Abstract

Patient activation, often conceptualized as an individual trait, contributes to mental health outcomes. This study assessed the relational contributors to activation by estimating the longitudinal association of patient-provider communication and two factors of therapeutic alliance (agreement on tasks/goals and bond), with patient activation. Participants were patients (n=264) from 13 community-based mental health clinics across the United States. In multivariate models, controlling for patients' individual and clinical characteristics, the task/goal factor of therapeutic alliance emerged as a significant and independent predictor of greater change in PAM scores. Improving patient activation may require addressing patient-provider interactions such as coming to collaborative agreement on the tasks/goals of care.

Keywords: Patient activation, mental health

Introduction

Patient activation, defined as one's readiness and willingness to take on the role of managing one's own health and healthcare, has emerged as an important contributor to management of chronic conditions, including mental health (Hibbard, Mahoney, Stockard, & Tusler, 2005; Hibbard, Stockard, Mahoney, & Tusler, 2004).The Patient Activation Measure (PAM) is a well validated scale that focuses on patients as individual agents of their own care management by assessing knowledge about chronic conditions such as mental health disorders, beliefs about illness and medical care, and self-efficacy for self-care (Hibbard et al., 2004). Greater patient activation has been associated with improved health behaviors, disease self-management behaviors such as adherence to drug regimens, and an array of health outcomes including improved mental health (Hibbard, Mahoney, Stock, & Tusler, 2007; Mosen et al., 2007; Remmers et al., 2009).

In many studies, patient activation has been conceptualized as an individual attribute that precedes improved health processes and outcomes(Remmers et al., 2009). As such, variations in levels of activation have been identified across different groups of patients; e.g., clinically meaningful differences in activation levels have been noted for Black and Latino adults in comparison to whites (Cunningham, Hibbard, & Gibbons, 2011; Hibbard et al., 2008). Social and clinical factors associated with activation levels include English language abilities, nationality (immigrant versus US born), and self-assessment of health (Alegria, Sribney, Perez, Laderman, & Keefe, 2009; Alexander, Hearld, Mittler, & Harvey, 2012; Hibbard et al., 2008). Thus, most interventions designed to increase activation are directed at patients. (Alegria et al., 2008; Deen, Lu, Rothstein, Santana, & Gold).

While activation may to some degree be individually determined, it can be argued that most patients in mental health care do not achieve activation alone, but rather within a dyadic relationship with their provider. The degree to which providers promote and clearly communicate a shared understanding of patients' illness and the importance of patient self-care within a trusting relationship likely contributes to patients' belief that they are able to manage their own care.

Patient-provider communication may contribute to patient activation through discussion of specific content, such as the importance of self-management, skills for self-care, and through sharing educational materials that facilitate self-care (Street, Makoul, Arora, & Epstein, 2009). Provider communication also influences activation through communication styles that elicit patients' opinions and facilitate patient involvement in care (Roter et al., 1997). Provider factors are particularly influential on the quality of communication for racial/ethnic minority patients (Cooper, Beach, Johnson, & Inui, 2006; Ghods et al., 2008). So while the literature has conceptualized patient participation as leading to improved communication, (Alegria et al., 2009; Cegala & Post, 2009) providers' attention to communication quality may in fact be a prerequisite for activation.

Therapeutic alliance, a related concept that may contribute to patient activation, is defined as the degree to which the patient and mental health provider are “engaged in collaborative, purposive work” (Baldwin, Wampold, & Imel, 2007). Research using the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI), (Horvath AO & Greenberg LS, 1986) the most common scale measuring therapeutic alliance, frequently identifies alliance as having two factors: 1) agreement on the tasks/goals to be pursued in treatment and the means or strategies to accomplish the treatment goals (the task needs to fit the patients' lifestyle, worldview, and expectations for therapy), and 2) bond, which captures the human relationship between provider and patient (e.g. trust, respect, and caring between the provider and the patient) (Andrusyna, Tang, DeRubeis, & Luborsky, 2001; Hatcher & Barends, 1996; Ross, Polaschek, & Wilson, 2011). Alliance is greater for collaborative providers who validate patients' experiences and emotions, convey belief in patients' ability to use what has been learned in treatment, provide education regarding treatment processes and self-care, convey belief that patients can achieve defined goals, and reinforce progress toward goals (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2003; Bedi, 2006). These practices likely contribute to patients' greater confidence in their ability to take charge of their own health and healthcare, and generate a shared dyadic understanding of therapeutic goals and expected outcomes. The collaborative approach leading to a strong bond increases dyadic trust, a factor associated with increased patient activation (Alexander et al., 2012).

