Abstract

Background

Documentation of advance care planning for patients with terminal cancer is known to be poor. Here, we describe a quality improvement initiative.

Methods

Patients receiving palliative chemotherapy for metastatic lung, pancreatic, colorectal, and breast cancer during 2010–2015 at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario were identified from electronic pharmacy records. Clinical notes were reviewed to identify documentation of care plans in the event of acute deterioration. After establishing baseline practice, we sought to improve documentation of goals of care and referral rates to palliative care. Using quality improvement methodology, we developed a guideline, a standardized documentation system, and a process to facilitate early referral to palliative care.

Results

During 2010–2015, 456 patients were included in the baseline cohort: 63% with lung cancer, 16% with colorectal cancer, 13% with pancreatic cancer, and 7% with breast cancer. Care goals in the event of an acute illness were documented by medical oncologists in 6% of cases (26 of 456). Of the 456 patients, 47% (n = 214) were seen by palliative care; care goals were documented by palliative care in 48% of the patients seen (103 of 214). With those baseline data in hand, a local practice guideline and process was developed to facilitate the identification of patients for whom advance care planning and early palliative care referral should be considered. A system was also established so that goals-of-care documentation will be supported with a written framework and broadly accessible in the electronic medical record.

Conclusions

Low rates of documentation of advance care planning and referral to palliative care persist and have stimulated a local quality improvement initiative.

Keywords: Medical oncology, palliative care, goals of care

INTRODUCTION

It is not uncommon for patients with advanced cancer to become ill and to arrive to hospital having had no prior discussions about their goals of care (goc)1–7. A goc discussion is a communication process involving a physician and a patient or a substitute decision-maker (or all three) that is governed by informed consent and results in medical decisions within a plan of care. The discussions encompass many elements, including the patient’s understanding of his or her illness, symptoms, prognosis, and treatment options. They also delineate the patient’s life values and care wishes8. The absence of such discussions creates a challenging experience for patients, families, and health care providers alike, as the care team struggles to provide optimal care that aligns with the patient’s wishes and values in an emergent situation.

In that context, patients are at risk of receiving treatments that they might not have wanted or that could cause suffering with little chance of meaningful benefit. That potential disconnect has been highlighted in recent literature documenting a clear discrepancy between the wishes of patients and the care they receive9–12. In light of those concerns, there is a growing movement within oncology to encourage early discussions about goc13.

We recently reported initial results of a descriptive study to evaluate physician documentation of discussions related to prognosis and goc in patients with terminal lung or pancreatic cancer14. In a cohort of 222 patients receiving palliative chemotherapy for advanced lung or pancreatic cancer, initial results were concerning: Only 4% of patients with a life expectancy of less than 1 year had documentation of a care plan in the event of an acute deterioration, and only 39% had been referred to palliative care.

Findings from the initial study highlighted the need for a quality improvement (qi) initiative at our own centre. Before instituting such a qi initiative, we expanded our study to include patients with chemorefractory breast cancer and colorectal cancer. We also updated the dataset to obtain a contemporary baseline before initiating qi measures.

Here, we present the expanded dataset and outline the steps taken within our own centre to improve the rates of goc discussion and documentation. These updated data and practical qi initiatives could serve as examples for other cancer centres wanting to address similar gaps in care.

Scope of the Problem

Several studies have shown that the rates of goc discussions and code status documentation are low for patients with advanced cancer1–3,7. Temel and colleagues1 found that only 20% of patients with metastatic cancer at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center had a documented code status in their electronic medical record (emr). Another study from Canada showed that, of 209 patients referred for palliative radiotherapy over a 4-month period, only 13 (6.2%) had documentation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation–related advance directives7. Other single-institution reports show equally low rates in the 2%–7% range2,3.

