Abstract

Background. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use is common among cancer patients, but the majority of CAM studies do not specify the time periods in relation to cancer diagnoses. We sought to define CAM use by cancer patients and investigate factors that might influence changes in CAM use in relation to cancer diagnoses. Methods. We conducted a cross-sectional survey of adults diagnosed with breast, prostate, lung, or colorectal cancer between 2010 and 2012 at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Questionnaires were sent to 1794 patients. Phone calls were made to nonrespondents. Log binomial/Poisson regressions were used to investigate the association between cancer-related changes in CAM use and conversations about CAM use with oncology providers. Results. We received 603 (33.6 %) completed questionnaires. The mean age (SD) was 64 (11) years; 62% were female; 79% were white; and 98% were non-Hispanic. Respondents reported the following cancer types: breast (47%), prostate (27%), colorectal (14%), lung (11%). Eighty-nine percent reported lifetime CAM use. Eighty-five percent reported CAM use during or after initial cancer treatment, with category-specific use as follows: mind-body medicine 39%, dietary supplements 73%, body-based therapies 30%, and energy medicine 49%. During treatment CAM use decreased for all categories except energy medicine. After treatment CAM use returned to pretreatment levels for most CAMs except chiropractic. Initiation of CAM use after cancer diagnosis was positively associated with a patient having a conversation about CAM use with their oncology provider, mainly driven by patient-initiated conversations. Conclusions. Consistent with previous studies, CAM use was common among our study population. Conversations about CAM use with oncology providers appeared to influence cessation of mind-body medicine use after cancer diagnosis.

Keywords: complementary and alternative medicine, patient-provider communication, treatment phase, patient behavior, cancer survivorship

Introduction

A systematic review of surveys on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among cancer patients in North America, Europe, and Australia/New Zealand found that the United States has the highest CAM use among cancer patients, and its CAM use has been increasing over the past 3 decades.1 The CAM prevalence among cancer patients was estimated at around 60% to 80%, but it depends on factors such as cancer type, sampling methods, time recalls, and decade of study.1-6

Cancer care providers’ knowledge of their patients’ CAM use is becoming important because of potential interactions with routine cancer treatments.7,8 Cancer survivors are more likely to use CAM because of recommendations from their providers and are more likely to disclose their CAM use to their provider than noncancer controls,9 although the nondisclosure rate still remains high, estimated at around 80% (77% to 84%).9,10

The majority of studies on CAM use among cancer patients do not specify the time periods in relation to cancer diagnoses, or the time periods of CAM use are highly varied among included individuals.1 Having information on CAM use over different time periods in relation to cancer diagnosis will allow investigation of change in patient behavior, thus facilitating patient-provider discussion of the risks of benefit and harm of CAM use over these time periods and referring patients to providers who are trained to discuss CAM. When this information is combined with information on patient-provider communication, it can provide insight into the role of patient-provider communication in cancer patients’ CAM use.

Using a questionnaire-based survey, we aimed to yield point estimates of CAM use among adult cancer patients treated in the past 2 years with the 4 most common cancers: breast, lung, prostate, or colorectal. Specifically, we assessed CAM in the following 3 time periods: before, during, and after initial cancer treatment in order to identify cancer-related changes in CAM use. We also investigated the communication patterns between patients and oncology providers and how that was associated with cancer-related CAM change.

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of adult cancer patients seeking care at the North Carolina Cancer Hospital (NCCH) between 2010 and 2012. Eligible participants were English-speaking, between 21 and 99 years of age, and diagnosed with breast, prostate, lung, or colorectal cancer between 2010 and 2012. Participants were identified from the University of North Carolina (UNC) Tumor Registry, which is a comprehensive database of patients diagnosed with cancer at the NCCH, the clinical home of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC). Potential participants were mailed an introductory letter, questionnaire, and a return-postage envelope. Follow-up telephone call and a second questionnaire were sent to nonrespondents. We made up to 3 attempts to contact patients by telephone. The Institutional Review Board at UNC approved the research protocol, and all study participants gave informed consent.

