Abstract

Introduction

Case-based learning (CBL) is a newer modality of teaching healthcare. In order to evaluate how CBL is currently used, a literature search and review was completed.

Methods

A literature search was completed using an OVID© database using PubMed as the data source, 1946-8/1/2015. Key words used were “Case-based learning” and “medical education”, and 360 articles were retrieved. Of these, 70 articles were selected to review for location, human health care related fields of study, number of students, topics, delivery methods, and student level.

Results

All major continents had studies on CBL. Education levels were 64% undergraduate and 34% graduate. Medicine was the most frequently represented field, with articles on nursing, occupational therapy, allied health, child development and dentistry. Mean number of students per study was 214 (7–3105). The top 3 most common methods of delivery were live presentation in 49%, followed by computer or web-based in 20% followed by mixed modalities in 19%. The top 3 outcome evaluations were: survey of participants, knowledge test, and test plus survey, with practice outcomes less frequent. Selected studies were reviewed in greater detail, highlighting advantages and disadvantages of CBL, comparisons to Problem-based learning, variety of fields in healthcare, variety in student experience, curriculum implementation, and finally impact on patient care.

Conclusions

CBL is a teaching tool used in a variety of medical fields using human cases to impart relevance and aid in connecting theory to practice. The impact of CBL can reach from simple knowledge gains to changing patient care outcomes.

Keywords: case-based learning, medical education, medical curriculum, graduate medical education

Introduction

Medical and health care-related education is currently changing. Since the advent of adult education, educators have realized that learners need to see the relevance and be actively engaged in the topic under study.1 Traditionally, students in health care went to lectures and then transitioned into patient care as a type of on-the-job training. Medical schools have realized the importance of including clinical work early and have termed the mixing of basic and clinical sciences as vertical integration.2 Other human health-related fields have also recognized the value of illustrating teaching points with actual cases or simulated cases. Using clinical cases to aid teaching has been termed as case-based learning (CBL).

There is not a set definition for CBL. An excellent definition has been proposed by Thistlewaite et al in a review article. In their 2012 paper, a CBL definition is “The goal of CBL is to prepare students for clinical practice, through the use of authentic clinical cases. It links theory to practice, through the application of knowledge to the cases, using inquiry-based learning methods”.3

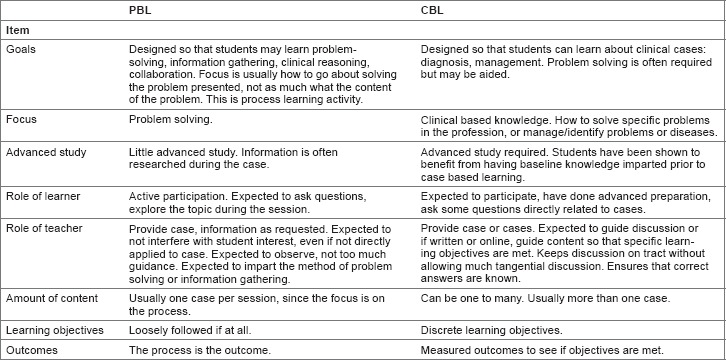

Others have defined CBL by comparing CBL to a similar yet distinct clinical integration teaching method, problem-based learning (PBL). PBL sessions typically used one patient and had very little direction to the discussion of the case. The learning occurred as the case unfolded, with students having little advance preparation and often researching during the case. Srinivasan et al compared CBL with PBL4 and noted that in PBL the student had little advance preparation and very little guidance during the case discussion. However, in CBL, both the student and faculty prepare in advance, and there is guidance to the discussion so that important learning points are covered. In a survey of students and faculty after a United States medical school switched from PBL to CBL, students reported that they enjoyed CBL better because there were fewer unfocused tangents.4

CBL is currently used in multiple health-care settings around the world. In order to evaluate what is now considered CBL, current uses of CBL, and evaluation strategies of CBL-based curricular elements, a literature review was completed.

This review will focus on human health-related applications of CBL-type learning. A summary of articles reviewed is presented with respect to fields of study, delivery options for CBL, locations of study, outcomes measurement if any, number of learners, and level of learner's education. These findings will be discussed. The rest of this review will focus on expanding on the article summary by describing in more detail the publications that reported on CBL. The review is organized into definitions of CBL, comparison of CBL with PBL, and the advantages of using CBL. The review will also examine the utility and usage of CBL with respect to various fields and levels of learner, as well as the methods of implementation of CBL in curricula. Finally, the impact of CBL training on patient and health-care outcomes will be reviewed. One wonders with the proliferation of articles that have CBL in the title, whether or not there has been literature defining exactly what CBL is, how it is used, and whether or not there are any advantages to using CBL over other teaching strategies. The rationale for completing this review is to assess CBL as a discrete mode of transmitting medical and related fields of knowledge. A systematic review of how CBL is accomplished, including successes and failures in reports of CBL in real curricula, would aid other teachers of medical knowledge in the future. Examining the current use of CBL would improve the current methodology of CBL. Therefore, the aims of this review are to discover how widespread the use of CBL is globally, identify current definitions of CBL, compare CBL with PBL, review educational levels of learners, compare methods of implementation of CBL in curricula, and review CBL reports on outcomes of learning.

Methods

A literature search was completed using an OVID© database search with PubMed as the database, 1946 to August 1, 2015. The search key words were “Case Based Learning, Medical Education”. Investigational Review Board declined to review this project as there were no human subjects involved and this was an article review. A total of 360 articles were retrieved. Articles were excluded for the following reasons: unable to find complete article on the search engine OVID, unable to find English language translation, article did not really describe CBL, article was not medically or health related, or article did not describe human beings. Articles that originated in another language but had English language translation were included.

After excluding the articles as described, 70 of these articles were selected to review for location of study, description of CBL used, human health care-related fields of study, number of students if available, topics of study, method of delivery, and level of student (eg, graduate or undergraduate). Students were considered undergraduate if they were considered undergraduate in their field. For example, medical students were considered undergraduate, because they would still have to undergo more training to become fully able to practice. If the student was in the terminal degree, then that was considered a study of graduate students. For example, nutrition students were listed as graduate students. CBL encounters for both residents and independent practitioners who were in their final training prior to practice were listed as graduates. Residents were listed under graduate medical education. If a group had already graduated, they were listed as graduates. For example, MDs who participated in a continuing medical education (CME)-type CBL were listed as graduate type of student. Articles that did not list the total number of students were included, as one of the purposes of this review was to discover how widespread the use of CBL was globally, and what types of students and types of delivery were used. By including descriptive articles that were not specific, the global use of CBL could attempt to be assessed. Including locations of studies would then help decide whether CBL was isolated from the Western countries or has it truly spread around the world.

