Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The use of dietary supplements has increased and is associated with adverse effects. Indications for use include recreation, body image concerns, mood enhancement, or control of medical conditions. The risk of adverse effects may be enhanced if agents are used improperly. The objective of this study was to determine the frequency of abuse and misuse of 4 dietary substances among adolescents reported nationally to poison centers. Secondary outcomes included an assessment of medical outcomes, clinical effects, location of treatments provided, and treatments administered.

METHODS

This descriptive retrospective review assessed data concerning the use of garcinia (Garcinia cambogia), guarana (Paullinia cupana), salvia (Salvia divinorum), and St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) among adolescents reported nationally to poison centers from 2003 to 2014. Adolescents with a singlesubstance exposure to one of the substances of interest coded as intentional abuse or misuse were included. Poison center calls for drug information or those with unrelated clinical effects were excluded. Data were collected from the National Poison Data System.

RESULTS

There were 84 cases: 7 cases of Garcinia cambogia, 28 Paullinia cupana, 23 Salvia divinorum, and 26 Hypericum perforatum. Garcinia cambogia was used more frequently by females (100% versus 0%), and Paullinia cupana and Salvia divinorum were used more frequently by males (61% versus 36% and 91% versus 9%, respectively). Abuse, driven by Salvia divinorum, was more common overall than misuse. Abuse was also more common among males than females (p <0.001). Use of these agents fluctuated over time. Overall, use trended down since 2010, except for Garcinia cambogia use. In 62 cases (73.8%), the medical outcome was minor or had no effect or was judged as nontoxic or minimally toxic. Clinical effects were most common with Paullinia cupana and Salvia divinorum. Treatment sites included emergency department (n = 33; 39.3%), non-healthcare facility (n = 24; 28.6%), admission to a health care facility (n = 8; 9.5%), and other/unknown (n = 19; 22.6%).

CONCLUSIONS

Abuse and misuse of these dietary supplements was uncommon, and outcomes were mild. Further research should be performed to determine use and outcomes of abuse/misuse of other dietary supplements in this population.

Keywords: abuse, adolescents, dietary supplements, herbal, Poison Center

Introduction

The use of dietary supplements among both adults and pediatrics has increased over the years, as reflected in part by the number of telephone calls to poison centers nationwide regarding these agents. Between 2004 and 2014, the total number of calls for both adults and pediatric patients regarding dietary supplements rose almost 40%, from 24,842 to 34,569 calls.1,2 The use of dietary supplements among the general population has been described previously.3,4 The continued use and popularity of dietary supplements in recent years may be due to various factors, including fear of adverse events associated with prescription medications, cost of prescription medications, over-the-counter availability of dietary supplements, and perceptions that dietary supplements are “natural” or “herbal” and are therefore safe to use.5

Although some dietary supplements may have acceptable safety profiles, many are associated with adverse events and drug-drug interactions.6–9 The use of dietary supplements among the pediatric population raises particular concern because of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics differences between children and adults and the potential for the presence of additives or adulterants in dietary supplement products.10,11 Despite the potential harm associated with use, the use of dietary supplements among the adolescent population has been reported; however, these studies are often limited to specific adolescent populations.12–17 Furthermore, the harmful effects of dietary supplements may be enhanced if the agents are abused or misused.

The 4 supplements of interest (Table 1) were chosen because adolescents are using these substances for indications including weight loss (garcinia, Garcinia cambogia; guarana, Paullinia cupana), recreation (salvia, Salvia divinorum), and control of medical conditions, such as depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (St John's wort, Hypericum perforatum).5,18–23 In addition, these supplements have been shown to be associated with adverse effects and/or drug-drug interactions.

Table 1.