Data Collection

We adapted a questionnaire used by Richardson et al11 to assess CAM use at a comprehensive cancer center. We asked about CAM use in 4 primary categories: mind-body medicine, dietary supplements, body-based therapies, and energy medicine. We also queried use of whole medical systems such as traditional Chinese medicine and ayurveda. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever used specific CAM therapies in each of these categories, and if so, when that use occurred in relation to their initial cancer treatment (ie, before, during, or after). Information on sources of advice on CAM use and discussion of CAM use with oncology providers was also gathered. The questionnaire was pilot-tested on volunteers for readability and face validity. The tumor registry provided demographic and clinical data such as diagnosis date, tumor type and stage, and treatment history.

Statistical Analysis

We provide descriptive data for age, sex, as well as cancer type and stage, in addition to prevalence of CAM use (frequency, percentage). Patients with stage 0 and stage 1 cancers were combined into an “early-stage cancer” group because of their prognostic and treatment similarities when compared with later-stage cancers.

We used log-binomial and Poisson regression to investigate how communication of CAM was associated with changes in CAM use after cancer diagnosis. For all regressions, we started with the full model that included variables such as age, education level, cancer type and cancer stage, and ran backward elimination to come up with the most succinct model (likelihood ratio test cutoff P = .05). All breast cancer cases were female, all prostate cancer cases were male, so following previous studies, we did not adjust for sex in these regressions.4 The analyses were performed using Stata IC Version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

We sent out 1794 questionnaires and received 603 (33.6%) completed questionnaires. The mean age of respondents was 63.5 (±11.0) years. Sixty-two percent of respondents were female, 79% were white, and 98% were non-Hispanic. Compared with nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be white (79.3% vs 68.4%), female (61.7% vs 55.3%), have breast cancer (46.9% vs 39.4%), and have early-stage cancer (46.4% vs 39.5%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristic of Respondents and Nonrespondents.

| Characteristics | Respondents (N = 603) | Nonrespondents (N = 1189) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 63.5 (11.0) | 61.1 (12.0) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 372 (61.7) | 657 (55.3) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 476 (78.9) | 809 (68.0) |

| Ethnicity, non-Hispanic, n (%) | 591 (98.0) | 1141 (96.0) |

| Cancer type, n (%) | ||

| Breast | 283 (46.9) | 468 (39.4) |

| Prostate | 164 (27.2) | 331 (27.8) |

| Colorectal | 87 (14.4) | 221 (18.6) |

| Lung | 69 (11.4) | 169 (14.2) |

| Cancer stage,a n (%) | ||

| 0-1 | 278 (46.4) | 463 (39.5) |

| 2 | 214 (35.7) | 450 (38.4) |

| 3 | 68 (11.4) | 158 (13.5) |

| 4 | 39 (6.5) | 102 (8.7) |

Of all surveyed participants (respondents and nonrespondents), 160 were cancer stage “0” and 581 patients were stage “1.” Among 160 stage “0” participants, 144 (90%) had breast cancer; among 581 stage “1” patients, 259 (45%) had breast cancer. Nine patients’ cancer stage was unknown.

