Abstract

Purpose. Many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) during or after their therapy. Because little is known about CAM in palliative care, we conducted 2 surveys among patients and professionals in the palliative setting. Participants and methods. Patients of a German Comprehensive Cancer Center were interviewed, and an independent online survey was conducted among members of the German Society for Palliative Care (DGP). Results. In all, 25 patients and 365 professional members of the DGP completed the survey (9.8% of all members); 40% of the patients, 85% of the physicians, and 99% of the nurses claimed to be interested in CAM. The most important source of information for professionals is education, whereas for patients it is radio, TV, and family and friends. Most patients are interested in biological-based methods, yet professionals prefer mind-body-based methods. Patients more often confirm scientific evidence to be important for CAM than professionals. Conclusions. To improve communication, physicians should be trained in evidence for those CAM methods in which patients are interested.

Keywords: palliative care, complementary therapies, neoplasm, information seeking behavior, attitude of professionals

Introduction

In Germany, 40% of cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) at some time during or after therapy.1 According to a widespread definition, complementary methods are used in addition to, whereas alternative methods are used instead of, conventional medicine.2 In a recent European survey, 36% of all patients admitted using CAM. Mostly, they were using biological-based methods such as phytotherapy, supplements, and medical teas. Women with breast or gynecological cancers more often use CAM than other patients.3 In a review on women with gynecological cancers, 60% to 90% of patients were found to use CAM. Also in this review, biological-based methods were the preferred treatments.4 In some recent studies in Germany, similarly high rates have been published. Of patients consulting a counseling unit on CAM at a comprehensive cancer center, 42% reported using trace elements, 34% vitamins, and 38% other supplements. Chinese herbs were used by 19%.5

In a survey on patients during radiotherapy, 90% of breast cancer patients, 42% of those with lung cancer, and 50% of those with rectal cancer disclosed CAM and supplement use. Also in this survey, most patients used some kind of substances—for example, supplements.6 In all surveys from Europe and Germany mind-body techniques, meditation, and relaxation are used less frequently.1-6 Patients with advanced cancer use CAM more often than patients with nonadvanced cancers.6-10 In a palliative care setting, two-thirds of the participants reported using CAM.11

Patients most often seek information from family and friends and less frequently from the media and the Internet.5,12 In international studies, physicians, and especially the oncologist, are mentioned less frequently as sources of information.3,4 There are different reasons why patients do not address their physician: doubts about his/her expertise or willingness to answer questions on this topic or the fear of getting a negative or prohibitory answer.12 In Germany, however, physicians are considered an important source of information.13 This may be because of the acceptance and the high number of physicians with a specialization in naturopathy or other complementary disciplines.13

In oncology, CAM not only has beneficial effects but also carries risks such as side effects or interactions—for example, between phytotherapy and anticancer drugs. 14,15 Only a few studies mention possible interactions, and side effects are usually only dealt with in case reports. Yet an analysis of possible interactions in outpatients of a certified breast center in Germany points to a high risk of interactions of biological-based CAM methods, such as Chinese medical herbs, with chemotherapy or endocrine therapy.16 In the palliative setting, patients who are desperately looking for a chance of cure may even replace palliative care by an alternative treatment.

Little is known about the use of and attitudes toward CAM in the palliative setting. We conducted 2 surveys in the palliative care setting: one focusing on patients and relatives and the other focusing on physicians, nurses, and other professionals in palliative care.17,18

The main risks associated with CAM substances are side effects or interactions. Better communication on CAM may help avoid these risks in palliative care if physicians are acquainted with the necessary knowledge and help patients understand these risks. The purpose of this study is to compare the attitudes of patients and professionals as described in both studies and to find out whether there is accordance or not. In the latter case, this would point to obstacles in communication between both.

Participants and Methods

In 2 independent studies, members of the German Society for Palliative Care (DGP) and patients of the palliative care unit or patients on palliative care of the adjacent ward for radiotherapy of the Comprehensive Cancer Center in Frankfurt/Main (Germany) were interviewed about their interest in and their use of CAM. In both interviews, we used standardized questionnaires that have been developed by our working group (for a description of this process see previous publications).17,18 Neither questionnaire was validated.

Samples

All members (n = 3740) of the DGP were invited via e-mail to participate in an Internet-based survey, which was available for 3 months in 2011. The access was only possible with a link sent in the e-mail. Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous. The members of the DGP came from different professions; mostly they were physicians and nurses.

Between May 2011 and May 2012, consecutive patients of the palliative care unit or the adjacent ward for radiotherapy of the Comprehensive Cancer Center in Frankfurt/Main were asked to participate in the study. The sample size had been calculated with the following assumption, based on data from the literature: a total of 80% of patients are interested in CAM, 7% are not interested in CAM, and 13% score “I don’t know.”