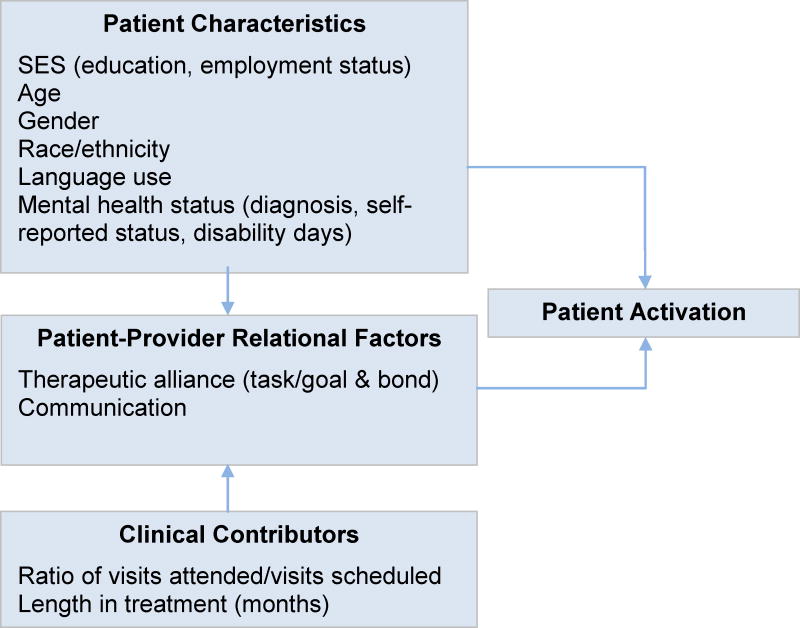

Thus, a dyadic relationship characterized by a strong therapeutic alliance and quality communication may create the conditions for patients to become activated in mental health treatment. Despite this potentially important contribution, these factors, to the best of our knowledge, have not been considered previously in relation to patient activation, particularly in longitudinal studies. Furthermore, few studies have evaluated activation among patients from community-based mental health clinics caring for diverse and underserved populations. The purpose of this paper is therefore to estimate the unique effects of communication and therapeutic alliance on patient activation both cross-sectionally and longitudinally in patients attending community-based mental health clinics. In Figure 1, our conceptual model outlines the relationship between the factors of therapeutic alliance and communication with PAM scores. We expect these relational factors to have a unique contribution to patient activation after adjustment for individual patient characteristics and clinical contributors previously shown to relate to activation (Alegria et al., 2009; Deen et al.). Our hypotheses are that 1) at baseline, PAM scores will be associated with communication and therapeutic alliance (both bond and task/goal factors), adjusting for clinical and patient characteristics; and 2) communication and therapeutic alliance will be associated with greater change in PAM scores, adjusting for baseline PAM, clinical and patient characteristics. Since therapeutic alliance and communication are modifiable provider-patient factors, the result of this research could inform interventions for healthcare systems to enhance patient activation.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

Methods

Sample and setting

This study draws from participants in the control group of the DECIDE intervention, a multisite randomized clinical trial assessing a patient-focused intervention to increase mental health patient activation and self-management. Recruitment occurred between February 2009 and June 2011 and follow-up interviews were completed by October 2011. The sample for this analysis was limited to the control group so as not to confound the naturalistic changes in therapeutic alliance and activation (Alegria et al., 2014).

Participants were recruited from 13 outpatient clinics providing mental health services across the country. Eight of these clinics were affiliated with academic health centers. These clinics were located in Massachusetts (five clinics), Minnesota (three clinics), North Carolina (two clinics), New Jersey (one clinic), New York (one clinic), and Puerto Rico (one clinic). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Cambridge Health Alliance and at all participating sites. Patients were eligible to participate if they were between the ages of 18 and 70 years and were currently receiving psychotherapy and/or psychopharmacology treatment. Prior to consent, participants were screened for suicidality and the capacity to consent. Of 1472 mental health patients who were approached across all clinics, 807 were screened. Of those screened, 69 were ineligible due to suicidal ideation (n=56) or a lack of capacity to consent (n=13), while 14 declined to participate. A total of 724 were randomized to the intervention arm (n=372) or the control arm (n=352) of the study. There were a total of 88 participants lost to follow up in the control group. Of the remaining 264 approximately 32% were missing on data for PAM at baseline because this measure was introduced as an additional assessment of activation 6 months after the study had begun. Those without baseline PAM were excluded from the present analysis yielding a final sample of 170. Rates of missingness for the remaining variables in the analysis ranged from 0%-1.5%. Missing data were imputed using demographic characteristics, time in study, and available outcome scores so that all participants could be included in the analyses. Multiple imputation was completed using SAS procedure PROC MI with the number of imputations repeated 10 times (SAS Institute, 2008). Results were combined across multiple imputations using methods described by Rubin (Rubin & Schenker, 1986).

Data collection

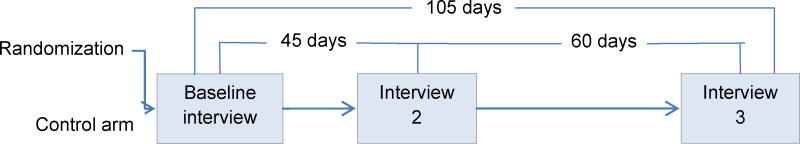

Detailed assessments of patient activation, therapeutic alliance, and other potential contributors to activation such as mental health severity were collected at three points in time by trained, bilingual (English and Spanish) research assistants via computer assisted interview in person or over the phone. Changes in outcomes were assessed at approximately 45 and 105 days (Figure 2). This analysis focuses on the baseline to interview 3 period. In addition, clinical administrative data including diagnoses and appointment attendance were captured from chart reviews at each site.