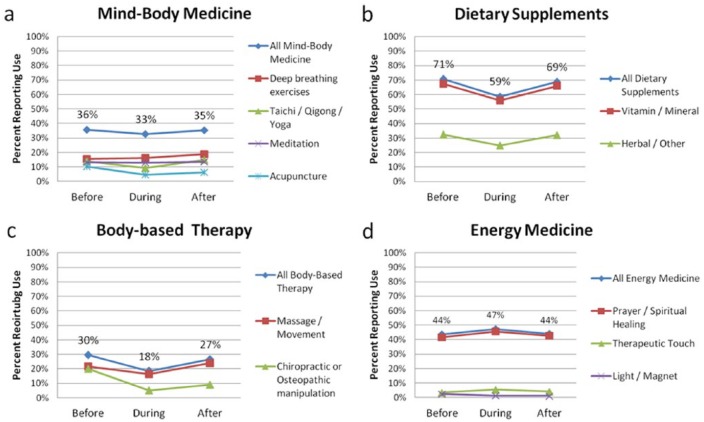

Eighty-nine percent of respondents reported ever using a CAM therapy during their lifetime. CAM use appeared to decrease during active cancer treatment compared with use prior to treatment for all CAM categories except energy medicine, which was largely driven by prayer and spiritual healing practices (Figure 1). CAM use was common both during and after cancer treatment for all CAM therapy categories. The most common therapies used included: vitamin and mineral supplements (56% and 66%, during and after treatment, respectively); prayer and spiritual healing (46% and 43%); herbal supplements (25% and 32%), massage and movement therapy (16% and 24%); and deep breathing exercises (16% and 19%). Use of CAM therapies after treatment returned to pretreatment levels for most CAMs with the exception of chiropractic, which dropped during active treatment and remained low after treatment (20% vs 5% vs 9%).

Figure 1.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapy use before, during, and after active cancer treatment (N = 603). Each graph depicts total proportion of participants that used at least one therapy for that category of CAM therapy (diamond lines). Proportions for individual CAM therapies are represented in the lower lines. For example, during cancer treatment, about 59% of our population reported taking a dietary supplement (Figure 1b). Almost all participants who reported taking a supplement took a vitamin or mineral supplement (square line), and about 44% (0.26/0.59) reported taking an herbal or other type of supplement (triangle line).

In the periods after cancer diagnosis (ie, during and after cancer treatment), 85% of respondents reported using at least one CAM therapy. CAM use was most common among breast cancer patients (93%), followed by colorectal cancer (83%), prostate cancer (77%), and lung cancer (77%; Table 2). For patients of each of the 4 cancer types, dietary supplements were the most commonly used CAM modality (52% to 82%), followed by energy medicine (39% to 55%), mind-body medicine (16% to 52%), and body-based therapy (14% to 42%).

Table 2.

CAM Use During or After Initial Cancer Treatment for Each Cancer Type.

| Cancer Type | CAM Use by CAM Therapy Category, n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any CAM | MBM | DS | BBT | EM | |

| All (N = 603) | 514 (85.2) | 236 (39.1) | 437 (72.5) | 181 (30.0) | 294 (48.8) |

| Breast (n = 283) | 262 (92.6) | 148 (52.3) | 231 (81.6) | 120 (42.4) | 156 (55.1) |

| Prostate (n = 164) | 127 (77.4) | 26 (15.9) | 103 (62.8) | 23 (14.0) | 66 (40.2) |

| Colorectal (n = 87) | 72 (82.8) | 38 (43.7) | 63 (72.4) | 22 (25.3) | 45 (51.7) |

| Lung (n = 69) | 53 (76.8) | 24 (34.8) | 40 (58.0) | 16 (23.2) | 27 (39.1) |

Abbreviations: CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; MBM, mind-body medicine; DS, dietary supplement; BBT, body-based therapy; EM, energy medicine.

Most patients who used CAM therapy during or after cancer treatment were likely to use more than 1 CAM therapy simultaneously (58%; Table 3). Twenty-eight percent of respondents reported using only 1 CAM therapy, which was most often a dietary supplement (71%).

Table 3.

Number of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies Used During or After Cancer Treatment.

| Cancer Type | Number of Therapies Used, n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | >1 | |