Assuming a P < .05 as acceptable and a study with 80% power, the sample size was calculated as 25 patients. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria listed below and gave informed consent were asked to take part in the study. After written informed consent had been given by the patient, structured interviews were held.

Inclusion criteria were the following: 18 years of age or more, histologically proven cancer of any type, and advanced stage of cancer. The patient had to have been admitted into residential palliative care for symptom control and informed of the palliative situation of his/her illness. Furthermore, patients had to be able to follow a structured interview in German. For all patients, written informed consent was mandatory. Patients were excluded if they were not able to concentrate on the interview (10-15 minutes) because of their illnesses, medications, or other reasons.

Questionnaires

The basic questionnaire was developed by the working group, Prevention and Integrative Oncology (PRIO) of the German Cancer Society, and has been used in different settings for patients as well as professionals.5 All questions either provide a list of possible answers or ask for a rating using mostly a 4-point Likert scale.

For patients, the questionnaire was structured as follows:

Demographic data and data on lifestyle in the past

Perception of reason for being ill with cancer (lay etiological concept)

Questions on interest in and use of CAM

The patients were interviewed personally by one of the authors (MP).

For professionals, the questionnaire was adapted by members of the working group, Complementary Medicine of the DGP, and the working group, Clinical Research of the DGP.

The questionnaire for professionals basically consisted of 3 parts:

Personal data

Personal attitude toward CAM and personal experiences

Professional attitude toward CAM

In this questionnaire, we asked the participants to distinguish between complementary treatments (taken in parallel with palliative therapy to alleviate side effects or symptoms) and alternative treatments (used instead of a conventional treatment). The questionnaire was programmed as an online questionnaire (using Unipark/Questback)19 and sent to the participants as a link. The questionnaires included a list of different CAM methods that are generally used most frequently by patients with cancer; this list was based on published surveys on user behavior in Germany.5,6,20

The patients were asked to indicate which methods they were interested in (possible answers: “yes,” “no,” or “do not know”), if they were using one of these at the time of the survey (possible answers: “yes” or “no”), and if they were satisfied with the method. The physicians as well as the nurses were asked if they recommended any of these methods to their patients, advised against it, or did not give any advice.

Statistics

In the descriptive analysis, median, range, and relative frequencies were used. Analyses of frequencies and cross-tables with χ2 tests were done using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.21 In this study, we focused on those questions that are the same or similar in both groups in order to compare patients and professionals. Only completely filled-in questionnaires were analyzed.

Ethical Approval

The study on the patients was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Results

At the time of the survey, the DGP had about 3740 members, and 690 (18.5%) members filled in the online questionnaire; 365 members of the DGP (9.8%) fully completed the questionnaire and were included in this study. In total, 58.6% of the 365 DGP members were physicians, and 29.2% were nurses. Among the patients, 40% were female and 60% were male. Among the physicians, 45.8% were female and 54.2% were male, whereas 78% of nurses were female and 22% were male. The average age of the patients was 64.8 years, of the physicians 49 years, and of the nurses 44 years.

In all, 40% of patients claimed to be interested in CAM, as did 84.6% of physicians and 99.1% of nurses; 68% of patients had already used CAM. In the group of professionals, 75.2% of physicians and 93.6% of nurses stated that they had personally used CAM before.

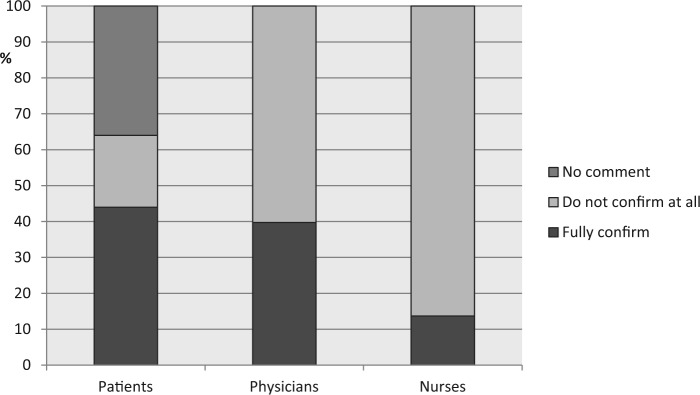

Education and training were the most important sources of information for professionals, whereas radio, TV, and family and friends were the most important for patients (Figure 1). Apart from these sources used only by one of the groups, patients on palliative care as well as professionals most often used journals (patients, 28%; professionals, 48%). Only 12% of patients utilized the Internet, whereas 37.6% of nurses (P = .045) and 31.1% of physicians (P = .014) quoted the Internet as a source of information.

