Abstract

Objective

Family caregiver involvement may improve patient and family outcomes in the intensive care unit. This study describes critical care nurses’ approaches to involving family caregivers in direct patient care.

Research Methodology/Design

This is a qualitative content analysis of text captured through an electronic survey.

Setting

A convenience sample of 374 critical care nurses in the United States who were subscribers to one of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses social media sites or electronic newsletters.

Main Outcome Measure

Critical care nurses’ responses to five open-ended questions about their approaches to family involvement in direct patient care.

Findings

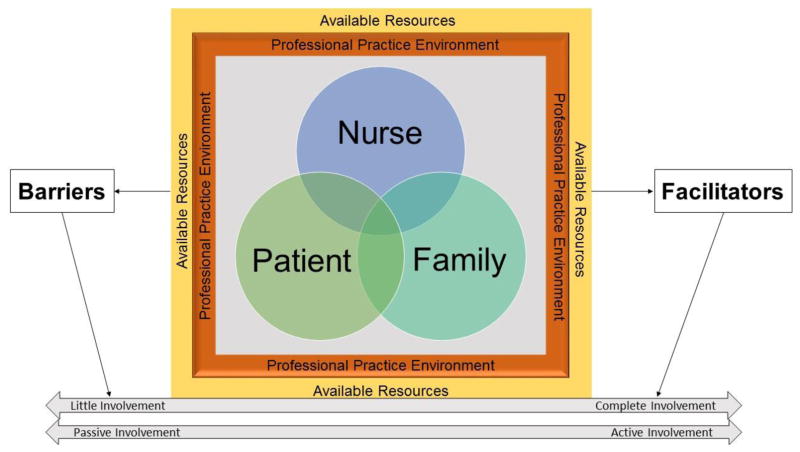

Nurse, patient, and family caregiver factors intersected in the context of the professional practice environment and the available resources for family care. Two main themes were identified: “Involving Family Caregivers in Patient Care in the ICU Requires Careful Assessment” and “There are Barriers and Facilitators to Caregiver Involvement in Patient Care in the ICU.”

Conclusion

Patient care demands, the professional practice environment, and a lack of resources for families hindered nursing family caregiver involvement. Greater attention to these barriers as they relate to family caregiver involvement and clinical outcomes should be a priority in future research.

Keywords: caregiver, critical care, engagement, ICU, involvement, family, patient care

INTRODUCTION

Each year, 5.7 million Americans are admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) (Society of Critical Care Medicine, 2017). Critical illness is physically and psychologically distressing for patients and their families. Family members of critically ill patients are routinely expected to assume caregiving roles, often without adequate preparation, which can negatively affect their health and well-being (Cameron et al., 2006, 2016; Choi et al., 2011; Douglas & Daly, 2003; Fry & Warren, 2007; Hickman & Douglas, 2010; Johnson et al., 2001; Van Pelt et al., 2007). In fact, half of family members of patients receiving care in the ICU report symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Anderson et al., 2008). The intense negative psychological impact of a patient’s critical illness may be further exacerbated when family members are not involved as a component of care or if they do not receive sufficient emotional support, information, or communication from critical care providers (Anderson et al., 2008; Tyrie & Mosenthal, 2012).

BACKGROUND

Recent policies and practice guidelines supported by clinical research recommend care delivery guided by a patient and family engagement (PFE) model of care (Brown et al., 2015). The PFE model of care constitutes an active partnership between healthcare providers, patients, and families (Brown et al., 2015). PFE has been successfully incorporated in the ICU through passive care interventions such as open visitation, family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and invasive procedures, and shared decision making between caregivers and healthcare staff (Brown et al., 2015; Davidson et al., 2007, 2017; Olding et al., 2015). However, implementation of PFE by involving family caregivers in direct patient care has the potential to enhance the patient and family experience with critical illness as well as improve safety, quality, and delivery of care (Brown et al., 2015; Davidson et al., 2007, 2017; Mitchell et al., 2009; Olding et al., 2015). Active family involvement in patient care in the critical care setting has received little attention in research and policy, possibly due to opposing ideologies about family involvement in the ICU and a small body of literature examining the practice (Al-Mutair et al., 2013a, 2013b; El-Masri & Fox-Wasylyshyn, 2007; Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2010; Hammond, 1995; Olding et al., 2015).

Critical care nurses have an opportunity to establish meaningful relationships with patients and their families and are well positioned to promote active family involvement. In one study, as nurses’ comfort level with family care increased, family-focused nursing interventions increased as well (El-Masri & Fox-Wasylyshyn, 2007). This finding indicates an opportunity to enhance PFE through nurse engagement and training. Yet, some evidence suggests that critical care nurses have varying opinions about the family’s role in the ICU, particularly when involving family in direct patient care (El-Masri & Fox-Wasylyshyn, 2007; Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2010; Hetland et al., 2017; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centred Care, 2016; McConnell & Moroney, 2015). A significant correlation between the barriers related to the delivery of family-centred care and nurse attitudes was reported in a prior study (Ganz & Yoffe, 2012), and ambiguity among nurses about enabling family involvement with patient care has been documented in recent reviews (Liput et al., 2016; Olding et al., 2015). Potential threats to patient and family safety is a theme across the limited body of literature addressing family involvement in care (Hammond, 1995; Liput et al., 2016; McConnell & Moroney, 2015). Thus, without nurse support of the PFE practice model, it is difficult to further explore and test the benefits of this approach to care.