In order to review how CBL was used, in addition to where it was used, the method of delivery was assessed. Method of delivery refers to how the total educational content was delivered. Articles were reviewed for description of exactly how material was imparted to learners. Since many authors described their learning methods in detail, an attempt was undertaken to classify these methods. Method of delivery was classified as follows: live was considered a live presentation of the case, this could be a description, a patient, or a simulated patient. Computer or web based meant that the case and content were web based. Mixed modalities meant that more than two modalities were used during presentation. For example, if an article described assigned reading, lectures, small group discussions, a live case-based session, and patient interactions, then that article would be described as mixed modalities.

Method of evaluation of the educational intervention was also reviewed. The multiple ways in which the interventions were evaluated varied. A survey of how the learners viewed the intervention was frequent. Tests of knowledge gained were frequent, and these ranged from written, to oral, to Observed Skills Clinical Examination (OSCE). Another way by which CBL intervention knowledge was evaluated was review of practice behavior in clinicians. These multiple ways to evaluate the introduction of CBL into a curriculum are summarized in a table.

Results are presented in simple frequencies and percentages. SPSS (Statistical Program for the Social Sciences, IBM) version 22 was used for analysis.

Results

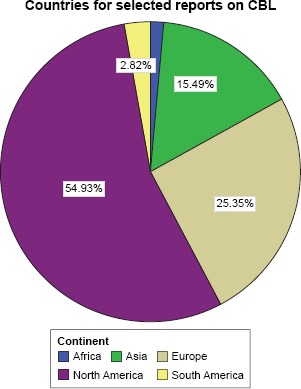

All continuously inhabited continents had studies on CBL (Fig. 1). North America is represented with the most with 54.9% of articles, followed by Europe (25.4%) and Asia, including India, Australia, and New Zealand (15.5%). South America had 2.8% and Africa had 1%.5–75

Figure 1.

CBL use worldwide.

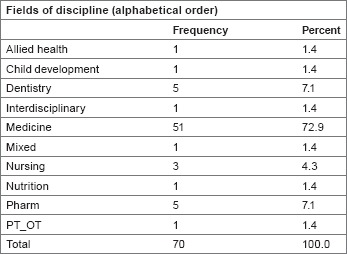

Level of education was undergraduation in 45 (64%) articles and graduation in 24 (34%) articles, with one article having both levels. One study with both faculty and residents was considered as a type of graduate education. The types of fields of study varied (Fig. 2). The most represented field was medicine including traditional Chinese medicine, with articles also on nursing, occupational therapy, allied health, child development, and dentistry. The number of students ranged from 7 to 3105 and the mean number of students was 214. One study reported on the use of teams of critical care personnel, in which it was mentioned that there were three persons per team usually. Thus, the number of students was multiplied: 40 teams x 3 = 120 in total. The total number of students were 9884 from the 46 papers that explicitly stated the number of students.

Figure 2.

Fields of study.

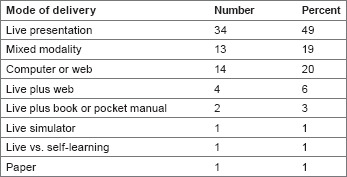

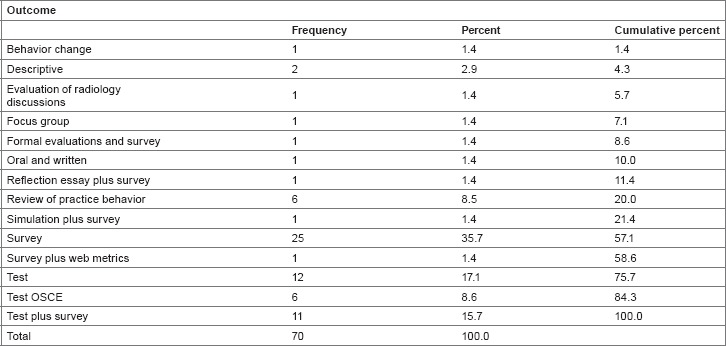

Methods of delivery also varied (Fig. 3). The most common method of delivery was live presentation (49%), followed by computer or web based (20%) and then mixed modalities (19%). Method of evaluation or outcomes was studied (Fig. 4). Survey (36%), test (17%), and test plus survey (16%) were the top three methods of evaluation of a CBL learning session. Lesser in frequency was review of practice behavior (9%), test plus OSCE (9%), and others. Review of practice behavior could include reviewing prescription writing, or in one case reviewing the number of adverse drug events reported spontaneously in Portugal.65

Figure 3.

Mode of delivery of CBL.

Figure 4.

Method of evaluation.

Discussion and Review

CBL is used worldwide. There was a large variety of fields of medicine. The numbers reported included a wide range of number of learners. Some studies were descriptive, and it was hard to know exactly how many students were involved. This problem was noted in another recent review.3 CBL was used in various educational levels, from undergraduate to graduate. The number of students ranged from very small studies of 7 students to over 3000 students. The media used to deliver a CBL session varied, from several live forms to paper and pencil or internet-based media. The outcomes measurement to review if CBL sessions were successful ranged from surveys of participants to knowledge tests to measures of patient outcomes. In order to further analyze the worldwide use of CBL, the articles are reviewed below in more detail.

Definition of CBL

CBL has been used in medical fields since at least 1912, when it was used by Dr. James Lorrain Smith while teaching pathology in 1912 at the University of Edinburgh.63,68 Thistlewaite et al3 pointed out in a recent review of CBL that “There is no international consensus as to the definition of case-based learning (CBL) though it is contrasted to problem based learning (PBL) in terms of structure. We conclude that CBL is a form of inquiry based learning and fits on the continuum between structured and guided learning.” They offer a definition of CBL: “The goal of CBL is to prepare students for clinical practice, through the use of authentic clinical cases. It links theory to practice, through the application of knowledge to the cases, using inquiry-based learning methods.”3

