Abstract

Oral epithelial cells discriminate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic stimuli, and only induce an inflammatory response when they are exposed to high levels of a potentially harmful microorganism. The pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in epithelial cells that mediate this differential response are poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that the ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EphA2) is an oral epithelial cell PRR that binds to exposed β-glucans on the surface of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Binding of C. albicans to EphA2 on oral epithelial cells activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in an inoculum-dependent manner, and is required for induction of a pro-inflammatory and antifungal response. EphA2−/− mice have impaired inflammatory responses and reduced IL-17 signaling during oropharyngeal candidiasis, resulting in more severe disease. Our study reveals that EphA2 functions as PRR for β-glucans that senses epithelial cell fungal burden and is required for the maximal mucosal inflammatory response to C. albicans.

Oral epithelial cells are continuously exposed to a multitude of antigens derived from food and the resident bacterial and fungal microbiota. They must be able to discriminate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic stimuli so that an inflammatory response is induced only when the epithelial cells are exposed to high levels of a potentially harmful microorganism. The interactions of oral epithelial cells with the fungus Candida albicans provides an example of this paradigm. As part of the normal microbiota of the gastrointestinal and reproductive tracts of healthy individuals 1, this organism elicits a minimal epithelial cell response during commensal growth, when a low number of organisms is present. However, when local or systemic host defenses are weakened, C. albicans can proliferate and cause oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), an infection that is highly prevalent in patients with HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and iatrogenic or autoimmune-induced dry mouth 2. When OPC occurs, oral epithelial cells are activated to induce a pro-inflammatory response that plays a central role in limiting the extent of infection. For example, mice with an oral epithelial cell-specific defect in IL-17 receptor signaling or production of β defensin 3 are highly susceptible to OPC and unable to resolve the infection 3.

How oral epithelial cells discriminate between C. albicans when it grows as a commensal organism versus an invasive pathogen is incompletely understood. The fungus can interconvert between ovoid yeast and filamentous hyphae. C. albicans yeast are poorly invasive and weakly stimulate epithelial cells to release proinflammatory cytokines and host defense peptides (HDPs). In contrast, hyphae avidly invade epithelial cells and strongly stimulate the production of cytokines and HDPs 4–6. Mucosal epithelial cells express a variety of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that can potentially recognize C. albicans 7. These cells also express non-classical receptors such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), HER2, and E-cadherin that can recognize C. albicans hyphae 8–10. However, relatively little is known about PRRs in oral epithelial cells, even though these cells constitute a key barrier to mucosal infection.

Results

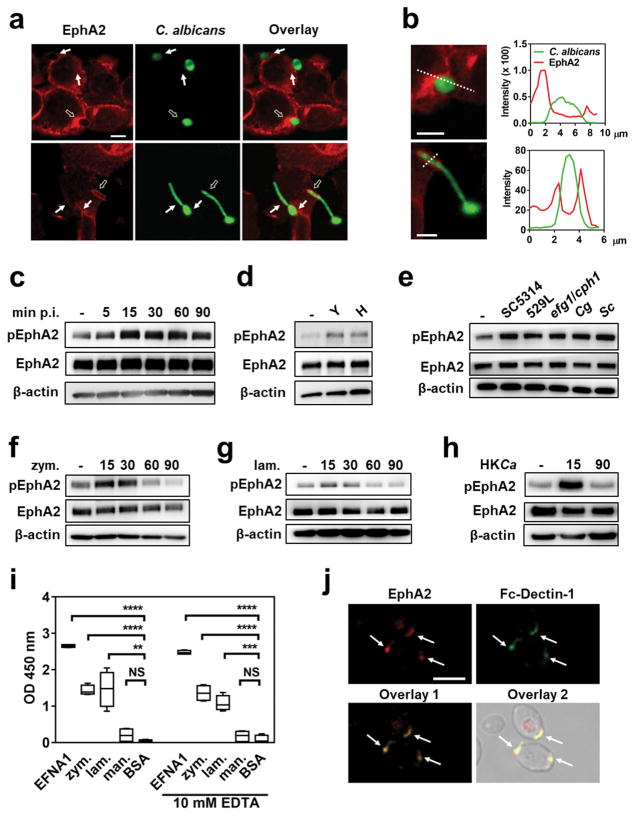

EphA2 is activated by fungal β-glucans

The ephrin type A receptor 2 (EphA2) is a receptor tyrosine kinase that induces both endocytosis and cytokine production by host cells 11,12. We investigated the hypothesis that EphA2 functions as an epithelial cell receptor for C. albicans. By confocal microscopic imaging of intact oral epithelial cells infected with C. albicans, we observed that EphA2 accumulated around yeast-phase cells after 15 min of infection and hyphae after 90 min (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1). To ascertain whether C. albicans activates EphA2, oral epithelial cells were infected with yeast-phase C. albicans cells and the extent of EphA2 phosphorylation was analyzed over time. EphA2 phosphorylation increased above basal levels within 15 min post-infection, when the organisms were still in the yeast phase (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2). EphA2 phosphorylation also remained elevated after 60 and 90 min of infection, when the organisms had formed hyphae. When epithelial cells were incubated for 15 min with either yeast- or hyphal-phase organisms, Epha2 phosphorylation was stimulated to the same extent, indicating that both forms of the organism can activate the receptor (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. EphA2 is bound and activated by β-glucans.

(a) Confocal microscopic images of OKF6/TERT-2 epithelial cells that had been infected with GFP expressing C. albicans (CAI4-GFP) and then stained for EphA2 (red). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Arrows indicate the accumulation of EphA2 around the fungal cells. Hollow arrows indicate organisms that were analyzed for fluorescent intensity in (b). Negative control images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 (b) Magnified image of C. albicans cells with plots of fluorescent intensity at the regions indicated by the dotted line. The green lines indicate the fluorescent intensity of GFP expressing C. albicans and the red lines indicate the fluorescent intensity of the EphA2. (c) Immunoblot analysis showing the time course of EphA2 phosphorylation in oral epithelial cells that had been infected with yeast-phase C. albicans SC5314 for the indicated times. (d) EphA2 phosphorylation after 15-min infection with either C. albicans yeast or pregerminated hyphae. H, hyphae; Y, yeast. (e) Effects of C. albicans (SC5314, 529L, efg1/cph1), Candida glabrata, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on EphA2 phosphorylation. Cg, C. glabrata; Sc, S. cerevisiae. (f–h) Time course (in minutes) of EphA2 phosphorylation induced by zymosan (f), laminarin (g), and heat-killed C. albicans SC5314 (HKCa) (h). (i) Binding of recombinant EphA2 to immobilized ephrin A1, zymosan, laminarin, mannan, and BSA, as determined by ELISA. Box whisker plots show median and range of 3 experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis of binding is shown relative to wells coated with BSA. EFNA1, ephrin A1; lam, laminarin; man, mannan; zym, zymosan (j) EphA2 (red) and Fc-dectin-1 (green) bind to exposed β-glucan on yeast-phase C. albicans. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Densitometric analyses of replicate immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2, 4a, 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant (two-tailed Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances). Scale bars 5 μm.