Dietary Supplements

Garcinia cambogia is derived from a fruit-bearing tree found in tropical Asia, Africa, and Polynesia. The dried rind of the fruit is used for a multitude of culinary purposes and as a fixative during silk dyeing. The principal acid in Garcinia cambogia is (-)-hydroxycitric acid. This acid limits the availability of acetyl-coenzyme A units required for fatty acid synthesis and lipogenesis, thereby, slowing down the production of fatty acids and reducing fat production and storage, hence, its use as a weight-loss aid.24

Paullinia cupana is derived from a plant native to the Amazon basin.25 The seeds of this plant have a long history of use by Amazonian tribes as a stimulant, assumed to reflect the presence of caffeine.26,27 Paullinia cupana also includes other potentially psychoactive components, such as saponins and tannins.25 It is commonly used as a weight-loss agent and to improve cognitive performance.28

Salvia divinorum is an herb that is native to Mexico and has been used for centuries because of its mind-altering effects. The active component is salvinorin A, which gives the agent hallucinogenic properties. Traditionally, Salvia divinorum was used by the Mazatec people to facilitate spiritual encounters; however, recreational use of Salvia divinorum has increased worldwide during the past decade.29–31

Hypericum perforatum is derived from a perennial plant originally native to Europe and Asia. Although the mechanism of action is not well defined, it may affect the transmission of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin. This agent is a top-selling herbal product used in a variety of homeopathic preparations but is best known for its use in the treatment of mild-to-moderate depressive disorders.32

The aim of this study was to determine the frequency of abuse and misuse among adolescents of Garcinia cambogia, Paullinia cupana, Salvia divinorum, and Hypericum perforatum reported to poison centers and to examine the medical outcomes, clinical effects, location of treatments provided, and associated treatments in relation to the use of these specific dietary supplements.

Materials and Methods

Study Design. Data on specific dietary supplements were requested from the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) National Poison Data System (NPDS) for the period of January 1, 2003, through December 31, 2014. The AAPCC, an organization of all poison centers in the United States, manages the NPDS, the data warehouse for poison centers. Poison centers submit data to NPDS via online, near–real-time data-collection systems. Poison centers respond to questions from the public and health care professionals. The NPDS was queried for cases involving single substance exposure to Garcinia cambogia, Paullinia cupana, Salvia divinorum, and Hypericum perforatum. Cases were included if the patient was an adolescent (defined as 13–19 years old), and the reason for substance use was coded as intentional abuse or intentional misuse. The NPDS defines intentional abuse as the improper or incorrect use of a substance in an attempt to gain a high, euphoric effect, or some other effect, whereas intentional misuse is the improper or incorrect use of a substance for a reason other than the pursuit of a psychotropic effect.33 Exclusion criteria included telephone calls related to drug-information requests and cases with coingested substances. Only coded data were available to the investigators, not free text fields.

Deidentified data were received from the NPDS in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) format. Data were analyzed for age, gender, case counts by year, clinical effects, management sites, treatments, and coded outcomes. The primary outcome of this study was to assess the frequency of abuse and misuse of specific dietary supplements (Paullinia cupana, Garcinia cambogia, Salvia divinorum, and Hypericum perforatum) in the adolescent population reported nationally to poison centers from 2003 to 2014. The secondary outcomes were to assess the medical outcomes, related clinical effects, management sites, and treatments administered in relation to the dietary supplements of interest. Poison center coding (using national coding guidelines) of known medical outcomes include no effect, minor effect, moderate effect, major effect, and death.33 Examples of minor effects include mild gastrointestinal symptoms (self-limited, no dehydration), drowsiness, and sinus tachycardia without associated hypotension. Examples of moderate effects include gastrointestinal symptoms (with associated dehydration), acid-base disturbances, and hypotension that rapidly respond to treatment. Examples of major effects include cardiovascular instability, ventricular tachycardia with hypotension, and renal failure with clinical evidence.

