Abstract

Background: Appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy is associated with improved outcomes of patients with Gram-negative bloodstream infections (BSI). Objective: Development of evidence-based institutional management guidelines for empirical antimicrobial therapy of Gram-negative BSI. Methods: Hospitalized adults with Gram-negative BSI in 2011-2012 at Palmetto Health hospitals in Columbia, SC, USA, were identified. Logistic regression was used to examine the association between site of infection acquisition and BSI due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa or chromosomally mediated AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CAE). Antimicrobial susceptibility rates of bloodstream isolates were stratified by site of acquisition and acute severity of illness. Retained antimicrobial regimens had predefined susceptibility rates ≥90% for noncritically ill and ≥95% for critically ill patients. Results: Among 390 patients, health care–associated (odds ratio [OR]: 3.0, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5-6.3] and hospital-acquired sites of acquisition (OR: 3.7, 95% CI: 1.6-8.4) were identified as risk factors for BSI due to P aeruginosa or CAE, compared with community-acquired BSI (referent). Based on stratified bloodstream antibiogram, ceftriaxone met predefined susceptibility criteria for community-acquired BSI in noncritically ill patients (95%). Cefepime and piperacillin-tazobactam monotherapy achieved predefined susceptibility criteria in noncritically ill (95% both) and critically ill patients with health care–associated and hospital-acquired BSI (96% and 97%, respectively) and critically ill patients with community-acquired BSI (100% both). Conclusions: Incorporation of site of acquisition, local antimicrobial susceptibility rates, and acute severity of illness into institutional guidelines provides objective evidence-based approach for optimizing empirical antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative BSI. The suggested methodology provides a framework for guideline development in other institutions.

Keywords: bacteremia, sepsis, antibiotics, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae

Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSI) have a significant impact on the morbidity and mortality in the general population as nearly 500 000 individuals develop BSI annually in the United States, contributing to 75 000 deaths.1 Adequate antimicrobial therapy is a key factor in reducing the burden of BSI, as inadequate antimicrobial therapy has been associated with increased mortality, cost, and length of stay in the hospital.2-5 Despite the extensive use of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents, it is alarming that 15% to 30% of patients with BSI still receive inadequate empirical therapy.6,7

The initial selection of the empirical antimicrobial regimen in patients with Gram-negative BSI is a difficult task due to lack of knowledge of the identification of the bloodstream isolate and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility results within 72 hours of presentation. Therefore, the development of local guidelines for management of BSI may be an effective tool to improve empirical antimicrobial therapy and hence patient outcomes.1

Antimicrobial stewardship programs play an important role in the development of institutional management guidelines in hospitalized patients with serious infections.8 Modification of national guidelines to tailor to the specific characteristics of an institution is an important step in development of local guidelines. However, lack of national guidelines for management of Gram-negative BSI emphasizes the need for antimicrobial stewardship programs to develop institutional management recommendations to guide empirical antimicrobial therapy based on local data. The aim of the study was to develop institutional guidelines for empirical antimicrobial therapy of Gram-negative BSI based on site of infection acquisition, local bloodstream antibiogram, and acute severity of illness.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted at Palmetto Health Richland and Baptist hospitals in Columbia, SC, USA. The two hospitals predominantly serve the population of Richland County and surrounding counties in central South Carolina. Restricted antimicrobial agents with Gram-negative activity at both hospital formularies at the time of study included carbapenems, ceftaroline, and tigecycline. The Institutional Review Board of the two hospitals approved the study and waived informed consent.

Definitions

Gram-negative BSI was defined as the growth of any aerobic Gram-negative bacillus in a blood culture. The source of BSI was defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria.9 The site of infection acquisition was classified into community-acquired, health care–associated, and hospital-acquired as previously defined.10 Adequacy of empirical antimicrobial therapy was defined based on dosing, route of administration, and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing as previously defined.3 Briefly, empirical antimicrobial therapy was considered adequate if (1) bloodstream isolate was susceptible to empirical agent based on in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility results using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria; (2) empirical antimicrobial agent was administered intravenously, with the exception of fluoroquinolones which were considered appropriate if administered orally in hemodynamically stable patients due to high bioavailability; and (3) patient received at least the minimum recommended dose of an antimicrobial agent according to the medication package insert for creatinine clearance at the time of BSI.