Although there are many documented family benefits to family involvement in exploratory studies, such as: 1) a greater sense of family-centred care (Mitchell et al., 2009); 2) feeling connected to the goal of improving the health of the critically ill family member (Hammond, 1995); 3) a reduction of anxiety (Al-Mutair et al., 2013a); and 4) higher satisfaction for family members (Al-Mutair et al., 2013a), there is a paucity of research examining the impact of family involvement on patient and family outcomes (Al-Mutair et al, 2013b; Brown et al., 2015; Hammond, 1995; Liput et al., 2016; McConnell & Moroney, 2015; Olding et al, 2015). In the 2017 Guidelines for Family-Centred Care in the ICU (Davidson et al., 2017), the recommendation to teach family members about how to assist in care is only directed at the neonatal population, as the majority of interventional studies have been conducted in this setting. Although some studies have examined outcomes of family involvement in care (Liput et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2009, 2016), the majority of the literature is descriptive and focused on attitudes of nurses regarding the practice of family involvement (Al-Mutair et al., 2013b; Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2010; Hammond, 1995). There is a gap in the literature addressing how critical care nurses currently practise PFE, and the ways they perform this component of patient and family care in the ICU environment.

A comprehensive analysis of critical care nurses’ approaches to family involvement in patient care will help critical care nurse leaders understand how to build collaborative partnerships between patients, families, and critical care nurses (Hetland et al., 2017). Understanding how nurses involve families in direct patient care can guide future studies that aim to test PFE interventions. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore nurses’ approaches to incorporating family caregivers into patient care in the ICU and identify opportunities to enhance active family involvement in the critical care environment.

METHODS

Design

This study is a qualitative content analysis of text obtained from a mixed-methods survey (Hetland et al., 2017) that explored critical care nurses’ approaches to family involvement in the care of a critically ill patient. The mixed-methods survey consisted of a 15-item quantitative measure titled, “Questionnaire on Factors that Influence Family Engagement (QFIFE)” and five open-ended qualitative questions. This paper reports only the qualitative data from the five open-ended questions.

Sample

A convenience sampling methodology was used to recruit critical care nurses who were subscribers to one of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) social media sites or electronic newsletters. At the time of participant recruitment, AACN’s total membership was 108,422. Participants were critical care nurses who were responsible for the direct delivery of nursing care to patients and their families for at least 20 hours per week.

Materials and Measures

An electronic survey was used to capture both quantitative and qualitative data. Specific to this qualitative content analysis, the electronic survey consisted of five open-ended questions to identify the approaches used to facilitate family involvement in the care of critically ill patients. Participants were asked to provide responses for the following questions:

How do you determine to what extent families should be involved in ICU care?

How do you determine which family caregivers should be involved in care?

What barriers do you face in involving family caregivers in ICU care?

What concerns you most about involving family caregivers in ICU care?

What factors help you to involve family caregivers in ICU care?

In addition to the five open-ended questions, demographic and organisational characteristics were captured. These data included participants’ age, gender, race (White vs. Other), educational status, years of ICU experience, critical care registered nurse (CCRN) certification status, classification of ICU (adult vs. paediatric), Beacon- or Magnet-designated unit status, staffing ratio, job satisfaction (single-item indicator: Do you intend to leave your current position within the next 6 months?), and unit culture (single-item indicator: “Do you feel family caregivers are viewed as part of the team in your current unit?”).

Procedures

After receiving approval from the institutional review board at Case Western Reserve University (IRB-2016-1495), information about the study purpose and eligibility criteria were sent via email to AACN nurses and were posted on the AACN’s social media sites (July-August, 2016). Interested and eligible volunteers were instructed to click on a hyperlink that accessed the survey. All quantitative and qualitative data were captured using Qualtrics, an electronic data capture system. Participants were presented with an electronic cover letter that reiterated the purpose of the study, explained that completion of the electronic survey implied consent to participate, emphasised that participation was voluntary, and contained a consideration that the first 100 participants would receive a $5 electronic gift card. Completion of the survey took approximately 15 to 20 minutes. After participants submitted their responses, they received a message with the principal investigator’s contact information, thanking them for their participation. All responses were de-identified within the Qualtrics program.