Figure 2. Timing of Participant Interviews.

Measures

The dependent variable, patient activation, was assessed by the PAM, a unidimensional, interval-level 13 item scale capturing four key patient concepts: 1) Belief that taking an active role is important (“When all is said and done, I am the person who is responsible for taking care of my health”), 2) Confidence and knowledge to take action (“I know what each of my prescribed medications do”), 3) Taking action (“I have been able to maintain lifestyle changes”), and 4) Staying the course under stress (“I am confident I can figure out solutions when new problems arise with my health”) (Hibbard et al., 2005; Hibbard et al., 2004). Items are measured on 5-point, Likert-type scales with responses ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The items were summed for each patient and then standardized to range from 0-100 with higher numbers indicating greater activation. The PAM has strong psychometric properties in both English and Spanish.(Alegria et al., 2009; Hibbard et al., 2005; Hibbard et al., 2004)

Therapeutic alliance, was examined by the 12 item Working Alliance Inventory (WAI)-Short form, which is widely used to assess therapeutic alliance(Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989). Though theoretically defined as having three components, analytical approaches have frequently identified two factors as part of the WAI, tasks/goals, and bond; higher scores indicate more positive rating of the therapeutic alliance (Ross et al., 2011). Internal consistency indices for the total scale and each subscale are good (overall α=.89, task/goal factor α=.84, bond factor α=.83 for this study) (Hanson, Curry, & Bandalos, 2002). Representative items capturing task/goals are, “We have established a good understanding of the kind of changes that would be good for me,” and bond are, “I feel that my mental health provider appreciates me.”

Communication was assessed through the eleven item communication sub-scale from the Kim Alliance scale (Kim, Boren, & Solem, 2001). Attributes measured include bonding, provision of information, and expression of concerns. Sample items include, “Plain language is used by my provider” and “I feel my provider criticizes me too much.” This scale has well established psychometric properties; internal consistency for this study was high (α=.74) (Kim et al., 2001).

Clinical characteristics included measures of mental health severity as assessed by self-reported mental health status (poor through excellent), primary mental health diagnosis, and number of days unable to work due to a mental health problem during the past 30 days (disability days). Because participants were at different stages of treatment, we also controlled for the ratio of the number of visits attended to those scheduled in the six months prior to baseline, and self-reported length in treatment (in months) to control for the likely differences in therapeutic alliance related to the length that patient and provider have worked together (Kivlighan & Shaughnessy, 1995). Socio-demographic characteristics include sex, race/ethnicity (White, Latino, Black, Other), age (18-34, 35-49, 50-64, 65+), immigrant (versus US-born), education (0-11, 12+ years of education), employment status (full-time employment or not), and insurance status (private, public, other, uninsured).

Analysis

Preliminary unadjusted analyses describe baseline mean PAM, and change in PAM from baseline to interview 3 period, by patient and key clinical and socio-demographic characteristics described above. Adjusted Wald tests were used to test the significance of these differences. We then estimated a linear regression model (patients nested within sites) to identify associations between factors of therapeutic alliance and PAM at baseline, after adjustment for the clinical and socio-demographic characteristics described above, and accounting for variation by site.

Next, we estimated first a linear regression model, then a multilevel random intercepts linear regression models (patients nested within sites) of change in PAM upon baseline relational factors, adjusting for baseline PAM, patient characteristics, and clinical contributors identified above. Each component of our conceptual model was added sequentially to the regression model for a total of three models (Model A: Patient/provider relational factors; Model B: Model A + Patient Characteristics; and Model C: Model B + Clinical Contributors). This allowed us to assess the mediating influence of each component on the association between patient/provider relational factors and patient activation. Use of longitudinal data has the advantage over cross-sectional data of ruling out a reverse causal relationship (in this case, changes in change in PAM cannot cause baseline therapeutic alliance). While this analysis cannot present conclusive evidence of a causal relationship linking therapeutic alliance and change in PAM, it can lend support to the influence of relational factors on change in PAM described in the cross-sectional analysis. We include baseline PAM in this model because the influence of relational factors on change in PAM may be confounded by different baseline PAM scores. For example, individuals with PAM scores near the maximum at baseline cannot increase their scores to the same degree as individuals with lower scores.

To further assess the contribution of patient/provider relational factors we generated 6 supplemental multivariate models (3 baseline and 3 longitudinal), testing each factor separately in each model out of concern for collinearity between the factors, while adjusting for baseline PAM. All statistical procedures were conducted using Stata statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, 2008).

Results

Unadjusted analyses indicate that overall mean PAM scores increased on average from baseline (72.3) to follow-up by 2.6 points (range -37.6 to 34.8, SD 11.9) (Table 1). Participants with self-reported poor mental health status scored an average of 22 points lower on the PAM scale at baseline than those with excellent mental health, but their PAM scores increased 10 points over the study period, more than any other group. However, even with that increase, those with poor mental health still reported an average activation level approximately 10 points below those reporting excellent mental health. In terms of age, participants age 35-49 showed more increase in PAM scores over time than other age groups.