Case Ascertainment

All patients with BSI due to aerobic Gram-negative bacilli from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2012, were identified through microbiology laboratory databases. Hospitalized adult patients with first episodes of monomicrobial Gram-negative BSI were included in the study (n = 390). Patients <18 years old (n = 62), polymicrobial BSI (n = 79), recurrent episodes of BSI (n = 24), and patients who were treated outside the hospital (n = 23) were excluded.

Guideline Development and Assessment

Hospital-acquired and health care–associated sites of acquisition have been previously identified as risk factors for BSI due to Gram-negative bacilli that inherently harbor antimicrobial resistance genes such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and chromosomally mediated AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CAE), including Enterobacter, Citrobacter, and Serratia species.11,12 The first step in guideline development was to confirm this finding in the local setting using a retrospective case-control design. Second, in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility rates of bloodstream isolates for various antimicrobial agents and combinations regimens were examined in each site of acquisition. Antimicrobial agents with ≥90% in vitro susceptibility rates were retained. Third, patients were stratified by acute severity of illness using the Pitt bacteremia score.13 Antimicrobial regimens were retained if susceptibility rates were ≥90% for noncritically ill patients (Pitt bacteremia score <4) and ≥95% for critically ill patients (Pitt bacteremia score ≥4). Minimum susceptibilities of 90% and 95% for recommended antimicrobial regimens in noncritically ill and critically ill patients, respectively, represented the 90th percentile of responses to a large survey that was conducted among antimicrobial stewardship pharmacists.14 The preference for selection into institutional guidelines was given for monotherapy of nonrestricted agents. If monotherapy of all nonrestricted agents did not meet predefined susceptibility criteria in any category, restricted antimicrobial agents and combination regimens were included for selection in the respective category.

After management guidelines were developed, potential to improve the adequacy of empirical antimicrobial therapy and impact on utilization of broad-spectrum antibiotics was evaluated. First, the adequacy of empirical antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative BSI in the historic cohort was compared with projected adequacy if the guidelines were fully implemented. Second, the proportion of patients who received empirical antipseudomonal agents in the historic cohort was compared with projected use after guidelines implementation.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression was used to examine impact of site of infection acquisition on risk of BSI due to P aeruginosa or CAE. Demographics and clinical variables were collected from electronic medical records in patients with BSI due to P aeruginosa or CAE (cases) and other Gram-negative bacilli (controls), including age, sex, ethnicity, chronic comorbidities, and site of infection acquisition.

JMP (version 11.0, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) was used for statistical analysis. The level of significance for statistical testing was defined as P < .05 (2-sided).

Results

Over the 2-year study period, 390 patients with Gram-negative BSI were included from the 2 hospitals. Overall, the median age was 66 years, 229 (59%) were women, and the urinary tract (216; 55%) was the most common source of infection. The majority of patients had either community-acquired (161; 41%) or health care–associated BSI (159; 41%), whereas the remaining 70 patients (18%) had hospital-acquired infections (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Gram-Negative Bloodstream Infections.

| Variable | (n = 390) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 66 (55-78) |

| Female sex | 229 (59) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 191 (49) |

| African American | 188 (48) |

| Other | 11 (3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 144 (37) |

| End-stage renal disease | 38 (10) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 6 (2) |

| Malignancy | 70 (18) |

| Site of acquisition | |

| Community-acquired | 161 (41) |

| Health care–associated | 159 (41) |

| Hospital-acquired | 70 (18) |

| Source of infection | |

| Urinary tract | 216 (55) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 50 (13) |

| Central venous catheter | 35 (9) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 17 (4) |

| Respiratory tract | 12 (3) |

| Other | 8 (2) |

| Unknown | 52 (13) |

Note. Data are shown as number (%) unless otherwise specified. IQR = interquartile range.