Analysis

Qualitative content analytic methods were used to identify themes in the nurses’ responses to the open-ended survey questions (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Consistent with conventional qualitative content analysis, the text was read verbatim to interpret meaning and develop a coding scheme for the identification of categories and subcategories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Using the process of abstraction, categories and subcategories were combined until data was reduced to a few main categories, and these were named as themes (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). To assure rigor and trustworthiness, two researchers independently analysed the data and then shared their findings to determine similarities and differences in analyses. Data analysis was systematic, and both researchers followed the same steps to derive themes from the nurses’ responses. After determining overlapping ideas and prevalent themes collaboratively, the independent analyses of the researchers were integrated to produce a shared thematic analysis of the qualitative data meanings of the nurse participants.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

A total of 374 nurses provided a response to at least one of the five open-ended questions (Question 1 [n=373]; Question 2 [n=371]; Question 3 [n=371]; Question 4 [n=368]; Question 5 [n=356]). The majority of the sample were White (86%) and females (92%) between the ages of 30–49 (50%). Most had a bachelor’s degree or greater (82%), with varying years of critical care experience. Additional sample demographic information is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics (N=374)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Younger than 25 | 26 (6.9) |

| 25–29 | 71 (19.0) |

| 30–49 | 187 (50.0) |

| Older than 50 | 90 (24.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 30 (8.0) |

| Female | 342 (91.5) |

| Other | 2 (0.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 320 (85.6) |

| Other | 54 (14.4) |

| Highest Nursing Degree Earned | |

| Diploma | 8 (2.1) |

| Associate’s | 60 (16.0) |

| Bachelor’s | 239 (64.0) |

| Master’s | 59 (15.8) |

| Doctorate | 8 (2.1) |

| Years of Critical Care Experience | |

| Less than 1 year | 41 (10.9) |

| 1–5 years | 138 (36.9) |

| 6–15 years | 105 (28.1) |

| Over 15 years | 90 (24.1) |

| CCRN Certification | |

| Yes | 170 (45.5) |

| No | 204 (54.5) |

| Type of hospital currently working | |

| Academic Medical Center | 135 (36.1) |

| Community Hospital (teaching) | 115 (30.7) |

| Community Hospital (non-teaching) | 109 (29.1) |

| Military | 4 (1.1) |

| Other | 11 (2.9) |

| Hospital Location | |

| Urban | 289 (77.3) |

| Suburban | 70 (18.7) |

| Rural | 15 (4.0) |

| Magnet Status | |

| Yes | 146 (39.0) |

| No | 208 (55.6) |

| Unsure | 20 (5.3) |

| Type of unit | |

| Adult ICU | 296 (79.1) |

| Pediatric ICU | 26 (7.0) |

| Other | 52 (13.9) |

| Beacon Status | |

| Yes | 73 (19.5) |

| No | 210 (56.1) |

| Unsure | 91 (24.3) |

| Years worked on current unit | |

| Less than 1 year | 73 (19.5) |

| 1–5 years | 166 (44.4) |

| 6–15 years | 88 (23.5) |

| Over 15 years | 47 (12.6) |

| Intend to leave current position within 6 months | |

| Yes | 60 (16.0) |

| No | 314 (84.0) |

| Staffing ratio on unit | |

| 1 nurse to 1 patient | 17 (4.5) |

| 1 nurse to 2 patients | 321 (85.8) |

| 1 nurse to 3 patients | 21 (5.6) |

| Variable | 15 (4.0) |

| Visiting hours on unit | |

| Open visitation | 293 (78.3) |

| Limited visitation | 60 (16.0) |

| Other | 21 (5.6) |

| Caregivers viewed as part of team on unit | |

| Yes | 242 (64.7) |

| No | 132 (35.3) |

Main Findings

Our results indicated that the nurse, patient, and family each experience critical illness independently but have a triadic relationship. Interactions between the nurse, patient and family occur within the context of the professional practice environment and available resources for family care. The nurse, patient and family, as well as the professional practice environment and available resources for family care all have the potential to serve as either barriers or facilitators to family caregiver involvement in patient care (Figure 1). We identified two main themes from the analysis. The first theme was “Involving Family Caregivers in Patient Care in the ICU Requires Careful Assessment,” which contained three subthemes (Table 2): (1) extent to which nurses encourage families to participate in care, (2) determining which family caregivers should be involved in patient care, and (3) specific methods of family involvement. The second theme was “There Are Barriers and Facilitators to Caregiver Involvement in Patient Care in the ICU,” which contained five subthemes (Table 3): (1) family factors, (2) patient factors, (3) nurse factors, (4) professional practice environment, and (5) unit and organisational resources.

Figure 1.

Interaction Between Barriers and Facilitators and Their Influence on Family Involvement

Table 2.

Nurses’ Assessments Prior to Involving Family Caregivers in Patient Care

| Extent to Which Nurses Encourage Families to Participate in Care | |

| Factors that influenced the frequency and degree of family involvement |

|

| Rationale for Nurse Limits on Family Involvement |

|

| Determining Which Family Members Should be Involved in Patient Care | |

| Family Member Personal Qualities |

|

| Family Relationships and Dynamics |

|

| Nurse Criteria for Family Involvement | Family

|

| Specific Methods of Family Involvement | |

| Passive approach where families indicate interest in being involved |

|

| Active approach where nurses suggest involvement |

|

Table 3.

