Abstract

Objectives

The policy of centralising hyperacute stroke units (HASUs) in England aims to provide stroke care in units that are both large enough to sustain expertise (>600 admissions/year) and dispersed enough to rapidly deliver time-critical treatments (<30 min maximum travel time). Currently, just over half (56%) of patients with stroke access care in such a unit. We sought to model national configurations of HASUs that would optimise both institutional size and geographical access to stroke care, to maximise the population benefit from the centralisation of stroke care.

Design

Modelling of the effect of the national reconfiguration of stroke services. Optimal solutions were identified using a heuristic genetic algorithm.

Setting

127 acute stroke services in England, serving a population of 54 million people.

Participants

238 887 emergency admissions with acute stroke over a 3-year period (2013–2015).

Intervention

Modelled reconfigurations of HASUs optimised for institutional size and geographical access.

Main outcome measure

Travel distances and times to HASUs, proportion of patients attending a HASU with at least 600 admissions per year, and minimum and maximum HASU admissions.

Results

Solutions were identified with 75–85 HASUs with annual stroke admissions in the range of 600–2000, which achieve up to 82% of patients attending a stroke unit within 30 min estimated travel time (with at least 95% and 98% of the patients being within 45 and 60 min travel time, respectively).

Conclusions

The reconfiguration of hyperacute stroke services in England could lead to all patients being treated in a HASU with between 600 and 2000 admissions per year. However, the proportion of patients within 30 min of a HASU would fall from over 90% to 80%–82%.

Keywords: stroke, organisation of health services, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study described allows for a national view of the relationship between the number of acute stroke units (based on choosing from current locations of acute stroke units) in England and the dual goals of (1) having all patients attend a stroke unit with at least 600 acute confirmed stroke admissions per year, and (2) having patients within 30 min of an acute stroke unit.

The study uses a genetic algorithm that is able to hunt for solutions when there is a vast range of possibilities.

The study takes an objective approach with explicitly described objectives.

A limitation of the study is that identified solutions do not take into account the complex local pressures and reasons for preferring one unit over another at the cost of the objectives used in identifying solutions in this study.

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide, with an estimated 5.9 million deaths and 33 million stroke survivors in 2010.1 In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 85 000 people are hospitalised with stroke each year,2 and stroke is ranked third as a cause of loss of disability-adjusted life years in the UK over the last 25 years.3

In recent years the National Health Service (NHS) in England has sought to promote the reconfiguration of stroke services across the country, building on the evidence-based model developed in London.4 Centralisation of stroke care in London has been shown to increase thrombolysis rates, reduce mortality, reduce length of stay and reduce long-term costs to the NHS.5 6 These benefits are considered to be due to patients being cared for by specialist stroke teams, facilitated by direct hospital admission to a large hyperacute stroke unit (HASU). In the HASU model of care, patients are taken directly to units that may provide immediate response to stroke, including assessment, stabilisation and any primary intervention, before later discharge or transfer to step-down local stroke units.7 Guidelines recommend a minimum number of admissions to a HASU of 600 patients per year, and NHS England reconfiguration guidelines also suggest ‘travel time should be ideally 30 min but no more than 60 min’.8 9 Centralisation of acute stroke care in London was guided by a modelling exercise whereby sites were identified with no Londoner more than a 30 min ambulance journey from the nearest HASU.5 Time from onset to emergency hospital treatment is known to be especially critical for ischaemic stroke, when the effectiveness of thrombolysis declines rapidly in the first few hours after stroke.10 More recently, mechanical thrombectomy has shown effectiveness in patients presenting up to 6 hours after stroke onset, with effectiveness still higher if treatment is given earlier.11

With the critical importance of speed to treatment with thrombolysis or thrombectomy, it has nonetheless been questioned if the improvements in outcome that came with centralisation of stroke services in metropolitan areas could be replicated in more rural environments, with modelling being suggested as a first step at analysing the problem.12 We therefore sought to investigate the potential for meeting the dual objectives of all patients with acute stroke being admitted to a HASU of sufficient size (at least 600 patients with acute stroke per year) and that unit being within 30 min travel time. The modelling described here focuses on the HASU phase of stroke care7 and does not extend to organisation of ongoing step-down care in local stroke units, or after discharge home.