Another pathology article from Africa, describing a course in laboratory medicine for mixed graduate medical education (residents) and CME for clinicians, defines CBL: “Case-based learning is structured so that trainees explore clinically relevant topics using open-ended questions with well-defined goals.”7 The exploring that students or trainees do factors into other definitions. In a dental education article originating in Turkey, the authors remark: “The advantages of the case-based method are promotion of self-directed learning, clinical reasoning, clinical problem solving, and decision making by providing repeated experiences in class and by enabling students to focus on the complexity of clinical care.”8 Another definition of CBL was offered in a physiology education paper regarding teaching undergraduate medical students in India: “What is CBL? By discussing a clinical case related to the topic taught, students evaluated their own understanding of the concept using a high order of cognition. This process encourages active learning and produces a more productive outcome.”13 In an article published in 2008, regarding teaching graduate pharmacology students, CBL was defined as “Case-based learning (CBL) is an active-learning strategy, much like problem-based learning, involving small groups in which the group focuses on solving a presented problem.”45 Another study, which was from China regarding teaching undergraduate medical student's pharmacology, describes CBL as “CBL is a long-established pedagogical method that focuses on case study teaching and inquiry-based learning: thus, CBL is on the continuum between structured and guided learning.”63 It is apparent that the definition requires at least: (1) a clinical case, (2) some kind of inquiry on the part of the learner, which is all of the information to be learned, is not presented at first, (3) enough information presented so that there is not too much time spent learning basics, and (4) a faculty teaching and guiding the discussion, ensuring that learning objectives are met. In most studies, CBL is not presented as free inquiry. The inquiry may be a problem or question. Based on the fact that a problem is expected to be solved or question answered, the information covered cannot be completely new, or the new information must be presented alongside the case.

A modern definition of CBL is that CBL is a form of learning, which involves a clinical case, a problem or question to be solved, and a stated set of learning objectives with a measured outcome. Included in this definition is that some, but not all, of the information is presented prior to or during the learning intervention, and some of the information is discovered during the problem solving or question answering. The learner acquires some of the learning objectives during the CBL session, whether it is live, web based, or on paper. In contrast, if all of the information were given prior or during the session, without the need for inquiry, then the session would just be a lecture or reading.

Comparison of CBL and PBL

CBL is not the first and only method of inquiry-based education. PBL is similar, with distinct differences (Fig. 5). In many papers, CBL is compared and contrasted with PBL in order to define CBL better. PBL is also centered around a clinical case. Often the objectives are less clearly defined at the outset of the learning session, and learning occurs in the course of solving the problem. There is a teacher, but the teacher is less intrusive with the guidance than in CBL. One comparison of CBL to PBL was described in an article on Turkish dental school education: “… CBL is effective for students who have already acquired foundational knowledge, whereas PBL invites the student to learn foundational knowledge as part of researching the clinical case.” Study, of postgraduate education in an American Obstetrics and Gynecology residency, describes CBL as “CBL is a variant of PBL and involves a case vignette that is designed to reflect the educational objectives of a particular topic.”54 In an overview of CBL and PBL in a dental education article from the United States, the authors note that the main focus of PBL is on the cases and CBL is more flexible in its use of clinical material.16 The authors quote Donner and Bickley,70 stating that PBL is “… a form of education in which information is mastered in the same context in which it will be used … PBL is seen as a student-driven process in which the student sets the pace, and the role of the teacher becomes one of guide, facilitator, and resource … (p294).” The authors note that where PBL has the student as the driver, in CBL the teachers are the drivers of education, guiding and directing the learning much more than in PBL.16 The authors also note that there has not been conclusive evidence that PBL is better than traditional lecture-based learning (LBL) and has been noted to cover less material, some say 80% of a curriculum.71 It is apparent that PBL has been used to aid case-related teaching in medical fields.

Figure 5.

Differences in CBL and PBL.

Two studies highlight the advantages and disadvantages of CBL compared with PBL. Both studies report on major curriculum shifts at three major medical schools. The first study, published in 2005, reported on the performance outcomes during the third-year clerkship rotations at Southern Illinois University (SIU).19 At SIU, during the 1994–2002 school years, there was both a standard (STND) and PBL learning tract offered for the preclinical years, years 1–2. During the PBL tract, basics of medicine were taught in small group tutoring sessions using PBL modules and standardized patients. In addition, there was a weekly live clinical session. The two tracts were compared over all those years with respect to United States Medical Licensing Exam© (USMLE) test performance on Steps 1 and 2, and also overall grades and subcategories on the six third-year clerkships. So the two tracks had differing years 1–2 and the same year 3. Results noted that the PBL track had more women and older students, so these variables were set out as covariates analyzing other scores. Comparing the PBL versus STND tracks, USMLE scores were statistically equal over the years 1994–2002. PBL was 204.90 ± 21.05 and STND was 205.09 ± 23.07 (P, 0.92); Step 2 scores were PBL 210.17 ± 21.83, STND 201.32 ± 23.25 (P, 0.15). Clerkship overall scores were overall statistically significantly higher for PBL tract students in Obstetrics and Gynecology and Psychiatry (P = 0.02, P < 0.001, respectively) and statistically not different for other clerkships. Clerkship subcategory analysis demonstrated statistically significantly higher scores for PBL tract students in clinical performance, knowledge and clinical reasoning, noncognitive behaviors, and percent honors grades, with no difference in the percentage of remediations. The school decided to switch to a single-tract curriculum after 2002. The problems noted with the PBL curriculum involved recruiting PBL faculty and faculty acceptance of student interactions, and also assessment issues. Faculty had to be trained to teach in PBL, which was time consuming and interfered with the process of learning by students. In addition, some faculty felt that the teachers should determine the learner's needs and not vice versa. The PBL assessment tools were novel and not immediately accepted by the faculty.19 Other schools noted similar problems with PBL: it is different than LBL, and difficult to teach, as it is extremely learner centered. Learning objectives are essentially generated by the student, making faculty control over learning difficult. At this school, the difficulties in using PBL contributed to its abandonment as a stand-alone curriculum tract.

The difficulties in using PBL were associated with changes in other medical schools. Two medical schools in the United States, namely, University of California, Los Angeles, and University of California, Davis, changed from a PBL method to a CBL method for teaching a course entitled Doctoring, which was a small group faculty led course given over years 1–3 in both schools.4 Both schools had a typical PBL approach, with little student advance preparation, little faculty direction during the session, and a topic that was initially unknown to the student. After the shift in curriculum to CBL, there were still small group sessions, but the students were expected to do some advance reading, and the faculty members were instructed to guide or direct the problem solving. Since in both schools the students and faculty had some experience with PBL before the shift, a survey was used to assess student and faculty experiences and perceptions of the two methods. Both students and faculty preferred CBL (89% of students and 84% of faculty favored CBL). Reasons for preference of CBL over PBL were as follows: fewer unfocused tangents (59% favoring CBL, odds ratio [OR] 4.10, P = 0.01), less busywork (80% favoring CBL, OR 3.97 and P = 0.01), and more opportunities for clinical skills application (52%, OR 25.6, P = 0.002).4 In summary, these two reports indicate that while a case-oriented learning session can prepare students for both tests of knowledge and also clinical reasoning, PBL has the problems of difficult to initiate faculty or teachers in teaching this way, difficult to cover a large amount of clinical ground, and difficulty in assessment. CBL, on the other hand, has advantages of flexibility in using the case and offers the same reality base that offers relevance for the adult health-care learner. In addition, CBL appears to be accepted by the faculty that may be practicing clinicians and offers a way to teach specific learning objectives. These advantages of CBL led to it being the preferred method of case-related learning at these two large medical schools.