To determine the specificity of EphA2 signaling, we analyzed whether EphA2 phosphorylation could be induced by different microbial stimuli, including bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli), a clinical mucosal C. albicans isolate (529L), a yeast-locked C. albicans mutant (efg1/cph1), a non-invasive C. albicans mutant (als3/ssa1), a candidalysin-deficient C. albicans mutant (ece1) and different fungal species (Candida glabrata, Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Although neither S. aureus nor E. coli stimulated the phosphorylation of EphA2 (Supplementary Fig. 3), all fungi tested induced phosphorylation of this receptor within 15 min of infection (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that EphA2 is activated by a conserved fungal cell wall component. To test this possibility, we analyzed EphA2 activation by β-glucan and mannan, which are present in the cell walls of many fungi. Both particulate β-glucan (zymosan) and soluble β-glucan (laminarin) stimulated EphA2 phosphorylation after 15 and 30 min, and this phosphorylation returned to basal levels by 60 min (Fig. 1f, g, and Supplementary Fig. 5). Heat-killed C. albicans yeast, which have increased surface exposed β-glucan 13, also induced transient EphA2 activation (Fig. 1h, and Supplementary Fig. 5). By contrast, mannan, another cell wall component, failed to induce detectable EphA2 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 6).

To ascertain whether EphA2 interacts directly with β-glucans, we used an ELISA to analyze the binding of recombinant EphA2 to potential ligands. As expected, EphA2 bound to its natural ligand, ephrin A1 (EFNA1) (Fig. 1i). EphA2 also bound to zymosan and laminarin, but not to mannan in both the presence and absence of 10 mM EDTA, indicating that binding to β-glucans is independent of Ca2+. EGFR, another epithelial cell receptor for C. albicans, did not bind to zymosan (Supplementary Fig. 7). Consistent with the ELISA data, we found that recombinant EphA2 bound to intact yeast-phase C. albicans cells at regions of exposed β-glucan, as demonstrated by co-localization with Fc-Dectin-1 (Fig. 1j). EphA2 also bound to zymosan, and fluorescent-labeled zymosan bioparticles, as well as exposed β-glucan on other fungal pathogens, including Aspergillus fumigatus and Rhizopus delemar (Supplementary Fig. 8).

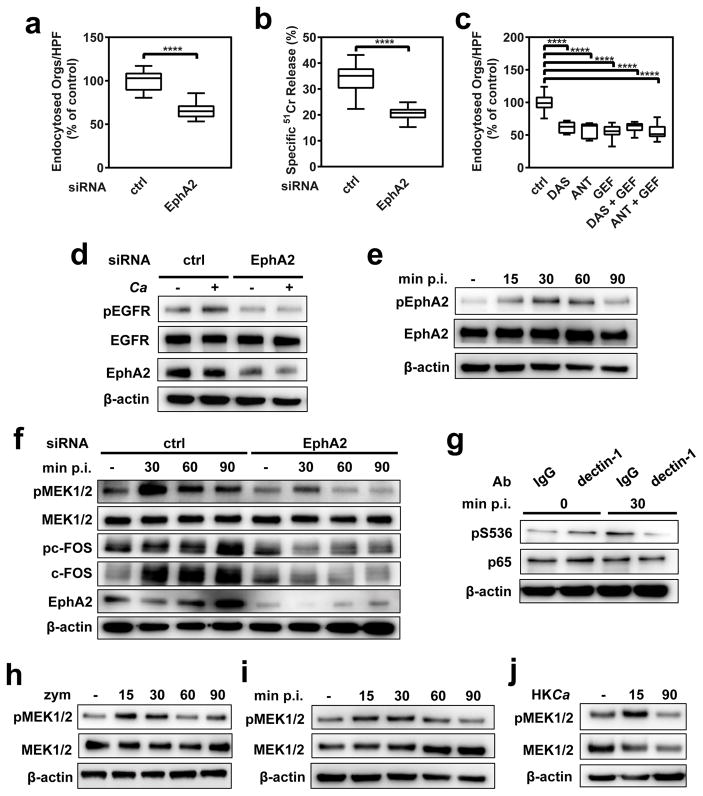

EphA2 functions in the EGFR endocytosis pathway

C. albicans hyphae can invade oral epithelial cells by receptor-induced endocytosis 10, and epithelial cell invasion is associated with fungal-induced epithelial cell damage 6. To determine the biological significance of EphA2 activation, we analyzed the effects of EphA2 siRNA, the small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor, dasatinib (DAS) 14, and an EphA2 antagonist, 4-(2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (ANT) 15 on C. albicans invasion and damage of epithelial cells. Depletion of epithelial cell EphA2 by siRNA significantly inhibited the endocytosis of C. albicans (Fig. 2a) and attenuated the extent of fungal-induced epithelial cell damage (Fig. 2b). Transfection with EphA2 siRNA had no effect on cellular levels of the ephrin receptors EphA4 or EphB2, while EphB2 siRNA had no effect on cellular levels of EphA2 or epithelial cell endocytosis of C. albicans (Supplementary Fig. 9). After verifying that DAS and ANT inhibited C. albicans-induced phosphorylation of EphA2 (Supplementary Fig. 10), we determined that both inhibitors also inhibited epithelial cell endocytosis and damage (Supplementary Fig. 11), but had no effect on C. albicans growth rate or hyphal elongation (Supplementary Table 1). The addition of EFNA1 to further stimulate EphA2 enhanced both endocytosis and damage (Supplementary Fig. 11), indicating that the extent EphA2 activation governs epithelial cell endocytosis of C. albicans and subsequent fungal-induced damage.