In response to the mounting evidence that advance care planning (acp)—a communication process involving reflection, deliberation, and determination, wherein capable people discuss their values, wishes, and preferences with their substitute decision-maker and members of the health care team to prepare for future decisions or in the event that they cannot make their own decisions—are rare or, for patients with advanced cancer, occur late in the disease trajectory. Several guidelines now recommend that oncologists discuss acp with patients having stage iv cancer early during treatment13,15. As a result, recent qi efforts have focused on how best to translate those guidelines into practice in outpatients with advanced cancer.

A study by Obel and colleagues16 at the Kellogg Cancer Center showed that outpatient acp discussions were feasible in patients with recently diagnosed stage iv lung cancer. Improvement in workflow and involvement of motivated providers were key elements that resulted in almost 70% of patients having notes about advance directives in their medical record. In addition, a targeted approach to identifying patients who qualify for acp discussions has been shown to increase uptake in patients who engage in acp discussions17. Studies have shown that various strategies, including identifying patients from health records18, providing electronic prompts for physicians19, and educating staff and regularly reporting results17,18 can increase the rate of goc documentation.

METHODS

Baseline Rates of GOC Documentation at Our Centre

After obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Board of Queen’s University, we conducted a retrospective single-institution cohort study. The study population included all patients with metastatic pancreatic, lung, colorectal, or breast cancer receiving chemotherapy with palliative intent at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario (ccseo) between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2015. Our initial study results were limited to 2010–2013 and included only patients with pancreatic cancer and lung cancer13. Here, we present updated data that now also include patients with chemorefractory breast and colorectal cancer.

The ccseo is a comprehensive academic cancer centre affiliated with Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, which has a catchment population of approximately 500,000 people. Selection criteria included patients initiating first-line palliative chemotherapy for lung and pancreatic cancer, second-line palliative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer, and third-line palliative chemotherapy for breast cancer. The inclusion criteria were chosen to capture a cohort of patients with a life expectancy of less than 1 year. Electronic pharmacy records were used to identify potentially eligible participants. Patients with locally advanced disease and no evidence of distant metastasis were excluded. To be included in the study, patients were required to have attended at least 4 clinic visits (2 of which had to have occurred after initiation of palliative chemotherapy). This latter criterion ensured that the study population would have an existing therapeutic relationship with a medical oncologist and adequate continuity of care to allow for discussions related to acp. All clinical notes by the medical oncologist within the electronic chart were reviewed from the time of consultation until 2 visits after the initiation of chemotherapy. After the patient’s initial visit with medical oncology, all notes from palliative care providers were also reviewed. Patient demographics, treatment data, and goc or acp documentation were captured in an electronic database by a single investigator (WR).

Of the 737 potentially eligible patients identified in electronic pharmacy records during 2010–2015, 281 were excluded for one of the following reasons: they had locally advanced but not metastatic disease (n = 59), they did not receive palliative-intent chemotherapy (n = 20), they had other primary cancers (n = 12), they had fewer than 4 clinic visits with medical oncology (n = 112), they had received an inadequate number of prior lines of palliative chemotherapy for breast cancer or colorectal cancer (n = 51), or because they had been treated outside study time period (n = 27). Table i shows the characteristics of the 456 patients included in the study population.

TABLE I.

Characteristics of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy for metastatic lung, pancreatic, breast, or colorectal cancer at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario, 2010–2015

| Characteristic | Value [n (%)]a |

|---|---|

| Patients | 456 |

| Age group | |

| <50 Years | 28 (6) |

| 50–59 Years | 108 (24) |

| 60–69 Years | 161 (35) |

| 70–79 Years | 130 (29) |

| ≥80 Years | 29 (6) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 220 (48) |

| Women | 236 (52) |

| Year | |

| 2010 | 64 (14) |

| 2011 | 69 (15) |

| 2012 | 71 (16) |

| 2013 | 88 (19) |

| 2014 | 98 (22) |

| 2015 | 66 (14) |

| Disease site | |

| Lung | 289 (63) |

| Pancreas | 59 (13) |

| Colon or rectum | 75 (16) |

| Breast | 33 (7) |

Percentages might not add to 100% because of rounding.

