Abstract

The introduction of a new domain of learning for Personal and Professional Skills in the medical program at the University of Auckland in New Zealand has involved the compilation of a portfolio for assessment. This departure from the traditional assessment methods predominantly used in the past has been challenging to design, introduce, and maintain as a relevant and authentic assessment method. We present the portfolio format along with the process for its introduction and appraise the challenges, strengths, and limitations of the approach within the context of the current literature. We then outline a cyclical model of evaluation used to monitor and fine-tune the portfolio tasks and implementation process, in response to student and assessor feedback. The portfolios have illustrated the level of insight, maturity, and synthesis of personal and professional qualities that students are capable of achieving. The Auckland medical program strives to foster these qualities in its students, and the portfolio provides an opportunity for students to demonstrate their reflective abilities. Moreover, the creation of a Personal and Professional Skills domain with the portfolio as its key assessment emphasizes the importance of reflective practice and personal and professional development and gives a clear message that these are fundamental longitudinal elements of the program.

Keywords: assessment, portfolio, reflection, professionalism

Introduction

Professionalism has been identified as a core domain in medical education, with the Medical Council of New Zealand (MCNZ),1 for example, stating that “Patients are entitled to good doctors. Good doctors make the care of their patients their first concern: they are competent, keep their knowledge and skills up to date, establish and maintain good relationships with patients and colleagues, are honest and trustworthy, and act ethically” (p. 6). The importance of professionalism has been emphasized in the New Zealand Curriculum Framework for Prevocational Medical Training recently adopted by the MCNZ. This document outlines the learning outcomes that are to be substantively completed by the end of the second postgraduate year in practice.

Professionalism has been used as a central concept in creating a new domain of learning in the medical program at the University of Auckland called the Personal and Professional Skills (PPS) domain. This domain runs longitudinally over the five years of the program (Years 2–6; Year 1 comprises a common Health Science selection year). The principal means of assessment for this domain is through the compilation of a portfolio in each year that reflects the learning outcomes for the five themes of the domain. The domain and the portfolio were introduced to Years 2 and 4 of the program in 2013, Years 3 and 5 in 2014, and Year 6 in 2015.

The five themes of learning included in the PPS domain are Professionalism and Reflective Practice, Ethics and the Law, Cultural Competence, Health and Well-being, and Learning and Teaching. These themes were consolidated in 2014 through a systematic review of medical literature on topics included in the PPS domain of learning. The analysis confirmed the importance of inclusion of these themes and also highlighted any significant gaps in medical curricula internationally.

Assessment in this domain of learning can be challenging, as it requires a judgment being made on affective and qualitative elements, such as attitudes, professionalism, the ability for critical reflection, personal growth and development, and how these translate into clinical practice. These are not easily assessed by traditional assessment methods used to measure more objective and standardized medical knowledge.2–6 However, a systematic review of medical education literature on the use of portfolios found that portfolios can support both learning and assessment of these elements in undergraduate medical programs.7