Barriers and Facilitators to Family Involvement in Care

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Family |

|

|

| Patient |

|

|

| Nurse |

|

|

| Professional Practice Environment |

|

|

| Unit and Organisational Resources |

|

|

Theme 1: Involving Family Caregivers in Patient Care in the ICU Requires Careful Assessment

Extent to which nurses encourage families to participate in care. Nurses shared that their decisions about the extent of family involvement were based on a number of factors, including beliefs and values regarding family involvement, knowledge and training, patient safety in the context of care, and factors related to their specific workplace. Nurses’ interpretation of the value and role of family guided their decisions to involve or limit family caregivers in patient care. Some nurses expressed complete support for the practice, while others said that family should not be involved at all. One nurse wrote, “There is always something the family can assist or participate in,” while another wrote, “Nurses cannot care for the family and patient at the same time—family takes away from patient care.” Nurses’ decisions were also influenced by beliefs about the clinical skill level required to participate in patient care. As one nurse stated, “As long as the family member is adequately trained, I do not have concerns.” Conversely, another nurse wrote, “If it is a skill learned in nursing school, it should only be done by me.”

Nurses described evaluating each case independently, as “each patient and family are different.” The extent of family involvement was also dependent on the safety of the patient, as evidenced by the statement, “Some of the family members are unfit and unsafe.” The context of care was an important consideration. One nurse described the progression of family involvement in neurological patients: “[I limit family] involvement at first with neuro patients [for safety], but as the patient progresses, family involvement helps support the patient physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually.” In contrast, end of life was universally accepted as an appropriate time for family involvement in care. A nurse explained, “If a patient is actively [dying] and especially if they are DNR or comfort care, I want [the family] by the bedside spending as much time as possible and bonding with their family member during those last possible moments.”

While many of the nurses shared the belief in practicing family involvement, some reported limiting family involvement when it was not universally supported by unit culture. As one nurse wrote, “Another nurse will follow me and contradict my allowing a family member to be involved in patient care, or will mock or criticise their involvement because of a lack of professional culture in the unit.”

Determining which family caregivers should be involved in patient care. Nurses reported that they assess family caregivers to determine whether they are able to participate in providing care. These assessments included the personal qualities of the family caregiver and the relationship dynamics between the caregiver and the patient, as well as relationships among family caregivers. While some nurses described their own “criteria” in great detail, others expressed frustration in not knowing how to best evaluate patients and family. Assessment of family caregivers’ personal qualities included physical and functional factors (e.g. physical strength), psychological and emotional factors (e.g. willingness to be involved, emotional stability), and knowledge (e.g. disease process, learning ability). Assessments of relationship dynamics included determining how caregivers were related to the patient (familial vs. non-familial relationship), whether the relationship appeared “healthy,” and the likelihood of the caregiver continuing care following discharge. Nurses also described feeling most comfortable involving immediate family members, spouses, powers of attorney for healthcare, adults, parents, grandparents, and legal guardians. They explained that their assessments are necessary to ensure safe and meaningful family involvement.

Some nurses stated that they use criteria, specific to both family caregivers and patients, that they believed would lead to greater success for family involvement in patient care, while remaining cognisant of the needs of the patient and family member. A paediatric nurse explained the importance of supporting family roles before delegating caregiver responsibilities. The nurse wrote, “We allow time for the parents to lay with the child in bed or hold the child, allowing them to be parents before they go to (patient) cares.”

Many nurses responded with fears and concerns about family members’ safety if helping with patient care, and potential liability issues if a negative patient outcome occurred as a result of a family member’s involvement. Nurses feared they may overwhelm family members in the following ways: (1) by asking them to perform patient care, (2) pushing family members to perform patient care before they feel ready, (3) family may blame themselves if something went wrong during their involvement in patient care, (4) the family may become unable to step away from active caregiving in order to make appropriate patient-related decisions. Nurses identified a variety of potential risks to the family members related to their active involvement in patient care: increased stress and anxiety, lack of self-care (i.e. not enough sleep), PTSD, caregiver fatigue, and a sense of failure if patient does not get better.

Specific methods of family involvement

Nurses chose to involve family members in a variety of ways. Some used a passive approach, waiting for family caregivers to come forward and indicate their interest to be involved; whereas other nurses outwardly expressed their support for family involvement and willingly invited them to participate in care activities. Nurses stated that initiation of family caregiving is often desirable and beneficial, yet complex, with many considerations for the patient, nurse, and family member. Nurses balanced the benefits of family involvement with potential risks. Basic and comfort cares, including “mouth swabbing,” “placing pillows,” “range of motion,” “rubbing backs,” “brushing teeth,” “applying lotion,” and “administering incentive spirometry,” were family activities supported by most nurses. Potential family caregiving responsibilities after discharge also guided nurses’ inclusion of family in patient care.