Table 1. Unadjusted rates of activation, therapeutic alliance, communication and change in activation by patient characteristics (n=170).

| Activation (baseline) |

Test | Therapeutic alliance (baseline) |

Test | Therapeutic alliance, task&goal (baseline) |

Test | Therapeutic alliance, bond (baseline) |

Test | Communication (baseline) |

Test | Change in Activation (T3- T1) |

Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value | Mean | SE | P value | |

| Total | 72.0 | 1.1 | 74.1 | 0.7 | 61.3 | 0.6 | 25.9 | 0.3 | 41.0 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.9 | ||||||

| Sex | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||

| Female | 72.3 | 1.4 | 0.74 | 73.9 | 0.9 | 0.72 | 61.2 | 0.8 | 0.94 | 25.7 | 0.3 | 0.39 | 41.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 0.37 |

| Male | 71.6 | 1.7 | . | 74.4 | 1.2 | . | 61.3 | 1.0 | . | 26.2 | 0.4 | . | 40.9 | 0.4 | . | 3.6 | 1.6 | . |

| Race/ethnicity | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| White | 70.7 | 2.2 | 0.42 | 69.4 | 1.8 | 0.00 | 57.5 | 1.5 | 0.00 | 24.2 | 0.7 | 0.00 | 39.7 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 0.96 |

| Latino | 72.3 | 1.3 | . | 77.1 | 0.7 | . | 63.5 | 0.6 | . | 27.0 | 0.2 | . | 41.9 | 0.2 | . | 2.2 | 1.2 | . |

| Black | 70.2 | 4.0 | . | 68.8 | 2.1 | . | 57.4 | 1.4 | . | 24.3 | 0.8 | . | 40.0 | 0.8 | . | 3.7 | 2.1 | . |

| Other | 78.7 | 3.3 | . | 74.9 | 3.5 | . | 62.1 | 3.0 | . | 25.8 | 1.1 | . | 40.6 | 1.5 | . | 2.5 | 3.8 | . |

| Age, yr | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| 18-34 | 71.4 | 2.3 | 0.99 | 75.0 | 1.5 | 0.91 | 62.4 | 1.2 | 0.76 | 26.2 | 0.5 | 0.69 | 41.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 0.19 |

| 35-49 | 72.4 | 1.7 | . | 73.9 | 1.1 | . | 61.2 | 0.9 | . | 25.7 | 0.4 | . | 40.9 | 0.4 | . | 4.5 | 1.3 | . |

| 50-64 | 72.0 | 1.8 | . | 73.7 | 1.3 | . | 60.7 | 1.1 | . | 26.0 | 0.5 | . | 41.0 | 0.4 | . | 0.2 | 1.5 | . |

| 65+ | 70.8 | 14.3 | . | 76.0 | 4.0 | . | 62.0 | 4.0 | . | 27.7 | 0.3 | . | 42.0 | 1.2 | . | 0.4 | 2.9 | . |

| Nativity | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| US-Born | 72.1 | 1.6 | 0.96 | 70.7 | 1.1 | 0.00 | 58.6 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 24.7 | 0.4 | 0.00 | 40.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.68 |

| Non US-Born | 72.0 | 1.5 | . | 77.6 | 0.7 | . | 64.0 | 0.6 | . | 27.1 | 0.2 | . | 42.0 | 0.2 | . | 2.9 | 1.2 | . |

| Education | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| 0-11 years | 72.0 | 2.1 | 1.00 | 75.9 | 1.1 | 0.07 | 62.7 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 26.5 | 0.4 | 0.11 | 41.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.35 |

| 12 or 12+ years | 72.0 | 1.3 | . | 73.2 | 0.9 | . | 60.6 | 0.7 | . | 25.6 | 0.3 | . | 40.8 | 0.3 | . | 3.1 | 1.1 | . |

| Employment Status | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Non-Employed | 70.9 | 1.3 | 0.10 | 73.7 | 0.9 | 0.40 | 61.0 | 0.7 | 0.43 | 25.8 | 0.3 | 0.42 | 40.9 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.93 |

| Employed | 74.9 | 1.7 | . | 75.1 | 1.3 | . | 62.0 | 1.2 | . | 26.3 | 0.5 | . | 41.3 | 0.4 | . | 2.7 | 1.5 | . |

| Insurance Status | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Uninsured | 74.1 | 2.3 | 0.29 | 76.0 | 1.5 | 0.52 | 62.8 | 1.3 | 0.49 | 26.3 | 0.5 | 0.82 | 41.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.48 |

| Private Only | 68.9 | 2.8 | . | 73.1 | 2.5 | . | 60.3 | 2.1 | . | 25.7 | 0.9 | . | 40.6 | 0.8 | . | 5.9 | 2.6 | . |

| Public Only | 71.8 | 1.4 | . | 73.6 | 0.9 | . | 60.9 | 0.7 | . | 25.8 | 0.3 | . | 40.9 | 0.3 | . | 1.8 | 1.1 | . |