Methods

Detailed methods, with links to underlying data and source code used, are given in the online supplementary appendix.

bmjopen-2017-018143supp001.pdf (122.8KB, pdf)

The model predicts, for any configuration of HASUs, the travel times (fastest road travel time chosen, from home location of patient to hospital with the shortest estimated travel time) and the number of admissions to each HASU. A genetic algorithm was used to identify good configurations.

We included 238 887 patients coded with ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke (ICD-10 I61, I63, I64; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) with an emergency admission over a 3-year period (2013–2015). Stroke admission numbers were counts of admissions for each of 31 771 Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) in England. No individual patient-level data were accessed: counts of admissions per LSOA were extracted from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES; http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes), with access to national HES data managed through Lightfoot Solutions (http://www.lightfootsolutions.com/). Estimated fastest road travel times were obtained from a geographical information system (Maptitude, with MP-MileCharter add-in).

We used a genetic algorithm based on NSGA-II (Nondominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm)13 to derive potential configurations of HASUs across England, balancing competing objectives. Solutions were eliminated if another solution was equally as good in all optimisation parameters and was better in at least one parameter. The selected configurations were based on a range of optimisation parameters (listed in the online supplementary appendix) that seek to minimise travel distances and to control admission numbers (admitting as many people to HASUs with at least 600 admissions per year while also seeking to control the maximum number of admissions to any hospital). Solutions retained are referred to as non-dominated solutions; together these form a ‘Pareto front’, where improved performance in one objective can only be at the expense of another.

Results

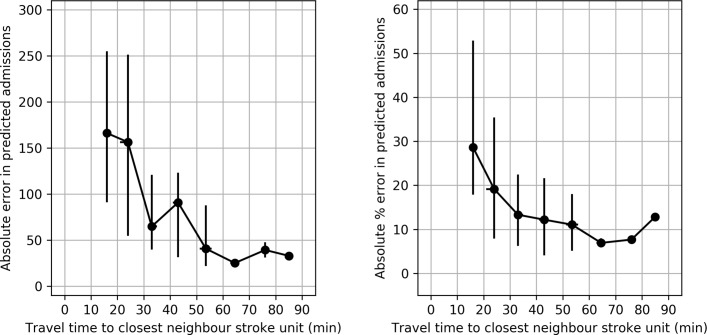

The model assumes patients attend the hospital closest to their home location. In order to test this assumption, we compared admissions predicted (assuming that patients attend their closest hospital) with actual admissions to each hospital. When comparing predicted with actual admissions, there was a median absolute error of 105 admissions per unit per year, or a relative absolute error of 17%. Prediction accuracy depended on proximity to a hospital’s nearest neighbour, and was proportionately greater in urban areas where travel distance is less of a consideration. HASUs located close to other acutely admitting units have a poorer prediction accuracy than those located further from the nearest alternative acute stroke unit (figure 1). These results gave confidence in progressing with the basic model assumption that patients should generally attend their closest unit.

Figure 1.

Error in predicting admissions (as recorded in Sentinel Stroke Audit Programme) grouped by proximity to the closest neighbouring acute stroke unit (10 min bins). Points show median, with error bars indicating IQR. The left panel shows the absolute error in predicting admission numbers per year, while the right panel shows the absolute error as a percentage of actual admissions for each unit.