Cases not followed to a known outcome are coded as either judged as nontoxic, minimal clinical effects possible or judged as potentially toxic. The definitions of those outcomes are derived from a national coding guideline.33 Those coded as judged as nontoxic are patients who were not followed because, per clinical judgment, the exposure was likely to be nontoxic because the amount implicated in the exposure was insignificant. In those cases, there was reasonable certainty that the patient would not experience any clinical effect from the exposure. Those coded as minimal clinical effects possible were patients who, based on clinical judgment, had an exposure likely to result in minimal clinical toxicity of a trivial nature. In those cases, there was reasonable certainty that the patient would experience no more than a minor effect. Last, those coded as judged as potentially toxic were patients who were lost to follow-up and, per clinical judgment, had a significant exposure that may result in a moderate, major, or fatal outcome. Medical outcomes are determined by specialists in poison information when cases are closed. In this study, management site was defined as the highest level of care that the patient received and includes non-healthcare facility (non-HCF), treated and released from the emergency department (ED), admitted to a non-critical care, critical care, or psychiatry floor (admitted), or other/lost to follow-up/refused referral/unknown (unknown). This study was deemed exempt by the university's institutional review board before initiation.

Statistical Analysis. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and analyzed with χ2 test using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics. There were 84 cases of abuse or misuse involving the 4 dietary supplements of interest from 2003 to 2014. The most commonly implicated dietary supplement was Paullinia cupana, and the least commonly implicated dietary supplement was Garcinia cambogia (Table 2). Overall, abuse or misuse of those agents was more common among males (n = 52; 61.9%), and there were differences in use by sex, with Paullinia cupana and Salvia divinorum used primarily by males, and Garcinia cambogia used primarily by females The median age in the total population was 16 years (Table 2). In general, abuse of the dietary supplements of interest was more frequent than misuse. When stratified by gender, the use (including both abuse and misuse) of these substances was more common in males (p <0.001) (Table 2). Furthermore, abuse of these substances was more common in males (p <0.001) (Table 3). There was no difference in occurrence of abuse or misuse of these agents when stratified by geographic location (Table 4). Ingestion was the most common route (n = 68; 81% of the cases). However, for Salvia divinorum, 70% of cases were inhalation/nasal exposures.

Table 2.

Demographic Data

Table 3.

Abuse Versus Misuse

Table 4.

Geographic Location

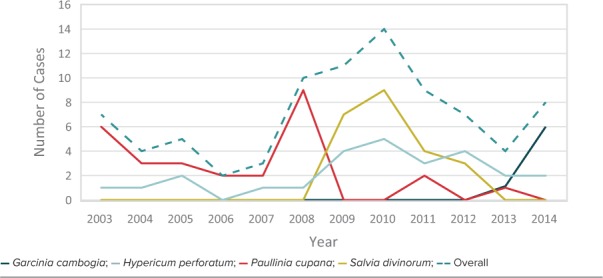

Primary Outcome. The frequency of abuse/misuse of the dietary supplements of interest fluctuated over time, with a peak use around 2010. The incidence of abuse/misuse of the dietary supplements trended down overall since 2010, with the exception of Garcinia cambogia in 2014, during which most Garcinia cambogia cases occurred (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends of abuse/misuse over time.

Secondary Outcomes. Secondary outcomes included assessing the medical outcomes, related clinical effects, management sites, and treatments administered in relation to the dietary supplements of interest.

Medical Outcomes. In 62 cases (73.8%), the medical outcome was minor or no effect or was judged nontoxic or minimally toxic. Hypericum perforatum and Salvia divinorum were more likely to have known medical outcomes; however, there were no serious effects or deaths associated with any of the dietary supplements during the study period (Table 5).

Table 5.

Medical Outcomes

Related Clinical Effects. Related clinical effects were most common with Paullinia cupana and Salvia divinorum. The most commonly related clinical effects seen with Paullinia cupana were vomiting and agitation/irritability, whereas confusion and drowsiness/lethargy were seen most commonly with Salvia divinorum (Table 6). For other dietary supplements, most clinical effects were reported in a few patients.

Table 6.

Related Clinical Effects

Management Site. The most common management site was the ED (n = 33; 39.3%). About one-third of patients were managed at a non-HCF, typically in their own residence. Approximately one-fourth of the patients were lost to follow-up or had an unknown management site. A small portion of patients were admitted to an HCF, either to a medicine floor, intensive care unit, or psychiatric floor for management of dietary supplement exposure (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Management site.

