Abstract

Relatively little attention has focused on how pesticides may affect Asian honey bees, which provide vital crop pollination services and are key native pollinators. We therefore studied the effects of a relatively new pesticide, flupyradifurone (FLU), which has been developed, in part, because it appears safer for honey bees than neonicotinoids. We tested the effects of FLU on Apis cerana olfactory learning in larvae (lower dose of 0.033 µg/larvae/day over 6 days) and, in a separate experiment, adults (lower dose of 0.066 µg/adult bee/day) at sublethal, field-realistic doses given over 3 days. A worst-case field-realistic dose is 0.44 µg/bee/day. Learning was tested in adult bees. The lower larval dose did not increase mortality, but the lower adult dose resulted in 20% mortality. The lower FLU doses decreased average olfactory learning by 74% (larval treatment) and 48% (adult treatment) and reduced average memory by 48% (larval treatment) and 22% (adult treatment) as compared to controls. FLU at higher doses resulted in similar learning impairments. The effects of FLU, a pesticide that is reported to be safer than neonicotinoids for honey bees, thus deserve greater attention.

Introduction

Global concern has grown over the effects of pesticides1, particularly neonicotinoids, on beneficial pollinators2. Honey bees play an important role in pollinating crops3 and are therefore widely and common exposed to pesticides, which have multiple individual effects, even at sublethal doses4–6 and can interact with other factors that reduce bee health, including parasite infections and viral diseases7. Interest has therefore grown in new pesticides that could reduce this harm. However, researchers have largely focused upon a single species, Apis mellifera 8, even though Asian honey bee species are also vital. Apis cerana has a wide range extending from China to India, including southern and eastern Asia9 over which it provides important ecosystem services3,10,11 and is a key pollinator of native plant species10,12. Although A. cerana is evidently more resistant to some parasites13 and pathogens14 than A. mellifera, the health of this species is also of concern15–17. More than two million managed colonies of A. cerana are used in China for crop pollination and honey production10. Apis cerana is thus exposed to multiple pesticides18, including newly registered compounds.

Flupyradifurone (FLU) is a butenolide systemic insecticide whose chemical structure was designed based upon a natural compound, stemofoline, found in the Asian medicinal plant, Stemo japonica 19. Like the neonicotinoids, stemofoline acts upon insect nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)20. Modifications of stemofoline’s structure resulted in the creation of FLU19, which was first commercially registered in Guatemala and Honduras in 201419. Since then, FLU has been registered for use on a wide variety of crops in the USA21, Europe22, and China23. Common agricultural applications include use on citrus, cocoa, cotton, grapes, hops, pome fruits, potatoes, soybeans, and ornamental plants19.

FLU has a far lower binding affinity to insect nAChRs than neonicotinoids, but can be effective against plant sucking insects, particularly those that have developed resistance to neonicotinoids19. In addition, studies suggest that FLU has a relatively low impact on A. mellifera 24. For example, A. mellifera colonies placed in plots adjacent to fields sprayed with FLU were exposed to low levels of FLU, but did not have different colony strength parameters (numbers of adult workers, eggs, brood cells, food storage cells, and colony mass) as compared with controls25. However, to date, no studies have examined the impact of FLU on A. cerana, even though a meta-analysis suggested that A. cerana is more susceptible to some pesticides than A. mellifera 26. Neonicotinoid pesticides, which also act upon nAChRs, may exert a stronger detrimental effect27, up to 10-fold higher28, on A. cerana as compared to A. mellifera. However, the meta-analysis conducted by Arena and Sgolastra26 found that neonicotinoids had a similar effect upon both species. In general, the effects of nAChR agonists on different target species are difficult to predict a priori 29, and experiments are therefore needed.

The majority of pesticide studies conducted with honey bees focus on lethality and overall colony effects30. However, the effects of pesticides should be assessed on multiple aspects of pollinator health and biology31. For example, honey bees are noted for their olfactory learning32. Olfactory learning is key to colony food intake and the pollination services provided by honey bees because it allows bees to associate odors with nectar and pollen rewards, thereby helping them to find rewarding food and assisting pollination by facilitating floral constancy32. Multiple studies have shown that neonicotinoids and other pesticides can impair olfactory learning in bumble bees33 (though not all ref.34) and in honey bees (A. mellifera 35–42 and A. cerana 43,44). To date, no published studies have examined the effects of FLU on honey bee learning.

Honey bees can be exposed to pesticides at multiple life stages, including the larval stage45, which may be more sensitive to such toxins37,43. Yang et al.37 demonstrated that A. mellifera fed imidacloprid as larvae had reduced olfactory learning when they became adults, even though the larvae were fed much smaller imidacloprid doses than are required to impair adult learning36,37,46. It was unknown if FLU would similarly affect A. cerana larvae or adults. We thus tested the sublethal effects of FLU on survival and olfactory learning when bees were exposed as larvae or as adults.