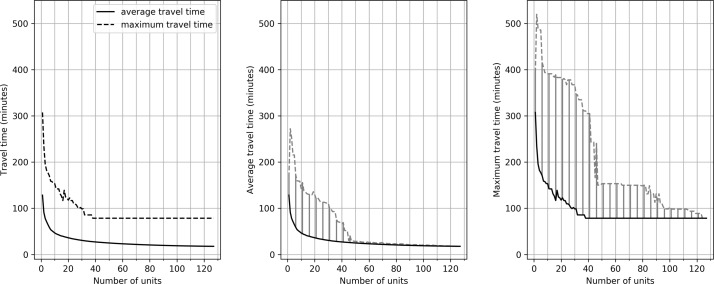

With an increasing number of HASUs, average and maximum road travel times reduce (figure 2), following the law of ‘diminishing returns’. For example, with 24 units (the number of neuroscience centres in England) the lowest average travel time is 34 min. As the number of HASUs is increased to 50, 75 and 100, the best average travel times found are 26, 22 and 19 min, respectively. The best maximum travel times found are 109, 99, 78 and 78 min with 25, 50, 75 and 100 HASUs. Average and maximum travel times for the identified solutions depend on what other factors are prioritised in the model. For example, with 25 HASUs, the average travel distances in different configurations (all of which are non-dominated solutions) range from 34 to 62 min, and the maximum travel time range from 109 to 378 min.

Figure 2.

The effect of changing the number of acute stroke units on average and maximum travel times. The left panel shows the best average and maximum travel times achieved by the algorithm. The middle panel shows the average travel times. The bold line represents the best result identified in any scenario. The dotted line shows the worst result identified for a non-dominated solution. The shaded area represents the effective region of trade-off between average travel time and other optimisation parameters. The right panel repeats these results for maximum travel time.

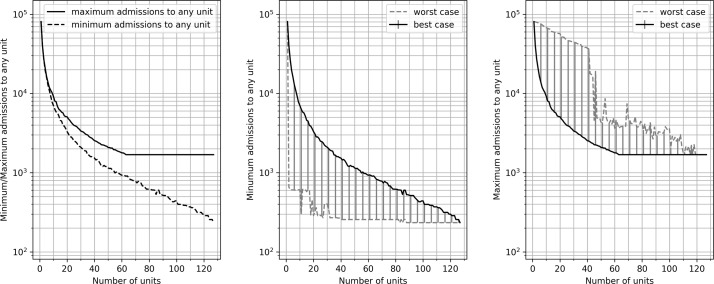

As the number of HASUs increases, both the maximum and minimum numbers of admissions to any single hospital in the configuration reduce (figure 3). For example, with 25 units the lowest possible maximum number of admissions to any single unit is 4381 admissions per year. With 50, 75 and 100 units, the largest hospital has admissions of 2493, 1829 and 1687 patients per year. These results represent the best compromise between unit size and distance if no other factors are regarded as important. To achieve all admissions attending a HASU with at least 600 admissions per year, the maximum number of hospitals is 85, by which point 82% of the population is within 30 min travel (with 95% and 98% being within 45 and 60 min, and the maximum travel time is 99 min).

Figure 3.

The effect of changing the number of acute stroke units on minimum and maximum admissions to any single unit. The left panel shows the best admissions identified by the algorithm (it is better to have a higher minimum number of admissions and lower maximum admissions; that is, the smallest hospital should be as large as possible, and the largest hospital as small as possible). The middle panel shows minimum admission numbers (to the smallest unit in each scenario). The bold line represents the best result identified in any scenario. The dotted line shows the worst result identified for a non-dominated solution. The shaded area represents the effective region of trade-off between average minimum admissions and other optimisation parameters. The right panel repeats these results for maximum admissions in a scenario.