The assessment principles adopted for the PPS domain include the need for more than one overall method of assessment, along with multiple, small samples of evidence over time to provide reliability and allow the assessment of progress. While the assessment for the domain consists of three primary elements to meet the first of these requirements (direct observation by clinical staff, assignments, and portfolio), the assessment event that carries the majority weighting is the portfolio (refer to the grading rubric for Year 4 shown in Table 1). If students fail the portfolio, they are given one opportunity for remediation/resubmission before failing the year. The portfolio is student centered and driven, enables student learning through assessment,2 and allows the compilation and presentation of multiple pieces of evidence to demonstrate how the domain learning outcomes have been achieved. Martin-Kneip (cited by Friedman Ben David et al2) highlights that the “… collection represents a personal investment on the part of the student–-an investment that is evident through the student's participation in the selection of the contents, the criteria for selection, the criteria for judging the merit of the collection and the student's self-reflection” (p. 536). While the use of portfolios in a postgraduate medical context is reasonably well established,2,3,7–10 use in undergraduate medical programs is a more recent phenomenon, with their value becoming increasingly recognized.2,4,7,11–14 In particular, they are valued for their ability to promote reflection.2–4,7,11–15 There are useful discussions and guides available in the literature that identify both strengths and limitations in their use.2–4,7,12,14–17 This includes reference to the difficulty of assessing the work presented, including self-assessment and the ability to reflect critically.3,16 The portfolio assessment process needs to accept the subjective, process-based, and progressive nature of the work being presented, which has driven the development of an assessment matrix at the University of Auckland that focuses on process rather than specific content. This is a qualitative approach that requires the assessor to make a professional judgment.12 Friedman Ben David et al note that the ability to reflect is increasingly being recognized as an important component of medical professionalism2 on the grounds that it requires professionals to consider their own actions from the viewpoint of critically assessing what worked, what did not work, and how that action could be improved for the best patient outcome. Kalet et al5 link reflection to experiential learning, commenting that it “translates the experience of clinical practice into learning and is a crucial intellectual task in professional competency” (p. 1066). Others3,13 link reflection to lifelong learning, maintaining that it provides the foundation for best practice with associated links to patient benefit. According to Driessen et al,7 both medical students and doctors are limited in their ability to engage in reflection and self-assessment, which highlights the importance of including opportunities to develop this important ability in medical programs.

Table 1.

Grading rubric for Year 4 PPS domain.

| DIRECT OBSERVN | ASSIGNMENT | PORTFOLIO ASSMT | DECISION |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pass | Distinction | Distinction | Distinction |

| Pass | Distinction | Pass | Pass |

| Pass | Pass | Distinction | Distinction |

| Pass | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Fail | Pass | Pass | Discuss |

| Pass | Fail | Pass | Discuss |

| Pass | Pass | Fail | Discuss |

| Pass | Fail | Fail | Fail |

| Fail | Pass | Fail | Fail |

| Fail | Fail | Pass | Fail |

| Fail | Fail | Fail | Fail |

The format for the portfolio at the University of Auckland has been developed around the five themes of the PPS domain, whereby the students demonstrate how they have met the learning outcomes for each theme. In addition, they are required to include a table of contents (developed from a portfolio plan), a conclusion, and are recommended to include a curriculum vitae, so that it becomes a growing document that can be used in the future. Templates are provided for optional use for recording evidence, for example, for significant learning events and reading logs.

The introduction of portfolios has presented a challenge to the perceptions and learning of some students in what has previously been a fairly traditional medical school curriculum. However, the standard of student work assessed to date in most cases has been outstanding and has shown evidence of personal and professional development that has not been previously evidenced through assessment. This article presents the process for introducing the portfolio, including the challenges, strengths and limitations, evaluation of data to date, and the ways in which student feedback has been addressed.

Method

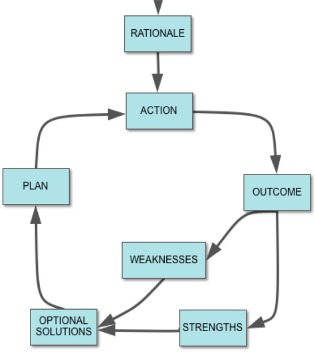

The implementation process employed a cyclical model that was designed to evaluate and improve the use of the portfolio, that could form the basis of the first cycle of action research that will be continued in the future to improve the initiative (Fig. 1). During 2013, the introduction of the portfolio was monitored, and changes were made in 2014. In 2014, feedback from students indicated the need for further modifications, which are currently being implemented, along with the introduction of an electronic platform.

Figure 1.

Portfolio evaluation model.

Student feedback was ascertained from the generic end-of-year course evaluation, which included questions relating to the PPS domain. The number of students in each year varied from 199–260 and there was an average response rate of 50%. In addition, the Auckland University Medical Students Association conducted a student evaluation for the purpose of writing a report for the ongoing medical program accreditation, from which key issues were collated and forwarded to the PPS domain coordinators. The eight portfolio assessors also provided suggestions for improvement at the end of 2013 and 2014. Evaluation feedback, modifications, and qualitative data derived from the portfolios are presented in the Findings section.