Results

FLU residues are detectable from the inflorescences of a wide variety of crops (including apple) for 7 days after foliar application24. A high field-realistic dose of FLU is 0.44 µg/forager/day (from bees foraging on apple blossoms)24. All of our lower FLU doses and exposure durations were field-realistic, based upon this forager data (0.033 µg/larvae/day and 0.066 µg/adult bee/day). Full details on doses and concentrations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Doses and concentrations of flupyradifurone (FLU) fed to larvae and adults. Field-realistic doses are 0.44 µg/bee/day24 and concentrations of 4.1–4.3 ppm in forager honey stomachs MRID 48844516 and MRID 48844517 in 24. Calculations of ppm are based upon the density of pure sucrose solution (1.127 g/ml) at 1 ATM and 21 °C. The molecular weight of FLU is 288.68 g/mole.

| TREATMENT PER BEE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosea | Concentration | |||||||

| Experiment | Feeding schedule | Volume fed (1 M sucrose solution) | Level | µg per feeding | nmoles per feeding | mg/L per feeding | nmoles/L per feeding | mg/Kg (ppm) |

| Larval exposure | Each 24 h for 6 d | 2 µl | Control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (6 total feedings) | 2 µl | Lower | 0.033* | 0.11* | 1.65 | 57.16 | 14.64 | |

| 2 µl | Higher | 0.33* | 1.14* | 16.5 | 571.57 | 146.41 | ||

| Adult exposure | Each 12 h for 3 d | 20 µl | Control | 0b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (6 total feedings) | 20 µl | Lower | 0.033*b | 0.11* | 1.65* | 5.72* | 1.46* | |

| 20 µl | Higher | 0.33*b | 1.14 | 16.5 | 57.16 | 14.64 | ||

aFor larvae and adults, each bee was fed a total of 0, 0.2, or 2.0 µg/bee after chronic exposure over multiple days (6 total feedings/bee).

bBecause adult-treated bees were fed twice each day, daily FLU doses for adults were 0, 0.066*, and 0.66 µg/bee/day.

*Daily doses and concentrations that are field-realistic based upon data collected from foragers (see Methods).

Larval exposure experiment

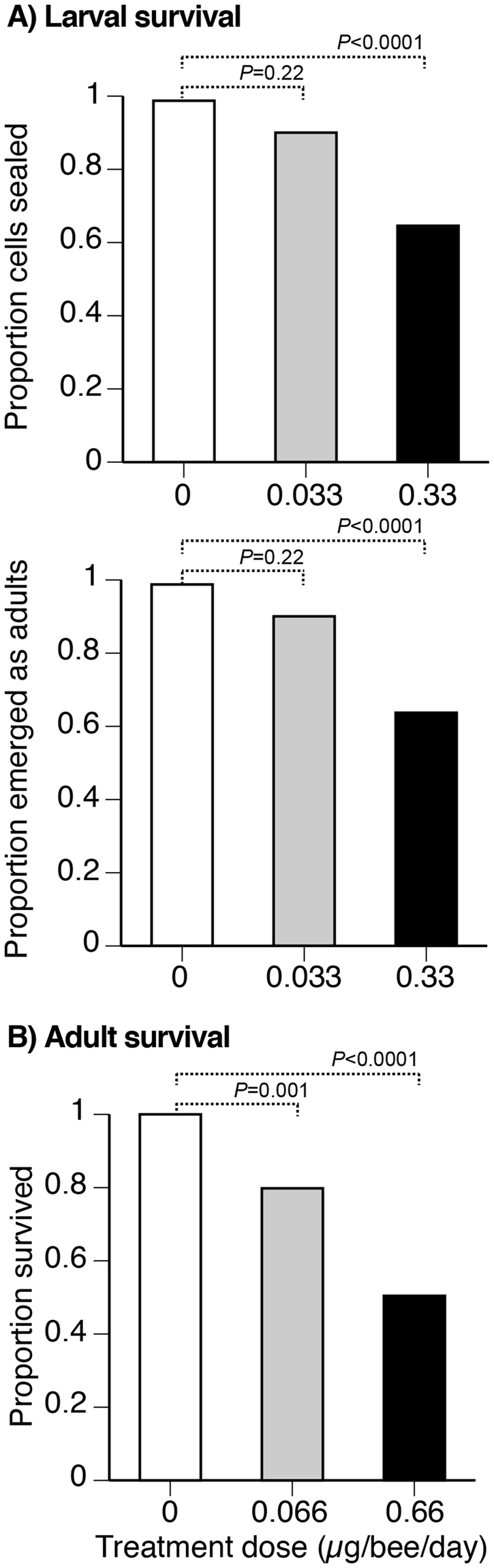

Flupyradifurone reduced larval survival

We fed larvae for 6 d, beginning at 1 d of larval age. Nearly 100% of control larvae (0 µg FLU) survived to the cell sealing phase and emerged as adults (Fig. 1A). The lower dose of 0.033 µg/bee/day did not significantly alter larval survival to the sealed cell phase or survival to emergence (Fisher’s Exact tests, P = 0.22). However, the higher dose (0.33 µg/bee/day) significantly reduced survival to the sealed cell phase (−34%, Fisher’s Exact test, P < 0.0001Dunn-Sidak corrected=DS) and reduced adult emergence (−35%, Fisher’s Exact test, P < 0.0001DS) as compared to control bees.

Figure 1.

Effects of flupyradifurone on the survival of (A) larvae and (B) adults. Proportions were calculated based upon the number of initially treated larvae. The P-values are from Fisher’s Exact tests, with dashed lines connecting the groups being compared.

