Abstract

Background: Information technology, including clinical decision support systems (CDSS), have an increasingly important and growing role in identifying opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship–related interventions. Objective: The aim of this study was to describe and compare types and outcomes of CDSS-built antimicrobial stewardship alerts. Methods: Fifteen alerts were evaluated in the initial antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) review. Preimplementation, alerts were reviewed retrospectively. Postimplementation, alerts were reviewed in real-time. Data collection included total number of actionable alerts, recommendation acceptance rates, and time spent on each alert. Time to de-escalation to narrower spectrum agents was collected. Results: In total, 749 alerts were evaluated. Overall, 306 (41%) alerts were actionable (173 preimplementation, 133 postimplementation). Rates of actionable alerts were similar for custom-built and prebuilt alert types (39% [53 of 135] vs 41% [253 of 614], P = .68]. In the postimplementation group, an intervention was attempted in 97% of actionable alerts and 70% of interventions were accepted. The median time spent per alert was 7 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 5-13 minutes; 15 [12-17] minutes for actionable alerts vs 6 [5-7] minutes for nonactionable alerts, P < .001). In cases where the antimicrobial was eventually de-escalated, the median time to de-escalation was 28.8 hours (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.0-69.1 hours) preimplementation vs 4.7 hours (95% CI, 2.4-22.1 hours) postimplementation, P < .001. Conclusions: CDSS have played an important role in ASPs to help identify opportunities to optimize antimicrobial use through prebuilt and custom-built alerts. As ASP roles continue to expand, focusing time on customizing institution specific alerts will be of vital importance to help redistribute time needed to manage other ASP tasks and opportunities.

Keywords: antimicrobial stewardship, clinical decision support systems, infectious diseases

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance threatens the treatment of once manageable infections with over 2 million illnesses and 23 000 deaths annually attributed to organisms resistant to currently available antimicrobials in the United States.1-3 National organizations, including Infectious Diseases Society of America, have advocated and provided guidance for establishing antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) to help alleviate the increasing risk of emerging resistant microorganisms and to optimize the use of currently available antimicrobials. One of the core interventions of ASPs to assist with reducing inappropriate use of antimicrobials includes prospectively auditing and intervening on antimicrobial use, and then providing feedback and recommendations to medical team members.1

Health care information technology has had an increasingly growing and important role in the identification of ASP-related tasks and interventions. Electronic health records (EHR) and clinical decision support systems (CDSS), such as TheraDocTM (Salt Lake City, Utah), provide real-time alerts updated when new microbial culture results become available or antimicrobial changes occur. These systems help ASPs by providing a means to track resistant pathogens, antimicrobial utilization, data on patient-specific microbiology cultures and susceptibilities, patient-specific factors (eg, hepatic and renal function), adverse drug reactions, and drug-drug interactions. CDSS have both prebuilt and customizable antimicrobial stewardship–related alerts which can be created for specific patient care units or for an entire institution.1,4,5

Prior studies assessing the impact of CDSS on ASPs have demonstrated process and economic measure benefits of these technologies by reducing the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, improving antibiotic dosing, and optimizing the selection of antibiotics. In addition, one study noted an increased number of intervention rates following implementation of CDSS.1,6 Of note, CDSS reduced the workload of ASP team members by 1 hour per day and resulted in cost savings of upward of $84 000 over a 3-month study period.7 Notably, only 24% to 36% of alerts have been deemed actionable in previous studies.6,8 As the expectations and tasks undertaken by ASPs continue to increase, the time and efforts allotted for specific tasks (eg, reviewing and intervening on alerts) will have to be managed accordingly. Of note, there is currently a paucity of data guiding clinicians on the types of stewardship alerts that are likely to lead to actionable interventions and the time that is spent reviewing and intervening on specific types of alerts. Therefore, we sought to characterize and evaluate actionable ASP alerts built in a CDSS as part of an established ASP at a large academic medical center. The primary objective of our study was to evaluate the types and percentage of actionable alerts. Secondary outcomes included acceptance rates of stewardship-related recommendations, time to de-escalation of antimicrobials, time to appropriate therapy if escalation was needed, and the time involved assessing and intervening on stewardship interventions.

