Abstract

Background

Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) commonly turn to dietary modifications to manage their skin condition.

Objectives

To investigate patient-reported outcomes and perceptions regarding the role of diet in AD.

Methods

One hundred and sixty nine AD patients were surveyed in this cross-sectional study. The 61-question survey asked about dietary modifications, perceptions and outcomes.

Results

Eighty seven percent of participants reported a trial of dietary exclusion. The most common were junk foods (68%), dairy (49.7%) and gluten (49%). The best improvement in skin was reported when removing white flour products (37 of 69, 53.6%), gluten (37 of 72, 51.4%) and nightshades (18 of 35, 51.4%). 79.9% of participants reported adding items to their diet. The most common were vegetables (62.2%), fish oil (59.3%) and fruits (57.8%). The best improvement in skin was noted when adding vegetables (40 of 84, 47.6%), organic foods (17 of 43, 39.5%) and fish oil (28 of 80, 35%). Although 93.5% of patients believed it was important that physicians discuss with them the role of diet in managing skin disease, only 32.5% had consulted their dermatologist.

Conclusions

Since dietary modifications are extremely common, the role of diet in AD and potential nutritional benefits and risks need to be properly discussed with patients.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, patient-reported outcomes, diet

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease with prevalence estimated of 10–12% in US children and 7–10% in US adults (1). In the past several decades, the prevalence of AD has increased, suggesting that environmental exposures may be triggering and/or flaring the disease in predisposed individuals (2,3). Diet has been suggested as an important factor in triggering AD besides many other environmental exposures, such as climate, pollution and UV radiation (3).

Much research has been done to better understand the role of diet in AD, however, the literature is controversial and inconclusive. A Cochrane review of nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 421 participants assessed the effects of dietary exclusions for the treatment of established AD and concluded that the evidence available lends little support to the use of exclusion diets in unselected patients (4). However, a recent cross-section study assessed the dietary habits and the prevalence of AD in 17,497 adults and found a significant association between instant noodles, meat and processed food and increased prevalence of AD (5). A 2012 Cochrane review evaluated dietary supplements for treating established AD. They reported that fish oil, vitamin D and vitamin E supplementations have shown symptoms of improvement in several randomized trials, but the evidence was found to be of questionable clinical significant since many of them were small and with poor quality (6). In a recent RCT, however, daily supplementation with 1600 IU of vitamin D significantly improved AD compared to placebo (7).

Studies examining the role of probiotics in AD also demonstrated mixed results; a recent meta-analysis of 25 RCTs suggested that probiotics could be an option for the treatment of AD (8), whereas several studies did not find a correlation between supplementation of probiotics and improvement of the disease (9–11).

Surprisingly, despite the lack of evidence-based recommendations, many patients with AD report eliminating/avoiding particular foods suspected of causing a reaction in a hope that following this dictum might improve their symptoms. In a study by Johnston et al., 75% of patients with AD that were interviewed regarding dietary manipulations reported a trial of dietary change. Only half had those patients consulted a doctor or dietitian before commencing the diet (12,13). Furthermore, the lack of supervision of those dietary changes in AD patients has been associated with risk of nutrient deficiency in both children and adults (14–16).

Presently, only few studies have investigated the relationship between AD and dietary modifications using patient-reported outcomes. To fill this gap, our study surveyed AD patients on how different dietary modifications affected their disease. Objectives of our study include: (1) To investigate the prevalence of specific food exclusions and additions reported by AD patients; (2) To determine where there is consensus among AD patients regarding the influence of certain dietary behaviors on the severity of their skin condition; (3) To understand the attitudes and perceptions of AD patients regarding the role of diet in managing their skin condition.

Materials and methods

Study design and subjects

This is a cross-sectional study that surveyed 169 AD patients between 1 August 2014 and 31 January 2015 to examine the association between diet and AD. The survey was distributed to AD patients online via the National Eczema Association (NEA) and the Eczema Society of Canada (ESC) webpages, newsletters and Facebook pages. Both the NEA and the ESC are nonprofit patient advocacy groups for patients with AD. The NEA and the ESC approvals for use of their online webpage, newsletter and Facebook page were obtained. The study was restricted to participants aged 18 or older.