Flupyradifurone reduced learning

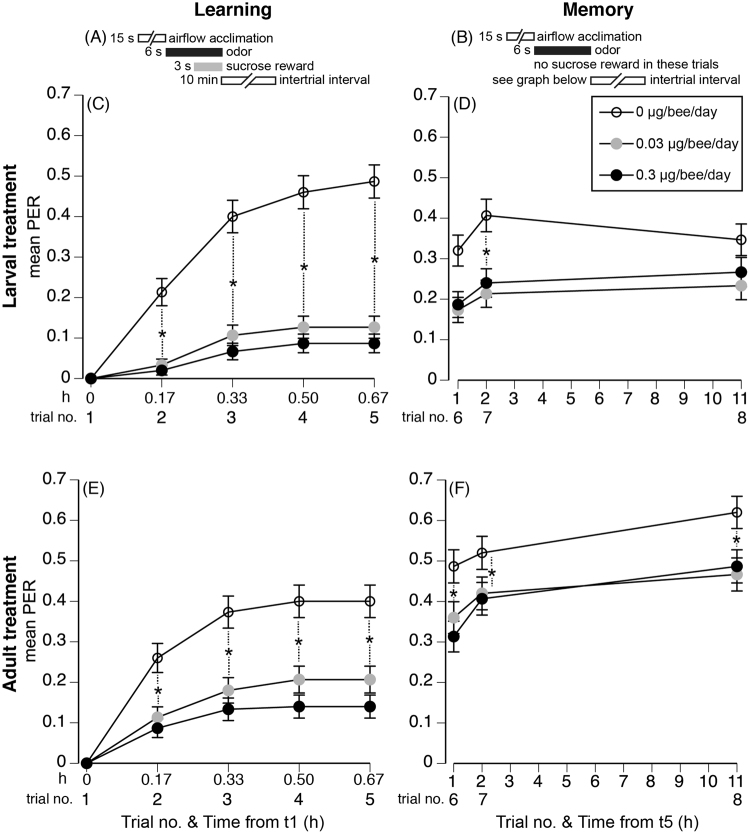

A honey bee exhibits learning when it extends its proboscis (PER) in response to a previously rewarded odor32. Larval-treated bees showed learning (significant trial effect: F 4,1788 = 100.14, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2C). We then conducted all pairwise comparisons (Tukey HSD test) and report the ones of interest. For each treatment, bees exhibited learning when the 1st trial (before learning) and 5th trial (after four rewarded odor presentations) were compared (Tukey HSD test t1 vs. t5, P < 0.05). However, control bees (0 µg FLU/bee/day) showed learning after just a single rewarded trial (Tukey HSD test t1 vs. t2, t3, t4, and t5, P < 0.05). Lower-dose bees (0.033 µg FLU) showed learning only after the 3rd trial (Tukey HSD test t1 vs. t3, t4, and t5, P < 0.05). Higher-dose bees (0.33 µg FLU/bee/day) learned only after the 4th trial (Tukey HSD test t1 vs. t4 and t5, P < 0.05). Thus, there was a significant interaction of trial*dose (F 8,1788 = 27.31, P < 0.0001) because control bees exhibited higher learning than FLU-treated bees (Fig. 2C). Colony accounted for < 1% of model variance.

Figure 2.

Effect of flupyradifurone (FLU) on olfactory learning and memory (PER) in A. cerana bees treated as larvae or adults. The temporal design of the (A) learning and (B) memory trials is shown. For bees treated when they were larvae and tested as adults, we show mean PER for (C) learning (elapsed time from first trial shown in h) and (D) memory (elapsed time from the last rewarded learning trial, t5, shown). For bees treated and tested as adults (foragers), we also show mean PER for (E) learning and (F) memory. Dashed lines with stars link points that are significantly different (Tukey HSD tests, P < 0.05). Standard error bars are shown. The legend shows the FLU dose that each bee (larva or forager) received per day (see Table 1 for details).

Both doses of FLU impaired learning. In each trial that tested learning (t2–5), control bees exhibited significantly higher learning than FLU-treated bees (Tukey HSD test, P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in learning, per trial, between bees that were fed the lower or higher FLU doses (Tukey HSD test, P > 0.05, Fig. 2C).

Flupyradifurone treated bees had reduced memory

FLU treated bees were able to show greater average PER responses when their memories were tested (Fig. 2D) as compared to their PER responses during the learning trials (Fig. 2C). However, FLU resulted in lower memory scores as compared to the control (significant dose effect: F 2,883 = 4.99, P = 0.007, Fig. 2D). There was a significant overall effect of trial (F 2,894 = 17.93, P < 0.0001) because t6 showed lower average PER responses than t7 or t8 (Tukey HSD test, P < 0.05). Both lower and higher dose treated bees exhibited lower memory in t7 than control bees (Tukey HSD test, P < 0.05). There was no significant interaction of trial*dose (F 4,894 = 0.94, P = 0.44). Colony accounted for < 1% of model variance.

Adult exposure experiment

Flupyradifurone reduced adult survival

We captured foragers and fed them treatments over 3 d. Over 3 d of chronic exposure, 100% of control foragers survived. However, only 80% of foragers fed the lower dose of 0.066 µg FLU/bee/day survived as compared to controls (Fisher’s Exact test, P = 0.001DS). Foragers fed the higher dose of 0.66 µg FLU/bee/day had higher mortality: only 50% survived as compared to controls (Fisher’s Exact test, P < 0.0001DS). Thus, 0.066 and 0.66 µg FLU/bee/day respectively reduced survival by −20% and −50% after three days of exposure (Fig. 1B).

Flupyradifurone reduced learning

Bees treated as adults also showed learning (significant trial effect: F 4,1788 = 109.38, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2E). For each treatment, bees exhibited learning when the 1st and 5th trials were compared (Tukey HSD test t1 vs. t5, P < 0.05). However, control bees (0 µg FLU) showed learning after only a single rewarded trial (Tukey HSD test t1 vs. t2, t3, t4, and t5, P < 0.05). Lower dose (0.066 µg/bee/day) and higher dose (0.66 µg/bee/day) bees showed learning only after two rewarded trials (Tukey HSD test t1 vs. t3, t4, and t5, P < 0.05). Thus, there was a significant interaction of trial*dose (F 8,1788 = 10.81, P < 0.0001) because control bees exhibited greater learning than FLU-treated bees (Fig. 2E). Colony accounted for <1% of model variance.