| Other | 91.6 | . | . | 70.0 | . | . | 56.0 | . | . | 27.0 | . | . | 41.0 | . | . | 8.4 | . | . |

| Mental Health Status | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Excellent | 77.7 | 1.6 | 0.00 | 75.8 | 1.3 | 0.12 | 62.9 | 1.1 | 0.15 | 25.8 | 0.5 | 0.87 | 41.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.01 |

| Very good | 83.1 | 3.9 | . | 76.2 | 3.1 | . | 63.3 | 2.5 | . | 26.0 | 1.6 | . | 40.8 | 1.4 | . | 5.2 | 6.4 | . |

| Good | 79.4 | 2.6 | . | 75.6 | 1.4 | . | 62.6 | 1.1 | . | 26.0 | 0.5 | . | 40.9 | 0.5 | . | -3.0 | 3.4 | . |

| Fair | 69.6 | 1.5 | . | 73.6 | 1.1 | . | 60.5 | 0.9 | . | 26.1 | 0.4 | . | 41.3 | 0.4 | . | 3.1 | 1.1 | . |

| Poor | 55.5 | 3.7 | . | 69.1 | 2.8 | . | 57.9 | 2.1 | . | 25.1 | 1.0 | . | 40.3 | 0.7 | . | 10.0 | 3.5 | . |

| Diagnosis | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Depression | 71.0 | 1.5 | 0.37 | 73.4 | 1.0 | 0.61 | 60.6 | 0.8 | 0.60 | 25.8 | 0.3 | 0.81 | 40.9 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.49 |

| Anxiety | 74.6 | 3.6 | . | 73.0 | 2.9 | . | 60.3 | 2.5 | . | 25.6 | 1.0 | . | 40.8 | 1.1 | . | 5.8 | 2.4 | . |

| Bipolar | 74.9 | 3.2 | . | 75.1 | 2.7 | . | 62.4 | 2.2 | . | 25.9 | 0.9 | . | 41.6 | 0.8 | . | 2.1 | 3.3 | . |

| Psychotic Disorder | 77.8 | 4.5 | . | 78.9 | 1.5 | . | 64.9 | 1.5 | . | 27.7 | 0.2 | . | 42.6 | 0.4 | . | 4.3 | 3.7 | . |

| Adjustment | 76.1 | 2.8 | . | 76.2 | 2.0 | . | 63.1 | 1.7 | . | 25.9 | 0.9 | . | 41.1 | 0.8 | . | -0.5 | 3.4 | . |

| Other | 68.0 | 3.0 | . | 75.0 | 1.6 | . | 62.2 | 1.5 | . | 26.1 | 0.8 | . | 41.0 | 0.6 | . | 5.8 | 2.6 | . |

In three baseline cross-sectional models entering each of the patient/provider relational factors independently while adjusting for patient and clinical characteristics, the bond and task/goal factors of therapeutic alliance and communication were each positively associated with PAM scores (p= <.001 for all, results not shown). However, in baseline cross-sectional models including all patient-provider relational factors, adjusting for patient characteristics, and clinical contributors, the task/goal factor of therapeutic alliance was positively associated with PAM scores, while the bond factor and communication were non-significant (Table 2).

Table 2. Association of PAM with therapeutic alliance and communication adjusting for patient characteristics and clinical contributors at baseline (n=170).

| Predictors | PAM (base line) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | P value | |

| Therapeutic Alliance factor 1(task&goal) | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| Therapeutic Alliance factor 2(bond) | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.99 |

| Communication | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.50 |

| female (male as reference) | 3.01 | 2.25 | 0.18 |

| Race/Ethnicity (white as reference) | |||

| Latino | 0.29 | 3.53 | 0.94 |

| Black | 0.58 | 3.71 | 0.88 |

| Other | 6.79 | 4.62 | 0.14 |

| Age (18-34 as reference) | |||

| 35-49 | 2.94 | 2.74 | 0.28 |

| 50-64 | 2.53 | 2.95 | 0.39 |

| 65+ | -5.62 | 9.55 | 0.56 |

| Immigrant (US-born as reference) | -5.20 | 2.91 | 0.07 |

| Education (less than 12 yrs as reference) 12 or more than 12 yrs | -1.59 | 2.43 | 0.51 |

| Employed (unemployment as reference) | 1.48 | 2.53 | 0.56 |

| Insurance Status (uninsured as reference) | |||

| Private Only | -3.21 | 3.42 | 0.35 |

| Public Only | 0.99 | 2.51 | 0.69 |

| Other | 11.34 | 13.94 | 0.42 |

| Mental Health (good as reference) | |||

| Excellent | 6.47 | 2.44 | 0.01 |

| Very Good | -7.91 | 3.39 | 0.02 |

| Fair | 7.73 | 3.16 | 0.01 |

| Poor | 8.63 | 5.78 | 0.14 |

| Disability days | -0.25 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Diagnosis (depression as reference) | |||

| Anxiety Disorder | 1.36 | 3.52 | 0.70 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 1.84 | 3.62 | 0.61 |