Escherichia coli was predominantly the most common bloodstream isolate among community-acquired and health care–associated BSI accounting for two-thirds and one-half of cases, respectively (Table 2). It represented one-third of hospital-acquired bloodstream isolates, ranking second just behind Klebsiella species. Combined, P aeruginosa and CAE were more common in hospital-acquired (16; 23%) and health care–associated (31; 19%) than in community-acquired BSI (12; 7%). The site of infection acquisition identified patients at risk of BSI due to P aeruginosa or CAE. Patients with health care–associated and hospital-acquired BSI were nearly 3 times more likely to have BSI due to P aeruginosa or CAE as compared with those with community-acquired BSI (Table 3).

Table 2.

Microbiology of Gram-Negative Bloodstream Infections by Site of Acquisition.

| Bacteria | Community-acquired (n = 161) | Health care–associated (n = 159) | Hospital-acquired (n = 70) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 106 (66) | 79 (50) | 22 (31) |

| Klebsiella species | 24 (15) | 27 (17) | 26 (37) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 12 (7) | 16 (10) | 3 (4) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 4 (2) | 10 (6) | 6 (9) |

| Enterobacter species | 4 (2) | 10 (6) | 5 (7) |

| Serratia species | 1 (1) | 8 (5) | 4 (6) |

| Citrobacter species | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 7 (4) | 6 (4) | 3 (4) |

Note. Data are shown as number (%).

Table 3.

Risk Factors of Bloodstream Infections Due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Chromosomally Mediated AmpC-Producing Enterobacteriaceae.

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per decade) | 0.96 | (0.82-1.31) | .64 |

| Male sex | 1.34 | (0.77-2.35) | .30 |

| White ethnicity | 0.93 | (0.53-1.62) | .80 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.86 | (0.47-1.52) | .60 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1.12 | (0.06-7.14) | .92 |

| Cancer | 1.36 | (0.67-2.62) | .38 |

| Indwelling urinary catheter | 1.45 | (0.52-3.50) | .44 |

| Site of acquisition | |||

| Community-acquired | Referent | ||

| Health care–associated | 3.01 | (1.52-6.32) | .001 |

| Hospital-acquired | 3.68 | (1.64-8.44) | .002 |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

In vitro antimicrobial susceptibilities of Gram-negative bloodstream isolates to various antimicrobial agents and combination regimens by site of infection acquisition are demonstrated in Table 4. Ceftriaxone was the only nonrestricted nonantipseudomonal agent that provided ≥90% in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility for community-acquired Gram-negative bloodstream isolates. Three nonrestricted antipseudomonal agents, including two beta-lactams (cefepime and piperacillin-tazobactam) and gentamicin, had ≥90% susceptibility against both health care–associated and hospital-acquired Gram-negative bloodstream isolates. Because there was marginal difference between in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility rates of health care–associated and hospital-acquired Gram-negative bloodstream isolates, the two groups were merged together.

Table 4.

In Vitro Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bloodstream Isolates by Site of Acquisition.

| Antimicrobial agent/combination | Community-acquired (n = 161) | Health care–associated (n = 159) | Hospital-acquired (n = 70) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 63 (39) | 47 (30) | 17 (24) |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 112/160 (70) | 99/158 (63) | 46 (66) |

| Cefazolin | 128/160 (80) | 112 (70) | 47 (67) |

| Ceftriaxone | 151 (94) | 139 (87) | 58/69 (84) |

| Cefepime | 156 (97) | 152 (96) | 66 (96) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 157/159 (99) | 151/157 (96) | 65/69 (94) |

| Ertapenem | 157 (98) | 149 (94) | 64 (91) |

| Meropenem | 161 (100) | 158 (99) | 68 (97) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 134 (83) | 123/158 (78) | 60/68 (88) |

| Gentamicin | 147/158 (93) | 148/158 (94) | 63/69 (91) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 126/160 (79) | 119/159 (75) | 53 (76) |

| Cefepime + gentamicin | 157 (98) | 155/159 (97) | 67/69 (97) |

| Cefepime + ciprofloxacin | 158 (98) | 152 (96) | 66/69 (96) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam + gentamicin | 159 (99) | 155/158 (98) | 67 (96) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam + ciprofloxacin | 159/160 (99) | 152/158 (96) | 66/69 (96) |

| Meropenem + gentamicin | 161 (100) | 159 (100) | 69 (99) |

| Meropenem + ciprofloxacin | 161 (100) | 158 (99) | 69/69 (100) |

Note. Data show number of susceptible isolates (%) or number of susceptible/number of tested isolates (%), if not all isolates were tested.