Most patients (63%) were being treated with first-line palliative chemotherapy for lung cancer. Consistent with our initial analysis, a care plan in the event of an acute deterioration was documented by medical oncologists in only a very few patient charts (6%). Of the 456 included patients, 47% (n = 214) had been referred to palliative care. Palliative care physicians documented care plans in the event of an acute deterioration for almost half the patients who were referred (103 of 214, 48%).

Compared with our earlier analysis, the patient population included proportionally fewer patients with lung cancer (80% vs. 63%), chiefly because the dataset had been expanded to 2 new sites, breast and colorectal cancer. The inclusion of breast cancer led to a slight female predominance compared with the earlier cohort (52% vs. 46%), but the distribution of age was similar (one third of the patients were 70 years of age or older). A greater proportion of patients in the expanded dataset had been seen by palliative care (47% vs. 41%). The proportion of patients with goc documented by palliative care physicians also significantly increased over time (to 65% in 2015 from 14% in 2010, p < 0.001 for temporal trend; Table ii).

TABLE II.

Documentation of goals-of-care discussions with patients receiving palliative chemotherapy for metastatic lung, pancreatic, breast, or colorectal cancer at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario, 2010–2015

| Discussion item | Documenter [n (%)]b | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Medical oncologist | Palliative care physician | |

| Patients | 456 | 214 |

| Goals of care | ||

| Documented | 26 (6) | 103 (48) |

| Not documented | 430 (94) | 112 (52) |

| Outcome of discussion | ||

| Not discussed | 430 (94) | 112 (52) |

| Symptom management | 3 (1) | 16 (8) |

| Medical interventions | 16 (4) | 56 (26) |

| Life sustaining measures | 1 (0) | 7 (3) |

| CPR | 4 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Not stated | 2 (0) | 18 (8) |

Only the first discussion of goals of care was captured in the study dataset for each patient. If a subsequent discussion took place, it was not measured. Data reflect only the initial discussion.

Percentages might not add to 100% because of rounding.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initiating a Local QI Initiative

Having measured our baseline rates of documented care plans in the event of acute deterioration, and the rates of palliative care consultation, we used the PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) methodology to design a qi initiative20.

Plan

Our first step was to identify at-risk patients who would benefit from goc discussions and a referral to palliative care. That step required input from medical oncologists, nurses, and patient care coordinators at the ccseo. A project team was assembled with representation from each of those groups.

The group referred to the Early Identification and Prognostic Indicator Guide (suggested by Cancer Care Ontario)21 to draft a guideline that would identify the target population. The aim was to use patient factors that could be identified electronically to create a well-defined and accessible patient population. The draft proposal included patient variables such as a high symptom burden, disease parameters such as cancer site, treatment factors such as third-line palliative-intent chemotherapy, and provider variables such as the question “Would you be surprised if this patient died within the next 12 months?”

The initial guideline was circulated to project team members and to other important stakeholders, including oncology and palliative care providers, residents, nurse practitioners, clinical educators, and social workers. Revisions were made accordingly. The guideline was then circulated to the oncology department staff and was approved before implementation. Table iii summarizes the final guideline.

TABLE III.

Advance care planning guideline (summary) adopted by physicians at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario in May 2016

| Patient parameter | Palliative care referral? | Goals of care and advance care planning discussion? | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with complex symptom burden from cancer or treatment-related toxicity, or both, with symptom severity scores greater than 4/10 that persist for more than 3 visits. | Yes | To be considered based on other prognostic parameters | Not all patients with complex symptom burden are in the late or incurable phases of their disease, but all patients will benefit from palliative care referral. |

| Patients whose physician answered “no” to the question “Would you be surprised if this patient died within the next 12 months?” | Yes | Yes | Goals of care and advance care planning discussions might not require palliative care referral; discussions could be handled by oncologists and documented appropriately in the patient’s chart. It is recommended that these be dynamic discussions, such that specific elements will have to be readdressed depending on changes in the health care status of the patient. |

Patients with general indicators of decline such as

|

Yes | Yes | Goals of care and advance care planning discussions should be coordinated between the palliative care physician and the oncology most-responsible physician if the patient is still receiving disease-directed therapies. |

The guideline confirmed the definition of acp. The ultimate goal was to ensure that documentation of goc and acp discussions and plans is present and accessible across time and place within the health care system.