Advantages of CBL and deeper learning

Another touted advantage of CBL is deeper learning. That is, learning that goes beyond simple identification of correct answers and is more aligned with either evidence of critical thinking or changes in behavior and generalizability of learning to new cases. Several articles described this aspect of CBL. One article was set at a tertiary care hospital, the Mayo Clinic, and was a teaching model for quality improvement to prevent patient adverse events.33 The students were clinicians, and the course was a continuing education or postgraduate course. The authors in the Quality Improvement, Information Technology, and Medical Education departments created an online CBL module with three cases representing the most common type of patient adverse events in internal medicine. The authors use Kirkpatrick's outcomes hierarchy to assess the level of critical thinking after the CBL intervention. Kirkpatrick's outcomes hierarchy is based on four levels: the first, reaction of learner to educational intervention, the second, actual learning: acquiring knowledge or skills, the third, behavior or generalizing lessons learned to actual practice, and the fourth, results that would be patient outcomes.72 The authors note that as one moves up this hierarchy, learning is more difficult to measure. A survey can measure hierarchy level 1, a written test, and level 2. Behavior is more difficult but still able to be measured. The authors measured critical thinking in physicians, taking their Quality Improvement course by measuring critical reflection by a survey. The authors constructed a reflection survey, which asked course participants about items constructed to assess their level of reflection on the cases. Least reflective levels consisted of habitual action, and most critically, reflective items asked physicians if they would change the way they do things based on the cases. The results of their intervention showed that physicians had the lowest scores in reaching the higher levels of reflective thinking. However, the reflection scores were shown to be associated with physicians’ perceptions of case relevance (P = 0.01) and event generalizability (P = 0.001). This study was the first to evaluate physician's reflections after a CBL module on adverse events. The assumption is that deeper learning will be more likely to lead to behavioral changes.

Another attempt to measure deeper learning was reported from a dental school in Turkey.8 The authors compared a CBL course with an older LBL course from the previous year by using “SOLO” taxonomy, developed by Biggs and Collis.73 SOLO taxonomy rates the learning outcomes from prestructural through extended abstract. For example, in unistructural, the second item of SOLO, items could be “define”, “identify”, or “do a simple procedure”, whereas in the “extended abstract” level, the items are “evaluate”, “predict”, “generalize”, “create”, “reflect”, or “hypothesize” in higher mental order tasks.8 A post-test was used to measure the responses on the test. The test questions were assigned to SOLO categories. In the first three categories of SOLO taxonomy questions, there was no statistical difference in scores between LBL and CBL groups. In the last two or higher categories of questions based on SOLO taxonomy, there was a statistically significant increase in the scores for relational and extended types of questions for the CBL group (P = 0.014 and 0.026, respectively). This review shows a benefit in higher level learning using a CBL program. Again, the assumption is that by inducing higher order mental tasks, deeper learning will occur and behavioral change will follow.

Two other studies discussed the levels of thinking and preparation for practice. One study compared students in interdisciplinary (ID) versus single-discipline students (SD; clinical anatomy) in a Graduate School for Health Sciences in Missouri, U.S. The two groups had slightly different cases. The ID group had complex ID cases and answered multiple choice questions about the cases. The SD group had cases in their discipline and answered multiple choice cases around the case. The assessment tool was the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal. The mean scores of both groups were not statistically different. However, ID students who scored below the median on the pretest scored significantly higher on the posttest. While this study set out to compare the differences in SD vs ID teaching using CBL, it also compared the effects of an ID course on critical thinking and it appears to be synergistic with improving scores for students who started below the median on testing. This is important in education programs, because while mean scores may not rise, if less students are scoring lower, then less students will fail the course and have to repeat.

The second paper that attempted to measure higher learning outcomes queried dental school graduates who had completed a CBL course during their dental school training.22 The survey was designed to assess the CBL curriculum with respect to actual job requirements of practicing dentists. The graduates spanned 16 years, from 1990 to 2006, and the survey was conducted in 2007–2008. The response rate was 41%. The findings were that the CBL course was associated with positive correlations in “research competence”, “interdisciplinary thinking”, “practical dental skills”, “team work”, and “independent learning/working”. Other items including “problem-solving skills”, “psycho-social competence”, and “business competence” were not scored as highly with respondents. This article measured self-reported competencies and not the competencies as assessed by independent observers. However, it does attempt to link CBL with the actual practice with which it was attempting to teach, which is one of the generally accepted benefits of CBL.

In summary, CBL is defined as an inquiry structured learning experience utilizing live or simulated patient cases to solve, or examine a clinical problem, with the guidance of a teacher and stated learning objectives. Advantages of using CBL include more focusing on learning objectives compared with PBL, flexibility on the use of the case, and ability to induce a deeper level of learning by inducing more critical thinking skills.

Uses of CBL with respect to various fields and various levels in health-care training

CBL is used to impart knowledge in various fields in health care and various fields of medicine. The findings in this review showed that articles demonstrated the use of CBL in medicine,2,4–7,9,10,12–14,18–21,24–26,30,33,34,36,37,39–44,46,48–62,64–67 dentistry,8,15,16,22,23,28 pharmacology,11,27,29,35,45,63 occupational and physical therapy,31 nursing,5,21,38,47,51 allied health fields,32 and child development.17

Eighteen fields of medicine were seen in this review, from internal medicine and surgery to palliative medicine and critical care (Fig. 2, “fields of study”). Several articles highlight ID care or interprofessional care. A 2011 article in critical care medicine demonstrated the utility of both simulators and CBL on behaviors in critical situations of critical care teams of physicians and nurses.5 Palliative care21 and primary care51,59 articles also reported on using a CBL course for learning with physicians and nurses. An article from the United Arab Emirates discussed how CBL better prepared participants for critical situations as well as basic primary care.59

