Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to determine whether the DiaRem, a score that predicts type 2 diabetes (T2D) remission following roux-en-y gastric bariatric surgery (RYGB), also predicts remission following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in white and Hispanic patients.

Summary Background Data

While bariatric surgery is highly effective in reversing insulin resistance, there are patients for whom surgery will not lead to remission. To date, there is no score for predicting remission following LAGB or LSG surgery. Additionally, there is little known about how to predict whether Hispanic patients will experience remission.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of white and Hispanic patients with T2D who received bariatric surgery. There were 361 white and 130 Hispanic patients among whom 328 had RYGB surgery, 107 had LSG surgery, and 56 had LAGB surgery. We used age, diabetes treatment, and hemoglobin A1c to calculate DiaRem scores. Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the association between DiaRem scores and remission. Area under the receiver operant curve (AUC) was used to assess the ability of the DiaRem to discriminate between patients who did and did not remit.

Results

The DiaRem was associated with partial remission in all surgeries types for white and Hispanic patients (Mann-Whitney, p<0.001.) The DiaRem had moderate to high discriminant ability (AUC > 0.70) for all surgical and racial/ethnic groups.

Conclusions

The DiaRem distinguishes between patients likely and unlikely to experience remission, informing expectations of patients making T2D treatment decisions.

INTRODUCTION

Bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective treatment in reversing insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [1–3]. Over the past decade, the surgical treatment options for patients with T2D have grown and treatment preferences have changed. There has been a shift in practice pattern away from laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) and roux-en-y gastric bypass (RYGB) to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) [4]. The literature reports that remission rates, as well as predictors of remission, vary across surgery types [5–7]. Patients and their doctors are challenged to synthesize these data to determine whether the risks of a specific type of bariatric surgery for a patient outweigh the benefits. The ability to distinguish between patients for whom surgery will and will not induce remission can help to facilitate a more tailored approach to T2D treatment decisions and inform guidelines determining patient eligibility for surgery. To date, there is no method for predicting remission outcomes following LAGB and LSG surgery.

While whites are more likely to undergo bariatric surgery, surgeries have been increasing in other races [8]. The impact of bariatric surgery on metabolic syndrome and excess weight loss has been shown to differ by race/ethnicity [9–11]. However, little is known about how race and ethnicity impacts remission rates [9–11.] As a consequence of this knowledge gap, there is little guidance for non-white patients considering surgical treatment regarding the likelihood of remission following surgery.

The DiaRem score is a validated score, derived from data readily available in the medical record that has been shown to predict the likelihood a patient will experience remission following surgery RYGB [5, 12–14]. Despite its predictive ability, the DiaRem is based on data from a largely non-Hispanic white population sample who had RYGB surgery, raising questions about its applicability to other ethnic groups and other surgery types. We used longitudinal medical record data from two distinct health care systems to determine whether the DiaRem score can predict the likelihood of remission following LAGB and LSG and whether it predicts remission in a Hispanic patient population.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who received bariatric surgery in one of two health systems: Geisinger Health System or NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue. Geisinger is an integrated health system located in Pennsylvania that services patients across 45 predominately rural counties in Pennsylvania. Geisinger patients who had RYGB, LSG, or LAGB surgery between 2002 and 2014 were included in the study, unless they were part of the sample used for the original development and validation of the DiaRem for RYBG, as previously described [5]. Bellevue is located in New York City and 1 of 11 hospitals in the NYC Health and Hospitals system. Bellevue patients who received surgery between 2008 and 2014 were included in the study. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Geisinger Health System and New York University Medical Center/Bellevue Hospital.

Patients from both health systems had to meet the following additional eligibility criteria: T2D prior to surgery; body mass index (BMI) > 35kg/m2; hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and BMI values in the medical record before and after surgery; at least 12-months of post-surgical care recorded in the medical record; and diabetes medication data available before and after surgery. We defined T2D according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines: fasting blood glucose concentration of more than 7.0% (53 mmol/mol; average blood glucose of 154.41 mg/dL) or HbA1c concentration of more than 6.5% (48 mmol/mol; average blood glucose of 140.04 mg/dL) [15]. Additional confirmation was obtained by examination of the electronic health record for the International Classification of Diseases (9th revision) code for T2D.