Both FLU doses impaired learning. In each trial that tested learning (t2–5), control bees exhibited significantly higher learning than FLU-treated bees (Tukey HSD test, P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in learning, per trial, between bees that were fed the lower or higher FLU doses (Tukey HSD test, P > 0.05, Fig. 2C). Both 0.2 and 2 µg FLU/bee/day were approximately equally detrimental.

Flupyradifurone treated bees had reduced memory

Bees fed with FLU showed greater average PER responses when their memories were tested (Fig. 2F) as compared to their PER responses during the learning trials (Fig. 2E). However, FLU resulted in lower memory as compared to the control (significant dose effect: F 2,903 = 5.20, P = 0.006, Fig. 2F). There was a significant overall effect of trial (F 2,894 = 5.19, P = 0.006) because each successive trial showed higher average PER responses (Tukey HSD test, P < 0.05). Both lower- and higher-dose treated bees exhibited lower memory over all trials than controls (Tukey HSD test, P < 0.05). There was no significant interaction of trial*dose (F 4,894 = 0.94, P = 0.44). Colony accounted for <1% of model variance.

Discussion

Flupyradifurone (FLU) is thought to have a relatively low impact upon honey bees24 and has now been approved for use in multiple countries21–23 with a wide variety of crops19. However, it’s effects upon bee learning and memory were unknown. We show that sublethal levels of flupyradifurone (FLU) at field-realistic daily doses and concentrations (Table 1) impaired olfactory learning in A. cerana workers exposed as larvae or as adult foragers. All lower daily doses were field realistic, based upon data collected from foragers (Table 1). The lower dose fed to the larvae (0.033 µg/bee/day) did not alter survival to cell sealing or to adult emergence. However, the lower dose fed to adults (0.066 µg/bee/day), in a separate experiment, significantly reduced survival by 20%. In bees treated as larvae, lower and higher doses of FLU decreased olfactory learning acquisition upon adulthood, on average, by 74% and 82%, respectively (PER at t5). In bees treated as adults, lower and higher doses of FLU decreased olfactory learning, on average, by 48% and 65%, respectively (at t5). FLU-treated bees were able to show somewhat elevated PER responses when their memories were tested and thus the memory impairments, in comparisons with controls, likely arose from reduced learning, not from an impairment of memory alone. However, in bees treated as larvae, lower and higher doses resulted in average memory reductions of 48% and 41%, respectively (t7). In bees treated as adults, lower and higher doses led to average memory reductions of 19% and 22%, respectively (t7). FLU was thus 1.3 to 2.5-fold more harmful to the olfactory learning and memory of bees exposed as larvae as compared to foragers exposed as adults. Further research should therefore be conducted on the effects of FLU, expanding beyond its basic effects on bee survival and colony strength to consider its impact on bee cognition and foraging.

Field realistic doses and concentrations

Currently available field-realistic data on FLU, a relatively new systemic insecticide, are based upon the exposure of adult foragers, which is reasonable given that foragers may be exposed to FLU as they collect nectar and pollen. The doses that larvae might be exposed to per day are unknown, but are likely a fraction of doses consumed by adults. A worst-case scenario, high field-realistic dose (based upon A. mellifera collecting nectar from FLU-treated apple blossoms) is 0.44 µg/bee/day24. Our lower-dose treatments consisted of 0.033 and 0.066 µg/bee/day given to larvae and adults, respectively, and were therefore only 7.5% and 15% of this high field-realistic dose. Yet both of our low doses resulted in significant learning and memory impairments (Fig. 2). Interestingly, increasing these doses by an order of magnitude to 0.33 and 0.66 µg/bee/day did not result in significantly more impairment. Yang et al.37 also studied the effects of a nAChR agonist on honey bee learning and reported similar results. They tested olfactory learning of A. mellifera exposed to imidacloprid as larvae and tested as adults: both 0.04 ng and 0.4 ng reduced olfactory learning by roughly the same degree37. Tan et al.43 similarly studied the effects of imidacloprid on the learning of A. cerana adults exposed as adults and found that both doses (0.1 ng and 1 ng) similarly reduced learning and memory as compared with controls.

Pesticide exposure durations47 and concentrations are important, particularly in experiments in which bees are fed ad libitum because bees are being exposed, not to a pre-specified dose, but to a concentration of pesticide that they could gather over multiple days of nectar foraging. Exposure duration is crucial because pesticides can take time in accumulate in an animal’s body47. After a single foliar application, FLU residues ≥1.6 ppm have been detected for 3 d in citrus flowers and (after two foliar applications) at ≥3.5 ppm for 3 d in blueberry flowers, up to 110 ppm within 5 d for apple flowers, and 3.5–27 ppm for ≥7 d in apple, melon, and citrus flowers (MRID 4884451624). Longer exposure periods are possible. Colonies that have foraged in winter oil seed rape, FLU has been detected for up to five months in the honey and nectar stored in bee combs and for more than two weeks in nectar collected by foragers24. Shorter-term exposure is part of long-term exposure to pesticides and is also realistic since bees may not always forage for the entire period of a crop bloom or may not survive, following pesticide exposure, for longer periods. Moreover, lab studies can overestimate pesticide exposure duration48. We therefore chose a shorter exposure duration of 3 d for adults, a duration that was already sufficient to elicit a significant effect: 20% mortality at our lowest dose. Our larval exposure duration was based upon the biology of A. ceranae, whose eggs hatch into larvae and are progressively fed by nurses until their cells are sealed on the 7th day after hatching49. We therefore exposed larvae to FLU for 6 d. These conditions also matched a prior study, enabling us to make comparisons with a prior study on the effects of another nAChRs agonist upon A. cerana olfactory learning43.