The guideline recommends that all members of the health care team at the ccseo identify individuals who could benefit from goc discussions, acp discussions, and referral to palliative care.

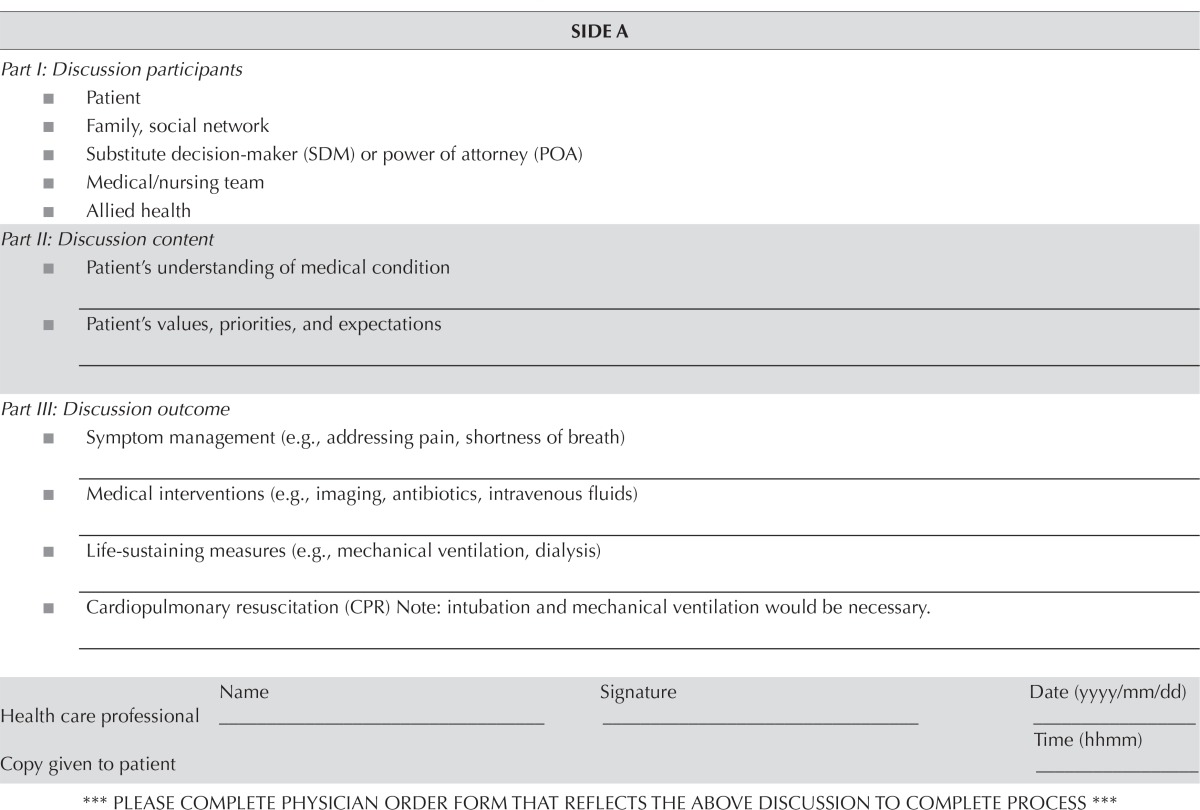

Early on, it was recognized that, even for the small number of patients with a documented goc or acp discussion, the conversation was buried in clinical notes within the emr and were not readily available to other physicians in the cancer centre, to acute-care inpatient units, or to the emergency department. Wilson et al.22 similarly showed that the location of acp documentation within their emr was not standardized, making it difficult to make care decisions when time was limited. Their solution was to create a button within the emr called Advanced Directive/Code Status that would provide access to all stored acp and code status documentation. At our centre, the Internal Medicine program had recently developed a goc documentation tool for patients admitted to their service. Rather than create a new form, we chose to use the same tool to formalize goc documentation for our outpatient oncology patients (Table iv). That form was called the Blue Sheet. In addition, we requested that a button labelled Life Care Plans be added to the home screen of the emr. Upon completion of a Blue Sheet, a member from health records would scan the document into the emr within 2 business days. Because acp is a dynamic process that can evolve over time, an updated Blue Sheet can be uploaded as required at any time in the future.