| Breast (n = 283) | 21 (7.4) | 61 (21.6) | 201 (71.0) |

| Prostate (n = 164) | 37 (22.6) | 65 (39.6) | 62 (37.8) |

| Colorectal (n = 87) | 15 (17.2) | 22 (25.3) | 50 (57.5) |

| Lung (n = 69) | 16 (23.2) | 19 (27.5) | 34 (49.3) |

| All respondents (N = 603) | 89 (14.8) | 167 (27.7) | 347 (57.6) |

Twenty-three percent (136/603) of all respondents reported having a conversation about CAM with their oncology provider. Initiation of CAM use any time after cancer diagnosis was positively associated with a patient having a conversation about CAM use with their oncology provider (Table 4). Further analysis revealed the increased likelihood of new CAM use was more driven by patient-provider interactions in which patients initiated conversation about CAM, rather than CAM conversations initiated by cancer care provider (data not shown). Cessation of CAM therapy use during or after initial cancer treatment, on the other hand, was negatively associated with patient-provider conversation for MBM (prevalence ratio = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.22-0.93; Table 5). In other words, patients who had conversations with providers were less likely to cease MBM therapies during or after initial cancer treatment. We found no association between cancer type and either initiation or cessation of CAM use. We found no association between more advanced cancer stage and number of CAM therapies. We found no association between the type of treatment and CAM use or change (initiation and cessation) in CAM use since diagnosis.

Table 4.

Association of New CAM Use After Cancer Diagnosis and Conversation About CAM With Oncology Provider.

| CAM Therapy | No CAM Use Prior to Diagnosis, n | New CAM Use After Diagnosis,a n (%) | Prevalence Ratio (95% CI)b | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBM | 366 | 52 (14.2) | 1.79 (1.07-2.99) | .03 |

| DS | 162 | 63 (38.9) | 1.83 (1.05-3.19) | .03 |

| BBT | 401 | 46 (11.5) | 3.31 (1.85-5.94) | .00 |

| EM | 321 | 38 (11.8) | 2.83 (1.48-5.44) | .00 |

Abbreviations: CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; MBM, mind-body medicine; DS, dietary supplement; BBT, body-based therapy; EM, energy medicine.

New CAM use is defined as CAM therapy use changed from “No” before cancer diagnosis to “Yes” after cancer diagnosis.

Model adjusted for age, education, cancer type and cancer stage for MBM; adjusted for cancer type, cancer stage for DS; adjusted for cancer type for BBT, adjusted for age for EM.

Table 5.

Association of Cessation of CAM Use After Cancer Diagnosis With Conversation About CAM With Oncology Provider.

| CAM Therapy | CAM Use Prior to Diagnosis, n | Cessation of CAM Use After Diagnosis,a n (%) | Prevalence Ratio with 95% CIb | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBM | 210 | 57 (27.1) | 0.46 (0.22-0.93) | .03 |

| DS | 414 | 111 (26.8) | 0.85 (0.57-1.28) | .44 |

| BBT | 175 | 97 (55.4) | 0.87 (0.63-1.19) | .37 |

| EM | 255 | 19 (7.5) | 1.57 (0.65-3.84) | .32 |

Abbreviations: CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; MBM, mind-body medicine; DS, dietary supplement; BBT, body-based therapy; EM, energy medicine.

Cessation of CAM usage is defined as CAM therapy use changed from “Yes” before active cancer treatment to “No” during/after cancer treatment.

Model adjusted for cancer type.

Discussion

We set out to describe CAM use among cancer patients, as well as the communication pattern between patients and provider and its association with patients’ CAM use. We collected data on CAM use before, during, and after initial cancer treatment using a cancer patient sample at University of North Carolina Cancer Hospital, which allowed us to investigate changes in CAM use over time. We had data for discrete time periods related to time of diagnosis, which helped us understand CAM use before, during, and after treatment.

We found high lifetime CAM use (89%) in our population. The response rate is slightly higher among breast cancer patients, a subgroup that is known to use CAM therapies more than patients of other cancer types. Nevertheless, this prevalence is similar compared to previous studies in cancer populations.11 Richardson et al11 found 83% of the cancer patients used at least 1 CAM therapy. Yates et al12 found CAM use as high as 91% among cancer patients during chemotherapy and radiation. However, differences in the definition of CAM modalities for each study may confound comparison of these prevalence estimates. For example, Yates et al12 found that “prayer,” “relaxation,” and “exercise” were the most commonly used CAM therapies. But, our question about prayer defined the activity as “prayer for healing” rather than a general question about any prayer. Not surprisingly, our estimates for prayer were lower than those reported by Yates et al12 (45% vs 77%, respectively). Similarly, we asked about specific exercises such as T’ai chi, Qiqong, and yoga, rather than a general question about exercise. Accordingly, we found that during initial cancer treatment, dietary supplements, not prayer or exercise, were the most common CAM therapy used, followed by energy medicine (in which prayer is the main driver), and then mind-body medicine, and body-based therapies. Dietary supplements have been reported to be the most common CAM therapy in a few other studies, including one study that used the 2007 National Health Interview Survey.4,13