| Psychotic Disorder | -2.79 | 5.69 | 0.62 |

| Adjustment Disorder | 0.51 | 3.78 | 0.89 |

| Other | -4.83 | 3.26 | 0.14 |

| Attendance ratio during 180 days before baseline | -0.14 | 5.45 | 0.98 |

| Length in Treatment (months) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.65 |

| Constant | 26.45 | 14.43 | 0.07 |

In longitudinal analyses, the task/goal factor of therapeutic alliance was significantly associated with change in PAM scores when adjusting for baseline PAM score but not patient characteristics or clinical contributors in a simple linear regression model (p=0.024, results not shown) and also in the random intercepts multi-level linear regression model (Table 3, Model A). Adding in first, patient characteristics (Model B) and then clinical contributors (Model C), the task/goal factor of therapeutic alliance remained significant (p=<.0001 for both). Communication and the bond factor of therapeutic alliance were non-significant in all three longitudinal models predicting follow up PAM scores (Table 3, Models A-C). In supplemental longitudinal analysis controlling only for baseline PAM scores and entering the relational factors separately, we identified increased baseline therapeutic alliance on tasks/goals to predict greater change in PAM scores but found no significant association between the bond factor or communication and change in PAM scores (results not shown).

Table 3. Random intercepts multi-level linear regression model of change in PAM between baseline and follow-up conditional on 2 factors of therapeutic alliance, communication, PAM at baseline, participant characteristics (sociodemographics, mental health status, disability) and clinical contributors (diagnosis, attendence ratio, length of treatment) (n=170).

| Predictor | PAM (follow-up) | PAM (follow-up) | PAM(follow-up) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | P value | Beta | SE | P value | Beta | SE | P value | |

| Therapeutic Alliance Factor 1 (task & goal) | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.19 | 0.016 | 0.46 | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| Therapeutic Alliance Factor 2 (bond) | -0.31 | 0.38 | 0.42 | -0.28 | 0.41 | 0.50 | -0.29 | 0.42 | 0.49 |

| Communication | -0.23 | 0.36 | 0.52 | -0.24 | 0.38 | 0.53 | -0.24 | 0.38 | 0.53 |

| PAM at baseline | -0.38 | 0.06 | <.0001 | -0.38 | 0.08 | <.0001 | -0.38 | 0.08 | <.0001 |

| Female (male as reference) | -2.11 | 1.96 | 0.28 | -2.26 | 2.04 | 0.27 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity (white as reference) | |||||||||

| Latino | -2.58 | 3.09 | 0.40 | -2.38 | 3.18 | 0.45 | |||

| Black | 2.46 | 3.30 | 0.46 | 2.50 | 3.34 | 0.45 | |||

| Other | 1.06 | 4.16 | 0.80 | 1.07 | 4.19 | 0.80 | |||

| Age (18-34 as reference) | |||||||||

| 35-49 | 0.87 | 2.44 | 0.72 | 0.87 | 2.48 | 0.73 | |||

| 50-64 | -3.64 | 2.58 | 0.16 | -3.73 | 2.66 | 0.16 | |||

| 65+ | -5.96 | 8.45 | 0.48 | -5.90 | 8.61 | 0.49 | |||

| Immigrant (US-born as reference) | 1.22 | 2.62 | 0.64 | 1.14 | 2.65 | 0.67 | |||

| Education (less than 12 yrs as reference) 12 or more than 12 yrs | 2.22 | 2.12 | 0.30 | 2.21 | 2.19 | 0.31 | |||

| Employed (unemployment as reference) | -2.17 | 2.24 | 0.33 | -2.05 | 2.29 | 0.37 | |||

| Insurance Status (uninsured as reference) | |||||||||

| Private Only | 3.31 | 3.03 | 0.28 | 3.17 | 3.09 | 0.31 | |||

| Public Only | -0.22 | 2.20 | 0.92 | -0.13 | 2.26 | 0.95 | |||

| Other | 8.51 | 12.40 | 0.49 | 8.34 | 12.59 | 0.51 | |||

| Mental Health (good as reference) | |||||||||

| Excellent | -2.19 | 2.22 | 0.32 | -2.12 | 2.25 | 0.35 | |||

| Very Good | 6.96 | 3.06 | 0.02 | 7.08 | 3.11 | 0.02 | |||

| Fair | -4.83 | 2.88 | 0.09 | -4.81 | 2.90 | 0.10 | |||

| Poor | 4.36 | 5.19 | 0.40 | 4.30 | 5.24 | 0.41 | |||

| Disability Days | -0.28 | 0.10 | 0.01 | -0.27 | 0.10 | 0.01 | |||

| Diagnosis (depression as reference) | |||||||||

| Anxiety Disorder | 4.85 | 3.11 | 0.12 | 4.70 | 3.18 | 0.14 | |||

| Bipolar Disorder | 1.92 | 3.19 | 0.55 | 1.98 | 3.26 | 0.54 | |||

| Psychotic Disorder | 0.98 | 4.90 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 5.13 | 0.89 | |||

| Adjustment Disorder | -0.76 | 3.37 | 0.82 | -0.85 | 3.41 | 0.80 | |||

| Other | 3.13 | 2.93 | 0.29 | 3.19 | 2.96 | 0.28 | |||

| Attendance ratio during 180 days before baseline | 1.52 | 4.90 | 0.76 | ||||||

| Length in Treatment (months) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Constant | 19.81 | 11.04 | 0.07 | 21.06 | 12.59 | 0.09 | 20.02 | 13.15 | 0.13 |