TABLE IV.

Content of Blue Sheet documentation tool for patient goals of care at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario

| SIDE A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part I: Discussion participants | |||

| ■ Patient | |||

| ■ Family, social network | |||

| ■ Substitute decision-maker (SDM) or power of attorney (POA) | |||

| ■ Medical/nursing team | |||

| ■ Allied health | |||

| Part II: Discussion content | |||

| ■ Patient’s understanding of medical condition _______________________________________________________ | |||

| ■ Patient’s values, priorities, and expectations ________________________________________________________ | |||

| Part III: Discussion outcome | |||

| ■ Symptom management (e.g., addressing pain, shortness of breath) ________________________________________________________ | |||

| ■ Medical interventions (e.g., imaging, antibiotics, intravenous fluids) ________________________________________________________ | |||

| ■ Life-sustaining measures (e.g., mechanical ventilation, dialysis) ________________________________________________________ | |||

| ■ Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) Note: intubation and mechanical ventilation would be necessary. ________________________________________________________ | |||

| Name | Signature | Date (yyyy/mm/dd) | |

| Health care professional | ____________________ | ____________________ | ____________________ |

| Time (hhmm) | |||

| Copy given to patient | ____________________ | ||

| *** PLEASE COMPLETE PHYSICIAN ORDER FORM THAT REFLECTS THE ABOVE DISCUSSION TO COMPLETE PROCESS *** | |||

| SIDE B | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Goals of Care Discussion Resource – Meeting Checklist | |

| Side A should be used to document the discussion participants, content, and outcomes. Side B is a checklist to assist in the preparation of the meeting further information and references are available on “Goals of Care Discussion Resource – Supplemental Information” (see barcode at bottom) | |

| I. | Preparing for discussion |

| □ Assess patient’s capacity for consent and/or if an advance directive already exists. | |

| □ Obtain patient’s permission for a family meeting. Determine degree to which patient wishes to be involved. | |

| □ Identify other key attendees (e.g., family members, substitute decision maker, interpreter). | |

| □ Identify members of the health care team that should attend and organize logistics (include Social Work). | |

| □ Review the patient’s chart. Identify any specific issues that may need to be addressed. Be prepared to formulate recommendations for care. | |

| II. | Holding the meeting |

| □ Open the meeting by explaining what you wish to discuss (e.g. goals of care). | |

| □ Elicit the patient’s understanding of their condition. | |

| □ Elicit the patient’s values, beliefs, fears, goals, and expectations. | |

| □ Identify or appoint a substitute decision maker or power of attorney. | |

| □ Provide information about the different levels of intervention. Confirm patient’s understanding. Welcome questions. | |

| □ Discuss these interventions further in relation to the patient’s health condition and future options. Acknowledge the patient’s reaction, and address emotions. | |

| Remember: Be compassionate, but direct. | |

| III. | Meeting outcomes |

| □ Document the content of discussion and levels of intervention. Include comments for each level regardless of decision (e.g., if decision for no CPR, can write “CPR discussed and declined after possible outcomes reviewed.”) | |

| □ Organize any follow-up or further meetings that may be required. | |

| □ Have the patient (or representative) and a physician sign the document. | |

| □ Provide a copy of the document to the patient and/or family. | |

Next, the project team identified a goal for the qi initiative. The primary improvement goal was to increase the rate of goc documentation to 40% from 6% in an atrisk population of cancer patients by 31 August 2017. The secondary goal was to increase referral rates to palliative care to 70% from 47% over the same period.