We found that CAM use generally decreased during active cancer treatment compared with use prior to diagnosis and returned to pretreatment levels after completion of cancer treatment. Notable exceptions to this trend were sustained levels of prayer, spiritual healing, deep breathing exercise, and light/magnet therapy during cancer treatment. The reason for the decrease of CAM use during cancer treatment may be 2-fold. First, doctors and health providers might have spoken to patients and advised against CAM use, although in our study we did not collect data on whether the doctor recommended for or against CAM use. Second, when patients are diagnosed with cancer and start the subsequent counseling and treatment, the process is complex and cognitively taxing for the patients. Such large cognitive load and high volume of complex decision making have been linked to decision fatigue and thus decision simplification strategies.14-16

Interestingly, posttreatment levels of chiropractic remained low, suggesting patients may have been uncomfortable returning to that therapy based on their cancer diagnosis.

For patients’ CAM use by cancer types, we found the highest CAM use among breast cancer patients, followed by colorectal cancer patients, and then prostate and lung cancer patients. A similar pattern across cancer types is also seen in a few other studies. For example, Patterson et al,4 using a telephone survey of cancer patients identified from the population-based Cancer Surveillance System of Western Washington, found that CAM use was highest among breast cancer patients (87%), followed by colorectal (64%) and prostate (59%) cancer patients. Lafferty et al,17 using a registry-matched insurance claims database, also noted a similar pattern: Compared with colorectal cancer patients, breast cancer patients had higher CAM use during initial treatment and continued use after treatment (odds ratio [OR] = 1.85, 95% CI =1.19-2.87 and OR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.29-3.22, respectively), prostate cancer patients has slightly higher or similar CAM use (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 0.71-1.81 and OR = 1.28, 95% CI = 0.79-2.09, respectively) during and after treatment, followed by lung cancer patients (OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 0.72-2.38 and OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.53-2.07, respectively).

We found that initiation of CAM therapy across all four CAM categories during and after cancer treatment was positively associated with having a conversation about CAM with an oncology provider. Although we do not have information on the content of those conversations, our data show that patients who initiated a conversation with their medical provider about CAM use were also more likely to initiate new CAM use after diagnosis. Although it is possible that some oncology providers may have been suggesting use of some CAM therapies, it is more likely that patients who were motivated to discuss CAM therapies with their providers were also strongly motivated to use them prior to their discussions.

Our findings have implications for communications between oncology providers and cancer patients. First, patients who initiate a conversation about CAM are more likely to initiate CAM use. In their communications about CAM therapies with providers, patients often recognize that medical providers are typically not CAM experts and they are especially concerned about negative responses from their providers.18 While most cancer patients use CAM in order to boost the immune system, relieve pain, and control side effects as a result of disease or treatment,19 they are typically looking for the best of both worlds: CAM plus conventional cancer treatment together.20 However, nondisclosure of CAM use to cancer care providers remains common.18,21 Given the high prevalence of CAM use among cancer patients, emerging evidence that certain CAM therapies can improve patient quality of life and reduce treatment and disease-related symptoms, and the potential interaction between some CAM therapies and conventional cancer treatment, we encourage oncology providers to discuss CAM use with their patients in an open and nonjudgmental fashion in order to facilitate patient-centered communication as well as participatory patient decision making.22

Second, if oncology providers wish to influence their patient’s decisions about CAM use, they may need to use additional strategies and resources to help them. For example, recommendations about specific dietary supplement-drug interactions may be more persuasive for patients compared to general recommendations to avoid supplements altogether during treatment. Where oncologists do not have such expertise, cancer centers could employ pharmacy and CAM specialists who are trained to discuss supplement-drug interactions.

