Abstract

Objectives

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is associated with a higher risk for adverse health outcomes during pregnancy and delivery for both mothers and babies. This study aims to assess the short-term health and economic burden of GDM in China in 2015.

Design

Using TreeAge Pro, an analytical decision model was built to estimate the incremental costs and quality-of-life loss due to GDM, in comparison with pregnancy without GDM from the 28th gestational week until and including childbirth. The model was populated with probabilities and costs based on current literature, clinical guidelines, price lists and expert interviews. Deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the results.

Participants

Chinese population who gave birth in 2015.

Results

On average, the cost of a pregnancy with GDM was ¥6677.37 (in 2015 international $1929.87) more (+95%) than a pregnancy without GDM, due to additional expenses during both the pregnancy and delivery: ¥4421.49 for GDM diagnosis and treatment, ¥1340.94 (+26%) for the mother’s complications and ¥914.94 (+52%) for neonatal complications. In China, 16.5 million babies were born in 2015. Given a GDM prevalence of 17.5%, the number of pregnancies affected by GDM was estimated at 2.90 million in 2015. Therefore, the annual societal economic burden of GDM was estimated to be ¥19.36 billion (international $5.59 billion). Sensitivity analyses were used to confirm the robustness of the results. Incremental health losses were estimated to be approximately 260 000 quality-adjusted life years.

Conclusion

In China, the GDM economic burden is significant, even in the short-term perspective and deserves more attention and awareness. Our findings indicate a clear need to implement GDM prevention and treatment strategies at a national level in order to reduce the economic and health burden at both the population and individual levels.

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, health burden, economic burden, china

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to estimate the health and economic burden of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in China.

A conservative approach was adopted by including in the analyses only the most common GDM complications and the costs related to the last trimester of pregnancy.

We relied on different sources for probabilities and costs based on the literature and expert opinion rather than data from real cases.

We assumed that all pregnant women received standard medical treatments recommended in the Chinese GDM guidelines.

In order to extend our results to a national level, the costs of medical treatments obtained from the literature and the Chinese Price Bureaus were adjusted by calculating average unit prices taking into consideration the different expenses for different levels of healthcare institutions.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a health condition in which women without previously diagnosed diabetes exhibit high blood glucose levels during pregnancy.1 If not adequately managed, GDM may lead to serious adverse health outcomes during pregnancy and delivery,2 and in the long term as both mothers and newborn babies are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes mellitus, and babies are more likely to become obese later on in life.3 4

GDM affects 9.8%–25.5% of pregnancies throughout the world.5 The International Diabetes Federation estimates that 16.8% of pregnant women have some form of hyperglycaemia during pregnancy, with the majority (84%) due to GDM.6 According to a recent nationwide study in China that included 13 hospitals and 17 186 pregnant women,7 the GDM incidence rate was approximately 17.5%, based on the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria.5 In 2015, China’s population was approximately 1.37 billion people, and the annual pregnancy rate was 12.08 births per thousand individuals.8 9 Therefore, China had a total of 16.5 million pregnancies, and 2.90 million pregnant women suffered from GDM.

The aim of this study was to assess the short-term health and economic burden of GDM in China in 2015. Almost all of the GDM cases were diagnosed by the 28th gestational week; therefore, we estimated the incremental direct medical costs and the health loss due to GDM in comparison with a pregnancy without GDM from the 28th gestational week until childbirth. These differences in costs and health loss were then applied to the entire Chinese population to estimate the national burden of GDM. Neither postpartum nor longer term consequences (eg, eventual development of type 2 diabetes) were taken into consideration, as data were not available from the literature.