Finally, the project team decided on a two-phase intervention to achieve the improvement goals. Phase 1 of the project (“the passive phase”) involved having the Blue Sheet available in all outpatient clinics at the ccseo. The medical oncologists were encouraged to use the Blue Sheet with any patient who met the criteria outlined in the guideline. In addition, they were also encouraged to refer patients with advanced disease to palliative care early in the course of treatment. This phase of the project was meant to ensure the feasibility of the Blue Sheet and was therefore not limited to the selected population from the baseline study.

Phase 2 of the project (“the active phase”) actively sought to increase goc documentation by identifying at-risk patients and providing physician prompts and reminders. Patients are identified using pharmacy chemotherapy records that meet our selection criteria (as identified in the updated baseline study) based on disease site, stage, and intent of therapy. For those patients, the Blue Sheet is placed in the patient’s chart before the patient is seen by the medical oncologist. The sheet thus serves as a visual reminder that the patient has been identified as requiring a goc discussion. The rates of goc documentation and palliative care referral were tracked on a monthly basis.

Do

The passive phase of the project took place from 1 June to 31 October 2016. The active phase began on 1 November 2016 and is ongoing.

Study and Act

Preliminary results from the passive phase of the project were reviewed. Over the 5-month period allocated to this phase, Blue Sheets were completed for 44 patients. Of the 44 completed sheets, 15 were completed by 6 medical oncologists, and the remaining 29 were completed by 4 palliative care physicians.

Before the start date of the active phase, the medical oncologists were reminded of the initiative by e-mail. In addition, the project team decided to provide a further monthly prompt to the medical oncologists. For a given month, the project coordinator would send each medical oncologist a confidential e-mail containing the names of patients who had been identified as requiring goc discussion and documentation.

The active phase ended on 31 August 2017, and an analysis of the results is ongoing. The PDSA cycle will be repeated based on a review of those results.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations that warrant mention. First, the duration of the review (10 months) after the intervention (“active phase”) might have been inadequate to notice a change in practice. In addition, an assessment for sustainability and continual improvement will not be possible after the end of the project. Second, given that the study population includes only patients with metastatic lung, pancreatic, breast, and colorectal cancers, our findings might not be able to be extrapolated to patients with other cancers having prognoses of less than 1 year. Finally, although we have outlined a process that was successful at our cancer centre, other centres that lack similar resources (specifically, emrs) might not be able to replicate our efforts. Despite those limitations, we feel that other cancer centres and oncologists can gain significant insights from the implementation and design of our qi project.

SUMMARY

In this report, we described the early phase of our qi initiative to improve goc documentation in patients with advanced cancer at our centre. We used qi methodology and frameworks developed through other qi initiatives to inform our project design. The process we used, as summarized here, might be helpful for other cancer centres wishing to implement similar initiatives.

-

■

Based on anecdotes and clinical impressions, we identified a potential problem within our current practice environment.

-

■

To understand the extent of the potential problem, we undertook initial data collection for a cohort of patients with advanced lung cancer and pancreatic cancer treated with chemotherapy during 2010–2013 (initial results recently published)13.

-

■

Data from the initial study were presented on several occasions to the medical staff at the ccseo (medical oncology, radiation oncology and palliative care) at monthly oncology department meetings.

-

■

Together with other clinical colleagues and with the use of an existing framework, we drafted a cancer centre guideline to provide a structure for how and when to engage in goc and acp conversations and when to refer patients to palliative care (Table iii). Initial draft guidelines were presented to physician stakeholders at departmental meetings and were subsequently revised based on feedback provided.

-

■

We recognized that the current method for documenting goc and acp discussions (in the clinic notes) were not readily accessible to other physicians in the cancer centre, to acute-care inpatient units, or to the emergency department. Accordingly, we adopted an existing form that had been recently developed by the medical inpatient units (the Blue Sheet). In addition, based on experience from other institutions, we standardized the location of the documentation within the emr.