Limitations

Our response rate was low, which may bias our prevalence estimates for overall CAM use. However, the rate of CAM use among respondents was very high, suggesting that our sample may have included most of the CAM users among our patient population. As such, the information we have on communication among CAM users remains relevant, especially for the early stage cancers were the response rates were highest. Additionally, we can estimate CAM use prevalence using sensitivity analysis. For example, assuming that only 10% of nonrespondents used CAM therapies during or after cancer diagnosis on the lower boundary and 30% were CAM users on the upper boundary (514/1794 = 29%), then we can estimate the prevalence of CAM use during or after cancer treatment lies between 37% and 49%. Second, this is a retrospective study, and we relied on participants for the accuracy and completeness of their responses. Third, we did not collect information on other possible factors which may affect patients’ CAM uptake and change in CAM use. Last, we recognize that advanced-stage cancer patients were only 6.5% of our study population and as a result our study results may not fully represent patients with advanced cancers.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dionne Apple, Neha Verma, and Gavriella Hecht for their help in administering the survey and the UNC Odum Institute for their contribution to the creation and testing of the questionnaire.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this research was provided by North Carolina University Cancer Research Fund and the UNC Department of Family Medicine Small Grants Fund.

References

- 1. Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G, Less D, Ritter E, Zwahlen M. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:187-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vapiwala N, Mick R, Hampshire MK, Metz JM, DeNittis AS. Patient initiation of complementary and alternative medical therapies (CAM) following cancer diagnosis. Cancer J. 2006;12:467-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perlman A, Lontok O, Huhmann M, Parrott JS, Simmons LA, Patrick-Miller L. Prevalence and correlates of postdiagnosis initiation of complementary and alternative medicine among patients at a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:34-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM, et al. Types of alternative medicine used by patients with breast, colon, or prostate cancer: predictors, motives, and costs. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:477-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hann DM, Baker F, Roberts CS, et al. Use of complementary therapies among breast and prostate cancer patients during treatment: a multisite study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4:294-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sparber A, Wootton JC. Surveys of complementary and alternative medicine: part II. Use of alternative and complementary cancer therapies. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:281-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Golden EB, Lam PY, Kardosh A, et al. Green tea polyphenols block the anticancer effects of bortezomib and other boronic acid-based proteasome inhibitors. Blood. 2009;113:5927-5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sparreboom A, Cox MC, Acharya MR, Figg WD. Herbal remedies in the United States: potential adverse interactions with anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2489-2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mao JJ, Palmer CS, Healy KE, Desai K, Amsterdam J. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Metz JM, Jones H, Devine P, Hahn S, Glatstein E. Cancer patients use unconventional medical therapies far more frequently than standard history and physical examination suggest. Cancer J. 2001;7:149-154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, Greisinger A, Singletary SE. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2505-2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yates JS, Mustian KM, Morrow GR, et al. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients during treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:806-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson JG, Taylor AG. Use of complementary therapies for cancer symptom management: results of the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:235-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Danziger S, Levav J, Avnaim-Pesso L. Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6889-6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, Green RA, Zhang J, Patel VL. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76:801-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tyler JM, Burns KC. After depletion: the replenishment of the self’s regulatory resources. Self Identity. 2008;7:305-321. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lafferty WE, Tyree PT, Devlin SM, Andersen MR, Diehr PK. Complementary and alternative medicine provider use and expenditures by cancer treatment phase. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:326-334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:90-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mansky PJ, Wallerstedt DB. Complementary medicine in palliative care and cancer symptom management. Cancer J. 2006;12:425-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;(343):1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davis EL, Oh B, Butow PN, Mullan BA, Clarke S. Cancer patient disclosure and patient-doctor communication of complementary and alternative medicine use: a systematic review. Oncologist. 2012;17:1475-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sohl SJ, Borowski LA, Kent EE, et al. Cancer survivors’ disclosure of complementary health approaches to physicians: the role of patient-centered communication. Cancer. 2015;121:900-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]