Findings

Due to the qualitative nature of the feedback, it was analyzed inductively, through a cross-sectional thematic analysis that sought to ascertain the strongest themes from across the three sources of feedback. The key points presented are listed in Table 2. Qualitative comments directly included in student portfolios have been included in the Discussion section. Given that the PPS coordinators reflexively interpreted the data through their own lens of experience in the portfolio process, which brings with it both strengths and limitations, it is planned to conduct a full, independent evaluation after five years of implementation, at the end of 2017.

Table 2.

Summary of feedback.

| YEAR | FEEDBACK |

|---|---|

| 2013 |

Students

|

|

Assessors

| |

| 2014 |

Students

|

|

Assessors

|

Table 3 indicates the modifications that were made as a direct result of this feedback.

Table 3.

Modifications made.

| YEAR | MODIFICATIONS |

|---|---|

| 2014 |

|

| 2015 |

|

Discussion

It was anticipated that students may have difficulty with personally reflective learning and assessment, as this is a substantial change to previous forms of assessment. However, many students related to the portfolio extremely well, noting that it is the only part of the curriculum in which they can be creative, develop their critical reflection, and show a different aspect of who they are (Table 4). Others appeared to be frustrated by the assessment, perhaps feeling outside of their comfort zone and/or not convinced of the relevance of PPS content or portfolio process, and this resulted in some angry or defensive responses. Anxiety created by a new form of learning or assessment is to be expected.2,17 Even though negative attitudes and misconceptions about reflective learning have been noted in the literature,17 it was disappointing to experience the degree of resistance shown by some. As suggested by Ross et al,17 this may reflect a broader culture in medicine that does not support reflective learning, or understand its importance. There appeared to be a general lack of understanding about the value of the PPS domain and reflective practice. Some students resented being made to think, without reflecting on the importance of why they were being asked to do this.

Table 4.

excerpts from 2014 portfolios.

| I have developed this year. I have seen examples of what I wish to be and examples of what I don't want to be like. I have gained more confidence and this has impacted on my rapport with patient and team. I have begun to understand me and how I fit into this system. I have many areas that need improvement and I will strive to become the best version of me. I know I have not found all the things that need attention or fixing in my career development but this is just the start but I am open to progression so hopefully that is enough for right now. P.S. Really enjoyed this assignment. it has opened my eyes to me. |

| In my portfolio, I have reflected on some situations I have had strong emotional reactions to. This has enabled me to better process my feelings and safely let them go, while respecting the importance of empathy and emotional reactions. I know that listening to my patients will always be the biggest part of my practice, and to me that means being with them in their experience, not just clinically. This portfolio demonstrates a portion of my reflection and learning across different domains as I develop into a competent and well rounded doctor. My reflections have helped me consider where my reactions come from, how to process and use them, and how to improve the care I provide. I know that in the new year, I will be especially looking to work on my biases, cultural competence and further develop my professional skills, as well as whatever experiences fifth year throws at me!! |

| I have not done much active reflection in the past and this was a novel venture for me. What I found difficult was initially setting aside time to sit down and reflect, either in my mind or on paper, as I did not think it was of any benefit. After a couple of entries, however, I found it extremely helpful in the way it allowed me to subjectively reflect on how I felt at the time and objectively reflect on what was good or not so good about something that had happened. This has helped later in the year whenever I found myself in a difficult situation, similar to any I had experienced in the past, as I could then deal with the situation differently, and then reflect and compare how effective I was compared to previous. |

| Reflection has helped me the most with my bedside manner and the way in which I interact with patients. At the start of the year, I felt like I was not prepared to talk to patients. Through 2nd and 3rd years we were always talked to about the doctor-patient relationship and how important it was to maintain professionalism. Although this is true, i have found that it is easy to forget that patients are just people and, as a medical student, I am also just a person. So, although it is important to remain professional, I have found it useful to remember to bring myself back to the principles of treating the patient as a person and not as a cluster of symptoms. |