CBL is also used in various levels, including undergraduate education in the professions, graduate education, and postgraduate education. One field that uses CBL for all levels is surgery. Several articles describe surgical undergraduate medical education. One article describes using a paper and pencil plus live review sessions on improving student knowledge as tested by a standardized test in surgery.6 Another paper from Germany describes initiation of a CBL curriculum for medical students and lists the pitfalls in establishing this curriculum.26 A third undergraduate paper in a medical school course in surgery describes utilizing CBL and a more structured curriculum to aid in knowledge gains. A study utilizing both surgical simulators for laparoscopic procedural skills and CBL for clinical knowledge and reasoning demonstrates learning enhancement using CBL in surgical residents, or graduate surgical training.20 In this study, scores in both procedural ratings during surgery for residents and also knowledge scores when presented with complications from surgery both rated higher in the CBL-enhanced course. Graduate use of CBL in surgery is frequent. CME courses are taught in trauma, which features lectures, skill stations, and simulation-based CBL.74 Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) certification is required for all surgeons who practice in a designated trauma center in the United States.74 In addition, the American College of Surgeons publishes a self-assessment course entitled “SESAP” or Surgical Education and Self-Assessment Program, which is a web or CD-ROM course that is largely case based, with commentaries.75 These two courses are widely available and are constantly revised to reflect new advances in patient care research. The use of CBL programs was employed in undergraduate and graduate including postgraduate fields in this review.

Use of CBL in rural and underserved areas

One practical use of CBL is to use CBL to enhance knowledge in rural or underserved areas. An excellent example of CBL is the Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) program in Arizona and Utah states, United States.10,12 This program was based on the Project ECHO program initially devised at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in 2003.10 In Arizona and Utah, the CDC helped fund a program to teach primary care providers and also provide access to specialist to treat hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients. The primary aim was to increase treatment, as new drugs have become available, which are highly effective in treating HCV. The program works by recruiting primary care physician to participate. An initial teaching session is held on site at the health-care clinic in the rural or underserved area. Then, the provider teams are asked to participate in “tele ECHO” clinics in which participants present cases and have experts in HCV treatment comment. There are also educational sessions. Ninety providers participated, with 66% or 73% being primary care providers in rural or community health centers and not at universities. Over one and a half years, 280 patients were enrolled with 46.1% starting treatment. Other patients were likely not able to be treated, as their laboratory values indicated advanced liver disease. The percentage starting treatment was more than twice as many as expected to receive treatment prior to the project, based on historical controls. In addition to showing how CBL can impact rural medical care, this study is an example of learning assessment measured in patient outcomes.

A second CBL project was used in the United Arab Emirates to train rural practitioner's vital aspects of primary and emergency care using a CBL project.60 The learners were able to provide feedback to the teachers as to the topics needed. This demonstrates the potential for interaction between teachers and learners using CBL, as it is a practical way to teach active practitioners. A third demonstration of using CBL in rural areas is in a report on teaching laboratory medicine in Africa.7 In Sub-Saharan Africa, there is low trust in laboratory medicine services due in part to lower the quality of laboratories. This problem directly impacts patient care. Multiple international agencies are assisting the clinical laboratories in Sub-Saharan Africa in order to improve the quality of service. According to this report, the quality problem has led to decreased trust in laboratory medicine in the region. The course, given at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia, was initiated to provide knowledge and also increase trust in laboratory medicine. The participants were 21 residents (graduate medical education), 3 faculty members, and 4 laboratory workers. The course was structured with both lectures and cases. Students were given homework for the differing cases. The assessments were both knowledge gains and also surveys of satisfaction for the course. Ratings on the survey were by ratings on a Likert scale of 1 (least valuable) to 5 (most valuable). Regarding the methods of delivery, the CBL sessions were rated highest with 85% of learners rating them as most valuable. In all, 81% rated case discussions as most valuable. Lectures received the most valuable rating by 65%. On the 12 question pre-/posttest, the mean score rose and also the number of questions answered correctly by the majority of learners.7 These reports from three continents demonstrate that CBL is a practical way to impart knowledge in a diverse range of topics to clinicians who may be remote from a medical university.

Delivery of CBL: implementation and media

As illustrated in the above examples of use of CBL in rural settings, CBL use is varied as to the delivery method and implementation. Several articles demonstrate the importance of preparation for use in CBL. As many practitioners and students in all fields likely have more experience with LBL, participating in a course with CBL requires a different strategy and mindset in order to reach learning objectives. Preparation of both students and teachers in a CBL format is also very important for success. Two studies highlight the preparation and implementation of CBL: one not as successful as the other. In a qualitative study of introducing a new CBL format series to undergraduate medical students based in Sweden, the authors found that preparation of both students and faculty was likely inadequate for complete success. This study, held at the Karolinska Institutet, described the implementation of a CBL format for learning surgery during a semester course. All LBL classes were replaced with CBL sessions. The authors noted that at this time, there were organizational obstacles to starting a CBL course: lack of time and funds for faculty training. As such, faculty training was delayed and decreased. The study was a survey of five students and five faculty, who were picked from larger pools. There was a lot of criticism by students that the CBL needed more structure, or that the faculty often turned the CBL session more into a lecture session. The faculty described problems with getting the students to engage, and also with the lack of preparation for teaching in that format. Still, the overall impression was that CBL could increase interactive learning for this level of student.26 This study demonstrates how lack of adequate preparation can impact a CBL experience for both faculty and students.

Another article demonstrated the differences in student motivation for autonomous learning, which was different, depending on how CBL was introduced. In a study of child development students in Sweden, there were four group methods to compare how students learned, depending on how CBL was introduced. The four groups were as follows: (1) LLL or all lecture, (2) CCCC or all CBL, (3) LCLC in which lecture and CBL were alternated in each session after the introduction, and (4) LLCC, in which there were three sessions with all lectures, two mixed lecture plus CBL, and two CBL only lectures to finish. There was a knowledge pretest and post-test to assess what the authors call prior knowledge (pretest) and achievement (posttest). Student motivation for learning was assessed by means of a modified Academic Self-Regulation Scale.76 The results were that achievement scores and also autonomous motivation were both the highest in the LLCC group, or the group in which CBL was introduced after LBL. The authors conclude that students are more prepared for CBL after some foundational knowledge is imparted. These two articles demonstrate that both teacher and student preparation is necessary for a successful CBL learning encounter.