Nurses expressed various concerns for the family members as well as the patients when determining specific tasks for family caregiving. They were concerned about causing family members to feel overwhelmed or “pushed” to care for the patient before they were ready, that family member guilt was related to negative patient outcomes, or that families may push the patient too hard due to frustration. Nurses felt responsible for preventing potential risks when family caregivers were involved, including careful assessment of their stress and anxiety levels, their level of self-care (e.g. getting enough sleep), caregiver fatigue, PTSD symptoms, and sense of failure if a patient does not get better.

When encouraging family members to assist with care, nurses were sometimes concerned about “being judged” by families because they might perceive delegation of tasks as the nurse’s desire not to care for the patient. Furthermore, nurses expressed fears about safety and legal repercussions (lawsuits and risk to nurse licensure) associated with missing signs of clinical change in the patient if the family was performing tasks normally done by a nurse. Concerns regarding family members’ use of social media and documenting their involvement in patient care was viewed as a potential threat to patient privacy.

Theme 2: There Are Barriers and Facilitators to Caregiver

Involvement in Patient Care in the ICU. The nurses’ narratives about their assessments of involvement of family caregivers revealed specific facilitators and barriers related to family, patient, nurse, and professional environment factors, as well as unit and organisational resources.

Family factors

While many nurses wanted to involve family members in patient care, sometimes physical, emotional, and cognitive limitations were barriers to caregiver involvement and made nurses less likely to include the caregiver. Some nurses reported that a family member’s emotional state during such a high stress experience may impede their ability to participate in care. As one nurse noted, “Sometimes the ICU is [a] stressful environment for caregivers and it is difficult for them to grasp their limitations…they become unsafe.”

Unrealistic expectations were another family-associated barrier to involvement in care. Family member requests for nurse attention sometimes went beyond what nurses felt they were able to provide, leading to tension between the nurses and family members. This was a major challenge nurses faced when attempting to work with family members, as one nurse remarked, “They (family) expect nurses to be present 200% of the time and to cater to every need, no matter if it is small and non-life threatening.”

Nurse communication with family members, particularly early in the course of hospitalisation, was a facilitator to family involvement. Clarifying family caregivers’ preferences for how involved they wanted to be in providing patient care was important. Nurses were able to engage in this communication particularly well with families who remained at the bedside. By approaching caregiving early, nurses built trusting relationships with family members that led to successful caregiving involvement. Frequent communication and early family involvement led to better family understanding of the healthcare process because “[Family involvement] helps them (family) see what ‘do everything’ means for the patient in the hospital.”

Patient factors

High patient acuity was a major barrier to family involvement in care. Nurses explained that there are times when patients experience a decline in health and family involvement was not possible. The presence of lines, tubes, and equipment, and the extent of patient neurological compromise deterred nurses from involving family caregivers due to elevated patient safety risks. Conversely, some nurses observed patients respond to treatment more favourably and rest better when family was present, which encouraged them to involve family caregivers. Such positive patient responses (e.g. decreased anxiety, fear, stress) facilitated family involvement, and enhanced the patient’s safety and quality of care.

Nurse factors

The nurses’ attitudes towards family caregiver involvement in patient care could be both a barrier and facilitator. Some nurses were ambivalent about family caregiving due to previous experiences. For example, one nurse remarked that family caregiving is a “wonderful thing,” but experienced negative events in which family members silenced alarms, altered ventilator settings, and changed patient position. The threat to patient safety became a barrier to involving other family caregivers. However, many nurses expressed positive attitudes toward family caregiver involvement, which facilitated the practice and led to positive outcomes for patients, families, and even nurses. Some nurses described family caregiver involvement as accomplishing things they could not always do alone, such as being able to calm an anxious patient or being able to understand and meet the emotional needs of an agitated patient. Involving families also helped nurses to focus on higher priority or higher acuity work issues, which they believed helped the overall patient care process. One nurse remarked, “I find caregiver involvement is a huge asset to patient care and nurse stress. Family caregivers are able to free up a lot of the nurse’s time by performing helpful tasks that would otherwise have to be completed by the nurse.”

Proactive efforts to express understanding and the desire to form strong relationships with family members also facilitated the inclusion of family caregivers. When nurses related to and empathised with the experiences of the caregivers, higher quality relationships developed. Nurses took different approaches to gain the trust of family members (e.g. sharing their own experiences as family members or using a specific method to involve family caregivers), which ultimately facilitated healthy and effective involvement.

Professional practice environment

Aspects of the professional practice environment, including poor staffing, inadequate time to involve families, and a lack of perceived support from colleagues and unit leaders, were frequently cited as major barriers to involving family caregivers. Nurses remarked that when staffing is inadequate, they experience increased stress and decreased time, leading to de-prioritisation of family caregiver involvement. One nurse remarked, “I do not often get the time to explain and educate, and teach family members…It’s easier and quicker for me to just come into the room and do it myself.” Adequate personnel and support from individuals in leadership positions were facilitators of family involvement. Some nurses suggested that the presence of nonlicensed staff to perform care tasks could allow nurses to place more focus on caring for the family, thereby increasing the involvement of family caregivers in direct patient care.