Methods

A model was built in TreeAge Pro 2015. Three submodels represented the cost of: (1) the GDM diagnosis and treatment (figure 1), (2) the maternal complications (figure 2) and (3) the neonatal complications (figure 3). Maternal and neonatal complications were selected according to published literature and expert opinions. Probabilities and costs related to each branch of the model were collected from the literature, clinical recommendations and price guidelines, and confirmed by a panel of hospital practitioners (gynaecologists, nutritionists, paediatricians and endocrinologist). Costs included expenses for outpatient physician visits, GDM screening, diet and exercise consulting, drugs, medical tests and supplies, and expenses for hospitalisation (eg, caesarean section and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission) and rehabilitation centre (eg, brachial plexus training).10 11 The unit prices of the GDM diagnosis and various medical treatments were obtained from the Chinese Price Bureaus in seven provinces representing seven regions of China: Northern China (Beijing), Eastern China (Zhejiang), Southern China (Guangdong), Central China (Hunan), Northwestern China (Shanxi), Southwestern China (Chongqing) and Tibet. An average unit price was calculated considering different expenses for the different levels of medical institutions (eg, township/second-class/third-class hospital).12 All the costs obtained from the literature were converted into 2015 prices according to inflation rates published by the China National Bureau of Statistics.13 Costs were not discounted, as the time horizon was shorter than 1 year. Finally, the results were applied at the national level to estimate the overall GDM burden. Deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted to confirm the robustness of results. Quality-of-life losses, expressed in quality-adjusted life years (QALY), were calculated to estimate the health burden caused by GDM for mothers; a QALY estimate was not possible for infants due to the lack of data. Given that human subjects were not directly involved, this study did not require approval by an institutional review board.

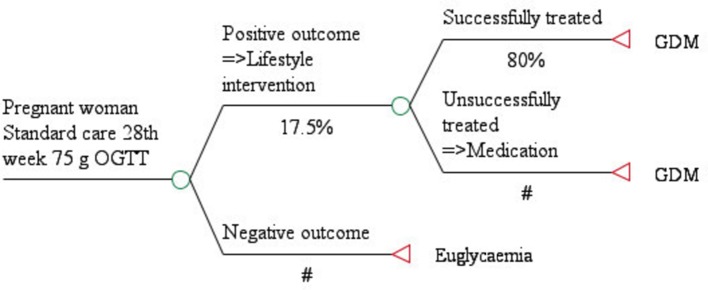

Figure 1.

GDM diagnosis and treatment model. This figure shows the generic framework of GDM screening path as recommended by Chinese guidelines. Circles represent chance events, while triangles represent terminal nodes. The symbol ‘#’ indicates that the probabilities of that branch are complementary with that of the other one. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

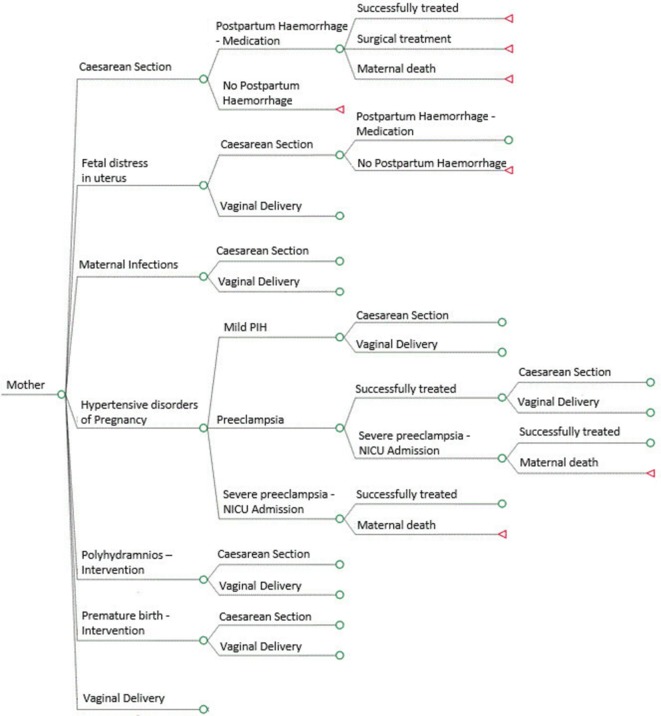

Figure 2.

Maternal complications model. This figure shows the mother complications model, which has the same structure for both gestational diabetes mellitus and Euglycaemia branches. The symbol ‘#’ indicates that the probabilities of that branch are complementary with that of the other one. Circles represent chance events, while triangles represent terminal nodes. Lines that do not terminate in a triangle are collapsed to facilitate display and are analogous to branches that are open.