Use of CBL to impact patients and measurement of results

As described earlier, the Kirkland model of learning and assessment of outcomes includes assessment of the results of the training as its final method of assessing an intervention. In other words, how did the training impact patient care or its surrogate marker? Four recent studies illustrated how CBL can impact patient care.10,12,40,54,69 The first, already described, is the Project ECHO for HCV treatment, which resulted in 46.1% of patients in the areas affected being started on treatment, and a large proportion of those treated being started on the newer antivirals. The second study was a study on practices by primary care physicians on treating diabetic patients. In this study, 122 primary care physicians (Family and Internal Medicine) at 18 sites were divided into three groups to enhance diabetes care. Group A received surveys and no intervention and served as a control group; group B received Internet-based software with three cases in a virtual patient encounter. The cases had simulated time and could include laboratory and medication orders and follow-up visits. After the cases, the physicians received feedback in the form of what an expert would do. Group C received the same CBL as group B with the addition of 60 minutes of verbal feedback and instruction from a physician opinion leader. The authors were able to obtain clinical data for the results. The results were that group B had a significant decline in hemoglobin A1C measures, the most common means of assessing glucose control over time in diabetics, while groups A and C did not. Groups B and C had a significant decline in prescribing metformin in patients with contraindications also. This demonstrates favorable clinical results using a CBL intervention.40 The third was a study to institute chlamydia screening in offices. While the intervention did not globally increase chlamydia screening, the impact was that there was less of a decay on chlamydia screening in the intervention groups.54 The last study demonstrated a CBL study in Portugal, which demonstrated an increase in reporting of adverse drug events after a CBL intervention in a study population of over 4000 physicians.69 These four articles describe the use of CBL to impart medical knowledge and the use of patient outcomes to assess that learned knowledge. This is the ultimate test of learning for health-care practitioners: knowledge that improves patient care.

Limitations of this Review

This review was an attempt to classify a term, case-based learning, which is used frequently. In reviewing articles, this term was used as a search term. It is possible that articles written which would fit the definition of CBL but were termed differently by the individuals writing that article might have been missed. In addition, foreign language articles were not retrieved if there was not an English translation. There may be additional articles that would be instructional in other languages. The higher number of articles retrieved from North America may be biased by using a United States database. In an attempt to describe the various articles, which were termed case-based learning, the methods of delivery and evaluation were described in terms familiar to medical personnel. In the learning situation, these terms might be describing slightly different experiences. For example, several articles described the use of an observed skills examination to evaluate the learner; this examination was classified as “observed skills clinical examination or OSCE”. These OSCEs might have been more, or less, stringent. In defense of the search strategy, since the objective of the article was to write about what is currently considered case-based learning, this item was used as the search term. In order to classify and further define what exactly is CBL and how it is used, putting into discrete categories the described methods of delivery and evaluation was necessary, or else the review would reduce to a listing of separate articles without being able to provide a meaningful commentary.

Conclusions

CBL is a tool that involves matching clinical cases in health care-related fields to a body of knowledge in that field, in order to improve clinical performance, attitudes, or teamwork. This type of learning has been shown to enhance clinical knowledge, improve teamwork, improve clinical skills, improve practice behavior, and improve patient outcomes. CBL advantages include providing relevance to the adult learner, allowing the teacher more input into the direction of learning, and inducing learning on a deeper level. Learners or students in health care-related fields will one day need to interact with patients, and so education that relates to patient is particularly relevant. Relevance is an important concept in adult education. CBL was found to be used in all continents. Even limiting the search to English and English translations, articles were found on all continuously inhabited continents. This finding demonstrates that the use of CBL is not isolated to Western countries, but is used worldwide. In addition, based on the number and variety of fields of medicine and health care reported, CBL is used across multiple fields.

In reviewing the worldwide use of CBL, several constants became apparent. One is that this involves a case as a stimulant for learning. The second is that advance preparation of the learner is necessary. The third is that a set of learning objectives must be adhered to. A comparison with PBL across several articles revealed that most teachers who use CBL, in contrast to PBL, need to get through a list of learning objectives, and in so doing, must provide enhanced guidance to the learning session. That adherence to learning objectives was evident in most articles. There were varied methods of delivery, depending on the learning situation. That is one of the practical aspects of learning sessions termed case-based learning or CBL. The teachers used cases within their realm of teaching and adapted a CBL approach to their situation; for example, live CBL might be used with medical students, video cases might be used with practitioners. CBL differs from PBL in that it can cover a larger amount of topics because of the stated learning objectives, and guidance from the teacher or facilitator who does not allow unguided tangents, which may delay covering the stated objectives. Contrasting CBL with CBL, in PBL, the focus is on the process of learning as much as the topic, whereas in CBL, the learning objectives are stated at the outset, and both learners and teachers try to adhere to these. Because there are stated objectives at the outset of the learning experience in CBL, these objectives can be tested to see if they are met. These tests of knowledge were explored as methods of evaluation, which varied.

The methods of evaluation ran the range of Kirkpatrick's hierarchy of learning. One of the important aspects of CBL which was explored was that perhaps CBL could induce learning on a deeper level. And so going up the hierarchy of learning, some evaluations were simple surveys of the learners/and or the teachers on how they liked the CBL intervention. Some were tests of knowledge or skills learned. A few studies evaluated practice behavior; that is, going beyond knowledge learned into what behaviors that knowledge induced. The last hierarchy was how the knowledge learned from CBL affected actual patients: a few studies revealed that patient outcomes were affected positively from CBL. Thus, published studies of CBL spanned the hierarchy of learning, from opinions of the activity to actual patients affected by the learning of practitioners.

In summary, CBL was found to be practiced worldwide, by various practitioners, in various fields. CBL delivery was found to be varied to the situation. Methods of evaluation for CBL included all the steps on Kirkpatrick's hierarchy of learning and demonstrated that CBL could be shown conclusively to produce deeper learning.

To repeat the definition included earlier in this review, CBL is a form of learning that involves a clinical case, a problem or question requiring student thought, a set of learning objectives, information given prior and during the learning intervention, and a measured outcome.

CBL imparts relevance to medical and related curricula, is shown to tie theory to practice, and induce deeper learning. CBL is practical and efficient as a mode of teaching for adult learners. CBL is certain to become part of every medical and health profession's curriculum.

Author Contributions

Conceived the concepts: SFM. Analyzed the data: SFM. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: SFM. Made critical revisions: SFM. The author reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer Review:Four peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 779 words, excluding any confidential comments to the Academic Editor.

Competing Interests:Author discloses no external Funding sources.

Funding:SFM has been selected as a local site primary investigator for a study of a new tissue insert for use in surgical repair of ventral hernia. The study is sponsored by BARD-Davol Inc.

