Abstract

Naturopathic oncology is a relatively new and emerging field capable of providing professional integrative or alternative services to cancer patients. Foundational research is critical to identify topics in the clinical and research development of naturopathic oncology for future growth of the field. Study design. This study implements a modified Delphi protocol to develop expert consensus regarding ethics, philosophy, and research development in naturopathic oncology. Methods. The modified protocol implements a nomination process to select a panel of 8 physicians and to assist in question formulation. The protocol includes an in-person discussion of 6 questions with multiple iterations to maintain the concept of the Delphi methodology as well as a postdiscussion consensus survey. Results. The protocol identified, ranked, and established consensus for numerous themes per question. Underlying key topics include integration with conventional medicine, evidence-based medicine, patient education, patient safety, and additional training requirements for naturopathic oncologists. Conclusions. The systematic nomination and questioning of a panel of experts provides a foundational and educational resource to assist in clarification of clinical ethics, philosophy, and research development in the emerging field of naturopathic oncology.

Keywords: naturopathic, oncology, Delphi, integrative, medicine, complementary and alternative medicine, ethics, philosophy, research

Introduction

The Delphi method was developed by the RAND Corporation in the 1950s in collaboration with the United States military as a technique to predict the impact of technology on warfare and identify long-term threat assessment.1,2 Over the past 60 years, its implementation has expanded into medical research as a methodology capable of producing both qualitative and quantitative data. In its basic and original form, the Delphi method is a systematic approach to consensus development by repeated question and answer analysis.1,2 A small panel of experts is used in the Delphi process, and they apply their knowledge to develop a group consensus and assist in decision making, policy formation, and/or clarification of a debated topic of interest.2 The ability of the Delphi method to develop consensus regarding a debated or unknown topic makes it an ideal research methodology to assist in the development of new and emerging fields of medicine.

Naturopathic oncology is a subdiscipline of naturopathic medicine applying the principles of naturopathy to the field of oncology. This evolving field of medicine has continued to expand over the past few decades and now has a presence in mainstream cancer institutes and private practices across the United States.3 Naturopathic medicine is often considered a form of complementary and alternative medicine. The prevalence of cancer patients who seek alternative medicine during treatment varies among studies; however, even as early as 2000, Richardson et al4 reported that 83.3% of surveyed cancer patients used at least 1 form of alternative medicine. This high percentage exemplifies the need for professionally trained physicians to offer integrative and complementary support to cancer patients. Licensed naturopathic physicians attend 4-year postgraduate, accredited medical schools and have the opportunity to sit for additional credentialing specific to oncology. The Oncology Association of Naturopathic Physicians (OncANP) is the specialty organization for naturopathic oncology recognized by the profession’s national organization, the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians.5

Naturopathic oncology is currently a relatively small and youthful field. OncANP was founded in 2004, and there are currently 101 licensed naturopathic physicians with the additional credentialing of Fellow of the American Board of Naturopathic Oncologists (FABNO) and roughly 5000 licensed naturopathic physicians in North America.5,6 These licensed physicians can offer cancer-specific support to patients within their respective state and provincial statutes; however, the OncANP, under the direction of its partner organization, the American Board of Naturopathic Oncology (ABNO), administers and establishes the eligibility criteria for FABNO credentialing.

The Delphi method has never previously been implemented in naturopathic oncology, but used in naturopathic medicine for various purposes. Leaver et al7 employed the Delphi method to identify consensus and variance to the clinical approach of cervical atypia among a panel of naturopathic physicians. Shinto et al8 also implemented the Delphi method to assist in developing best-practice protocols for the naturopathic approach to multiple sclerosis. Additional fields of medicine have applied the Delphi method to identify appropriate safety protocols for dental implant procedures,9 determine the continuing education needs and issues of general practitioners who see cancer patients,10 and develop ethical strategies to assist oncologists in obtaining informed consent to enroll their patients in clinical trials.11 More general uses of the Delphi method in health care are highlighted by Falzarano and Pinto Zipp12 and include obtaining professional and expert judgment regarding a specific subject,13-18 gathering opinions and setting priorities related to clinical practice or research,19-21 validating research tools or survey items,22-26 and also confirming theoretical concepts.19,27-30

This study implements the Delphi method to establish consensus among a panel of experts regarding ethical, philosophical, and research development concepts relating to naturopathic oncology. The intention of this study is to provide educational and foundational information to assist in the development of the field. The original Delphi methodology, as developed by the RAND Corporation, was modified to accommodate time and location constraints and also modified to allow numerous naturopathic oncologists to participate in a research study that attempts to develop their field of practice. Modification of the original Delphi methodology is common practice. Boulkedid et al31 conducted a systematic review of Delphi studies used to formulate health care quality indicators and found that 49/78 (68%) of the panels used a modified Delphi technique.

Methods

This project was a collaborative effort between the Helfgott Research Institute and the OncANP. Collaboration was essential to allow the research facility access to the majority of naturopathic oncologists via the OncANP online e-mail forum. The ideal location to conduct the panel was determined to be the OncANP annual conference.

