Abstract

Background & objectives:

Several outbreaks of acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) have been reported in Alappuzha district, Kerala State, India, in the past. The aetiology of these outbreaks was either inconclusive or concluded as probable Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection based on clinical presentation. The role of West Nile virus (WNV) in AES outbreaks was also determined. However, the extent of WNV infection has not been studied in this region previously. A population-based cross-sectional serosurvey study was undertaken to determine the seroprevalence of JEV and WNV in Alappuzha district.

Methods:

A total of 30 clusters were identified from 12 blocks and five municipalities as per the probability proportional to size sampling method. A total of 1125 samples were collected from all age groups. A microneutralization assay was performed to estimate the prevalence of JEV and WNV neutralizing antibodies in the sample population.

Results:

Of 1125 serum samples tested, 235 [21.5%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 15.2-27.8%] and 179 (15.9%, 95% CI: 9.6-22.3%) were positive for neutralizing antibodies against WNV and JEV, respectively. In addition, 411 (34.5%, 95% CI: 26.7-42.2%) were positive for cross-reactive antibodies against flaviviruses.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study showed the seroprevalence of WNV and JEV antibodies in the surveyed area and the WNV seroprevalence was greater than JEV. It is necessary to create awareness in public and adopt suitable policy to control these diseases.

Keywords: Alappuzha, flaviviruses, Japanese encephalitis virus, Kerala, serosurvey, West Nile virus

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and West Nile virus (WNV) belong to the Japanese encephalitis (JE) antigenic complex of viruses within the family Flaviviridae that are a cause of viral encephalitis in humans. These viruses cause asymptomatic infection in the majority of the infected humans. Most infections with JEV are subclinical1, with a ratio of symptomatic to asymptomatic infections estimated to be 1:25-1:10002,3. Most of the clinical studies related to WNV emphasize WN encephalitis and WN (WN) meningitis. However, the studies from the United States and Romania revealed that meningitis or encephalitis occurred in only about one of 150 infected persons4. Both the viruses are transmitted mainly by Culex sp. in different parts of India5. JE is a major public health problem in the Asian sub-continent, accounting for more than 16,000 reported cases and 5000 deaths annually6. Over three billion individuals live in JE epidemic and/or endemic countries. It is estimated that approximately 67,900 JE cases have occurred annually in 24 countries, with only 10,426 cases reported in 20117,8. The fatality rate in JE clinical cases ranges from 20 to 30 per cent, with neurologic or psychiatric sequelae observed in 30-50 per cent of survivors. In India, many encephalitis outbreaks have been associated with JEV9. Swine and ardeid birds are major amplifying hosts for JEV.

WNV causes fever and neuroinvasive disease. Birds are the natural reservoir of the virus. The virus is maintained in nature by a mosquito–bird–mosquito transmission cycle. Mammals serve primarily as dead-end hosts because their transient viraemia is inadequate to infect Culex mosquitoes. WNV is now endemic globally; however, most previous epidemics occurred mainly in rural populations, with a few cases of severe neurological disease10. In India, antibodies against WNV were first detected in human serum samples from Bombay in 195211 and subsequently in South Arcot district of Tamil Nadu12. Fatal cases with WNV infection were reported in children unlike in older age groups in other countries13.

The first reported acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) outbreak in Kerala, India, occurred in Kuttanad region between January and February 1996, causing 105 cases and 31 deaths14. Although JEV was reported to be an aetiological agent associated with the outbreak, there were some exceptional features noticed during the outbreak. The seasonality of the outbreak was different from the one known for JE in Kerala. Most of the patients were from the adult age groups, whereas JE occurs mainly in children15. Another outbreak occurred in 1997 causing 121 cases and 19 deaths14. The role of WNV in AES cases was not ruled out during the reported outbreaks, and thereafter, no major AES outbreaks were reported. We have reported an AES outbreak during May through July 2011 in Kerala, India16. The patients had a high fever with headache and one or more neurological deficits, including altered sensorium, disorientation, irritability, neck rigidity and vomiting. WNV was isolated from the serum of a patient with acute fever and serological assays confirmed WNV as the aetiology in this outbreak. Further, WNV genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis confirmed that the virus belonged to lineage 1 of WNV17.