Fig. 2. EphA2 and dectin-1 regulate distinct host response pathways in oral epithelial cells.

(a–b) Effects of EphA2 depletion with siRNA on the endocytosis of C. albicans by oral epithelial cells (a) and extent of C. albicans-induced host cell damage (b). (c) Effects of inhibition of EphA2 with dasatinib or an EphA2 antagonist and/or inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) with gefitinib on the endocytosis of C. albicans by oral epithelial cells. Box whisker plots show median and range of three experiments, each performed in triplicate. (d) Effect of EphA2 siRNA on EGFR phosphorylation at Y1068 in oral epithelial cells infected with C. albicans. (e) Effect of inhibition of EGFR with gefitinib on the phosphorylation of epithelial cell EphA2 in response to C. albicans infection. (f) Immunoblots showing the effects of EphA2 siRNA on the phosphorylation of epithelial cell MEK1/2 and c-FOS in response to C. albicans. (g) Effect of treatment of epithelial cells with an anti-dectin-1 mAb on the phosphorylation of p65 S536 induced by C. albicans. (h) Time course (in min) of MEK1/2 phosphorylation induced by zymosan. (i) Effect of EGFR inhibition on MEK1/2 phosphorylation in response to C. albicans. (j) Transient MEK1/2 activation in response to heat-killed C. albicans. Densitometric analyses of replicate immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Figs. 12, 13a,c, 14, 17, 18).ANT, EphA2 antagonist; DAS, dasatinib; GEF, gefitinib; p.i., post-infection; HKCa, Heat-killed C. albicans; zym, zymosan. ****P < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances).

EGFR signaling is crucial for inducing the endocytosis of C. albicans by oral epithelial cells, and there is cross-talk between EphA2 and EGFR in some cancer cells 8,16,17. We analyzed the relationship between EGFR and EphA2 signaling during the endocytosis of C. albicans and found that inhibition of EphA2 with either DAS or ANT, and inhibition of EGFR with gefitinib 8 reduced the endocytosis of C. albicans by a similar amount (Fig. 2c). Simultaneous inhibition of both EphA2 and EGFR did not decrease endocytosis further. Also, EphA2 depletion with siRNA and inhibition of EphA2 signaling with DAS or ANT blocked C. albicans-induced EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 12), while inhibition of EGFR with gefitinib decreased EphA2 phosphorylation after 60 min (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 12). Collectively, these results suggest that a reciprocal interaction between EphA2 and EGFR governs the endocytosis of C. albicans.

EphA2 signaling is required for epithelial cell production of cytokines and host defense peptides

Contact with C. albicans yeast cells activates multiple signaling pathways in oral epithelial cells including mitogen-activated kinase regulated kinase (MEK) 1/2, p38, and NF-κB 18. We investigated whether EphA2 might function as a receptor that activates these signaling pathways. We determined that C. albicans stimulated the phosphorylation of MEK1/2 and p38-mediated phosphorylation of the c-Fos transcription factor within 30 min of infection (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 13). The phosphorylation of these proteins was maintained for at least 90 min and was inhibited by treatment of epithelial cells with EphA2 siRNA, DAS or ANT (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 13). Although C. albicans stimulated phosphorylation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB, this phosphorylation was not inhibited by DAS or ANT, suggesting that NF-κB activation is induced by a receptor other than EphA2 (Supplementary Fig. 13). One candidate receptor is the dectin-1 β-glucan receptor, which we determined was expressed on the surface of both the OKF6/TERT-2 oral epithelial cell line and desquamated human buccal epithelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 14). We found that a neutralizing dectin-1 mAb inhibited C. albicans-induced activation of p65 (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 15), but had no effect on the phosphorylation of EphA2 (Supplementary Fig. 16). These results suggest that during the epithelial cell response to C. albicans infection, dectin-1 is necessary for induction of NF-κB signaling, whereas EphA2 is required for activation of the MEK1/2 and p38 signaling pathways.

To investigate EphA2 signaling induced by β-glucan alone, we analyzed the response of epithelial cells to zymosan. While zymosan strongly activated MEK1/2 phosphorylation at 15 and 30 min, phosphorylation returned to basal levels by 60 min (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 17). Also, zymosan did not induce detectable c-Fos or p65 phosphorylation over the 90-min duration of the experiment (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 17). Exposure of oral epithelial cells to either live C. albicans in the presence of the EGFR inhibitor or heat-killed C. albicans alone induced a similar response—transient EphA2 and MEK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2i, j, Supplementary Fig. 18). Thus, EGFR and factor(s) expressed by live C. albicans are required to sustain EphaA2 and MEK1/2 signaling.

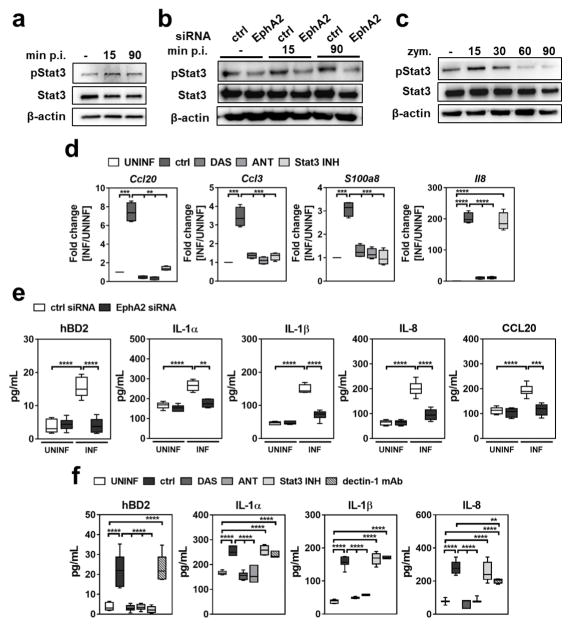

By secreting proinflammatory cytokines and HDPs, oral epithelial cells are vital for limiting fungal proliferation during OPC 19,20. The production of many of these factors is governed by the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) 19,21. We hypothesized that the interaction of C. albicans with EphA2 in oral epithelial cells would activate Stat3 and stimulate production of proinflammatory cytokines and HDPs. To test this, we determined the effects of EphA2 siRNA, DAS and ANT on Stat3 phosphorylation in epithelial cells. By both immunoblotting and ELISA, we found that C. albicans stimulated Stat3 phosphorylation within 15 min of infection and that blocking EphA2 with siRNA, DAS or ANT reduced C. albicans-induced Stat3 phosphorylation to basal levels (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 19). Although exposure to zymosan induced Stat3 phosphorylation within 15 min, this phosphorylation was transient, returning to basal levels after 30 min (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig.19). Treatment with DAS or ANT inhibited zymosan-induced activation of Stat3 (Supplementary Fig. 20). However, blockade of dectin-1 had no effect on Stat3 activation induced by either C. albicans or zymosan (Supplementary Fig. 20), suggesting that EphA2 is the primary β-glucan receptor that activates this transcription factor.