Discussion

We have identified that patient-provider alliance on the tasks/goals of therapy, predicts greater prospective activation scores for patients in community-based mental health clinics above and beyond individual patient, clinical, and other relational factors. Our findings suggest that patients develop activation in the context of a working relationship with a provider. Implications of these findings support pursuing a more collaborative provider approach regarding the tasks/goals of treatment as means to achieve the goal of increasing patient activation.

Given that a strong therapeutic alliance hinges on patient and provider mutuality regarding treatment goals and how to achieve them, (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2003) our results regarding the task/goal factor suggest that patients in outpatient mental health care who effectively share treatment objectives with their providers will experience higher levels of patient activation. The findings that a therapeutic bond and strong communication are associated with activation at baseline (when entered into models separately), but not with greater change in PAM scores, suggest that strong communication and inter-dyadic bond may be prerequisites for activation early in the therapeutic relationship, but that alliance around tasks/goals of therapy instills in patients the sense that they are able to manage their mental health conditions over the long term. These findings align with a larger agenda in medical care promoting partnerships between patient and provider in clinical processes such as patient-centered care, shared decision-making, and patient-engaged care (Bernabeo & Holmboe, 2013; Carman et al., 2013).

To our knowledge this is the first study to suggest the causal direction of a patient-provider relational characteristic on activation. In previous studies the cross-sectional design limited the ability to discern whether provider interactions with patients led to greater patient activation or alternatively whether activated patients in some way altered provider behavior. Our results suggest that patient-provider relational factors contribute to greater patient activation in the context of an ongoing therapeutic relationship. However, even with a longitudinal design, we cannot assume causality. Because patient activation is likely influenced by the length and intensity of the therapeutic relationship, a more ideal study would have collected therapeutic alliance and activation measures at the beginning of the episode of mental health care rather than at varying stages in episodes of care. Though we have attempted to address these issues by controlling for visits attended prior to baseline and self-reported months in treatment, unobserved variables pertaining to the patient-provider relationship before the study period may still confound the relationship that we have identified in cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses.

An additional limitation is that because the PAM was introduced into the study protocol six months into the study, a portion of the participants did not complete this measure causing missingness on the outcome to be elevated. As a check on the validity of using only complete data, we estimated a model that included all data and accounted for missingness using multiple imputation methods. This sensitivity analysis yielded identical results as the analysis with complete data presented here, lending credence to our findings.

Despite study limitations, our results suggest that in addition to encouraging patients to become managers of their own health care, interventions should also improve provider contributions to patient activation by supporting providers to increase therapeutic alliance around the goals and tasks of therapy. While therapeutic alliance has been shown to be an important factor in mental health outcomes, and a key component in psychotherapy training, improving patient-provider therapeutic alliance has only infrequently been a focus of intervention studies (Bambling, King, Raue, Schweitzer, & Lambert, 2006; Crits-Christoph et al., 2006). However, results of these interventions and the broader literature suggest that improving therapeutic alliance is possible and results in improved outcomes. Much of the variation in therapeutic alliance has been identified as provider-specific and not attributable to patient characteristics, (Baldwin et al., 2007) and clear provider techniques (e.g. being supportive and respectful, noting past successes, and attending to the patient's experience) are known to be correlated with strong alliances (Hersoug, Hoglend, Havik, von der Lippe, & Monsen, 2009). These approaches and skills may be amenable to change, suggesting that interventions directed at improving providers' abilities to create a partnership with patients that fosters patients' activation are possible.

In sum, results of this study indicate that patients' ability to be active participants in their health care management is not solely an individual trait, but rather is determined in part by what happens within the patient-provider relationship. Specifically, we have identified that a working relationship where patients and providers are able to come to a common understanding on the tasks and goals of therapy, contributes to increased patient activation. Thus, to improve mental health outcomes it is important to expand efforts to increase patient activation to include a focus on providers. As strong as the call is for patients to change their self-management behaviors, the call for provider behavior change should be equally forceful.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Research Grant # P60 MD002261-03 funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. Authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose. The DECIDE intervention is based upon the educational strategy developed by the non-profit organization, the Right Question™ Institute (formerly, the Right Question Project). Since 1991, the Right Question Institute (www.rightquestion.org) has been developing and refining its innovative strategy for teaching question formulation and decision skills by learning from people in low-income communities around the country as they learned to advocate for their children's education, and advocated for themselves and their families in their ordinary encounters with social services, health care, housing agencies, job training and other programs. RIGHT QUESTION™, QUESTION FORMULATION TECHNIQUE™ and FRAMEWORK FOR ACCOUNTABLE DECISION-MAKING™ are trademarks owned by the Right Question Institute and are being used by the Cambridge Health Alliance with the Right Question Institute's permission. The Right Question Institute neither endorses nor is affiliated with this material and the associated research.