Nurses also described challenges with other healthcare workers as barriers to family involvement, such as physician disagreement with family presence during medical rounds. Some fellow nurses did not support family caregiver involvement because families were considered an imposition. Multiple nurses remarked that nurse refusal to involve families was an antiquated attitude in the ICU. Divergent nurse attitudes and approaches led to conflicts among nurses and inconsistency in the treatment of family caregivers (e.g. one nurse permits, another nurse discourages). Nurses acknowledged these inconsistencies negatively influenced the quality of patient care.

Unit and organisational resources

Some nurses remarked that a major barrier to family caregiver involvement was inadequate resources to support family care. Desired resources included more space and the ability to facilitate better communication with family caregivers from different cultural backgrounds. Although many nurses supported family caregiver involvement, lack of unit and organisational resources made it difficult to facilitate the practice. One nurse explained,

Unfortunately, although our unit has open visitation, we have very few resources for the family. Basic things like a place to sleep are a challenge, as the unit was built prior to the open visitation policy and there is very little space for equipment. Plus, many of our patients come from long distances with little resources themselves, and we have little to help them stay healthy as they attempt to remain close to their loved ones. Oftentimes, I feel like we were set up to fail…

In contrast to lacking resources, a few nurses described unit characteristics and resources that facilitated family caregiver involvement in patient care, including private rooms, open visitation policies, and evidence-based education for nurses about family involvement in care and guidelines, policies, and/or protocols. Furthermore, the addition of suitable supplies and physical tools to facilitate hands-on family learning and teaching, such as iPads, videos, demonstration materials, and family-centred literature were proposed by nurses as ways to facilitate family involvement in care. In the words of one participant, to truly be successful with family involvement in care, there must be “A hospital wide and systemic change in culture and attitudes towards the family.”

DISCUSSION

This is the first known study to qualitatively explore nurse opinions of family caregiver involvement in direct patient care with a national sample of critical care nurses in the United States. Our results highlight the various assessments nurses complete to determine which family members to include in direct patient care, the extent to which family caregivers should be involved, and the factors that can hinder or facilitate the practice. We found overlapping nurse, patient, and family characteristics influence the degree to which family members are involved in the delivery of patient care in the ICU. The professional practice environment and the available unit and organisational resources determined the success or failure of nurses’ attempts to incorporate family as a care partner. While others have documented patient, family, and nurse factors as barriers to family involvement in care (McConnell & Moroney, 2015), a unique finding in our study was nurses’ identification of the professional practice environment and unit and organisational resources as facilitators and barriers to family involvement in the care of a critically ill patient. The workload burden associated with the care of critically ill patients, an ICU culture that was unsupportive of family involvement, a lack of policies and guidelines to enhance the practice, and inadequate interprofessional and nursing leadership support made it difficult for nurses to involve families in care. In contrast, the establishment of trusting relationships, frequent communication between nurses and families, positive patient responses to family caregiving, a professional practice environment that supports PFE (patient and family engagement), and resources for family care-enhanced family involvement. Although others have reported that nursing patient care responsibilities and patient acuity can negatively affect nurse interactions with family (Al-Mutair et al., 2013a; Segaric & Hall, 2015), our study is the first to emphasise the importance of a PFE culture, adequate resources for family care, and nurse leader support.

PFE remains a cornerstone of nursing family care (Brown et al., 2015); however, our findings provide evidence that it is not consistently translated into clinical practice. We found we a wide range of nurse attitudes and approaches to family involvement in ICU patient care, which contributed to inconsistent family involvement practices among critical care nurses. Variability in nursing delivery of family care interventions has also been documented in other studies (El-Masri & Fox-Wasylyshyn, 2007; Ganz & Yoffe, 2012; Liput et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2016). Prior research and the present study have shown that many nurses hold positive attitudes towards family involvement in care (Al-Mutair et al., 2013a; Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2010; Hammond, 1995; Hetland et al., 2017); however, this alone is not enough to support its consistent application at the bedside.

In the current study, nurses’ approaches to family involvement were not only dependent upon their beliefs, but were intricately tied to other factors related to the family, patient, professional practice environment, and available resources. Careful assessment of these factors guided nurse decisions about family involvement. We found that family factors played a vital role, which has been previously documented (Dinç & Gastmans, 2013; Hupcey, 1999; McConnell & Moroney, 2015; Nelms & Eggenberger, 2010; Segaric & Hall, 2015); however, the practices of other nurses, workload, and patient severity of illness also influenced nurse assessments of family caregivers for patient care. The specific care activities for family involvement varied; however, as in prior literature (Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2010; Hammond, 1995; Hetland et al., 2017; Liput et al., 2016), many nurses in our study described basic hygiene cares as acceptable activities for family caregivers. More complex cares, such as suctioning a tracheostomy, were considered too difficult. Nurse concerns about patient and family safety and legal repercussions were rationale for limiting family involvement, also consistent with findings from previous studies (Hammond, 1995; Liput et al., 2016; McConnell & Moroney, 2015).