Fig. 3. EphA2 signaling regulates the inflammatory response.

(a) Immunoblot demonstrating that C. albicans infection induces phosphorylation of Stat3. (b) Effects of the EphA2 depletion with siRNA on C. albicans-induced phosphorylation of Stat3. (c) Time course of Stat3 phosphorylation induced by zymosan. Densitometric analyses of replicate immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 19. (d) Oral epithelial cells were incubated with inhibitors of EphA2 and Stat3 and then infected with C. albicans for 5 h, after which chemokines and the S100a8 alarmin mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR. Box whisker plots show median and range of 2 experiments, each performed in triplicate and are presented as fold induction relative to uninfected epithelial cells. (e) EphA2 depletion with siRNA reduces epithelial cell production of human β defensin 2, cytokines and chemokines in response to 8 h of C. albicans infection. Box whisker plots show median and range of 3 experiments, each performed in duplicate. (f) Regulation of the oral epithelial cell pro-inflammatory response to C. albicans by Stat3 and dectin-1. Box whisker plots show median and range of 3 experiments, each performed in duplicate. ANT, EphA2 antagonist; ctrl, control; DAS, dasatinib; hBD2, human β defensin 2; MOI, multiplicity of infection; Stat3 INH, Stat3 inhibitor; UNINF, uninfected. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; (two-tailed Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances).

By inhibiting EphA2 signaling with DAS or ANT or Stat3 signaling with S31-201 22, we found that the EphA2-Stat3 axis regulates C. albicans-induced mRNA expression of the chemokines Ccl20 and Ccl3, and the alarmin S100a8 in vitro (Fig. 3d). It also governs the secretion of human β-defensin 2 (hBD2) (Fig. 3e, f). Although inhibiting EphA2 with siRNA, DAS or ANT reduced Il8 mRNA expression and secretion of IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, and CCL20, inhibition of Stat3 did not (Fig. 3d–f). Thus, these responses are induced by EphA2 independently of Stat3. Treatment of epithelial cells with DAS or ANT did not inhibit production of IL-8 induced by TNF-α and IL-17 (Supplementary Fig. 21), indicating that these inhibitors only blocked the epithelial cell response to certain stimuli.

The addition of zymosan to the epithelial cells did not induce secretion of IL-8 or hBD2 (Supplementary Fig. 22), suggesting that although β-glucan-induced EphA2 activation is required to prime epithelial cells, a second signal is necessary to prolong EphA2 activation and stimulate cytokine and HDP release. Dectin-1, another β-glucan receptor 23,24, played limited role in the epithelial cell response to C. albicans; an anti-dectin-1 antibody had no effect on the release of hBD2, IL-1α, or IL-1β by infected epithelial cells, although it did cause a modest reduction in IL-8 release (Fig. 3f).

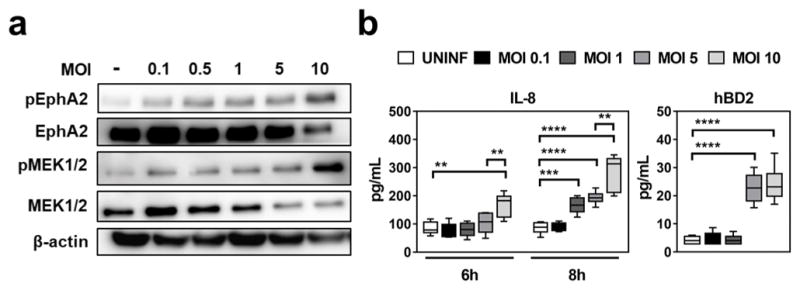

We investigated whether the extent of EphA2 activation governed the epithelial cell response to infection with different inocula of C. albicans. We found that while there was a gradual increase in the extent of EphA2 phosphorylation as the multiplicity of infection (MOI) increased from 0.1 to 5 organisms per epithelial cell, EphA2 phosphorylation dramatically increased at a MOI of 10 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 23). Low level phosphorylation of MEK1/2 was also stimulated by C. albicans yeast at a MOI of 0.1 to 1, whereas phosphorylation increased exponentially at MOIs of 5 and 10 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 23). Phosphorylation of Epha2 was blocked by DAS and ANT at all MOIs (Supplementary Fig. 23). The increased phosphorylation of EphA2 and MEK1/2 at high MOIs corresponded with enhanced secretion of IL-8 and hBD2 (Fig. 4b). Thus, while low inocula of C. albicans induce modest EphA2 activation and a minimal inflammatory response, higher inocula highly activate EphA2, leading to a strong inflammatory response.

Fig. 4. Higher fungal inoculum induces stronger host response.

(a) Immunoblots showing the effects of increasing C. albicans inoculum on the extent of EphA2 phosphorylation. Densitometric analyses of replicate immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 23. (b) Effects of C. albicans inoculum on epithelial cell secretion of IL-8 and hBD2. Box whisker plots show median and range of 3 independent experiments in duplicates. ctrl, control; hBD2, human β defensin 2; MOI, multiplicity of infection; Stat3 INH, Stat3 inhibitor; UNINF, uninfected. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; (two-tailed Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances).