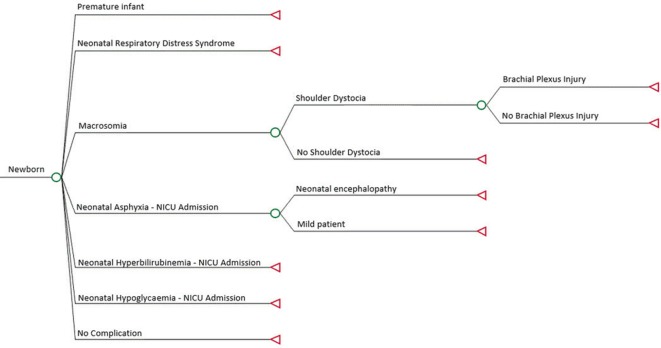

Figure 3.

Neonatal complications model. This figure shows the neonatal complications model, which has the same structure for both gestational diabetes mellitus and Euglycaemia branches. Circles represent chance events, while triangles represent terminal nodes.

Results

Diagnosis and treatment model

According to the most recent Chinese GDM guidelines,14 all women who have not been diagnosed with diabetes should take the 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between the 24th and 28th weeks of pregnancy. In our model (figure 1), for simplicity, we started from the 28th week. Women with negative OGTT tests entered the Euglycaemia branch, and those with positive OGTT test entered the GDM branch.

Women diagnosed with GDM in China first receive 1 week of lifestyle interventions (including diet, exercise and health education) and in 80% of cases the interventions successfully controlled blood glucose levels.15 When this was not enough (20% of cases), an additional insulin medication was prescribed.14 All of the pregnant women with a GDM diagnosis entered the GDM branch, independently from the way they controlled the disease (lifestyle interventions only or additional insulin).

The 80% of women who managed GDM with only lifestyle interventions until the end of their pregnancy spent on average ¥3118.14 per person; the 20% who relied on insulin to control their glucose level needed additional medications and examinations, for a total expense equal to ¥9875.74 per person (table 1).

Table 1.

Input parameters: probabilities and costs (¥)

| Diagnosis and treatment model12 | |||||||

| Resource | Frequency of consumption | Unitary cost | Total costs | ||||

| Euglycaemia | Lifestyle intervention | Insulin | Euglycaemia (week 28) | Lifestyle interventions (week 28–40) | Insulin (weeks 28–40; insulin costs from week 30) |

||

| Oral glucose tolerance test | Once | Once a week | Once a week | 35.43 | 35.43 | 425.16 | 425.16 |

| Venous blood collection | Once | Once a week | Once a week | 2.4 | 2.4 | 28.8 | 28.8 |

| Obstetric and gynaecologist outpatient registration fee | Once | Once a week | Once a week | 1.91 | 1.91 | 22.92 | 22.92 |

| Examination fee | Once | Once the first week+three times a week | Once the first week+three times a week | 8.43 | 8.43 | 286.62 | 286.62 |

| First consultation fee | Once | Once | 23 | 23 | 23 | ||

| Nutrition outpatient registration fee | Twice a week | Twice a week | 1.91 | 45.84 | 45.84 | ||

| Glucometer and self-testing kit | Yes | Yes | Monitor=190, strips=5 each | 730 | 730 | ||

| Laboratory fees (urine, glycosylated albumin) | Once a week | Once a week | 70.79 | 849.48 | 849.48 | ||

| Fetal heart and B ultrasound | Once a week | Once a week | 58.86 | 706.32 | 706.32 | ||

| Routine blood test | Once a week | 20.75 | 207.5 | ||||

| Insulin shot | Three times a day | 30 | 6300 | ||||

| Endocrinology outpatient registration fee | Once a week | 1.91 | 19.1 | ||||

| Doppler ultrasound | Twice | 115.5 | 231 | ||||

| Total | 48.17 | 3118.14 | 9875.74 | ||||

| Maternal complications model—probabilities and costs | |||||||

| Complication | GDM (%) | % | Euglycaemia (%) | Difference (%) | Complication Cost | Reference | |

| Caesarean section | 38.64 | 30.3 | 8.34 | 6174 | 35–40 | ||

| Fetal distress in uterus | 9.26 | 6.48 | 2.78 | 3994 | 36 | ||

| Maternal infection | 5.67 | 2.7 | 2.97 | 512.01 | 41 | ||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 10.63 | 7.11 | 3.52 | 35–40 | |||