In terms of FLU concentration, 4.1–4.3 ppm is the worst-case, high end of exposure from nectar consumption, based upon the analysis of forager honey stomach contents24. Because we focused on providing specific doses per bee (Table 1), we could only feed larvae a limited volume of sucrose to avoid excessively diluting the nutrients provided in their larval food. We therefore used a higher than field-realistic concentration of FLU (the lower dose corresponded to 14.6 ppm). However, for adult foragers, the lower dose was given at a concentration of 1.46 ppm, which is 35% of the higher field-realistic concentration (Table 1). For larvae, FLU was provided in their brood food, whereas FLU was fed directly to adult mouthparts. It is therefore possible that larvae consumed a smaller amount of FLU than was provided. However, if this occurred, it would demonstrate that FLU fed to larvae has an impact at even lower doses than the ones we tested.

We applied FLU over time and thus the rate at which bee metabolize FLU is also relevant. The metabolism of imidacloprid by bumble bees may provide guidance50, if these compounds are similarly degraded. Unfortunately, the details of how honey bees metabolize FLU are not yet known, although an insect cytochrome P450 (CYP6CM1) that confers resistance to neonicotinoids is not able to metabolize FLU19. Further studies on how insects degrade and metabolize FLU are needed.

Effects on larvae vs. adults

In Apis mellifera, olfactory learning ability increases with worker age51. We trained bees treated as larvae at 7 d of adult age and foragers at foraging age (approximately 20–22 d)49. However, our observed learning differences likely did not arise because of these age differences. In fact, control larval-treated bees (50% PER t5) showed somewhat higher learning than control adult-treated bees (40% PER t5, Fig. 2). Tan et al.43 found a similar level of learning in control bees treated as larvae (32% PER t5), but greater learning in control bees treated as adults (72% PER t5). Memory showed similar trends in our study and in Tan et al.43. Multiple factors, including genotype52 and seasonality53, influence honey bee PER learning. Our differences in control bee learning may therefore have arisen because we used different colonies and studied our bees over a different range of months than Tan et al.43.

We designed our experiments to feed larvae and adults the same total amounts of FLU over multiple days of exposure. Per day, larvae were fed half the dose given to adults because prior research suggested that larval honey bees are more sensitive to pesticides than adults37,43. However, despite receiving a smaller daily dose (and the same total dose per treatment), larvae showed more severe memory impairment (Fig. 2). These results suggest that larvae are more susceptible to FLU than adults. Likewise, Tan et al.43 showed that imidacloprid, another nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, had a stronger effect when consumed by larvae as compared to adult A. cerana. These effects extend to other species. Apis mellifera larvae fed quite low doses of imidacloprid had significantly impaired olfactory learning37, comparable to impairments that required much higher doses fed to adults46. Our results suggest that we should continue to explore effects of pesticide exposure during bee development.

Future directions

A recent study reported that A. cerana colonies reared in agricultural areas with intensive use of multiple pesticides had an impaired ability to detect odors54. Our experiments suggest that FLU impaired olfactory learning, not olfaction per se, because adults fed FLU were able to recover, to some degree, memory when tested with the rewarded odor (Fig. 2E,F). However, further studies are required to determine if olfaction is also impaired. Determining the potential colony-level effects of FLU on A. cerana are also important, given that A. cerana may be more susceptible than A. mellifera to pesticides that act on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors27,28. Our results suggest that such studies would be worthwhile, particularly if they consider the potential effects of larval exposure and how individual cognitive impairments may manifest at a colony level.

Methods

We conducted two experiments and used three different colonies per experiment, for a total of six A. cerana cerana colonies at Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China from September 2015 to March of 2016. To facilitate comparisons with a prior study in A. cerana, both experiments are closely based upon Tan et al.43, which tested the effect of the neonicotinoid pesticide, imidacloprid, chronically fed to larvae or adults upon olfactory learning.

Flupyradifurone doses and concentrations

Glaberman and White24 summarize the typical FLU concentrations and doses that bees encounter when foraging on pesticide-treated crops. The LD50 of FLU (the dose at which half of exposed bees die over a specified time period) is 1.2 µg/bee for pure FLU and 3.4 µg/bee for the seed treatment formulation24. Some of the highest concentrations (0.44 µg/bee/day) are reported in apples given a foliar spray24. Field-realistic high FLU concentrations of 4.3 ppm and 4.1 ppm were found in the honey stomachs of foragers collecting nectar from oilseed rape treated with FLU at manufacturer-recommended application levels MRID 48844516 and MRID 48844517 in 24.

In our experiments, we chronically fed bees fixed doses of analytical grade flupyradifurone (Sigma Aldrich, CAS# 951659–40–8, catalog# 37050-100MG) to ensure that each bee received the same dose (Table 1). Each week, we prepared fresh solutions with double-distilled water from a concentrated stock solution. All solutions were stored at 4° C and wrapped in aluminum foil to prevent potential light degradation.

Our goal was to achieve the following total FLU doses administered over multiple days: 0 µg/bee (control), 0.2 µg/bee (lower), and 2.0 µg/bee (higher) in 1 M sucrose solution. We used 1 M sucrose solution (30% sucrose w/w) to provide a better comparison with a prior A. cerana study43 and because honey bees typically collect floral nectar in the range of 19–60% (w/v)55,56. Larvae were fed over 6 d and therefore received 0, 0.033, or 0.33 µg FLU/bee/day. Adults were fed over 3 d and received 0, 0.066, or 0.66 µg FLU/bee day. Larvae were fed a lower range of doses because prior research showed that honey bee larvae may be more sensitive to nicotinic acetylcholine agonists than adult bees37. Bees were fed FLU at concentrations of 0, 1.46, 14.6, or 146.4 ppm, depending upon the experiment (Table 1).