DiaRem scores were calculated for all eligible patients. The scoring system is described in detail elsewhere [5]. Briefly, the DiaRem is a weighted score based on the sum of an age score (<40 = 0, 40–49 = 1, 50–59 = 2, 60+ = 3), insulin dependence (no = 0, yes = 10), diabetes medication use (additional 3 points if on sulfonylureas and insulin sensitizing agent other than metformin), and HbA1c (<6.5% = 0, 6.5–6.9% = 2, 7.0–8.9% = 4, 9.0%+ = 6), ranging from 0 to 22 points. Patients were stratified into groups by DiaRem score (0–2, 3–7, 8–12, 13–17, and 18–22.)

Remission of T2D was defined according to the ADA’s criteria for partial remission (16). Patients were classified as remitted if they had an HbA1c concentration of less than 6.5% (48 mmol/mol; average blood glucose of 140.04 mg/dL), fasting blood glucose concentrations of less than 7.0% (53 mmol/mol; average blood glucose of 154.41 mg/dL) and no use of antidiabetic drugs for at least 12 months. All information was extracted from the electronic health record systems of the two health care settings.

We used two-sample t-tests, chi-square tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests to compare patient populations across surgical type, ethnicity, and location of surgery (Geisinger vs. Bellevue.) The populations were compared on sex (male versus female), age at surgery, race (white, Hispanic, Black), pre-surgical HbA1c and body mass index (BMI) values, pre-surgical diabetes medication use (insulin, metformin, other insulin-sensitizing agent, sulfonylureas, other diabetes medications), and DiaRem score.

To determine whether DiaRem score was associated with the likelihood of partial remission we used the Mann-Whitney U sum test. Next, we estimated the area under the receiver operant curve (AUC) and bootstrap 95% confidence intervals to assess the ability of the DiaRem to discriminate between remitted and non-remitted type 2 diabetes cases. The AUC can range from 1.0 (perfect discrimination) to 0.5 (discrimination equivalent to a coin toss.) We estimated AUC using the c-statistic, generated by logistic regression. The Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves were evaluated to identify the optimal DiaRem score that maximized sensitivity and specificity. Analyses were conducted on all surgery patients, by surgery type, by race/ethnicity, and by surgery/type ethnicity.

RESULTS

There were 372 Geisinger patients and 148 Bellevue patients who met the study eligibility criteria. Among the eligible patients, 340 had RYGB surgery, 119 had LSG surgery, and 61 had LAGB surgery. (Table 1) RYGB was more commonly performed at Geisinger, accounting for 88% of the RYGB surgeries, while 67% of the LSG surgeries were performed at Bellevue. At least 90% of patients in each of the surgery groups were white or Hispanic. Therefore, analysis was confined to white (n=361) and Hispanic (n=130) patients. Among the white patients, 99% were treated at Geisinger. Bellevue treated 97% of the Hispanic patients.

Table 1.

Profile of bariatric patients with diabetes included in the study cohort by race/ethnicity (limited to white and Hispanic) and by surgery type

| White N=361 |

Hispanic N=130 |

p-value | RYGB N=340 |

LSG N=119 |

LAGB N=61 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 49.9 (10.8) | 46.9 (10.1) | 0.0066a | 48.9 (10.6) | 46.7 (10.1) | 53.0 (11.4) | 0.0008a |

| Sex, % (n) | 75% (255) | 78% (93) | 79% (48) | 0.695b | |||

| Female | 72% (259) | 85% (111) | 0.0020b | ||||

| Male | 28% (102) | 15% (19) | 25% (85) | 22% (26) | 21% (13) | ||

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) White |

100% (361) | – | NA | 86% (291) | 30% (36) | 56% (34) | <0.0001b |

| Hispanic | – | 100% (130) | 11% (37) | 60% (71) | 36% (22) | ||

| Black, | 2% (8) | 9% (11) | 8% (5) | ||||

| Other/unknown | 1% (4) | 1% (1) | 0% (0) | ||||

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 48.7 (8.5) | 44.7 (8.0) | <0.0001a | 48.6 (9.0) | 47.5 (8.9) | 45.9 (6.7) | 0.071a |