| Mild PIH | 84.2 | 53 | |||||

| Pre-eclampsia | 15.7 | ||||||

| Successfully treated | 99.9 | 6762 | |||||

| Severe pre-eclampsia | 0.1 | ||||||

| Successfully treated | 99.99 | 8939 | |||||

| Maternal death | 0.01 | 8939 | |||||

| Polyhydramnios | 9.83 | 3.78 | 6.04 | 3994 | 35–40 | ||

| Postpartum haemorrhage | 8.32 | 4.28 | 4.04 | 35–40 | |||

| Successfully treated | 99.75 | 7610 | |||||

| Surgical treatment | 0.24 | 15 939 | |||||

| Maternal death | 0.01 | 8939 | |||||

| Premature birth | 6.35 | 2.47 | 3.88 | 2943 | 35–40 | ||

| Neonatal complications model—probabilities and costs | |||||||

| Neonatal complication | GDM (%) | Euglycaemia (%) | Difference (%) | Complication Cost | Reference | ||

| Premature infant (NICU) | 6.35 | 2.47 | 3.88 | 2536 | 35–40 | ||

| Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (NICU) | 5.9 | 4.03 | 1.87 | 32 480 | 35–40 | ||

| Macrosomia | 8.7 | 6.31 | 2.39 | 3675.56 | 36–40 | ||

| Shoulder dystocia | 14.5 | 3578 | |||||

| Brachial plexus injury | – | 18 | 7316 | ||||

| Neonatal asphyxia (NICU) | 3.78 | 1.27 | 2.52 | 6652.44 | 36 | ||

| Mild | 53 | 6064 | |||||

| Neonatal encephalopathy | 47 | 7316 | |||||

| Neonatal hypoglycaemia (NICU) | 6 | 0.86 | 5.14 | 3578 | 42 | ||

| Neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia NICU | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 3504 | 39 | ||

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Summing these costs, weighted for the types of treatments provided (80% lifestyle interventions only, 20% additional insulin), the costs of diagnosis and treatment was equal to ¥4469.66 per GDM case. The costs of diagnosis and treatment for Euglycaemia, which included the OGTT and other recommended visits regardless of GDM status, were equal to ¥48.17. Therefore, the extra burden due to GDM for diagnosis and treatment was equal to the difference between GDM and Euglycaemia women (¥4421.49 per case).

Maternal complications model

Maternal complications included in the model are represented in figure 2. The costs and probabilities associated with the adverse health outcomes are listed in table 1. Due to the lack of data on probabilities of the two types of delivery (vaginal or caesarean section) after different complications (eg, fetal distress in uterus), we assumed all branches as independent events ending up with the same probabilities of facing either a caesarean section or a vaginal delivery. The difference was only by GDM status (eg, caesarean section 38% in case of GDM, 30.3% in case of Euglycaemia).

The cost assigned to vaginal delivery was equal to ¥3275.39.16 All births following the possible complications were classified as vaginal or caesarean section; however, a caesarean section was considered an additional complication independent of complications prior to birth. The probability of not having any complication was obtained by subtracting the sum of the other probabilities from 1. The costs of maternal complications were on average ¥5253.57 in Euglycaemia cases and ¥6594.51 in GDM cases, with a cost difference of ¥1340.94 (+26%).

Neonatal complications model

Neonatal complications are represented in figure 3. A few rare neonatal complications (ie, abnormal fetus) were excluded, as cost data were not available from the literature. We did not include macrosomia, one of the most common consequences of GDM, because we could not determine a direct medical cost for it, but only for its consequences (eg, brachial plexus injury).

Related costs and probabilities of the adverse health outcomes are listed in table 1. The probabilities of having a newborn with and without complications summed to 100%. Costs were not assigned to newborns without complications, on the assumption that this should be included in the mother’s normal delivery expenses.

The costs of neonatal complications were on average ¥1755.57 in Euglycaemia cases and ¥2670.51 in GDM cases, resulting in a cost difference of ¥914.94 (+52%).