Treatments Provided. Few patients received pharmacologic treatment, including benzodiazepines (n = 6; 7%), presumably for agitation because no seizure occurrences were reported. Among the 23 cases of Salvia divinorum exposures, 4 patients (17.4%) received a benzodiazepine. One of the 84 patients (1.2%) received an antiemetic with a Paullinia cupana exposure.

Discussion

It is important, in general, to explore the use of dietary supplements because these agents do not require approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before marketing. In October 1994, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) was signed into law.34 Under that law, a manufacturer is responsible for determining that their dietary supplement is safe, that any claim or representation made is substantiated by sufficient evidence, and that such claims are not false or misleading. However, the DSHEA does not require that a dietary supplement be approved by the FDA before manufacturing and does not mandate that manufacturers report adverse effects or events to a public health agency.5,35 Therefore, the onus is placed upon the FDA to prove that a supplement is harmful, rather than on the manufacturer to prove their dietary-supplement product is safe and effective. Data concerning adverse events related to dietary supplements are, at times, captured through poison center data.5

Although other studies have examined the use of dietary supplements among the general population or at the state-level, few have looked at the use of these substances among adolescents at the national or international level.3–5,13,15–17,30,35–44 This study examined the use of Garcinia cambogia, Paullinia cupana, Salvia divinorum, and Hypericum perforatum among the adolescent population at a national level.

Adolescents are able to start making their own independent healthcare decisions and are using dietary supplements for indications including recreation, control of medical conditions, and weight loss, especially with body image concerns in the age of peer and social media influences.5,13,18–23,30,31,37,38 Adolescents are also less likely to respond to concerns of potential harm from dietary supplement use, particularly if the product is touted as having immediate benefits.45 As previously described, it is well known that certain dietary supplements are often associated with adverse events, which may even lead to a ban of the agent, such as with Ephedra.18 Furthermore, adolescents and adults alike may not consider dietary supplements to be medications or drugs and may not inform their physician or pharmacist if they choose to use such substances.3,4,19,38,40 Also, physicians and pharmacists may not be routinely asking about the use of such substances among their patients.46 This places the patient at risk for adverse effects and potential drug-drug interactions. In addition, abuse or misuse of dietary substances has been associated with the use of other agents, including cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs.13,47 All of those agents carry their own risk of negative clinical effects.

Similar to other data that show that males may be more likely to abuse substances, this study also demonstrated sex differences.48,49 This finding was somewhat unexpected, however, because it was theorized that abuse/misuse of these specific agents might be more common among females because 2 of the dietary supplements of interest (Garcinia cambogia and Paullinia cupana) are used frequently for weight loss, an indication for which females are more likely to use substances.12,19,38,39,50,51 However, cases of Salvia divinorum drove the high amount of abuse among patients, with approximately 96% of Salvia divinorum cases occurring because of abuse. The most common use of Salvia divinorum was for recreation to achieve a euphoric effect. Therefore, it was not unexpected that misuse of that agent was low because there is no known therapeutic use for Salvia divinorum.21 Furthermore, it is not surprising that the use of Salvia divinorum was greater among males because males have been shown to be more likely to use substances recreationally in an attempt to seek a euphoric effect or to enhance the effect of other substances.52

In general, use of these dietary supplements of interest fluctuated over time, with an overall decrease in use seen after 2010. Based on previous estimates that show up to 28.6% of adolescents admit to using dietary supplements, it was interesting that only 84 cases were captured nationally during that time frame.13 The most likely reason for this is that this study included only singlesubstance exposures, which greatly limited the number of cases because abuse/misuse of multiple substances is often more common than singlesubstance abuse/misuse.21,52