Figure 1.

Sources of information about complementary and alternative medicine used by the participants (missing bars: this item was not included in the questionnaire for this population).

It is remarkable that only 8% of the patients sought a physician’s advice about CAM. Among physicians, 34.6% used the expertise of their specialized colleagues, and nurses referred to the specialized physician in 22% of the cases.

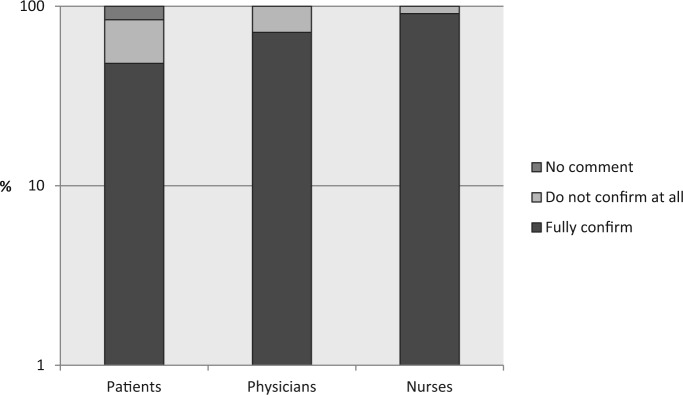

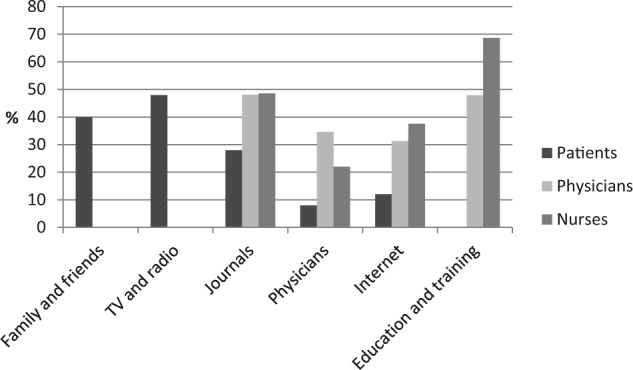

In both questionnaires, the participants were asked to rate their agreement or dissent with different statements asking about effects on patients and evidence concerning CAM. Two statements were similar in both questionnaires (Figures 2 and 3). Most participants agreed that CAM might have positive effects on a patient. No significant differences could be found between physicians and patients (71.5% vs 57.1%), whereas nurses confirmed this statement significantly more often than patients (90.8% vs 57.1%, P < .001).

Figure 2.

Vote on the sentence: “As science does not know much on these methods, I do not recommend them/I do not use them.”

Figure 3.

Vote on the sentence: “These methods have positive effects on patients.”

Regarding the statement, “As science does not know much on these methods, I do not use them,” 68.8% of patients agreed with it; in contrast, 39.7% (P = .023) of physicians and only 13.8% (P < .001) of nurses agreed with this statement.

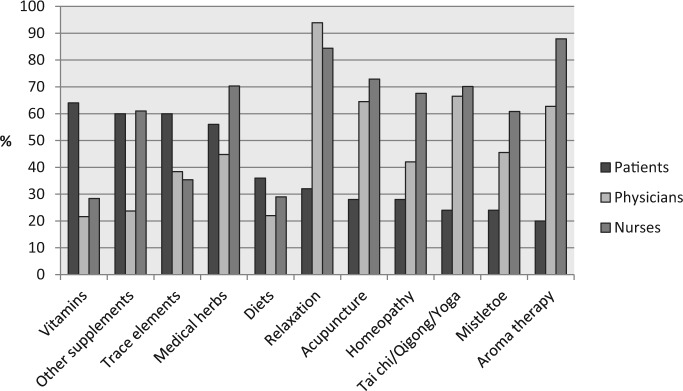

The list of CAM methods provided to the participants was similar in both groups (in fact, the list for the professionals was longer and included additional techniques, mostly from nursing—eg, aromatherapy or reflexology). We compared those CAM methods that were listed for patients as well as for professionals. Figure 4 compares the most often used or recommended CAM methods.

Figure 4.

Complementary and alternative medicine methods most often used by patients or recommended by physicians and nurses.