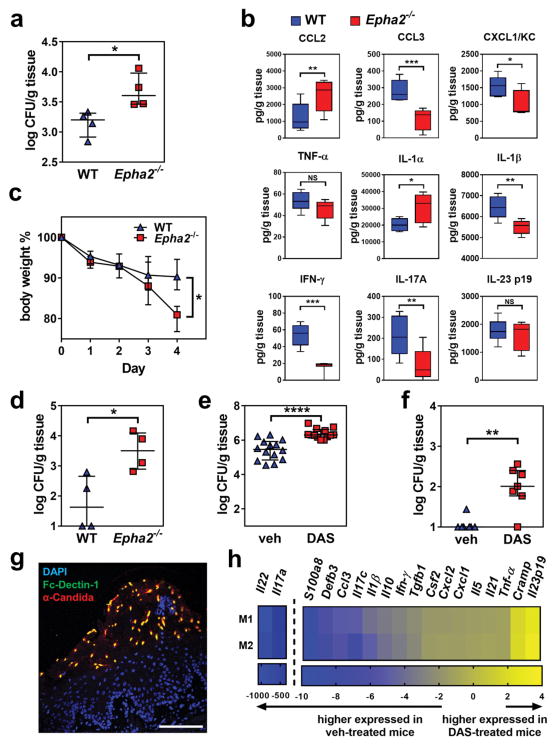

EphA2 signaling contributes to the host defense against OPC

To determine the biological significance of EphA2 as an oral mucosal β-glucan receptor for C. albicans in vivo, we induced OPC in EphA2−/− mice 25,26. After 1 d of infection, the EphA2−/− mice had a significantly higher oral fungal burden than the wild-type mice (Fig. 5a). The oral tissues of EphA2−/− mice contained lower levels of CCL3, CXCL1/KC, IL-1β, IFN-γ and IL-17A, and higher levels of CCL2 and the cell damage-associated alarmin IL-1α relative to the wild-type mice (Fig. 5b). The levels of TNF-α, CCL4, and vascular endothelial cell growth factor in the oral tissues were similar between the EphA2−/− and the wild-type mice (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 24). The severity of OPC in the EphA2−/− mice was increased further when they were immunosuppressed with low-dose triamcinolone (7 mg/kg). After 4 d of infection, these mice had greater weight loss and much higher oral fungal burden relative to wild-type mice (Fig. 5c, d). We also tested the effects of inhibiting EphA2 with DAS in wild-type mice that were immunosuppressed with higher-dose triamcinolone (15 mg/kg). Mice that received DAS had greater weight loss (Supplementary Fig. 25) and higher oral fungal burden relative to the animals that received the vehicle control (Fig. 5e). Histopathological analysis of the tongues of DAS-treated mice confirmed that inhibition of EphA2 signaling resulted in larger fungal lesions and deeper tissue invasion (Supplementary Fig. 25). Mice treated with DAS also had greater fungal dissemination to the liver, suggesting that EphA2 is required for maintaining the epithelial barrier function of the GI tract (Fig. 5f). When the fungal lesions on the tongues of the vehicle control mice were incubated with Fc-Dectin-1, many of the fungal cells were stained, indicating that β-glucan is exposed on the fungal surface during OPC (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 26). Consistent with our in vitro results, we found that C. albicans infection of the vehicle control mice induced strong Stat3 phosphorylation in the oral epithelium, and this phosphorylation was reduced by treatment with DAS (Supplementary Fig. 25). Administration of DAS also reduced Il17a mRNA expression in the oral tissues by 350-fold, Il22 mRNA by 1000-fold, S100a8 mRNA by 9-fold and Defb3 mRNA by 7-fold (Fig. 5h). Collectively, these results indicate that EphA2 signaling is necessary for a maximal IL-17 response during OPC. Thus, EphA2 is a key regulator of the host inflammatory response to C. albicans that limits fungal proliferation during oral infection.

Fig. 5. EphA2 signaling maintains mucosal immunity during OPC.

(a) Oral fungal burden of immunocompetent wild-type and EphA2−/− mice with oropharyngeal candidiasis after 1 d of infection. Results are median ± interquartile range of 4 mice per group in a single experiment. *P < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney Test) (b) Level of chemokines and cytokines in the tongue homogenates of immunocompetent wild-type and EphA2−/− mice with OPC after 1 d of infection. Box whisker plots show median and range of 4 mice in each group, tested in duplicate in a single experiment. (c) Body weight wild-type and EphA2−/− mice that were immunosuppressed with triamcinolone (7 mg/kg) prior to oral infection with C. albicans. Results are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 (Holm-Sidak method). (d) Oral fungal burden of triamcinolone treated (7 mg/kg) wild-type and EphA2−/− mice after 4 d of infection (e–h). Wild-type mice were immunosuppressed with triamcinolone (15mg/kg), treated with either DAS or the vehicle control, and orally inoculated with C. albicans. They were analyzed after 4 d of infection. (e) Oral fungal burden. Results are the median ± interquartile range of combined data from 2 independent experiments for a total of 14 mice in the control group and 13 mice in the DAS group. ****P < 0.0001 (Mann-Whitney Test) (f) Liver fungal burden. Results are median ± interquartile range of 7 mice per group in a single experiment. **P < 0.01 (Mann-Whitney Test) (g) Immunohistochemistry of the tongue of a control mouse showing that β-glucan is expressed on the fungal cell surface during oropharyngeal candidiasis. The tongue was stained with Fc-Dectin-1 (green), an anti-Candida antibody (red), and DAPI (blue) Scale bar 100 μm. Results are representative of 3 mice from the same experiment. (h) mRNA expression of the indicated inflammatory mediators in the mouse tongue after 4 d of infection. mRNA levels were determined by ΔΔCT method and normalized to GAPDH. Results are presented as fold change relative to the vehicle control mice. Data from two mice (M1 and M2) are presented. DAS, dasatinib; Veh, vehicle; WT, wild type.

Discussion

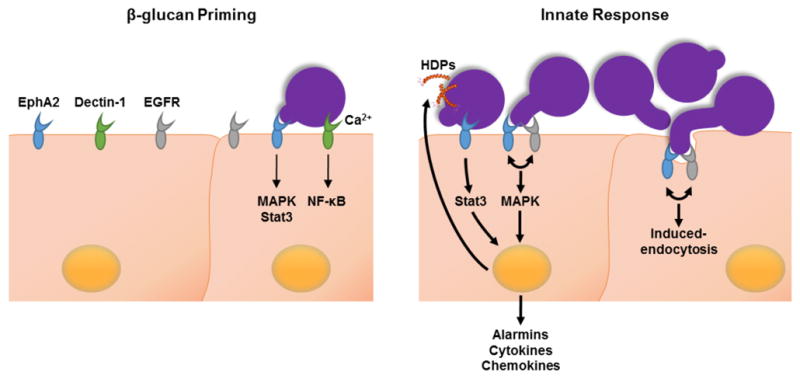

The data presented herein indicate that EphA2 is a non-classical receptor for β-glucans that plays a vital role in sensing the presence of C. albicans yeast and hyphae in the oral cavity. While EphA2 contributes to receptor-induced endocytosis of the organism, this function is overshadowed by the central role of EphA2 in sensing the presence of high levels of fungal β-glucans and activating MAPKs and Stat3, thereby stimulating epithelial cells to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and HDPs. In vivo, β-glucan recognition of invading fungi via EphA2 is also required for the production of IL-17, IL-22, and β-defensin 3, which are essential for resistance to OPC 20,27,28. Thus, our data support the model that EphA2 recognizes β-glucans expressed by pathogenic fungi and thereby primes epithelial cells to respond appropriately and prevent OPC when the fungal inoculum increases above threshold levels (Fig. 6). The finding that EphA2 binds to β-glucans of other fungi, such as C. glabrata, A. fumigatus, and R. delemar, suggests that this receptor also senses the presence of these organisms and induces specific host responses.