Prevalence of JEV and WNV infections in Alappuzha district is unknown. The prevalence of antibodies against JEV and WNV has not previously been investigated in this region. It has become necessary to understand the extent of the infection to plan and implement the intervention measures. Whereas a licensed vaccine exists for JEV, none are available for WNV, making the determination of aetiology critical for decision support. Since there were no data regarding the population exposure to WNV and other flaviviruses, it was thus essential to have baseline information on seroprevalence of these viruses in the region. Therefore, a cross-sectional serosurvey was conducted to estimate the seroprevalence of these infections in Alappuzha district, Kerala. Samples were taken from 1135 individuals, including all age groups from different areas to acquire a cross-section of the Alappuzha district population.

Material & Methods

A population-based, cross-sectional serosurvey was carried out after the last reported case of WNE in Alappuzha district during September-October 2012. The survey was completed within a month. The serosurvey was conducted in Alappuzha, also known as Alleppey, a district in the state of Kerala, India. This region of India is surrounded by the coast of Arabian Sea on the west and by the Western Ghats in the east and has a population of 2.122 million. The district is divided into 12 blocks and five municipalities. A total of 30 clusters were identified from 12 blocks and 5 municipalities as per the probability proportional to size sampling method. The sample size was calculated based on the assumption of 50 per cent seroprevalence with precision of 5 per cent, design effect = 3, number of clusters = 30. Using CSurvey 2.0 (UCLA free software for cluster survey), the calculated sample size was 1157 and it was rounded to 1200. The total number of samples was divided by 30 (clusters), and the calculated sample size per cluster was 40. All the villages/wards within the selected panchayat/municipality were enlisted and serially numbered. A random number was generated and was considered for the selection of first sampling village/locality. The subjects were covered in equal or proportionate age groups.

Demographic data collected from the participants included age, sex, education level, occupation, income and comorbidities. Blood (3-5 ml) was collected in vacutainers and transported to the National Institute of Virology (NIV), Kerala Unit, Alappuzha, in cold chain at 2-8°C. Serum was separated and stored in at least three aliquots at −20°C.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of NIV, Pune and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Antibody detection: Exposure to JEV and WNV was confirmed by estimating the presence of antibody by a virus microneutralization assay18. The assay was done in porcine stable (PS) kidney cells (NCCS, Pune) using virus isolates JEV (733913) and WNV (G22886) by observing the cytopathic effect in a 96-well tissue culture plate (Corning Life sciences, USA). The standard virus isolates were obtained from Virus Repository, National Institute of Virology, Pune. Mouse polyclonal anti-JEV and -WNV antibodies (positive controls) along with a non-immune serum (negative control) were included in each assay. The polyclonal antibodies were obtained from encephalitis group, National Institute of Virology, Pune.

Micro-virus neutralization assay: Neutralization assay was performed as described by Sapkal et al18. Briefly, PS kidney cell-adapted virus was used in this assay. Two-fold serially diluted sera were incubated with two log tissue culture infective dose, 50 per cent (TCID50) of the test virus for an hour at 37°C. The test virus- antibody mixture was added to a pre-formed monolayer of PS kidney cells in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C with 5 per cent CO2 for 72 h. Ten-fold dilution of virus without antibody (virus control), mouse polyclonal anti-JEV and -WNV serum (positive control) with two log TCID50 of respective virus and normal non-immune serum (negative control) was added in respective wells as a control in this assay. Neutralizing titre was expressed as the reciprocal of the serum dilution at which 50 per cent of virus added was neutralized. The initial dilution used in this assay was 1:5 and the last dilution used was 1:320. A sample having a titre of ≥1:20 was considered positive. JEV and WNV were identified specifically by a four-fold difference in titre. The samples showing titre above twenty and equal for both JEV and WNV were considered to be equivocal.