Paper subject to independent expert single-blind peer review. All editorial decisions made by independent Academic Editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of Competing Interests and Funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

References

- 1.Knowles M.S., Holton E.F., Swanson R.A. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenstein A., Vaisman L., Johnston-Cox H. et al. Integration of basic science and clinical medicine: the innovative approach of the cadaver biopsy project at the Boston University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2014; 89(1): 50–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thistlewaite J.E., Davies D., Ekeocha S. et al. The effectiveness of case based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review. BEME guide number 23. Med Teach. 2012; 34: E421–E444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinivasan M., Wilkes M., Stevenson F., Nguyen T., Slavin S. Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Acad Med. 2007; 82(1): 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frengley R.W., Weller J.M., Torrie J. et al. The effect of a simulation-based intervention on the performance of established critical care unit team. Crit Care Med. 2011; 39(12): 2605–2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLean S.F., Horn K., Tyroch A.H. Case based review questions, review sessions, and call schedule type enhance knowledge gains in a surgical clerkship. J Surg Educ. 2012; 70: 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guarner J., Amukele T., Mehari M. et al. Building capacity in laboratory medicine in Africa by increasing physician involvement: a laboratory medicine course for clinicians. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015; 143: 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilgüy M., Ilgüy D., Fişekçğlu E., Oktay I. Comparison of case-based and lecture based learning in dental education using the SOLO taxonomy. J Dent Educ. 2014; 78: 1521–1527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braeckman L., Kint L.T., Bekaert M., Cobbaut L., Janssens H. Comparison of two case-based learning conditions with real patients in teaching occupational medicine. Me d Teach. 2014; 36: 340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitruka K., Thornton K., Cusick S. et al. Expanding primary care capacity to treat hepatitis C virus infection through an evidence-based care model— Arizona and Utah 2012–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63(18): 393–398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armor B.L., Bulkely C.F., Truong T., Carter S.M. Assessing Student Pharmacists’ ability to identify drug related problems in patients within a patient centered medical home. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014; 78(1): 1–6. [Article 6]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora S., Thornoton K., Komaromy M., Kalishman S., Katzman J., Duhigg D. Demonopolizing medical knowledge. Acad Med. 2014; 89: 30–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gade S., Chari S. Case-based learning in endocrine physiology: an approach toward self-directed learning and the development of soft skills in medical students. Adv Physiol Educ. 2013; 37: 356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malau-Aduli B.S., Lee A.Y.S., Cooling N., Catchpole M., Jose M., Turner R. Retention of knowledge and perceived relevance of basic sciences in an integrated case-based learning (CBL) curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2013; 13(139): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du G.F., Shang S.H., Xu X.Y., Chen H.Z., Zhou G. Practising case-based learning in oral medicine for dental students in China. Eur J Dent Educ. 2013; 17: 225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadershahi N.A., Bender D., Beck L., Lyon C., Blaseio A. An overview of case-based and problem-based leaning methodologies for dental education. J Dent Educ. 2013; 77(10): 1300–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baeten M., Dochy F., Struyven K. The effects of different learning environments on students’ motivation for learning and their achievement. Br J Educ Psychol. 2013; 83: 484–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.William J.H., Huang G.C. How we make nephrology easier to learn: computer-based modules at the point-of-care. Med Teach. 2014; 36: 13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Distlehorst L.H., Dawson E., Robbs R.S., Barrows H.S. Problem-based learning outcomes: the glass half-full. Acad Med. 2005; 80(3): 294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palter V.N., Orzech N., Reznick R.K., Grantcharov T.P. Validation of a structured training and assessment curriculum for technical skill acquisition in minimally invasive surgery. Ann Surg. 2013; 257(2): 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellman M.S., Schulman-Green D., Blatt L. et al. Using online learning and interactive simulation to teach spiritual and cultural aspects of palliative care to interprofessional students. J Palliat Med. 2012; 15(11): 1240–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keeve P.L., Gerhards U., Arnold W.A., Zimmer S., Zöllner A. Job requirements compared to dental school education: impact of a case-based learning curriculum. GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung. 2012; 29(4): 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woelber J.P., Hilbert T.S., Ratka-Krüger P. Can easy-to-use software deliver effective e-learning in dental education? A randomized controlled study. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012; 16: 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogoch I.I., Frost D.W., Bridge S. et al. Morning report blog: a web-based tool to enhance case-based learning. Teach Learn Med. 2012; 24(3): 238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karpa K. Development and implementation of an herbal and natural product elective in undergraduate medical education. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012; 12(57): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nordquist J., Sundberg K., Johansson L., Sandelin K., Nordenstrom J. Case-based learning in surgery: lessons learned. World J Surg. 2012; 36: 945–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persky A.M. The impact of team-based learning on a foundational pharmacokinetics course. Am J Pharm Edu. 2012; 76(2): 1–10. [Article 31]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alcota M., Muñoz A., González F.E. Diverse and participative learning methodologies: a remedial teaching intervention for low marks dental students in Chile. J Dent Educ. 2011; 75(10): 1390–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begley K.J., Coover K.L., Tilleman J.A., Haddad A.M.R., Augustine S.C. Medication therapy management training using case studies and the MirixaPro platform. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011; 75(3): 1–6. [Article 49]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kourdioukova E.V., Verstraete K.L., Valcke M. The quality and impact of computer supported collaborative learning (CSCL) in radiology case-based learning. Eur J Radiol. 2011; 78: 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parmar S.K., Rathinam B.A.D. Introduction of vertical integration and case-based learning in anatomy for undergraduate physical therapy and occupational therapy students. Anat Sci Educ. 2011; 4: 170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman S.C., Short G.F.L., Hendrix E.M., Timson B.F. Impact of interdisciplinary learning on critical thinking using case study method in allied health care graduate students. J Allied Health. 2011; 40(1): 15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittich C.M., Lopez-Jimenez F., Decker L.K. et al. Measuring faculty reflection on adverse patient events: development and initial validation of a case-based learning system. J Gen Intern Med. 2010; 26(3): 293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Layne K., Nabeebaccus A., Fok H., Lams B., Thomas S., Kinirons M. Modernising morning report: innovation in teaching and learning. Clin Teach. 2010; 7: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall L.L., Nykamp D. Active-learning assignments to integrate basic science and clinical course material. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010; 74(7): 1–5. [Article 119]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciraj A.M., Vinod P., Ramnarayan K. Enhancing active learning in microbiology through case based learning: experiences from an Indian medical school. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010; 53(4): 729–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Telner D., Bujas-Bobanovic M., Chan D. et al. Game-based versus traditional case-based learning: comparing effectiveness in stroke continuing medical education. Can Fam Physician. 