Fig. 6. Epha2 on oral epithelial cells binds β-glucan and primes the cells for an inflammatory response.

(Left panel) EphA2 (blue) and dectin-1 (green) bind to exposed β-glucan on the fungal surface. Binding to EphA2 is independent of Ca2+ and activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3). Binding to dectin-1 requires Ca2+ and activates nuclear factor ‘kappa-light-chain-enhancer’ of activated B-cells (NF-κB). (Right panel) During fungal proliferation, prolonged activation of EphA2 via EGFR (grey) induces the endocytosis of C. albicans and a pro-inflammatory response in the epithelial cells. EphA2-EGFR induces endocytosis and triggers MAPK signaling. EphA2 also activates Stat3 Activation of the Stat3 and MAPK pathways leads to the release of alarmins, cytokines, chemokines, and host defense peptides (HDPs, orange helix).

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute.

Fungal strains, cell lines, and reagents

The strains used in the experiments (listed in Supplementary Table 2) were grown as described previously 9. The OKF6/TERT-2 oral epithelial cell line (provided by Jim Rheinwald, Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, Boston, MA) 29 was grown as described 9,29. OKF6/TERT-2 cells have been authenticated by RNA-Seq3, and have been tested for mycoplasma contamination. To determine the effects of the various inhibitors, the host cells were treated for 1 h prior to stimulation or infection with 2.5 μM dasatinib 30, 400 μM EphA2 antagonist, a 2,5-dimethylpyrrolyl benzoic acid derivative 15,31, 50 μM Stat3 inhibitor S31-201 32, 1μM gefitinib 16, 3 μg/ml dectin-1 mAb (R&D Systems) 33. In other experiments, the cells were stimulated with 50 μg/ml depleted zymosan (InvivoGen), 50 μg/ml mannan (Sigma), or 50 μg/ml laminarin (InvivoGen). To deplete the OKF6/TERT-2 cells of EphA2, they were transfected with random control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-37007), EphA2 siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-29304), or EphB2 siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-39949) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions as described previously16.

Confocal microscopy

The accumulation of EphA2 around C. albicans was visualized by confocal microscopy using a slight modification of our previously described methods 34. Oral epithelial cells were infected with 2 × 105 yeast organisms of a wild-type C. albicans strain expressing GFP. After 15, and 90 min, the cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde (wt/vol), blocked with 10% BSA (vol/vol), and incubated with antibodies against total EphA2 (Cell signaling; #6997) followed by an AlexaFluor 568-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody. The cells were then imaged by confocal microscopy, and the final images were generated by stacking optical sections along the z-axis. The binding of recombinant EphA2 (Biolegend) and Fc-hDectin-1a (InvivoGen) to fungal cells was visualized similarly.

Flow cytometry

Human buccal epithelial cells were isolated from healthy donors by gentle scraping of the oral cavity. The cells were suspended in DMEM + 10% FBS for 1 h and then washed with HBSS. Next, cells were incubated with a Dectin-1 antibody (R&D Systems; #MAB1859) followed by anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488 Ab. Control cells were incubated in a similar concentration of mouse IgG (Abcam, Inc.). The fluorescence of the cells was determined by flow cytometry, analyzing at least 10,000 cells per condition. The acquired events were plotted using forward scatter-Area (FSC-A) versus side scatter-Area (SSC-A) and the gate was set to exclude cellular debris. The remaining population was plotted using FL1-Height (AlexaFluor 488) and displayed as a histogram. The surface expression of dectin-1 on OKF6/TERT-2 cells was analyzed similarly.

Detection of protein phosphorylation

OKF6/TERT-2 cells in 24-well tissue culture plates were infected with 1 × 106 C. albicans for various times as described previously 16. Next, the cells were rinsed with cold HBSS containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors and removed from the plate with a cell scraper. After collected the cells by centrifugation, they were boiled in sample buffer. The lysates were separated by SDS/PAGE, and the phosphorylated proteins were detected by immunoblotting with phospho-specific antibodies, including anti-phospho-EphA2 (Cell signaling; #6347), anti-phospho-Stat3 (Cell signaling; #9134), anti-phospho-c-Fos (Cell signaling; #5348), anti-phospho-MEK1/2 (Cell signaling; #9154), anti-phospho-p65 (Cell signaling; # 3033). The blots were then stripped, and total protein levels and β-actin were detected by immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies against EphA2 (Cell signaling; #6997), EphB2 (Cell signaling; #83029), EphA4 (Santa Cruz; sc-365503), Stat3 (Cell signaling; # 12640), c-Fos (Cell signaling; # 4384), MEK1/2 (Cell signaling; # 9122), p65 (Cell signaling; # 8242), and β-actin (Cell signaling # 3700). The blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence and imaged with either a FluorChem 8900 (Alpha Innotech) or C400 (Azure biosystems) digital imager.

Stat3 ELISA

To quantify the phosphorylation of Stat3, OKF6/TERT-2 cells in 96-well tissue culture plates were treated with inhibitors for 1 h and then infected with 3 × 105 C. albicans cells for different time periods. Next the epithelial cells were permeabilized, and the phosphorylation of Stat3 was measured by an ELISA for phosph-Ser727 (LSBio) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of host cell endocytosis

The endocytosis of C. albicans by oral epithelial cells was quantified as described previously 9. OKF6/TERT-2 cells were grown to confluency on fibronectin-coated circular glass coverslips in 24-well tissue culture plates and then infected for 120 min with 2 × 105 yeast-phase C. albicans cells per well, after which they were fixed, stained, and mounted inverted on microscope slides. The coverslips were viewed with an epifluorescence microscope, and the number of endocytosed organisms per high-power field was determined, counting at least 100 organisms per coverslip. The effects of the inhibitors and EFNA1 (Acro Biosystems) on endocytosis were determined as described above. The inhibitors were added to the host cells 60 min before the fungal cells, and they remained in the medium for the entire incubation period.