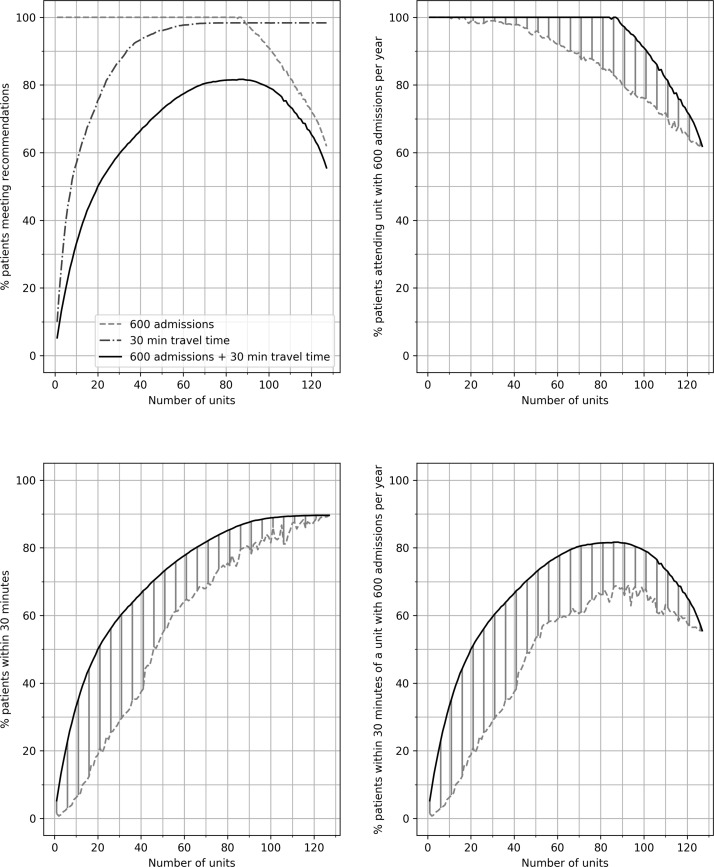

As the number of HASUs increases, the proportion of patients within 30 min travel increases (figure 4), to a maximum of 90% (the best possible proportions with 25, 50, 75 and 100 units were 52%, 70%, 84% and 88%). At the same time, increasing the number of HASUs reduces the number of patients attending a unit with at least 600 admissions per year (figure 4). Increasing the number of units leads first to an increase in the proportion of patients attending a unit of sufficient size within 30 min travel, but when increased further a reduction in this proportion is seen (figure 4). The maximum proportion of patients attending a unit admitting 600 patients per year within 30 min travel is 82%. Solutions with at least 80% of patients being within 30 min of a HASU admitting at least 600 patients per year have between 75 and 95 HASUs. If target travel time is increased from 30 min to 45 min, then the maximum proportion of patients attending a HASU of sufficient size is 95%, with this maximum occurring with between 65 and 90 units.

Figure 4.

The effect of changing the number of acute stroke units on the proportion of patients attending a unit with 600 admissions per year, the proportion of patients attending a unit within 30 min of home location and the proportion of patients attending a unit with 600 admissions per year and within 30 min of home location. The top left panel shows the best solutions for each identified by the algorithms. The top right panels shows the proportion of patients attending a unit with 600 admissions per year. The bold line represents the best result identified in any scenario. The dotted line shows the worst result identified for a non-dominated solution. The shaded area represents the effective region of trade-off between attending a unit with target admission numbers and other optimisation parameters. The bottom two panels repeat the analysis for the proportion of patients attending a unit within 30 min of home location and the proportion of patients attending a unit with 600 admissions per year and within 30 min of home location.