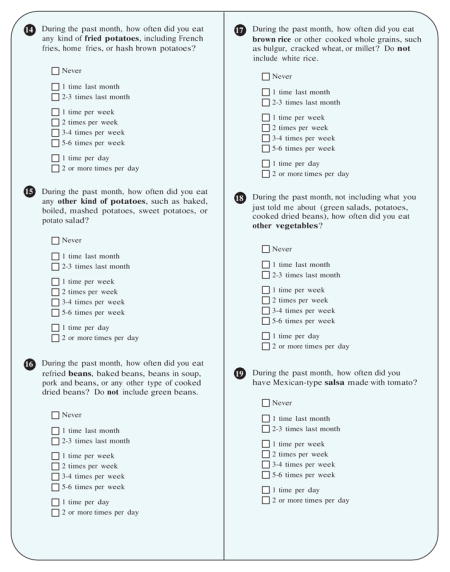

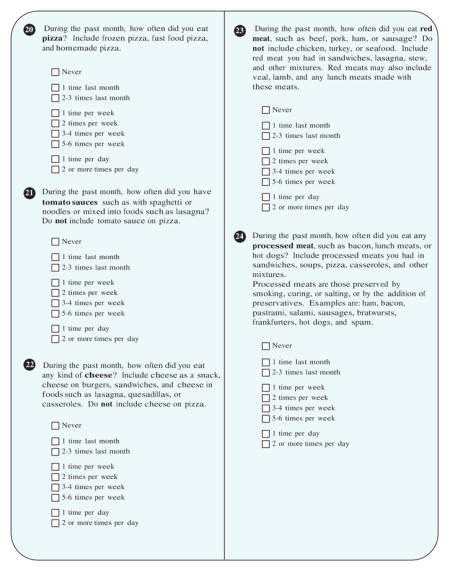

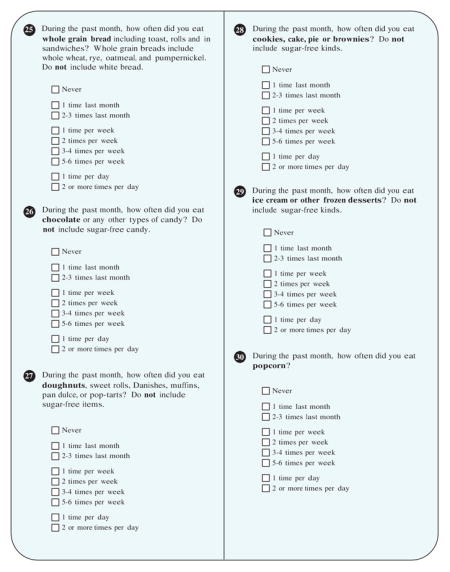

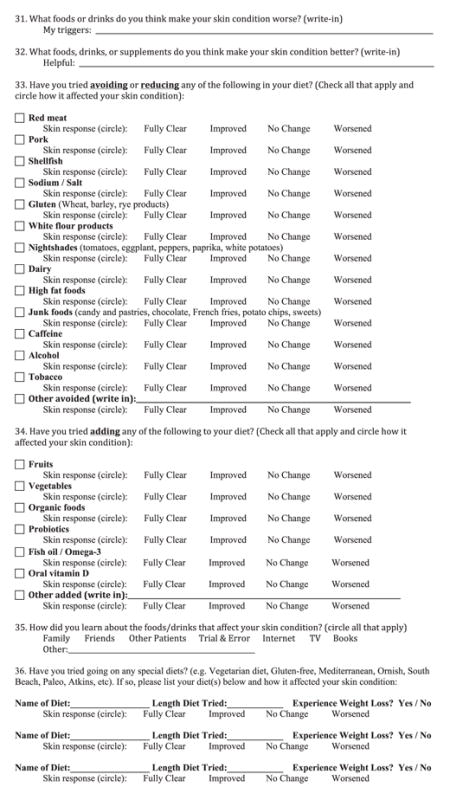

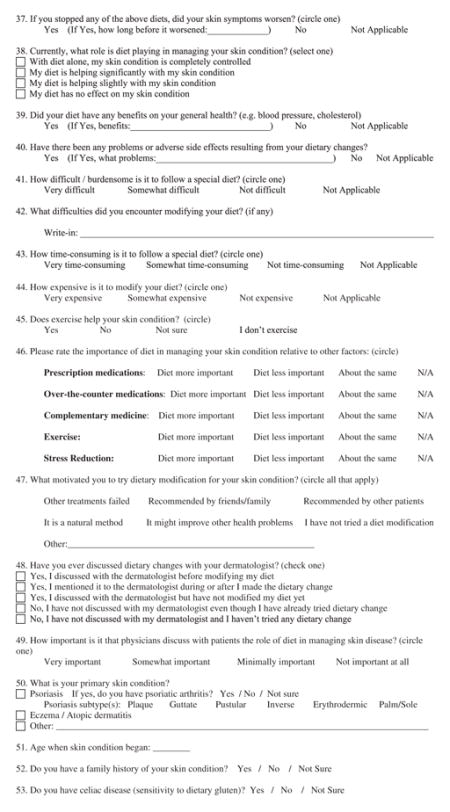

Our survey included 61 questions (Appendix): The questions focused on trials of reduction or addition of different food groups, how skin disease changed with different food groups, patients’ attitudes surrounding diet as a management strategy for their AD, and participant demographics. Questions were developed based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (information for the survey is found at the following link: http://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/evaluation.html), topics of interest found in NEA and ESC discussion forums, popular literature, patient discussion and a review of the scientific literature. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco.

Statistical analysis

Current age and age onset of eczema were calculated as mean and standard deviation. All dietary changes, attitude/perception, and the demographic data were compiled and frequencies reported. Education level was categorized into four groups: less than high school, high school, undergraduate and graduate/professional degree. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kg) divided by square of height (in m) and was categorized into four groups: underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9) and obese (30+). Body surface involvement was categorized into five groups: Barley or very little, <5% body surface, 5–10% body surface, 11–20% body surface and >20% body surface. Severity of eczema was categorized into three groups: mild, moderate and severe. Common dietary items that were specifically reported in the free response portion of the questionnaire to be triggers or to improve skin lesions were compiled and percentiles were reported. In regards to survey inquiries identifying skin responses to the addition or removal of specific dietary items, a positive response is defined as subjects marking fully clear or improved response of their skin lesions, while a negative response is worsening or no change following the specific dietary change. Frequencies of the most consistent dietary changes that had a positive response on skin lesions were reported. Similarly, percentiles of positive responses to free response questions regarding specific diets (such as Atkins, Paleo, gluten free) were compiled.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 169 participants completed the survey. A summary of patient characteristics is shown in Table 1. The mean (SD) age of the sample population was 43.0 (16.7) and 131 respondents (77.5%) were females. Our sample population was predominantly white (124; 74.7%) and the majority had a relatively high education level (133 responders, 80.1%, had either undergraduate or graduate degree). Geographically, most of the responders reside in the US (n =80, 70.2%) and the majority lived in an urban setting (130, 79.3%). Less than 15% of the participants reside in either Canada (n =16, 14%), Europe (n =12, 10.5%), Australia (n =2, 1.7%) or Asia (n =4, 3.5%). The mean (SD) BMI of our sample population was 27.2 (8.2) and 84 patients (49.7%) were either overweight (BMI 25–29.9) or obese (BMI >30).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Variable | Value, N =169 |