-

■

Finally, we designed a two-phase qi intervention to determine the feasibility of using the Blue Sheet in the outpatient setting and to increase rates of goc documentation and of referral to palliative care. Before launching the initiative, we updated our “pre-intervention” baseline database and expanded the target patient population to include patients with chemorefractory metastatic breast cancer and colorectal cancer. We clearly outlined our improvement goals and the timeline over which progress was to be measured.

Results from the early phase of our initiative show that implementation of a goc documentation tool (the Blue Sheet) is feasible in the outpatient setting for patients with advanced cancer. Further analysis of the active phase of the project will determine whether the intervention increased the rates of goc documentation and referral to palliative care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Jennifer O’Donnell and Angela Truesdell. CMB is supported as the Canada Research Chair in Population Cancer Care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Code status documentation in the outpatient electronic medical records of patients with metastatic cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:150–3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1161-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranganathan A, Reardon D, Evans TL. Documentation of code status at an outpatient academic cancer center: a marker of discussing end-of-life preferences [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:307. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.30.34_suppl.307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton JM, Hwang M, Ma JD, Roeland E. A single-center, retrospective chart review evaluating outpatient code status documentation in the epic electronic medical record [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:242. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.31.31_suppl.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;24:1616–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pronzato P, Bertelli G, Losardo P, Landucci M. What do advanced cancer patients know of their disease ? A report from Italy. Support Care Cancer. 1994;2:242–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00365729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranganathan A, Gunnarsson O, Casarett D. Palliative care and advance care planning for patients with advanced malignancies. Ann Palliat Med. 2014;3:144–9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2014.07.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley NM, Sinclair E, Danjoux C, et al. The do-not-resuscitate order: incidence of documentation in the medical records of cancer patients referred for palliative radiotherapy. Curr Oncol. 2006;13:47–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinuff T, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. Improving end-of-life communication and decision making: the development of a conceptual framework and quality indicators. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1070–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somogyi-Zalud E, Zhong Z, Hamel MB, Lynn J. The use of life sustaining treatment in hospitalized persons aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:930–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland DK, Lavery JV, Tranmer JE, Shortt SED. The final days: an analysis of the dying experience in Ontario. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can. 2000;33:356–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyland DK, Lavery JV, Tranmer JE, Shortt SE, Taylor SJ. Dying in Canada: is it an institutionalized, technologically supported experience ? J Palliat Care. 2000;16(suppl):S10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. on behalf of the Advance Care Planning Evaluation in Elderly Patients Study Team and the Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:778–87. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ASCO Institute . Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) [Web page]. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2014. [Available at: http://www.instituteforquality.org/quality-oncology-practice-initiative-qopi; cited 10 November 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raskin W, Harle I, Hopman WM, Booth CM. Prognosis, treatment benefit and goals of care: what do oncologists discuss with patients who have incurable cancer? Clin Oncol. 2015;28:209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy MH, Back A, Benedetti C, et al. nccn Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: palliative care. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2009;7:436–73. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obel J, Brockstein B, Marschke M, et al. Outpatient advance care planning for patients with metastatic cancer: a pilot quality improvement initiative. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1231–7. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schofield G, Kreeger L, Meyer M, et al. Implementation of a quality improvement programme to support advance care planning in five hospitals across a health region. 2015;5:91–4. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neubauer MA, Taniguchi CB, Hoverman JR. Improving incidence of code status documentation through process and discipline. J Oncol Pract. 2013;11:e263–6. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Temel JS, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, et al. Electronic prompt to improve outpatient code status documentation for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:710–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the Plan-Do-Study-Act method to improve quality in healthcare. 2014;23:290–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Early Identification and Prognostic Indicator Guide. Mississauga, ON: Mississauga Halton Regional Hospice Palliative Care; n.d.. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson CJ, Newman J, Tapper S, et al. Multiple locations of advance care planning documentation in an electronic health record: are they easy to find? J Palliat Med. 2013;16:1089–94. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]