| “Sometimes, you have to look back in order to understand the things that lie ahead” Yvonne Woon. This quote beautifully summarises what I've learnt from doing my portfolio this year-that looking back and regularly reflecting on clinical and personal experiences helps you to constantly improve yourself, thus making you the best person and doctor you can be. Reflections also helped me to learn how to deal with problems more efficiently, which will be particularly important in the future when I am busier and have more responsibilities … Having an assignment that assessed development in the key areas of personal and professional life, made me confront challenges that I might have otherwise ignored. Having done this regularly throughout the year, I now reflect on all encounters without a second thought because I've enjoyed the benefits this brings. |

Note: Student permission was granted for inclusion of excerpts.

Much of the negative feedback (refer feedback from students, Table 2) came from the more senior students who had been exposed to the program before the implementation of the PPS domain and portfolio. Therefore, we hope this will change over time, particularly with improved orientation sessions highlighting the importance of the PPS domain and the skills required to develop a portfolio for their future careers as doctors. Furthermore, Kalet et al5 discuss that it is reasonable to expect that while some students may not see the relevance of reflective writing early in their training, it may prove useful to them later in their careers. They conclude that while student satisfaction is important, it should not be the only measure used when implementing and evaluating this form of assessment.

Looking critically at the process we have implemented, it appears to meet most of the suggestions for best practice explored in the literature. The strengths of our approach include the following.

Assessment of learning outcomes

The portfolio summatively assesses evidence of attainment of the learning outcomes of the PPS domain longitudinally across the medical program, allowing the assessment of aspects of the program not previously assessed and the assessment of progression.2,6,7,14 Therefore, students must pass the portfolio each year in order to progress to the following year of their program.

Emphasis on adult principles of learning

The portfolio provides authentic assessment of the past and present personal, academic, and clinical experiences that contribute to the themes of the PPS domain.2–5,9,12,15,16 Authentic assessment encourages students to become responsible for their own learning and focus on the development of lifelong learning skills.2,6,9,15 In order to maintain authenticity, it is important to uphold a personal and individualized approach that elicits the real experience of the learner, helps them to consolidate their learning, and make connections between theory and practice.2,3,5,15 According to Kalet et al,5 authentic assessment emphasizes “the process as well as the products of learning“ (p. 1066), which is reflected in our marking rubric. Interestingly, some students doubt the authenticity of entries made by some of their peers, maintaining that they could make them up at the last minute, giving the assessors what they are expecting in order to achieve a good grade. However, on reading the entries, it is fairly apparent across the portfolio whether a student has approached it seriously and consistently over the year. There is also the argument that even the attitude of fake it until you make it is going to teach important reflective skills over time.

Authentic assessment is one of the key principles of adult learning. The use of a portfolio to build on the learning value of student experience through critical reflection emphasizes an adult model of learning. According to Mathers et al,10 this model is more likely to result in deep learning than courses driven by direct teaching input with test/assignment-focused assessment. Challis3 outlines the characteristics that lead to deep learning, from which we can draw additional portfolio characteristics of active rather than passive learning3,10 and the integrated nature of the way knowledge is presented, rather than the more traditional way of seeing knowledge as independent pieces of content.3 Portfolio-based learning is also said to increase self-knowledge and confidence of students.10

Mezirow (cited by Challis3) defines androgeny as “an organised and sustained effort to assist adults to learn in a way that enhances their capability to function as self-directed learners” (p. 372). Central to this is the ability to value, reflect, and learn from experience,16 with experiential and self-directed approaches being said to foster patterns of lifelong learning.3,5,6,13 As outlined by Challis,3 students need to be able to engage in actual experience, critically reflect, conceptualize or make meaning from this experience,18 and then apply the concepts/meaning to new situations. Driessen et al15 “regard reflection as a cyclic process of self-regulation” (p. 1230) and maintain that it is a condition for professional development. To enhance this process, we encourage students to include a concluding section where they can summarize what they have learned personally and professionally over the year and how that translates into their goals for the following year. This also leads into the Year 6 transition to the more goal-focused professional development plan, which is a requirement of the MCNZ for junior doctors.