Statistical analysis: The participants were first stratified according to their age, sex and area of domicile. Thereafter, they were divided into the following age groups of <15, 15-44, 45-64 and 65 yr and above for comparison and statistical analysis. The area of domicile was divided into two strata, urban and rural based on population density. The sample weight was calculated as described by Bennett et al19. Analysis was carried out using complex sample module as implemented in Epi-info version 7 (CDC, USA)

Results

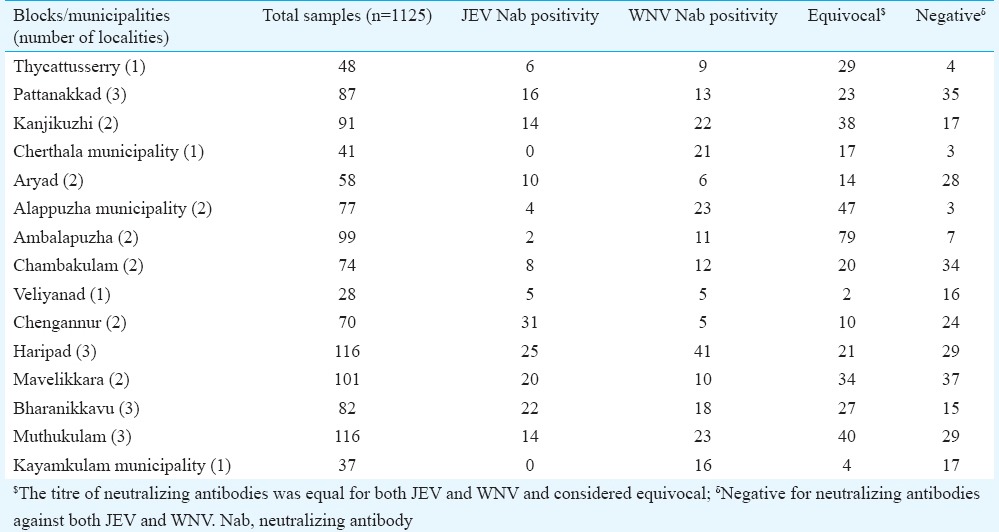

A total of 1135 samples were collected from all the clusters. The testing could not be performed on 10 samples either due to insufficient amount or contamination. The results of 1125 samples were considered for further analysis. Block/municipality samples collected and seropositivity based on their Neutralization titres (NT) for JEV and WNV are given in the Table I.

Table I.

Block/municipality-wise Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and West Nile virus (WNV) neutralizing antibodies positivity in Alappuzha district

Of 1125 samples tested, 235 [21.5%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 15.2-27.8%] and 179 (15.9%, 95% CI: 9.6-22.3%) were confirmed positive for WNV and JEV, respectively. Equivocal results were observed in 411 (34.5%, 95% CI: 26.7-42.2%) samples and 300 (28.1%, 95% CI: 21-35%) samples were negative for both JEV and WNV. Of the non-specific Flavivirus neutralizing antibodies, JEV and WNV neutralization titres of 1:20 were recorded for 27 per cent and 22 per cent of the equivocal samples, respectively.