| Diabetes meds, % (n) Insulin | 34% (122) | 32% (42) | 0.758b | 36% (122) | 26% (31) | 36% (22) | 0.136b |

| Metformin | 76% (276) | 76% (99) | 0.945b | 77% (263) | 74% (88) | 69% (42) | 0.325b |

| Other ISA | 14% (52) | 13% (17) | 0.709b | 15% (50) | 10% (12) | 15% (9) | 0.434b |

| Sulfonylureas | 30% (109) | 20% (26) | 0.026b | 27% (91) | 24% (28) | 33% (20) | 0.414b |

| Other diabetes meds | 17% (61) | 29% (38) | 0.0027b | 19% (63) | 28% (33) | 23% (14) | 0.100b |

| Baseline HbA1c, mean (SD) | 7.0 (1.2) | 7.9 (1.8) | <0.0001a | 7.2 (1.4) | 7.5 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.8) | 0.085a |

| DiaRem score, mean (SD) | 7.5 (6.2) | 7.9 (6.4) | 0.521a | 7.8 (6.7) | 7.0 (5.5) | 8.2 (6.7) | 0.346a |

| DiaRem group, % (n) | |||||||

| 0–2 | 27% (99) | 21% (27) | 0.230c | 28% (95) | 22% (26) | 23% (14) | 0.595c |

| 3–7 | 35% (128) | 42% (54) | 32% (110) | 46% (55) | 38% (23) | ||

| 8–12 | 6% (22) | 8% (10) | 6% (21) | 9% (11) | 7% (4) | ||

| 13–17 | 27% (96) | 19% (25) | 27% (93) | 19% (23) | 21% (13) | ||

| 18–22 | 4% (16) | 11% (14) | 6% (21) | 3% (4) | 11% (7) | ||

| Surgery type, % (n) RYGB |

81% (291) | 28% (37) | <0.0001b | 100% (340) | – | – | NA |

| LSG | 10% (36) | 55% (71) | – | 100% (n=119) | – | ||

| LAGB | 9% (34) | 17% (22) | – | – | 100% (61) | ||

| Institution, % (n) GHS |

99% (356) | 3% (4) | <0.0001b | 88% (299) | 33% (39) | 56% (34) | <0.0001b |

| Bellevue | 1% (5) | 97% (126) | 12% (41) | 67% (80) | 44% (27) |

Two-sample t-test

Chi-square test

Wilcoxon Rank Sum test

We compared patients across surgery types on diabetes control and treatment status at time of surgery. The average HbA1c ranged from 7.2% (55 mmol/L) to 7.5% (58 mmol/L) across surgery types; insulin use ranged from 26% of patients to 36%; and metformin use ranged from 69% to 77% of patients (all p>0.05). Surgery groups differed by age, ranging from an average of 46.7 years for LSG patients to 53 years for LAGB patients (p=0.0008). Surgery groups also differed by race, with surgeries in white patients accounting for 86% of RYGB surgeries, 56% of LAGB surgeries, and 30% of LSG patients (P<0.0001). The race distributions mirrored the distribution of the location of surgery, Geisinger or Bellevue, across surgery types.

We compared white patients and Hispanic patients on the components of the DiaRem at the time of surgery: age, medication use, insulin use, and HbA1c. On average, patients were 46 (Hispanic) and 50 (White) years of age (p=0.007.) White and Hispanic patients had similar treatment profiles at the time of surgery. Hispanic patients had a higher average HbA1c (7.9%, 63 mmol/L) than white patients (7.0, 53 mmol/L), (p< 0.0001.) Despite differences in age and HbA1c, the distribution of DiaRem scores across ethnic groups were not significantly different.