|---|---|

| Age, Y | |

| Mean (SD) | 43.0 (16.7) |

| Sex, n % | |

| Male | 38 (22.5) |

| Female | 131 (77.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 124 (74.7) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 21 (12.7) |

| Hispanic | 7 (4.2) |

| Native American | 4 (2.4) |

| African American | 4 (2.4) |

| Other | 16 (9.6) |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | |

| Less than high school | 10 (6.0) |

| High school graduate | 23 (13.9) |

| Undergraduate | 55 (33.1) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 78 (47.0) |

| Area in which the patient lives, n (%) | |

| Urban/suburban | 130 (79.3) |

| Rural | 34 (20.7) |

| Country in which the patient lives, n (%) | N =114 |

| USA | 80 (70.2) |

| Canada | 16 (14.0) |

| Europe | 12 (10.5) |

| Australia | 2 (1.7) |

| Asia | 4 (3.5) |

| Average annual household income, n (%) | |

| <$20,000 | 14 (8.7) |

| $20,000–$40,000 | 17 (10.6) |

| $40,001–$60,000 | 21 (13.0) |

| $60,001–$100,000 | 29 (18.0) |

| >$100,000 | 40 (24.8) |

| Prefer not to say | 40 (24.8) |

| Age onset of Eczema, mean (SD) | 18.2 (20.7) |

| Family history of Eczema, n (%) | |

| Yes | 94 (56.0) |

| No | 52 (31.0) |

| Not sure | 22 (13.1) |

| Severity of Eczema (without treatment), n (%) | |

| Mild | 22 (13.1) |

| Moderate | 66 (39.3) |

| Severe | 80 (47.6) |

| Average BMI, mean (SD) | 27.2 (8.2) |

| Underweight (<18.5), n (%) | 12 (7.1) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9), n (%) | 72 (42.6) |

| Overweight (25–29.9), n (%) | 34 (20.1) |

| Obese 30+, n (%) | 50 (29.6) |

The mean (SD) age onset of eczema was 18.2 (20.7) and family history of eczema was present in the majority of patients (n =94, 56%). The sample population represented all levels of AD severity: 22 (13.1%) with mild disease, 66 (39.3%) with moderate disease and 80 (47.6%) with severe disease. In addition, the body surface area involvement reported by the participants was predominantly less than 10%: 48 patients (28.6%) reported body surface area <5% and 44 patients (26.2%) reported body surface area between 5 and 10%. Thirty-eight patients (22.6%) reported body surface involvement area >20%. In addition, 36 patients (21.3%) reported psoriasis as their secondary skin condition.

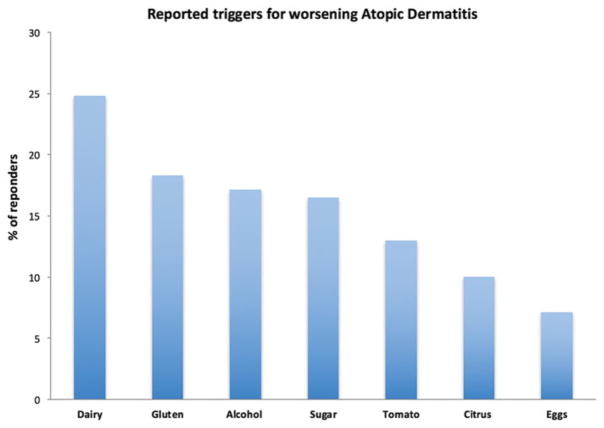

Perceived dietary triggers

Participants were asked to report what foods or drinks made their AD worse. Among survey respondents (n =169), the most common reported triggers were dairy (n =42, 24.8%), gluten (n =31, 18.3%), alcohol (n =29, 17.1%), sugar (n =28, 16.5%), tomatoes (n =22, 13%), citrus (n =17, 10%) and eggs (n =12, 7.1%) (Figure 1). Less commonly reported triggers (2–5% of reported triggers) included meat, soda, spicy foods, processed foods and seafood.

Figure 1.

Reported triggers for worsening atopic dermatitis.

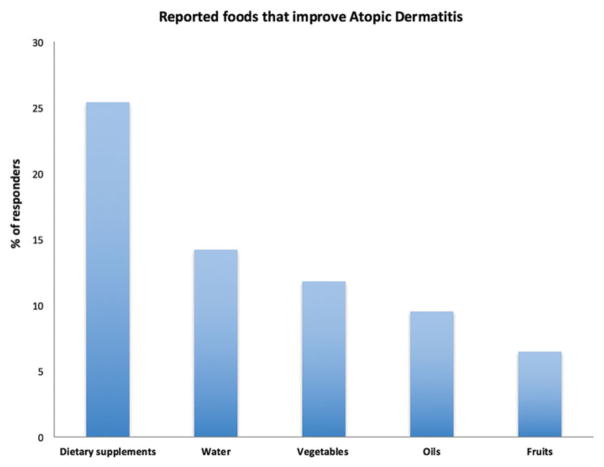

Participants were also asked to report what foods, drinks or supplements made their AD better. The following were reported as foods that may improve their AD when incorporated in patients’ diet: consumption of dietary supplements (probiotics, vitamin D, vitamin C, zinc or omega 3, n =43, 25.4%), water (n =24, 14.2%), vegetables (n =20, 11.8%), oils (primrose oil, hempseed oil, cod liver oil, olive oil or coconut oil) (n =16, 9.5%) and fruits (n =11, 6.5%) (Figure 2). Only three patients (1.7%) reported fish as foods that may improve their AD.