Overall costs

On average, women with GDM spent ¥6677.37 (equal to 2015 international $1929.87 (1 international $=¥3.46)17 more (+95%) than women without GDM, due to additional expenses during both pregnancy and delivery.

Therefore, given the 2.90 million women affected by GDM in China, the annual economic burden of GDM in 2015 equalled ¥19.36 billion (international $5.59 billion).

Sensitivity analyses

In order to quantify the uncertainty, we performed both a deterministic analysis and a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. In the deterministic sensitivity analysis (tornado diagrams, online supplementary appendix figure 1), we applied a ±20% variation to all costs and major probabilities of each submodel to determine which input variables had the largest impact on the outcomes and thereby had a large impact on the overall results. The variables with the largest impact on the final costs were insulin in the diagnosis and treatment model, caesarean section in the maternal complications model and respiratory distress syndrome, which included admission to the intensive care unit, in the neonatal complications model. The variation of all the other costs had a minor impact on the final outcomes.

bmjopen-2017-018893supp001.jpg (157.1KB, jpg)

In the probabilistic sensitivity analysis (Monte Carlo simulation, online supplementary appendix figure 2) for the maternal and neonatal complications models, we applied a ±20% variation to all costs, modelled using a gamma distribution.18 The possible outcomes of the simulation ranged around the results from the base case; the overall results were shown to be robust.

bmjopen-2017-018893supp002.jpg (143.8KB, jpg)

Utilities

In addition to the costs, we also calculated the health-related quality-of-life loss due to GDM (table 2).

Table 2.

Gestational diabetes mellitus-related health loss

| Health outcome | Quality adjusted-life years (1 year) | Reference | Health loss (3 months) | Probability (%) | Women (n) | Total health loss (3 months) |

| Maternal diabetes | 0.65 | 43 | 0.0875 | 17.5 | 2 887 500 | 252 656 |

| Insulin injection | 0.96 | 44 | 0.01 | 0.2×17.5 | 577 500 | 5775 |

| Preterm birth | 0.99 | 43 | 0.0025 | 0.0388× 17.5 | 112 035 | 280 |

| Caesarean section | 0.99 | 45 | 0.0025 | 0.0861×17.5 | 248 613.75 | 621 |

| Hypertensive disorders | 0.9625 | 46 | 0.0094 | 0.0352×17.5 | 101 640 | 953 |

| Total | 260 285 |

Given the lack of published studies with neonatal utilities in China, we considered only mother-related events. Each adverse health event had a utility value expressed in QALY (eg, 0.65 QALY in case of maternal diabetes). We calculated the difference between this value and 1 QALY, which corresponds to the full health status (following the example of maternal diabetes, 1–0.65=0.35 QALY). Since QALYs were based on 1 year, we divided this amount by 4 to take into consideration the health loss of only 3 months. This was the time horizon in this study (0.35/4=0.0875 QALY). We then multiplied the 3-month health loss with the appropriate probabilities of occurrence corresponding to the entire population suffering from GDM (2.9 million women) in the case of ‘maternal diabetes’, 20% of those (577 000 women) in the case of ‘insulin injection’ and the number of women with GDM weighted by the difference in probability between GDM and non-GDM for ‘preterm birth’, ‘caesarean section’ and ‘hypertensive disorders,’ on the assumption that these adverse health events may occur even in non-GDM pregnancies. For example, the probability of having a preterm birth was 6.35% for GDM women and 3.47% for non-GDM women (3.88% difference). Therefore, the preterm birth health loss due to GDM was calculated as 0.0025 QALY (3-month health loss) multiplied by 112 000 women (2.9 million×3.88%). The total incremental health loss due to GDM in China was equal to 260 000 QALYs.

Discussion

GDM prevalence is increasing worldwide with serious consequences for mothers and their babies.2 The importance of GDM as a priority for maternal health and its impact in the long term for communicable diseases has been established; however, a consensus on how to prevent, diagnose and manage GDM in order to optimise healthcare and minimise adverse outcomes has not been reached.19 For example, although IADPSG criteria are internationally well accepted and adopted by some Asian countries, they are not consistently implemented, especially in low-resource settings20; therefore; having harmonised data to compare studies from different countries remains a challenge.