Panel Nomination and Selection

A summary of the Delphi study and protocol was distributed on the OncANP online forum. The members of the OncANP were encouraged to select and nominate 8 physicians to represent the field of naturopathic oncology and sit on the Delphi panel to discuss and debate questions regarding ethics, philosophy, and research development. The members were encouraged to self-nominate if they desired to be considered for selection to the panel of experts. The OncANP members were asked to share the e-mail, study summary, and nomination request with any colleague in the field of naturopathic oncology. This request was made in an attempt to allow naturopathic oncologists who are not members of OncANP to nominate themselves or their desired representatives. A total of 389 members subscribed to the forum at the time the study summary was posted, and 39 physicians received nominations from their colleagues in the field of naturopathic oncology.

In addition to nominating other physicians in the field, the OncANP members were encouraged to self-nominate, indicating that they were interested in participating in the study, able to attend the panel at the designated time and location, and met all the criteria and qualifications required to participate. The required qualifications to be considered for panel selection are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Requirements for Participation on the Modified Delphi Panel.

| 1. Hold a degree of Doctorate of Naturopathic Medicine from a 4-year accredited medical school |

| 2. Attend the third annual OncANP conference during the date and time of the modified Delphi panel |

| 3. Have a minimum of 7 years of experience with a majority (>50%) of patients seeking cancer treatment or support |

| 4. Sign a consent form providing permission to use the participant’s name, biography, and any recorded dialogue in the final publication |

Abbreviations: OncANP, Oncology Association of Naturopathic Physicians.

All nominations and self-nominations were collected and summated. Any physician who received 2 or more nominations was contacted by the Delphi director via e-mail to inform them of their nomination and inquire about their interest in participation. Any physicians who self-nominated or expressed interest in participation on the panel were required to submit additional information to assist in panel member selection. The additional information required for consideration for selection to the panel is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Additional Information Required for Consideration of Panel Selection.

| 1. Personal statement of philosophy to naturopathic oncology |

| 2. Years of clinical experience |

| 3. Type of clinical work (hospital/private practice, licensed/unlicensed state or province) |

| 4. Research and publications |

| 5. Additionally related information |

This additional required information and total number of nominations was organized into a rubric format used to compare the physicians. The rubric assisted in selecting panel members with a combination of the following: (1) the most years of clinical and/or research experience, (2) varied philosophical approaches to naturopathic oncology, (3) relevant additional oncology experience pertinent to the topic of ethics, philosophy, and/or research development, and (4) a higher number of colleague nominations. A total of 15 physicians provided self-nominations and the required additional information for consideration for panel selection. Two physicians were removed from consideration because they had less than 7 years of clinical experience. The research team unanimously selected the physicians who satisfied the rubric categories for panel qualification to the greatest degree.

Panel Participants

A total of 8 physicians in the field of naturopathic oncology were selected to participate in the panel discussion. The names of the panel members are listed in Table 3, and the demographics and characteristics of the panel physicians are described in Table 4. All participants signed an informed consent for participation in the study. The informed consent provided a detailed explanation of the purpose of the study, potential use of the recorded discussion, and intent to publish. Participants were permitted to revoke their permission for use of their recorded discussion at any time.

Table 3.

Naturopathic Oncologists on the Naturopathic Oncology Modified Delphi Panel.

| Tim Birdsall, ND, FABNO |

| Daniel Rubin, ND, FABNO |

| Gurdev Parmar, ND, FABNO |

| Neil McKinney, NDa |

| Davis Lamson, ND, MSa |

| Lise Alschuler, ND, FABNO |

| Dugald Seely ND, MS, FABNO |

| Shauna Birdsall, ND, FABNO |

These panelists do not carry the credential of FABNO but were selected for the panel because of their extensive experience as professors and clinicians of naturopathic oncology.

Table 4.

Delphi Panel Participant Characteristics (n = 8).

| Range | Mean | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years practicing naturopathic medicine | 11-32 | 20.5 | — |

| Years practicing naturopathic oncologya | 8-25 | 14.4 | — |

| Age (years) | 40-79 | 52.5 | |

| Naturopathic medical school attended | |||

| Bastyr University | 3 | ||

| Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine | 2 | ||

| National College of Natural Medicine | 2 | ||

| Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine | 1 | ||

| Credentials | |||

| ND | 1 | ||

| ND, FABNO | 5 | ||

| ND, MS | 1 | ||

| ND, MS, FABNO | 1 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 2 | ||

| Male | 6 | ||

| Current type of practice | |||

| Hospital | 2 | ||

| Private practice or integrative medical clinic | 6 | ||

| Location of practice (country) | |||

| Canada | 3 | ||

| United States | 5 | ||

| Location of practice (state/province) | |||

| Arizona | 4 | ||

| British Columbia | 2 | ||

| Ontario | 1 | ||

| Washington (State) | 1 | ||

| Location of practice (licensure for naturopathic medicine) | |||

| Licensed state/province | 8 | ||

| Unlicensed state/province | 0 | ||

Abbreviations: ND, Naturopathic Doctor; FABNO, Fellow of the American Board of Naturopathic Oncologists.

Values indicate number of years treating a majority (>50%) of patients with a diagnosis of cancer.

The informed consent document also contained the option for participants to serve as coauthors for the creation of the final manuscript. This was offered to eliminate the risk of misrepresentation of panelist quotes and discussion points regarding potentially sensitive and controversial topics. All panelists agreed to serve as a coauthor for the final manuscript. This study was exempt from institutional review board review.