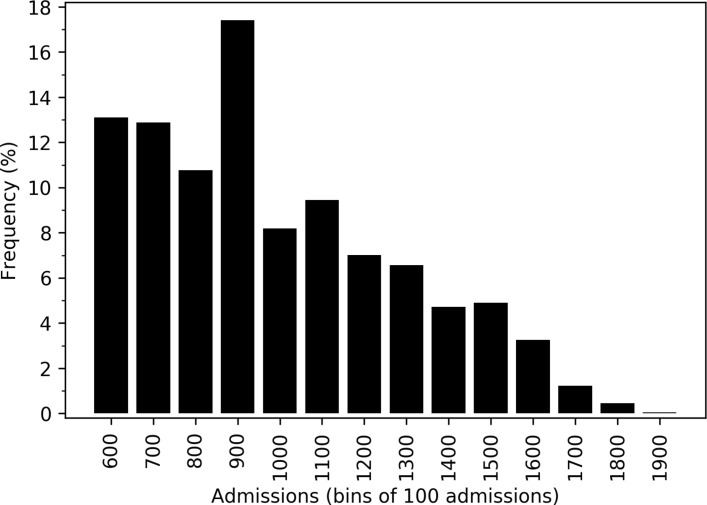

In each configuration it may be important to control the maximum number of admissions to any single unit. Configurations of between 75 and 85 HASUs were identified with all patients attending a unit admitting 600 patients per year, at least 80% of patients within 30 min travel and maximum admissions to any single HASU of no greater than 2000. The algorithm identified 93 configurations in which annual admissions were kept within 600–2000, at least 80% of patients were within 30 min of their closest HASU, and at least 95% and 98% of patients were within 45 and 60 min of their closest unit. The distribution of size of unit among all solutions with yearly admissions per unit within the 600–2000 range was skewed significantly towards lower admissions (figure 5), with only 10% of units having more than 1500 admissions per year.

Figure 5.

Histogram of yearly admissions to hospitals. The histogram shows the distribution of admissions across 93 configurations in which annual admissions were kept within 600–2000 for all units.

Discussion

Our modelling of national configurations of HASUs, designed to replicate the population benefits from centralisation of acute stroke services, has shown the feasibility but also the compromises necessary to maximise these benefits. Currently just over half (56%) of patients with acute stroke are admitted to a stroke unit with at least 600 admissions per year,2 and NHS England proposes to increase this proportion through centralisation in fewer, larger units.14 These HASUs would have staffing levels and competencies as specified in national standards,15 16 and provide intensive (level 2) nursing and medical care for the initial 72 hours after onset (on average) before repatriation of the patient once medically stable to local step-down services for ongoing acute care and rehabilitation. By reducing from the current 127 acute sites to between 75 and 85 HASUs, our centralised HASU model predicts it is possible for all patients with stroke to attend a unit of sufficient size, but with a reduction in the proportion of patients within 30 min travel from the current 90% to 80%–82%, and with 95% and 98% of patients within 45 and 60 min travel, respectively.

Maximising the number of patients attending a HASU with at least 600 stroke admissions per year is not an end in itself. The figure is an approximation for the size of a HASU able to develop and sustain expertise in stroke care,9 and overcome identified barriers to improved care such as thrombolysis.17–19 An association has been observed between door-to-needle time for thrombolysis and institutional size.20 21 Patients admitted to HASUs in areas that have undergone centralisation were found to be more likely to receive other important clinical interventions such as brain scanning and direct admission to a stroke unit sooner.22 However, the corollary of such centralisations is the creation of very large units: the most recent Greater Manchester reconfiguration has created one HASU with over 2000 stroke admissions/year. Our modelling has explored the compromises between institutional size and distance, and the differential effects from centralisation in urban and rural areas. In seeking to balance these often competing priorities, we sought solutions where the largest unit had fewer than 2000 confirmed stroke admissions per year. We observed that in centralised solutions with all hospital admissions between 600 and 2000 admissions per year, fewer than 10% of hospitals would have admissions of more than 1500 per year. Nevertheless, large-scale reconfigurations raise significant issues around the capacity of a small number of very large receiving HASUs, both in infrastructure and workforce, and the potential disbenefits of such large units (if any) are much less well understood. Centralisation to 75–85 hospitals in the manner we have described could therefore be expected to provide a significant benefit to the majority of patients. To yield these benefits, the large majority of patients will travel only moderately further (if at all) to reach a HASU. The disbenefits are to approximately 1.5% of the population who would be more than 60 min away from a reconfigured HASU (compared with an estimated 0.3% with all current acute stroke units), and to the 2% of patients who are currently within 30 min of an existing centre but who, with centralisation, will travel more than 45 min to their nearest HASU. Consideration is therefore needed of how the disbenefits for these patients might be mitigated. Increased travel times might be offset by targeted stroke awareness campaigns (which have been shown to enhance patient response to suspected stroke23) leading to earlier contact of emergency services. Increased travel time may also be offset by reduced door-to-treatment time in the HASU.20 24 More radical solutions for isolated areas include mobile diagnosis and treatment.25 Early diagnostic access and intravenous thrombolysis are particular issues given the paucity of geographical coverage of mechanical thrombectomy in the UK, which promotes a model of ‘drip-and-ship’ (near-patient thrombolysis followed by immediate transfer to a more distant thrombectomy centre); currently only 75% of the English population is within 45 min travel time of one of the current 24 neurosciences centres, where the expertise in this procedure is exclusively concentrated. All of these impacts from reconfiguration are not uniformly distributed, but fall disproportionately on more rural populations, and the existing evidence base from predominantly metropolitan reconfigurations5 7 does not allow a precise estimate of the trade-offs at hand when balancing locality against institutional size—a limitation that will hamper professional and public debate regarding the benefits and consequences of large service reorganisations.