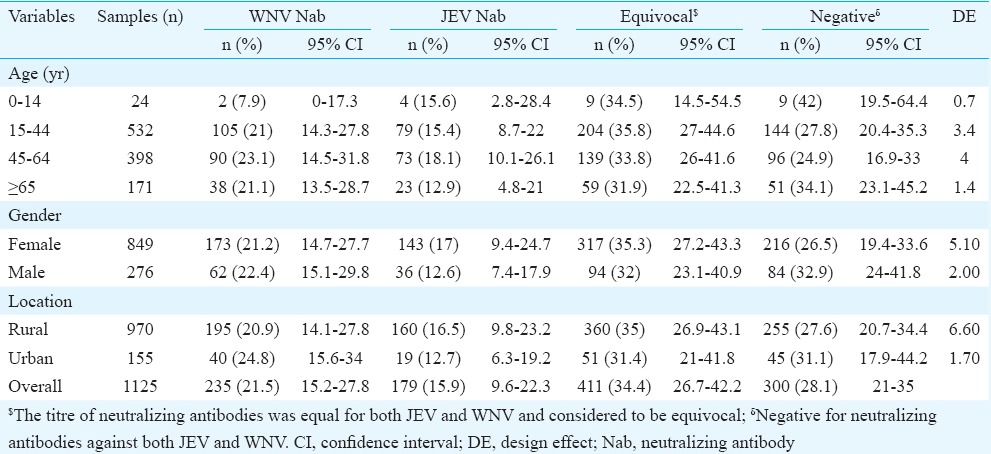

Age, sex and rural and urban distribution of JEV and WNV positives are given in Table II. No significant difference was noticed in percentage positivity in different age groups for both JEV and WNV. The percentage positivity of neutralizing antibodies against WNV was higher than the percentage positivity of neutralizing antibodies against JEV in all age groups analyzed in this study, except for the 0-14 yr age group. Of 1125 samples collected, 155 samples were from urban settings and 970 were from rural settings.

Table II.

Seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies against Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and West Nile virus (WNV) in Alappuzha district

Discussion

A WNE outbreak leading to three deaths occurred in this region7, but not a single case was reported from the known JE endemic areas. As both JEV and WNV share same ecological conditions, seasonality and vectors, it became very difficult to categorize the introduction of WNV into the JE endemic area. Since there was no documentation of the risk of JE and other flaviviruses, in this study region, before this outbreak, it was thus necessary to have baseline information on the seroprevalence of these viruses in the region. Owing to the high number of cases in the non-endemic region, it has become necessary to understand the extent of the infection in the area to plan and implement the control measures.

Our study result indicated that the overall seroprevalence of JE and WNV in Alappuzha district population was 37 per cent without including equivocal results. In other endemic areas such as Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, serological responses studied using haemagglutination inhibition and neutralization test have indicated that the seroprevalence of both JEV and WNV antibodies was nearly 50 per cent in the adult population11.

Our study showed the presence of both JEV and WNV activity in the Kerala region, India. The human serological survey indicated an active focus of Flavivirus infection in Kerala, probably linked to the first invasion of the archipelago by WNV. Detection of JEV and WNV IgM antibodies in humans during 2011 indicated that Flavivirus infections probably occurred during this period and the infection might spread in the population16. We have thus resorted to increasing surveillance activity, collection and storing of appropriate samples from AES cases and serological survey in the affected areas to detect the new introduction of WNV into Kerala region of India.

Our study had some limitations. The low number of the samples from the children below the age of 14 yr old was one of the main limitations. JE vaccination has been practiced in Alappuzha district since 2008. Children are vaccinated at 18 and 36 months. As per the Directorate of Health Services, Kerala, the vaccine coverage is approximately 60 per cent (personal communication). Therefore, to identify the population with immunity following natural infection, vaccinated children were excluded from the study. In addition, many children were not available during the sampling period. They were either in school or the parents refused to provide consent to draw blood samples. Participation of the low number of male subjects in this study was another limitation. The skewed male and female ratio (1:3) was due to the non-availability of adult male members during sample collection. The serological survey was done during weekdays and most of the male adult members were away for work.

The microneutralization assay employed here could not differentiate Flavivirus cross-reacting antibodies that neutralize both JEV, WNV and to some extent dengue virus. Serological cross-reactivity among flaviviruses has been well documented20. In this study, approximately 35 per cent of the samples showed equivocal results which interfered with estimation of the true seroprevalence of JEV and WNV. WNV-specific IgG ELISA (West Nile Detect™ IgG ELISA, InBios International, USA) was done on some selected samples which included equivocal-, WNV- and JEV-positive samples. The assay is specific to WNV IgG and confirmed that JEV NT-positive samples were negative for WNV IgG. Interestingly, the equivocal samples were positive for WNV IgG, confirming cross-reactivity between JEV and WNV. Therefore, if we consider the equivocal sample as JEV and WNV reactive, the overall seroprevalence would increase to 72 per cent. This was a very high seropositivity for this region.