Question Formulation and Selection

A request for question suggestions for the panel discussion was distributed on the OncANP online forum. OncANP members were encouraged to share the question submission request with any colleague in the field of naturopathic oncology. OncANP members were encouraged to develop questions that (1) discuss the main topics of the panel, which are ethics, philosophy, and research development of naturopathic oncology; (2) integrate these main topics with a subset of topics relevant to the field of naturopathic oncology, including, but not limited to, clinical approach, research, and future goals of the field; (3) are open-ended, possibly multifaceted, controversial, and able to initiate thorough debate among the physicians on the panel. A total of 45 questions were submitted for consideration for question selection. Questions were categorized to assist in selecting topics of interest as identified by the physicians in the field of naturopathic oncology. The research team indicated their preferred questions and topics, and the principal investigator for the study selected and formatted the top 6 questions that were used in the discussion.

Panel Discussion and Answering Protocol

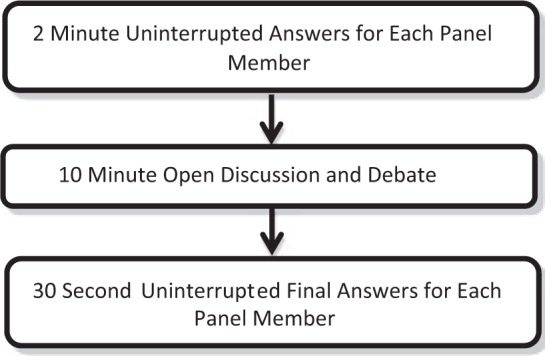

The discussion was recorded on 2 Zoom H4M Handy audiorecorders and a single synchronized MP3 file was created. Transcription of the audiorecording was completed with the assistance of medical students at the National College of Natural Medicine (NCNM). The Delphi director reviewed the answering protocol prior to initiating the in-person discussion, read the questions to the panel, called out the order for answering, and cut off participants when their answering time limit was reached. Figure 1 provides an overview of the answering protocol used for each of the 6 questions.

Figure 1.

Answering protocol flowchart.

The order of answering for the initial 2-minute answers and 30-s final answers were selected at random. None of the panelists answered first to more than 1 question, and 2 panel members did not answer first to any of the 6 questions. The answering protocol was designed to maintain the Delphi methodology of answer, discussion, and reanswer. This permits panelists to support, contradict, or alter their answer or any answer presented by the panel. The answering methodology encouraged the collective group to identify key topics for answers.

Content Analysis

Thematic coding was completed on the audio transcription to identify key topics. Three research assistants individually identified panelist answers to each question on a blinded transcript. Each answer or discussion point provided by a panel member was placed into a theme/topic. The number of times the theme was mentioned and the number of panel members to mention the theme were documented. Interrater reliability was also calculated, which is the percentage agreement of identified themes among the 3 research assistants completing the thematic coding. The themes were ranked systematically and based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme. Thematic coding identified between 12 and 35 different themes per question. The top 5 themes for each question were used to create a consensus survey using REDCap software. The panelists were asked to individually rank their level of agreement for each theme. Consensus percentage was calculated based on the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), or completely disagree (0%). To establish consensus, a cutoff percentage of 75% was set by the research team prior to the distribution of the consensus survey.

Results

Tables 5 to 11 list the top 5 themes identified for each question, followed by quotes for clarification of each theme. Random numerical identifiers were assigned to the panelists to prevent identification of quotes.

Table 5.

Content Analysis, Question 1A, Consensus.a

| Theme/Topic | Mentions, Total, n (SD)b | Mentions, Panel Members, Percentage (SD)c | Consensus (%)d | Interrater Reliability (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The importance of promoting/supporting quality of life for the patientA,B | 9.7 (0.58) | 6.7 (0.58) | 96.9 | 100 |

| Focusing on whole person careC | 7.3 (1.53) | 5.3 (1.15) | 90.6 | 100 |

| Naturopathic oncology is integrative care, not alternative care. There is a necessity to work with conventional standard of careD,E | 5.7 (1.53) | 5.7 (1.53) | 81.3 | 100 |

| The importance of using diet as therapyF | 4 (0.00) | 4 (0.00) | 90.6 | 100 |

| The importance of maintaining naturopathic principlesG | 4 (1.73) | 3.3 (1.15) | 84.4 | 100 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

All data are averaged from the thematic identification of 3 blinded research assistants. Ranking of themes is systematic and primarily based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme.

Average number of theme mentions during discussion.

Average number of panel members who verbalized the theme during discussion.

The percentage of consensus for each theme among panel members. Consensus was the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), completely disagree (0%).

The interrater reliability among the 3 research assistants who completed the thematic coding.

Table 11.