Methods

This pilot study was conducted at Cleveland Clinic, part of the Cleveland Clinic Health-System, a 1400-bed tertiary care academic medical center. Adult patients (≥18 years or older) were included in the study if generation of one of 15 prebuilt or custom-built stewardship alerts (Table 1) occurred from the CDSS (TheraDocTM). This was a quasi-experimental preintervention and postintervention study, with the intervention referring to the implementation of a CDSS. During the 1-month preimplementation period (March 1-31, 2014), there was not a consistent method for identifying patients with ASP-related intervention opportunities or for conducting prospective intervention and feedback for named interventions. During the 1-month postimplementation period (May 19-June 20, 2014), 15 antimicrobial stewardship alerts were evaluated in real-time by ID clinical pharmacy specialists or postgraduate year 2 pharmacy residents. These evaluations occurred during the work weekdays (Monday through Friday), and interventions were acted upon by contacting clinicians after reviewing the available data in CDSS and EHR. Along with ASP alert evaluations, pharmacists were involved in patient care rounds, pharmacokinetics dosing services, and teaching. In the preimplementation phase, patients were identified retrospectively for inclusion using the electronic medical record and the same criteria used to trigger alerts in the postimplementation phase. Included patients and related intervention opportunities were retrospectively reviewed by an infectious diseases (ID) clinical pharmacy specialist.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial Stewardship Alerts Built in CDSS.

| Alert category and name | Type of alert |

|---|---|

| Therapeutic Antibiotic Monitoring (TAM) | |

| TAM Susceptibility known, inpatient (therapy de-escalation and escalation)a | Prebuilt |

| De-escalation Alert | |

| Vancomycin- and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus | Custom-built |

| Daptomycin/linezolid and ampicillin/vancomycin susceptible Enterococcus | Custom-built |

| Micafungin and non–Candida glabrata | Custom-built |

| Escalation Alert | |

| Fluconazole and C glabrata | Custom-built |

| Micafungin and Cryptococcus spp. | Custom-built |

| TAM susceptibility known, inpatient | Custom-built |

| Drug interaction | |

| Ciprofloxacin and contraindicated drug interaction | Custom-built |

| Itraconazole or posaconazole and proton-pump inhibitor | Custom-built |

| Itraconazole and contraindicated drug interaction | Custom-built |

| Protease inhibitors and statins | Custom-built |

| Rifampin and contraindicated drug interaction | Custom-built |

| Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and contraindicated drug interaction | Custom-built |

| Voriconazole and contraindicated drug interaction | Custom-built |

| ADR monitoring/avoidance | |

| Daptomycin and elevated CPK | Custom-built |

| Daptomycin and no CPK within 7 days of therapy | Custom-built |

Note. CDSS = clinical decision support systems; ADR = adverse drug reaction; CPK = creatine phosphokinase.

TAM susceptibility known alerts occur when susceptibility of an organism is available and marks an opportunity to de-escalate or escalate therapy based on cultures and susceptibility.

For each included patient, the total number of actionable alerts, number of attempted interventions (post–CDSS implementation), and percentage of accepted interventions were recorded. In addition, the reason for nonactionable items and time spent on each type of alert was documented.

Actionable alerts were defined as an intervention that was or could have been attempted based on clinical features as deemed appropriate by the pharmacist. Intervention time was the time a pharmacist spent evaluating alerts in the CDSS, reviewing the EHR, and intervening on alerts, if deemed necessary. Time to de-escalation of therapy was the opportunity time once the alert signaled in the CDSS to time the broad-spectrum antimicrobial was stopped. Time to appropriate therapy was the time from culture draw to time at which targeted antimicrobial therapy was initiated or escalated based upon in vitro susceptibility data.

