Abstract

Gorham-Stout Disease (GSD) is a rare lymphatic disorder affecting children or young adults with no predilection of sex. It is generally associated with vanishing bone osteolytic lesions, thoracic and abdominal involvement, and diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Chylous effusions and chylothorax, consequent to the abnormal proliferation of lymphatic vessels, may induce respiratory failure with a high mortality risk. Extrapulmonary alterations may include chylous ascites, lymphopenia, and destructing bone disease for overgrowth of lymphatic vessels. Here, we report the case of a young woman who developed a severe and recalcitrant GSD with persistent unilateral chylothorax during pregnancy. The complex management of this patient during and after pregnancy was discussed and compared with literature data to contribute to the definition of a correct diagnostic and therapeutic approach to this rare lymphatic disease.

Keywords: gorham-stout disease, pregnancy, lung, treatment

Hellyver et al reported one year ago, an interesting case of Gorham-Stout Disease (GSD) in a young female during pregnancy. 1 This case report helped us to manage a similar complex case of a young woman who presented an acute onset of GSD in the 25th pregnancy week with unilateral lung involvement. This rare lymphatic disorder generally occurs in children or young adults with no predilection of sex. 2 3 It is generally associated with vanishing bone osteolytic lesions, and thoracic and abdominal involvement with diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. 2 Chylous effusions and chylothorax, consequent to the abnormal proliferation of lymphatic vessels may induce respiratory failure with a high mortality risk. 4 5 6 Extrapulmonary alterations may include chylous ascites, lymphopenia, and destructing bone disease for overgrowth of lymphatic vessels. 4 5 6 7 The pathogenesis of the disease is unclear and the prognosis is related to disease localizations. The therapeutic approach to this rare disease includes surgical procedures (such as thoracic duct ligation for chylothorax, drainages, etc.), support therapies (such as albumin transfusion, oxygen therapy, low-fat medium-chain triglyceride diets), and pharmacological approaches (tamoxifen, interferon-α, radiation, systemic steroids, hormones, oncologic drugs, somatostatin, bevacizumab, and sirolimus); however, no drug has been correctly validated until now. 3 7 8 9 10 11 12 Bilateral lung transplantation can be a therapeutic option in selected cases. 11

Case Presentation

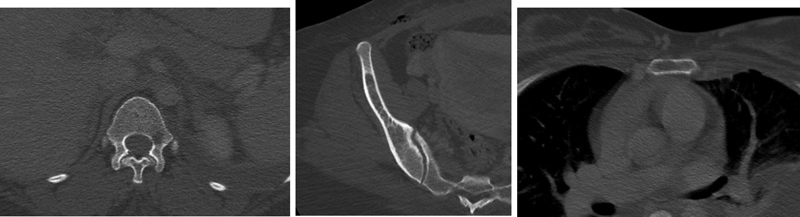

Here, we report the case of a young woman who developed a severe and recalcitrant GSD with persistent unilateral chylothorax during pregnancy. The complex management of this patient during and after pregnancy was discussed and compared with literature data to contribute to the definition of a correct diagnostic and therapeutic approach to this rare disease. A 32-year-old African woman, in her 25th pregnancy week, was admitted to our hospital referring acute dyspnea at rest and severe nocturnal orthopnea. The patient had no fever or cough but she referred acute chest pain. She already had three previous pregnancies without complications. Because of the dyspnea persistence and the abolition of left lung breath sound on physical examination, a chest X-ray was performed revealing left pleural effusion. The thoracentesis allowed the drainage of 1900 cc of a milky fluid. The pleural fluid analysis consisted of chylothorax, that unfortunately continued to re-form (more than 700 ml/day), requiring maintenance of the drainage. An interdisciplinary meeting involving also the gynecologists was organized to take a therapeutic decision, as the risk of surgery in that phase of pregnancy was too high as well as the introduction of immunosuppressive pharmacological drugs (at high risk for the fetus). In the 30th pregnancy week, ultrasounds revealed an intrauterine growth retardation with flowmeter alterations. Thus, a caesarean delivery was performed and a 1.8 kg baby girl was born. Placenta histology revealed minimal focal inflammation of the membranes with numerous vessel ectasia of the chorionic villi. The patient continued to discharge abundant milky fluid from her drainage, and postpartum highresolution CT scans of the chest and abdomen were performed, revealing diffuse interlobular and peribronchial septal thickening with left pleural effusion, no mediastinal lymph node enlargement, but several mediastinal cysts ( Figs. 1 2 3 4 ). The liver appeared enlarged, multiple cystic areas were observed in the spleen, and abundant fluid groundwater was observed in the pelvic cavity and perirenal areas. Multiloculated fluid density cysts in lomboaortic region were observed, as well as rarefaction lesions of sternum and D12 vertebra. Antinuclear autoantobodies were positive although, rheumatologic consultation did not reveal abnormalities; blood quantiferon and microbiological cultures were negative as well as all serological biomarkers of infection and albumin concentrations in serum were low. Unfortunately, the patient continued to be tachypneic and tachycardic. The treatment strategy for pleural effusion was established. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) was performed for diagnostic reason to do parietal pleural biopsies, and for therapeutic purposes to perform talc pleurodesis with scarification. But the patient continued to deteriorate requiring further surgical approach for lung decortication and diaphragmatic plication. This last procedure was performed because the chylous was sparing from diaphragmatic pleurocysts (resembling lymphangiomas) that were biopsied. The patient fasted for 10 days after surgery receiving only total parenteral nutrition with a < 5 g oral fat diet followed by a low-fat medium-chain triglyceride diet and octreotide injections. Microscopic examination showed extensive acute and chronic inflammation of parietal and diaphragmatic pleura with giant cells and proliferative lymphatic channels with angioectasia and without cytological atypia. Reactive mesothelial hyperplasia was described, immunohistochemistry for calretinin, CK7, CK5/6, Estrogen Receptor (ER) and Progesterone Receptor (PR) testing was performed, and lymphatic vessels alterations were documented. The patient was discharged with a diagnosis of GSD. Actually, she is alive, she has had a healthy daughter but she needs specific treatments such as steroids, low-fat medium-chain fat diet, and anti-inflammatory drugs for the persistence of dyspnea, chest pain, and minimal pleural effusion.