Content Analysis, Question 6.a

| Theme/Topic | Mentions, Total, n (SD)b | Mentions, Panel Members, Percentage (SD)c | Consensus (%)d | Interrater Reliability (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians need to practice at their level of training and expertiseA,B | 5.33 (1.53) | 3.67 (0.58) | 100 | 100 |

| Primary care NDs can comanage cancer patients with MD or ND oncologistsC | 5.00 (1.73) | 3.67 (0.58) | 78.1 | 100 |

| Increasing therapeutic knowledge requires specialization in naturopathic medicineD | 3.33 (2.08) | 3.00 (1.73) | 93.8 | 100 |

| There is a necessity for appropriate training for NDs to recognize signs and symptoms of cancerE | 2.67 (1.15) | 2.67 (1.15) | 100 | 100 |

| Until more NDs are available, safe generalized care by PCPs is necessaryF | 2.33 (0.58) | 1.33 (0.58) | 75 | 100 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; PCP, primary care practitioner.

All data are averaged from the thematic identification of 3 blinded research assistants. Ranking of themes is systematic and primarily based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme.

Average number of theme mentions during discussion.

Average number of panel members who verbalized the theme during discussion.

The percentage of consensus for each theme among panel members. Consensus was the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), completely disagree (0%).

The interrater reliability among the 3 research assistants who completed the thematic coding.

Table 6.

Content Analysis, Question 1B, Controversy.a

| Theme/Topic | Mentions, Total, n (SD)b | Mentions, Panel Members, Percentage (SD)c | Consensus (%)d | Interrater Reliability (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturopathic oncology can be used as an alternative to conventional standard of careH | 7.3 (1.53) | 5.7 (0.58) | 78.1 | 100 |

| The degree to which the practitioner relies on evidenced-based medicine/importance of using evidence-based medicineI | 6.3 (0.58) | 5.3 (0.58) | 84.4 | 100 |

| The degree to which NDs consider herb/drug interactions and contraindications to conventional standard of careJ | 5.3 (0.58) | 5.0 (0.00) | 87.5 | 100 |

| The necessity for naturopathic oncology credentialing/additional training requirements for naturopathic oncologyK | 3.7 (1.53) | 3.7 (1.53) | 78.1 | 100 |

| Dispensary ethicsL | 3 (0.00) | 3 (0.00) | 56.3 | 100 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

All data are averaged from the thematic identification of 3 blinded research assistants. Ranking of themes is systematic and primarily based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme.

Average number of theme mentions during discussion.

Average number of panel members who verbalized the theme during discussion.

The percentage of consensus for each theme among panel members. Consensus was the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), completely disagree (0%).

The interrater reliability among the 3 research assistants who completed the thematic coding.

Table 7.

Content Analysis, Question 2.a

| Theme/Topic | Mentions, Total, n (SD)b | Mentions, Panel Members, Percentage (SD)c | Consensus (%)d | Interrater Reliability (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicate the strength and weakness of evidence to patient/informed consentA | 6.3 (2.89) | 4.7 (1.53) | 93.8 | 100 |

| Consider the harm to benefit ratioB | 4.3 (1.53) | 4.0 (1.00) | 96.9 | 100 |

| Ensure appropriate interpretation of research evidenceC,D | 3.3 (1.53) | 3.0 (1.00) | 93.8 | 100 |

| Using clinical and anecdotal evidenceE | 3.0 (1.00) | 2.0 (0.00) | 78.1 | 100 |

| Apply naturopathic philosophy to available researchF | 2.7 (1.15) | 2.3 (1.53) | 59.4 | 100 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

All data are averaged from the thematic identification of 3 blinded research assistants. Ranking of themes is systematic and primarily based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme.

Average number of theme mentions during discussion.

Average number of panel members who verbalized the theme during discussion.

The percentage of consensus for each theme among panel members. Consensus was the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), completely disagree (0%).

The interrater reliability among the 3 research assistants who completed the thematic coding.

Table 8.

Content Analysis, Question 3.a

| Theme/Topic | Mentions, Total, n (SD)b | Mentions, Panel Members, Percentage (SD)c | Consensus (%)d | Interrater Reliability (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The ethical responsibility falls on educating patients/informed consentA | 13.0 (2.65) | 7.3 (0.58) | 96.9 | 100 |

| The patient’s choice must ultimately be honoredB | 4.3 (1.53) | 3.3 (1.53) | 93.8 | 100 |

| There is a responsibility for the physician to stay educatedC | 2.7 (1.53) | 3.7 (0.58) | 93.8 | 100 |

| It is important to understand the underlying issues to patients’ decisionsD | 2.7 (0.58) | 2.7 (0.58) | 96.9 | 100 |

| It is important to consider adjusting therapiesE | 2.7 (1.53) | 2.3 (1.15) | 84.4 | 100 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

All data are averaged from the thematic identification of 3 blinded research assistants. Ranking of themes is systematic and primarily based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme.

Average number of theme mentions during discussion.

Average number of panel members who verbalized the theme during discussion.

The percentage of consensus for each theme among panel members. Consensus was the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), completely disagree (0%).

The interrater reliability among the 3 research assistants who completed the thematic coding.

Table 9.