The number of patients who actually used CAM was 40%. Patients preferred biological-based methods such as trace elements (64%), vitamins (60%), other supplements (60%), medical herbs (64%), and diets (32%). In contrast, physicians preferred mind-body methods such as relaxation (94%), meditation (75%), tai chi/qigong/yoga (66.5%), or spiritual care (82%) and acupuncture (64.5%). The top 5 recommendations by nurses included aromatherapy (88%), relaxation (84%), meditation (82%), spiritual care (73%), and acupuncture (70%). A significant difference for all methods was found between recommendation by physicians or nurses and actual use by the patients (P < .001). Methods that were highly recommended by the physicians often met with a far lower interest on the part of the patients, especially methods belonging to the body-mind complex: Relaxation techniques and physical exercise were recommended by more than 80% of physicians, but only 32.0% of patients were interested in these methods (P < .001). Other methods were highly recommended by physicians as well such as acupuncture (64.5% vs 28.0%, P < .001) and anthroposophic medicine (30.2% vs 4.0%, P < .001), respectively, but were met with low interest on the part of the patients.

Discussion

As both our surveys have shown, CAM is of high relevance for patients as well as for professionals in palliative care. Acceptance is high in the different professional groups, and patients are highly interested in CAM. Yet there are substantial differences between the 2 groups when considering data on or use of and recommendation for CAM methods.

The preferred sources of information are different for patients and for professionals, the latter preferring education and training, the former radio, TV, and the family. Because of these differences, communication on CAM may be further complicated because both groups do not know much regarding the information the other group has. Journals and the Internet are shared sources of information used by professionals and patients. Thus, professionals engaging in patient counseling on CAM might screen popular journals and the Web to learn about information on CAM presented. The Internet will gain even more importance in the near future. One decisive problem with this source of information is the diversity of quality and reliability. Regarding cancer and CAM, most information on German Web sites is of low quality.22 In a review in 2008, the same has been shown internationally.23 As a consequence, it is not easy for patients or for professionals to select reliable information in the complicated field of CAM.23,24 Both groups could benefit by comprehensive and reliable information on the benefits and risks of these methods.25 In the meantime, several US comprehensive cancer centers and the National Cancer Institute26 are providing evidence-based information on CAM on their Web sites. Furthermore, several German national guidelines on cancer offer information on CAM.27

Both patients as well as professionals are convinced that CAM may have benefits for the patients. Yet, interestingly, patients are more skeptical than nurses and physicians (91% of nurses, 72% of physicians, and only 48% of patients fully agree). In addition, patients quote low scientific evidence of CAM methods as a reason for not using CAM more often than professionals do (patients 44%, nurses 14%, physicians 40%). Because there are no comparable data from cancer patients in less-advanced stages, we are not able to decide whether this skepticism is a result of the disappointment of patients who have tried diverse CAM methods and whose cancer has still advanced or whether patients in general have a high belief in scientific evidence and know about the problem of low levels of evidence for CAM.

The comparison between professionals’ recommendations and patients’ use reveals important differences. Professionals prefer mind-body techniques such as tai chi/qigong/yoga, meditation or relaxation techniques, and spiritual care. The patients in the palliative ward are hardly in a physical condition to practice tai chi, qigong, or yoga. In this case, the question is whether a recommendation would be realistic. To our knowledge, there is no evidence that one of these methods has any positive effect on patients with terminal stage of cancer. In contrast, patients on palliative care prefer biological-based methods. In fact, the preference of patients for biological-based CAM is well known,1,3,5,6 and this has also been shown for patients taking part in phase I studies who mostly are in a far advanced situation.28,29 The rationale as to why these methods are less often recommended by professionals is unknown. Missing evidence as well as a fear of side effects and interactions may be reasons. Yet, if this were true, the rate of recommendations for medical herbs should have been even lower. Another explanation might be that professionals rate pills as an additional burden to patients who have to take several drugs anyway. In contrast, the administration of non–substance-based methods might be regarded as some kind of “care” and contact, which may induce a beneficial effect. In spite of all these considerations, some discrepancy between the patients’ interests and the recommendations given by professionals remains.

When interpreting the data, it is important to consider the limitations of the surveys: One survey was conducted nationwide, whereas the other was a single-center approach. Furthermore, it is not known whether the patients disclosed all CAM use to the interviewer. On the other hand, patients were asked by a student not working on the ward, and the answers to the interview were concealed to the staff on the ward. For the professionals, only a small part of the members of the DGP took part. We cannot exclude the hypothesis that participants were more inclined to recommend CAM than nonparticipants.

Conclusions

Professionals as well as patients are highly interested in CAM. Yet today, communication on CAM in the palliative care setting is scarce. An important means to improve this communication might be improving knowledge of professionals about the evidence of CAM methods in which patients are mostly interested. Because user behavior has been stable for decades, the amount of knowledge required is manageable.3,6,13,16 Furthermore, physicians should take into account their patients’ desire for evidence-based information even in the field of CAM.