In constructing our model, we have assumed all patients will be taken to their closest HASU. If this is not the case (such as decisions being made instead on organisational boundaries), then some inaccuracy of the model around those boundaries is expected. This will be especially true in areas that have more than one HASU in close proximity; in such cases choice of destination may be influenced by factors (such as institutional reputation) other than shortest travel time. With increasing centralisation, inaccuracies due to the proximity of units will reduce, as fewer patients will be on the boundary where travel time is not the only influence on the destination. We have also sought to avoid infeasibly large units (those larger than any existing HASU with more than 2000 stroke admissions/year), particularly as such an arrangement involves large numbers of stroke-like presentations (‘stroke mimics’) also being conveyed to a HASU—such mimics represent as much as an additional 32% of admissions.26 Centralisation therefore raises significant issues around the capacity of receiving HASUs, both in infrastructure and workforce. Continued capacity at any HASU will depend on the efficient repatriation to locally based post-acute and rehabilitation services (eg, after the first 48–72 hours of care), and we have not modelled these effects or their vulnerability in this paper. There is also uncertainty around the recommended target of 600 admissions per year, not least as random variation would be expected to vary this figure between 550 and 650 (based on a Poisson distribution). With an ageing population, however, we anticipate a steady increase in admissions to hospital with disabling stroke despite better preventative care, particularly in stroke related to atrial fibrillation.27 Although such forecasting is imprecise, a potential increase in stroke incidence and hospital admissions could be driven by a predicted 54% increase in the population of England aged 75 or over the next 15 years.28 Such a rise would militate against enforcing the lower threshold for admissions too strictly (a centre admitting 500 strokes/year at present would very possibly be above that threshold in years to come), and may incline planners to err towards a lower maximum size for any one HASU of, say, 1500 stroke admissions/year, to allow for the projected growth in stroke incidence.