Footnotes

Early versions of this manuscript were presented at the American Public Health Association Meeting, November 5, 2013, Boston, MA; North American Primary Care Research Group national meeting, December 5, 2012, New Orleans, LA

References

- Ackerman SJ, Hilsenroth MJ. A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(1):1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Carson N, Flores M, Li X, Shi P, Lessios AS, et al. Shrout PE. Activation, self-management, engagement, and retention in behavioral health care: a randomized clinical trial of the DECIDE intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):557–565. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Polo A, Gao S, Santana L, Rothstein D, Jimenez A, et al. Normand SL. Evaluation of a patient activation and empowerment intervention in mental health care. Medical Care. 2008;46(3):247–256. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318158af52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Sribney W, Perez D, Laderman M, Keefe K. The role of patient activation on patient-provider communication and quality of care for US and foreign born Latino patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24 Suppl 3:534–541. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Hearld LR, Mittler JN, Harvey J. Patient-physician role relationships and patient activation among individuals with chronic illness. Health Services Research. 2012;47(3 Pt 1):1201–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrusyna TP, Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ, Luborsky L. The factor structure of the working alliance inventory in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research. 2001;10(3):173–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Wampold BE, Imel ZE. Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(6):842–852. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambling M, King R, Raue P, Schweitzer R, Lambert W. Clinical supervision: Its influence on client-rated working alliance and client symptom reduction in the brief treatment of major depression. Psychotherapy Research. 2006;16(3):317–331. doi: 10.1080/10503300500268524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi RP. Concept mapping the client's perspective on counseling alliance formation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):26–35. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabeo E, Holmboe ES. Patients, providers, and systems need to acquire a specific set of competencies to achieve truly patient-centered care. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):250–258. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, Sweeney J. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cegala DJ, Post DM. The impact of patients' participation on physicians' patient-centered communication. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, Inui TS. Delving below the surface. Understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21 Suppl 1:S21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MBC, Crits-Christoph K, Narducci J, Schamberger M, Gallop R. Can therapists be trained to improve their alliances? A preliminary study of alliance-fostering psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. 2006;16(3):268–281. doi: 10.1080/10503300500268557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PJ, Hibbard J, Gibbons CB. Raising Low ‘Patient Activation’ Rates Among Hispanic Immigrants May Equal Expanded Coverage In Reducing Access Disparities. Health Affairs. 2011;30(10):1888–1894. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen D, Lu WH, Rothstein D, Santana L, Gold MR. Asking questions: The effect of a brief intervention in community health centers on patient activation. Patient Education and Counseling. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghods BK, Roter DL, Ford DE, Larson S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-physician communication in the primary care visits of African Americans and whites with depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(5):600–606. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0539-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson WE, Curry KT, Bandalos DL. Reliability generalization of working alliance inventory scale scores. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2002;62(4):659–673. doi: 10.1177/001316402128775076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher RL, Barends AW. Patients' view of the alliance of psychotherapy: exploratory factor analysis of three alliance measures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(6):1326–1336. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersoug AG, Hoglend P, Havik O, von der Lippe A, Monsen J. Therapist characteristics influencing the quality of alliance in long-term psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2009;16(2):100–110. doi: 10.1002/cpp.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Greene J, Becker ER, Roblin D, Painter MW, Perez DJ, et al. Tusler M. Racial/ethnic disparities and consumer activation in health. Health Affairs. 2008;27(5):1442–1453. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Services Research. 2007;42(4):1443–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Services Research. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Services Research. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development of the Working Alliance Inventory. In: Horvath AO, Greenberg LS, editors. The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook. New York: Guilford; 1986. pp. 529–556. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SC, Boren D, Solem SL. The Kim Alliance Scale: development and preliminary testing. Clinical Nursing Research. 2001;10(3):314–331. doi: 10.1177/c10n3r7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan DM, Shaughnessy P. Analysis of the Development of the Working Alliance Using Hierarchical Linear Modeling. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(3):338–349. [Google Scholar]

- Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J, Sobel D, Remmers C, Bellows J. Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2007;30(1):21–29. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers C, Hibbard J, Mosen DM, Wagenfield M, Hoye RE, Jones C. Is patient activation associated with future health outcomes and healthcare utilization among patients with diabetes? Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2009;32(4):320–327. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ba6e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross EC, Polaschek DL, Wilson M. Shifting perspectives: a confirmatory factor analysis of the working alliance inventory (short form) with high-risk violent offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2011;55(8):1308–1323. doi: 10.1177/0306624X11384948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, Lipkin M, Jr, Stiles W, Inui TS. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1997;277(4):350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation for interval estimation from simple random samples with ignorable nonresponse. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1986;81(394):366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Institute SAS, I. SAS (Version 9.2) Cary, NC: USA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey TJ, Kokotovic AM. Factor Structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1:207–210. [Google Scholar]