Principal findings

To our best knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the economic burden of GDM in China. More at-risk births are expected in the near future due to the increasing prevalence of overweight/obese women and older age at pregnancy in China.21 Moreover, in early 2016, the Chinese government officialised the end of the one-child policy; therefore, prevalence of GDM cases are likely to increase given that a previous pregnancy with GDM is a well-established risk factor for GDM in subsequent pregnancies.6 22 Adding an economic point of view to the GDM burden estimation may help to increase social awareness and to develop national health policies. The cost analysis showed that the economic burden of gestational diabetes in pregnancy may be substantial, even when limiting the analysis to only short-term effects. According to our findings, the total burden due to GDM in 2015 was estimated at ¥19.36 billion (international $5.59 billion), which is equal to 0.5% of the entire public expenditure for medical, healthcare and family planning in China in 2015.23 GDM lifestyle interventions, including diet, exercise and health education, were very effective. In 80% of cases, interventions were shown to significantly reduce GDM complications and their final costs, and only 20% of women with GDM needed additional medications.15 24 However, the costs among the 20% of women with GDM requiring additional medications were more than three times higher (¥3118.14 vs ¥9875.74), due to the price of insulin, which had the greatest impact on the final cost of diagnosis and treatment.

Finally, due to different GDM-associated adverse events during both pregnancy and delivery, when only accounting for maternal consequences, around 260 000 QALYs were lost over a 3-month period. To quantify the magnitude of this loss, the health loss due to GDM was about 1/4 of 1 180 260 QALYs loss caused by squamous cell carcinoma (one lung cancer type) or 1/18 of QALYs loss caused by all types of lung cancers in China.25 26

Comparison with other studies

Our study was based on the Chinese healthcare system. Studies from Australia,27 Finland28 and the USA3 reported that the mean difference in healthcare costs between a normal pregnancy and women diagnosed with GDM is about $462.02 ($A650), $1438 (€1289) and $15 593; respectively; however, comparing these findings from high-income countries with this study in China might not be straightforward considering the different nature of healthcare systems between countries.

Strengths and weaknesses

A strength of this study was the conservative approach we adopted. For simplicity, we only included costs from after the 28th week of pregnancy, but GDM could be diagnosed at the 24th week or even earlier in severe cases.29 Moreover, minor GDM complications, such as abnormal fetus or hyaline membrane disease, were excluded as there were no clinical studies to provide probabilities and costs in China. Furthermore, we did not include the price of food substitutions in case of a change in diet to control GDM. Finally, we considered only insulin as a drug cost, disregarding other medications that might be prescribed.

The first limitation of this study was that we relied on several different sources for probabilities and costs. Some of those were based on local literature and confirmed by expert panels; however, experts might rely on personal experiences. Second, due to the lack of data in the maternal model we assumed the same probabilities of having a caesarean section or a vaginal delivery after every event, differentiating only by GDM status, while in a real-life setting this would not be the case (eg, caesarean section might be more likely than vaginal delivery in case of fetal distress in uterus). Nevertheless, several scenario analyses with different probabilities confirmed that there was not a major impact on the final outcome.

Third, we assumed that all women followed exactly the clinical pathways and were fully compliant, which might not always be the case. However, it could be assumed that non-compliant behaviour would increase the health and economic burden of GDM as the health consequences of uncontrolled GDM were higher. Finally, we could not estimate the percentage of out-of-pocket expenses that were paid by each individual mother.

Public health implications

In China, maternity insurance to cover expenses during pregnancy and delivery is not included in regular health insurance and is only used by employed women.30 31 Unemployed women living in rural areas are covered by the subsidies of the newly cooperative medicine scheme (NCMS). The purpose of these subsidies is the same as the maternity insurance: to provide basic economic and health aids to pregnant women. Both maternity insurance and subsidies reimburse a lump sum amount per pregnancy and delivery (vaginal delivery or caesarean section). Unfortunately, there are huge variations between the two types of coverage and, in general, for the specific amounts received within the country, the maternity insurance normally pays approximately ¥3000, while subsidies from NCMS in the rural areas are approximately ¥500–1000.30 31 However, in both cases, the actual pregnancy and delivery expenses are much more than the amount covered by maternity insurances or subsidies. GDM is not reimbursed separately by any insurance or subsidies, so a large portion of the GDM burden falls on women and their families. According to You et al,32 60% of the cost of deliveries in China were paid out of pocket, a share that did not significantly change after the introduction of the insurance system. This is even worse for the low-income group where, given an average income equal to ¥4747,33 paying ¥10965 for GDM antenatal and delivery cost is not sustainable and could enter the area of the catastrophic healthcare expenditure.34