Content Analysis, Question 4.a

| Theme/Topic | Mentions, Total, n (SD)b | Mentions, Panel Members, Percentage (SD)c | Consensus (%)d | Interrater Reliability (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies demonstrating an integrative approach/whole systems approachA,B | 4.67 (0.58) | 4.00 (0.00) | 96.9 | 100 |

| Case studies/case series by ND oncologistsC | 3.67 (1.15) | 3.67 (1.15) | 75 | 100 |

| Data on recurrence rates, longitudinal observational studiesD | 3.33 (0.58) | 3.00 (1.00) | 87.5 | 100 |

| Data on survival outcomes, longitudinal observational studiesE | 2.67 (1.15) | 3.33 (1.15) | 90.6 | 100 |

| Research on specific cancers and therapies, standardized protocolsF | 2.67 (0.58) | 2.00 (0.00) | 75 | 100 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

All data are averaged from the thematic identification of 3 blinded research assistants. Ranking of themes is systematic and primarily based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme.

Average number of theme mentions during discussion.

Average number of panel members who verbalized the theme during discussion.

The percentage of consensus for each theme among panel members. Consensus was the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), completely disagree (0%).

The interrater reliability among the 3 research assistants who completed the thematic coding.

Table 10.

Content Analysis, Question 5.a

| Theme/Topic | Mentions, Total, n (SD)b | Mentions, Panel Members, Percentage (SD)c | Consensus (%)d | Interrater Reliability (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is a necessity for foundational education of naturopathic physicians in oncologyA | 8.7 (0.58) | 4 (0.00) | 93.8 | 100 |

| Establishing safety in practice guidelines/patient safetyB | 6.3 (1.15) | 5.7 (0.58) | 93.8 | 100 |

| Considering naturopathic licensure laws/scope of practice of NDs in various locationsC | 4 (1.73) | 4 (1.73) | 75 | 100 |

| Sustainable treatments for the patientD | 3.7 (1.15) | 3.7 (1.15) | 75 | 100 |

| Maintaining naturopathic principlesE | 3.7 (0.58) | 3.3 (0.58) | 71.9 | 100 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

All data are averaged from the thematic identification of 3 blinded research assistants. Ranking of themes is systematic and primarily based on interrater reliability, followed by total number of mentions, and finally considering the number of panel members to mention each theme.

Average number of theme mentions during discussion.

Average number of panel members who verbalized the theme during discussion.

The percentage of consensus for each theme among panel members. Consensus was the average of the following survey choices: completely agree (100%), mostly agree (75%), somewhat agree (50%), mostly disagree (25%), completely disagree (0%).

The interrater reliability among the 3 research assistants who completed the thematic coding.

Question 1: What are 3 topics in naturopathic oncology that generate consensus among practicing physicians? What are 3 issues in naturopathic oncology that generate the most controversy?

Question 1A Quotes

A Panelist 6: “The ultimate benefits of naturopathic oncology are to improve the person’s quality of life.”

B Panelist 4: “First, I think this has been said before, but there’s an inherent value to naturopathic oncology care, that what we do has a profound impact on quality of life.”

C Panelist 2: “I do think that there is a perspective that whole person care is critically important, looking at mental, emotional, spiritual issues.”

D Panelist 6: “I think most in naturopathic oncology would agree that naturopathic oncology is typically integrative and not alternative to the standard of care.”

E Panelist 4: “I agree that one of the consensus is that naturopathic oncology is inherently integrative and that our role is to play within the system to help support people going through that, and not as a source of alternative care.”

F Panelist 2: “I think the importance of diet and dietary choices is something that there is a fair amount of consensus around.”

G Panelist 5: “One of the things I think we all agree on is that we need to stick to our principals. Even though we call it oncology, we’re not focusing on disease. We’re following like — — says, truly individual promoting, health restoration, not just disease treatment.”

Question 1B Quotes

H Panelist 6: “As far as controversies, the first one, that naturopathic oncology can be used as an alternative form of treatment to standard of care. I think 2 people have already alluded to that.”

I Panelist 2: “In terms of issues that are controversial, I also had in my mind to separate out naturopathic oncologists, that is people who are primarily seeing cancer patients, from the general practicing ND. I think those answers would be very different. In my book, it has to do with the degree of which we rely on evidence”

J Panelist 7: “The field of herb/drug interactions and contraindications, given the sort of overall gray area of the literature in general, the need to make clinical decisions without sufficient evidence is another area of controversy.”

K Panelist 4: “I think there’s a controversy around the level of training that’s required to provide good naturopathic oncology care, and at what point does that become and allow someone to effectively treat people with cancer?”

L Panelist 5: “I think dispensary ethics is something that is constantly being thrown out as, is it ethical for us to dispense product?”

Question 2: How do you approach research evidence that contradicts other research when making a clinical decision? How do you approach research evidence (or lack of evidence) that contradicts your clinical experience and/or personal philosophy to the practice of naturopathic oncology? Provide specific examples.

Question 2 Quotes

A Panelist 2: It really involves communication with the patient and a very open, honest, dialogue about what we know, and more importantly, what we don’t know.”

B Panelist 4: “And really try to include a healthy consideration of the harm-benefit ratio that is applicable to that particular therapy.”

C Panelist 5: “Certainly I’ve got a lot of benefit from taking a course from Cochrane Review Group on interpreting research. I really think that should be in every school; something we all know how to do.”

D Panelist 7: “That actually is one of my pet peeves, is naturopathic doctors not reading the primary source of the research, the full article, themselves, and relying on somebody’s analysis that immediately dismisses the evidence because they don’t like it, and finds all the faults of the study. I think that it needs to be weighed much more carefully.”