Figure 2.

Reported foods that improve atopic dermatitis.

Dietary modifications

Table 2 presents the food categories that were avoided/reduced or added by participant.

Table 2.

Food categories that were avoided/reduced or added by participant.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Food categories that were avoided/reduced by participants, n (%) | N =147 |

| Junk foodsa | 100 (68.0) |

| Dairy | 73 (49.7) |

| Glutenb | 72 (49.0) |

| White flour products | 69 (46.9) |

| Alcohol | 59 (40.1) |

| High fat foods | 55 (37.4) |

| Red meat | 54 (36.7) |

| Caffeine | 51 (34.7) |

| Tobacco | 47 (32.0) |

| Sodium/salt | 43 (29.3) |

| Shellfish | 38 (25.9) |

| Nightshadesc | 35 (23.8) |

| Pork | 31 (21.1) |

| Other | 20 (13.6) |

| Food categories that were added by participants, n (%) | N =135 |

| Vegetables | 84 (62.2) |

| Fish oil/Omega-3 | 80 (59.3) |

| Fruits | 78 (57.8) |

| Oral vitamin D | 65 (48.1) |

| Probiotics | 62 (45.9) |

| Organic foods | 43 (31.9) |

| Other | 14 (10.4) |

Candy and pastries, chocolate, French fries, potato chips, sweets.

Wheat, barley, rye products.

Tomatoes, eggplant, peppers, paprika, white potatoes.

Most of the survey participants (n =147, 87%) reported a trial of avoiding or reducing the following food categories from their diet: junk foods (candy and pastries, chocolate, French fries, potato chips, sweets; n =100, 68%), dairy (n =73, 49.7%), gluten (wheat, barley, rye products, n =72, 49%), white flour products (n =69, 46.9%), alcohol (n =59, 40.1%), high fat foods (n =55, 37.4%), red meat (n =54, 36.7%), caffeine (n =51, 34.7%), tobacco (n =47, 32%), sodium/salt (n =43, 29.3%), shellfish (n =38, 25.9%), nightshades (tomatoes, eggplant, peppers, paprika, white potatoes, n =35, 23.8%), pork (n =31, 21.1%) and other (n =20, 13.6%). Similarly, most of the survey respondents (n =135, 79.9%) noted a trial of adding the following foods to their diet: vegetables (n =84, 62.2%), fish oil/omega-3 (n =80, 59.3%), fruits (n =78, 57.8%), oral vitamin D (n =65, 48.1%), probiotics (n =62, 45.9%), organic foods (n =43, 31.9%) and other (n =14, 10.4%).

Special diets

Among all of the survey respondents, 63 respondents (37.3%) reported trying a special diet (e.g. vegetarian diet, gluten-free, Mediterranean, Ornish, South Beach, Paleo, Atkins, etc.). The most common diets tried were a gluten free diet (n =25, 39.7%), vegetarian diet (n =17, 27%), Paleo (n =11, 17.5%), low carb diet (n =9, 14.2%), dairy free diet (n =8, 12.7%), Atkins (n =7, 11.1%), Mediterranean diet (n =3, 4.7%), South beach (n =1, 1.6%) and other (n =4, 6.3%). On the whole, the mean (SD) diet length was 17.7 (45.9) months and 60.3% of patients (n =38) reported weight loss on these diets.

Responses/outcomes to dietary modifications

Perceived improvement in skin disease after removing or adding the aforementioned foods by survey respondents is reported in Table 3. A positive response was reported in respondents removing the following foods: white flour products (37 of 69, 53.6%), gluten (37 of 72, 51.4%), nightshades (18 of 35, 51.4%), junk foods (51 of 100, 51%), alcohol (30 of 59, 50.8%), dairy (37 of 73, 50.7%), high fat foods (24 of 55, 43.6%), tobacco (19 of 47, 40.4%), shellfish (14 of 38, 36.8%), caffeine (17 of 51, 33.3%), pork (10 of 31, 32.2%), red meat (13 of 54, 24.1%) and sodium/salt (10 of 43, 23.2%). In addition, a positive response was noted when adding the following foods/supplements: vegetables (40 of 84, 47.6%), organic foods (17 of 43, 39.5%), fish oil/omega-3 (28 of 80, 35%), fruits (27 of 78, 34.6%), oral vitamin D (23 of 65, 34.4%) and probiotics (24 of 62, 28.7%).

Table 3.