Categorical variables are reported as n (%) and were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables are reported as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test as the data were not normally distributed. Survival analysis was utilized to evaluate the times to escalation and de-escalation. Median and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and survival distributions were analyzed with the log-rank test. All tests were 2-tailed, and a P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS, version 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

A total of 572 patient cases were included (304 preimplementation and 268 postimplementation), and 774 alerts were reviewed in the study. Of these, 25 alerts in pediatric patients were excluded for a total of 749 included alerts in the final evaluation—373 and 376 alerts in the preimplementation and postimplementation groups, respectively. A summary of baseline characteristics of the study patient population is outlined in Table 2. The primary service was most frequently medical (52% vs 57%), and there was an infectious diseases consult for 48% and 47% of alerts in the preimplementation and postimplementation groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients in Study Population.

| Variable | Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 62 (53-72) | 61 (47-70.8) | .018 |

| Male, n (%) | 194 (52.0) | 197 (52.4) | .942 |

| Hospital LOS, d, median (IQR) | 12 (6.5-26.5) | 12 (6-24.8) | .879 |

| Primary service, medical, n (%) | 195 (52.3) | 214 (56.9) | .213 |

| Primary service, surgical, n (%) | 178 (47.7) | 162 (43.1) | |

| Infectious diseases consultation, n (%) | 177 (47.5) | 178 (47.3) | 1 |

Note. IQR = interquartile range; LOS = length of stay.

Summary of alert outcomes is presented in Table 3. The most common alert types were prebuilt de-escalation and escalation (ie, bug-drug mismatch) Therapeutic Antibiotic Monitoring (TAM) alerts (614 of 749, 82%), custom-built de-escalation alerts (63 of 749, 8%), and custom-built drug interaction alerts (54 of 749, 7%). Custom-built therapy escalation and adverse drug reaction monitoring resulted in the least number of alerts. Overall, 306 (41%) of alerts were deemed actionable (173 [46.4%] preimplementation and 133 [35.4%] postimplementation, P = .002). There was no difference in the percentage of actionable interventions between custom-built (53 of 135, 39%) and prebuilt alerts (253 of 614, 41%, P = .68). In the postimplementation group, an intervention was attempted in 97% of alerts that were deemed actionable, with a 70% acceptance rate. The majority of these interventions were discussed with physician residents and infectious diseases–attending physicians and fellows-in-training. Reasons for alert nonacceptance included provider discretion to maintain course of therapy based on additional patient information, patient status change to comfort care, a pending ID consult, and no return call from provider.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial Stewardship–Related Alert Summary.a

| Alert category and name | Preimplementation (n = 373) | Postimplementation (n = 376) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAM alerts | 324 (86.9) | 290 (77.1) | .001 |

| Actionable | 151 (46.6) | 102 (35.2) | .005 |

| De-escalation | 84 (55.6) | 46 (45.1) | .124 |

| Escalation | 67 (44.4) | 56 (54.9) | |

| Intervention attempted | NA | 100 (98) | |

| Intervention accepted | NA | 72 (72) | |

| De-escalation alerts | 16 (4.3) | 47 (12.3) | <.001 |

| Actionable | 4 (25) | 15 (31.9) | .757 |

| Intervention attempted | NA | 14 (93.3) | |

| Intervention accepted | NA | 10 (71.4) | |

| Escalation | 6 (1.6) | 6 (1.6) | 1 |

| Actionable | 3 (50) | 1 (16.7) | .545 |

| Intervention attempted | NA | 1 (100) | |

| Intervention accepted | NA | 1 (100) | |

| Drug interaction | 23 (6.2) | 31 (8.2) | .323 |

| Actionable | 13 (56.5) | 13 (41.9) | .409 |

| Intervention attempted | NA | 12 (92.3) | |

| Intervention accepted | NA | 6 (50) | |

| ADR monitoring/avoidance | 4 (1.1) | 2 (0.5) | .450 |

| Actionable | 2 (50) | 2 (100) | .467 |

| Intervention attempted | NA | 2 (100) | |

| Intervention accepted | NA | 2 (100) | |

| Total | 373 | 376 | |

| Actionable | 173 (46.4) | 133 (35.4) | .002 |

| Intervention attempted | NA | 131 (97) | |

| Intervention accepted | NA | 91 (69.5) |

Note. TAM = Therapeutic Antibiotic Monitoring; NA= not applicable; ADR = adverse drug reaction.