Care should always be taken when considering what appear to be mathematically ‘optimal’ solutions. A model of this size identifies many solutions that have very similar performance, with only marginal differences between them. Our results are therefore best interpreted as showing the broad number of HASUs that are needed on a national or regional scale to deliver the maximum benefit from centralisation, and what impact this is likely to have on a significant minority of patients. Multiple objective optimisation location problems rarely, if ever, have a single explicit solution, and can illuminate but not dictate regional planning, which is still best conducted on a smaller scale, incorporating other local knowledge. Nonetheless, national-level analysis can provide an insight into the range of optimal distributions of stroke centres across England, for which geographical factors are of greater importance than in the predominantly urban reconfigurations that have taken place thus far. For the population of over 8 million people in London, reconfiguration resulted in eight HASUs with a range of annual stroke admissions between 775 and 1288 (or 1023–1700 when FAST-positive stroke mimics are included; FAST, Face, Arm, Speech, Time), and an average ambulance travel time of 17 min2 7; in Greater Manchester, reconfiguration resulted in three HASUs (total stroke admissions between 1073 and 2015/year) serving a population of approximately 2.8 million. The national algorithm has identified many possible configurations in which annual admissions to any HASU are within the range of 600–2000 and with at least 80% of patients within 30 min of their closest HASU. Choosing between approximately similar options will require other considerations to be taken into account, and this is best performed at a regional level, although not at the relatively small ‘footprint’ of many of NHS England’s 44 sustainability and transformation plans, the current geographical unit of planning.

Acute stroke care is evolving, and the development of mechanical thrombectomy for acute large artery stroke is likely to create an imperative for still greater centralisation of services.11 The geographical issues we have identified here will act as an even greater influence on service planning for such specialised treatment, with a similar or more pronounced differential effect between urban and rural environments—removing, for example, the rationale for any metropolitan HASU that is not also capable of delivering mechanical thrombectomy. Further modelling work should be focused on how best to organise care across England when still greater centralisation of some services is required for a significant proportion of patients.

Conclusions

A policy of centralising acute stroke services across England in 75–85 HASUs could realistically achieve 80%–85% of patients attending an acute unit of sufficient size within 30 min travel time (with 95% and 98% being within 45 and 60 min travel, respectively), and with no unit larger than 2000 stroke admissions per year. Although centralisation could offer significant advantages to the large majority of patients, a small minority (2%–4% of the population) would be significantly adversely affected by centralisation, and planning for this minority will inevitably involve compromise between the recommended ideal institutional size and travel times. With centralisation of hyperacute care, thought also needs to be given to optimal organisation of follow-on care at home or in step-down units, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for the South West Peninsula. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors: MA is the lead author and guarantor, and proposed the key methodology to be used in the study. He also contributed to coding of the model. KP wrote much of the code used in the model and contributed to refining the basis of the modelling. She was involved in reviewing and editing the paper. EV developed the initial prototypes of the model employed, testing a number of heuristic approaches. She was involved in reviewing and editing the paper. TM framed the initial problem of balancing access to stroke care with developing a unit of sufficient size to maintain expertise, and recommended the modelling study contained herein. He critiqued the methods used in this study, and was involved in reviewing and editing the paper. KS oversaw all work. He was involved in framing the problem to be modelled. He critiqued the methods used in this study, and was involved in reviewing and editing the paper. MJ is the clinical stroke consultant for the work and paper. He was involved in framing the problem to be modelled. He advised on the clinical objectives of the study, was involved in authoring, reviewing and editing the paper.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for the South West Peninsula. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. TM was funded by NIHR CLAHRC Wessex.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Full data and code used for this study are available at https://github.com/MichaelAllen1966/stroke_unit_location. Included in the data and code are counts of acute stroke admissions in England by LSOA; estimated travel times from all LSOAs to al acute stroke units; hospital information (name, location); and full source code used to produce results reported here (which runs using open source software).

Author note: The lead author (MA) confirms that the manuscript is a honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported, and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

References

- 1. Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2014;383:245–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61953-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Royal College of Physicians. Sentinel Stroke Audit Programme (SSNAP). 2016. https//www.strokeaudit.org/Documents/Results/National/Apr2015Mar2016/Apr2015Mar2016-AnnualResultsPortfolio.aspx

- 3. Newton JN, Briggs AD, Murray CJ, et al. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:2257–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00195-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NHS England. Putting patients first: the NHS business plan 2013/4 - 2015/6. 2013. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/ppf-1415-1617-wa.pdfhttps://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/ppf-1314-1516.pdf

