwam JG. Specific enhancement by fentanyl of the effects of intrathecal bupivacaine on nociceptive afferent but not on sympathetic efferent pathways in dogs. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:766–73. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199310000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abouleish E, Rawal N, Fallon K, Hernandez D. Combined intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine for cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1988;67:370–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abouleish E, Rawal N, Rashad MN. The addition of 0.2 mg subarachnoid morphine to hyperbaric bupivacaine for cesarean delivery: A prospective study of 856 cases. Reg Anesth. 1991;16:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boezaart AP, Eksteen JA, Spuy GV, Rossouw P, Knipe M. Intrathecal morphine. Double-blind evaluation of optimal dosage for analgesia after major lumbar spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:1131–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199906010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan FA, Hamdani GA. Comparison of intrathecal fentanyl and buprenorphine in urological surgery. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:277–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Ghanem SM, Massad IM, Al-Mustafa MM, Al-Zaben KR, Qudaisat IY, Qatawneh AM, et al. Effect of adding dexmedetomidine versus fentanyl to intrathecal bupivacaine on spinal block characteristics in gynecological procedures: A double blind controlled study. Am J Appl Sci. 2009;6:882–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanazi GE, Aouad MT, Jabbour-Khoury SI, Al Jazzar MD, Alameddine MM, Al-Yaman R, et al. Effect of low-dose dexmedetomidine or clonidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine spinal block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:222–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capogna G, Celleno D, Tagariello V, Loffreda-Mancinelli C. Intrathecal buprenorphine for postoperative analgesia in the elderly patient. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:128–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1988.tb05482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Mustafa MM, Abu-Halaweh SA, Aloweidi AS, Murshidi MM, Ammari BA, Awwad ZM, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine added to spinal bupivacaine for urological procedures. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kararmaz A, Kaya S, Turhanoglu S, Ozyilmaz MA. Low-dose bupivacaine-fentanyl spinal anaesthesia for transurethral prostatectomy. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:526–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham AJ, McKenna JA, Skene DS. Single injection spinal anaesthesia with amethocaine and morphine for transurethral prostatectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:423–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/55.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy PM, Stack D, Kinirons B, Laffey JG. Optimizing the dose of intrathecal morphine in older patients undergoing hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1709–15. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000089965.75585.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pirat A, Tuncay SF, Torgay A, Candan S, Arslan G. Ondansetron, orally disintegrating tablets versus intravenous injection for prevention of intrathecal morphine-induced nausea, vomiting, and pruritus in young males. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1330–6. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180830.12355.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Axelsson K, Gupta A. Local anaesthetic adjuvants: Neuraxial versus peripheral nerve block. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:649–54. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32832ee847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elia N, Culebras X, Mazza C, Schiffer E, Tramèr MR. Clonidine as an adjuvant to intrathecal local anesthetics for surgery: Systematic review of randomized trials. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:159–67. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maharani B, Sathya Prakash M, Kalaiah P, Elango NC. Dexmedetomidine and buprenorphine as adjuvant to spinal anesthesia – A comparitive study. Int J Curr Res Rev. 2013;5:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta M, Shailaja S, Hegde KS. Comparison of intrathecal dexmedetomidine with buprenorphine as adjuvant to bupivacaine in spinal asnaesthesia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:114–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7883.4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akhter M, Mir AW, Ahmad B, Ahmad F, Sidiq S, Shah MA, et al. Dexmedetomidine as an adjunct to spinal anesthesia in urological procedures. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2017;4:154–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pradeep R, Thomas J. Comparison of dexmedetomidine, buprenorphine and fentanyl as an adjunct to bupivacaine spinal anaesthesia for hemiarthroplasty. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2016;3:4474–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JE, Kim NY, Lee HS, Kil HK. Effects of intrathecal dexmedetomidine on low-dose bupivacaine spinal anesthesia in elderly patients undergoing transurethral prostatectomy. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36:959–65. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-01067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]