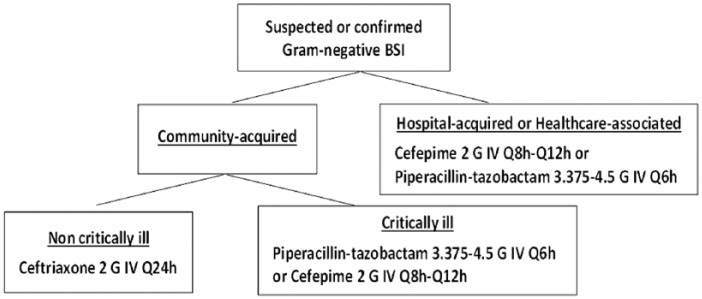

Next, patients were stratified based on site of acquisition (community-acquired vs health care–associated/hospital-acquired) and acute severity of illness using the Pitt bacteremia score (Table 5). Utilizing stratified bloodstream antibiogram, ceftriaxone was selected for community-acquired BSI in noncritically ill patients based on narrower spectrum of activity compared with the remaining nonrestricted agents. Cefepime and piperacillin-tazobactam were the only nonrestricted agents that met predefined criteria in critically ill patients with health care–associated/hospital-acquired BSI. The two antipseudomonal beta-lactams were selected over gentamicin in the remaining categories based on preferable side effects profile. An algorithm was developed to guide empirical antimicrobial therapy in patients with Gram-negative BSI while awaiting final blood culture results (Figure 1).

Table 5.

In Vitro Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bloodstream Isolates by Site of Acquisition and Acute Severity of Illness.

| Antibiotic | Community-acquired |

Health care–associated or hospital-acquired |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitt score <4 (n = 128) | Pitt score ≥4 (n = 33) | Pitt score <4 (n = 152) | Pitt score ≥4 (n = 77) | |

| Ceftriaxone | 121 (95) | 30 (91) | NA | NA |

| Cefepime | 123 (96) | 33 (100) | 144 (95) | 74 (96) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 124/126 (98) | 33 (100) | 143/151 (95) | 73/75 (97) |

| Gentamicin | 115/126 (91) | 32 (97) | 142/151 (94) | 69/76 (91) |

Note. Data show number of susceptible isolates (%) or number of susceptible/number of tested isolates (%), if not all isolates were tested. NA = not appropriate.

Figure 1.

Guidelines for empirical antimicrobial therapy of gram-negative bloodstream infections.

Note. BSI = bloodstream infection; IV = intravenous.

In the current cohort, 92% of patients received adequate empirical antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative BSI and 82% received at least one antipseudomonal agent empirically. Implementation of proposed guidelines is projected to increase adequacy of empirical antimicrobial therapy to over 95% and reduce utilization of empirical antipseudomonal agents to 67% (262/390) of patients.

Discussion

Improvement in quality of care and reduction in antimicrobial resistance rates are 2 major principles of antimicrobial stewardship.15 Institutional guidelines for management of hospitalized patients with serious infections are essential tools to improve quality of care by optimization of empirical antimicrobial therapy. In addition, if these guidelines advocate for reduction in utilization of broad-spectrum antimicrobial regimens, then implementation may contribute to reduction in antimicrobial resistance rates as well.8 This article outlines suggested methodology for development of evidence-based institutional guidelines for management of Gram-negative BSI utilizing local data, which may provide framework for other institutions.