Summative assessment

The portfolio is suitable for summative assessment,14 based on professional qualities, reflection, and the ability to demonstrate that learning outcomes have been met, rather than purely on content. According to Driessen et al, it needs to be summative if its status is to be maintained in the eyes of students, who tend to be assessment driven,7 and it means that they can be rewarded for their effort in producing a high-quality portfolio. The AMEE Medical Education Guide2 suggests that if it assesses multiple competencies, general standards should be developed rather than being highly specific. Likewise, the systematic review by Driessen et al7 revealed that the use of global criteria with rubrics has a positive impact on interrater agreement, both of which support the process nature of our marking rubric. To assess in an interpretive manner means accepting the subjectivity of the personal and often creative material included,3,4,16 and this is supported by the marking rubric, which has been adapted from the REFLECT rubric.19

While the portfolio has been designed to be a criterion rather than norm referenced,12 the rubric allows for the allocation of a distinction grade for excelling portfolios, which provides a point of discrimination for the overall calculation of distinction for the domain grade for the year. This signals to students the importance of the PPS domain, alongside applied medical knowledge and their clinical attachments. All portfolios with an indication of fail, borderline pass, high pass, or distinction are moderated by the PPS domain coordinators to ensure consistency of standards at grade cut points.

Structure

A portfolio structure that is too standardized is said to decrease authenticity and validity,2 which was one of the drivers for the structure chosen for the PPS portfolio. While we require the students to submit a minimum of two pieces of evidence for each of the five themes of the domain, they are given multiple suggestions in the portfolio guidelines as to what types of evidence they may include. These are not tightly defined–-it is left to the students to select pieces of evidence and reflection that illustrate how they meet the learning outcomes for each of the themes of the domain. It is stressed that their work is assessed on the quality of their reflection rather than the quantity, as we are interested in learning and consequent change in personal assumptions or practice.3 Several authors4,7,13–15 include flexible structure and clear guidelines as requirements for portfolio success, maintaining that too much rigidity carries with it a greater risk of negative reactions from students than too little structure,7 particularly after the initial stage of learning how to reflect.15 In their first year of the medical program (Year 2), students engage in structured small portfolio development tasks to introduce them to the concept of a portfolio and focus on some of the skills that are required, thereby learning the process of reflection.14,17 They are given feedback on these tasks before moving on to the submission of a portfolio at the end of Year 3.

Variety of evidence

The portfolio may include a wide variety of forms of evidence over time and allows the students to be creative and personalize their learning.2,6,7 For example, many students express their reflections in poetry or art, particularly when providing evidence for the Health and Well-being theme. It is not intended that the portfolio is purely a collection of evidence, rather each piece is accompanied by reflection on its relevance to the PPS learning outcomes and how it has led to their personal or professional development.3 That is, they need to articulate what they have learned through the process of critical reflection.8 This engages them actively in the process of self-assessment and also encourages them to synthesize their learning from activities they have been engaged in to demonstrate their personal or professional development over time.9

Finally, this discussion turns to the arguments that arise with regard to validity, reliability, and standardization. Our stance is that a highly structured portfolio diminishes its strength in assessing personal and professional development. However, the trade-off for this is that it means the content of the portfolios cannot be standardized for the traditional objective form of marking that is often valued in medical education. It also means sacrificing high levels of reliability.4 However, we argue that traditional measures of standardization and reliability are not desirable/appropriate when assessing this domain of learning and that either controlling the format or marking in a standardized checklist fashion limits the portfolio as a reflective tool.4 As stated by Pitts et al,16 “as assessment becomes less standardized, distinctions between reliability and validity blur. It may be that traditional psychometric views of reliability and validity are actually limiting more meaningful educational approaches. These difficulties will persist as long as assessment is based on a standardized, reductionist and comparative approach that may measure the irrelevant while attempting to measure the unmeasurable” (p. 354).