Effects of larval exposure to FLU upon subsequent adult learning and memory

To determine the effects of FLU fed to larvae, we used three different colonies. We took 50 bees per colony per treatment (150 bees/treatment). We used three treatments and tested a total of 450 bees.

To treat the larvae, we removed a brood comb (one comb per treatment) from each colony, overlaid it with a clear acetate sheet, and marked where the queen had laid eggs. We then returned this comb to the colony. After the eggs had hatched (3 days later), we removed the comb and gently pipetted 2 µl of treatment solution into the larval food of each cell (which now contained a 1-day old larva). Each larva was fed a 1 M sucrose solution containing 0, 0.033, or 0.33 µg FLU/bee/day for 6 days (0 ppb, 14.6 ppb, or, 146.4 ppb, Table 1). This resulted in total doses of 0, 0.2, or 2 µg/bee over the 6 days of chronic exposure. We chose 2 µl because preliminary trials showed that larvae readily consumed this entire volume. We simultaneously tested all three treatments with each colony.

In each colony, for each treatment dose, we fed approximately 250 larvae to obtain a sufficiently large sample size to examine the mortality effects of FLU (total of 2334 larvae treated). However, we only tested PER learning in a randomly selected subset of these bees.

On the 7th day, when A. cerana cells are normally sealed43, we removed control and pesticide-treated combs, counted how many of the treated cells were sealed, and removed all of the larvae and pre-pupae that were not in any treatment group to ensure that only treated bees emerged. Each comb was placed in a different box in the same incubator (35 °C at 60% humidity) for about 10 days until adult bees emerged. We counted the number of bees that emerged from each treatment.

These newly emerged workers were maintained in the incubator with the food naturally stored in their respective combs until they were 7 days of adult age. A random subset of bees was then removed, each placed in an individual vial, cold anesthetized on ice for 1–2 min until their movements substantially diminished, and then placed in a modified plastic centrifuge tubes with just the heads exposed for PER testing method of 44.

We then placed each bee in the olfactory conditioning apparatus and familiarized it with the primary, unscented airflow (50 mL/s) for 15 s43,57. Bees were exposed to the olfactory conditioned stimulus (CS) via a secondary air flow (2.5 mL/s) through a Pasteur pipette into which we inserted a clear filter paper strip with 10 µL of pure hexanal (Sigma-Aldrich, 98% pure, CAS# 66-25-1, Lot# MKBG1555V).

We used a modified olfactory conditioning protocol43 based upon Bitterman et al.58. We presented the CS only for 3 s (scoring proboscis extension, PER, during this time), and then presented the unconditioned stimulus (US = 1 M pure sucrose solution containing no pesticide) for 3 s. In the rewarded learning trials, the CS continued such that CS and US overlapped for 3 s (Fig. 2A). To assess learning, we conducted five rewarded learning trials (t1–5), each with a 10 min intertrial interval. To assess memory, we subsequently tested responses to 3 s of odor alone with no sucrose reward (Fig. 2B) at intervals of 1 h (t6), 2 h (t7), and 11 h (t8) after the last rewarded learning trial (t5)43. Less than 5% of bees had a spontaneous PER response to odor only in t1 (before learning could have occurred) or showed no PER after antennal stimulation with 1.0 M sucrose. We excluded these bees from our analyses (standard protocol of 58.)

Effects of adult exposure to FLU upon adult learning and memory

For this experiment, we used a different set of three colonies and only fed FLU to adult foragers, not larvae. As in the larval experiment, we also tested 50 bees per colony per treatment (150 bees/treatment, a total of 450 bees for the three treatments). We captured likely foragers by slowly and carefully approaching a colony to avoid alarming guard bees and using a clean plastic bottle to capture foragers as they flew away from the nest entrance43.

We cold-anesthetized these foragers and restrained them as described above. Restrained adult foragers were fed 20 µl of sucrose solution containing one of the three treatments, all in 1 M sucrose. Each adult bee was fed twice a day (each 12 h) over 3 d to achieve 0, 0.06, or 0.66 µg FLU/bee/day and total doses of 0, 0.2, and 2.0 µg FLU/bee after 3 d of exposure (Table 1). During these 3 d, they were incubated at 35 °C at 60% humidity. Bees were also incubated under the same conditions for 1 h after their last feeding to allow pesticide absorption. We ran all three treatment groups in parallel during each trial. As in the larval experiment, < 5% of these bees were excluded58 because they showed spontaneous PER to odor before conditioning or failed to show PER upon antennal stimulation.

Statistics

We used JMP v12 Pro statistical software. For each experiment, we separately analyzed learning acquisition (t1–5) and memory (t6–8, Fig. 2). We used repeated-measures, REML algorithm Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to analyze the fixed effects of treatment (nominal variable) and trial (ordinal variable). Colony and bee identity were included in each model as random effects. To explore the detailed effects of treatment and trial, we used Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) tests, which correct for potential Type I statistical error59. To determine if the pesticide-treated bees had lower rates of survival than control bees, we used Fisher’s Exact 2-tailed tests60 calculated using GraphPad online software (https://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/contingency1.cfm). For these tests, we applied the Dunn-Sidak correction59 because each pesticide-treated group was compared with the same control group (k = 2). We designated tests that passed the Dunn-Sidak correction as DS.

Data availability

All data are available in the supplemental data spreadsheet.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Simone Tosi, Heather Bell, and the anonymous reviewers whose comments have improved this paper. Our work was supported by the Key Laboratory of Tropical Forest Ecology, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, and the CAS (2017XTBGT01) of Chinese Academy of Science, China National Research Fund (31770420) to Ken Tan. James C. Nieh was partially supported by an AVAAZ grant. AVAAZ declares that it has no influence or control over the research design, methodology, analysis, or findings of this research.