Response/outcomes to dietary modifications.

| Response/outcomes to dietary modifications | Value |

|---|---|

| Positive responsea with removal of the following from the diet, n (%) | |

| White flour products | 37 of 69 (53.6) |

| Gluten | 37 of 72 (51.4) |

| Nightshades | 18 of 35 (51.4) |

| Junk foods | 51 of 100 (51.0) |

| Alcohol | 30 of 59 (50.8) |

| Dairy | 37 of 73 (50.7) |

| High fat foods | 24 of 55 (43.6) |

| Tobacco | 19 of 47 (40.4) |

| Shellfish | 14 of 38 (36.8) |

| Caffeine | 17 of 51 (33.3) |

| Pork | 10 of 31 (32.2) |

| Red meat | 13 of 54 (24.1) |

| Sodium/salt | 10 of 43 (23.2) |

| Positive response after the addition of the following to the diet, n (%) | |

| Vegetables | 40 of 84 (47.6) |

| Organic foods | 17 of 43 (39.5) |

| Fish oil/Omega-3 | 28 of 80 (35.0) |

| Fruits | 27 of 78 (34.6) |

| Oral vitamin D | 23 of 65 (34.4) |

| Probiotics | 24 of 62 (28.7) |

Full clearance or improvement of atopic dermatitis.

Special diets

Several patients reported disease improvement after trying a specific diet. The three most successful reported diets were dairy free diet (six of eight, 75%), Paleo diet (eight of 11, 72.7%) and a gluten free diet (13 of 25, 72.2%). Other diets reported to be relatively successful in AD improvement included a low carb diet (three of nine, 33.3%), vegetarian diet (five of 17, 29.4%) and Atkins (two of seven, 28.6%).

Attitudes or perceptions about diet

Patients were asked about barriers and difficulties encountered when modifying their diet, as well as their attitudes surrounding diet as a management strategy for their disease (Table 4). Of note, 61.5% of patients (n =104) found it very difficult or somewhat difficult to follow a special diet, with the most common difficulty reported as lack of willpower or that following a special diet was too limiting (n =45, 44.1%). Overall, 55% of patients (n =93) found it very time-consuming or somewhat time-consuming to follow a special diet and 56.8% of patients (n =96) found it very expensive or somewhat expensive to follow a special diet.

Table 4.

Attitudes or perceptions about diet.

| Survey questions regarding attitudes or perceptions about diet | N (%) |

|---|---|

| How difficult/burdensome is it to follow a special diet? | |

| Very difficult | 32 (18.9) |

| Somewhat difficult | 72 (42.6) |

| Not difficult | 35 (20.7) |

| Not applicable | 30 (17.8) |

| What difficulties did you encounter modifying your diet? | |

| Will power/too limiting | 45 (44.1) |

| Time/inconvenience | 20 (19.6) |

| Family/social pressures | 11 (10.7) |

| Dining out/travel | 22 (21.5) |

| Affordability | 8 (7.8) |

| Access | 11 (10.8) |

| How time-consuming is it to follow a special diet? | |

| Very time-consuming | 31 (18.3) |

| Somewhat time-consuming | 62 (36.7) |

| Not time-consuming | 45 (26.6) |

| Not applicable | 31 (18.3) |

| How expensive is it to modify your diet? | |

| Very expensive | 22 (13.0) |

| Somewhat expensive | 74 (43.8) |

| Not expensive | 43 (25.4) |

| Not Applicable | 30 (17.8) |

| What motivated you to try dietary modification for your skin condition? | |

| Other treatments failed | 72 (42.6) |

| Recommended by friends/family | 27 (16.0) |

| Recommended by other patients | 17 (10.1) |

| It is a natural method | 52 (30.8) |

| It might improve other health problems | 55 (32.5) |

| I have not tried a diet modification | 41 (24.3) |

| Other | 16 (9.5) |

| How important is it that physicians discuss with patients the role of diet in managing skin disease? | |

| Very important | 121 (71.6) |

| Somewhat important | 37 (21.9) |

| Minimally important | 6 (3.6) |

| Not important at all | 5 (3.0) |

| Have you ever discussed dietary changes with your dermatologist? | |

| Yes, I discussed dietary changes with my dermatologist | 55 (32.5) |

| No, I have not discussed dietary changes with my dermatologist | 78 (46.2) |

| I haven’t tried any dietary changes | 36 (21.3) |

| The importance of diet compared to other interventions or treatments for management of the Eczema | |

| Diet is more important than taking prescription medications | 61 (36.1) |

| Diet is more important than over-the-counter medications | 64 (37.9) |

| Diet is more important than complimentary medications | 54 (32.0) |

| Diet is more important than exercise | 52 (30.8) |

| Diet is more important than stress reduction | 19 (11.2) |

| Currently, what role is diet playing in managing your skin condition | |

| Skin condition complete controlled with diet | 1 (0.6) |

| Diet is helping significantly with skin condition | 29 (17.2) |

| Diet is helping slightly with skin condition | 44 (26.0) |

| Diet has no effect on skin condition | 18 (10.7) |

| Not sure how diet effects skin condition | 72 (42.6) |

| Other | 5 (3.0) |

| How did you learn about the foods/drink that affect your skin condition | |

| Family | 30 (17.8) |

| Friends | 20 (11.8) |

| Other patients | 17 (10.1) |

| Trial and error | 77 (45.6) |

| Internet | 76 (45.0) |

| TV | 6 (3.6) |

| Books | 27 (16.0) |

| Other | 25 (14.8) |

| Not applicable | 30 (17.8) |

The motivation for using diet as a means of improving AD varied among patients. Patients cited the following reasons: previous treatments failed (n =72, 42.6%), recommended by friends/family (n =27, 16%), recommended by other patients (n =17, 10.1%), diet is a natural method (n =52, 30.8%), diet may improve other health problems (n =55, 32.5%), as well as other miscellaneous reasons (n =16, 9.5%). About 24.3% of patients (n =41) reported that they had not tried any dietary modification.