In conclusion, this study showed that human infection with JE and WN viruses was common in this area and that the overall seroprevalence to both these viruses was 37 per cent and possibly as high as 72 per cent if unidentified Flavivirus antibodies were included. Although these viruses cause neurological disease in a very low percentage of exposed individuals, special attention needs to be given to people with pre-existing comorbid conditions and the elderly people. Public awareness should be created and suitable policies adopted to control mosquito vectors.

Acknowledgment

The project was supported through in-house grant. Authors acknowledge Director, NIV, for his support, and all health inspectors, junior health inspectors, Accredited Social Health activists, District Medical Officer and doctors from peripheral hospitals, Alappuzha district, and technicians from the NIV, Kerala, and NIV, Pune, who helped during the field study. Authors thank Shri Santosh M. Jadhav for statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Shope RE. Other flavivirus infections. In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, editors. Tropical Infectious diseases: Principles, pathogens, and practice. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. pp. 1275–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon T, Dung NM, Kneen R, Gainsborough M, Vaughn DW, Khanh VT. Japanese encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:405–15. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benenson MW, Top FH, Jr, Gresso W, Ames CW, Altstatt LB. The virulence to man of Japanese encephalitis virus in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1975;24(6 Pt 1):974–80. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. West Nile virus. [accessed on August 20 2016]. Available from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs354/en/

- 5.National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, India. Japanese Encephalitis Vectors in India. [accessed on March 16 2016]. Available from http://www.nvbdcp.gov.in/je4.html .

- 6.Halstead SB, Jacobson J. Japanese encephalitis. Adv Virus Res. 2003;61:103–38. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)61003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Japanese encephalitis surveillance and immunization –Asia and the Western Pacific 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:658–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell GL, Hills SL, Fischer M, Jacobson JA, Hoke CH, Hombach JM, et al. Estimated global incidence of Japanese encephalitis: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:766–74. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.085233. 774A-E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodrigues FM. Proceedings of the national conference on Japanese encephalitis. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1984. Epidemiology of Japanese Encephalitis in India: A brief overview; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gyure KA. West Nile virus infections. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:1053–60. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181b88114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banker DD. Preliminary observations on antibody patterns against certain viruses among inhabitants of Bombay city. Indian J Med Sci. 1952;6:733–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risbud AR, Sharma V, Rao CV, Rodrigues FM, Shaikh BH, Pinto BD, et al. Post-epidemic serological survey for JE virus antibodies in South Arcot district (Tamil Nadu) Indian J Med Res. 1991;93:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajanana A, Thenmozhi V, Samuel PP, Reuben R. A community-based study of subclinical flavivirus infections in children in an area of Tamil Nadu, India, where Japanese encephalitis is endemic. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:237–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabilan L, Rajendran R, Arunachalam N, Ramesh S, Srinivasan S, Samuel PP, et al. Japanese encephalitis in India: An overview. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:609–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02724120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S. Japanese encephalitis outbreak in Kerala has unusual features. Lancet. 1996;347:678. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anukumar B, Sapkal GN, Tandale BV, Balasubramanian R, Gangale D. West Nile encephalitis outbreak in Kerala, India 2011. J Clin Virol. 2014;61:152–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balakrishnan A, Butte DK, Jadhav SM. Complete genome sequence of West Nile virus isolated from Alappuzha district, Kerala, India. Genome Announc. 2013;1(pii):e00230–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00230-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapkal GN, Wairagkar NS, Ayachit VM, Bondre VP, Gore MM. Detection and isolation of Japanese encephalitis virus from blood clots collected during the acute phase of infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:1139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett S, Woods T, Liyanage WM, Smith DL. A simplified general method for cluster-sample surveys of health in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1991;44:98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calisher CH, Karabatsos N, Dalrymple JM, Shope RE, Porterfield JS, Westaway EG, et al. Antigenic relationships between flaviviruses as determined by cross-neutralization tests with polyclonal antisera. J Gen Virol. 1989;70(Pt 1):37–43. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]