E,F Panelist 4: “I think while within the context of limited evidence, and it’s being framed, I think we really have to rely also on the art of the practice of naturopathic medicine, and be guided by clinical experience, because there is a limit to what we can derive from the information.”

Question 3: What ethical responsibility does a naturopathic oncologist have when a patient’s wishes are contrary to evidence or contrary to the physician’s philosophy? Please provide a real or hypothetical example of how this situation should be managed.

Question 3 Quotes

A Panelist 6: “I think a naturopathic physician’s primary responsibility is to educate their patient on their disease, their treatment options, and to ultimately support their informed decisions.”

B Panelist 6: “If as their physician you feel comfortable that the patient is making this decision from a place of knowledge, and not necessarily from a place of fear or misinformation, or even worse yet, altered mental capacity, I think that patient’s choice must ultimately be honored.”

C Panelist 1: “To be a really super, like superhero, naturopathic oncologist in the ethical arena, I think that we have to respect the patient’s wishes, create a safe environment to educate them, but in order to do that, we have to stay really educated ourselves, which is I think where it also gets challenging. This is a big big big deal, this is a big load to carry.”

D Panelist 2: “As an example, I had a patient who was refusing conventional care for Hodgkin’s disease, which is a potentially curable situation, because he was afraid of the impact on his quality of life. I had to point out that if he dies he won’t have any quality of life. It’s understanding what is the underlying issue there.”

E Panelist 7: “I would also like to say that I don’t think that it always has to be black and white. That’s what I talk to a lot of patients about. I mean surgery is black and white, but once you’ve gone down that road, you’ve gone down that road. But most everything else, you can opt out. You could try that AI that you absolutely hate the side effects of. If you hate it, stop it. If you hate it we might be able to try and find other conventional therapy alternatives. If you hate chemotherapy after one cycle, it can be changed. I think that sometimes patients feel like that road is this like absolute once I cross over, I’m committed. It doesn’t have to be.”

Question 4: What research evidence will make the most difference to the clinical practice of naturopathic oncology? What type of research is needed to benefit the field of naturopathic oncology? Explain how and why.

Question 4 Quotes

A Panelist 6: “In my opinion, the research that’s needed most, that will make the most difference in the practice and I think general acceptance of naturopathic oncology, is a systems approach. Naturopathic medicine teaches us to treat the whole person, to address their main health determinants such as diet, lifestyle, exercise, stress management, with a multitude of modalities that we have that are at our disposal. I think a study of one vitamin, or amino acid, or herb at a time, although critical and essential, it does not represent the practice of naturopathic oncologists and I think we need to be doing systems approach studies.”

B Panelist 1: “Clearly an integrative approach needs to be . . . we need studies to demonstrate what we all know to be true, that combining our therapies with standard of care, conventional standard of care, is successful in terms of quality of life outcomes.”

C Panelist 3: “I propose 4 projects that we can do now that will take us far. One is the publication of case studies by individual naturopathic oncologists should be highly fostered. These can document for the rest of us what may have helped or did not, and that’s the best kind of data at present to help us reach consistency consensus in treatment.”

D Panelist 2: “I think the primary area of value is in the area of prevention of recurrence. Patients who have had disease, they have been treated, they have no evidence of disease, and the impact of naturopathic medicine creating that long-term, durable, recurrence-free survival.”

E Panelist 1: “I think naturopathic oncology research does, and should continue to, include longitudinal observational studies of survival and recurrence rates. I think that’s really the best outcome measure for our research.”

F Panelist 2: “And I do think that we do need to work on creating standardized protocols for specific kinds of conditions.”

Question 5: What criteria should determine the priorities for the development of “best practice” guidelines with respect to naturopathic oncology?

Question 5 Quotes

A Panelist 8: “I really believe that best practice should start at the level of the initial education.”

B Panelist 2: “That has to be the number one overriding issue in any kind of practice guidelines, is that practitioners need to be safe.”

C Panelist 8: “I think best practice guidelines have to take into account the geographical location and the difference in scope of practice in most of our practitioners in North America.”

D Panelist 5: “Something that we have to keep in mind, is this really sustainable for this patient? Are they committed? Do they have the support and do they have the resources?”

E Panelist 5: “I think these foundation principles, Docere, first do no harm, and those sorts of things are what we always have to work from, and as long as we stick to that, we are doing good medicine.”

Question 6: What symptoms or diagnoses should naturopathic doctors who have no additional oncology training be able to treat? For example, is it ethical for primary care NDs to treat side-effects of chemotherapy and/or directly treat the cancer?

Question 6 Quotes

A Panelist 6: “A doctor ethically should only treat those conditions that they feel sufficiently competent to treat.”

B Panelist 7: “I think that it’s a judgment call and it’s a case by case basis, but I agree that physicians over all ND, MD, DO need to practice to their level of training and expertise.”

C Panelist 7: “I think that there are a variety of scenarios where naturopathic doctors who were not primarily treating cancer could comanage a patient. I think ideally they would potentially even be co-comanaging a patient with a naturopathic doctor.”

D Panelist 3: “So alas, if it wasn’t clear already the era of specialization of naturopathic medicine is upon us. The reason there are specialists in allopathic medicine is because no one can know it all.”