Although 93.5% of patients (n =158) found it very important or somewhat important that physicians discuss with patients the role of diet in managing skin disease, only 32.5% had discussed dietary changes with their dermatologist; 11.8% (n =20) discussed dietary changes with their dermatologist prior to modifying their diet, 16.6% (n =28) during or after making a dietary change and 4.1% (n =7) discussed diet with their dermatologist but have not made dietary modifications. About 46.2% of respondents (n =78) did not discuss any dietary changes with their dermatologists prior to their dietary change.

We asked patients to rate the importance of diet compared to other interventions or treatments for management of their AD: 37.9% (n =64) reported that diet was more important than taking over-the-counter medications, 36.1% (n =61) reported that diet was more important than taking prescription medications, 32% of patients (n =54) reported that diet was more important than taking complementary medications, 30.8% (n =52) felt diet was more important than exercise and 11.2% (n =19) reported that diet is more important than stress reduction. Patients were also asked what role is diet playing in managing their skin condition: 42.6% (n =72) reported that they are not sure how diet affects their skin condition, 26% (n =44) noted that their diet is helping slightly with their skin condition, 17.2% (n =29) reported that diet is helping significantly with their skin condition and only one patient (0.6%) reported that his skin condition was fully controlled with diet; 10.7% (n =18) of patients think that diet has not effect on their skin condition.

The majority of the patients learned about the foods/drinks that affect their skin condition by either trial and error (n =77, 45.6%) or from the internet (n =76, 45%). About 39.6% of patients (n =55) learned about foods/drinks that affect their skin condition from family, friends or other patients. Only 3.6% (n =6) of the patients reported TV as the source of the information.

Discussion

Despite tremendous gains in understanding the pathogenesis and treatment of AD, many patients seek alternative and complementary therapies especially when standard treatments are non-effective or have undesired side effects (17). In this study, which focused on patient-reported outcomes, we report an extremely high number of patients pursuing dietary modifications. Our results are consistent with previous reports (12,13).

The most common food categories that were reported to be avoided/reduced in our study were junk foods and dairy products; about 68% of patients reported a trial of avoiding/reducing junk foods and the majority reported full clearance or improvement of their skin condition following this trial. Our data is in agreement with previous studies that reported an association between junk foods and increased prevalence and severity of AD (5,18). This association might be related directly to food additives that have been found to aggravate AD in a randomized control study (19), or indirectly, to obesity which is associated with impaired skin barrier function and chronic inflammatory state (20,21).

In our study, 49.7% of patient reported a trial of avoiding/ reducing dairy product from their diet with the majority reporting a full clearance or improvement following the elimination. Similarly, Atherton et al. reported a possible association between dairy products and the severity of AD (22). However, Bath-Hextall et al. conducted a Cochrane review of nine RCTs of dietary exclusions in AD patient, with six trials studying eggs and milk exclusions. They concluded that the evidence available lends little support to the use of elimination diets since the studies were too small and poorly reported. Overall, food elimination diets were not found to be beneficial and are not recommended in the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines (23,24).

While some dietary elements are posited to trigger AD, other foods have been suggested to improve the disease symptoms. For example, 59.3% of patients in our study added fish oil or omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to their diet and 35% reported an improvement in their skin condition following this addition. PUFA and PUFA rich foods such as cold-water fish and fish oils are thought to modulate the production of eicosanoids. Uncontrolled studies in healthy adults (25) and a meta-analysis of RCTs (26) have demonstrated that consumption of PUFA enriched fish oil reduces the conversion of free arachidonic acids to leukotriene B4, which plays a key role in inflammatory and atopic conditions (27). In addition, Fujii et al. recently tested mice that have been fed a diet with low PUFA and found that deficiency in n-6 PUFA is mainly responsible for AD like symptoms (28). Despite the above evidence, a meta-analysis of 34 placebo-controlled essential fatty acids (EFA) trials concluded that the effect of EFAs was negligible and that supplementation with EFA has no clinically relevant effect on the severity of AD (29).

Other foods that improved AD symptoms in our surveyed subjects are vegetables. Almost half of the patients in our study reported a full clearance or improvement of their AD following the addition of vegetables to their diet. Vegetables provide a wealth carotenoids, flavonoids, vitamins and minerals that have been inversely correlated with oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and C-reactive protein (30). Furthermore, vegetarian diet has been previously reported to ameliorate symptoms of AD through reduction of number of peripheral eosinophils and of PGE2 synthesis by monocytes (31). However, evidence on the direct effect of vegetables on disease activity remains inconclusive and further RCTs are required.

In addition to specific foods, study participants were surveyed about their response to dietary supplements. Vitamin D improved AD symptoms in 34.4% of survey respondents. This may be explained by the antiproliferative and immunomodulatory effects of the active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (32). Vitamin D also stimulates the production and the regulation of skin antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidins, and its deficiency might predispose patients with AD to skin superinfection by Staphylococcus aureus (33). The role of vitamin D supplementation in AD is controversial in the literature. Two recently published RCTs found that vitamin D supplementation significantly improved AD symptoms; however, one study failed to compare vitamin D with placebo (7), while the other only examined a specific population of children with winter-related AD (34). In contrast, two RCTs by Hata et al. and Sidbury et al. found no significant improvement with supplementation of vitamin D (35,36) and a 2008 Cochrane review concluded that studies were of poor quality and too small to provide conclusive evidence for the benefit of vitamin D supplements in AD. Surprisingly, even the recent guidelines for vitamin D supplementation in AD are not clear; while the AAD notes that there are insufficient data to recommend it, the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters (allergy and immunology groups) supports it (17,37).