Data presented as n (%).

Reasons for nonactionable alerts are presented in Table 4. The most common reason for nonactionable alerts in both the preimplementation and postimplementation groups included no need for intervention or therapy deemed appropriate at the time of review (ie, antimicrobial therapy appropriate based on additional available cultures; 87% vs 72.4% in the preimplementation and postimplementation groups, respectively).

Table 4.

Reason for Nonactionable Alerts.a

| Reason | Preimplementation (n = 200) | Postimplementation (n = 243) |

|---|---|---|

| Therapy deemed appropriate/no need for intervention | 173 (86.5) | 176 (72.4) |

| Alerts based on old data | 9 (4.5) | 23 (9.5) |

| Duplicate alert | 10 (5.0) | 20 (8.2) |

| Error | 4 (2.0) | 8 (3.3) |

| Patient-made comfort care | 4 (2.0) | 8 (3.3) |

| Intervention already made by infectious diseases or pharmacist | 0 | 8 (3.3) |

Note. Overall P = .004 (Fisher’s exact test).

Data presented as n (%).

In the postimplementation phase, pharmacists tracked time spent reviewing and intervening on alerts. The median (IQR) time spent on each alert was 7 (5-13) minutes. More time was spent on each actionable alert compared with each individual nonactionable alert (median [IQR]: 15 [12-17] vs 6 [5-7] minutes, respectively, P < .001).

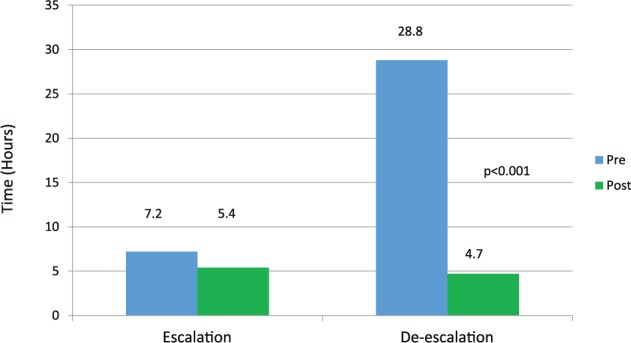

Clinical outcomes related to ASP alerts were also evaluated. The median (95% CI) time to de-escalation in those antimicrobials that were eventually de-escalated was 28.8 (10.0-69.1) hours in the preimplementation group compared with 4.7 (2.4-22.1) hours in the postimplementation group (P < .001; Figure 1). In addition, time to escalation to appropriate therapy was significantly shorter in the postimplementation group, 5.4 (3.4-7.0) hours, when compared with the preimplementation group 7.2 (6.1-9.4) hours (P = .016; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time to escalation or de-escalation of therapy.

Discussion

CDSS are designed to help ASPs identify opportunities for optimization of antimicrobial use and courses of therapy; however, little has been presented studying the value of different types of CDSS alerts. We attempted to evaluate the value of a CDSS for our ASP combining the number of alerts generated, the percentage of actionable alerts, the time spent evaluating alerts, and the impact on clinical outcomes.

CDSS usually offer both prebuilt (manufacturer-based) alerts and the capability of building alerts that are institution specific (custom-built). Prebuilt alerts are readily available, often robust, but sometimes have limited customization capabilities. Custom-built alerts require time to build and test to ensure accuracy, but these alerts allow tailoring to institutional needs.