Throughout the study period, there were spikes in the use of each of the agents. The first notable increase was with Paullinia cupana in 2007. It is possible that adolescents were seeking alternative weight-loss supplements after the ban of Ephedra in 2004, leading to that increase in use.13,18 The increase in Paullinia cupana use may have been delayed after the Ephedra ban because there were other weight-loss supplements, such as bitter orange, also available during the period between 2004 and 2007. The use of Salvia divinorum was not seen in this study population until 2009. One possible explanation is due to mainstream media coverage of this agent around that time. Finally, although the use of Hypericum perforatum remained relatively steady throughout the study period, the use of Garcinia cambogia increased in 2014. Interestingly, a popular entertainment figure first promoted Garcinia cambogia on their television show in 2013.53 Despite the peaks in use of specific agents over the period of the study, general use of those agents has trended down since 2010, with the exception of Garcinia cambogia. That may be due in part to increased awareness of the potentially adverse effects associated with dietary supplements and/or an overall decline in calls to poison centers.

The clinical effects associated with the dietary supplements of interest were infrequent and mild. There are several possible explanations for that finding. First, only singlesubstance exposures were included. If multisubstance exposures were included, additional clinical effects may have been seen, but it would not have been possible to determine which effects were attributable to the substances of interest. Next, we were unable to verify the amount of each substance that the patient was exposed to, so it is possible that the exposure quantity was too little to cause clinical effects.

Paullinia cupana was associated with more clinical effects than Garcinia cambogia was. Although both are used for weight-loss purposes, that finding is likely explained by the fact that Paullinia cupana contains caffeine, which has central nervous system and cardiovascular stimulant effects.19 In contrast, Garcinia cambogia contains hydroxy citrate, which lacks central nervous system and cardiovascular stimulant effects and works instead by altering carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.20,54 That being said, it is difficult to make overarching conclusions about clinical effects associated with those agents as a whole, given the small number of cases.

Limitations for this study include that the accuracy and completeness of the data relies on the correct coding within the NPDS database by poison center specialists. Reporting to poison centers is voluntary, so NPDS does not capture all exposures. Only cases involving a call to a poison center were captured, and the indication for dietary supplement use was not verified. Next, this study only assessed the abuse and misuse of singlesubstance exposures, which limited the number of total cases and made it challenging to comprehensively assess trends over time in abuse/misuse of the substances of interest. Although abuse of agents is often multisubstance, multisubstance exposures were excluded because the coded data does not provide sufficiently specific information to differentiate which agent the adolescent was abusing or misusing.21,52 The exclusion of multisubstance exposures also allowed for a more accurate assessment of the clinical effects related to each specific agent. Next, when assessing management site, many patients were already en route to an HCF when the poison center was called; thus, it is difficult to ascertain which patients among that subset may have been well enough to have been managed in a non-HCF versus being triaged to an ED. Last, this study looked at outcomes related to 4 specific dietary supplements of interest; therefore, trends in abuse and misuse of other substances among adolescents were not assessed.

Conclusions

The frequency of abuse/misuse of the dietary supplements for this study fluctuated over the study period, with relatively few of these singlesubstance exposures. Differences is sex were evident, with males more likely to abuse dietary supplements. Clinical effects were generally mild, and most patients were managed in a non-HCF or ED. Further research should be conducted to assess the abuse/misuse of other dietary supplements among the adolescent population as well as multisubstance exposures with these same dietary supplements to more accurately assess trends in use over time.

Acknowledgments

This project was presented as a poster at the United HealthSystem Consortium Pharmacy Council Meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana, in December 2015. A platform presentation was conducted at the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group annual meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, in April 2016.

Abbreviations

- AAPCC

American Association of Poison Control Centers

- ED

emergency department

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- HCF

health care facility

- NPDS

National Poison Data System

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria. Dr Biggs had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclaimer The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; http://www.aapcc.org) maintains the national database of information logged by the country's 57 Poison Centers (PCs). Case records in this database are from self-reported calls: they reflect only information provided when the public or health care professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g., an ingestion, inhalation, or topical exposure, etc), or request information/educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is not able to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centers. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCs, and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s).