Unanswered questions and future research

In China, the increase of GDM incidence has led to significant economic burden and deserves more attention and awareness. Our study showed the magnitude of the problem, and cost-effective GDM prevention treatments are needed to reduce GDM morbidities, complications from GDM and the consequent economic burden that affects society, households and individuals in China.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Sheri Volger (King of Prussia, Nestlé SA, Pennsylvania, USA) for her suggestions and critical comments, which deeply helped us to improve the study. Moreover, we thank Dr Maria Laura Gosoniu (Nestlé Research Center, Lausanne, Switzerland) for her statistical advices and Dr Kevin Mathias (Nestlé Research Center, Lausanne, Switzerland) and Janet Matope (Nestlé Research Center, Lausanne, Switzerland) for the language revision.

Footnotes

TX and LD contributed equally.

Contributors: PD, ISZ and HF conceived this study. TX and LD designed it, with input from other coauthors. TX and HF were involved in the design and were responsible for the data collection. TX and LD completed the analyses presented here. LM provided independent clinical advice. TX and HF wrote the first draft of the paper with further iterations involving LD. KY contributed to the interpretation of the data and the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed, reviewed and approved the final submitted version.

Funding: This work was funded by Nestlé Research Center (Lausanne, Switzerland).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2011;34:62–9. 10.2337/dc11-S062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, et al. Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS) Trial Group. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2477–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lenoir-Wijnkoop I, van der Beek EM, Garssen J, et al. Health economic modeling to assess short-term costs of maternal overweight, gestational diabetes, and related macrosomia - a pilot evaluation. Front Pharmacol 2015;6:103 10.3389/fphar.2015.00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verier-Mine O. Outcomes in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Screening and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Literature review. Diabetes Metab 2010;36:595–616. 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:e98–82. 10.2337/dc10-0719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131:S173–S211. 10.1016/S0020-7292(15)30033-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu WW, Yang HX, Wei YM, et al. Evaluation of the value of fasting plasma glucose in the first prenatal visit to diagnose gestational diabetes mellitus in china. Diabetes Care 2013;36:586–90. 10.2337/dc12-1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Purple Culture. China Health and Family Planning Statistical Yearbook. China: Peking Union Medical College Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. China National Health and Family Planning Commission. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the PRC. 2015.

- 10. Rao L, Xia S. Analysis of the hospitalization expenses of different delivery methods in the non cesarean section delivery mode. Chinese Health Resources 2013;06:392–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu S, Lai R, Jin Y, et al. Analysis of the structural characteristics and trend of the hospitalization expenses of the common diseases of the newborn. Chinese Health Economics 2008;07:27–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chinese Price Bureaus. Basic Medical Service Prices in 7 provinces (Beijing, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Hunan, Shanxi, Chongqing, Tibet, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. China Health Statistics Yearbook: China Statistics Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang H, Xu X, Wang Z, et al. A guide for the diagnosis and treatment of pregnancy complicated with diabetes. Diabetic World 2014;11:489–98. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li L, Yan T, Liu J, et al. The diet and exercise intervention on patients with gestational diabetes blood sugar control. West China Medical Journal 2014;11:2069–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16. He Z, Cheng Z, Wu T, et al. The costs and their determinant of cesarean section and vaginal delivery: an exploratory study in chongqing municipality, China. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:1–9. 10.1155/2016/5685261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The World Bank. PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $). 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP?locations=CN&name_desc=true (accessed on Dec 2016).