E Panelist 4: “I believe that there really needs to be good training for NDs to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of cancer.”

F Panelist 1: “I think the realistic view of this is that until we have enough numbers to do it like the oncologists and the GPs do, we are going to have to come up with some ways to enable, facilitate, safe care at the GP level in our profession while we are building the numbers. I mean, I just don’t see how we can get around that.”

Discussion

The modified Delphi protocol was successful in recruiting a panel of experts, obtaining relevant questions for discussion, and applying thematic coding to develop consensus regarding key themes in ethics, philosophy, and research development in the field of naturopathic oncology. In addition, each of the 6 questions successfully initiated and maintained discussion. The panelists chose to use their full 2-minute initial answer, with one exception, which was because of confusion over the question. Three of the questions maintained discussion for the full 10 minutes. One question maintained discussion for 9 minutes, one for 7 minutes, and one for 6 minutes. The panelists did not always choose to use their 30-s time period for final thoughts. Of the 35 themes presented in this article, 32/35 reached the consensus cutoff of 75%. This indicates that the thematic coding was successful in identifying themes of high relevance and agreement among the panel.

Numerous themes were obtained for each question, and each theme can provide its own relevant and applicable information for application to the development of naturopathic oncology. This Delphi panel is the first systematic approach to consensus development using nominated experts in the field of naturopathic oncology; therefore, the themes were intentionally created to be short and concise to provide simplistic foundational statements from which a field of practitioners can reference. In addition, creating basic foundational statements provides individuals unfamiliar with naturopathic oncology the ability to grasp the ideas that drive the clinical practice and research development of naturopathic oncologists.

A few key topics appear throughout the panel discussion. First is the topic of integration with conventional oncology. Consensus was reached by the panel of nominated experts that integration and collaboration with physicians throughout conventional oncology is important for the quality of patient care. The panel agrees integration is important, but they also agree that it is a point of controversy in the field. Not all naturopathic oncologists agree that integration is necessary for quality cancer care. However, because the themes of this Delphi panel originate from the ideas of experts nominated by physicians in the field, these ideas should theoretically represent the majority of practicing naturopathic oncologists. Therefore, the field appears to lean toward integration as a vital component of patient care.

Additional key topics identified include an emphasis on safe, patient-centered care. The improvement of quality of life, recurrence rates, and survival outcomes are also mentioned throughout the discussion as areas of focus for naturopathic oncologists. The lack of extensive evidence for all therapies currently used by naturopathic oncologists creates controversy in the ethics and philosophy of clinical approach. This leads back to the topic of integration and whether or not adequate evidence exists using naturopathic therapies to safely treat cancer patients without integration with conventional oncology. According to the themes and consensus derived from the panel, integration is currently the best approach for cancer patients. However, cancer patients also seek naturopathic oncologists because they refuse conventional treatment. The panelists’ consensus states that there is a responsibility of the physician to ensure that the patient is fully educated on their specific case, including strengths and weaknesses of all available research, prior to refusal of conventional care. If the patient is able to make an informed decision, then the final decision is ultimately up to the patient.

The importance of educating patients on available evidence requires a certain level of competency of the emerging field of naturopathic/CAM oncology research. This addresses another key discussion topic regarding requirements of additional training and specialization of naturopathic oncologists. Currently, naturopathic physicians trained as primary care practitioners provide supportive care for cancer patients. However, their conventional primary care practitioner counterparts will refer patients to conventional oncologists if a cancer diagnosis is suspected. Panel consensus indicates that additional training and specialization is needed to adequately treat and support cancer patients with naturopathic medicine, and therefore, naturopathic primary care physicians should comanage cancer patients with either a qualified naturopathic oncologist or conventional oncologist, or they should receive additional specialized training if they desire to treat cancer patients.

There are several limitations worth considering regarding this modified protocol. Research conducted on the efficacy of the Delphi method in developing consensus found that in the majority of studies, anonymous, individual answers have higher rates of accuracy than face-to-face discussion.2 There are inherent limitations to any qualitative research approach, including limited opportunities to apply statistical significance and quantify the data. Limitations specific to this modified Delphi protocol include lack of anonymity in the panel member and question nomination process. Although the highest level of anonymity was attempted, the use of e-mail prevented fully anonymous submission. In addition, there is a limitation arising from the necessity to have multiple experts in the same location for an in-person discussion: it prohibits participation of experts unable to travel for the discussion. There is a chance for bias among the research team who selected the panelists and formulated the questions. Bias may also be introduced when converting the transcription into categorical themes. The necessity for interpretation of the transcript potentially increases error in thematic coding.

The application of this Delphi model is an appropriate method to use considering situational appropriateness. An annual conference provides an ideal setting for continual modified Delphi panels to further assist the field of naturopathic oncology in clarifying unknown or debated topics. Recommendations for future Delphi panels using a similar protocol include the use of online databases for anonymous submission of panelist nominations and question suggestions. In addition, the use of categorical analysis software can greatly decrease the required time for thematic coding and content analysis. Feedback from the naturopathic oncology Delphi panelists was overwhelmingly positive. A few panelists mentioned the need for additional systematic interprofession dialogue. In addition, the answering protocol used received approval by the panelists for its ability to encourage the formation of an answer while also permitting the panelists to change, alter, support, and debate answers.