Host cell damage assay

The extent of host cell damage caused by the C. albicans was measured using our standard 51Cr release assay 9,35. Briefly, OKF6/TERT-2 cells were grown to confluence in 96-well tissue culture plates, loaded with Na251CrO4 (MP Biomedicals) overnight, and then infected with 3 × 105 cells of the C. albicans. Uninfected epithelial cells were processed in parallel as a negative control. After an 8-h incubation, the amount of 51Cr that had been released into the medium and that remained associated with the cells was measured was determined by γ-counting. After correcting for well-to-well differences in the incorporation of 51Cr, the per cent specific release of 51Cr was calculated using the following formula: (experimental release-spontaneous release)/(total incorporation-spontaneous release). Experimental release was the amount of 51Cr released into the medium by cells infected with C. albicans. Spontaneous release was the amount of 51Cr released into the medium by uninfected host cells. Total incorporation was the sum of the amount of 51Cr released into the medium and remaining in the host cells. Each experiment was performed three times in triplicate.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated and real-time PCR was performed as previously described 36. The host cell RNA was extracted using the Ribopure Yeast Kit (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA levels of were measured by real-time PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 3. The relative transcript level of each gene was normalized to GAPDH by the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Measurement of hBD2 secretion

OKF6/TERT-2 cells in 24-well tissue culture plates were pre-treated with inhibitors and then infected with 1 × 106 C. albicans for 20 h. The supernatants were collected, clarified by centrifugation, and then stored at −80°C. At a later time, the levels of hBD2 were determined by ELISA (Peprotech), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytokine and chemokine measurements in vitro

Cytokine levels in culture supernatants were determine as previously described 37. Briefly OKF6/TERT-2 cells in a 96-well plate were infected with C. albicans at a multiplicity of infection of 5 or stimulated with a combination of 50 ng/ml IL-17A and 0.5 ng/ml TNF-α (both from Peprotech),. After 8 h of infection, the supernatant was collected, clarified by centrifugation and stored in aliquots at −80 °C. The concentration of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the medium was determined using the Luminex multipex assay (R&D Systems). Also, the concentration of IL-8 in the supernatants was determined by ELISA (R&D Systems). Each condition was tested in three independent experiments.

EphA2-binding ELISA

A polystyrene 96-well plate was coated with 50 μg carbohydrates (laminarin, zymosan, or mannan), 2 μg EFNA1 (positive control), or 50 μg BSA overnight at 20°C and then blocked with non-fat dry milk for 1 h. After the plate was extensively washed, 100 μg/mL recombinant EphA2 (Gln25-Asn534-6xHis; BioLegend) was added to each well and the plate was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The wells were rinsed and then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 1 μg/mL anti-His-HRP mAb, followed by rinsing and addition of the color reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (R&D Systems). After 5 min, stop solution was added and the optical density at 450 nm was determined.

In a different approach zymosan coated wells were incubated with recombinant EphA2, EGFR, Met 1-Ser 645-6xHis, or BSA (all at 100 μg/mL, ThermoFisher) and processed as described above.

Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis

EphA2−/− mice (backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background 26) were provided by A. Wayne Orr, LSU Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, LA. C57BL/6 controls were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. EphA2−/− and C57BL/6 control mice were cohoused for 1 week prior the experiments. 6 weeks old male EphA2−/− and age and sex-matched C57BL/6 mice were used in a mouse model of OPC 16,25. When immunocompromised EphA2−/− and C57BL/6 mice were used, triamcinolone (7 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously on days −1, 1, and 3. For inoculation, the animals were sedated, and a swab saturated with 106 C. albicans cells was placed sublingually for 75 min 25. Immunocompetent mice were inoculated similarly, except that the swab was saturated with 2 × 107 organisms 16. The immunocompromised and immunocompetent mice were sacrificed after 1 days and 4 day of infection, respectively. The mice were euthanized, and their tongue were harvested. The tongues were weighed, homogenized, and quantitatively cultured. To determine cytokine and chemokine protein concentrations during OPC the homogenates were prepared as previously described 38 and measured using a multiplex bead array assay (R&D Systems).

The effect of DAS on the severity of OPC was determined in triamcinolone (15 mg/kg) male BALB/C mice. BALB/C mice were randomized prior dasatinib or vehicle treatment. The mice were fed an oral solution of either dasatinib (10mg/kg/day) of the vehicle control (0.4% DMSO), twice a day, administered at 0.05 ml/mouse starting on day −1 relative to infection. At day 4 the tongue and attached tissues were harvested and divided by two. One-half was weighed, homogenized, and quantitatively cultured. The other one-half was snap frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT); 2 μm-thick sections were cut with a cryostat and fixed with cold acetone. To detect phosphorylation of Stat3, the cryosections were rehydrated in PBS and then blocked with 10 % BSA. Sections were stained with phospho-Stat3 Ab (Cell Signaling; #9134), Fc-Dectin-1 (InvivoGen), anti-Candida AlexaFluor 568, and stained with secondary antibody followed and imaged by confocal microscopy. To enable comparison of fluorescence intensity between slides, the same image acquisition settings were used for each experiment. For histopathology, additional cryosections were prepared and stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain.

In all of the mouse studies, the animals were randomly assigned to the different treatment groups. The researchers were not blinded to the experimental groups because the primary endpoint (oral fungal burden) was an objective measure of disease severity. Prior data indicated that the difference in oral fungal burden in the mouse model of OPC within each subject group was normally distributed with a standard deviation 0.2 log CFU/g tissue. If the true difference in the mean response of matched pairs is 0.5, the use of 4 pairs of mice would be sufficient to reject the null hypothesis with a probability (power) >0.9. The Type I error probability associated with this test of this null hypothesis is 0.05.

Statistics

At least three biological replicates were performed for all in vitro experiments unless otherwise indicated. Data were compared by Mann-Whitney, unpaired Student’s t test or Holm-Sidak method using GraphPad Prism (v. 6) software. P values < 0.05 were considered statistical significant.