Dietary supplementation of probiotics has been also suggested for improving the skin condition of AD patients. Probiotics are live microorganisms that modify the overall composition of the gut microbiota and potentially modulate the host immune response (23). The mechanism for alleviation of AD symptoms by probiotics harkens back to the hygiene hypothesis, whereby the early exposure to diverse gut microbiota steers the immune system away from a Th2 response and upregulates Th1 cytokine production (2,38). The association between probiotics and AD may also stem from the finding that the intestinal microbiota are different in those with and without AD (39). In our study, 45.9% of patients performed a trial of probiotic supplementation and 28.9% reported skin improvement following this trial. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis of 25 RCTs with 1599 infants, children and adults, found significant differences in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index favoring probiotics over the control (8). However, Cochrane review of 12 RCTs involving 785 patients included a variety of probiotic strains and found no significant difference in symptoms or disease severity compared to placebo. Considering the little evidence of the beneficial effect of probiotics in AD, the current AAD guidelines do not recommend the use of probiotics (lever of evidence II) (23).

Attitudes or perceptions about diet

Patient centered research has become an area of interest especially since the establishment of the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) in 2010 (40). Unfortunately, traditional medical research is not always able to address the questions and concerns of both patients and clinicians; patient centered research aims to fill this gap by directing studies that particularly address these concerns. Surveying patients regarding their attitudes or perceptions about diet gives the opportunity to investigate the individual and anecdotal perceptions of patients regarding the effect of diets on their skin condition. Although the majority of patients in our study noted that following a special diet is difficult, expensive and time consuming, three-quarters of the patients reported an actual trial of dietary modification (either elimination or supplementation). This extremely high number of patient pursuing dietary modifications is consistent with the literature (12,13) and highlights the significance of diet as a management tool in AD from the perspective of patients. Furthermore, this also presents a knowledge gap between the perspective of patients regarding the role of diet in AD and the evidenced-based literature.

Surprisingly, the literature reveals that patients may be receiving different opinions from different clinicians. While primary care providers and allergologists are convinced of the causative role of food in the onset and severity of AD, dermatologists are convinced of the contrary (41,42). These conflicting viewpoints combined with the failure and undesirable side effects of the standard treatments lead patients to explore alternative therapies such as elimination diets often without consulting a professional. For example, in this study, 93.5% of patients believed it was important that physicians discuss with them the role of diet in managing their skin disease. However, only 32.5% of patients had actually consulted their dermatologist regarding their dietary manipulations.

Limitations

Limitations of the study include the self-selecting nature of the survey, which restricts generalizability of the findings. Other barriers to generalizability include the predominance of female gender, white race and urban living respondents. Additionally, recall bias might decrease the reported incidence, so that the true figure for dietary modifications in this population may be even higher than that reported. Furthermore, the length of dietary modifications was not assessed as well as the quantitative reduction or addition of the specific dietary modification, which may be a contributing factor to variation in skin responses reported among respondents. For example, respondents reporting favorable skin responses may have undergone dietary modifications that were longer and stricter than respondents who did not report a favorable response.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate patient-reported outcomes and perceptions regarding the role of diet in AD in the adult population. This patient centered study highlights the significance of diet as a management tool in AD from the perspective of patients. Our study also raises the concern about unsupervised dietary manipulations that could potentially lead to nutrient deficiencies as previously reported (14–16,23). Since dietary modifications are extremely common, the role of diet in AD needs to be discussed with patients and proper medical supervision, nutritional counseling and supplementations should be included for patients pursuing prolonged dietary modifications. Undoubtedly, future research on patient-reported outcomes and more RCTs are necessary in order to assess best practices for diet in patients with AD.

Acknowledgments

Funding

W.L. is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (4R01AR065174-04, 5U01AI119125-02). W.L. is grateful for charitable funding from the Dinsmore family.

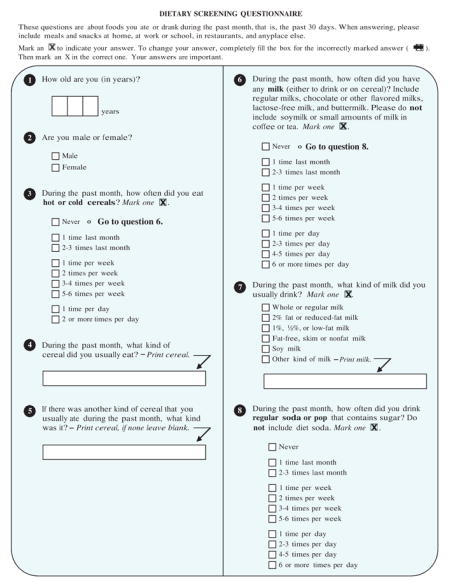

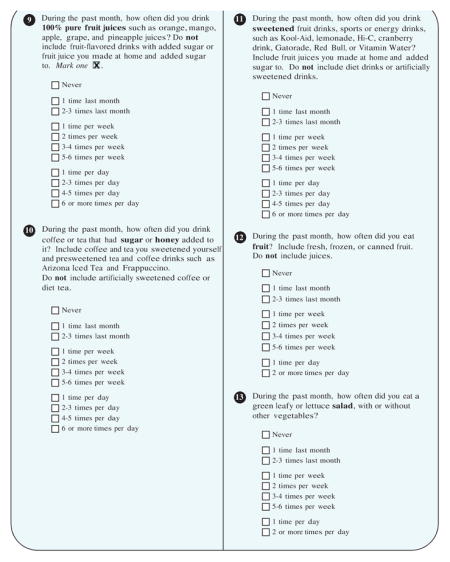

Appendix. DIETARY SCREENING QUESTIONNAIRE

These questions are about foods you ate or drank during the past month, that is, the past 30 days. W hen answering, please include meals and snacks at home, at work or school, in restaurants, and anyplace else.