It is important for institutional management guidelines to represent high-quality evidence-based data. At the same time, guidelines that are practical and user friendly are more likely to be accepted and implemented across the institution. For this reason, many institutional management guidelines are centered midway between science and practice, and the current guidelines are an example of this role. The study did not aim to develop a model to predict BSI due to resistant Gram-negative bacilli. That would have required inclusion of many additional clinical variables and detailed history of prior antibiotic use in each patient.16,17 Rather, the goal of this study was to develop institutional guidelines for empirical therapy of Gram-negative BSI using clinical criteria that most health care providers were familiar with regardless of specialty, such as site of infection acquisition and acute severity of illness. The Pitt bacteremia score was used as a measure of acute severity of illness to maintain consistent definition of critically ill throughout guideline development. Health care providers were encouraged to use objective methods to determine acute severity of illness and prognosis of patients with BSI.13,18 However, the definition of critically ill was expanded to include patients who required admission to the intensive care unit to make the guidelines more practical for health care providers who were not familiar with such scores (Supplement 1).

Using antimicrobial agents with ≥90% susceptibility in noncritically ill patients with BSI is consistent with national guidelines for management of acute pyelonephritis and nosocomial pneumonia.19,20 However, the predefined minimum susceptibility threshold of ≥95% for critically ill patients in this study may seem optimistic in areas with high rates of antimicrobial resistance. These cutoffs were derived from a large national survey of antimicrobial stewardship pharmacists who have knowledge of antimicrobial resistance rates and local hospital epidemiology.14 It was conceivable to select higher minimum antimicrobial susceptibility cutoff in critically ill patients because survival benefit from adequate empirical antimicrobial therapy was clearly demonstrated in this population.3 However, these cutoffs remain subject for revision at the discretion of local antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Despite relatively high overall susceptibility rates of bloodstream isolates to beta-lactams in the current study, susceptibility to ampicillin-sulbactam did not exceed 70% even in community-acquired bloodstream isolates. Similarly, ciprofloxacin did not meet the predefined susceptibility selection criteria in any category. This is consistent with data from other population-based settings in the USA.21 The predefined minimum susceptibility thresholds in this study were achieved by ceftriaxone in noncritically ill patients with community-acquired BSI and either piperacillin-tazobactam or cefepime in critically ill patients with community-acquired BSI and those with health care–associated or hospital-acquired BSI. The relatively low incidence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae among the local bloodstream isolates likely allowed the use of carbapenem-sparing regimens as first line treatment options. Overall, 3.3% (13/390) of Gram-negative bacilli in this study demonstrated ESBL production (3.1% [4/128] in noncritically ill, community-acquired group and 3.4% [9/262] in the other stratum of the guidelines). Moreover, it was noted in the current study that adding a fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside to beta-lactams provided minimal improvement in antimicrobial susceptibility rates, regardless of site of acquisition. This argued against the nonstratified use of combination antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative BSI in our local population.

It was projected that implementation of the current management guidelines would improve the adequacy of empirical antimicrobial therapy to >95%. Multiple measures were taken to improve the adequacy of antimicrobial therapy in the remaining patients. Providers were highly encouraged to contact the antimicrobial stewardship and support team or request an infectious diseases consultation for more specific recommendations on empirical antimicrobial therapy in patients with unique clinical situations such as severe beta-lactam allergy or in the case of suspicion of a particular antimicrobial resistance mechanism, including ESBL production, as in Supplement 1.22-25 Moreover, the antimicrobial stewardship and support team would prospectively follow every patient to ensure proper implementation of guidelines and provide additional recommendations in patients with risk factors for antimicrobial resistance.

Guideline implementation is also projected to reduce overall utilization of antipseudomonal agents. Prospective monitoring by the antimicrobial stewardship and support team to ensure appropriate de-escalation of antimicrobial regimen based on bacterial identification and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing results may also shorten the duration of antipseudomonal therapy. Because the guidelines provide reassurance to health care providers that monotherapy adequately covers ≥95% of bloodstream isolates, it is expected that use of combination antimicrobial therapy may also decline after implementation.