Fig. 1.

Small lytic lesions of the vertebra (D12), pelvis (right iliac wing), and stern um.

Fig. 2.

Multiloculate cystic fluid density mass (lymphangiomas) in the anterior mediastinum.

Fig. 3.

(A) Peribronchovascular and interlobular interstitial thickening and pleural thickening in the left lung, and (B) Left chylous pleural effusions.

Fig. 4.

Multiple, low attenuation, rounded lesions of the spleen.

Discussion

The features of this case include the onset of GSD during pregnancy, and the unilateral chylothorax consequent to thoracic vertebrae and sternum involvement. In this pregnant patient, the lymphatic invasion into the pleural cavity seems to be induced by bone GSD involvement, hormonal stimuli, and by the increase of intra-abdominal pressure associated with chylous ascites. The hormonal stimuli may have had a role as the patient was in the 25th pregnancy week of her fourth pregnancy when she developed GSD, analogously to a similar case published in your journal. 1 The main difference was that in the already published case, a prenatal diagnosis of GSD was done many years ago and the woman developed an acute disease phase, with severe recalcitrant chylothorax during the fourth pregnancy week; she was treated using a more conservative approach compared to our patient, as the chylothorax was discovered at the beginning of the pregnancy. 1 Hellyver and coauthors wondered about the possibility that female hormones produced during pregnancy can trigger this exacerbation. 1 12 Perhaps, our case supports the suspicion that pregnancy may trigger chylothorax in GSD together with changes in intrathoracic pressure, as suggested for idiopathic chylothorax occurring during pregnancy. 10 12 13 14 15 No pathogenetic studies have been performed to verify the potential role of estrogens in lymphatic alterations and bone cellular metabolism occurring in GSD during pregnancy. 1 In our patient as well as in the one previously described, low oral fat diet together with total parenteral nutrition gave positive effects, while octreotide therapy proved ineffective only in our patient and not in the other cases. 1 12 13 14 15

In conclusion, the present case study illustrates an unusual presentation of GSD during pregnancy underlining the difficulties in the management of this disease to guaranty good fetal and mother evolution. Further studies are required to improve the limited therapeutic options of this rare disease.

References

- 1.Hellyer J, Oliver-Allen H, Shafiq M et al. Pregnancy complicated by Gorham-Stout Disease and refractory chylothorax. AJP Rep. 2016;6(04):e355–e358. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kose M, Pekcan S, Dogru D et al. Gorham-Stout Syndrome with chylothorax: successful remission by interferon alpha-2b. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(06):613–615. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim H J, Han J, Kim H K, Kim T S. A rare case of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis in a middle-aged woman. Korean J Radiol. 2014;15(02):295–299. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2014.15.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itkin M, McCormack F X. Nonmalignant Adult Thoracic Lymphatic Disorders. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37(03):409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renacci R M, Bartolotta R J. Gorham disease: lymphangiomatosis with massive osteolysis. Clin Imaging. 2017;41:83–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao J, Wu R, Gu Y. Pathology analysis of a rare case of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(06):114–116. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.03.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinnier C V, Eu J P, Davis R D, Howell D N, Sheets J, Palmer S M. Successful bilateral lung transplantation for lymphangiomatosis. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(09):1946–1950. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takemura T, Watanabe M, Takagi K, Tanaka S, Aida S. Thoracoscopic resection of a solitary pulmonary lymphangioma: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25(07):651–653. doi: 10.1007/BF00311443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satria M N, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Moss J. Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Lymphat Res Biol. 2011;9(04):191–193. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2011.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schild H H, Strassburg C P, Welz A, Kalff J. Treatment options in patients with chylothorax. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(48):819–826. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aman J, Thunnissen E, Paul M A, van Nieuw Amerongen G P, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Successful treatment of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis with bevacizumab. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):839–840. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gambling D R, Catanzarite V, Fisher J, Harms L. Anesthetic management of a pregnant woman with Gorham-Stout disease. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2011;20(01):85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter K B, O'Brien W F, Towsley G, Cates J D, Watts D B.Pregnancy complicated by Gorham disease Obstet Gynecol 199381(5 ( Pt 2)):808–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkley E M, Gill G J, Moore L E, Rayburn W F. Consumptive coagulopathy associated with Gorham syndrome and subsequent Kasabach-Merritt syndrome during pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(12):1103–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellyer J, Oliver-Allen H, Shafiq M et al. Erratum: Pregnancy Complicated by Gorham-Stout Disease and Refractory Chylothorax. AJP Rep. 2016;6(04):e384. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]