DiaRem performance in RYGB, LSG, and LAGB surgery

The DiaRem score was associated with the proportion of patients achieving partial remission within 2 years of surgery in RYBG, LSG, and LAGB surgeries (Mann-Whitney, p<0.001.) (Figure 1) Across surgeries, patients with the lowest DiaRem scores were more likely to remit. Among patients with a DiaRem score of 0–2, 84% of RYGB patients, 73% of LSG patients, and 57% of LAGB patients experienced remission, compared to 10% of RYGB patients and 0% of LSG and LAGB patients with a DiaRem score greater than 17. Discriminant ability of the DiaRem was moderate to high (AUC, bootstrap 95% CI) for all surgery types. (Table 2) The AUC was higher for RYGB (0.858, 0.818–0.898), and LAGB (0.880, 0.775–0.962), than for LSG (0.707, 0.604–0.807). The AUC confidence interval for LAGB did not overlap the confidence interval for LSG, indicating that the DiaRem performs better for LAGB than LSG.

Figure 1.

Percent with early diabetes remission by surgery type (Wilcoxon p<0.001 for each surgery type)

Table 2.

Area under the curve and bootstrap 95% confidence intervals

| Group | N | Optimal cut-off point* | AUC | Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DiaRem | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| All subjects | 520 | 8 | 0.62 | 0.91 | 0.825 | [0.785, 0.859] |

| White | 361 | 8 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 0.839 | [0.798, 0.879] |

| Hispanic | 130 | 7 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.790 | [0.710, 0.861] |

| RYGB | 340 | 8 | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.858 | [0.818, 0.898] |

| LSG | 119 | 7 | 0.56 | 0.89 | 0.707 | [0.604, 0.807] |

| LAGB | 61 | 4 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.880 | [0.775, 0.962] |

| White and RYGB | 291 | 8 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.860 | [0.814, 0.903] |

| White and LSG | 36 | 8 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.714 | [0.523, 0.876] |

| White and LAGB | 34 | 4 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.833 | [0.673, 0.956] |

| Hispanic and RYGB | 37 | 15 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 0.863 | [0.722, 0.961] |

| Hispanic and LSB | 71 | 7 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.713 | [0.582, 0.830] |

| Hispanic and LAGB | 22 | 5 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.947 | [0.833, 1.000] |

Optimal cut-off point was defined as the DiaRem score that maximizes sensitivity and specificity

The optimal cut-off point, the DuraRem score that maximized sensitivity and specificity, differed across surgery types. RYGB had an optimal cut-off point of 8, LSG was 7, and LAGB was 4. Specificity of these cut-off points was high in all surgery types, while sensitivity ranged from a low of 0.56 for LSG to a high of 0.80 in LAGB.

DiaRem performance in white and Hispanic patients

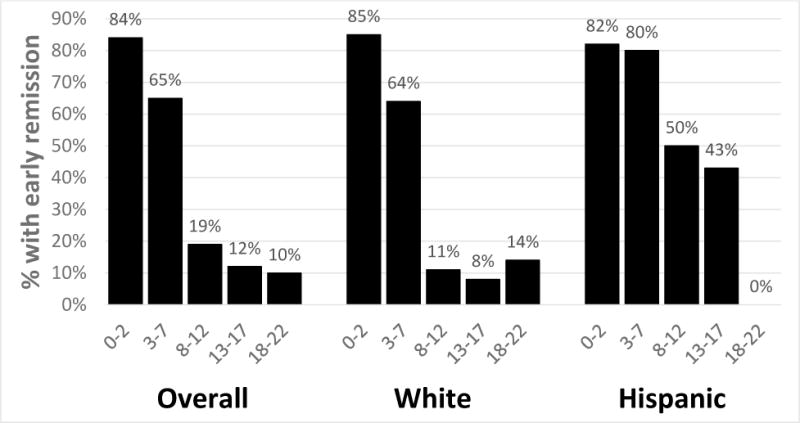

The DiaRem score predicted early remission in both white and Hispanic patients (Mann-Whitney, p<0.001.) (Figure 2) Lower DiaRem scores were associated with greater likelihood of remission. Among patients with DiaRem scores of 0–2, 82% of white patients and 74% of Hispanic patients remitted, compared to 13% of white and 0% of Hispanic patients with scores of 18 or greater. The DiaRem had high discriminant ability in both white (0.839, 0.798–0.879) and Hispanic patients (0.790, 0.710–0.861). The optimal cut-off points were similar as well, 7 for white and 8 for Hispanic patients. In both groups these cut-off points had high specificity and moderate sensitivity.