Author Contributions

K.T. and J.C.N. conceived of and designed the experiments. C.W., S.D. and X.L. performed the experiments. K.T. and J.C.N. analyzed the data. K.T. and J.C.N. contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. K.T. and J.C.N. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-18060-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ken Tan, Email: kentan@xtbg.ac.cn.

James C. Nieh, Email: jnieh@ucsd.edu

References

- 1.Desneux N, Decourtye A, Delpuech J-M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Ann. Rev. Ent. 2007;52:81–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez-Bayo F. The trouble with neonicotinoids. Science. 2014;346:806–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1259159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein AM, et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2007;274:303–313. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez-Bayo F, Belzunces L, Bonmatin J-M. Lethal and sublethal effects, and incomplete clearance of ingested imidacloprid in honey bees (Apis mellifera) Ecotox. 2017;26:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10646-017-1845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goulson D. An overview of the environmental risks posed by neonicotinoid insecticides. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013;50:977–987. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundin O, Rundlöf M, Smith HG, Fries I, Bommarco R. Neonicotinoid insecticides and their impacts on bees: A systematic review of research approaches and identification of knowledge gaps. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0136928–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Bayo F, et al. Are bee diseases linked to pesticides? — A brief review. Environment International. 2016;89–90:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aizen MA, Harder LD. The global stock of domesticated honey bees is growing slower than agricultural demand for pollination. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:915–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng YS, Nasr ME, Locke SJ. Geographical races of Apis cerana Fabricius in China and their distribution. Review of recent Chinese publications and a preliminary statistical analysis. Apidologie. 1989;20:9–20. doi: 10.1051/apido:19890102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang YG. Harm of introducing the western honeybee Apis mellifera L. to the Chinese honeybee Apis cerana F. and its ecological impact. Acta Entomol. Sinica. 2005;48:401–406. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verma, L. R. & Partap, U. The Asian hive bee, Apis cerana, as a pollinator in vegetable seed production. (International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) (1993).

- 12.Corlett RT. Pollination in a degraded tropical landscape: a Hong Kong case study. J. Trop. Ecol. 2001;17:155–161. doi: 10.1017/S0266467401001109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng YS, Fang Y, Xu S, Ge L. The resistance mechanism of the Asian honey bee, Apis cerana Fabr., to an ectoparasitic mite, Varroa jacobsoni Oudemans. J. Invert. Path. 1987;49:54–60. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(87)90125-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Z, et al. Go east for better honey bee health: Apis cerana is faster at hygienic behavior than A. mellifera. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0162647–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis JD, Munn PA. The worldwide health status of honey bees. Bee World. 2005;86:88–101. doi: 10.1080/0005772X.2005.11417323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, et al. The prevalence of parasites and pathogens in Asian honeybees Apis cerana in China. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e47955–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He X, Liu XY. An analysis of the causes of the decline in the population of Apis cerana in China. Apiculture of China. 2011;62:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanley J, Sah K, Jain SK, Bhatt JC, Sushil SN. Evaluation of pesticide toxicity at their field recommended doses to honeybees, Apis cerana and A. mellifera through laboratory, semi-field and field studies. Chemosphere. 2015;119:668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nauen, R. et al. Flupyradifurone: a brief profile of a new butenolide insecticide. Pest. Manag. Sci. n/a–n/a, 10.1002/ps.3932 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Jeschke P, Nauen R, Beck ME. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists: a milestone for modern crop protection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:9464–9485. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.USA EPA. Notice of pesticide registration for flupyradifurone, EPA reg. no. 264-1143. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs, Environmental Fate and Effects Division EFED, Environmental Risk Branch IV 1–6 (2015).

- 22.European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Setting of new maximum residue levels for flupyradifurone in strawberries, blackberries and raspberries. EFSA Journal14, 4423 (2016).

- 23.AgroNews. Bayer registers first honeybee-low-toxic insecticide Flupyradifurone in China. AgroPages.com (2016). Available at: https://www.agra-net.com/agra/agrow/approvals-launches/china-approves-bayers-flupyradifurone-533811.htm. (Accessed: 25 May 2017).

- 24.Glaberman, S. & White, K. Environmental fate and ecological risk assessment for foliar, soil drench, and seed treatment uses of the new insecticide flupyradifurone (byi 02960). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs, Environmental Fate and Effects Division EFED, Environmental Risk Branch IV 187 (2014).