2010; 56: e345–e351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith M., Johnson K.M., Seydel L.L., Buckwalter K.C. Depression training for nurses. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010; 3(3): 162–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dietrich J.E., De Silva N.K., Young A.E. Reliability study for pediatric and adolescent gynecology case-based learning in resident education. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010; 23: 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Connor P.J., Speri-Hillen J.M., Johnson P.E. et al. Simulated physician learning intervention to improve safety and quality of diabetes care: a randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2009; 32(4): 585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan K., Leonard M., Guerin S., Donnelly S., Conroy M., Meagher D. Validation of the confusion assessment method in the palliative care setting. Palliat Med. 2009; 23: 40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulier R., Hadley J., Weinbrenner S. et al. Harmonising evidence-based medicine teaching: a study of the outcome of e-learning in five European countries. BMC Med Educ. 2008; 8(27): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghosh S., Pandya H.V. Implementation of integrated learning program in neurosciences during first year of traditional medical course: perception of students and faculty. BMC Med Educ. 2008; 8: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eversmann-Kühne L., Eversmann T., Fischer M.R. Team- and case-based learning to activate participants and enhance knowledge: an evaluation of seminars in Germany. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008; 28(3): 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dupuis R.E., Persky A.M. Use of case-based learning in a clinical pharmacokinetics course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008; 72(2): 1–7. [Article 29]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Webb T.P., Duthie E. Geriatrics for surgeons: infusing life into an aging subject. J Surg Educ. 2008; 65(2): 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giddens J.F. The Neighborhood: a web-based platform to support conceptual teaching and learning. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2007; 28(5): 251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landry M.D., Markert R.J., Kahn M.J., Lazarus C.J., Krane N.K. A new approach to bridging content gaps in the clinical curriculum. Med Teach. 2007; 29: e347–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwartz L.R., Fernandez R., Kouyoumjian S.R., Jones K.A., Compton S. A randomized comparison trial of case-based learning versus human patient simulation in medical student education. Acad Emerg Med. 2007; 14: 130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quillen D.A., Cantore W.A. Impact of a 1-day ophthalmology experience on medical students. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113: 2307–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pearson D., Pandya H. Shared learning in primary care: participant's views of the benefits of this approach. J Interprof Care. 2006; 20(3): 302–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lai C.J., Aagaard E., Brandenburg S., Nadkarni M., Wei H.G., Baron R. Brief report: multiprogram evaluation of reading habits of primary care internal medicine residents on ambulatory rotations. J Gen Intern Med. 2006; 21: 486–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allilson J.J., Kiefe C.I., Wall T. et al. Multicomponent internet continuing medical education to promote chlamydia screening. Am J Prev Med. 2005; 28(3): 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hansen W.F., Ferguson K.J., Sipe C.S., Sorosky J. Attitudes of faculty and students toward case-based learning in the third-year obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 192: 644–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shokar G.J., Bulik R.J., Baldwin C.D. Student perspectives on the integration of interactive web-based cases into a family medicine clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2010; 17(1): 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waydhas C., Taeger G., Zettl R., Oberbeck R., Nast-Kolb D. Improved student preparation from implementing active learning sessions and a standardized curriculum in the surgical examination course. Med Teach. 2004; 26(7): 621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massonetto J.C., Marcellini C., Assis P.S.R., de Toledo S.F. Student responses to the introduction of case-based learning and practical activities into a theoretical obstetrics and gynecology teaching programme. BMC Med Educ. 2004; 4(26): 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nackman G.B., Bermann M., Hammond J. Effective use of human simulators in surgical education. J Surg Res. 2003; 115: 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Revel T., Yussuf H. Taking primary care continuing professional education to rural areas: lessons from the United Arab Emirates. Aust J Rural Health. 2003; 11: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chew F. Distributed radiology clerkship for the core clinical year of medical school. Acad Med. 2002; 77(1): 1162–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cook D.A., Thompson W.A., Thomas K.G., Thomas M.R., Pankratz V.S. Impact of self-assessment questions and learning styles in web-based learning: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. Acad Med. 2006; 81(3): 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nackman G.B., Sutyak J., Lowery S.F., Rettie C. Predictors of educational outcome: factors impacting performance on a standardized clinical evaluation. J Surg Res. 2002; 106: 314–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li S., Yu B., Yue J. Case-oriented self-learning and review in pharmacology teaching. Am J Med Sci. 2014; 348(1): 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balzora S., Wolff M., Wallace T. et al. Assessing the utility of a pocket sized inflammatory bowel disease educational resource designed for gastroenterology fellows. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19: S60. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herdeiro M.T., Ribeiro-Vaz I., Ferreira M., Polonia J., Falcao A., Figueiras A. Workshop-and Telephone-Based interventions to improve adverse drug reaction reporting. A cluster—randomized trial in Portugal. Drug Safety. 2012; 35(8): 655–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lam A.K.Y., Veitch J., Hays R. Resuscitating the teaching of anatomical pathology in undergraduate medical education: web-based innovative clinicopathological cases. Pathology. 2005; 37(5): 360–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rigby H., Schofield S., Mann K., Benstead T. Education research: an exploration of case-based learning in neuroscience grand rounds using the Delphi technique. Neurology. 2012; 79: e19–e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sturdy S. Scientific method for medical practitioners: the case method of teaching pathology in early twentieth-century Edinburgh. Bull Hist Med. 2007; 81(760): 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams B. Case-based learning: a review of the literature—is there scope for this educational paradigm in prehospital education? Emerg Med. 2005; 22: 577–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Donner R.S., Bickley H. Problem-based learning in American medical education: an overview. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1993; 81(3): 294–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berkson L. Problem-based learning: have the expectations been met? Acad Med. 1993; 68(10): 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kirkpatrick D. Great ideas revisited: revisiting Kirkpatrick's Four-Level Model. Train Dev. 1996; 50(1): 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Biggs J.B., Collis K.F. Evaluating the Quality of Learning: the SOLO Taxonomy (Structure of Observed Learning Outcome). New York, NY: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 74.The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; Rotondo, MF, Peterson N. Advance Trauma Life Support Student Manual. 9th ed., American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 75.American College of Surgeons. Surgical Education and Self Assessment Program 15, American College of Surgeons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vansteenkistes M., Sierrens E., Soenens B., Luyckx K., Lens W. Motivational profiles from a self-determination perspective: the quality of motivation matters. J Educ Psychol. 2009; 101(3): 671–688. [Google Scholar]