Data availability

The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01DE022600 and R01AI124566 to S.G.F. and grant K99DE026856 to M.S. We are grateful to A. Wayne Orr and Alexandra C. Finney for providing the EphA2−/− mice. We thank Samuel W. French and Edward Vitocruz for histopathology, Ashraf S. Ibrahim, Michael R. Yeaman and Julian Naglik for providing strains, and members of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center for critical suggestions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest S.G.F. is a cofounder of and shareholder in NovaDigm Therapeutics, Inc., a company that is developing a vaccine against mucosal and invasive Candida infections.

Author contributions M.S., N.V.S., M.S.L. and S.G.F. designed the experiments. M.S. and N.V.S. performed the experiments. M.S., N.V.S., M.S.L. and S.G.F. analyzed the data. M.S. and S.G.F. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Underhill DM, Iliev ID. The mycobiota: interactions between commensal fungi and the host immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:405–416. doi: 10.1038/nri3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salvatori O, Puri S, Tati S, Edgerton M. Innate Immunity and Saliva in Candida albicans-mediated Oral Diseases. J Dent Res. 2016;95:365–371. doi: 10.1177/0022034515625222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conti Heather R, et al. IL-17 Receptor signaling in oral epithelial cells is critical for protection against oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyes DL, et al. A biphasic innate immune MAPK response discriminates between the yeast and hyphal forms of Candida albicans in epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyes DL, et al. Protection against epithelial damage during Candida albicans infection is mediated by PI3K/Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1816–1826. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park H, et al. Role of the fungal Ras-protein kinase A pathway in governing epithelial cell interactions during oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:499–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells JM, Rossi O, Meijerink M, van Baarlen P. Epithelial crosstalk at the microbiota-mucosal interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;1:4607–4614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000092107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu W, et al. EGFR and HER2 receptor kinase signaling mediate epithelial cell invasion by Candida albicans during oropharyngeal infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14194–14199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117676109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan QT, et al. Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swidergall M, Filler SG. Oropharyngeal Candidiasis: Fungal Invasion and Epithelial Cell Responses. PLoS Pathogens. 2017;13:e1006056. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitulescu ME, Adams RH. Eph/ephrin molecules--a hub for signaling and endocytosis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2480–2492. doi: 10.1101/gad.1973910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Underhill DM. Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. Embo J. 2005;24:1277–1286. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XD, et al. Identification of candidate predictive and surrogate molecular markers for dasatinib in prostate cancer: rationale for patient selection and efficacy monitoring. Genome Biol. 2007:8. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Hoecke A, et al. EPHA4 is a disease modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in animal models and in humans. Nat Med. 2012;18:1418–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solis NV, Swidergall M, Bruno VM, Gaffen SL, Filler SG. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor governs epithelial cell invasion during oropharyngeal candidiasis. MBio. 2017:8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00025-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen AB, et al. Activation of the EGFR gene target EphA2 inhibits epidermal growth factor-induced cancer cell motility. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:283–293. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naglik JR, Richardson JP, Moyes DL. Candida albicans pathogenicity and epithelial immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2014:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swidergall M, Ernst JF. Interplay between Candida albicans and the Antimicrobial Peptide Armory. Eukaryot Cell. 2014;13:950–957. doi: 10.1128/EC.00093-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conti HR, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li A, et al. IL-22 Up-Regulates beta-Defensin-2 Expression in Human Alveolar Epithelium via STAT3 but Not NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway. Inflammation. 2015;38:1191–1200. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-0083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiquee K, et al. Selective chemical probe inhibitor of Stat3, identified through structure-based virtual screening, induces antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7391–7396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609757104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Canavera SJ, Akira S, Underhill DM. Collaborative Induction of Inflammatory Responses by Dectin-1 and Toll-like Receptor 2. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197:1107–1117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferwerda G, Meyer-Wentrup F, Kullberg BJ, Netea MG, Adema GJ. Dectin-1 synergizes with TLR2 and TLR4 for cytokine production in human primary monocytes and macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2058–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solis NV, Filler SG. Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:637–642. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finney AC, et al. EphA2 Expression Regulates Inflammation and Fibroproliferative Remodeling in Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2017;9:026644. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goupil M, et al. Defective IL-17- and IL-22-dependent mucosal host response to Candida albicans determines susceptibility to oral candidiasis in mice expressing the HIV-1 transgene. BMC Immunol. 2014;15:49. doi: 10.1186/s12865-014-0049-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trautwein-Weidner K, Gladiator A, Nur S, Diethelm P, LeibundGut-Landmann S. IL-17-mediated antifungal defense in the oral mucosa is independent of neutrophils. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:221–231. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickson MA, et al. Human keratinocytes that express hTERT and also bypass a p16(INK4a)-enforced mechanism that limits life span become immortal yet retain normal growth and differentiation characteristics. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1436–1447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1436-1447.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subbarayal P, et al. EphrinA2 receptor (EphA2) is an invasion and intracellular signaling receptor for Chlamydia trachomatis. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004846. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noberini R, et al. Small molecules can selectively inhibit ephrin binding to the EphA4 and EphA2 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29461–29472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804103200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Purvis HA, Anderson AE, Young DA, Isaacs JD, Hilkens CM. A negative feedback loop mediated by STAT3 limits human Th17 responses. J Immunol. 2014;193:1142–1150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertuzzi M, et al. The pH-responsive PacC transcription factor of Aspergillus fumigatus governs epithelial entry and tissue invasion during pulmonary aspergillosis. PLoS Pathog. 2014:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu Y, et al. Investigation of the Function of Candida albicans Als3 by Heterologous Expression in Candida glabrata. Infect Immun. 2013;81:2528–2535. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00013-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ariyachet C, et al. SR-like RNA-binding protein Slr1 affects Candida albicans filamentation and virulence. Infect Immun. 2013;81:1267–1276. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00864-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phan QT, Filler SG. Endothelial cell stimulation by Candida albicans. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;470:313–326. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-204-5_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus CalA binds to integrin alpha5beta1 and mediates host cell invasion. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:211. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Break TJ, et al. CX(3)CR1 Is Dispensable for Control of Mucosal Candida albicans Infections in Mice and Humans. Infection and Immunity. 2015;83:958–965. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02604-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.