Copyright Published by the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group. All rights reserved. For permissions, email: matthew.helms@ppag.org

REFERENCES

- 1. Watson WA, Litovitz TL, Rodgers GC, . et al. 2004 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers toxic exposure surveillance system. Am J Emerg Med. 2005; 23 5: 589– 666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, . et al. 2014 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' national poison data system (NPDS): 32nd annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015; 53 1: 962– 1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kennedy J. Herb and supplement use in the US adult population. Clin Ther. 2005; 27 11: 1847– 1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, . et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998; 280 18: 1569– 1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dennehy CE, Tsourounis C, Horn AJ.. Dietary supplement-related adverse events reported to the California Poison Control System. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005; 62: 1476– 1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barrett B, Kiefer D, Rabago D.. Assessing the risks and benefits of herbal medicine: an overview of scientific evidence. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999; 5 4: 40– 49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pies R. Adverse neuropsychiatric reactions to herbal and over-the-counter “antidepressants.” J Clin Psychiatry. 2000; 61 11: 815– 820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abebe W. Herbal medication: potential for adverse interactions with analgesic drugs. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002; 27 6: 391– 401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Izzo AA, Ernst E.. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: an updated systematic review. Drugs. 2009; 69 13: 1777– 1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tomassoni AJ, Simone K.. Herbal medicines for children: an illusion of safety? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001; 13 2: 162– 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ernst E. Herbal medicines for children. Clin Pediatr. 2003; 42 3: 193– 196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu C, Wang C, Kennedy J.. The prevalence of herb and dietary supplement use among children and adolescents in the United States: results from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Complement Ther Med. 2013; 21 4: 358– 363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yussman SM, Wilson KM, Klein JD.. Herbal products and their association with substance use in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006; 38 4: 395– 400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson KM, Klein JD.. Adolescents' use of complementary and alternative medicine. Ambul Pediatr. 2002; 2 2: 104– 110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reznik M, Ozuah PO, Franco K, . et al. Use of complementary therapy by adolescents with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002; 156 10: 1042– 1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith J, Dahm DL.. Creatinine use among a select population of high school athletes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000; 75 12: 1257– 1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Metzl JD, Small E, Levine SR, . et al. Creatinine use among young athletes. Pediatrics. 2001; 108 2: 421– 425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rogovik AL, Goldman RD.. Should weight-loss supplements be used for pediatric obesity? Can Fam Physician. 2009; 55 3: 257– 259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vitalone A, Menniti-Ippolito F, Moro PA, . et al. Suspected adverse reactions associated with herbal products used for weight loss: a case series reported to the Italian National Institute of Health. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011; 67 3: 215– 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lenz TL, Hamilton WR.. Supplement products used for weight loss. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004; 44 1: 59– 68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thornton MD, Baum CR.. Bath salts and other emerging toxins. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014; 30 1: 47– 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weber W, Stoep AV, McCarty RL, . et al. Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort) for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008; 299 22: 2633– 2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cala S, Crismon ML, Baumgartner J.. A survey of herbal use in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or depression. Pharmacotherapy. 2003; 23 2: 222– 230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jena BS, Jayaprakasha GK, Singh R, Sakariah KK.. Chemistry and biochemistry of (-)hydroxycitric acid from Garcinia. J Agric Food Chem. 2002; 50 1: 10– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Espinola EB, Dias RF, Mattei R, Carlini EA.. Pharmacological activity of guarana (Paullinia cupana Mart.) in laboratory animals. J Ethnopharmacol. 1007; 55 3: 223– 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henman AR. Guarana (Paullinia cupana var. sorbilis): ecological and social perspective on an economic plant of the central Amazon Basin. J Ethnopharmacol. 1982; 6: 311– 338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weckerle CS, Stutz MA, Baumann TW.. Purine alkaloids in Paullinia. Phytochemistry. 