Similar to prior studies, the most common alerts in our study were both prebuilt and custom-built alerts aimed at therapy escalation and de-escalation.6 The rate of alerts that were actionable were similar between prebuilt and custom-built alerts. The high rate of nonactionable alerts was due to therapy being deemed appropriate either because the opportunity was already acted upon or based on available information an intervention was not needed. Despite the low actionable rate of alerts, the clinical impact of these alerts can still be meaningful as demonstrated by the significantly shorter time to initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy in the postimplementation group.

While our EHR performs extensive drug-drug interaction screenings, these alerts may be overlooked due to alert fatigue or inappropriately evaluated by prescribers or pharmacists. Customized drug interaction alerts decrease the risk of inadvertent adverse reactions and subtherapeutic concentrations of targeted antimicrobials. The number of drug interaction alerts captured and intervened on in the current study highlights the value of this component of a CDSS. Furthermore, the current state of many EHRs does not allow for linking and capturing adverse drug reactions related to specific drugs (eg, creatine phosphokinase elevations and daptomycin use). While the number of adverse drug alerts in the current study was relatively low, these alerts were associated with high actionable intervention and acceptance rates and may provide a significant impact on therapy-related patient outcomes. Similarly, although the number of custom-built therapy escalation alerts was relatively low, the availability and overall impact of such alerts can prove to be essential in helping to recognize cases where optimal coverage against microorganisms is needed. This will assist with decreasing the risk of emerging antimicrobial resistant pathogens and potential toxicity from exposure to inappropriate antimicrobial therapies.

Based on the median time spent on each alert type during the current study and the overall reported number of actionable alerts from current and previous reports, if over 70% of alerts are noted to be nonactionable, the majority of pharmacists’ time would be spent evaluating these specific alerts. While building alerts that are actionable in nature helps redistribute an ASP provider’s time to complete other ASP-related tasks and interventions, it is vital to recognize the overall implication that CDSS have in identifying cases needing interventions, whether actionable or not in nature. In fact, recognizing that alerts are in fact nonactionable demonstrates the complexity of antimicrobial therapy and the importance of ASP personnel with expertise to help differentiate alerts needing intervention.

There are important limitations to note from this study. First, during the preimplementation phase, there was no formal antimicrobial stewardship service. However, clinical pharmacy specialists rounding with the primary or infectious diseases consult teams may have made interventions that are not accounted for in the data analysis. In addition, the preimplementation phase alerts were reviewed retrospectively based on criteria defined for alert generation in the postimplementation phase. While this method has been previously used,6 it may have led to fewer alerts generated in the preimplementation phase and to a difference in determining which alerts were deemed actionable.

Conclusion

An important role and focus of ASPs considering implementation of CDSS will be to build alerts that are based on institutional and program needs. Alerts should focus on optimizing the appropriate use of antimicrobials and improving upon the time spent completing daily ASP tasks. In fact, as ASP’s defined roles continue to expand, focusing effort to build alerts that are actionable in nature will be of vital importance to help redistribute time needed to manage other ASP-related tasks and opportunities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the society for healthcare epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Infectious Diseases Society of America. The 10x’20 initiative: pursuing a global commitment to develop 10 new antibacterial drugs by 2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1081-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance//pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2015.

- 4. Forrest GN, Van Schooneveld TC, Kullar R, Schulz LT, Duong P, Postelnick M. Use of electronic health records and clinical decision support systems for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(S3):S122-S133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kullar R, Goff DA, Schulz LT, Fox BC, Rose WE. The “epic” challenge of optimizing antimicrobial stewardship: the role of electronic medical records and technology. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(7):1005-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hermsen ED, Van Shooneveld TC, Sayles H, Rupp ME. Implementation of a clinical decision support system for antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(4):412-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGregor JC, Weeks E, Forrest GN, et al. Impact of a computerized clinical decision support system on reducing inappropriate antimicrobial use: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:378-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel J, Esterly JS, Scheetz MH, Bolon MK, Postelnick MJ. Effective use of a clinical decision-support system to advance antimicrobial stewardship. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(18):1543-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]