The current guidelines have limitations that may impact implementation at other institutions. First, accurately defining the site of infection acquisition may be challenging in patients with unknown or limited medical histories within the local health care system. Second, because all recommended regimens constitute beta-lactam antibiotics, mechanisms to screen patients and recommend alternative therapy in those with severe beta-lactam allergy are necessary. Finally, there are potential risks of not providing initial adequate coverage for P aeruginosa in noncritically ill patients with community-acquired BSI and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae overall, particularly in settings with higher incidence of BSI due to these resistant bacteria than the current population. The use of more robust models to predict the risk of BSI due to P aeruginosa and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae has been demonstrated to improve both the adequacy of empirical therapy and antimicrobial utilization.16,26

In summary, the study provides suggested methods for development of institutional management guidelines for Gram-negative BSI based on site of acquisition, local antimicrobial susceptibility rates of bloodstream isolates, and acute severity of illness. Implementation of these institutional guidelines may improve the adequacy of empirical antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative BSI while reducing utilization of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Palmetto Health Antimicrobial Stewardship and Support Team and Microbiology Laboratory in South Carolina, USA, for their help in facilitating the conduct of this study.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The preliminary results of this study were presented in part at IDWeek; October 2014; Philadelphia, PA, USA (Abstract No. 47023).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: P.B.B. served as a content developer and speaker for Rockpointe Corporation and FreeCe.com.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study received funding from the Grant in Aid Program at Palmetto Health Richland in Columbia, SC, USA. Funding source had no role in study design.

References

- 1. Goto M, Al-Hasan MN. Overall burden of bloodstream infection and nosocomial bloodstream infection in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:501-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Retamar P, Portillo MM, López-Prieto MD, et al. Impact of inadequate empirical therapy on the mortality of patients with bloodstream infections: a propensity score-based analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:472-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cain SE, Kohn J, Bookstaver PB, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Stratification of the impact of inappropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative bloodstream infections by predicted prognosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:245-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shorr AF, Micek ST, Welch EC, Doherty JA, Reichley RM, Kollef MH. Inappropriate antibiotic therapy in Gram-negative sepsis increases hospital length of stay. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:46-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brigmon MM, Bookstaver BP, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Impact of fluoroquinolone resistance in Gram-negative bloodstream infections on healthcare utilization. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:843-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pien BC, Sundaram P, Raoof N, et al. The clinical and prognostic importance of positive blood cultures in adults. Am J Med. 2010;123:819-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sogaard M, Norgaard M, Dethlefsen C, Schonheyder HC. Temporal changes in the incidence and 30-day mortality associated with bacteremia in hospitalized patients from 1992 through 2006: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:159-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, et al. Health care–associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:791-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheong HS, Kang CI, Wi YM, et al. Clinical significance and predictors of community-onset Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Am J Med. 2008;121:709-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Al-Hasan MN, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Impact of healthcare-associated acquisition on community-onset Gram-negative bloodstream infection: a population-based study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1163-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paterson DL, Ko WC, Von Gottberg A, et al. International prospective study of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in nosocomial infections. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bookstaver PB, Hagedorn M, Haggard E, et al. Empirical antibiotic selection: a survey evaluating decision making among providers. American Society of Hospital Pharmacists Midyear Clinical Meeting; December 2014; Anaheim, CA (Abstract No. 5-461). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fishman N. Antimicrobial stewardship. Am J Med. 2006;119:S53-S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hammer KL, Justo JA, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Differential effect of prior β-lactams and fluoroquinolones on risk of bloodstream infections secondary to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;87:87-91. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hammer KL, Stoessel A, Justo JA, et al. Association between chronic hemodialysis and bloodstream infections caused by chromosomally mediated AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:1611-1616. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Al-Hasan MN, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Predictive scoring model of mortality in Gram-negative bloodstream infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:948-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America, European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e103-e120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61-e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Hasan MN, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Antimicrobial resistance trends of Escherichia coli bloodstream isolates: a population-based study, 1998–2007. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:169-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pichichero ME. Cephalosporins can be prescribed safely for penicillin-allergic patients. J Fam Pract. 2006;55:106-112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koliscak LP, Johnson JW, Beardsley JR, et al. Optimizing empiric antibiotic therapy in patients with severe β-lactam allergy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5918-5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, Bassetti M, et al. Identifying patients harboring extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae on hospital admission: derivation and validation of a scoring system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3485-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Orsi GB, Bencardino A, Vena A, et al. Patient risk factors for outer membrane permeability and KPC-producing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolation: results of a double case-control study. Infection. 2013;41:61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Augustine MR, Testerman TL, Justo JA, et al. Clinical risk score for prediction of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae in bloodstream isolates. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]