As stated previously, we accept the intrinsically personal and subjective nature of the material presented, grading it according to process, not content. A degree of standardization is achieved through the requirement for students to provide evidence of meeting the learning outcomes for each theme of the domain, as reflected in the structure of the portfolio. The personalized nature of the portfolio, however, contributes directly to its authenticity and, therefore, validity.2,7 Challis3 reminds us that the subjectivity always involved in assessing portfolios is not a disadvantage, as our aim is to decide “whether appropriate learning has taken place and has been demonstrated, in accordance with the development needs of the learner” (p. 376).

There are two primary areas that still need to be addressed before a larger scale independent evaluation of the portfolio is conducted. First, it is clear in the literature and from student feedback that it would be valuable to have portfolio mentors who can be available to assist with the process of compiling their portfolios. In 2015, training was introduced for the small group of tutors who are involved in teaching the PPS domain in Years 2 and 3, to enable them to work with their groups of students in a more consistent and informed manner. However, in Years 4–6, we have so far had mixed success. Portfolio drop-in times have been scheduled where students can bring questions or problems to the PPS domain coordinators; however, there has not been a high level of uptake to date. A mentoring scheme is being explored for students wishing to process difficult clinical experiences and has been introduced primarily as a pastoral care initiative. However, portfolio feedback in 2014 indicated that for some students, the process of writing about a challenging clinical experience raised their awareness of their emotions and vulnerability, thus increasing their anxiety. Some students indicated the need to be helped to process these feelings and requested a forum in which to do so. Reflective groups run in the style of Balint groups are held for Year 5 and 6 students and are currently being evaluated as a research project. Ideally, individually assigned clinical mentors would be valuable, but this has not proved to be logistically possible as yet.

Second, in 2015, further training of assessors has been implemented to aid feedback consistency. The latter has also been enhanced by the use of Turnitin for marking, with preloaded feedback comments that can be dragged and dropped onto the portfolio document, along with free text as required. Friedman Ben David et al2 note that “Misclassification into pass/fail or referred categories due to raters’ source of error is a main concern regarding disagreement among raters” (p. 544). The use of a rubric with global criteria,7 a small group of assessors, and moderation of all portfolios close to decision cut points by the PPS coordinators ameliorates this problem, but the latter places a high workload on the coordinators at the end of the academic year. Multifacet Rasch measurement modeling that will take into account interrater differences is planned with one cohort of portfolios at the end of 2015.

Ongoing evaluation will be continued through student feedback. However, we see the need for a larger independent evaluation once the first students introduced to the portfolio have reached the end of their undergraduate training (end of 2017). In addition, it may be interesting to investigate student performance in the PPS domain compared with their performance in other domains with a different form of assessment (eg, Applied Science for Medicine), as suggested by Friedman Ben David et al.2 We anticipate that there is unlikely to be an exact correlation, given that it assesses a different form of knowledge and skills.

Conclusion

The implementation of a portfolio for the assessment of the PPS domain in the medical program at the University of Auckland has proved to be an important part of the redeveloped curriculum. It has highlighted the importance of PPS topics and has provided an opportunity and incentive for students to reflect on aspects of their personal and professional development, with the aim of improving their practice as doctors. In the process, we have learned several aspects about students that previously may have remained unknown, which has led in some cases to conversations with students that will hopefully make a difference to their learning and development trajectories. We have also seen many high-quality and insightful portfolios that demonstrate a synthesis of personal and professional qualities that are inspiring and which we hope are an indication that these students will develop into excellent doctors. With the increasing use of, and requirement for, the compilation of professional portfolios in the medical profession internationally, especially at postgraduate level, there is real benefit for students in becoming familiar with this process of pregraduation.

The portfolio implementation process has also provided challenges, particularly with respect to student perception of the relevance of reflective practice in the real world of being a doctor. We have had to contend with skepticism from some students (along with initial reservations by staff) as they have been challenged to develop what has been, for many, a new way of thinking and representing themselves in an assessment task. In this domain of learning, students cannot cram and dump information they have learned in a way that rewards those with good memories. They are being asked to develop self-assessment and reflective capabilities that call for constant reevaluation and changes to practice, and they are required to take ownership of the completion of a year-long assignment, which requires good time management and motivation. Therefore, we had to respond with care to student feedback in order to make the portfolio process acceptable and safe.