Some nurses who responded in the current study did not know how to involve families. They posed questions about who should be involved and how they should be involved. This is an important finding indicating the need for interventions at the nurse level to promote family inclusion in care. Further nurse encouragement and support of family involvement facilitators is required to shift nursing culture towards family inclusion in care. Nurses have responded positively to interventions aimed at enhancing family care in the ICU in other studies (Eggenberger & Sanders, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2009). Although it is well documented family should be integrated into clinical care (Brown et al., 2015; Davidson et al., 2007, 2017), nurses require special knowledge, training, and resources to deliver family-focused clinical interventions. Nurse educational programs addressing family involvement in patient care is an opportunity for development and testing in future research, quality improvement initiatives, and PFE should be incorporated into nursing curriculum.

The diversity of opinion among nurses’ statements in the current study supports the unique challenge of delivering tailored interventions to family caregivers with limited resources and inadequate guidance. Although there was not complete agreement among nurses in our study regarding specific activities to involve families, the nurses emphasised the critical importance of family involvement when a patient is actively dying. This may be related to changes in nursing work flow that correspond with modification of treatment goals, and the perceived value of palliative approaches that incorporate family into a plan of care. Given the general consensus among these nurses on family involvement at end of life, exploring nurses’ rationale of family care inclusion for dying patients may be an opportunity to transition this practice into routine patient care.

In the current study, and in prior studies (Hetland et al., 2017; McConnell & Moroney, 2015; Segaric & Hall, 2015), the challenges of the professional practice environment suggest a negative influence on family care. There is a need to determine the optimal environment of care that supports family involvement (Hetland et al., 2017); Mitchell et al., 2016; Olding et al., 2015). From the limited research in this area and the findings in this study, nurses’ attitudes about family involvement seem to be closely intertwined with barriers that undermine their ability to involve and interact with family members, as well as the factors that promote family inclusion. Focusing on ways to overcome barriers and leverage existing facilitators is essential to increasing nursing support for family inclusion in care.

Limitations

One limitation is the possible response bias due to the convenience sampling technique used which allowed for nurses to self-select their participation. In addition, compared to the total number of members of AACN, a relatively small number of nurses chose to participate in the study further limiting the generalisability of survey results. Also, not all nurses in our sample provided responses to the open-ended items and the qualitative content analytic method used to examine this secondary data required personal interpretation of the data by the authors.

CONCLUSION

In this study, nurses shared their perspectives about factors that enabled or challenged family involvement in patient care. Active family involvement in routine care of ICU patients can reduce anxiety, increase family satisfaction, and contribute to feelings of family connection with the critically ill family member; however, family-centred care of critically ill patients remains an inconsistent practice and understudied area of nursing science. Organisational culture and the nursing work environment have been recognised as influential to the delivery of family-centred care; however, findings from the current study indicate a need for further investigation into these factors and their interaction with nursing family care. Greater attention to the professional practice environment in relationship to patient and family outcomes should be a priority in future research. Additionally, emphasis on translation of the PFE model into critical care nursing practice is required to transform family nursing care culture and practice. Despite the existing challenges of involving families in care, nurses are in an optimal position to partner with families. Nurses must be engaged in all efforts to improve patient and family care in the ICU environment.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE.

Family caregiver involvement can improve family experiences in the ICU; however, nurses use varying approaches to incorporate family caregivers into the direct care of critically ill patients.

Nurses’ decisions about involving family caregivers is based on assessment of factors related to the professional practice environment, family and patient characteristics, and the overall ICU unit culture.

Nurses have concerns regarding potential negative effects of family caregiver involvement, including overburdening family caregivers and exacerbating stress and anxiety for the involved family members. They also identified risks to patient and caregiver safety.

Nurses are more likely to endorse family caregiver involvement when there is a strong patient and family engagement culture, available family resources, and a healthy professional practice environment.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This publication was made possible by funding from a grant award 4T32NR014213-04 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NINR or the NIH.

Footnotes

Ethical Statement: Appropriate ethical approval for the conduction and dissemination of this study was obtained from the Intuitional Review Board (IRB) at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, OH, USA on 4/08/2016. The CWRU IRB Protocol Number is [IRB-2016-1495].