Conclusion

Naturopathic oncology is an emerging field with strong potential for expansion as the desire for integrative and complementary medicine increases in the field of oncology. Foundational research, such as the naturopathic oncology Delphi panel, provides a platform for identification of key topics regarding ethics, philosophy, and research development. A few key topics identified from this study are the importance of safe, integrated, patient-centered care as well as the need for additional training and specialization of naturopathic oncology. The authors hope that this study provides a clinically applicable resource for practicing naturopathic oncologists as well as being a source of information regarding naturopathic medicine for professionals in the field of oncology and the general public.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals for their assistance with this project: Brice Thompson, James Munro, Adrianne Sebastian, Kara Crisp, Nicolette Callan, Desta Golden, Steve Chamberlin, Corey Murphy, Steve Fong, and Steve Dehner.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Jacob Hill held a paid post- doctorial research position at the Helfgott Research Institute (academic institution) while completing this study. The creation of this study was supported by an NIH R-CAMP R25 research grant. Grant Number: NIH 5R25AT002878.

References

- 1. Rand Corp. Delphi method. http://www.rand.org/topics/delphi-method.html. Accessed April 21, 2014.

- 2. Dalkey NC. The Delphi method: an experimental study of group opinion. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_memoranda/RM5888/RM5888.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2014.

- 3. Cancer Treatment Centers of America. Naturopathic medicine for cancer treatment. http://www.cancercenter.com/treatments/naturopathic-medicine/. Accessed September 19, 2014.

- 4. Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, Greisinger A, Singletary SE. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2505-2514. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10893280. Accessed May 25, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. OncANP. http://oncanp.org/find_fabno.html. Accessed April 24, 2014.

- 6. National University of Health Sciences. Doctor of naturopathic medicine program. http://www.nuhs.edu/admissions/naturopathic-medicine/. Accessed April 24, 2014.

- 7. Leaver CA, Miller-Davis C, Wallen GR. Naturopathic management of females with cervical atypia: a Delphi process to explore current practice. Integr Med Insights. 2013;8:9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shinto L, Calabrese C, Morris C, et al. A randomized pilot study of naturopathic medicine in multiple sclerosis. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:489-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christman A, Schrader S, John V, Zunt S, Maupome G, Prakasam S. Designing a safety checklist for dental implant placement: a Delphi study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:131-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Broomfield D, Humphris GM. Using the Delphi technique to identify the cancer education requirements of general practitioners. Med Educ. 2001;35:928-837. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11564196. Accessed May 25, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown R, Butow P, Butt D, Moore A, Tattersall MH. Developing ethical strategies to assist oncologists in seeking informed consent to cancer clinical trials. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:379-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Falzarano M, Pinto Zipp G. Seeking consensus through the use of the Delphi technique in health sciences research. J Allied Health 2013;42:99-105. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23752237. Accessed May 25, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Application to Practice, 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis J, Zayat E, Urton M, Belgum A, Hill M. Communicating evidence in clinical documentation. Aust Occup Ther J. 2008;55:249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hobbelen JSM, Koopmans RTCM, Verhey FRJ, Van Peppen RPS, de Bie RA. Paratonia: a Delphi procedure for consensus definition. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2006;29:50-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holmes WM, Scaffa ME. An exploratory study of competencies for emerging practice in occupational therapy. J Allied Health 2009;38:81-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacDonald C, Cox P, Bartlett D, Houghton P. Consensus on methods to foster physical therapy professional behaviors. J Phys Ther Educ. 2002;16:26-36. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bissett M, Cusick A, Adamson L. Occupational therapy research priorities in mental health. Occup Ther Health Care. 2002;14:1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen M, Harle M, Woll A, Despa S, Munsell M. Delphi study of nursing research priorities. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:1011-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wikeby M, Pierre BL, Archenholtz B. Occupational therapists’ reflection on practice within psychiatric care: a Delphi study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2006;13:151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Biondo PD, Nekolaichuk CL, Stiles C, Fainsinger R, Hagen NA. Applying the Delphi process to palliative care tool development: lessons learned. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:935-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conklin MH, Desselle SP. Development of a multidimensional scale to measure work satisfaction among pharmacy faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Falzarano M, Zipp GP. Perceptions of mentoring of full-time occupational therapy faculty in the United States. Occup Ther Int. 2012;19:117-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perry A, Morris M, Unsworth C, et al. Therapy outcome measures for allied health practitioners in Australia: the AusTOMs. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Falzarano M. Describing the occurrence and influence of mentoring for occupational therapy faculty members who are on the tenure track or eligible for reappointment. http://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/365. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- 27. De Villiers MR, de Villiers PJT, Kent AP. The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Med Teach. 2005;27:639-643. Accessed April 9, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glässel A, Kirchberger I, Linseisen E, Stamm T, Cieza A, Stucki G. Content validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for stroke: the perspective of occupational therapists. Can J Occup Ther. 2010;77:289-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glässel A, Kirchberger I, Kollerits B, Amann E, Cieza A. Content validity of the extended ICF core set for stroke: an international Delphi survey of physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1211-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raine S. Defining the Bobath concept using the Delphi technique. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11:4-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]