Evidence-based recommendations for the methods patients prioritize provided in the framework of the national cancer guidelines would be a highly effective tool to distribute this knowledge and to provide easy open access.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the German Society for Palliative Medicine (DGP) and the Working Group Research of the DGP, especially Prof Dr Ostgathe, University Erlangen, for their contribution to the conception of the questionnaire and help with providing the questionnaire to the members of the DGP.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: MP and CC contributed equally to this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G, Less D, Ritter E, Zwahlen M. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:187-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Cancer Institute. Complementary and alternative medicine. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cam. Accessed March 28, 2015.

- 3. Molassiotis A, Fernadez-Ortega P, Pud D, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:655-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eschiti VS. Lesson from comparison of CAM use by women with female-specific cancers to others: it’s time to focus on interaction risks with CAM therapies. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:313-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huebner J, Micke O, Muecke R, et al. User rate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) of patients visiting a counseling facility for CAM of a German Comprehensive Cancer Center. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:943-948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Micke O, Bruns F, Glatzel M, et al. Predictive factors for the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in radiation oncology. Eur J Integr Med. 2009;1:22-30. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soellner W. Attitude toward alternative therapy, compliance with standard treatment, and need for emotional support in patients with melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:316-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soellner W, Maislinger S, DeVries A, Steixner E, Rumpold G, Lukas P. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients is not associated with perceived distress or poor compliance with standard treatment but with active coping behavior: a survey. Cancer. 2000;89:873-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hlubocky FJ, Ratain MJ, Wen M, Daugherty CK. Complementary and alternative medicine among advanced cancer patients enrolled on phase I trials: a study of prognosis, quality of life, and preferences for decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:548-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klafke N. Prevalence and predictors of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by men in Australian cancer outpatient services. Annals Oncol. 2012;23:1571-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buentzel J, Glatzel M, Bruns F, Kisters K. Use of complementary/alternative therapy methods by patients with breast cancer. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2003;10:304-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:90-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muenstedt K, Entezami A, Wartenberg A, Kullmer U. The attitudes of physicians and oncologists towards unconventional cancer therapies (UCT). Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:2090-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colalto C. Herbal interactions on absorption of drugs: mechanims of action and clinical risk assessment. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:207-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shord SS, Shah K, Lukose A. Drug-botanical interactions: a review of the laboratory, animal and human data or 8 common botanicals. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8:208-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeller T, Muenstedt K, Stoll C, et al. Potential interactions of complementary and alternative medicine with cancer therapy in outpatients with gynecological cancer in a comprehensive cancer center. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:357-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Conrad AC, Muenstedt K, Micke O, Prott FJ, Muecke R, Huebner J. Attitudes of members of the German Society for Palliative Medicine toward complementary and alternative medicine for cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1229-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Paul M, Davey B, Senf B, et al. Patients with advanced cancer and their usage of complementary and alternative medicine. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:1515-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Questback. People matter: get their insight. http://www.questback.com/de/. Accessed March 28, 2015.

- 20. Buessing A, Cysarz D, Edelhäuser F. Inanspruchnahme unterstützender komplementärmedizinischer Verfahren bei Tumorpatienten in der späteren Phase. Dtsch Z Onkol. 2007;39:162-168. [Google Scholar]

- 21. soft32. IBM SPSS statistics 20.0. http://ibm-spss-statistics.soft32.com/. Accessed March 28, 2015.

- 22. Liebl P, Seilacher E, Koester MJ, Stellamanns J, Zell J, Huebner J. What cancer patients find in the Internet: the visibility of evidence-based patient information. Analysis of information on German websites. Oncol Res Treat. 2015;38:212-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brauer JA, El Sehamy A, Metz JM, Mao JJ. Complementary and alternative medicine and supportive care at leading cancer centers: a systematic analysis of websites. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:183-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Broom A, Tovey P. The role of the Internet in cancer patients’ engagement with complementary and alternative treatments. Health (London). 2008;12:139-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boddy K, Ernst E. Review of reliable information sources related to integrative oncology. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:619-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Cancer Institute. Cancer information summaries. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam. Accessed March 28, 2015.

- 27. Huebner J, Follmann M. Complementary medicine in guidelines of the German Guideline Program in Oncology: comparison of the evidence base between complementary and conventional therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;130:1481-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dy GK, Bekele L, Hanson LJ, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by patients enrolled onto phase I clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2000;22:4810-4815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stephan S, Naing A, Hong DS. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients seen in phase I clinical trials program [abstract 9091]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl). [Google Scholar]