Figure 2.

Percent with early diabetes remission by ethnicity (Wilcoxon p<0.001 for each surgery type)

DiaRem performance in three surgery types in white and Hispanic patients

For both white and Hispanic patients, the DiaRem predicted remission for each surgery type (Mann-Whitney p=0.05). (Figures 3a–3c) For each surgery type in white and Hispanic patients, the largest proportion of patients to achieve remission was in patients with a DiaRem score of 0–2, with a steep drop-off in remission for scores above 7. Among white and Hispanic patients who had LAGB surgery, no patients with a DiaRem score between 8 and 22 remitted. Consistent with these findings the DiaRem had moderate to high discriminant ability for each surgery type in the two race/ethnic groups. In Hispanic patients, the highest AUC was for LAGB (0.947, 0.833–1.00). The AUC confidence interval for LAGB did not overlap the confidence interval for LSG (0.713, 0.582–0.830) in the Hispanic patient population, indicating that the DiaRem performs better for LAGB than LSB in Hispanic patients. The optimal cut-off point was highest (15) in Hispanic patients who had RYGB, while the lowest cut-off points were in white (4) and Hispanic patients (5) who had LAGB.

Figure 3a.

Percent with early diabetes remission by race/ethnicity for RYGB surgeries (Wilcoxon p<0.05 for each group)

Figure 3c.

Percent with early diabetes remission by race/ethnicity for LAGB surgeries (Wilcoxon p<0.05 for each group)

CONCLUSION

The DiaRem score predicts the likelihood of T2D remission for RYGB, LAGB, and LSG surgery in white and Hispanic patients. This is the first study to evaluate a score for predicting T2D remission in three surgery types across multiple race/ethnic groups. While bariatric surgery has been shown to be highly effective in reversing insulin resistance, there are a subset of patients for whom surgery is unlikely to result in T2D remission [17]. The DiaRem distinguishes between these patients using data readily available in the medical record, making it a useful and accessible tool for facilitating more informed treatment decisions for patients and physicians considering surgery to treat T2D.

Prior to this study, no tools have been evaluated to predict remission in LSG and LABG surgery. The shift in popularity from RYBG to other surgery types has increased the demand for such a tool [4]. While the DiaRem has consistently proven to predict remission after RYBG surgery, it was unknown whether the DiaRem would predict remission following other types of surgery. Remission rates in the first year after surgery differ across surgery types, with higher rates for RYGB and LSG than LABG [18]. Panunzi and colleagues [6] recently reported that predictors of T2D remission also differs by surgery type. We found that the DiaRem better differentiates remitted and unremitted cases for LABG than LSG in Hispanic patients, but not in white patients. We also observed that the optimal cut-off point for predicting remission varies by surgery type. However, the DiaRem performs well across all three surgery types in both racial/ethnic groups, with high specificity and moderate sensitivity.

Our findings support the use of the DiaRem among both white and Hispanic patients to predict their chances of experiencing remission after surgery. To date, the DiaRem has been validated in primarily non-Hispanic white populations, with the exception of a recent study of 64 patients undergoing RYGB surgery in Brazil [13]. However, the DiaRem had not been validated for other surgery types in a Hispanic population. The risk of T2D among Hispanic adults is 66% higher than it is for non-Hispanic white adults and the incidence and prevalence continues to grow, but the outcomes of bariatric surgery in this population remain poorly understood [19–20]. Our findings fill some of this gap, informing the expectations of the growing number of Hispanic patients and their doctors seeking T2D treatment options.