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O’Brian AP, Clerehan R. Attitudes of healthcare providers towards family involvement and presence in adult critical care units in Saudi Arabia: A quantitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2013a Mar;(23):744–755. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O’Brien A, Clerehan R. Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: A literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2013b;22(13–14):1805–1817. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Rozenblum R, Aboumatar H, Fagan MB, Milic M, Sarnoff Lee B, Turner K, Frosch DL. Defining patient and family engagement in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(3):358–360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1936LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JI, Herridge MS, Tansey CM, McAndrews MP, Cheung AM. Well-being in informal caregivers of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):81–86. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000190428.71765.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JI, Chu LM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Chan L, Thomas C, Friedrich JO, Mehtra S, Lamontagne F, Levasseur M, Ferguson ND, Adhikari NKJ, Rudkowski JC, Meggison H, Skrobik Y, Flannery J, Bayley M, Batt J, dos Santos C, Abbey SE, Tan A, Lo V, Mathur S, Parotto M, Morris D, Flockhart L, Fan E, Lee CM, Wilcox ME, Ayas N, Choong K, Fowler R, Scales DC, Sinuff T, Cuthbertson BH, Rose L, Robles P, Burns S, Cypel M, Singer L, Chaparro C, Chow CW, Keshavjee S, Brochard L, Hébert P, Slutsky AS, Marshall JC, Cook D, Herridge MS for the RECOVER Program Investigators (Phase 1: towards RECOVER and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group) One-year outcomes in caregivers of critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 374(19):1831–1841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Donahoe MP, Zullo TG, Hoffman LA. Caregivers of the chronically critically ill after discharge from the intensive care unit: Six months’ experience. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(1):12–23. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Powers K, Medayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, Spuhler V, Todres ID, Levy M, Barr J, Ghandi R, Hirsch G, Armstrong D American College of Critical Care medicine Task Force 2004–2005 Society of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Asiakson RA, Long A, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox C, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, Netzer G, Kentish-Barnes N, Sprung C, Hartog CS, Coombs M, Gerritsen RT, Hopkins RO, Franck LS, Skrobik Y, Kon A, Scruth EA, Harvey MA, Lewis-Newby M, White DB, Swoboda SM, Cooke CR, Levy M, Azoulay E, Curtis JR. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinç L, Gastmans C. Trust in nurse-patient relationships: A literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20(5):501–516. doi: 10.1177/0969733012468463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S, Daly B. Caregivers of long-term ventilator patients. CHEST. 2003;123:1073–1081. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger SK, Sanders M. A family nursing education intervention supports nurses and families in an adult intensive care unit. Aust Crit Care. 2016;29:217–233. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Masri MM, Fox-Wasylyshyn SM. Nurses’ roles with families: Perceptions of ICU nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2007;23:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry S, Warren NA. Perceived needs of critical care family members. Critical Care Nurs Q. 2007;30(2):181–188. doi: 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000264261.28618.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz FD, Yoffe F. Intensive care nurses’ perspectives of family-centered care and their attitudes toward family presence during resuscitation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27(3):220–227. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31821888b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrouste-Orgeas M, Millems V, Timsit JF, Diaw F, Brochon S, Vesin A, Philippart F, Tabah A, Coquet Il Bruel C, Moulard ML, Carlet J, Misset B. Opinions of families, staff, and patients about family participation in care in intensive care units. J Crit Care. 2010;25:634–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond F. Involving families in care within the intensive care environment: A descriptive survey. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1995;1:256–264. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(95)81713-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetland B, Hickman R, McAndrew N, Daly B. Factors that influence active family engagement in care among critical care nurses. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2017;28(2):160–170. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2017118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman R, Douglas S. Impact of chronic critical illness on the psychological outcomes of family members. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2010;21(1):80–90. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181c930a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupcey JE. Looking out for the patient and ourselves—the process of family integration into the ICU. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8:253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Better Together: Partnering with Families. [accessed 20.11.16];Facts and Figures about Family Presence and Participation. http://www.ipfcc.org/advance/topics/Better-Together-Facts-and-Figures.pdf.

- Johnson P, Chaboyer W, Foster M, van der Vooren R. Caregivers of ICU patients discharged home: What burden do they face? Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2001;17:219–227. doi: 10.1054/iccn.2001.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liput SA, Kane-Gill SL, Seybert AL, Smithburger PL. A review of the perceptions of healthcare providers and family members toward family involvement in active adult patient care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(6):1191–1197. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell B, Moroney T. Involving relatives in ICU patient care: Critical care nursing challenges. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:991–998. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M, Chaboyer W, Burmeister E, Foster M. Positive effects of a nursing intervention on family-centered care in adult critical care. Am J Crit Care. 2009;18:543–553. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M, Coyer F, Kean S, Stone R, Murfield J, Dwan T. Patient, family-centered care interventions within the adult ICU setting: An integrative review. Aust Crit Care. 2016;29:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms TP, Eggenberger SK. The essence of the family critical illness experience and nurse-family meetings. J Fam Nurs. 2010;16(4):462–486. doi: 10.1177/1074840710386608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olding M, McMillan SE, Reeves S, Schmitt MH, Puntillo K, Kitto S. Patient and family involvement in adult critical and intensive care settings: A scoping review. [accessed 6.10.16];Health Expectations. 2015 doi: 10.1111/hex.12402. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5139045/pdf/HEX-19-1183.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Segaric CA, Hall WA. Progressively engaging: Constructing nurse, patient, and family relationships in acute care settings. J Fam Nurs. 2015;21(1):35–56. doi: 10.1177/1074840714564787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society of Crit Care Med. [accessed 14.2.17];Critical Care Statistics. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.sccm.org/Communications/Pages/CriticalCareStats.aspx.

- Tyrie LS, Mosenthal AC. Care of the family in the surgical intensive care unit. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;30:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Weissfeld LA, Rotondi AJ, Schulz R, Chelluri L, Angus DC, Pinsky MR. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(2):167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]