- 5. Morris S, Hunter RM, Ramsay AI, et al. Impact of centralising acute stroke services in English metropolitan areas on mortality and length of hospital stay: difference-in-differences analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g4757 10.1136/bmj.g4757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hunter RM, Davie C, Rudd A, et al. Impact on clinical and cost outcomes of a centralized approach to acute stroke care in London: a comparative effectiveness before and after model. PLoS One 2013;8:e70420–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fulop N, Boaden R, Hunter R, et al. Innovations in major system reconfiguration in England: a study of the effectiveness, acceptability and processes of implementation of two models of stroke care. Implement Sci 2013;8:5 10.1186/1748-5908-8-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Price C, James M. Meeting the future challenge of stroke meeting the future challenge of stroke. Br Assoc Stroke Physicians 2011. www.basp.ac.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 9. NHS England. Stroke services: configuration decision support guide. 2015. www.eoescn.nhs.uk/index.php/download_file/force/2069/168/

- 10. Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 2014;384:1929–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016;387:1723–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monks T, Pitt M, Stein K, et al. Hyperacute stroke care and NHS England’s business plan. BMJ 2014;348:g3049 10.1136/bmj.g3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deb K, Pratap A, Agarwal S, et al. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans Evol Comput 2002;6:182–97. 10.1109/4235.996017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. NHS England. Our Business Plan 2016/17. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/bus-plan-16.pdf

- 15. Royal College of Physicians of London. Intercollegiate stroke working party national clinical guideline for stroke. 5th Edition London: Royal College of Physicians of London, 2016. www.strokeaudit.org.uk/guideline (accessed 2 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16. NHS England. Seven Day Services Clinical Standards. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/clinical-standards-feb17.pdf

- 17. Eissa A, Krass I, Bajorek BV. Barriers to the utilization of thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. J Clin Pharm Ther 2012;37:399–409. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01329.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carter-Jones CR. Stroke thrombolysis: Barriers to implementation. Int Emerg Nurs 2011;19:53–7. 10.1016/j.ienj.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Monks T, Pitt M, Stein K, et al. Maximizing the population benefit from thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: a modeling study of in-hospital delays. Stroke 2012;43:2706–11. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.663187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bray BD, Campbell J, Cloud GC, et al. Bigger, faster? Associations between hospital thrombolysis volume and speed of thrombolysis administration in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2013;44:3129–35. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Strbian D, Ahmed N, Wahlgren N, et al. Trends in Door-to-Thrombolysis Time in the Safe Implementation of Stroke Thrombolysis Registry. Stroke 2015;46:1275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramsay AI, Morris S, Hoffman A, et al. Effects of centralizing acute stroke services on stroke care provision in two large metropolitan areas in England. Stroke 2015;46:2244–51. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mellon L, Doyle F, Rohde D, et al. Stroke warning campaigns: delivering better patient outcomes? A systematic review. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2015;6:61 10.2147/PROM.S54087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meretoja A, Strbian D, Mustanoja S, et al. Reducing in-hospital delay to 20 minutes in stroke thrombolysis. Neurology 2012;79:306–13. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825d6011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kunz A, Ebinger M, Geisler F, et al. Functional outcomes of pre-hospital thrombolysis in a mobile stroke treatment unit compared with conventional care: an observational registry study. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:1035–43. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30129-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dawson A, Cloud GC, Pereira AC, et al. Stroke mimic diagnoses presenting to a hyperacute stroke unit. Clin Med 2016;16:423–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-5-423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yiin GS, Howard DP, Paul NL, et al. Recent time trends in incidence, outcome and premorbid treatment of atrial fibrillation-related stroke and other embolic vascular events: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:12–18. 10.1136/jnnp-2015-311947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Office of National Statistics. Office of National Statistics (2014). 2014-based subnational population projections. 2014. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/datasets/regionsinenglandtable1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018143supp001.pdf (122.8KB, pdf)