The DiaRem is calculated using four variables readily available in most medical records: age, HbA1c, insulin use, and diabetes medications. It is based on a simple algorithm that can be used by patients at home or during clinic visits in real-time. The DiaRem variables were identified by Still and colleagues [6] from among 259 clinical variables as the most predictive of remission after RYGB surgery. Other studies have identified alternative predictors of T2D remission, including duration of diabetes, fasting glycemia measures, and C-peptide levels [6,21,22]. Differences across studies are, in part, due to differences as to what variables were evaluated. To our knowledge, the DiaRem is the first score to be evaluated across three surgery types in two racial/ethnic groups and was shown to perform well in all groups.

The DiaRem score notably does not include body mass index (BMI), one of the primary criteria used to determine surgery eligibility [23]. BMI was excluded based on analysis used for the development of the DiaRem that found that BMI was not predictive of remission, a finding that has been since reported by others [6]. Our study adds to the mounting evidence that there are factors, in addition to BMI, that should be considered when determining eligibility for bariatric surgery to ensure that patients likely to benefit from surgery are not denied this potentially life-saving treatment option [1,5,6,24].

The frequently touted effectiveness of bariatric surgery on T2D over other treatment strategies does not reflect the reality that for some patients there is almost no chance of experiencing remission [17]. This observation should not detract from the other potential benefits of surgery (e.g., weight loss, cardiovascular benefits), as these benefits can occur in the absence of diabetes remission. The DiaRem is limited to predicting remission, but has not been assessed for its ability to predict these other important surgical outcomes. However, for patients pursuing surgery for the purposes of treating their T2D, the DiaRem gives patients more than an average remission rate; the DiaRem provides a tailored prediction of remission, based on the patient’s age and diabetes severity and treatment profile.

This study has some limitations. First, this was an observational study using retrospective data from two institutions. The institution where the surgery occurred was highly correlated with race/ethnicity and surgery type, making it possible to separate race/ethnicity, surgery type, and institutional effects. A study of institutions that have greater diversity in race and surgery type would facilitate the analysis necessary to parse race/ethnic, surgery type, and institutional effects on DiaRem performance. A second limitation is incomplete data on the different heritage groups within the Hispanic population. Prevalence of T2D differs across some Hispanic populations [25]. It is not known whether response to T2D differs as well. It was not possible, given our limited sample size and degree of missing data on Hispanic heritage, to evaluate how the DiaRem performs in these populations. Finally, this study evaluated the performance of the DiaRem for short-term remission of T2D. The DiaRem has been shown to predict prolonged T2D remission, remission lasting at least 5 years, for RYGB [27]. Future research should determine the degree to which the DiaRem predicts prolonged remission for other surgery types and ethnic groups.

The DiaRem leverages four data elements readily available in the medical record to predict whether a patient will experience remission following bariatric surgery. The DiaRem informs targeted treatment decisions for white and Hispanic patients considering the range of surgical treatments available to treat their T2D. Moreover the DiaRem identifies patients most likely to benefit from surgery, information highly relevant to the ongoing debate regarding the eligibility requirements for bariatric surgery.

Figure 3b.

Percent with early diabetes remission by race/ethnicity for LSG surgeries (Wilcoxon p<0.05 for each group)

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by The Mid-Atlantic Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NORC) under NIH award number P30DK072488.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: GW, DH, MP, CS, PB, AH reported no conflict of interest. TM reported funding from The Mid-Atlantic Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NORC) under NIH award number P30DK072488.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained for all individual participants included in the study.