2003; 64 3: 735– 742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haskell CF, Kennedy DO, Wesnes KA, . et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-dose evaluation of the acute behavioural effects of guarana in humans. J Psychopharmacol. 2007; 21 1: 65– 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kelly BC. Legally tripping: a qualitative profile of salvia divinorum use among young adults. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011; 43 1: 46– 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Curie CL. Epidemiology of adolescent Salvia divinorum use in Canada. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013; 128 1–2: 166– 170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosenbaum CD, Carreiro SP, Babu KM.. Here today, gone tomorrow… and back again? a review of herbal marijuana alternatives (K2, spice), synthetic cathinones (bath salts), kratom, Salvia divinorum, methoxetamine, and piperazines. J Med Toxicol. 2012; 8 1: 15– 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barnes J, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD.. St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): a review of its chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2001; 53 5: 583– 600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. [AAPCC] American Association of Poison Control Centers. . NPDS Coding Users' Manual. Version 3.1. Alexandria, VA: AAPCC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dickinson A. History and overview of DSHEA. Fitoterapia. 2011; 82 1: 5– 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palmer ME, Haller C, McKinney PE, . et al. Adverse events associated with dietary supplements: an observational study. Lancet. 2003; 361 9352: 101– 106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haller CA, Kearney T, Bent S, . et al. Dietary supplement adverse events: report of a one-year poison enter surveillance project. J Med Toxicol. 2008; 4 2: 84– 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O'Dea JA. Consumption of nutritional supplements among adolescents: usage and perceived benefits. Health Educ Res. 2003; 18 1: 98– 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilson KM, Klein JD, Sesselberg TS, . et al. Use of complementary medicine and dietary supplements among U.S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006; 38 4: 385– 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bell A, Dorsch KD, McCreary DR, . et al. A look at nutritional supplementation use in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004; 34 6: 508– 516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trigazis L, Tennankore D, Vohra S, . et al. The use of herbal remedies by adolescents with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2004; 35 2: 223– 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gardiner P, Dvorkin K, Kemper KJ.. Supplement use growing among children and adolescents. Pediatr Ann. 2004; 33 4: 227– 232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ervin RB, Wright JD, Reed-Gillette D.. Prevalence of leading types of dietary supplements used in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Adv Data. 2004; 9 349: 1– 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Briefel RR, Johnson CL.. Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004; 24: 401– 431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seifert SM, Schaechter JL, Hershorin ER, Lipshultz SE.. Health effects of energy drinks on children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics. 2011; 127 3: 511– 528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Greene K, Krcmar M, Walters LH, . et al. Targeting adolescent risk-taking behaviors: the contributions of egocentrism and sensation-seeking. J Adolesc. 2000; 23 4: 439– 461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klein JD, Wilson KM, Sesselberg TS, . et al. Adolescents' knowledge of and believes about herbs and dietary supplements: a qualitative study. J Adolesc Health. 2005; 37 5; 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stephens MB, Olsen C.. Ergogenic supplements and health risk behaviors. J Fam Pract. 2001; 50 8: 696– 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Becker JB, Hu M.. Sex differences in drug abuse. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008; 29 1: 36– 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brady KT, Randall CL.. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999; 22 2: 241– 252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Timbo BB, Ross MP, McCarthy PV, . et al. Dietary supplements in a national survey: prevalence of use and reports of adverse events. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 106 12: 1966– 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Robinson RF, Griffith JR, Nahata MC, . et al. Herbal weight-loss supplement misadventures per a regional poison center. Ann Pharmacother. 2004; 38 5: 787– 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boys A, Marsden J, Strang J.. Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective. Health Educ Res. 2001; 16 4: 457– 469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Konstantinides A. 2016 Feb 3. Dr Oz sued for weight loss supplement he claimed was a ‘revolutional fat buster with no exercise, no diet, no effort’. Daily Mail.com. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3430075/Dr-Oz-sued-weight-loss-supplement-Garcinia-Cambogia.html. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- 54. Esteghamati A, Mazaheri T, Rad MV, . et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of obesity: a critical review. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2015; 13 2: e19678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]