- 18. Tengs TO, Wallace A. One thousand health-related quality-of-life estimates. Med Care 2000;38:583–637. 10.1097/00005650-200006000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hod M, Jovanovic LG, Di Renzo GC, et al. Textbook of diabetes and pregnancy: CRC Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tutino GE, Tam WH, Yang X, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: perspectives from Asia. Diabet Med 2014;31:302–18. 10.1111/dme.12396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leng J, Shao P, Zhang C, et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in Chinese pregnant women: a prospective population-based study in Tianjin, China. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121029 10.1371/journal.pone.0121029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MacNeill S, Dodds L, Hamilton DC, et al. Rates and risk factors for recurrence of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001;24:659–62. 10.2337/diacare.24.4.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Bureau of Statistics of China. China statistical yearbook 2015. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2015/indexeh.htm (accessed on 4 Jan 2017).

- 24. Xu T, He Y, Dainelli L, et al. Healthcare interventions for the prevention and control of gestational diabetes mellitus in China: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:171 10.1186/s12884-017-1353-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang XL. Investigating the epidemiological characteristics of lung cancer in China and estimating the morbidity and mortality. World News Digest of latest medical information 2016;16:330–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang SC, Lai WW, Su WC, et al. Estimating the lifelong health impact and financial burdens of different types of lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2013;13:579 10.1186/1471-2407-13-579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moss JR, Crowther CA, Hiller JE, et al. Costs and consequences of treatment for mild gestational diabetes mellitus - evaluation from the ACHOIS randomised trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2007;7:27 10.1186/1471-2393-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kolu P, Raitanen J, Rissanen P, et al. Health care costs associated with gestational diabetes mellitus among high-risk women--results from a randomised trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:71 10.1186/1471-2393-12-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boriboonhirunsarn D, Sunsaneevithayakul P, Nuchangrid M. Incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed before 20 weeks of gestation. J Med Assoc Thai 2004;87:1017–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tan C, Zhang Y. The evolution of China’s maternity insurance system and government responsibility. China Soft Science 2011;08:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ban X. Maternity insurance system in rural areas Chinese. Journal of Shangdong Woman University 2012;01:25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. You H, Gu H, Ning W, et al. Comparing maternal services utilization and expense reimbursement before and after the adjustment of the new rural cooperative medical scheme policy in rural China. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158473 10.1371/journal.pone.0158473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Bureau of Statistics. China’s economy realized a new normal of stable growth in 2014. 2015. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/201501/t20150120_671038.html (accessed on 6 Oct 2016).

- 34. Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, et al. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet 2003;362:111–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu G, Fan X, Chen S. Analysis of the effect of standardized treatment on the outcome of pregnancy in women with gestational diabetes. Journal of Community Medicine 2008;6:21–2. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hao S, Du C, Chao Y, et al. Influence of standardized treatment on pregnancy outcome of gestational diabetes [J]. Journal of Qiqihar Medical College 2011;13:2137–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang X, Chen H, Weng J. The effect of standardized treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus. China Healthcare Innovation 2009;04. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lily T, Zhao Y, Zhang A, et al. Effect of standardized management of gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy outcome. General Nursing Care 2011;09:763–4. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu X, Zhou T, Zhang H, et al. Standardized management of gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcome. Chinese Maternal and Child Health care 2011;26:180–2. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fang H, Wang C, Zhao H. Effect of standardized treatment of pregnancy with diabetes on pregnancy outcome. Modern Medical Journal 2007;23:2576–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yi Y, Pan H, Chen L, et al. The effect of comprehensive nursing on the pregnancy outcome of 34 cases of gestational diabetes mellitus (J). Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacology 2015;13:122–3. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fangmin XJ, Xu X. Pregnancy with glucose metabolism abnormalities and neonatal hypoglycemia. China Medical Engineering 2007;05:401 403. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Werner EF, Pettker CM, Zuckerwise L, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: are the criteria proposed by the international association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups cost-effective? Diabetes Care 2012;35:529–35. 10.2337/dc11-1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Scuffham P, Carr L. The cost-effectiveness of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion compared with multiple daily injections for the management of diabetes. Diabet Med 2003;20:586–93. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ohno MS, Sparks TN, Cheng YW, et al. Treating mild gestational diabetes mellitus: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:282.e1–282.e7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sonnenberg FA, Burkman RT, Hagerty CG, et al. Costs and net health effects of contraceptive methods. Contraception 2004;69:447–59. 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018893supp001.jpg (157.1KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-018893supp002.jpg (143.8KB, jpg)