It has also been a learning process for the domain coordinators introducing the assessment. In particular, we learned the value of a cyclic, flexible, and ongoing process of evaluation that has allowed us to continuously reflect on what is working and what needs to change in order to be responsive to student needs and at the same time create a curriculum change that aims to create better doctors. As stated by a Year 5 student, “I really appreciate that the PPS department seems to take real interest in student feedback and changes their methods based on that–-thank you!” We hope that as students come to trust our responsiveness, they will become increasingly open to the importance of taking on the responsibility for their own learning in the PPS domain.

Author Contributions

Analyzed the data: JY and FM. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: JY. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: JY and FM. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: JY and FM. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: JY and FM. Made critical revisions and approved final version: JY and FM. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are coordinators of the Personal and Professional Skills domain, MBChB programme, University of Auckland.

Footnotes

Peer Review:Fourteen peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 3554 words, excluding any confidential comments to the Academic Editor.

Competing Interests:Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding:Authors disclose no external Funding sources.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review. All editorial decisions made by independent Academic Editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of Competing Interests and Funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

References

- 1.St George I. Cole's Medical Practice in New Zealand. 12th ed. Wellington: Medical Council of New Zealand; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman Ben David M., Davis M., Harden R., Howie P., Ker J., Pippard M. AMEE medical education guide No. 24: portfolios as a method of student assessment. Med Teach. 2001; 23(6): 535–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Challis M. AMEE medical education guide No. 11 (revised): portfolio-based learning and assessment in medical education. Med Teach. 1999; 21(4): 370–386. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitts J. Portfolios, personal development and reflective practice. In: Swanwick T., ed. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. 1st ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell; 2010: 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalet A., Sanger J., Chase J. et al. Promoting professionalism through an online professional development portfolio: successes, joys and frustrations. Acad Med. 2007; 82(11): 1065–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Schaik S., Plant J., O'Sullivan P. Promoting self-directed learning through portfolios in undergraduate medical education: the mentors’ perspective. Med Teach. 2013; 35: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driessen E., van Tartwijk J., van der Vleuten C., Wass V. Portfolios in medical education: why do they meet with mixed success? A systematic review. Med Educ. 2007; 41: 1224–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snadden D., Thomas M. The use of portfolio learning in medical education. Med Teach. 1998; 20(3): 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harden R. Trends and the future of postgraduate medical education. Emerg Med J. 2006; 23: 798–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathers N., Challis M., Howe A., Field N. Portfolios in continuing medical education—effective and efficient? Med Educ. 1999; 33: 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon J. Assessing students’ personal and professional development using portfolios and interviews. Med Educ. 2003; 37: 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driessen E., van Tartwijk J., Vermunt J., van der Vleuten C. Use of portfolios in early undergraduate medical training. Med Teach. 2003; 25(1): 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driessen E., van Tarkwijk J., Dornan T. The self critical doctor: helping students become more reflective. Br Med J. 2008; 336: 827–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Sullivan A., Harris P., Hughes C. et al. Linking assessment to undergraduate student capabilities through portfolio examination. Assess Eval High Educ. 2012; 37(3): 379–391. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Driessen E., van Tartwijk J., Overeen K., Vermunt J., van der Vleuten C. Conditions for successful reflective use of portfolios in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2005; 39: 1230–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitts J., Cole C., Thomas P. Enhancing reliability in portfolio assessment: ‘Shaping’ the portfolio. Med Teach. 2001; 23(4): 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross S., Maclachlan A., Cleland J. Students’ attitudes towards the introduction of a personal and professional development portfolio: potential barriers and facilitators. BMC Med Educ. 2009; 9: 69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mezirow J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wald H., Borkan J., Taylor J., Anthony D., Reis S. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 2012; 87(1): 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]