Mark an

to indicate your answer. To change your answer, completely fill the box for the incorrectly marked answer (

to indicate your answer. To change your answer, completely fill the box for the incorrectly marked answer (

). Then mark an X in the correct one. Your answers are important.

). Then mark an X in the correct one. Your answers are important.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest. There have been no prior presentations of this material.

References

- 1.Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:67–73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantor R, Silverberg JI. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;1:15–26. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1212660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deckers IA, Deckers IAG, McLean S, et al. Investigating international time trends in the incidence and prevalence of atopic eczema 1990–2010: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for established atopic eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD005203. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005203.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park S, Choi HS, Bae JH. Instant noodles, processed food intake, and dietary pattern are associated with atopic dermatitis in an adult population (KNHANES 2009–2011) Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25:602–13. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.092015.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bath-Hextall FJ, Jenkinson C, Humphreys R, Williams HC. Dietary supplements for established atopic eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD005205. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005205.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amestejani M, Salehi BS, Vasigh M, et al. Vitamin D supplementation in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a clinical trial study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:327–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SO, Ah Y-M, Yu YM, et al. Effects of probiotics for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:217–26. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viljanen M, Savilahti E, Haahtela T. Probiotics in the treatment of atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome in infants: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2005;60:494–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle RJ, Bath-Hextall FJ, Leonardi-Bee J. Probiotics for treating eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD006135. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006135.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborn DA, Sinn JK. Probiotics in infants for prevention of allergic disease and food hypersensitivity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD006475. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006475.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RA. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webber SA, Graham-Brown RA, Hutchinson PE, Burns DA. Dietary manipulation in childhood atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:91–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barth GA, Weigl L, Boeing H, et al. Food intake of patients with atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Kwon J, Noh G, Lee SS. The effects of elimination diet on nutritional status in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7:488–94. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2013.7.6.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverberg NB, Lee-Wong M, Yosipovitch G. Diet and atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2016;97:227–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vieira BL, Lim NR, Lohman ME, Lio PA. Complementary and alternative medicine for atopic dermatitis: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;6:557–81. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellwood P, Asher MI, García-Marcos L, et al. Do fast foods cause asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema? Global findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) phase three. Thorax. 2013;68:351–60. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Worm M, Ehlers I, Sterry W, Zuberbier T. Clinical relevance of food additives in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:407–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang A, Silverberg JI. Association of atopic dermatitis with being overweight and obese: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:606–16. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:415–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atherton DJ, Sewell M, Soothill JF, et al. A double-blind controlled crossover trial of an antigen-avoidance diet in atopic eczema. Lancet. 1978;1:401–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bronsnick T, Murzaku EC, Rao BK. Diet in dermatology: Part I. Atopic dermatitis, acne, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1039e1–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turini ME, Powell WS, Behr SR, Holub BJ. Effects of a fish-oil and vegetable-oil formula on aggregation and ethanol-amine-containing lysophospholipid generation in activated human platelets and on leukotriene production in stimulated neutrophils. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:717–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang J, Li K, Wang F. Effect of marine-derived n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on major eicosanoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis from 18 randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chari S, Clark-Loeser L, Shupack J, Washenik K. A role for leukotriene antagonists in atopic dermatitis? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:1–6. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujii M, Nakashima H, Tomozawa J, et al. Deficiency of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids is mainly responsible for atopic dermatitis-like pruritic skin inflammation in special diet-fed hairless mice. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:272–7. doi: 10.1111/exd.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Gool CJ, Zeegers MP, Thijs C. Oral essential fatty acid supplementation in atopic dermatitis—a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:728–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0007-0963.2004.05851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holt EM, Steffen LM, Moran A, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and its relation to markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Kouda K, Kotani M. Vegetarian diet ameliorates symptoms of atopic dermatitis through reduction of the number of peripheral eosinophils and of PGE2 synthesis by monocytes. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2001;20:353–61. doi: 10.2114/jpa.20.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szekely JI, Pataki A. Effects of vitamin D on immune disorders with special regard to asthma, COPD and autoimmune diseases: a short review. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6:683–704. doi: 10.1586/ers.12.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vestita M, Filoni A, Congedo M, et al. Vitamin D and atopic dermatitis in childhood. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:257879. doi: 10.1155/2015/257879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camargo CA, Jr, Ganmaa D, Sidbury R. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:831–5. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hata TR, Audish D, Kotol P. A randomized controlled double-blind investigation of the effects of vitamin D dietary supplementation in subjects with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:781–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sidbury R, Sullivan AF, Thadhani RI, Camargo CA. Randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in Boston: a pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:245–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohan GC, Lio PA. Comparison of dermatology and allergy guidelines for atopic dermatitis management. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1009–13. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Aa LB, Heymans HS, van Aalderen WM, Sprikkelman AB. Probiotics and prebiotics in atopic dermatitis: review of the theoretical background and clinical evidence. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:e355–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penders J, Thijs C, van den Brandt PA, et al. Gut microbiota composition and development of atopic manifestations in infancy: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Gut. 2007;56:661–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312:1513–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Getmetti C. Diet and atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:439–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suh KY. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: separating fact from fiction. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]