- 25.Campbell JW, Cabrera AR, Stanley-Stahr C, Ellis JD. An evaluation of the honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) safety profile of a new systemic insecticide, flupyradifurone, under field conditions in Florida. Ecotox. 2016;109:1967–1972. doi: 10.1093/jee/tow186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arena M, Sgolastra F. A meta-analysis comparing the sensitivity of bees to pesticides. Ecotox. 2014;23:324–334. doi: 10.1007/s10646-014-1190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C, Jeong S, Jung C, Burgett M. Acute oral toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides to four species of honey bee, Apis florea, A. cerana, A. mellifera, and A. dorsata. Journal of Apiculture. 2016;31:51. doi: 10.17519/apiculture.2016.04.31.1.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yasuda M, Sakamoto Y, Goka K, Nagamitsu T, Taki H. Insecticide susceptibility in Asian honey bees (Apis cerana (Hymenoptera: Apidae)) and implications for wild honey bees inAsia. Ecotox. 2017;110:447–452. doi: 10.1093/jee/tox032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moffat C, et al. Neonicotinoids target distinct nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and neurons, leading to differential risks to bumblebees. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep24764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson RM. Honey bee toxicology. Ann. Rev. Ent. 2015;60:415–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decourtye A, Henry M, Desneux N. Environment: overhaul pesticide testing on bees. Nature. 2013;497:188–188. doi: 10.1038/497188a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giurfa M, Sandoz JC. Invertebrate learning and memory: fifty years of olfactory conditioning of the proboscis extension response in honeybees. Learn. Mem. 2012;19:54–66. doi: 10.1101/lm.024711.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanley DA, Smith KE, Raine NE. Bumblebee learning and memory is impaired by chronic exposure to a neonicotinoid pesticide. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:128–10. doi: 10.1038/srep16508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piiroinen S, Botías C, Nicholls E, Goulson D. No effect of low-level chronic neonicotinoid exposure on bumblebee learning and fecundity. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1808–18. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williamson SM, Baker DD, Wright GA. Acute exposure to a sublethal dose of imidacloprid and coumaphos enhances olfactory learning and memory in the honeybee Apis mellifera. Invert. Neurosci. 2012;13:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s10158-012-0144-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Decourtye A, Devillers J, Cluzeau S, Charreton M, Pham-Delègue M-H. Effects of imidacloprid and deltamethrin on associative learning in honeybees under semi-field and laboratory conditions. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2004;57:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang E-C, Chang H-C, Wu W-Y, Chen Y-W. Impaired olfactory associative behavior of honeybee workers due to contamination of imidacloprid in the larval stage. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e49472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williamson SM, Willis SJ, Wright GA. Exposure to neonicotinoids influences the motor function of adult worker honeybees. Ecotox. 2014;23:1409–1418. doi: 10.1007/s10646-014-1283-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piiroinen S, Goulson D. Chronic neonicotinoid pesticide exposure and parasite stress differentially affects learning in honeybees and bumblebees. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2016;283:20160246–8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright GA, Softley S, Earnshaw H. Low doses of neonicotinoid pesticides in food rewards impair short-term olfactory memory in foraging-age honeybees. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–7. doi: 10.1038/srep15322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urlacher E, et al. Measurements of chlorpyrifos levels in forager bees and comparison with levels that disrupt honey bee odor-mediated learning under laboratory conditions. J. Chem. Ecol. 2016;42:127–138. doi: 10.1007/s10886-016-0672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han P, Niu C-Y, Lei C-L, Cui J-J, Desneux N. Use of an innovative T-tube maze assay and the proboscis extension response assay to assess sublethal effects of GM products and pesticides on learning capacity of the honey bee Apis mellifera L. Ecotox. 2010;19:1612–1619. doi: 10.1007/s10646-010-0546-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan K, et al. A neonicotinoid impairs olfactory learning in Asian honey bees (Apis cerana) exposed as larvae or as adults. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan K, Yang S, Wang Z. Effect of flumethrin on survival and olfactory learning in honeybees. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e66295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu JY, Anelli CM, Sheppard WS. Sub-lethal effects of pesticide residues in brood comb on worker honey bee (Apis mellifera) development and longevity. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e14720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson SM, Wright GA. Exposure to multiple cholinergic pesticides impairs olfactory learning and memory in honeybees. J._ Exp. Biol. 2013;216:1799–1807. doi: 10.1242/jeb.083931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rondeau G, et al. Delayed and time-cumulative toxicity of imidacloprid in bees, ants and termites. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep05566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carreck NL, Ratnieks FLW. The dose makes the poison: have ‘field realistic’ rates of exposure of bees to neonicotinoid insecticides been overestimated in laboratory studies? J. Apic. Res. 2015;53:607–614. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.53.5.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruttner, F. Biogeography and taxonomy of honeybees. (Springer Verlag, (1988).

- 50.Cresswell JE, Robert F-XL, Florance H, Smirnoff N. Clearance of ingested neonicotinoid pesticide (imidacloprid) in honey bees (Apis mellifera) and bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) Pest. Manag. Sci. 2014;70:332–337. doi: 10.1002/ps.3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ichikawa N, Sasaki M. Importance of social stimuli for the development of learning capability in honeybees. Applied Entomology and Zoology. 2003;38:203–209. doi: 10.1303/aez.2003.203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheiner R, Page RE, Erber J. Responsiveness to sucrose affects tactile and olfactory learning in preforaging honey bees of two genetic strains. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;120:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scheiner R, Barnert M, Erber J. Variation in water and sucrose responsiveness during the foraging season affects proboscis extension learning in honey bees. Apidologie. 2003;34:67–72. doi: 10.1051/apido:2002050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chakrabarti P, et al. Field populations of native Indian honey bees from pesticide intensive agricultural landscape show signs of impaired olfaction. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker HG. Sugar concentrations in nectars from hummingbird flowers. Biotropica. 1975;7:37–41. doi: 10.2307/2989798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roubik DW, Yanega D, Aluja AM, Buchmann SL, Inouye DW. On optimal nectar foraging by some tropical bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Apidologie. 1995;26:197–211. doi: 10.1051/apido:19950303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Decourtye A, Lacassie E, Pham-Delègue MH. Learning performances of honeybees (Apis mellifera L) are differentially affected by imidacloprid according to the season. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2003;59:269–278. doi: 10.1002/ps.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bitterman ME, Menzel R, Fietz A, Schäfer S. Classical conditioning of proboscis extension in honeybees (Apis mellifera) J. Comp. Psychol. 1983;97:107–119. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.97.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zar, J. H. Biostatistical analysis. (Prentice-Hall, 1984).

- 60.Upton GJG. Fisher’s Exact test. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 1992;155:395–402. doi: 10.2307/2982890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the supplemental data spreadsheet.