Human rights: The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Geisinger Health System and New York University Medical Center/Bellevue Hospital and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Authors contributed the following in the development of this manuscript: AH, GW, TM, MP were involved in the conception and study design. GW conducted data analysis. AH wrote the manuscript. All authors (GW, DH, MP, CS, TM, PB, AH) were involved in the interpretation of the data, manuscript revisions and approval of the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1577–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200111. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200111 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parikh M, Chung M, Sheth S, et al. Randomized pilot trial of bariatric surgery versus intensive medical weight management on diabetes remission in type 2 diabetic patients who do NOT meet NIH criteria for surgery and the role of soluble RAGE as a novel biomarker of success. Ann Surg. 2014;260(4):617–624. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000919. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000919 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1567–1576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200225 [doi]] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham A, Ikramuddin S, Jahansouz C, Arafat F, Hevelone N, Leslie D. Trends in bariatric surgery: Procedure selection, revisional surgeries, and readmissions. Obesity Surgery. 2016;26(7):1371–1377. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1974-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Still CD, Wood GC, Benotti P, Petrick AT, et al. Preoperative prediction of type 2 diabetes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2014;2(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panunzi S, Carlsson L, De Gaetano A, Peltonen M, Rice T, Sjosrom L, et al. Determinantas of diabetes remission and glycemic control after bariatric surgery. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(1):166–174. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoatoum IJ, Blackstone R, Hunter TD, Francis DM, Steinbuch M, Harris JB, Kaplan LM. Clinical factors associated with remission of obesity-related comorbidities after bariatric surgery. JAMA Surgery. 2016;151(2):130–137. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worni M, Guller U, Maciejewksi JL, Curtis LH, Ganhi M, Pietrobon R, Jacobs DO, Ostye T. Racial differences among patients undergoing laparascopic gastric bypass surgery: A population-based trend analysis from 2002 to 2008. Obesity Surgery. 2013;23:226–233. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0832-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman KJ, Brookey J. Gender and racial/ethnic background predict weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass independent of health and lifestyle behaviors. Obesity Surgery. 2014;24:1729–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman KJ, Huang Y, Koebnick C, Reynolds K, Xiang AH, Black MH, Alskaf S. Metabolic syndrome is less likely to resolve in Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks after surgery. Annals of Surgery. 2014;259(2):279–285. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Admiraal WM, Celik F, Gerdes VE, Dallal RM, Hoekstra JB, Holleman F. Ethnic differences in weight and diabetes remission after bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1951–1958. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Kashyap SR, Kirwan JP, Schaer PR. DiaRem score: External validation. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2014;2(1):12–13. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70202-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampaio-Neto J, Nassif LS, Branco-Filho AJ, Bolfarini LA, Loro LS, Souza MP, Bianco T. External validation of the DiaRem score as remission predictor of diabetes mellitus type 2 in obese patients undergoing roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cirugia Digestiva. 2015;28(Supple 1) doi: 10.1590/S0102-6720201500S100007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotillard A, Pouitou C, Duchateau-Nguyen D, Aron-Wisnewky J, Bouillot J, Schindler T, Clement K. Type 2 diabetes remission after gastric bypass: What is the best prediction tool for clinicians? Obesity Surgery. 2015;25:1128–1132. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2012. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2133–2135. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buse JB, Caprio S, Cefalu WT, Ceriello A, St Del Prato, Inzucchi SE, et al. How do we define cure of diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):2133–2135. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dicker D, Yahalom R, Comanshter DS, Vinker S. Long-term outcomes of three types of bariatric surgery on obesity and type 2 diabetes control and remission. Obesity Surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-2025-8. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geiss LS, Wang J, Cheng YJ, Thompson TJ, Barker L, Li Y, Albright AL, Gregg EW. Prevalence and incidence trends for diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 20 to 79, United States, 1980–2012. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1218–1226. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon JB, Chuang LM, Chong K, et al. Predicting the glycemic response to gastric bypass surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2013;36:20–26. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackstone R, Bunt JC, Cortés MC, Sugerman HJ. Type 2 diabetes after gastric bypass: remission in five models using HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and medication status. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2012;8:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon JB, Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Rubino F. International Diabetes Federation Taskforce on Epidemiology and Prevention. Bariatric Surgery: an IDF statement for obese type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Medicine. 2011;28:628–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maggard-Gibbons M, Maglione M, Livhits M, et al. Bariatric surgery for weight loss and glycemic control in nonmorbidly obese adults with diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2013;309:2250–2261. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneiderman N, Liabre M, Cowie CC, Bomhart J, Carnethon M, Gallo LC. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from diverse backgrounds: The Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2233–2239. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood GC, Mirshahi T, Still CD, Hirsch AG. We don’t have to wait for precision medicine to cure type 2 diabetes. JAMA Surgery [Google Scholar]